Macedonians (ethnic group): Difference between revisions

Undo POV. Discuss AND REACH CONSENSSUS. You have not in. |

|||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

{{See also|Slavic-speakers of Greek Macedonia|Slavic dialects of Greece}} |

{{See also|Slavic-speakers of Greek Macedonia|Slavic dialects of Greece}} |

||

The existence of an ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece is rejected by the Greek government. The number of people speaking [[ |

The existence of an ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece is rejected by the Greek government. The number of people speaking the [[Slavic dialects of Greece|Macedonian Slavic dialects]] has been estimated between 100,000 and 300,000.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=FnxZfdDXC7gC&pg=PA234&dq=number+of+slavophone+greece&hl=en&ei=YXlQTqK9GsfDswbp66jBAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=number%20of%20slavophone%20greece&f=false Bulgaria and Europe: Shifting Identities, East European and Eurasian Studies, Author Stefanos Katsikas, Publisher Anthem Press, 2010, ISBN 1843318466, p. 234.]</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=GR|title=Ethnologue report for Greece|work=[[Ethnologue]]|accessdate=2009-02-13}}</ref><ref>http://www.britannica.com/new-multimedia/pdf/wordat077.pdf</ref><ref>[http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?LangID=42&menu=004 UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile<!--Bot-generated title-->].</ref><ref>[http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?LangID=37&menu=004 UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile<!--Bot-generated title-->].</ref><ref>L. M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World 1995, Princeton University Press.</ref><ref>Jacques Bacid, Ph.D. Macedonia Through the Ages. Columbia University, 1983.</ref><ref>Hill, P. (1999) "Macedonians in Greece and Albania: A Comparative study of recent developments". Nationalities Papers Volume 27, 1 March 1999, p. 44(14).</ref><ref>Poulton, H.(2000), "Who are the Macedonians?",C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.</ref> Most of these people however do not have an ethnic Macedonian national consciousness, with many choosing to identify as ethnic [[Greeks]] or rejecting both ethnic designations. In 1999 the [[International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights|Greek Helsinki Monitor]] estimated that the number of people identifying as ethnic Macedonians numbered somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000.<ref>[http://dev.eurac.edu:8085/mugs2/do/blob.html?type=html&serial=1044526702223 Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Greece) - GREEK HELSINKI MONITOR (GHM)]</ref> In 1993, at the height of the name controversy and just before joining the [[UN]], the Macedonian government claimed that there were between 230,000 and 270,000 ethnic Macedonians living in northern Greece.{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} |

||

Since the 1980s there has been an ethnic Macedonian revival in Northern Greece. |

Since the 1980s there has been an ethnic Macedonian revival in Northern Greece.{{cn|date=August 2011}} Since then several{{cn|date=August 2011}} Macedonian language newspapers have been established, the most successful of which, Nova Zora, has a readership of over 20,000.{{cn|date=August 2011}} Several{{cn|date=August 2011}} ethnic Macedonian organisations including the [[Rainbow (political party)|Rainbow Party]] have been established. However, Rainbow hasn't participated in national elections since 2004 due to lack of funding.{{cn|date=August 2011}} Recently,{{when|date=August 2011}} several{{cn|date=August 2011}} ethnic Macedonian have been elected to local political positions{{cn|date=August 2011}} and the language has once again begun to be taught at an unofficial level across Northern Greece in [[Florina]], [[Thessaloniki]] and [[Edessa]].{{cn|date=August 2011}} |

||

====Serbia==== |

====Serbia==== |

||

{{Main|Macedonians in Serbia}} |

{{Main|Macedonians in Serbia}} |

||

Within [[Serbia]], Macedonians constitute an officially recognised ethnic at both a local and national level. Within [[ |

Within [[Serbia]], Macedonians constitute an officially recognised ethnic at both a local and national level. Within [[Vojovdina]] Macedonians are recognised under the [[Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina]], along with other ethnic groups. Large Macedonian settlements within Vojvodina can be found in [[Plandište]], [[Jabuka]], [[Glogonj]], [[Dužine]] and [[Kačarevo]]. These people are mainly the descendants of economic migrants who left the [[Socialist Republic of Macedonia]] in the 1950s and 1960s. The [[Macedonians in Serbia]] are represented by a national council and in recent years the Macedonian language has begun to be taught. The most recent census recorded 25,847 Macedonians living in Serbia.<ref>[http://webrzs.stat.gov.rs/zip/esn31.pdf 2002 Serbian Census]</ref> |

||

====Albania==== |

====Albania==== |

||

Revision as of 14:35, 23 August 2011

The Macedonians ([Македонци; transliterated: Makedonci] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help))– also referred to as Macedonian Slavs[36]– are a South Slavic people who are primarily associated with the Republic of Macedonia. They speak the Macedonian language, a South Slavic language. About two thirds of all ethnic Macedonians live in the Republic of Macedonia and there are also communities in a number of other countries.

Origins

The ancestry of present-day Macedonians is mixed: their linguistic and cultural origins stem largely from the 6th century CE migrations of various Slavic tribes to southeast Europe.[37] It is generally acknowledged that the ethnic Macedonian identity emerged in the late 19th century or even later.[38][39][40][41][42][43] However, the existence of a discernible Macedonian national consciousness prior to the 1940s is disputed.[44][45][46][47][48] Some early 20th century researchers as William Z. Ripley, Coon[49] and Bertil Lundman[50] and most late 19th and early 20th century ethnographers described the Slavic speakers in Macedonia as Bulgarians, and often placed both populations in a common racial subgroup.[51][52][53] Other authors, like historian Ferdinand Schevill and journalist H. N. Brailsford, described Slavic speakers from Macedonia as related to both Serbs and Bulgarians, but without clear defined ethnic consciousness.[54] Brailsford considered a part of the people of North West Macedonia as Serbs and the people of the region of Ohrid as Bulgarians.[55] The argument that the ethnic Macedonians are related with the Bulgarians is also advocated by some modern writers[56][57][58] and ethnic Macedonian politicians.[59]

The Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts accepts that as a whole the modern Macedonian genotype developed as a result of the absorption by the advancing Slavs of the local peoples living in the region of Macedonia prior to their coming. This position is based on the findings of some late 19th - early 20th centuries ethnographers such as Vasil Kanchov,[60] Gustav Weigand,[61] and the anthropologist Carleton S. Coon, which stated that the Slavs in 6th century actively assimilated other tribal peoples by absorbing part of the indigenous populations of the region of Macedonia, which was mainly combined by Greeks in the south and Thraco-Illyrian tribes in the north.[62] By absorbing parts of the peoples living there the Slavs also absorbed their culture, and in that amalgamation a people was gradually formed with predominantly Slavic ethnic elements, speaking a Slavonic language and with a Slavic-Byzantine culture. Furthermore, the genetic studies support the theories that Macedonians genetic heritage is derived from a mixture of ancient Balkan peoples[63] as well as the relatively newly arrived Slavs with deep European roots.

Population genetics studies using HLA loci have been used in light of unanswered questions regarding Macedonians' origins and relationship with other populations.[64] Macedonians are most closely related to other Balkanians as Croats, Serbs, Greeks, Romanians and especially Bulgarians.[33][65][66][67][68] It is also corroborated that there is some non-European inflow in modern Macedonians.[69]

Population

The vast majority of ethnic Macedonians live along the valley of the river Vardar, the central region of the Republic of Macedonia. They form about 64.18% of the population of the Republic of Macedonia (1,297,981 people according to the 2002 census). Smaller numbers live in eastern Albania, northern Greece, and southern Serbia, mostly abutting the border areas of the Republic of Macedonia. A large number of Macedonians have immigrated overseas to Australia, United States, Canada and in many European countries: Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Austria, among others.

Macedonians in the Balkans

| Part of a series on |

| Macedonians |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Macedonia (region) |

| Diaspora |

|

|

|

|

|

Subgroups and related groups |

|

|

| Culture |

|

|

| Religion |

| Other topics |

Greece

The existence of an ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece is rejected by the Greek government. The number of people speaking the Macedonian Slavic dialects has been estimated between 100,000 and 300,000.[70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78] Most of these people however do not have an ethnic Macedonian national consciousness, with many choosing to identify as ethnic Greeks or rejecting both ethnic designations. In 1999 the Greek Helsinki Monitor estimated that the number of people identifying as ethnic Macedonians numbered somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000.[79] In 1993, at the height of the name controversy and just before joining the UN, the Macedonian government claimed that there were between 230,000 and 270,000 ethnic Macedonians living in northern Greece.[citation needed]

Since the 1980s there has been an ethnic Macedonian revival in Northern Greece.[citation needed] Since then several[citation needed] Macedonian language newspapers have been established, the most successful of which, Nova Zora, has a readership of over 20,000.[citation needed] Several[citation needed] ethnic Macedonian organisations including the Rainbow Party have been established. However, Rainbow hasn't participated in national elections since 2004 due to lack of funding.[citation needed] Recently,[when?] several[citation needed] ethnic Macedonian have been elected to local political positions[citation needed] and the language has once again begun to be taught at an unofficial level across Northern Greece in Florina, Thessaloniki and Edessa.[citation needed]

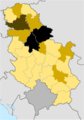

Serbia

Within Serbia, Macedonians constitute an officially recognised ethnic at both a local and national level. Within Vojovdina Macedonians are recognised under the Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, along with other ethnic groups. Large Macedonian settlements within Vojvodina can be found in Plandište, Jabuka, Glogonj, Dužine and Kačarevo. These people are mainly the descendants of economic migrants who left the Socialist Republic of Macedonia in the 1950s and 1960s. The Macedonians in Serbia are represented by a national council and in recent years the Macedonian language has begun to be taught. The most recent census recorded 25,847 Macedonians living in Serbia.[80]

Albania

Albania recognizes ethnic Macedonians as an ethnic minority and delivers primary education in the Macedonian language in the border regions where most ethnic Macedonians live. In the 1989 census, 4,697 people declared themselves ethnic Macedonians.[81] Ethnic Macedonian organizations allege that the government undercounts their number and that they are politically under-represented — there are no ethnic Macedonians in the Albanian parliament. Some say that there has been disagreement among the Slav-speaking Albanian citizens about their being members of a Macedonian nation as a significant percentage of their number are Torbeš and self-identify as Albanians. External estimates on the population of ethnic Macedonians in Albania include 10,000,[82] whereas ethnic Macedonian sources have claimed that there are 120,000 - 350,000 ethnic Macedonians in Albania.[citation needed]

Bulgaria

Bulgarians are considered most closely related to the neighboring Macedonians, indeed it is sometimes said there is no clear ethnic difference between them.[33] In the 2011 census in Bulgaria, 1,654 people declared themselves ethnic Macedonians (0,02%).[83] Krassimir Kanev, chairman of the non-governmental organization (NGO) Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, claimed 15,000 - 25,000 in 1998 (see here). In the same report Macedonian nationalists (Popov et al., 1989) claimed that 200,000 ethnic Macedonians live in Bulgaria. However, Bulgarian Helsinki Committee stated that the vast majority of the Slavic population in Pirin Macedonia has a Bulgarian national self-consciousness and a regional Macedonian identity similar to the Macedonian regional identity in Greek Macedonia. Finally, according to personal evaluation of a leading local ethnic Macedonian political activist, Stoyko Stoykov, the present number of Bulgarian citizens with ethnic Macedonian self-consciousness is between 5,000 and 10,000.[84] The Bulgarian Constitutional Court banned UMO Ilinden-Pirin, a small Macedonian political party, in 2000 as separatist and Bulgarian local authorities banned its political rallies. UMO Ilinden-Pirin claims that the minority has experienced a period of intensive assimilation and repression.[citation needed]

-

Macedonians in the Republic of Macedonia, according to the 2002 census

-

Citizens of the Republic of Macedonia in Greece as per the 2001 census

-

Concentration of Macedonians in Serbia (excluding Kosovo)

-

Regions where ethnic Macedonians live within Albania

The Macedonian Diaspora

Significant Macedonian communities can also be found in the traditional immigrant-receiving nations, as well as in Western European countries. It should be noted that census data in many European countries (such as Italy and Germany) does not take into account the ethnicity of émigrés from the Republic of Macedonia:

- Argentina: Most Macedonians can be found in Buenos Aires, the Pampas and Córdoba. An estimated 30,000 Macedonians can be found in Argentina.[5]

- Australia: The official number of Macedonians in Australia by birthplace or birthplace of parents is 83,893 (2001). The main Macedonian communities are found in Melbourne, Geelong, Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle, Canberra and Perth. (The 2006 Australian Census included a question of 'ancestry' which, according to Members of the Australian-Macedonian Community, this will result in a 'significant' increase of 'ethnic Macedonians' in Australia. However, the 2006 census recorded 83,983 people of Macedonian (ethnic) ancestry.) See also Macedonian Australians;

- Canada: The Canadian census in 2001 records 37,705 individuals claimed wholly or partly Macedonian heritage in Canada,[85] although community spokesmen have claimed that there are actually 100,000-150,000 Macedonians in Canada[86] (see also Macedonian Canadians);

- USA: A significant Macedonian community can be found in the United States of America. The official number of Macedonians in the USA is 49,455 (2004). The Macedonian community is located mainly in Michigan, New York, Ohio, Indiana and New Jersey[87] (See also Macedonian Americans);

- Germany: There are an estimated 61,000 citizens of the Republic of Macedonia in Germany (mostly in the Ruhrgebiet) (2001) (See also Ethnic Macedonians in Germany);

- Italy: There are 74, 162 citizens of the Republic of Macedonia in Italy (Foreign Citizens in Italy).

- Switzerland: In 2006 the Swiss Government recorded 60,362 Macedonian Citizens living in Switzerland. (See also Macedonians in Switzerland)[88]

- Romania: Ethnic Macedonians are an officially recognised minority group in Romania. They have a special reserved seat in the nations parliament. In 2002, they numbered 731. (see also Macedonians in Romania)

- Slovenia: Ethnic Macedonians began relocating to Slovenia in the 1950s when the two regions formed a part of a single country, Yugoslavia (see also Macedonians in Slovenia).

Other significant ethnic Macedonian communities can also be found in the other Western European countries such as Austria, France, Switzerland, Netherlands, United Kingdom, etc. Also in Uruguay, with a significant population in Montevideo.

Culture

The culture of the Macedonian people is characterized with both traditionalist and modernist attributes. It is strongly bound with their native land and the surrounding in which they live. The rich cultural heritage of the Macedonians is accented in the folklore, the picturesque traditional folk costumes, decorations and ornaments in city and village homes, the architecture, the monasteries and churches, iconostasis, wood-carving and so on. The culture of Macedonians can roughly be explained as a Balkanic, closely related to that of Serbs and Bulgarians.

Architecture

The typical Macedonian village house is presented as a construction with two floors, with a hard facade composed of large stones and a wide balcony on the second floor. In villages with predominantly agricultural economy, the first floor was often used as a storage for the harvest, while in some villages the first floor was used as a cattle-pen.

The stereotype for a traditional Macedonian city house is a two-floor building with white façade, with a forward extended second floor, and black wooden elements around the windows and on the edges.

Cinema and theater

The history of film making in the Republic of Macedonia dates back over 110 years. The first film to be produced on the territory of the present-day the country was made in 1895 by Janaki and Milton Manaki in Bitola. From then, continuing the present, Macedonian film makers, in Macedonia and from around the world, have been producing many films.

From 1993–1994 1,596 performances were held in the newly formed republic, and more than 330,000 people attended. The Macedonian National Theater (Drama, Opera and Ballet companies), the Drama Theater, the Theater of the Nationalities (Albanian and Turkish Drama companies) and the other theater companies comprise about 870 professional actors, singers, ballet dancers, directors, playwrights, set and costume designers, etc. There is also a professional theatre for children and three amateur theaters. For the last thirty years a traditional festival of Macedonian professional theaters has been taking place in Prilep in honor of Vojdan Černodrinski, the founder of the modern Macedonian theater. Each year a festival of amateur and experimental Macedonian theater companies is held in Kočani.

Music and art

Macedonian's music has an exceptionally rich musical heritage. Their music has many things in common with the music of neighboring Balkan countries, but maintains its own distinctive sound.

The founders of modern Macedonian painting included Lazar Licenovski, Nikola Martinoski, Dimitar Pandilov, and Vangel Kodzoman. They were succeeded by an exceptionally talented and fruitful generation, consisting of Borka Lazeski, Dimitar Kondovski, Petar Mazev who are now deceased, and Rodoljub Anastasov and many others who are still active. Others include: Vasko Taskovski and Vangel Naumovski. In addition to Dimo Todorovski, who is considered to be the founder of modern Macedonian sculpture, the works of Petar Hadzi Boskov, Boro Mitrikeski, Novak Dimitrovski and Tome Serafimovski are also outstanding.

Economy

In the past, the Macedonian population was predominantly involved with agriculture, with a very small portion of the people who were engaged in trade (mainly in the cities). But after the creation of the People's Republic of Macedonia which started a social transformation based on Socialist principles, a middle and heavy industry were started.

Language

The Macedonian language (македонски јазик) is a member of the Eastern group of South Slavic languages. Standard Macedonian was implemented as the official language of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia after being codified in the 1940s, and has accumulated a thriving literary tradition.

The closest relative of Macedonian is Bulgarian,[89] followed by Serbo-Croatian. All the South Slavic languages, including Macedonian, form a dialect continuum, in which Macedonian is situated between Bulgarian and Serbian. The Torlakian dialect group is intermediate between Bulgarian, Macedonian and Serbian, comprising some of the northernmost dialects of Macedonian as well as varieties spoken in southern Serbia.

The orthography of Macedonian includes an alphabet, which is an adaptation of the Cyrillic alphabet, as well as language-specific conventions of spelling and punctuation.

Religion

Most Macedonians are members of the Macedonian Orthodox Church. The official name of the church is Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric and is the body of Christians who are united under the Archbishop of Ohrid and Macedonia, exercising jurisdiction over Macedonian Orthodox Christians in the Republic of Macedonia and in exarchates in the Macedonian diaspora.

The church gained autonomy from the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1959 and declared the restoration of the historic Archbishopric of Ohrid. On July 19, 1967, the Macedonian Orthodox Church declared autocephaly from the Serbian church, a move which is not recognised by any of the churches of the Eastern Orthodox Communion, and since then, the Macedonian Orthodox Church is not in communion with any Orthodox Church.

Between the 15th and the 20th century, during the Ottoman rule, a large number of Orthodox Macedonian Slavs converted to Islam. Today in the Republic of Macedonia they are regarded as Macedonian Muslims. A small number of Macedonians belong to the Protestant and the Roman Catholic churches.

.

Names

Cuisine

Macedonian cuisine is a representative of the cuisine of the Balkans—reflecting Mediterranean (Greek and Turkish) and Middle Eastern influences, and to a lesser extent Italian, German and Eastern European (especially Hungarian) ones. The relatively warm climate in Macedonia provides excellent growth conditions for a variety of vegetables, herbs and fruits. Thus, Macedonian cuisine is particularly diverse.

Famous for its rich Shopska salad, an appetizer and side dish which accompanies almost every meal, Macedonian cuisine is also noted for the diversity and quality of its dairy products, wines, and local alcoholic beverages, such as rakija. Tavče Gravče and mastika are considered the national dish and drink of the Republic of Macedonia, respectively.

Identities

- See also: Macedonian Question and Macedonian nationalism

Macedonians are people with a unique identity derived from an influence of different cultures. The large majority identify themselves as Orthodox Christians, who speak a Slavic language, and share similarities in culture with their Balkan neighbours. The concept of a distinct "Macedonian" ethnicity is seen as a relatively new arrival to the milieu of peoples that is the Balkans. Throughout the Middle Ages and until the early 20th century, there was no clear formulation or expression of a distinct and unified Macedonian ethnicity, although distinct Slavic tribes had existed in Macedonia since the 7th century, and some dialectical differences existed between the eastern-South Slavic developed in Medieval Ohrid vis-a-vis that in Preslav. Nevertheless, the Slavic speaking majority in the Region of Macedonia had been referred to (both, by themselves and outsiders) as Bulgarians, and that is how they were predominantly seen since 10th,[90][91][92] up until the early 20th century.[47][48][93] However, in these pre-nationalist times, terms such as "Bulgarian" did not necessarily posses a strict ethno-nationalistic meaning, rather, they were loose, often interchangeable terms which could simultaneously denote regional habitation, alliegence to a particular empire, religious orientation, and even membership in certain social groups.[94][95][96][97] Ever since its independence movement began in late 19th century, Macedonia had been trying to get free from Turkish rule, either as an independent state or as part of Bulgaria proper.[98] During this period, the first expressions of ethnic nationalism by certain Macedonian intellectuals occurred in Belgrade, Sofia, Istanbul, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg. The activities of these people was registered by Petko Slaveykov[99] and Stojan Novaković[100]

The first prominent author that propagated the separate ethnicity of the Macedonians was Georgi Pulevski, who in 1875 published Dictionary of Three languages: Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish, in which he wrote:

"What do we call a nation"? "People who are of the same origin and who speak the same words and who live and make friends of each other, who have the same customs and songs and entertainment are what we call a nation, and the place where that people lives is called the people's country. Thus the Macedonians also are a nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia."

On the other hand Theodosius of Skopje, a priest who have hold a high ranking positions within the Bulgarian Exarchate was chosen as a bishop of the episcopacy of Skopje in 1885. As a bishop of Skopje, Theodosius renounced de facto the Bulgarian Exarchate and attempted to restore the Archbishopric of Ohrid and to separate the episcopacies in Macedonia from the Exarchate.[101] During this time period Metropolitan Bishop Theodosius of Skopje made several pleas to the Bulgarian church to allow a separate Macedonian church, he viewed this as the only way to end the turmoil in the Balkans.

In 1903 Krste Petkov Misirkov published his book On Macedonian Matters in which he laid down the principles of the modern Macedonian nationhood and language. This book is considered by ethnic Macedonians as a milestone of the ethnic Macedonian identity and the apogee of the process of Macedonian awakening.[citation needed] In his article "Macedonian Nationalism" he wrote:

I hope it will not be held against me that I, as a Macedonian, place the interests of my country before all... I am a Macedonian, I have a Macedonian's consciousness, and so I have my own Macedonian view of the past, present, and future of my country and of all the South Slavs; and so I should like them to consult us, the Macedonians, about all the questions concerning us and our neighbours, and not have everything end merely with agreements between Bulgaria and Serbia about us – but without us.

The next great figure of the Macedonian awakening was Dimitrija Čupovski, one of the founders of the Macedonian Literary Society, established in Saint Petersburg in 1902. In the period 1913–1918, Čupovski published the newspaper Македонскi Голосъ (Macedonian Voice) in which he and fellow members of the Petersburg Macedonian Colony propagated the existence of a Macedonian people separate from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, and sought to popularize the idea for an independent Macedonian state.

After the Balkan Wars, following division of the region of Macedonia amongst the Kingdom of Greece, the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Kingdom of Serbia, and after World War I, the idea of belonging to a separate Macedonian nation was further spread among the Slavic-speaking population. The suffering during the wars, the endless struggle of the Balkan monarchies for dominance over the population increased the Macedonians' sentiment that the institutionalization of an independent Macedonian nation would put an end to their suffering. On the question of whether they were Serbs or Bulgarians, the people more often started answering: "Neither Bulgar, nor Serb... I am Macedonian only, and I'm sick of war."[102][103]

The first political organization that promoted the existence of a separate ethnic Macedonian nation was Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (United),[104] composed of former left-wing Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) members and founded in 1925. This idea was internationalized and backed by the Comintern which issued in 1934 a resolution supporting the development of the entity.[105] This action was attacked by the IMRO, but was supported by the Balkan communists. The Balkan communist parties supported the national consolidation of the ethnic Macedonian people and created Macedonian sections within the parties, headed by prominent IMRO (United) members. The sense of belonging to a separate Macedonian nation gained credence during World War II when ethnic Macedonian partisan detachments were formed, and especially after World War II when ethnic Macedonian institutions were created in the three parts of the region of Macedonia,[106] including the establishment of the People's Republic of Macedonia within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRJ).

History

The history of the ethnic Macedonians is closely associated with the historical and geographical region of Macedonia, and is manifested with their constant struggle for an independent state. After many decades of insurrections and living through several wars, the Macedonians in World War II managed to create their own country.

Symbols

|

|

- Sun: The official flag of the Republic of Macedonia, adopted in 1995, is a yellow sun with eight broadening rays extending to the edges of the red field.

- Coat of Arms: After independence in 1992, the Republic of Macedonia retained the coat of arms adopted in 1946 by the People's Assembly of the People's Republic of Macedonia on its second extraordinary session held on July 27, 1946, later on altered by article 8 of the Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Macedonia. The coat-of-arms is composed by a double bent garland of ears of wheat, tobacco and poppy, tied by a ribbon with the embroidery of a traditional folk costume. In the center of such a circular room there are mountains, rivers, lakes and the sun. All this is said to represent "the richness of our country, our struggle, and our freedom".

Unofficial symbols

- Lion: The lion first appears in the Fojnica Armory from 1340,[107] where the coat of arms of Macedonia is included among with those of other countries. On the coat of arms is a crown, inside a yellow crowned lion is depicted standing rampant, on a red background. On the bottom enclosed in a red and yellow border is written "Macedonia". The use of the lion to represent Macedonia was continued in foreign heraldic collections throughout the 15th to 18th centuries.[108][109] Modern versions of the historical lion has also been added to the emblem of several political parties, organizations and sports clubs.

- Vergina Sun: (official flag, 1992–1995) The Vergina Sun is used by various associations and cultural groups in the Macedonian diaspora. The Vergina Sun is believed to have been associated with ancient Greek kings such as Alexander the Great and Philip II, although it was used as an ornamental design long before the Macedonian period. The symbol was discovered in the present-day Greek region of Macedonia and Greeks regard it as a misappropriation of a Hellenic symbol, unrelated to Slavic cultures, and a direct claim on the legacy of Philip II. Greece had the Vergina Sun copyrighted under WIPO as a State Emblem of Greece in the 1990s.[110] The Vergina sun on a red field was the first flag of the independent Republic of Macedonia, until it was removed from the state flag under an agreement reached between the Republic of Macedonia and Greece in September 1995.[111] The Vergina sun is still used[112] unofficially as a national symbol by some groups in the country and Macedonian diaspora.

Macedonians through history

-

Georgi Pulevski,[1] the first author that separated the Macedonian nation from the others.

-

Theodosius of Skopje,[1] the first priest who attempted to create a separate Macedonian Church.

-

Goce Delchev,[113] IMARO revolutionary, considered a native national hero in both Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia.

-

Krste Petkov Misirkov,[1] a philologist who first outlined the principles of the Macedonian language.

-

Dimitrija Čupovski, Macedonian textbook writer and lexicographer

-

Čede Filipovski Dame, Macedonian partisan (On the picture: Memorial to Dame in Gostivar, Macedonia).

-

Milčo Mančevski, film director and screen writer.

-

Ed Jovanovski, National Hockey League player.

-

Blagoj Nacoski, tenor opera singer.

-

Darko Dimitrov, composer.

-

Karolina Gočeva, singer.

-

Kiril Lazarov, handball player.

-

Goran Pandev, football striker.

-

Toše Proeski, singer and humanitarian.

-

Kaliopi, singer and songwriter.

-

Katarina Ivanovska, international model.

-

Elena Risteska, singer and songwriter.

See also

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- List of Macedonians

- Demographics of the Republic of Macedonia

- Macedonian language

- Ethnogenesis

- South Slavs

References

- ^ a b c d e People that are considered to be Bulgarians in Bulgaria and Macedonians in the Republic of Macedonia.

- ^ a b c Nasevski, Boško (1995). Македонски Иселенички Алманах '95. Skopje: Матица на Иселениците на Македонија. pp. 52 & 53.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ 2002 census.

- ^ 2006 Census.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Population Estimate from the MFA. Cite error: The named reference "autogenerated1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Foreign Citizens in Italy, 2009.

- ^ 2006 figures.

- ^ 2005 Figures.

- ^ 2009 Community Survey.

- ^ Mac. Information Agency

- ^ 2006 census.

- ^ 2001 census.

- ^ 2002 census.

- ^ 2001 census - Tabelle 13: Ausländer nach Staatsangehörigkeit (ausgewählte Staaten), Altersgruppen und Geschlecht — p. 74.

- ^ a b 1996 Estimate.

- ^ http://www.fes.hr/E-books/pdf/Local%20Self%20Government/09.pdf Artan Hoxha and Alma Gurraj "LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT AND DECENTRALIZATION: CASE OF ALBANIA. HISTORY, REFORMES AND CHALLENGES" "...According to latest Albanian census conducted in April 1989, 98% of Albanian population are Albanian ethnic. The remaining 2% (or 64816 people) belong to ethnic minorities: the vast majority is composed by ethnic Greeks (58758 ); ethnic Macedonians (4697)...",[1], Joshua Project.

- ^ OECD Statistics.

- ^ 2002 census.

- ^ 2002 census.

- ^ 2006 census.

- ^ "Belgium population statistics". www.dofi.fgov.be. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ 2008 census.

- ^ 2008 figures.

- ^ 2003 census,Population Estimate from the MFA.

- ^ 2005 census.

- ^ a b Makedonci vo Svetot.

- ^ Polands Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947, p. 260.

- ^ 1.Bulgarian census data.

- ^ Montenegrin 2011 census -.

- ^ "Πίνακας 7: Αλλοδαποί κατά υπηκοότητα, φύλο και επίπεδο εκπαίδευσης - Σύνολο Ελλάδας και Νομοί" (PDF). Greek National Statistics Agency. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Greece – Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (along guidelines for state reports according to Article 25.1 of the Convention)". Greek Helsinki Monitor (GHM) & Minority Rights Group – Greece (MRG-G). 1999-09-18. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ 2002 census.

- ^ a b c Political and economic dictionary of Eastern Europe, Alan John Day, Roger East, Richard Thomas, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 1857430638, p. 96.

- ^ "Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States", p. 517 The Macedonians are a Southern Slav people, closely related to Bulgarians.

- ^ "Ethnic groups worldwide: a ready reference handbook", p. 54 Macedonians are a Slavic people closely related to the neighboring Bulgarians.

- ^ "Macedonian Slavs" can be translated into Macedonian as Македонски Словени (Makedonski Sloveni). "Slavs" is the primary qualifier used by scholars in order to disambiguate the ethnic Macedonians from all other Macedonians in the region (see Google scholar for instance). Krste Misirkov himself used the same qualifier numerous times in one of the first ethnic Macedonian patriotic texts "On Macedonian Matters" (most of the text in English here). The Slav Macedonians in Greece were happy to be acknowledged as "Slavomacedonians". A native of Greek Macedonia, a pioneer of Slav Macedonian schools in the region and a local historian, Pavlos Koufis, wrote in Laografika Florinas kai Kastorias (Folklore of Florina and Kastoria), Athens 1996, that (translation by User:Politis),

"[During its Panhellenic Meeting in September 1942, the KKE mentioned that it recognises the equality of the ethnic minorities in Greece] the KKE recognised that the Slavophone population was ethnic minority of Slavomacedonians]. This was a term, which the inhabitants of the region accepted with relief. [Because] Slavomacedonians = Slavs+Macedonians. The first section of the term determined their origin and classified them in the great family of the Slav peoples."

However, the current use of "Slavomacedonian" in reference to both the ethnic group and the language, although acceptable in the past, can be considered pejorative and offensive by some ethnic Macedonians living in Greece. The Greek Helsinki Monitor reports:

: "... the term Slavomacedonian was introduced and was accepted by the community itself, which at the time had a much more widespread non-Greek Macedonian ethnic consciousness. Unfortunately, according to members of the community, this term was later used by the Greek authorities in a pejorative, discriminatory way; hence the reluctance if not hostility of modern-day Macedonians of Greece (i.e. people with a Macedonian national identity) to accept it." - ^ Karen Dawisha, Bruce Parrott, Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe (Democratization and Authoritarianism in Post-Communist Societies), Cambridge University Press, 1997: "A Slavic-speaking people, todays ethnic Macedonians, are descendants of Slavs who settled in the Balkans during the seventh century AD".

- ^ Krste Misirkov, On the Macedonian Matters (Za Makedonckite Raboti), Sofia, 1903: "And, anyway, what sort of new Macedonian nation can this be when we and our fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers have always been called Bulgarians?"

- ^ Sperling, James; Kay, Sean; Papacosma, S. Victor (2003). Limiting institutions?: the challenge of Eurasian security governance. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7190-6605-4.

Macedonian nationalism Is a new phenomenon. In the early twentieth century, there was no separate Slavic Macedonian identity

- ^ Titchener, Frances B.; Moorton, Richard F. (1999). The eye expanded: life and the arts in Greco-Roman antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-520-21029-5.

On the other hand, the Macedonians are a newly emergent people in search of a past to help legitimize their precarious present as they attempt to establish their singular identity in a Slavic world dominated historically by Serbs and Bulgarians. ... The twentieth-century development of a Macedonian ethnicity, and its recent evolution into independent statehood following the collapse of the Yugoslav state in 1991, has followed a rocky road. In order to survive the vicissitudes of Balkan history and politics, the Macedonians, who have had no history, need one.

- ^ Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-8014-8736-6.

The key fact about Macedonian nationalism is that it is new: in the early twentieth century, Macedonian villagers defined their identity religiously—they were either "Bulgarian," "Serbian," or "Greek" depending on the affiliation of the village priest. ... According to the new Macedonian mythology, modern Macedonians are the direct descendants of Alexander the Great's subjects. They trace their cultural identity to the ninth-century Saints Cyril and Methodius, who converted the Slavs to Christianity and invented the first Slavic alphabet, and whose disciples maintained a centre of Christian learning in western Macedonia. A more modern national hero is Gotse Delchev, leader of the turn-of-the-century Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which was actually a largely pro-Bulgarian organization but is claimed as the founding Macedonian national movement.

- ^ Rae, Heather (2002). State identities and the homogenisation of peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0-521-79708-X.

Despite the recent development of Macedonian identity, as Loring Danforth notes, it is no more or less artificial than any other identity. It merely has a more recent ethnogenesis - one that can therefore more easily be traced through the recent historical record.

- ^ Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6.

Unlike the Slovene and Croatian identities, which existed independently for a long period before the emergence of SFRY Macedonian identity and language were themselves a product federal Yugoslavia, and took shape only after 1944. Again unlike Slovenia and Croatia, the very existence of a separate Macedonian identity was questioned—albeit to a different degree—by both the governments and the public of all the neighboring nations (Greece being the most intransigent)

- ^ Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, 1995, Princeton University Press, p.65, ISBN 0691043566

- ^ Stephen Palmer, Robert King, Yugoslav Communism and the Macedonian question,Hamden, Connecticut Archon Books, 1971, p.p.199-200

- ^ The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939-1949, Dimitris Livanios, edition: Oxford University Press, US, 2008, ISBN 0199237689, p. 65.

- ^ a b The struggle for Greece, 1941-1949, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1850654921, p. 67.

- ^ a b Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton,Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1995, ISBN 1850652384, 9781850652380, p. 101.

- ^ in his book The Races Of Europe.

- ^ Lundman, Bertil J. - The Races and Peoples of Europe (New York: IAAEE. 1977)[2].

- ^ Cousinéry, Esprit Marie. Voyage dans la Macédoine: contenant des recherches sur l'histoire, la géographie, les antiquités de ce pay, Paris, 1831, Vol. II, p. 15-17, one of the passages in English – [3], Engin Deniz Tanir, The Mid-Nineteenth century Ottoman Bulgaria from the viewpoints of the French Travelers, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University, 2005, p. 99, 142

- ^ Pulcherius, Receuil des historiens des Croisades. Historiens orientaux. III, p. 331 – a passage in English -http://promacedonia.org/en/ban/nr1.html#4

- ^ Kuzman Shapkarev, in a letter to Professor Marin Drinov of May 25, 1888, Makedonski pregled, IX, 2, 1934, p. 55; (the original letter is kept in the Marin Drinov Museum in Sofia, and it is available for examination and study): "But even stranger is the name 'Macedonians', which was imposed on us only 10 to 15 years ago by outsiders and not as something by our own intellectuals... Yet the people in Macedonia know nothing of that ancient name, reintroduced today with a cunning aim on the one hand and a stupid one on the other. They know the older word: 'Bugari', although mispronounced: they have even adopted it as peculiarly theirs, inapplicable to other Bulgarians. You can find more about this in the introduction to the booklets I am sending you. They call their own Macedono-Bulgarian dialect the 'Bugarski language', while the rest of the Bulgarian dialects they refer to as the 'Shopski language'."

- ^ Ferdinand Schevill, American professor of history, History of the Balkans: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, 1922, reprint 1991, Marboro Books : "Although in some areas (i.e. of the region of Macedonia) the various groups were all inextricably intermingled, it is pertinent to point out that in other sections a given race decidedly predominated. In the southern districts, for instance, and more particularly along the coast, the Greeks, a city people given to trade, had the upper hand, while to the north of them the Slavs, peasants for the most part working the soil, held sway. These Slavs may properly be considered as a special 'Macedonian' group, but since they were closely related to both Bulgars and Serbs and had, moreover, in the past been usually incorporated in either the Bulgar or Serb state, they inevitably became the object of both Bulgar and Serb aspirations and an apple of discord between these rival nationalities. As an oppressed people on an exceedingly primitive level, the Macedonian Slavs had as late as the congress of Berlin exhibited no perceptible national consciousness of their own. It was therefore impossible to foretell in what direction they would lean when their awakening came; in fact, so indeterminate was the situation that under favourable circumstances they might even develop their own particular Macedonian consciousness."

- ^ MACEDONIA: Its races and their future. H. N. Brailsford, London, 1906. p. 101.

- ^ Elizabeth Barker, Macedonia, Its Place in Balkan Power Politics, Royal Institute of International Affairs, London, 1950, pp19-20, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1980, p.10: "It is the national identity of these Slav Macedonians that has been the most violently contested aspect of the whole Macedonian dispute, and is still being contested today. There is no doubt that they are southern Slavs; they have a language, or a group of varying dialects, that is grammatically akin to Bulgarian but phonetically in some respects akin to Serbian, and which has certain quite distinctive features of its own...In regard to their own national feelings, all that can safely be said is that during the last eighty years many more Slav Macedonians seem to have considered themselves Bulgarian, or closely linked to Bulgaria, than have considered themselves Serbian, or closely linked to Serbia (or Yugoslavia). Only the people of the Skopje region, in the North West, have ever shown much tendency to regard themselves as Serbs. The feeling of being Macedonians and nothing but Macedonians, seems to be a sentiment of fairly recent growth, and even today is not very deep-rooted."

- ^ Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Chapter 9: The Encouragement of Macedonian Culture, Archon Books, 1971: "The treatment of Macedonian history has the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonians and create a separate national consciousness."

- ^ Thomas Gerard Gallagher, Outcast Europe, Routledge, 2001, p.47: "Where an overarching identity existed among Slavs in Macedonia, it was a Bulgarian one until at least the 1860s. The cultural impetus for a separated 'Macedonian identity' would only emerge later."

- ^ Ljubčo Georgievski, former Prime Minister and Vice President of the Republic of Macedonia, in his book С лице към истината (Facing the truth), Standart News, Ljubčo Georgievski seeks the spirit of Gotse Delchev (in Bulgarian), retrieved 2007-08-29: "Why are we ashamed and flee from the truth that whole positive Macedonian revolutionary tradition comes exactly from exarchist part of Macedonian people. We shall not say a new truth if we mention the fact that everyone, Gotse Delchev, Dame Gruev, Gjorche Petrov, Pere Toshev - must I list and count all of them — were teachers of the Bulgarian Exarchate in Macedonia."

- ^ Пътуване по долините на Струма, Места и Брегалница. Битолско, Преспа и Охридско. Васил Кънчов (Избрани произведения. Том I. Издателство "Наука и изкуство", София 1970) [4].

- ^ (ETHNOGRAPHIE VON MAKEDONIEN, Geschichtlich-nationaler, spraechlich-statistischer Teil von Prof. Dr. Gustav Weigand, Leipzig, Friedrich Brandstetter, 1924, Превод Елена Пипилева)[5].

- ^ "Macedonia: History". Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ Rebala K et al. (2007), Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin, Journal of Human Genetics, 52:406-14.

- ^ Petlichkovski A, Efinska-Mladenovska O, Trajkov D, Arsov T, Strezova A, Spiroski M (2004). "High-resolution typing of HLA-DRB1 locus in the Macedonian population". Tissue Antigens. 64 (4): 486–91. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00273.x. PMID 15361127.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ivanova M, Rozemuller E, Tyufekchiev N, Michailova A, Tilanus M, Naumova E (2002). "HLA polymorphism in Bulgarians defined by high-resolution typing methods in comparison with other populations". Tissue Antigens. 60 (6): 496–504. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600605.x. PMID 12542743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bulgarian Bone Marrow Donors Registry—past and future directions — Asen Zlatev, Milena Ivanova, Snejina Michailova, Anastasia Mihaylova and Elissaveta Naumova, Central Laboratory of Clinical Immunology, University Hospital "Alexandrovska", Sofia, Bulgaria, Published online: 2 June 2007 [6].

- ^ "European Journal of Human Genetics - Y chromosomal heritage of Croatian population and its island isolates".

- ^ Semino, Ornella; Passarino, G; Oefner, PJ; Lin, AA; Arbuzova, S; Beckman, LE; De Benedictis, G; Francalacci, P; Kouvatsi, A (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective" (PDF). Science. 290 (5494): 1155–59. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

- ^ HLA-DRB and -DQB1 polymorphism in the Macedonian population, Hristova-Dimceva et al., Tissue Antigens, Volume 55, Number 1, January 2000 , pp. 53-56(4), Publisher: Wiley-Blackwell

- ^ Bulgaria and Europe: Shifting Identities, East European and Eurasian Studies, Author Stefanos Katsikas, Publisher Anthem Press, 2010, ISBN 1843318466, p. 234.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Greece". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/new-multimedia/pdf/wordat077.pdf

- ^ UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile.

- ^ UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile.

- ^ L. M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World 1995, Princeton University Press.

- ^ Jacques Bacid, Ph.D. Macedonia Through the Ages. Columbia University, 1983.

- ^ Hill, P. (1999) "Macedonians in Greece and Albania: A Comparative study of recent developments". Nationalities Papers Volume 27, 1 March 1999, p. 44(14).

- ^ Poulton, H.(2000), "Who are the Macedonians?",C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

- ^ Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Greece) - GREEK HELSINKI MONITOR (GHM)

- ^ 2002 Serbian Census

- ^ Artan Hoxha and Alma Gurraj, Local Self-Government and Decentralization: Case of Albania. History, Reforms and Challenges. In: Local Self Government and Decentralization in South — East Europe. Proceedings of the workshop held in Zagreb, Croatia 6 April 2001. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Zagreb Office, Zagreb 2001, pp. 194-224 [7].

- ^ "Landesinformationen: AlbINFO by albanien.ch". www.albanien.ch. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ "Bulgarian 2011 census" (PDF). www.nsi.bg. Retrieved 2011-07-21.

- ^ "FOCUS Information Agency". www.focus-fen.net. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTTable?_bm=y&-state=dt&-context=dt&-reg=DEC_2000_SF4_U_PCT001:001%7C547;&-ds_name=ACS_2004_EST_G00_&-TABLE_NAMEX=&-ci_type=A&-mt_name=ACS_2004_EST_G2000_B04003&-CONTEXT=dt&-tree_id=4001&-all_geo_types=N&-redoLog=true&-geo_id=01000US&-search_results=01000US&-format=&-_lang=en

- ^ http://www.canadianencyclopedia.ca/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1SEC823709

- ^ http://www.euroamericans.net/euroamericans.net/macedonian.htm

- ^ http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/fr/index/themen/01/07/blank/key/01/01.Document.20578.xls

- ^ Levinson & O'Leary (1992:239)

- ^ Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1850655340, p. 19-20.

- ^ Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македонија, Иван Микулчиќ, Македонска академија на науките и уметностите — Скопје, 1996, стр. 72.

- ^ Formation of the Bulgarian nation: its development in the Middle Ages (9th-14th c.) Academician Dimitŭr Simeonov Angelov, Summary, Sofia-Press, 1978, pp. 413-415.

- ^ Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe, Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE) - "Macedonians of Bulgaria", p. 14.

- ^ When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans. J V A Fine. Pg 3-5

- ^ Relexification Hypothesis in Rumanian. Paul Wexler. Pg 170

- ^ Cumans and Tartars: Oriental military in the pre-Ottoman Balkans. Istvan Vasary. Pg 18

- ^ Byzantium's Balkan Frontier. Paul Stephenson. Pg 78-79

- ^ The Bulgarian Jews and the Final Solution, 1940-1944, Frederick B. Chary, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1972, ISBN 0822984431, p. 45.

- ^ "The Macedonian question" published 18 January 1871.

- ^ Балканска питања и мање историјско-политичке белешке о Балканском полуострву 1886–1905. Стојан Новаковић, Београд, 1906.

- ^ Theodosius of Skopje Centralen D'rzhaven istoricheski archiv (Sofia) 176, op. 1. arh.ed. 595, l.5-42 - Razgledi, X/8 (1968), pp. 996-1000.

- ^ Историја на македонската нација. Блаже Ристовски, 1999, Скопје.

- ^ "On the Monastir Road". Herbert Corey, National Geographic, May 1917 (p. 388.)

- ^ The Situation in Macedonia and the Tasks of IMRO (United) - published in the official newspaper of IMRO (United), "Македонско дело", N.185, April 1934.

- ^ Резолюция о македонской нации (принятой Балканском секретариате Коминтерна — Февраль 1934 г, Москва.

- ^ History of the Balkans, Vol. 2: Twentieth Century. Barbara Jelavich, 1983.

- ^ Fojnica Armory, online images.

- ^ Matkovski, Aleksandar, Grbovite na Makedonija, Skopje, 1970.

- ^ Александар Матковски (1990) Грбовите на Македонија, Мисла, Skopje, Macedonia — ISBN 86-15-00160-X

- ^ http://www.wipo.int/cgi-6te/guest/ifetch5?ENG+6TER+15+1151315-REVERSE+0+0+1055+F+125+431+101+25+SEP-0/HITNUM,B+KIND%2fEmblem+

- ^ Floudas, Demetrius Andreas; ""A Name for a Conflict or a Conflict for a Name? An Analysis of Greece's Dispute with FYROM",". 24 (1996) Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 285. 1996. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ http://heraldry.mol.com.mk/macedonian_symbols.htm

- ^ The Bulgarian ethnic self-identification of Delchev has been recognized from leading international researchers of the Macedonian Question. Delchev, openly said that “We are Bulgarians”(Mac Dermott, 1978:192, 273, quoted in Danforth, 1995:64) and addressed “the Slavs of Macedonia as ‘Bulgarians’ in an offhanded manner without seeming to indicate that such a designation was a point of contention” (Perry, 1988:23, quoted in Danforth, 1995:64). See: Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe - Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE), Slavic-Macedonians of Bulgaria, p. 5.

Further reading

- Brown, Keith, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004). "Fertility, families and ethnic conflict: Macedonians and Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia, 1944–2002". Nationalities Papers. 32 (3): 565–598. doi:10.1080/0090599042000246406.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cowan, Jane K. (ed.), Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference, Pluto Press, 2000. A collection of articles.

- Danforth, Loring M., The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-691-04356-6.

- Karakasidou, Anastasia N., Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870–1990, University Of Chicago Press, 1997, ISBN 0-226-42494-4. Reviewed in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 18:2 (2000), p465.

- Mackridge, Peter, Eleni Yannakakis (eds.), Ourselves and Others: The Development of a Greek Macedonian Cultural Identity since 1912, Berg Publishers, 1997, ISBN 1-85973-138-4.

- Poulton, Hugh, Who Are the Macedonians?, Indiana University Press, 2nd ed., 2000. ISBN 0-253-21359-2.

- Roudometof, Victor, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Praeger Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-275-97648-3.

- Κωστόπουλος, Τάσος, Η απαγορευμένη γλώσσα: Η κρατική καταστολή των σλαβικών διαλέκτων στην ελληνική Μακεδονία σε όλη τη διάρκεια του 20ού αιώνα (εκδ. Μαύρη Λίστα, Αθήνα 2000). [Tasos Kostopoulos, The forbidden language: state suppression of the Slavic dialects in Greek Macedonia through the 20th century, Athens: Black List, 2000]

External links

- New Balkan Politics - Journal of Politics

- Macedonians in the UK

- United Macedonian Diaspora

- World Macedonian Congress

- House Of Immigrants

![Unofficial Coat of Arms [citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/8/87/RoM_unofficial_coat_of_arms.svg/93px-RoM_unofficial_coat_of_arms.svg.png)

![Georgi Pulevski,[1] the first author that separated the Macedonian nation from the others.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Georgi_Pulevski.jpg/85px-Georgi_Pulevski.jpg)

![Theodosius of Skopje,[1] the first priest who attempted to create a separate Macedonian Church.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/9/9a/Teodisij_gologanov.jpg/86px-Teodisij_gologanov.jpg)

![Goce Delchev,[113] IMARO revolutionary, considered a native national hero in both Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/G_Delchev.jpg/82px-G_Delchev.jpg)

![Krste Petkov Misirkov,[1] a philologist who first outlined the principles of the Macedonian language.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/Krste_P._Misirkov.jpg/83px-Krste_P._Misirkov.jpg)