Piracy in the Sulu and Celebes Seas

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Sulu and Celebes Seas, a semi-enclosed sea area and porous region that covers an area of space around 1 million square kilometres,[1] have been subject to illegal maritime activities since the pre-colonial era[2] and continue to pose a maritime security threat to bordering nations up to this day. While piracy has long been identified as an ubiquitous challenge, being historically interwoven with the region,[3] recent incidents also include other types of maritime crimes such as kidnapping and the trafficking of humans, arms and drugs. Attacks mostly classify as 'armed robbery against ships' according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as they occur in maritime zones that lie under the sovereignty of a coastal state.[4] Incidents in the Sulu and Celebes Seas specifically involve the abduction of crew members. Since March 2016, the Information Sharing Centre (ISC) of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) reports a total of 86 abuctions,[5] leading to the issue of a warning for ships transpassing the area.[6]

History of piracy in the region

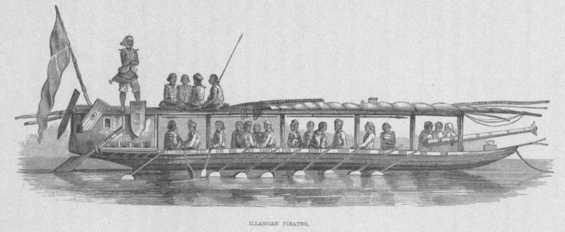

Piracy in the Sulu and Celebes Seas has a long history of attacks and raids, with the region being influenced primarily by raiders from the Sulu Sea who originated in the southern parts of the Philippines. The Sulu raiders were mostly composed of the Ilanun (or Iranun) and the Sama group of sea nomads as well as the influential Tausug aristocrates from Jolo Island.[7] Historically piracy occurred in and around the vicinity of the Sulu island Mindanao, where frequent acts of piracy were committed against the Spanish. These attacks of the local population are often known as the Spanish-Moro conflict. The term "Moro" thereby originated in the Spanish description as they introduced the derogatory term for Muslims and portrayed them in negative terms primarily due to their opposition to Spanish colonial rule and Christianity.[8] However, the term is being reclaimed by ethnic Filipinos today [according to whom?] and constitutes a re-claiming of Muslim identity, which is why the term will be used in the present article as well.

Because of the continual wars between Spain and the Moro people, the areas in and around the Sulu Sea saw re-occurring incidents of piracy attacks, which were not suppressed until the beginning of the 20th century. The pirates of that period should not be confused with the naval forces or privateers of the various Moro tribes. However, many of the pirates operated under government sanction during time of war.[9][10]: 383–397

The Moro Pirates and Spanish colonial occupation

Moro piracy is often linked to the Spanish colonial occupation of the Philippines. In a course of over two and a half centuries, Moro piratical attacks on Christian communities caused "an epoch of wholesale misery for the inhabitants".[11] After the Spanish arrival in 1521, Moro piratical raids against Christian settlements started in June 1578. These spread all over the archipelago and were conducted with impunity by organized fleets carrying weapons of destruction almost equal to those of the Spaniards.[11] The re-curring act is often described as a reaction against the Spaniards, who had displaced the Moros from the political and economic dominance they once enjoyed in the region (e.g. strategic commercial standpoints in Mindanano).[11] Moreover, religious differences between Muslims and Christians are frequently cited.

The Spanish engaged the Moro pirates frequently in the 1840s. The expedition to Balanguingui in 1848 was commanded by Brigadier José Ruiz with a fleet of nineteen small warships and hundreds of Spanish Army troops. They were opposed by at least 1,000 Moros holed up in four forts with 124 cannons and plenty of small arms. There were also dozens of proas at Balanguingui but the pirates abandoned their ships for the better defended fortifications. The Spanish stormed three of the positions by force and captured the remaining one after the pirates had retreated. Over 500 prisoners were freed in the operation and over 500 Moros were killed or wounded, they also lost about 150 proas. The Spanish lost twenty-two men killed and around 210 wounded. The pirates later reoccupied the island in 1849. Another expedition was sent which encountered only light resistance.[citation needed]

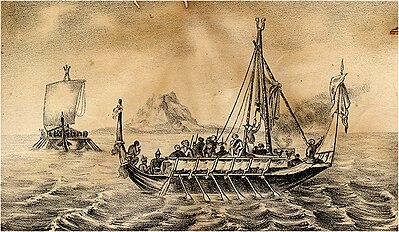

In the 1840s, James Brooke became the White Rajah of Sarawak and led a series of campaigns against the Moro pirates. In 1843 Brooke attacked the pirates of Malludu and in June 1847 he participated in a major battle with pirates at Balanini where dozens of proas were captured or sunk. Brooke fought in several more anti-piracy actions in 1849 as well. During one engagement off Mukah with Illanun Sulus in 1862, his nephew, ex-army Captain Brooke, sank four proas, out of six engaged, by ramming them with his small four-gun steamship Rainbow. Each pirate ship had over 100 crewmen and galley slaves aboard and was armed with three brass swivel guns. Brooke lost only a few men killed or wounded while at least 100 pirates were killed or wounded. Several prisoners were also released.[12][13]

Despite Spanish efforts to eradicate the pirate threat, piracy persisted until the early 1900s. Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States as a result of the Spanish–American War in 1898, after which American troops embarked on a pacification campaign from 1903 to 1913 that extended American rule to the southern Philippines and effectively suppressed piracy.[7]: 12

Ships

The pirate ships used by the Moros include various designs like the paraw, pangayaw, garay, and lanong. The majority were wooden sailing galleys (lanong) about ninety feet long with a beam of twenty feet (27.4 by 6.1 m). They carried around fifty to 100 crewmen. Moros usually armed their vessels with three swivel guns, called lelahs or lantakas, and occasionally a heavy cannon. Proas were very fast and the pirates would prey on merchant ships becalmed in shallow water as they passed through the Sulu Sea. Slave trading and raiding was also very common, the pirates would assemble large fleets of proas and attack coastal towns. Hundreds of Christians were captured and imprisoned over the centuries, many were used as galley slaves aboard the pirate ships.[14][12][unreliable source?]

Weapons

Other than muskets and rifles, the Moro pirates, as well as the navy sailors and the privateers, used a sword called the kris with a wavy blade incised with blood channels. The wooden or ivory handle was often heavily ornamented with silver or gold. The type of wound inflicted by its blade makes it difficult to heal. The kris was used often used in boarding a vessel. Moros also used a Kampilan, another sword, a knife, or barong and a spear, made of bamboo and an iron spearhead. The Moro's swivel guns were not like more modern guns used by the world powers but were of a much older technology, making them largely inaccurate, especially at sea. Lantakas dated back to the 16th century and were up to six feet long, requiring several men to lift one. They fired up to a half-pound cannonball or grape shot. A lantaka was bored by hand and were sunk into a pit and packed with dirt to hold them in a vertical position. The barrel was then bored by a company of men walking around in a circle to turn drill bits by hand.[9]: Ch. 10

Piracy after World War II

Piracy reemerged in the immediate post-WWII period as a result of the deterioration of the security situation and the wide availability of military surplus engines and modern firearms[7]: 37 . Police authorities of the newly independent Philippines were unable to get hold of the traffic of arms and goods (copra and cigarettes) by rebel groups, which was fueled by the motorisation of inter-island support [7]: 37 . Emerging pirate groups mostly stemmed from the South of the country, derived from Muslim ethnic groups. In the Northern parts of Borneo, the Tawi- Tawi pirates were specifically of concern to late British colonial rule who were said to be descendants of 19th century Samal pirates [7]: 37-38 . The authorities in North Borneo recorded 232 pirate attacks between 1959 and 1962[7]: 38 . During this period, pirates primarily targeted barter traders engaged in the copra trade, but also attacked fishing and passenger vessels and conducted coastal raids on villages. As an example, in 1985, pirates caused chaos in the town of Lahad Datu in Sabah, killing 21 people and injuring 11 others[15][16] Specifically the proliferation of arms which increased with armed insurgencies in the following years, contributed to the level of violence and threat posed by pirates in the region [7]: 42 . Philippine authorities at the time, reported more than 431 deaths and 426 missing people in the course of twelve years, resulting in an intense high threat- level for the region [7]: 43 . Victims (local seafarers and Sea Nomads) were often ordered to jump into the water (practice of ambak pare) which explains the large number of people missing[7]: 43 . The armed insurgencies of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), founded in 1972, and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), founded in 1977, provided a new impetus to piracy, with both organisations engaging in piracy to fund their armed struggle.[17]: 154 MNLF has engaged in the extortion of fishermen, threatening to attack them if they did not pay protection money[7]: 111 . Similarly, Abu Sayyaf, founded in the early 1990s, started to engage in piracy attacks, both to fund the organization and for personal financial gain[17]: 155 .

Contemporary piracy

2000–2014

Throughout the turn of the millennium, the threat of piracy remained high, with re-occurring attacks on small vessels and raids of towns and businesses on coastal villages in Sabah, mostly attributable to groups of the southern Philippines, as the main types of piratical activities[17]: 153 . At the time, specifically the 2000 Sipadan kidnappings received a lot of international media attention, resulting in an increased engagement of anti-piracy measures by the Malaysian government[17]: 155 . Subsequently, the Malaysian government increased their law enforcement agencies and established naval bases in the following years that can be found today in Semporna, Sandakan, Lahad Datu and Tawau[17]: 155 . These efforts (combined with e.g. the signing of ReCAAP and an increase in the number of law enforcement personnel showed some success and lead to a decrease in incidents. Soon, on a global scale, piracy in Southeast Asian waters was outnumbered by Somali piracy.[18]

However, in the years of 2009-2014 an upswing in the number of attacks can be attributed to Southeast Asia again, mainly due to incidents in the Strait of Malacca and South China Sea, but also raids on towns, settlements and offshore businesses re-emerged as a security threat in the Sulu and Celebes area after 2010[17]: 155 . In 2014, then, the Philippine government signed a peace deal with the MILF, that includes details about disarmament of the fighters. Yet, violence continues due to other reasons, such as attacks by other violent groups such as Abu Sayyaf or dissatisfied MILF members[17]: 156 . Regarding the nature of piracy in the Sulu Sea, attacks are mostly perpetrated by small teams of less than ten people,[19]: 276 which are usually well-armed. Overall, incidents tend to be more violent than their counterparts in other areas of the world,[17]: 154 often killing their victims by shooting them or having them jump over board, leaving them to drown.[7]: 42 Weapons used by pirates include normal handguns and rifles such as AK47, M16, M1 Garand, and FN FAL[20] Pirates almost exclusively target small vessels, including fishing vessels, passenger ships and transport vessels.[17]: 151 While the pirates primarily aim to steal personal belongings, cargo and fishers' catch, they also take hostages for ransom[17]: 152 . Especially in recent years, there has been a rise of incidents of these kind. Moreover, pirates sometimes take the vessels' outboard motors or the vessel in its entirety, either to sell later or to keep for themselves.[21]

Responses by affected nation states in the region tap into the following three different categories: maritime operations, information sharing and capacity building[18]: 83-85 . While the nation states have been historically reluctant to collectively act, upholding traditional ASEAN-principles of non- interference and sovereignty, the developments and outside pressure demanded action. Information sharing increased with the adoption of RECAAP in September 2006, and even though Malaysia and Indonesia are no contracting parties, they still engage with reporting incidents and sharing information.[18]

2014–2021

Marked by a long history of piracy, Southeast Asia as a whole saw a sharp decline of piracy and armed robbery at sea in the years 2014–2018, a reduction of 200 incidents a year to 99 in 2017.[22] However, this development is mainly due to increased efforts and enforcement mechanisms in the Straits of Malacca and cannot be transferred to the Sulu and Celebes region.[23] Since 2016, the nature of piracy in that porous area changed with the militant extremist group Abu Sayyaf re- entering the field and engaging in kidnapping- for ransom- activities.[24] The years of 2016 and 2017 thereby mark a peak, with 22 incidents and 58 abducted crew members reported throughout the first year.[25] In the beginning, mostly fishing trawlers and tug boats were targeted. After October 2016, also larger tonnage ships ended in the center of attacks.[25]: 1 Until June 2019, ReCAAP reports 29 incidents of the abduction of crew members, documenting 10 people dead.[26] In 2020, one incident (involving an attack on a fishing trawler on Jan 17 in Eastern Sabah) occurred and no other one has been reported up to August 2021.[27] Nonetheless, ReCAAP continues to warn of the risk of crew abduction and urges for a re-routing from the area of the Sulu and Celebes Seas.[27]

Nature of piracy

Contemporary attacks in the Sulu and Celebes Seas amount primarily to kidnapping for ransom (while incidents in other parts of Southeast Asia mostly constitute non- violent robberies).[22] All attacks have been committed while the ships were underway and tug and fishing boats were the main victims of abduction of crew (due to their slow speed and low freeboard)[28]: 12–14 . As the assaults are often traced back to members of Abu Sayyaf, the ransom money is most likely supporting the extremist organisation. International attention arose due to the alarming cruelty hostages are abducted and detained [22]: 33 .

State responses

Recent responses by the littoral states Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines focus, first and foremost, on the improvement and expansion of regional cooperation. Against the background of the kidnapping- for-ransom attacks in their territorial waters, the littoral states signed a Trilateral Cooperative Agreement (TCA) in July 2016 addressing the security challenge in the tri-border-area.[29] The TCA thereby lays the foundation of the maritime security coordination and encompasses regulations on extended intelligence sharing, joint border patrols and the operationalization of the Standard Operating Procedure for maritime patrols[22]: 33 . Therefore, the three countries established so- called Maritime Command Centres in Tarankan, Tawau and Bonga which serve as operation command and monitoring centres. Furthermore, drawing on combating piracy efforts in Somalia, Malaysia and the Philippines established special transit corridors ensuring a safe passage for commercial ships.[28] The transit corridors serve as safety areas for ships passing the area and are patrolled by the littoral states. Notice needs to be given to one of the Command Centres 24 hours in advance, so that adequate assistance can be assured[28]: 8 . Moreover, in 2018, in collaboration with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the three countries established a Contact Group on Maritime Crime in the Sulu and Celebes Seas.[30]

Factors and root causes

Despite efforts by Malaysian and Philippine authorities to curb piracy in the Sulu Sea, the problem continues to persist.[17]: 155 Weak maritime law enforcement, corruption, rivalries between the involved states, and unresolved territorial claims are major barriers to an effective suppression of piracy.[21]: 19–20 Security forces sometimes are involved in organising piratical activities as well, supplying weapons and intel to pirates.[19]: 278–279 The littoral nature of the Sulu Sea makes it easy for pirates to surprise victims and evade law enforcement. On land, the poor economic conditions in the area drive people to resort to various forms of crime to make a living, including piracy. Piracy, in turn, exacerbates the economic deprivation of the population, as the primary targets are locals themselves.

The continued existence of groups like Abu Sayyaf and MILF is also to blame for the prevalence of piracy. Not only do these groups engage in piracy themselves, efforts by security forces to suppress them have also drawn resources that could be used to deal with piracy.[20]: 38–39 These efforts may also drive the local population towards piracy, as security forces frequently harass farmers, depriving them of their livelihood.[17]: 234 Small arms proliferation in the area is also high as a result of weak state authority and the armed struggle of these groups, making it easy for pirates to acquire weapons[17]: 153 .

Cultural factors may also play a part, with most of modern-day pirates in the Sulu Sea being descended from their historical predecessors, adding an element of cultural sanction to piracy. It has been suggested that piracy may in part be motivated by associated virtues such as honor and masculinity, which pirates can display by taking part in an operation.[7]: 41 Piracy is also not seen as an inherently criminal activity by the population living at the edge of the Sulu Sea, which is reflected in the local languages[19]: 273–274 .

Piracy statistics

Piracy statistics on the incidents in the region mostly rely on reports issued by the Piracy Reporting Centre of the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), or the Information Sharing Centre of ReCAAP. Data from the International Maritime Organization cannot be used, as they only report from two locations, the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea.[31]

Overall, the numbers differ depending on each institutions' reporting processes, sources they derive their information from, classification mechanisms, location of attacks, types of ships attacked, their status, political considerations[31]: 18 . The IMB, for example, relies on data from shipowners, whereas the ReCAAP's ISC derives their data from official staff, naval and coast guard officers[31]: 15 . Furthermore, underreporting and overreporting are also further bias factors, as shipowners or local seafarers refuse to report incidents due to different reasons. Shipmasters, for example, often fear potential disruptions in their time schedules or a rise in insurances[31]: 16 . Attacks on local craft on fishing boats and small tugs are often not noted due to the lack of infrastructure or a lack of trust to the authorities[19]: 275 . Some incidents contrarily are reported, but without specific details on the location (threat at harbor or at sea[31]: 15 . Thus, piracy statistics demand a detailed look into the circumstances of the acquisition of data and contexts surrounding the information[31]: 17 .

Gallery

-

Piratical Proa in Full Chase

-

An engagement with pirates off Sarawak in 1843

-

Spanish warships bombarding the Moro pirates of Balanguingui in 1848

-

The Spanish landing at Balanguingui by Antonio Brugada

-

Kris from Bali

-

19th century barong from the Sulu Archipelago

-

A fight between Filipino pirates, Bugis trading ship, and Dutch mariners.

See also

- Piracy

- Piracy in the 21st century

- Slavery in the Sulu Sea

- Timawa

- Marina Sutil

- Barbary Pirates

- Caribbean Pirates

- Spanish–Moro conflict

- Philippine–American War

- Cross border attacks in Sabah

- Thalassocracy

References

- ^ Alverdian, Indra; Joas, Marko; Tynkkynen, Nina (2020). "Prospects for multi-level governance of maritime security in the Sulu-Celebes Sea: lessons from the Baltic Sea region". Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs. 12 (2): 114. doi:10.1080/18366503.2020.1770944. S2CID 219931525.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ikrami, Hadyu (2018). "Sulu-Sulawesi Seas Patrol: Lessons from the Malacca Straits Patrol and Other Similar Cooperative Frameworks". The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law. 33 (4): 800. doi:10.1163/15718085-12334092. S2CID 158983060.

- ^ Teitler, Ger (2002). "Piracy in Southeast Asia. A Historical Comparison". MAST (Maritime Studies). 1 (1): 68.

- ^ Beckmann, Robert (2013). Piracy and armed robbery against ships in Southeast Asia. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 9781849804844.

- ^ Safety 4 Sea (January 15, 2021). "ReCAAP ISC: 2020 ends with 97 piracy incidents in Asia, a 17% increase". Safety 4 Sea. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ RECAAP ISC (2020). "Annual Report. January- December 2020". Retrieved August 6, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Eklöf, Stefan (2006). Pirates in Paradise. A Modern History of Southeast Asia's Maritime Marauders. Copenhagen, Denmark. ISBN 87-91114-37-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Angeles, V.S. (2010). "Moros in the media and beyond: representations of Philippine Muslims". Contemporary Islam. 4: 29–53. doi:10.1007/s11562-009-0100-4. S2CID 144390501.

- ^ a b Hurley, Vic (Gerald Victor) (1936) [2010]. Swish of the Kris, The Story of the Moros (PDF). Christopher L. Harris 2010. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. ISBN 978-0615382425. OCLC 1837416.

- ^ Root, Elihu (1902) [2012]. Elihu Root collection of United States documents relating to the Philippine Islands. Vol. 91 pt 2. US Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1231100561.

- ^ a b c Non, Domingo (1993). "Moro Piracy during the Spanish Period and Its Impact". Southeast Asian Studies. 30 (4): 401.

- ^ a b McDougall, Harriette (1882) [2015]. Sketches of Our Life at Sarawak. SPCK. ISBN 978-1511851268. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ Sala, George Augustus & Yates, Edmund Hodgson (1868) [2011]. "The Career and Character of Rajah Brooke". Temple Bar – A London Magazine for Time and Country Readers. Vol. XXIV. Ward and Lock. pp. 204–216. ISBN 978-1173798765. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ Scholz, Herman (2006). "Discover Sabah - History". Flyingdusun.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ New Straits Times, K. P. Waran (September 24, 1987). "Lahad Datu Recalls Its Blackest Monday". p. 12. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald, Masayuki Doi (October 30, 1985). "Filipino pirates wreak havoc in a Malaysian island paradise". p. 11. Retrieved October 30, 2014..

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Liss, Carolin (2017). "Piracy and maritime violence in the waters between Sabah and the southern Philippines". In Liss, Carolin; Biggs, Ted (eds.). Piracy in Southeast Asia. Trends, Hot Spots and Responses. Abingdon, United Kingdom & New York, United States: Routledge. pp. 151–167. ISBN 978-1-138-68233-7.

- ^ a b c Davenport, Tara (2017). "Legal measures to combat piracy and armed robbery in Southeast Asia. Problems and Prospects.". In Liss, Carolin (ed.). Piracy in Southeast Asia: trends, hot spots and responses. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315545264. ISBN 9781315545264.

- ^ a b c d Tokoro, Ikuya (2006). "Piracy in Contemporary Sulu: An Ethnographical Case Study". In Kleinen, John; Osseweijer, Manon (eds.). Pirates, Ports, and Coasts in Asia: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Singapore & Leiden, The Netherlands: International Institute for Asian Studies & Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 269–287. ISBN 9789814515726.

- ^ a b Santos, Eduardo (2006). "Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in the Philippiens". In Ong-Webb, Graham Gerhard (ed.). Pirates, Ports, and Coasts in Asia: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. doi:10.1355/9789812305909. ISBN 9789812305909.

- ^ a b Abbot, Jason; Renwick, Neil (1999). "Pirates? Maritime piracy and societal security in Southeast Asia". Pacifica Review. 11 (1): 7–24. doi:10.1080/14781159908412867.

- ^ a b c d Amling, Alexandra; Bell, Curtis; Salleh, Asyura; Benson, Jay; Duncan, Sea (2019). Stable Seas: Sulu and Celebes Seas. Broomfield: Safety4Sea. p. 32.

- ^ Amling, Alexandra; Bell, Curtis; Salleh, Asyura; Benson, Jay; Duncan, Sean (2019). Stable Seas. Sulu and Celebes Seas (PDF). Broomfield: Safety 4 Sea. p. 32.

- ^ Amling, Alexandra; Bell, Curtis; Salleh, Asyura; Benson, Jay; Duncan, Sean (2019). Stable Seas. Sulu and Celebes Seas (PDF). Broomfield: Safety 4 Sea. p. 33.

- ^ a b Special Report on Abducting of Crew from Ships in the Sulu-Celebes Sea and Waters off Eastern Sabah (PDF). Singapore: ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre. March 2017.

- ^ ReCAAP, ISC (2020). Annual Report. Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (PDF). Singapore: ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre. p. 2.

- ^ a b Monthly Report August 2021 (PDF). Singapore: ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre. 2021. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Guidance on Abduction of Crew in the Sulu- Celebes Seas and Waters of Eastern Sabah (PDF). Singapore: ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre. 2019.

- ^ Safety4Sea (July 29, 2019). "ReCAAP publishes guidance for crew abduction Sulu-Celebes seas". Retrieved August 11, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Guilfoyle, Douglas (2021). "Maritime Security". In Geiß, Robin; Melzer, Niels (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the International Law of Global Security. pp. 305–306.

- ^ a b c d e f Bateman, Sam (2017). "Changes in Piracy in Southeast Asia over the last ten years". In Liss, Caroline; Biggs, Ted (eds.). Piracy in Southeast Asia. Trends, Hot Spots and Responses. London: Routledge. pp. 14–32.

Further reading

- Warren, James Francis (2007) [1st pub. 1981]. The Sulu Zone 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State (2nd ed.). Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-386-2. OCLC 834772443.

- Warren, James Francis (2002). Iranun and Balangingi: Globalization, Maritime Raiding and the Birth of Ethnicity. Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971-69-242-2. OCLC 51572722.

- Warren, James Francis (2003). "A Tale of Two Centuries: The Globalisation of Maritime Raiding and Piracy in Southeast Asia at the End of the Eighteenth and Twentieth Centuries" (PDF). Working Paper Series (2). Singapore: Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- Bateman, Sam (2017). "Changes in Piracy in Southeast Asia over the last ten years". In Liss, Caroline; Biggs, Ted (eds.). Piracy in Southeast Asia. Trends, Hot Spots and Responses. London: Routledge. pp. 14–32.

- Jeong, Keunsoo (2018). "Diverse patterns of world and regional piracy: implications of the recurrent characteristics". Australian Journal of Maritime&Ocean Affairs. 10 (2): 118–133. doi:10.1080/18366503.2018.1444935. S2CID 158544530.

- Amirell, Stefan, Bruce Buchan and Hans Hägerdal (eds) (2021) Piracy in World History. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Open Access https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/53019