Astrology: Difference between revisions

Robertcurrey (talk | contribs) m sp corrected Rawlins not Rawlings |

Itsmejudith (talk | contribs) →Carlson's experiment: keep Eysenck's critique in for the time being, Eysenck notable though here out of his field, rm studies in fringe journals |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

{{cite web|last=Maddox|first=Sir John|title=John Maddox, editor of the science journal Nature, commenting on Carlson's test|year=1995|accessdate=2011-08-02|url=http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:fqwVx-Bt9BMJ:www.randi.org/encyclopedia/astrology.html+maddox+perfectly+convincing+and+lasting+demonstration&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&source=www.google.com}}''"... a perfectly convincing and lasting demonstration."''</ref> of these is [[Shawn Carlson|Shawn Carlson's]] double-blind chart matching tests in which he challenged 28 astrologers to match over 100 natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the [[California Psychological Inventory]] (CPI) test. When Carlson's study was published in [[Nature (journal)|Nature]] in 1985, his conclusion was that natal astrology as practiced by reputable astrologers was no better than chance.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Carlson|first=Shawn|title=A double-blind test of astrology|journal=Nature|year=1985|volume=318|pages=419–425|url=http://muller.lbl.gov/papers/Astrology-Carlson.pdf|doi=10.1038/318419a0|issue=6045|bibcode = 1985Natur.318..419C }}</ref> |

{{cite web|last=Maddox|first=Sir John|title=John Maddox, editor of the science journal Nature, commenting on Carlson's test|year=1995|accessdate=2011-08-02|url=http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:fqwVx-Bt9BMJ:www.randi.org/encyclopedia/astrology.html+maddox+perfectly+convincing+and+lasting+demonstration&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&source=www.google.com}}''"... a perfectly convincing and lasting demonstration."''</ref> of these is [[Shawn Carlson|Shawn Carlson's]] double-blind chart matching tests in which he challenged 28 astrologers to match over 100 natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the [[California Psychological Inventory]] (CPI) test. When Carlson's study was published in [[Nature (journal)|Nature]] in 1985, his conclusion was that natal astrology as practiced by reputable astrologers was no better than chance.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Carlson|first=Shawn|title=A double-blind test of astrology|journal=Nature|year=1985|volume=318|pages=419–425|url=http://muller.lbl.gov/papers/Astrology-Carlson.pdf|doi=10.1038/318419a0|issue=6045|bibcode = 1985Natur.318..419C }}</ref> |

||

The psychologist [[Hans Eysenck]] wrote a critique of this paper.<ref>[[#Reference-Eysenck-1986|Eysenck (1986)]]. Eysenck's assessment was to find: "The conclusion does not follow from the data".</ref> |

|||

<ref name="ertel-c">{{cite journal|last=Ertel|first=Suitbert|title=Appraisal of Shawn Carlson's Renowned Astrology Tests|journal=Journal of Scientific Exploration|year=2009|volume=23|issue=2|pages=125–137|url=http://www.scientificexploration.org/journal/full/jse_23_2_full.pdf#page=7}} "The design of Carlson’s study violated the demands of fairness and its mode of analysis ignored common norms |

|||

of statistics".</ref> |

|||

When the stated measurement criterion was applied, and the published data was evaluated according to the normal conventions of the [[social sciences]], the two tests performed by the participating astrologers provided marginally [[Statistical significance|significant evidence]] (astrologers' ranking test: [[P value|p]] = .054 with [[Effect size|ES]] = .15, and astrologers' rating test: p = .037 with ES = .10), despite the unfair design, of their ability to successfully match CPIs to natal charts.<ref name="ertel-c" /> Observers have called for more detailed and stringent double-blind experiments.<ref name="mcritchie">{{cite journal|last=McRitchie|first=Ken|title=Support for astrology from the Carlson double-blind experiment|journal=ISAR International Astrologer|year=2011|month=August|volume=40|issue=2|pages=33–38|url=http://www.theoryofastrology.com/carlson/carlson.htm}}</ref> |

|||

===Obstacles to research=== |

===Obstacles to research=== |

||

Revision as of 17:15, 27 September 2011

Astrology is the study of celestial bodies interpreted as affecting personality, human affairs, and natural events.[1] The primary astrological bodies are the Sun, Moon, and planets, which are analyzed by their aspects (relative positions to one another), by their placement in 'houses' (spatial divisions of the sky), and their movement through signs of the zodiac (spatial divisions of the ecliptic).

Astrology’s origins trace to the third millennium BCE. Ancient civilizations developed it as a calendrical system to predict seasonal shifts and to interpret celestial cycles as ‘signs’ of ‘divine communications’.[2] Historically it was a learned tradition, sustained in courts, cultural centers and universities, and was closely related to the studies of astronomy, alchemy, meteorology, and medicine.[3] Yet despite their closely connected histories, astrology and astronomy separated at the end of the 17th century, when astronomy redefined many of the theoretical concepts that the two disciplines had previously shared. Subsequently, astrology suffered a decline in academic and theoretical credibility. The 20th century brought renewed attention, partly through the popularizing effect of newspaper horoscopes and New Age philosophies, and through re-kindled intellectual interest in statistically testing astrology's claims.[4]

Astrologers have long debated the degree of determinism in astrology. Some believe that celestial movements control fate, others that they determine only disposition and potential. While most astrologers contend there is no direct influence from the stars (only a synchronistic correlation between the celestial and terrestrial) astrology has been criticized for not offering a clear account of its physical mechanism and failing to develop new theories in line with modern scientific principles.[5] It has thus been called a pseudoscientific subject by members of the modern scientific community.[6]

Etymology and basic definitions

Astrology, in its broadest sense, is the search for meaning in the sky,[7] the acquisition of significance being drawn from a combination of observation, correlation, philosophy, logic and lore.

The word astrology comes from the Latin astrologia,[8] deriving from the Greek noun αστρολογία, which combines ἄστρο astro, 'star / celestial body' with λογία logia, 'study of / theory / discourse (about)'.[9]

Hence astrology, in its original meaning, describes the theory of celestial significance; as distinct from astronomy, the technical counterpart which aims to establish the mathematical principles (laws) of celestial events (from the Greek:ἄστρο and νόμος nomos, 'custom / law / ordinance'). Although the two studies are historically twinned, and anciently the terms astrologos ‘astrologer’ and astronomos ‘astronomer’ were used interchangeably,[10] texts dating from the classical period show a conceptual differentiation between them, demonstrated by Ptolemy’s authoritative 2nd-century text on astronomy (Almagest) remaining entirely free of the themes presented in his astrological treatise (Tetrabiblos). (The two disciplines formally separated at the end of the 17th century when astronomy redefined many of the theoretical concepts it had previously shared with astrology.)[11]

Historically, the word star has had a loose definition, by which it can refer to planets or any luminous celestial object.[12] The notion of it signifying all heavenly bodies is evident in early Babylonian astrology where cuneiform depictions for the determinative MUL (star) present a symbol of stars alongside planetary and other stellar references to indicate deified objects which reside in the heavens.[a] The word planet (based on the Greek verb πλανάω planaō 'to wander/stray'), was introduced by the Greeks as a reference to how seven notable 'stars' were seen to 'wander' through others which remained static in their relationship to each other, with the distinction noted by the terms ἀστέρες ἀπλανεῖς asteres aplaneis ‘fixed stars’, and ἀστέρες πλανῆται asteres planetai, ‘wandering stars’.[13] Initially, texts such as Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos referred to the planets as 'the star of Saturn', 'the star of Jupiter', etc., rather than simply 'Saturn' or 'Jupiter',[14] but the names became simplified as the word planet assumed astronomical formality over time.[15]

The seven Classical planets therefore comprise the Sun and Moon along with the solar-system planets that are visible to the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. This remained the standard definition of the word 'planet' until the discovery of Uranus in 1781 created a need for revision.[16] Although the modern IAU definition of planet does not include the Sun and the Moon, astrology retains historical convention in its description of those astronomical bodies, and also generally maintains reference to Pluto as being an astrological planet.[b]

Core principles

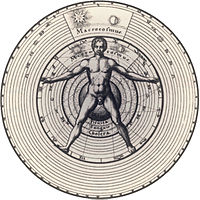

A central principle of astrology is integration within the cosmos. The individual, Earth, and its environment are viewed as a single organism, all parts of which are correlated with each other.[17] Cycles of change that are observed in the heavens are therefore reflective (not causative) of similar cycles of change observed on earth and within the individual.[18] This relationship is expressed in the Hermetic maxim "as above, so below; as below, so above", which postulates symmetry between the individual as a microcosm and the celestial environment as a macrocosm.[19] Accordingly, the natal horoscope depicts a stylized map of the universe at the time of birth, specifically focussed on the individual at its centre, with the Sun, Moon, and celestial bodies considered to be that individual’s personal planets or stars, which are uniquely relevant to that individual alone.[20]

At the heart of astrology is the metaphysical principle that mathematical relationships express qualities or ‘tones' of energy which manifest in numbers, visual angles, shapes and sounds – all connected within a pattern of proportion. Pythagoras first identified that the pitch of a musical note is in proportion to the length of the string that produces it, and that intervals between harmonious sound frequencies form simple numerical ratios.[21] In a theory known as the Harmony of the Spheres, Pythagoras proposed that the Sun, Moon and planets all emit their own unique hum based on their orbital revolution,[22] and that the quality of life on Earth reflects the tenor of celestial sounds which are physically imperceptible to the human ear.[19] Subsequently, Plato described astronomy and music as "twinned" studies of sensual recognition: astronomy for the eyes, music for the ears, and both requiring knowledge of numerical proportions.[23]

Later philosophers retained the close association between astronomy, optics, music and astrology, including Ptolemy, who wrote influential texts on all these topics.[24] Alkindi, in the 9th century, developed Ptolemy's ideas in De Aspectibus which explores many points of relevance to astrology and the use of planetary aspects.[25] In the 17th century, Kepler, also influenced by arguments in Ptolemy’s Optics and Harmonica,[26] compiled his Harmonices Mundi ('Harmony of the World'), which presented his own analysis of optical perceptions, geometrical shapes, musical consonances and planetary harmonies. Kepler regarded this text as the most important work of his career, and the fifth part, concerning the role of planetary harmony in Creation, the crown of it.[27] His premise was that, as an integral part of Universal Law, mathematical harmony is the key that binds all parts together: one theoretical proposition from his work introduced the minor planetary aspects into astrology; another introduced Kepler’s third law of planetary motion into astronomy.[28] Another core principle is exemplified by an astrological maxim used by the leader of early modern science, Francis Bacon: "The last rule (which has always been held by the wiser astrologers) is that there is no fatal necessity in the stars; but that they rather incline than compel".[29] Bacon advocated an emphasis on what he called "sane astrology" based on the study of subtle influences that "lie concealed in the depths of Physic".[30] His arguments reflect how astrology has always involved consideration of the psyche, a more recent expression of which can be found in the writings of Carl Jung and the development of modern psychological astrology.

History

Ancient world

Astrology began as a study as soon as conscious attempts were made to measure, record, and predict seasonal changes by reference to astronomical cycles.[31] Early evidence of this appears as markings on bones and cave walls, which show lunar cycles were being noted as early as 25,000 years ago; the first step towards recording the Moon’s influence upon tides and rivers, and towards organizing a communal calendar.[32] Agricultural needs were also met by increasing knowledge of constellations, whose appearances change with the seasons, allowing the rising of particular star-groups to herald annual floods or seasonal activities.[33] By the third millennium BCE, widespread civilizations had developed sophisticated awareness of celestial cycles, and are believed to have consciously oriented their temples to create alignment with the heliacal risings of the stars.[34]

There is scattered evidence to suggest that the oldest known astrological references are copies of texts made during this period. Two, from the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa (compiled in Babylon round 1700 BCE) are reported to have been made during the reign of king Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE).[35] Another, showing an early use of electional astrology, is ascribed to the reign of the Sumerian ruler Gudea of Lagash (ca. 2144-2124 BCE). This describes how the gods revealed to him in a dream the constellations that would be most favourable for the planned construction of a temple.[36] However, controversy attends the question of whether they were genuinely recorded at the time or merely ascribed to ancient rulers by posterity. The oldest undisputed evidence of the use of astrology as an integrated system of knowledge is therefore attributed to the records that emerge from the first dynasty of Mesopotamia (1950-1651 BC). This gives astrology a recognised 4,000 year history as a body of organised logic which can be seen to have been employed in the affairs of a civilised state.

Byzantine and early medieval Islamic astrology

Astrology was taken up enthusiastically by Islamic scholars following the collapse of Alexandria to the Arabs in the 7th century, and the founding of the Abbasid empire in the 8th. The second Abbasid caliph, Al Mansur (754-775) founded the city of Baghdad to act as a centre of learning, and included in its design a library-translation centre known as Bayt al-Hikma ‘Storehouse of Wisdom’, which continued to receive development from his heirs and was to provide a major impetus for Arabic-Persian translations of Hellenistic astrological texts.[37] The early translators included Mashallah, who helped to elect the time for the foundation of Baghdad,[38] and Sahl ibn Bishr (a.k.a Zael), whose texts were directly influential upon later European astrologers such as Guido Bonatti in the 13th century, and William Lilly in the 17th century.[39] Knowledge of Arabic texts started to become imported into Europe during the Latin translations of the 12th century, the effect of which was to help initiate the European Renaissance.

Other important Arabic astrologers include Albumasur and Al Khwarizmi, the Persian mathematician, astronomer and astrologer, who is considered the father of algebra and the algorithm. The Arabs greatly increased the knowledge of astronomical cycles, and many of the star names that remain in common use today, such as Aldebaran, Altair, Betelgeuse, Rigel and Vega retain the legacy of their language.

Modern era

Early in the 20th century, Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, developed sophisticated theories concerning astrology.[40] These included concepts such as archetypes, the collective unconscious[41] and with the collaboration of pioneer theoretical physicist (and Nobel laureate), Wolfgang Pauli, synchronicity.[42] Astrologers like Dane Rudhyar[43] pursued a similar path to Jung and others such as Liz Greene[44][45] and Stephen Arroyo[46] were influenced by the Jungian model leading to the development of psychological astrology.[47]

During the middle of the 20th century, Alfred Witte and, following him, Reinhold Ebertin pioneered the use of midpoints called Midpoint Astrology in horoscopic analysis.[48] A new kind of Locational Astrology began in 1957–58, when Donald Bradley, published a hand-plotted geographic astrology map. In the 1970s, American astrologer Jim Lewis developed this technique under the name of Astro*Carto*Graphy.[49] The world map displays lines where the Sun, Moon, planets and other celestial points appear to be on any of the Four Angles (Rising, Setting, MC and IC) at a given moment in time. By comparing these lines with the horoscope, an astrologer attempts to identify the potential in any location.[50]

Culture influence

Belief in astrology holds firm today in many parts of the world: in one poll, 31% of Americans expressed belief in astrology and according to another study 39% considered it scientific.[51] According to Gallup opinion polls, around 25% of adults in the UK and USA accept that astrology or the position of the stars and planets affect people’s lives, whilst other sources report the figure to be much higher.[52]

Astrology has had an influence on both language and literature. For example, influenza, from medieval Latin influentia 'influence', was so named because doctors once believed epidemics to be caused by unfavourable celestial influences.[53] The word disaster comes from the Greek δυσαστρία, disastria, derived from the negative prefix δυσ-, dis- and αστήρ, aster 'star', meaning not-starred or badly-starred.[54] The adjectives lunatic (Luna/Moon), mercurial (Mercury), venereal (Venus), martial (Mars), jovial (Jupiter/Jove), and saturnine (Saturn) are all used to describe personal qualities thought to be influenced by the astrological characteristics of predominating personal planets.

In literature many writers, such as Chaucer and Shakespeare, used astrological symbolism to add subtlety and nuance to the description of their characters' motivations.[55] More recently, Michael Ward has proposed that C.S. Lewis imbued his Chronicles of Narnia with the characteristics and symbols of the seven planets that govern the heavens in medieval astrology.[56] In 1978, notes from Margaret Mitchell’s library revealed that she had based each character from her classic prize-winning novel, Gone with Wind (1936), including the central star-crossed lovers, Scarlett (Aries) and Rhett (Leo), around an archetype of the zodiac.[57] In 2010, a detailed personal horoscope analyzed and illustrated by J.K. Rowling at the time she was writing her first Harry Potter novel, came up for sale. The auctioneer commented that Rowling “displays a detailed knowledge of Western astrology which was later to play an important part in her books".[58] Often, an understanding of astrological symbolism is needed to fully appreciate such literature.

In music the best known example of astrology's influence is in the orchestral suite The Planets by British composer Gustav Holst, the framework of which is based on the astrological tones and signatures of the planets.[59]

Research

Although astrology has not been considered a science for some time, it has been the subject of research studies by astrologers since before the 20th century.[61]

Methods

The investigation of astrology has used the empirical methods of both qualitative research and quantitative research. The most common forms of qualitative research are case study and pattern matching (cycle research), but data coding, and grounded theory have also been used. These are all methods that astrology shares with the social sciences and observers have called for a more disciplined approach in their use.[62] One area of cycle research examines correspondences between the long term revolutions of planetary alignments and recurrent historic cultural themes as researched, for example, by Richard Tarnas.[63] Another area that combines cycle research with data coding is referred to as cosmic cybernetics, a term coined by Theodor Landscheidt. This method compares the harmonic frequencies and structures of planetary positions to statistical evaluations of data, including economic indexes. This approach, which hearkens back to 17th century astronomer Johannes Kepler, has been increasingly developed through trend fitting and computer modeling.[48][64][65][66][67]

The use of statistical inference as an empirical method of quantitative research in astrology was recognized by early modern scientists and one of the first attempts at this method of experimentation was John Goad's 30-year astrological study of weather Astro-Meteorologica published in 1686. By the latter half of the 20th century, statistical methods and access to accurate birth data had improved and sophisticated research efforts on larger scales became possible. Some of these experiments attempted to definitively test whether astrological propositions and practices could be either supported or falsified.[61] Two examples stand out as the most closely scrutinized and best documented of this type of research. The first is the large scale statistical experiments that challenged astrological propositions by French psychologist and statistician Michel Gauquelin. The second is the double-blind chart interpretation experiment that challenged astrological practice by American science educator Shawn Carlson. Controversy, skepticism, and accusations have dogged both of these studies through many twists and turns.[68]

Gauquelin's research

In 1955, Michel Gauquelin published the claim that although he had failed to find evidence to support such indicators as the zodiacal signs and planetary aspects in astrology, he had found positive correlations between the diurnal positions of some of the planets and success in professions (such as doctors, scientists, athletes, actors, writers, painters, etc.) which astrology traditionally associates with those planets.[60] The immense weight of the Gauquelin claim, which in the words of American astronomer George Abell, "would lie well beyond anything that science could at present understand,"[69] was grounds for skeptics to maintain, as long as possible, "less incredible explanations" of those results.[70] The most well-known of Gauquelin's findings, which has been repeatedly tested in various studies and fought over, is based on the positions of Mars in the natal charts of successful athletes and became known as the "Mars effect".[71]

In a long series of tests and counter-tests spanning decades of discourse, Gauquelin and independent studies by other scientists verified that the Mars effect is not due to astronomical or demographic artifacts,[72] that the methodologies were free from error,[73] that studies of independently collected data demonstrated the effect,[74][75][76] that birth-time shuffle tests supported the presence of the effect,[77] that the Mars effect is not found in ordinary people,[78] and that the effect cannot be explained by data selection bias.[71][79]

The issue of selection bias, as to who was a "successful" athlete, had been a major bone of contention. As a method of “raising the hurdle” to objectively eliminate selection bias in the Mars tests, German professor Suitbert Ertel developed a stringent data ranking protocol based on citation frequencies. When the entire Gauquelin database for athletes, from the famous to the inferior (N = 4,391) was tested, this data-ranking hurdle elevated the slope of the astrological effect.[80] Other planetary effects discovered by Gauquelin also crossed this hurdle.[70] However, no challenge of these planetary effects has ever successfully passed this data-ranking criterion but instead it has been ignored in subsequent skeptical research without any reason given.[81] Ertel and others have since found the eminence effect present in every data set collected by the skeptical groups.[82][83]

Carlson's experiment

A different approach to testing astrology quantitatively uses blind experiment. The most renowned[84] of these is Shawn Carlson's double-blind chart matching tests in which he challenged 28 astrologers to match over 100 natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the California Psychological Inventory (CPI) test. When Carlson's study was published in Nature in 1985, his conclusion was that natal astrology as practiced by reputable astrologers was no better than chance.[85]

The psychologist Hans Eysenck wrote a critique of this paper.[86]

Obstacles to research

Astrologers have argued that there are significant obstacles in carrying out scientific research into astrology today, including lack of funding,[87][88] insufficient background in statistics, limited experience within the scientific community on the part of proponents, and insufficient expertise and exposure to astrology by opposing researchers.[87][88][89] Some astrologers have argued that few practitioners today have the time or even care to pursue scientific testing of astrology because they feel that working with clients on a daily basis provides personal validation for their clients.[88][90]

Another argument made by astrologers is that most studies of astrology do not reflect the nature of astrological practice.[91][92] Some astrology proponents argue that the prevailing attitudes or motives of many opponents of astrology introduce conscious or unconscious bias in the formulation of hypotheses to be tested, the conduct of the tests, or the reporting of results.[89][93][94][95]

Mechanisms

In 1975, amid increasing popular interest in astrology, a widely publicized article, "Objections to Astrology," published in The Humanist in the form of a manifesto signed by 186 scientists, sparked a scientific controversy. In particular, "Objections to Astrology" focused on the question of astrological mechanisms with the following words:

We can see how infinitesimally small are the gravitational and other effects produced by the distant planets and the far more distant stars. It is simply a mistake to imagine that the forces exerted by stars and planets at the moment of birth can in any way shape our futures.

Astronomer Carl Sagan, host of the award-winning TV series Cosmos, said that he found himself unable sign the "Objections" statement, not because he thought that astrology was valid, but because he found the statement's tone authoritarian, and because objections on the grounds of an unavailable mechanism can be mistaken. "No mechanism was known," Sagan wrote, "for continental drift (now subsumed in plate tectonics) when it was proposed by Alfred Wegener... The notion was roundly dismissed by all the great geophysicists, who were certain that continents were fixed." Sagan stated that he would instead have been willing to sign a statement describing and refuting the principal tenets of astrological belief, which he believed would have been more persuasive and would have produced less controversy.[97][98]

Few astrologers believe that astrology can be explained by any direct causal mechanisms between planets and people. Researchers have posited acausal, purely correlational, relationships between astrological observations and events. For example, the theory of synchronicity proposed by Carl Jung, which draws from the Hermetic principle ("as above, so below"), postulates meaningful significance in unrelated events that occur simultaneously.[99][100] Some astrologers have posited a basis in divination.[101] Others have argued that empirical correlations stand on their own, and do not need the support of any theory or mechanism.[89] A few researchers, such as astronomer Percy Seymour, have sought to describe a mechanism[clarification needed] that could potentially explain astrology.[102][103]

Criticisms

Scientific criticism

Since the late 17th century when astronomy and astrology became separate disciplines, astrology has been increasingly criticized by scientists. For example, Christiaan Huygens wrote in his Cosmotheoros: "And as for the Judicial Astrology, that pretends to foretel what is to come, it is such a ridiculous, and oftentimes mischievous Folly, that I do not think it fit to be so much as named."[104]

Contemporary scientists, such as Richard Dawkins, regard astrology as unscientific,[105] and those such as Andrew Fraknoi of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific have labeled it a pseudoscience.[106] In a lecture in 2001, Stephen Hawking stated "The reason most scientists don't believe in astrology is because it is not consistent with our theories that have been tested by experiment."[107]

Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson asserted that "astrology was discredited 600 years ago with the birth of modern science. 'To teach it as though you are contributing to the fundamental knowledge of an informed electorate is astonishing in this, the 21st century'. Education should be about knowing how to think, 'And part of knowing how to think is knowing how the laws of nature shape the world around us. Without that knowledge, without that capacity to think, you can easily become a victim of people who seek to take advantage of you'". The founder of the school, to which Tyson's criticism was directed responded "It's quite obvious that he hasn't studied the subject."[108]

The criticisms that have been raised against astrology by modern scientists are that it is conjectural and supplies no hypotheses, proves difficult to falsify, and resolves to describe natural events in terms of scientifically untestable supernatural causes.[109][failed verification] It has also been suggested that much of the continued faith in astrology could be psychologically explained as a matter of cognitive bias.[110]

Skeptics have claimed that the practice of western astrologers allows them to avoid making verifiable predictions, and gives them the ability to attach significance to arbitrary and unrelated events, in a way that suits their purpose,[111] although science also provides methodologies to separate verifiable significance from arbitrary predictions in research experiments, as demonstrated by Gauquelin's research and Carlson's experiment.

Theological criticism

Some of the practices of astrology were refuted on theological grounds by medieval Muslim astronomers such as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) and Avicenna. Their criticisms argued that the methods of astrologers conflicted with orthodox religious views of Islamic scholars through the suggestion that the Will of God can be known and predicted in advance.[112] Such refutations mainly concerned "judicial branches" (such as Horary astrology), rather than the more "natural branches" such as Medical and Meteorological astrology, these being seen as part of the natural sciences of the time.

For example, Avicenna’s 'Refutation against astrology' Resāla fī ebṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm, argues against the practice of astrology while supporting the principle of planets acting as the agents of divine causation which express God's absolute power over creation. Avicenna considered that the movement of the planets influenced life on earth in a deterministic way, but argued against the capability of determining the exact influence of the stars.[113] In essence, Avicenna did not refute the essential dogma of astrology, but denied our ability to understand it to the extent that precise and fatalistic predictions could be made from it.[114]

Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya (1292–1350), in his Miftah Dar al-SaCadah, also used physical arguments in astronomy to question the practice of judicial astrology.[115] He recognized that the stars are much larger than the planets, and argued:[116]

And if you astrologers answer that it is precisely because of this distance and smallness that their influences are negligible, then why is it that you claim a great influence for the smallest heavenly body, Mercury? Why is it that you have given an influence to al-Ra's and al-Dhanab, which are two imaginary points [ascending and descending nodes]?

Other cultural systems of astrology

Although most cultural systems of astrology share common roots in ancient philosophies that influenced each other, many have unique methodologies which differ from those developed in the west. The two most significant of these are Hindu astrology (a.k.a 'Indian astrology', often referred to as Vedic astrology in modern times) and Chinese astrology. Both of these systems have yielded great influence upon the world's cultural history. Others include:

- Sri Lankan

- Tibetan astrology which is largely based upon Vedic Astrology with some modification according to Buddhist teachings.

Hindu

Hindu astrology uses a different zodiac than Western astrology and is a branch of Vedic science.[117][118] In India, there is a long-established widespread belief in astrology, and it is commonly used for daily life, foremost with regard to marriages, and secondarily with regard to career and electional and karmic astrology.[119][120] In the 1960s, H.R. Seshadri Iyer, introduced a system including the concepts of yogi and avayogi. It generated interest with research oriented astrologers in the West. From the early 1990s, Western Vedic astrologer and author V.K. Choudhry created and developed the Systems' Approach for Interpreting Horoscopes, a simplified system of Jyotish (predictive astrology)[121] The system, also known as "SA", helps those who are trying to learn Jyotisha. The late K.S. Krishnamurti developed the Krishnamurti Paddhati system based on the analysis of the stars (nakshatras), by sub-dividing the stars in the ratio of the dasha of the concerned planets. The system is also known as "KP" and "sub theory". In 2001, Indian scientists and politicians debated and critiqued a proposal to use state money to fund research into astrology.[122] In February, 2001, the science of vedic astrology, Jyotir Vigyan, was introduced into the curriculum of Indian universities.[123]

Education

Education in astrology is offered in most countries of the world:

United States

In the United States, astrological education is offered at institutions such as Kepler College, a liberal arts college with an emphasis on astrology in Lynnwood, Washington, near Seattle, which opened in 2001[124] and awarded its first 8 Bachelor of Arts degrees in Astrological Studies in 2004.[125] Students attending Kepler College after March 9, 2010, however, unless they are completing a course of study,[126] are not awarded degrees but certificates of completion of a course of study.[127] The degrees granted by Kepler are not recognized by national or regional accrediting agencies.[128] Other astrological organizations offer study programs and correspondence courses which, after examination, certifies astrologers.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, astrological education is offered at a number of institutions, some offering a diploma upon completion of the course and an examination. In addition, the University of Wales of Lampeter offers an MA in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology.[129]

India

In February, 2001, the "science" of vedic astrology, Jyotish Vigyan, was introduced into the curriculum of Indian universities. Undergraduate (called "graduate" in India) post-graduate and research courses of study were established. "Beneficiaries of these courses would be students, teachers, professionals from modern streams like doctors, architects, marketing, financial, economic and political analysts, etc."[123] In April, 2001 the Andhra Pradesh High Court declined to consider a petition to overturn the curriculum guideline on the ground that astrology was a pseudoscience, a decision affirmed by the Supreme Court in 2004 which declined as a matter of law to interfere with educational policy. The court noted that astrology studies were optional and that courses in astrology were offered by institutions of higher education in other countries.[130]

Some astrological organizations offer certification for astrologers

Notes

- ^ Babylonian planet names took a multitude of deity forms, most drawn from one basic deity association; for example, the basic association of Mars was with the war-god Nergal, for whom it expressed representation as the ‘the star of Nergal’.[131]

- ^ Some 'traditional astrologers' prefer to work only with the seven Classical planets, but most modern astrologers include reference to Uranus (discovered in 1781), Neptune (1846) and Pluto (1930). It is therefore conventional for astrology texts to refer to ten planets, which does not include the Earth. These, with their astrological symbols, are as follows:

![]() Sun |

Sun | ![]() Moon |

Moon | ![]() Mercury |

Mercury | ![]() Venus |

Venus | ![]() Mars |

Mars | ![]() Jupiter |

Jupiter | ![]() Saturn |

Saturn | ![]() Uranus |

Uranus | ![]() Neptune |

Neptune | ![]() Pluto

Pluto

References

- ^ Soanes (2006) 'Astrology' "The study of the movements and relative positions of celestial bodies interpreted as having an influence on human affairs and the natural world". Retrieved 16 July 2011. Also Weiner (1973) 'Astrology' by David Pingree. "...the study of the impact of the celestial bodies". Retrieved 2nd December 2009.

- ^ Koch-Westenholz (1995) Foreword and p.11.

- ^ Kassell and Ralley (2010) ‘Stars, spirits, signs: towards a history of astrology 1100–1800'; pp.67-69.

- ^ Campion (2009) pp.259-263, for the popularizing influence of newspaper astrology; pp. 239-249: for association with New Age philosophies.

- ^ Asquith and Hacking (1978) 'Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience' by Paul R. Thagard.

- ^ National Science Board (2006) Science and Engineering Indicators; ch 7: 'Science and Technology. Public Attitudes and Understanding: Belief in Pseudoscience'. National Science Foundation (2006); retrieved 19 April 2010.

- "About three-fourths of Americans hold at least one pseudoscientific belief; i.e., they believed in at least 1 of the 10 survey items[29]" ..." Those 10 items were extrasensory perception (ESP), that houses can be haunted, ghosts/that spirits of dead people can come back in certain places/situations, telepathy/communication between minds without using traditional senses, clairvoyance/the power of the mind to know the past and predict the future, astrology/that the position of the stars and planets can affect people's lives, that people can communicate mentally with someone who has died, witches, reincarnation/the rebirth of the soul in a new body after death, and channeling/allowing a "spirit-being" to temporarily assume control of a body."

- ^ Campion (2008) p.1.

- ^ Myetymology.com (2008) Etymology of the Latin word astrologia.

- ^ Partridge (1960) p.911.

- ^ Evans and Berggren (2006) p.127, n.7.

- ^ Thomas (1978) p.414-415.

- ^ Soanes (2006) 'Star' sense 1. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ Merriam-Webster (1989) p.369. Online at wordsources.info, retrieved 5th August 2011.

- ^ Tetrabiblos (Robbins ed. 1940) I.4, p.35, footnote 3.

- ^ Pliny (77 AD) illustrated the irony of the use of the term 'planet' since the planetary cycles were known to be regular and predictable: "...the seven stars, which owing to their motion we call planets, though no stars wander less than they do". Pliny the Elder (77) II.iv, p.177.

- ^ "Definition of planet". Merriam-Webster OnLine. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Manilius (77) p.87-89 (II.64-67): “the entire universe is alive in mutual concord of its elements and is driven by the pulse of reason, since a single spirit dwells in all its parts and, speeding through all things, nourishes it like a living creature”.

- ^ Alkindi (9th cent.) is clarifying this point where he says in his text On the Stellar Rays, ch.4: “... we say that one thing acts with its elemental rays on another, but according to the exquisite truth it does not act but only the celestial harmony acts”.

- ^ a b Houlding (2000) p.28: “The doctrine of the Pythagoreans was a combination of science and mysticism… Like Anaximenes they viewed the Universe as one integrated, living organism, surrounded by Divine Air (or more literally ‘Breath’), which permeates and animates the whole cosmos and filters through to individual creatures… By partaking of the core essence of the Universe, the individual is said to act as a microcosm in which all the laws in the macrocosm of the Universe are at work”.

- ^ McRitchie (2006) p.7. As one of the five 'organizational principles' of astrology that McRitchie proposes, he includes: “Nativity — ... Each individual, whether it is a person, thing, or an event, is a microcosm born at the center of its own macrocosmic universe. Each individual has its own planets, is identified with its native circumstances, and has a sensitive dependence on its initial configuration within the world of experience that is known and shared in common among other individuals. The circumstances of birth show what has begun.”

- ^ Weiss and Taruskin (2008) p.3.

- ^ Pliny the Elder (77) pp.277-8, (II.xviii.xx): "…occasionally Pythagoras draws on the theory of music, and designates the distance between the Earth and the Moon as a whole tone, that between the Moon and Mercury as a semitone, .... the seven tones thus producing the so-called diapason, i.e. a universal harmony". NASA has recently confirmed that the Sun, Moon and planets emit sounds in their orbits, each very different due to their various speeds and distances. After the sound files recorded by NASA are compressed many thousands of times, their ‘melodies’ become clearly perceptible to the human ear. The NASA sound files have been made available on YouTube: see for example 'Jupiter Sounds'; retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ^ Davis (1901) p.252. Plato’s Republic VII.XII reads: “As the eyes, said I, seem formed for studying astronomy, so do the ears seem formed for harmonious motions: and these seem to be twin sciences to one another, as also the Pythagoreans say”.

- ^ Smith (1996) p.2.

- ^ Hackett (1997) p.245 and Smith (1996) p.56.

- ^ An English translation of the Harmonica was recently published by Andrew Barker, in his Greek Musical Writings vol. II (Cambridge University Press, 2004). The work was also discussed by James Frederick Mountford in his article ‘The Harmonics of Ptolemy and the Lacuna in II, 14’ (Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 57. 1926; pp.71-95). Mountford refers to Ptolemy’s Harmonica as "the most scientific and best arranged treatise on the theory of musical scales which we possess in Greek".

- ^ Kepler (1619) 'Introduction', p.xix. “Kepler did not ascribe any direct physical influence to the celestial bodies but supposed the astrological effects to be the result of instinctive responses of individual souls to the harmonies of certain configurations or aspects. A soul was also ascribed to the Earth itself, whose response to the aspects explained their influence on the weather”. In his Tertius Interveniens, 1610, Kepler defined the horoscope as the celestial imprint imparted at birth: Ch,7: "When a human being's life is first ignited, when he now has his own life, and can no longer remain in the womb - then he receives a character and an imprint of all the celestial configurations (or the images of the rays intersecting on earth), and retains them unto his grave". See translated excerpts by Dr. Kenneth G. Negus on Cura. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Kepler (1619) Kepler's Third Law used to be known as the harmonic law. It captures the relationship between the distance of planets from the Sun, and their orbital periods. "The square of the orbital period is proportional to the cube of the mean distance from the Sun "[1]. See also Gerald James Holton, Stephen G. Brush (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure. Rutgers University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0813529085.

- ^ Bacon (1623) De Augmentis, p.351. The maxim that the stars impel but do not compel was used by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century, "following the same line of argument as St Augustine and others before him" (A history of magic by Richard Cavendish; p.66., Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977).

- ^ Bacon (1623) De Augmentis, p.351.

- ^ Campion (2008) pp.2-3.

- ^ Marshack (1972) p.81ff.

- ^ Hesiod (c. 8th cent. BCE). Hesiod’s poem Works and Days shows how the heliacal rising of constellations were used as a calendar for agricultural events, which started to acquire astrological associations, e.g.: “Fifty days after the solstice, when the season of wearisome heat is come to an end, is the right time to go sailing. Then you will not wreck your ship, nor will the sea destroy the sailors, unless Poseidon the Earth-Shaker be set upon it, or Zeus, the king of the deathless gods” (II. 663-677).

- ^ Kelley and Milone (2005) p.268.

- ^ Two texts which refer to the 'omens of Sargon' are reported in E. F. Weidner, ‘Historiches Material in der Babyonischen Omina-Literatur’ Altorientalische Studien, ed. Bruno Meissner, (Leipzig, 1928-9), v. 231 and 236.

- ^ From scroll A of the ruler Gudea of Lagash, I 17 – VI 13. O. Kaiser, Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments, Bd. 2, 1-3. Gütersloh, 1986-1991. Also quoted in A. Falkenstein, ‘Wahrsagung in der sumerischen Überlieferung’, La divination en Mésopotamie ancienne et dans les régions voisines. Paris, 1966.

- ^ Houlding (2010) Ch. 8: 'The medieval development of Hellenistic principles concerning aspectual applications and orbs'; pp.12-13.

- ^ Albiruni, Chronology (11th c.) Ch.VIII, ‘On the days of the Greek calendar’, re. 23 Tammûz; Sachau.

- ^ Houlding (2010) Ch. 6: 'Historical sources and traditional approaches'; pp.2-7.

- ^ Jung, Carl G. Letters 1906–1950, ed. Gerhard Adler, et al.(Princeton University Press: Bollingen, 1992), Letter from Jung to Freud, 12 June 1911. ISBN 9780691098951 “I made horoscopic calculations in order to find a clue to the core of psychological truth.”

- ^ Campion (2009) p.251–256: “At the same time, in Switzerland, the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) was developing sophisticated theories concerning astrology...”

- ^ Gieser, Suzanne. The Innermost Kernel, Depth Psychology and Quantum Physics. Wolfgang Pauli’s Dialogue with C.G.Jung, (Springer, Berlin, 2005) p.21 ISBN 3-540-20856-9

- ^ Campion, Nicholas. "Prophecy, Cosmology and the New Age Movement. The Extent and Nature of Contemporary Belief in Astrology."( Bath Spa University College, 2003) via Campion, Nicholas, History of Western Astrology, (Continuum Books, London & New York, 2009) p.248 p.256 ISBN 9781847252241

- ^ Holden, James, A History of Horoscopic Astrology: From the Babylonian Period to the Modern Age, (AFA 1996) p.202 ISBN 0-86690-463-8

- ^ Campion (2009) p.258: "Jungian Analyst, Liz Greene."

- ^ Hand, Robert, Horoscope Symbols (Para Research 1981) p.349 ISBN 0-914918-16-8

- ^ Hyde, Maggie. Jung and Astrology. (Aquarian/Harper Collins, 1992) p.105 ISBN 185538115X http://www.skyscript.co.uk/synchronicity.html

- ^ a b Harding, M & Harvey, C, Working with Astrology, The Psychology of Midpoints, Harmonics and Astro*Carto*Graphy, (Penguin Arkana 1990) (3rd edition pp.8–13) ISBN 1873948034

- ^ Davis, Martin, From Here to There, An Astrologer’s Guide to Astromapping, (Wessex Astrologer, England, 2008) Ch1. History, p.2 ISBN 9781902405278

- ^ Lewis, Jim & Irving, Ken, The Psychology of Astro*Carto*Graphy, (Penguin Arkana 1997) ISBN 1357918642

- ^ Humphrey Taylor. "The Religious and Other Beliefs of Americans 2003". Retrieved 2007-01-05. Also see "Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Gallup (2005): Paranormal Beliefs by Linda Lyons, retrieved 20 July 2011. For the view that belief in astrology could be much higher than Gallup reports see Campion (1997), ‘British Public Perceptions of Astrology: An Approach from the Sociology of Knowledge’ by John Bauer and Martin Durant, which reports a figure of 73%.

- ^ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=influenza Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Ζωλότας Ξενοφών. "Ελληνικές λέξεις στην αγγλική" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ For discussions of Chaucer's astrological references see A. Kitson (1996). "Astrology and English literature". Contemporary Review, October 1996. Retrieved 2006-07-17. M. Allen, J.H. Fisher. "Essential Chaucer: Science, including astrology". University of Texas, San Antonio. Retrieved 2006-07-17. A.B.P. Mattar; et al. "Astronomy and Astrology in the Works of Chaucer" (PDF). University of Singapore. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) For discussions of Shakespeare's astrological references see P. Brown. "Shakespeare, Astrology, and Alchemy: A Critical and Historical Perspective". The Mountain Astrologer, February/March 2004. F. Piechoski. "Shakespeare's Astrology". - ^ Alastair Jamieson (2008-11-30). "Secret theme behind Narnia Chronicles is based upon the stars, says new research". The Telegraph, London. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ^ Spencer, Neil. Stargazers? But of course. The Observer. (12 November 2000) [2] "Gone With the Wind, is a thinly disguised astrological allegory. Margaret Mitchell based the characters of her torrid epic on the zodiac, leaving a blatant trail of clues which were only picked up in 1978 when US astrologer Darrell Martinie was shown photocopies of notes from Mitchell's library."

- ^ "Rare JK Rowling work on the market for £25,000". The Scotsman, Edinburgh. 30 July 2010. Robert Currey. "Astrology and J K Rowling". www.astrology.co.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2011. Paul Fraser (26 May 2010). "An incredibly rare unpublished work by J.K.Rowling". Paul Fraser Collectibles.

- ^ Campion (2009) pp.244–245.

- ^ a b Gauquelin, Michel (1955). L'influence des astres : étude critique et expérimentale. Paris: Éditions du Dauphin.

- ^ a b Dean, G. and, A. Mather (1977). Recent Advances in Natal Astrology. UK: The Astrological Association. ISBN 0140223975.

- ^ Brady, Bernedette. "The Newtonian Merry-Go-Round". Geocosmic Journal. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ Tarnas, Richard (2006). Cosmos and Psyche. Imitations of a new world view. Viking. p. 660. ISBN 0670032921.

- ^ Landscheidt, T. (1973). Cosmic cybernetics: The foundations of a modern astrology. Ebertin-Verlag. p. 80. ISBN B0006CFNX6.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Addey, J. M. (1976). Harmonics in Astrology. UK: L. N. Fowler. p. 264. ISBN 852433444.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Landscheidt, T. (1988). Sun-Earth-Man: a Mesh of Cosmic Oscillations. London: The Urania Trust. p. 112. ISBN 1871989000.

- ^ Cochrane, David. "Radical Breakthroughs in 21st Century Astrology Software and the Dawn of Scientific Astrology". Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ See Rawlins (1981) where mishandling of the Gauquelin study is reported in the autobiographical account of Dennis Rawlins, co-founder of CISCOP, the investigative body tasked with critically assessing Gauquelin’s findings. Rawling's report catalogues embarrassment followed by deliberate obfuscation of the data when it became apparent that all of CISCOP’s attempts to disprove Gauquelin’s work had only served to verify the reliability of it. For one of the many controversies attached to the Carlson study see Eysenck (1986), where Eysenck's assessment was "The conclusion does not follow from the data".

- ^ Abell, G. O. (1982). "the Mars Effect". Psychology Today: 8–13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ertel, Suitbert (1993). "Puzzling Eminence Effects Might Make Good Sense" (PDF). Journal of Scientific Exploration. 7 (2): 145–154.

- ^ a b Gauquelin, Michel (1988). "Is There Really a Mars Effect?". Above & Below Journal of Astrological Studies (11): 4–7.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jerome, L. (1973). "Astrology and Modern Science: A Critical Analysis". Leonardo. 6 (2): 121–129. doi:10.2307/1572687.

- ^ Gauquelin, M.F. and M. in Foreward by J. Porte (1957). Méthodes pour étudier la Répartition des Astres dans le mouvement diurne. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gauquelin, M. (1960). Les Hommes et les Astres. Paris: Denoël.

- ^ Comité Para (1976). "Considérations critiques sur une recherche faite par M.M. Gauquelin dans le domaine des influences planétaires". Nouvelles Brèves (43): 327–343.

- ^ Gauquelin, M. (1972). "Planetary effect at the time of birth of successful professionals, an experimental control made by scientists". Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research. 3 (2): 381–389.

- ^ Dommanget, J. (1970). "Preliminary Report of the Para Committee".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Abell, G. (Spring 1983). "The Abell-Kurtz-Zelen 'Mars effect' experiments: A Reappraisal". The Skeptical Inquirer (7): 77–82.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ertel, Suitbert (1988). "Raising the Hurdle for the Athletes' Mars Effect" (PDF). Journal of Scientific Exploration. 2 (4): 53–82.

- ^ Ertel, Suitbert (1988). "Raising the Hurdle for the Athletes' Mars Effect" (PDF). Journal of Scientific Exploration. 2 (4): 76. "Correcting for selection bias by pooling all records increased empirical support for the stronger version of this claim; the data have overcome, in spite of disturbing effects of bias, the higher methodological hurdle."

- ^ Benski, Claude; et al. (1996). The "Mars Effect": A French Test of Over 1,000 Sports Champions. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879759887.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ Irving, K. (1996). The Tenacious Mars Effect. London: The Urania Trust.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Irving, Ken. "Misunderstandings About the Gauquelin Planetary Effects". Planetos. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- ^ Muller, Richard (2010). "Web site of Richard A. Muller, Professor in the Department of Physics at the University of California at Berkeley,". Retrieved 2011-08-02.My former student Shawn Carlson published in Nature magazine the definitive scientific test of Astrology.

Maddox, Sir John (1995). "John Maddox, editor of the science journal Nature, commenting on Carlson's test". Retrieved 2011-08-02."... a perfectly convincing and lasting demonstration." - ^ Carlson, Shawn (1985). "A double-blind test of astrology" (PDF). Nature. 318 (6045): 419–425. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..419C. doi:10.1038/318419a0.

- ^ Eysenck (1986). Eysenck's assessment was to find: "The conclusion does not follow from the data".

- ^ a b Eysenck, H.J., and Nias, D.K.B. (1982)

- ^ a b c G. Phillipson, Astrology in the Year Zero. Flare Publications (London, 2000) ISBN 0-9530261-9-1

- ^ a b c M. Harding. "Prejudice in Astrological Research". Correlation, Vol 19(1).

- ^ K. Irving. "Science, Astrology and the Gauquelin Planetary Effects".

- ^ M. Urban-Lurain, Introduction to Multivariate Analysis, Astrological Research Methods, Volume 1: An ISAR Anthology. International Society for Astrological Research (Los Angeles 1995) ISBN 0-9646366-0-3

- ^ G. Perry, How do we Know What we Think we Know? From Paradigm to Method in Astrological Research, Astrological Research Methods, Volume 1: An ISAR Anthology. International Society for Astrological Research (Los Angeles 1995) ISBN 0-9646366-0-3

- ^ a b "Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists". The Humanist, September/October 1975.

- ^ "Activities With Astrology". Astronomical society of the Pacific.

- ^ Bob Marks. "Astrology for Skeptics".

- ^ Bok, Bart J. (1982). "Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists". In Patrick Grim (ed.). Philosophy of Science and the Occult. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 14–18. ISBN 0873955722.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sagan, Carl. "Letter." The Humanist 36 (1976): 2

- ^ Sagan, Carl. The Demon Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1996), pp. 302-303.

- ^ Jung, C.G., (1952), Synchronicity - An Acausal Connecting Principle (London: RKP English edition, 1972), p.36. "synchronicity ...(is)...a coincidence in time of two or more casually unrelated events which have the same or similar meaning, in contrast to 'synchronism', which simply means the simultaneous occurrence of two events".

- ^ Maggie Hyde, Jung and Astrology; p.24–26; 121ff. (London: The Aquarian Press, 1992). "As above, so below. Early in his studies, Jung came across the ancient macrocosm-microcosm belief with its enduring theme of the organic unity of all things"; p.121.

- ^ Cornelius (2003). Cornelius’s thesis is - although divination is rarely addressed by astrologers, it is an obvious descriptive tag "despite all appearances of objectivity and natural law. It is divination despite the fact that aspects of symbolism can be approached through scientific method, and despite the possibility that some factors in horoscopy can arguably be validated by the appeal to science." ('Introduction', p.xxii).

- ^ Dr. P. Seymour, Astrology: The Evidence of Science. Penguin Group (London, 1988) ISBN 0-14-019226-3

- ^ Frank McGillion. "The Pineal Gland and the Ancient Art of Iatromathematica".

- ^ Huygens, Christiaan, Cosmotheoros p. 68 of the English translation

- ^ Richard Dawkins (31 December 1995). "The Real Romance in the Stars". London: The Independent, December 1995.

- ^ "Astronomical Pseudo-Science: A Skeptic's Resource List". Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

- ^ "British Physicist Debunks Astrology in Indian Lecture". Associated Press.

- ^ "Ariz. Astrology School Accredited". The Washington Post. 2001-08-27.

- ^ Hartmann, P (2006). "The relationship between date of birth and individual differences in personality and general intelligence: A large-scale study". Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (7): 1349–1362. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.017.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Eysenck, H.J., and Nias, D.K.B. (1982) pp.42-48.

- ^ About.com: Is Astrology a Pseudoscience? Examining the Basis and Nature of Astrology

- ^ Saliba, George (1994b). A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York University Press. pp. 60 & 67–69. ISBN 0814780237.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Catarina Belo, Catarina Carriço Marques de Moura Belo, Chance and determinism in Avicenna and Averroës, p.228. Brill, 2007. ISBN 9004155872.

- ^ George Saliba, Avicenna: 'viii. Mathematics and Physical Sciences'. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, 2011, available at http://www.iranica.com/articles/avicenna-viii

- ^ Livingston, John W. (1971). "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: A Fourteenth Century Defense against Astrological Divination and Alchemical Transmutation". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 91 (1): 96–103. doi:10.2307/600445. JSTOR 600445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Livingston, John W. (1971). "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah: A Fourteenth Century Defense against Astrological Divination and Alchemical Transmutation". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 91 (1): 96–103 [99]. doi:10.2307/600445. JSTOR 600445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "In countries such as India, where only a small intellectual elite has been trained in Western physics, astrology manages to retain here and there its position among the sciences." David Pingree and Robert Gilbert, "Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times". Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008

- ^ Mohan Rao, Female foeticide: where do we go? Indian Journal of Medical Ethics Oct-Dec2001-9(4) [3]

- ^ Kaufman, Michael T. (1998-12-23). "BV Raman Dies". New York Times, December 23, 1998. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ Dipankar Das, May 1996. "Fame and Fortune". Retrieved 2009-05-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ V.K. Choudhry and K. Rajesh Chaudhary, 2006, Systems' Approach (astrology) Systems' Approach for Interpreting Horoscopes, Fourth Revised Edition, Sagar Publications, New Delhi, India. ISBN 81-7082-017-0

- ^ Indian Astrology vs Indian Science

- ^ a b "Guidelines for Setting up Departments of Vedic Astrology in Universities Under the Purview of University Grants Commission". Government of India, Department of Education. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

There is an urgent need to rejuvenate the science of Vedic Astrology in India, to allow this scientific knowledge to reach to the society at large and to provide opportunities to get this important science even exported to the world,

- ^ McClure, Robert (July 23, 2001). "Astrology school sets off controversy". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "Kepler College First Graduation, October 10, 2004". StarIQ.Com. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "Degree-Granting Authorization". Kepler College. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

Kepler College Authorization Degree-Granting Authorization Kepler College is authorized by the Washington Higher Education Coordinating Board and through March 9, 2010, the College met the requirements and minimum standards established for degree-granting institutions under the Degree Authorization Act. Students attending the college between March 9, 2000 and March 9, 2010 (and extended to March 9, 2012 to include students completing the teach-out of their degrees) earned Washington State authorized degrees in: Associate of Arts Bachelor of Arts Master of Arts in: Eastern and Western Traditions The History, Philosophy and Transmission of Astrology

- ^ "Certificate Program Information". Kepler College. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "Was your degree program accredited?". Kepler College. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "MA in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology". Trinity Saint David, The University of Wales. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ "Introduction of Vedic astrology courses in varsities upheld." The Hindu, May 06, 2004

- ^ Brown (2000) pp.63-72.

Bibliography

- Alkindi, c.9th cent. De Radiis Stellicis (On the Stellar Rays), translated by Robert Zoller. London: New Library, 2004. (3rd digital ed.)

- Armstrong, J. Scott, 1982. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 'Barriers to Scientific Contributions: The Author’ s Formula'. Cambridge University Press. Vol. 5, pp.197-199 (June 1982). ISSN 0140525X.

- Asquith, Peter, and Hacking, Ian., 1978. Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, vol. 1. Philosophy of Science Association. ISBN 9780917586057.

- Brown, David, 2000. Mesopotamian planetary astronomy-astrology. Cuneiform Monographs 18. Groningen: Styx Publications. ISBN 9056930362.

- Campion, Nicholas, (ed.) 1997. Culture and Cosmos. Sophia Centre Press. Vol. 1, no. 1. ISSN 13686534.

- Campion, Nicholas, 2008. A History of Western Astrology, Vol. 1, The Ancient World (first published as The Dawn of Astrology: a Cultural History of Western Astrology. London: Continuum. ISBN 9781441181299.

- Campion, Nicholas, 2009. A History of Western Astrology, Vol. 2, The Medieval and Modern Worlds. London: Continuum. ISBN 9781441181299.

- Cornelius, Geoffrey, 2003. The Moment of Astrology: Origins in Divination. Bournemouth: Wessex. (Originally published by Penguin Arkana, 1994). ISBN 902405110.

- Davis, Henry, 1901. The Republic The Statesman of Plato. London: M. W. Dunne 1901; Nabu Press reprint, 2010. ISBN 9781146979726.

- Evans, James, and Berggren, J. Lennart, 2006. Geminos's introduction to the phenomena. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691123394.

- Eysenck, H.J., and Nias, D.K.B., 1982 Astrology: Science or Superstition? Penguin Books. ISBN 0140223975.

- Eysenck, H.J., 1986 Astrological Journal 'Critique of 'A double-blind test of astrology'; vol xviii (3), April 1986.

- Hackett, Jeremiah, 1997. Roger Bacon and the sciences: commemorative essays. Brill. ISBN 9789004100152.

- Hesiod (c. 8th cent. BCE) . Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica translated by Evelyn-White, Hugh G., 1914. Loeb classical library; revised edition. Cambridge: Harvard Press, 1964. ISBN 9780674990630.

- Houlding, Deborah, 2000. The Traditional Astrologer. London: Ascella. Issue 19 (January 2000). ISSN 13694826.

- Houlding, Deborah, 2010. Essays on the history of western astrology. Nottingham: STA. ISBN 1899503559.

- Kassell, Lauren, and Ralley, Robert, 2010. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. Volume 41, issue 2 (June 2010). ISSN: 13698486

- Kelley, David, H. and Milone, E.F., 2005. Exploring ancient skies: an encyclopedic survey of archaeoastronomy. Heidelberg / New York: Springer. ISBN 9780387953106.

- Kepler, Johannes, 1619. The Harmony of the World, translated by E.J. Aiton, A.M. Duncan and J.V. Field (1997). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0871692090.

- Koch-Westenholz, Ulla, 1995. Mesopotamian astrology. Volume 19 of CNI publications. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 9788772892870.

- Manilius, Marcus, c.10 AD. Astronomica. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674995163.

- Marshack, Alexander, 1972. The roots of civilization: the cognitive beginnings of man's first art, symbol and notation. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9781559210416.

- McRitchie, Ken, 2006. Correlation: Journal of Research in Astrology ‘Astrology and the social sciences: looking inside the black box of astrology theory’ Correlation: (2006), Vol 24(1), pp. 5-20. Online at www.theoryofastrology.com.

- Merriam-Webster, 1989. Webster's word histories. Springfield, Massachusetts, USA: Merriam-Webster. ISBN 9780877790488.

- Partridge, Eric, 1960. Origins: a short etymological dictionary of modern English (2nd edition). London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0674993640.

- Pliny the Elder, 77AD. Natural History, books I-II, translated by H. Rackham (1938). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674993640.

- Robbins, Frank E. (ed.) 1940. Ptolemy Tetrabiblos. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library). ISBN 0-674-99479-5.

- Rawley, William, 1858. The Works of Francis Bacon. Longmans 1858. Boston: Adamant Media. ISBN 9781402182211. Digitized by Harvard University, 2006; online at Google books.)

- Rawlins, Dennis, 1981. Fate Magazine 'sTARBABY'; pp.67-98. No.34, October 1981. Reproduced on the Cura website, retrieved 11 August 2011.

- Schuon, Frithjof, 1959. Gnosis: divine wisdom. J. Murray and Sons. Republished: World Wisdom Inc 2006. ISBN 9781933316185.

- Smith, Mark A., 2006. Ptolemy's theory of visual perception: an English translation of the Optics. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871698629.

- Soanes, Catherine, (ed.) 2006. The Oxford Dictionary of English 2nd ed. Oxford University Press: Oxford. ISBN 3411021446.

- Thomas, Keith, 1978. Religion and the decline of magic. London: Peregrine Books. ISBN 9780140551501.

- Wiener, Phillip P., (ed.) 1973. The Dictionary of the History of Ideas vol.I. Scribner: New York. ISBN 0684132931.

- Weiss, Piero and Taruskin, Richard, 2008. Music in the Western World: a history in documents. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780534585990.