British Raj

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

The British Raj (known from 1911 as the Indian Empire) was the period during which most of the Indian subcontinent, or present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, were under the colonial authority of the British Empire (Undivided India). Since the independence of these countries their pre-independent existence has been loosely termed British India, although prior to Independence that term referred only to those portions of the subcontinent under direct rule by the British administration in Delhi and previously Calcutta, as opposed to the Princely States which were directly under the rule of the nawabs and rajas and only indirectly under British control. Aden was part of "British India" from 1839 and Burma from 1886; both became separate crown colonies of the British Empire in 1937. It lasted from 1858, when the rule of the British East India Company was transferred to the Crown, until 1947, when pre-independence India was partitioned into two sovereign states, India and Pakistan. Although Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) is peripheral to the Indian subcontinent, it is not counted part of the Raj, as it was ruled as a Crown Colony from London rather than by the Viceroy of India as a part of the Indian Empire. French India and Portuguese India consisted of small coastal enclaves governed by France and Portugal, respectively; they were integrated into India after Indian independence.

History

On December 31, 1600, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted a royal charter to the British East India Company to carry out trade with the East. Company ships first arrived in India in 1608, docking at Surat in modern-day Gujarat. Four years later, British traders defeated the Portuguese at the Battle of Swally, gaining the favour of the Mughal emperor Jahangir in the process. In 1615, King James I sent Sir Thomas Roe as his ambassador to Jahangir's court, and a commercial treaty was concluded in which the Mughals allowed the Company to build trading posts in India in return for goods from Europe. The Company traded in such commodities as cotton, silk, saltpeter, indigo, and tea.

By the mid-1600s, the Company had established trading posts or "factories" in major Indian cities such as Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras in addition to their first factory at Surat (built in 1612). In 1670, King Charles II granted the company the right to acquire territory, raise an army, mint its own money, and exercise legal jurisdiction in areas under its control.

By the last decade of the 17th century, the Company was arguably its own "nation" on the Indian subcontinent, possessing considerable military might and ruling three presidencies.

The British first established a territorial foothold in the Indian subcontinent when Company-funded soldiers commanded by Robert Clive defeated the Bengali Nawab Siraj Ud Daulah at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Bengal's riches were expropriated, the East India Company monopolised Bengali trade and Bengal became a British protectorate directly under its rule. Bengali farmers and craftsmen were obliged to render their labour for minimal remuneration while their collective tax burden increased greatly. As a consequence, the famine of 1769 to 1773 cost the lives of 10 million Bengalis. A similar catastrophe occurred almost a century later, after Britain had extended its rule across the Indian subcontinent, when 40 million Indians perished from famine amidst the collapse of India's indigenous industries.

Building the Raj: British expansion across India

The Regulating Act of 1773 that was passed by the British Parliament asserted Whitehall's ultimate control of the company. It also established the post of governor-general of India, the first occupant of which was Warren Hastings. Further acts, such as the Charter Acts of 1813 and 1833, further defined the relationship of the Company and the British government.

At the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General Lord Wellesley began expanding the Company's domain on a large scale, defeating Tippoo Sultan (also spelled Tipu Sultan), annexing Mysore in southern India, and removing all French influence from the subcontinent. In the mid-19th century, Governor-General Lord Dalhousie launched perhaps the Company's most ambitious expansion, defeating the Sikhs in the Anglo-Sikh Wars (and annexing Punjab with the exception of the Phulkian States) and subduing Burma in the Second Burmese War. He also justified the takeover of small princely states such as Satara, Sambalpur, Jhansi, and Nagpur by way of the doctrine of lapse, which permitted the Company to annex any princely state whose ruler had died without a male heir. The annexation of Oudh in 1856 proved to be the Company's final territorial acquisition, as the following year saw the boiling over of Indian grievances toward the so-called "Company Raj".

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The "Indian Mutiny" or "War of Freedom"

On May 10, 1857, soldiers of the British Indian Army (known as "sepoys," from Urdu/Persian sipaahi or sepaahi = "soldier"), drawn from the native Hindu and Muslim population, mutinied in Meerut, a cantonment eighty kilometres northeast of Delhi. The rebels marched to Delhi to offer their services to the Mughal emperor, and soon much of north and central India was plunged into a year-long insurrection against the English East India Company. Many native regiments and Indian kingdoms joined the revolt, while other Indian units and Indian kingdoms backed the English commanders and the HEIC.

Causes of the Rebellion

The uprising, which seriously threatened British rule in India, was undoubtedly the culmination of mounting Indian resentment toward British social and political policies over many decades. Until the rebellion, the British had succeeded in suppressing numerous riots and "tribal" wars or in accommodating them through concessions, but two factors – one a trend and the other a single event – triggered the violent explosion of wrath in 1857.

The trend was the policy of annexation pursued by Governor-General Lord Dalhousie, based mainly on his "Doctrine of Lapse", which held that princely states would be merged into company-ruled territory in case a ruler died without direct heir. This denied the native rulers the right to adopt an heir in such an event; adoption had been pervasive practise in the Hindu states hitherto, sanctioned both by religion and by secular tradition. The states annexed under this doctrine included such major kingdoms as Satara, Thanjavur, Sambhal, Jhansi, Jetpur, Udaipur, and Baghat. Additionally, the company had annexed, without pretext, the rich kingdoms of Sind in 1843 and Oudh in 1856, the latter a wealthy princely state that generated huge revenue and represented a vestige of Mughal authority. This greed for land, especially in a group of small-town and middle-class British merchants, whose parvenu background was increasingly evident and galling to Indians of rank, had alienated a large section of the landed and ruling aristocracy, who were quick to take up the cause of evicting the merchants once the revolt was kindled.

The spark that lit the fire was the result of a very convincing, though untrue, rumour about a British blunder in using new cartridges for the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle that were greased with animal fat, rumoured to now be a combination of pig-fat and cow-fat. This was offensive to the religious beliefs of both Muslim and Hindu sepoys respectively, who refused to use the cartridges and, under provocation, finally mutinied against their British officers.

Course of the Rebellion

The rebellion soon engulfed much of North India, including Oudh and various areas that had lately passed from the control of Maratha princes to the company. The unprepared British were terrified, without replacements for the casualties. The rebellion inflicted havoc on Indians and the community suffered humiliation and triumph in battle as well, although the final outcome was victory for the British. Isolated mutinies also occurred at military posts in the centre of the subcontinent. The last major sepoy rebels surrendered on June 21, 1858, at Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh), one of the principal centres of the revolt. A final battle was fought at Sirwa Pass on May 21, 1859, and the defeated rebels fled into Nepal.

Although the rebellious sepoys fought with great bravery, the British were victorious due to superior leadership and organisation, as well as the fact that the majority of the sepoys remained loyal to the British. The Sikh sepoys were the most reliable of all the native troops, partly because they were not from the region of the mutinity and had no affinity to the local region and thus were somewhat suspicious of the mutineers. Another reason was that they had a long tradition of military service, such that they felt bound to follow the orders of those to whom they had pledged their service.

During the rebellion, Gurkhas fought on the British side. The 2nd Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles) defended Hindu Rao's house for over three months, losing 327 out of 490 men. The 60th Rifles (later the Royal Green Jackets) fought alongside the Sirmoor Rifles and were so impressed that following hostilities they insisted 2nd Gurkhas be awarded the honours of adopting their distinctive rifle green uniforms with scarlet edgings and rifle regiment traditions and that they should hold the title of riflemen rather than sepoys. Twelve Nepalese regiments also took part in the relief of Lucknow under the command of Shri Teen (3)Maharaja Maharana Jung Bahadur of Nepal.

Most areas ruled by native princes remained largely untouched by the rebellion; in particular, Rajasthan and the maratha states of central India, with the exception of Gwalior, remained calm. Punjab was another major area loyal to the British throughout the rebellion, and the main source of supplies and fighting men for them. Significantly, the rebellion also did not spread to other parts of the subcontinent, most notably the south, which was a bastion of British power.

There has been much subsequent debate about the correct labelling of this event in the history of the Raj. Although it has gone down in the imperial annals as "the Indian Mutiny" or the Sepoy Rebellion, many modern-day Indians, and others besides, feel that this is an inappropriate term for what they see as the first serious independence movement in India. The spontaneous and widespread rebellion later fired the imagination of the nationalists who would debate the most effective method of protest against British rule. For them, the rebellion represented the first Indian attempt at gaining independence. In 2005, a film was made about this indian uprising- 'The Rising'

Post-rebellion developments

The rebellion was a major turning point in the history of modern India. In May 1858, the British exiled Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II (r. 1837-1857) to Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), after executing most of his family, thus formally liquidating the Mughal Empire.

Bahadur Shah Zafar, known as the Poet King, contributed some of Urdu's most beautiful poetry, with the underlying theme of the freedom struggle. The Emperor was not allowed to return and died in solitary confinement in 1862. The Emperor's three sons, also involved in the War of Independence, were arrested and beheaded at the Khooni Derwaza (Blood Gate) in Delhi by Major Hudson of the British Army, and their heads were then put up for display at the Delhi Court.

Cultural and religious centers were closed down, properties and estates were confiscated. At the same time, the British abolished the British East India Company and replaced it with direct rule under the British Crown. In proclaiming the new direct-rule policy to "the Princes, Chiefs, and Peoples of India," Queen Victoria (who was given the title Empress of India in 1877) promised equal treatment under British law, but Indian mistrust of British rule had become a legacy of the 1857 rebellion.

Many existing economic and revenue policies remained virtually unchanged in the post-1857 period, but several administrative modifications were introduced, beginning with the creation in London of a cabinet post, the Secretary of State for India. The governor-general (called viceroy when acting as representative to the nominally sovereign "princely states" or "native states"), headquartered in Calcutta, ran the administration in India, assisted by executive and legislative councils. Beneath the governor-general were the governors of Provinces of India, who held power over the division and district officials, who formed the lower rungs of the Indian Civil Service. For decades the Indian Civil Service was the exclusive preserve of the British-born, as were the superior ranks in such other professions as law and medicine. The British administrators were imbued with a sense of duty in ruling India and were rewarded with good salaries, high status, and opportunities for promotion. Not until the 1910s did the British reluctantly permit a few Indians into their cadre as the number of English-educated Indians rose steadily.

The Viceroy of India announced in 1858 that the government would honour former treaties with princely states and renounced the "Doctrine of Lapse," whereby the East India Company had annexed territories of rulers who died without male heirs. About 40 percent of Indian territory and 20-25 percent of the population remained under the control of 562 princes notable for their religious (Islamic, Hindu, Sikh and other) and ethnic diversity. Their propensity for pomp and ceremony became proverbial, while their domains, varying in size and wealth, lagged behind sociopolitical transformations that took place elsewhere in British-controlled India.

A more thorough re-organisation was effected in the constitution of army and government finances. Shocked by the extent of solidarity among Indian soldiers during the rebellion, the government separated the army into the three presidencies.

The Indian Councils Act of 1861 restored legislative powers to the presidencies, which had been given exclusively to the governor-general by the Charter Act of 1833.

British attitudes toward Indians shifted from relative openness to insularity and xenophobia, even against those with comparable background and achievement as well as loyalty. British families and their servants lived in cantonments at a distance from Indian settlements. Private clubs where the British gathered for social interaction became symbols of exclusivity and snobbery that refused to disappear decades after the British had left India. In 1883 the government of India attempted to remove race barriers in criminal jurisdictions by introducing a bill empowering Indian judges to adjudicate offences committed by Europeans. Public protests and editorials in the British press, however, forced the viceroy George Robinson, First Marquess of Ripon, (who served from 1880 to 1884), to capitulate and modify the bill drastically. The Bengali "Hindu intelligentsia" learned a valuable political lesson from this "white mutiny": the effectiveness of well-orchestrated agitation through demonstrations in the streets and publicity in the media when seeking redress for real and imagined grievances.

Post-1857 India also experienced a period of unprecedented calamity when the region was swept by a series of frequent and devastating famines, among the most catastrophic on record. Approximately 25 major famines spread through states such as Tamil Nadu in South India, Bihar in the north, and Bengal in the east in the latter half of the 19th century, killing between 30-40 million Indians. The famines were a product both of uneven rainfall and British economic and administrative policies, which since 1857 had led to the seizure and conversion of local farmland to foreign-owned plantations, restrictions on internal trade, heavy taxation of Indian citizens to support unsuccessful British expeditions in Afghanistan (see Second Anglo-Afghan War), inflationary measures that increased the price of food, and substantial exports of staple crops from India to the United Kingdom. (Dutt, 1900 and 1902; Srivastava, 1968; Sen, 1982; Bhatia, 1985.) Some British citizens such as William Digby agitated for policy reforms and famine relief, but Lord Lytton, son of the poet Edward Bulwer-Lytton and the governing British viceroy in India, opposed such changes in the belief that they would stimulate shirking by Indian workers. Native industries in India were also decimated in the aftermath of the 1857 rebellion, particularly during the three decades from 1870 to 1900. The famines continued until independence in 1947, with the Bengal Famine of 1943-44 -- among the most devastating -- killing 3-4 million Indians during World War II.

Beginnings of self-government

The first steps were taken toward self-government in British India in the late 19th century with the appointment of Indian counsellors to advise the British viceroy and the establishment of provincial councils with Indian members; the British subsequently widened participation in legislative councils with the Indian Councils Act of 1892.

The Government of India Act of 1909 -- also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms (John Morley was the secretary of state for India, and Gilbert Elliot, fourth earl of Minto, was viceroy) -- gave Indians limited roles in the central and provincial legislatures, known as legislative councils. Indians had previously been appointed to legislative councils, but after the reforms some were elected to them. At the centre, the majority of council members continued to be government-appointed officials, and the viceroy was in no way responsible to the legislature. At the provincial level, the elected members, together with unofficial appointees, outnumbered the appointed officials, but responsibility of the governor to the legislature was not contemplated. Morley made it clear in introducing the legislation to the British Parliament that parliamentary self-government was not the goal of the British government.

The Morley-Minto Reforms were a milestone. Step by step, the elective principle was introduced for membership in Indian legislative councils. The "electorate" was limited, however, to a small group of upper-class Indians. These elected members increasingly became an "opposition" to the "official government." Communal electorates were later extended to other communities and made a political factor of the Indian tendency toward group identification through religion. The practice created certain vital questions for all concerned. The intentions of the British were questioned. How humanitarian was their concern for the minorities? Were separate electorates a manifestation of "divide and rule"?

For Muslims it was important both to gain a place in all-India politics and to retain their Muslim identity, objectives that required varying responses according to circumstances, as the example of Muhammed Ali Jinnah illustrates. Jinnah, who was born in 1876, studied law in England and began his career as an enthusiastic liberal in Congress on returning to India. In 1913 he joined the Muslim League, which had been shocked by the 1911 annulment of the partition of Bengal into cooperating with Congress to make demands on the British. Jinnah continued his membership in Congress until 1919. During this dual membership period, he was described by a leading Congress spokesperson as the "ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity."

After World War I

India's important contributions to the efforts of the British Empire in World War I stimulated further demands by Indians and further response from the British. The Congress Party and the Muslim League met in joint session in December 1916. Under the leadership of Jinnah and Pandit Motilal Nehru (father of Jawaharlal Nehru), unity was preached and a proposal for constitutional reform was made that included the concept of separate electorates. The resulting (see[[1]]) Congress-Muslim League Pact (often referred to as the Lucknow Pact) was a sincere effort to compromise. Congress accepted the separate electorates demanded by the Muslim League, and the Muslim League joined with Congress in demanding self-government. The pact was expected to lead to permanent and constitutional united action.

In August 1917, the British government formally announced a policy of "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration and the gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the progressive realization of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire." Constitutional reforms were embodied in the Government of India Act 1919, also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms (Edwin Samuel Montagu was the United Kingdom's Secretary of State for India; the Viscount Chelmsford was viceroy). These reforms represented the maximum concessions the British were prepared to make at that time. The franchise was extended, and increased authority was given to central and provincial legislative councils, but the viceroy remained responsible only to London.

The changes at the provincial level were significant, as the provincial legislative councils contained a considerable majority of elected members. In a system called "dyarchy," based on an approach developed by Lionel Curtis, the nation-building departments of government -- agriculture, education, public works, and the like -- were placed under ministers who were individually responsible to the legislature. The departments that made up the "steel frame" of British rule -- finance, revenue, and home affairs -- were retained by executive councillors who were often (but not always) British, and who were responsible to the governor.

The 1919 reforms did not satisfy political demands in India. The British repressed opposition, and restrictions on the press and on movement were reenacted. An apparently unwitting example of violation of rules against the gathering of people led to the massacre at Jalianwala Bagh in Amritsar in April 1919. This tragedy galvanized such political leaders as Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) and Mohandas Karamchand "Mahatma" Gandhi (1869-1948) and the masses who followed them to press for further action.

The Allies' post-World War I peace settlement with Turkey provided an additional stimulus to the grievances of the Muslims, who feared that one goal of the Allies was to end the caliphate of the Ottoman sultan. After the end of the Mughal Empire, the Ottoman caliph had become the symbol of Islamic authority and unity to Indian Sunni Muslims. A pan-Islamic movement, known as the Khilafat Movement, spread in India. It was a mass repudiation of Muslim loyalty to British rule and thus legitimated Muslim participation in the Indian nationalist movement. The leaders of the Khilafat Movement used Islamic symbols to unite the diverse but assertive Muslim community on an all-India basis and bargain with both Congress leaders and the British for recognition of minority rights and political concessions.

Muslim leaders from the Deoband and Aligarh movements joined Gandhi in mobilising the masses for the 1920 and 1921 demonstrations of civil disobedience and non-cooperation in response to the massacre at Amritsar. At the same time, Gandhi endorsed the Khilafat Movement, thereby placing many Hindus behind what had been solely a Muslim demand.

Despite impressive achievements, however, the Khilafat Movement failed. Turkey rejected the caliphate and became a secular state. Furthermore, the religious, mass-based aspects of the movement alienated such Western-oriented constitutional politicians as Jinnah, who resigned from Congress. Other Muslims also were uncomfortable with Gandhi's leadership. The British historian Sir Percival Spear wrote that "a mass appeal in his Gandhi's hands could not be other than a Hindu one. He could transcend caste but not community. The Hindu devices he used went sour in the mouths of Muslims". In the final analysis, the movement failed to lay a lasting foundation of Indian unity and served only to aggravate Hindu-Muslim differences among masses that were being politicised. Indeed, as India moved closer to the self-government implied in the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, rivalry over what might be called the spoils of independence sharpened the differences between the communities.

Further reform

The political picture in India was not at all clear when the mandated decennial review of the Government of India Act of 1919 became due in 1929. Prospects of further constitutional reforms spurred greater agitation and a frenzy of demands from different groups (See Nehru Report) . The Simon Commission headed by Sir John Simon, who recommended further constitutional change, but it was not until 1935 that a new Government of India Act was passed. The Indian Round Table Conferences 1931-1933 were held in London, at which a wide variety of interests from India were represented. The major disagreement concerned the continuation of separate electorates, which Gandhi and Congress strongly opposed. As a result, the decision was forced on the British government. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald issued his "communal award," which continued the system of separate electorates at both the central and the provincial level.

The principal result of the act was provincial autonomy. The dyarchical system was discontinued, and all subjects were placed under ministers who were individually and collectively responsible to the former legislative councils, which were renamed legislative assemblies. (In a few provinces, including Bengal, a bicameral system was established; the upper house continued to be called a legislative council.) Almost all assembly members were elected, with the exception of some special and otherwise unrepresented groups. After the elections, provincial chief ministers and cabinets took office, although the governors had limited emergency powers. Sindh was separated from Bombay and became a province. The 1919 reforms had earlier been introduced in the North-West Frontier Province. Balochistan, however, retained special status; it had no legislature and was governed by an "agent general to the governor general." At the centre, the act essentially provided for the establishment of dyarchy, but it also provided for a federal system that included the princes. The princes refused to join a system that might force them to accept decisions made by elected politicians. Thus, the full provisions of the 1935 act did not come into force at the centre.

World War II and the End of the Raj

At the start of World War II an agreement was reached between the British government and the Indian independence movement whereby India would be granted independence once victory was gained over the Axis Powers, in exchange for India's full co-operation in the war. Millions of Indians joined the military; it was the largest all-volunteer army in the history of the world.

At midnight on August 14, 1947 Pakistan (then also including modern Bangladesh) was granted independence. India was granted independence the following day.

Most people would give these dates as the end of the British Raj. However, some people argue that it continued until 1950 in India when it adopted a republican constitution.

Provinces

At the time of independence, British India consisted of the following provinces:

- Ajmer-Merwara-Kekri

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Assam

- Baluchistan

- Bengal

- Bihar

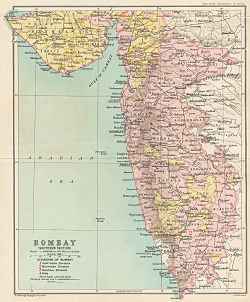

- Bombay Province - Bombay

- Central Provinces and Berar

- Coorg

- Delhi Province - Delhi Madras Province - Madras

- North-West Frontier Province

- Panth-Piploda

- Orissa

- Punjab

- Sindh

- United Provinces (Agra and Oudh)

Eleven provinces (Assam, Bengal, Bihar, Bombay, Central Provinces, Madras, North-West Frontier, Orissa, Punjab, and Sindh) were headed by a governor. The remaining six (Ajmer Merwara, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Baluchistan, Coorg, Delhi, and Panth-Piploda) were governed by a chief commissioner.

There were also several hundred Princely States, under British protection but ruled by native rulers. Among the most notable of these were Jaipur, Hyderabad, Mysore, and Jammu and Kashmir.

See also

- India Office

- Governor-General of India

- Indian Civil Service

- Government of India Act

- Partition of India

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

- Anglo-Indian cuisine

References

- Bhatia, B.M. (1985) Famines in India: A study in Some Aspects of the Economic History of India with Special Reference to Food Problem, Delhi: Konark Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Bowle, John, The Imperial Achievement, Secker & Warburg, London, 1974, ISBN 436-05905-3

- Coates, Tim, (series editor), The Amritsar Massacre 1919 - General Dyer in the Punjab (Official Reports, including Dyer's Testimonies), Her Majesty's Stationary Office (HMSO) 1925, abridged edition, 2000, ISBN 0-11-702412-0

- Dutt, Romesh C. Open Letters to Lord Curzon on Famines and Land Assessments in India, first published 1900, 2005 edition by Adamant Media Corporation, Elibron Classics Series, ISBN 1402151152.

- Dutt, Romesh C. The Economic History of India under early British Rule, first published 1902, 2001 edition by Routledge, ISBN 0415244935

- Forbes, Rosita, India of the Princes', London, 1939.

- Forrest, G.W., CIE, (editor), Selections from The State Papers of the Governors-General of India - Warren Hastings (2 vols), Blackwell's, Oxford, 1910.

- Grant, James, History of India, Cassell, London, n/d but c1870. Several volumes.

- James, Lawrence, Raj - The Making and Unmaking of British India, London, 1997, ISBN 0-316-64072-7

- Keay, John, The Honourable Company - A History of the English East India Company, HarperCollins, London, 1991, ISBN 0-00-217515-0

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey, India Britannica, Book Club Associates, UK, 1983.

- Morris, Jan, with Simon Winchester, Stones of Empire - The Buildings of the Raj, Oxford University Press, 1st edition 1983 (paperback edition 1986, ISBN 0-19-282036-2

- Sen, Amartya, Poverty and Famines : An Essay on Entitlements and Deprivation, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1982

- Srivastava, H.C., The History of Indian Famines from 1858-1918, Sri Ram Mehra and Co., Agra, 1968.

- Voelcker, John Augustus, Report on the Improvement of Indian Agriculture, Indian Government publication, Calcutta, 2nd edition, 1897.

- Woodroffe, Sir John, Is India Civilized - Essays on Indian Culture, Madras, 1919.

- India, Pakistan

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

- Bibliography