2011 military intervention in Libya

| 2011 military intervention in Libya | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Libyan Civil War | |||||||

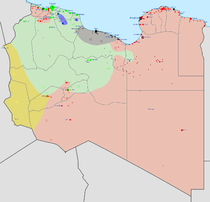

Top: The no-fly zone over Libya as well as bases and warships which were involved in the intervention Bottom: Coloured in blue are the states that were involved in implementing the no-fly zone over Libya (coloured in green) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Opération Harmattan: Operation Ellamy: Operation Mobile: Operation Odyssey Dawn: Operation Unified Protector: |

(POW)[9] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

260 aircraft 21 ships[10] |

200 medium/heavy SAM launchers 220 light SAM launchers[11] 600 anti-aircraft guns[12] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

|

72+ civilians killed (according to Human Rights Watch)[18] 40 civilians killed in Tripoli (Vatican claim)[19] 223–403 likely civilian deaths (per Airwars)[20][21] | |||||||

| The US military claimed it had no knowledge of civilian casualties.[22] | |||||||

On 19 March 2011, a multi-state NATO-led coalition began a military intervention in Libya to implement United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 (UNSCR 1973), in response to events during the First Libyan Civil War. With ten votes in favour and five abstentions, the intent of the UN Security Council was to have "an immediate ceasefire in Libya, including an end to the current attacks against civilians, which it said might constitute 'crimes against humanity' ... [imposing] a ban on all flights in the country's airspace — a no-fly zone — and tightened sanctions on the Muammar Gaddafi regime and its supporters."[23]

American and British naval forces fired over 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles, and imposed a naval blockade.[24] The French Air Force, British Royal Air Force, and Royal Canadian Air Force[25] undertook sorties across Libya.[26][27][28] The intervention did not employ foreign ground troops, with the exception of special forces, which were not covered by the UN resolution .[29][30]

The Libyan government's response to the campaign was totally ineffectual, with Gaddafi's forces not managing to shoot down a single NATO plane, despite the country possessing 30 heavy SAM batteries, 17 medium SAM batteries, 55 light SAM batteries (a total of 400–450 launchers, including 130–150 2K12 Kub launchers and some 9K33 Osa launchers), and 440–600 short-ranged air-defense guns.[12][31]

The official names for the interventions by the coalition members are Opération Harmattan by France; Operation Ellamy by the United Kingdom; Operation Mobile for the Canadian participation and Operation Odyssey Dawn for the United States.[32] Italy initially opposed the intervention but then offered to take part in the operations on the condition that NATO took the leadership of the mission instead of individual countries (particularly France). As this condition was later met, Italy shared its bases and intelligence with the allies.[33]

From the beginning of the intervention, the initial coalition of Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, Norway, Qatar, Spain, UK and US[34][35][36][37][38] expanded to nineteen states, with newer states mostly enforcing the no-fly zone and naval blockade or providing military logistical assistance. The effort was initially largely led by France and the United Kingdom, with command shared with the United States. NATO took control of the arms embargo on 23 March, named Operation Unified Protector. An attempt to unify the military command of the air campaign (whilst keeping political and strategic control with a small group), first failed over objections by the French, German, and Turkish governments.[39][40] On 24 March, NATO agreed to take control of the no-fly zone, while command of targeting ground units remains with coalition forces.[41][42][43] The handover occurred on 31 March 2011 at 06:00 UTC (08:00 local time). NATO flew 26,500 sorties since it took charge of the Libya mission on 31 March 2011.

Fighting in Libya ended in late October following the killing of Muammar Gaddafi, and NATO stated it would end operations over Libya on 31 October 2011. Libya's new government requested that its mission be extended to the end of the year,[44] but on 27 October, the Security Council unanimously voted to end NATO's mandate for military action on 31 October.[45]

It is reported that over the eight months, NATO members carried out 7,000 bombing sorties targeting Gaddafi's forces.[46]

Proposal for the no-fly zone

Both Libyan officials[47][48][49][50] and international states[51][52][53][54][55] and organizations[23][56][57][58][59][60][61] called for a no-fly zone over Libya in light of allegations that Muammar Gaddafi's military had conducted airstrikes against Libyan rebels in the Libyan Civil War.

Timeline

- 21 February 2011: Libyan deputy Permanent Representative to the UN Ibrahim Dabbashi called "on the UN to impose a no-fly zone on all of Tripoli to cut off all supplies of arms and mercenaries to the regime."[47]

- 23 February 2011: French President Nicolas Sarkozy pushed for the European Union (EU) to pass sanctions against Gaddafi (freezing Gaddafi's family funds abroad) and demand he stops attacks against civilians.

- 25 February 2011: Sarkozy said Gaddafi "must go."[62]

- 26 February 2011: United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 was passed unanimously, referring the Libyan government to the International Criminal Court for gross human rights violations. It imposed an arms embargo on the country and a travel ban and assets freeze on the family of Muammar Al-Gaddafi and certain Government officials.[63]

- 28 February 2011: British Prime Minister David Cameron proposed the idea of a no-fly zone to prevent Gaddafi from "airlifting mercenaries" and "using his military aeroplanes and armoured helicopters against civilians."[52]

- 1 March 2011: The US Senate unanimously passed non-binding Senate resolution S.RES.85 urging the United Nations Security Council to impose a Libyan no-fly zone and encouraging Gaddafi to step down. The US had naval forces positioned off the coast of Libya, as well as forces already in the region, including the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise.[64]

- 2 March 2011: The Governor General of Canada-in-Council authorized, on the advice of Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper, the deployment of the Royal Canadian Navy frigate HMCS Charlottetown to the Mediterranean, off the coast of Libya.[65] Canadian National Defence Minister Peter MacKay stated that "[w]e are there for all inevitabilities. And NATO is looking at this as well ... This is taken as a precautionary and staged measure."[64]

- 7 March 2011: US Ambassador to NATO Ivo Daalder announced that NATO decided to step up surveillance missions of E-3 AWACS aircraft to twenty-four hours a day. On the same day, it was reported that an anonymous UN diplomat confirmed to Agence France Presse that France and Britain were drawing up a resolution on the no-fly zone that would be considered by the UN Security Council during the same week.[51] The Gulf Cooperation Council also on that day called upon the UN Security Council to "take all necessary measures to protect civilians, including enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya."

- 9 March 2011: The head of the Libyan National Transitional Council, Mustafa Abdul Jalil, "pleaded for the international community to move quickly to impose a no-fly zone over Libya, declaring that any delay would result in more casualties."[48] Three days later, he stated that if pro-Gaddafi forces reached Benghazi, then they would kill "half a million" people. He stated, "If there is no no-fly zone imposed on Gaddafi's regime, and his ships are not checked, we will have a catastrophe in Libya."[49]

- 10 March 2011: France recognized the Libyan NTC as the legitimate government of Libya soon after Sarkozy met with them in Paris. This meeting was arranged by Bernard-Henri Lévy.[66]

- 12 March 2011: The Arab League "called on the United Nations Security Council to impose a no-fly zone over Libya in a bid to protect civilians from air attack."[56][57][58][67] The Arab League's request was announced by Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi bin Abdullah, who stated that all member states present at the meeting agreed with the proposal.[56] On 12 March, thousands of Libyan women marched in the streets of the rebel-held town of Benghazi, calling for the imposition of a no-fly zone over Libya.[50]

- 14 March 2011: In Paris at the Élysée Palace, before the summit with the G8 Minister for Foreign Affairs, Sarkozy, who is also the president of the G8, along with French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé met with US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and pressed her to push for intervention in Libya.[68]

- 15 March 2011: A resolution for a no-fly zone was proposed by Nawaf Salam, Lebanon's Ambassador to the UN. The resolution was immediately backed by France and the United Kingdom.[69]

- 17 March 2011: The UN Security Council, acting under the authority of Chapter VII of the UN Charter, approved a no-fly zone by a vote of ten in favour, zero against, and five abstentions, via UNSCR 1973. The five abstentions were: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and Germany.[59][60][61][70][71] Less than twenty-four hours later, Libya announced that it would halt all military operations in response to the UN Security Council resolution.[72][73]

- 18 March 2011: The Libyan foreign minister, Moussa Koussa, said that he had declared a ceasefire, attributing the UN resolution.[74] However, artillery shelling on Misrata and Ajdabiya continued, and government soldiers continued approaching Benghazi.[24][75] Government troops and tanks entered the city on 19 March.[76] Artillery and mortars were also fired into the city.[77]

- 18 March 2011: U.S. President Barack Obama orders military air strikes against Muammar Gaddafi's forces in Libya in his address to the nation from the White House.[78] US President Obama later held a meeting with eighteen senior lawmakers at the White House on the afternoon of 18 March[79]

- 19 March 2011: French[80] forces began the military intervention in Libya, later joined by coalition forces with strikes against armoured units south of Benghazi and attacks on Libyan air-defense systems, as UN Security Council Resolution 1973 called for using "all necessary means" to protect civilians and civilian-populated areas from attack, imposed a no-fly zone, and called for an immediate and with-standing cease-fire, while also strengthening travel bans on members of the regime, arms embargoes, and asset freezes.[23]

- 21 March 2011: Obama sent a letter to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate claiming the actions were justified under the War Powers Resolution.[81]

- 24 March 2011: In telephone negotiations, French foreign minister Alain Juppé agreed to let NATO take over all military operations on 29 March at the latest, allowing Turkey to veto strikes on Gaddafi's ground forces from that point forward.[82] Later reports stated that NATO would take over enforcement of the no-fly zone and the arms embargo, but discussions were still underway about whether NATO would take over the protection of civilians mission. Turkey reportedly wanted the power to veto airstrikes, while France wanted to prevent Turkey from having such a veto.[83][84]

- 25 March 2011: NATO Allied Joint Force Command in Naples took command of the no-fly zone over Libya and combined it with the ongoing arms embargo operation under the name Operation Unified Protector.[85]

- 26 March 2011: Obama addressed the nation from the White House, providing an update on the current state of the military intervention in Libya.[86]

- 28 March 2011: Obama addressed the American people on the rationale for U.S. military intervention with NATO forces in Libya at the National Defense University.[87]

- 20 October 2011: When Hillary Clinton learned of the death of Muammar Gaddafi she was covered to have said: "We came, we saw, he died" in paraphrasing the famous quote of the Roman imperator Julius Caesar veni, vidi, vici.[88]

Enforcement

Initial NATO planning for a possible no-fly zone took place in late February and early March,[89] especially by NATO members France and the United Kingdom.[90] France and the UK were early supporters of a no-fly zone and had sufficient airpower to impose a no-fly zone over the rebel-held areas, although they might need additional assistance for a more extensive exclusion zone.

The US had the air assets necessary to enforce a no-fly zone, but was cautious about supporting such an action prior to obtaining a legal basis for violating Libya's sovereignty. Furthermore, due to the sensitive nature of military action by the US against an Arab nation, the US sought Arab participation in the enforcement of a no-fly zone.

At a congressional hearing, United States Secretary of Defense Robert Gates explained that "a no-fly zone begins with an attack on Libya to destroy the air defences … and then you can fly planes around the country and not worry about our guys being shot down. But that's the way it starts."[91]

On 19 March, the deployment of French fighter jets over Libya began,[26] and other states began their individual operations. Phase One started the same day with the involvement of the United States, United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Canada.[citation needed]

On 24 March, NATO ambassadors agreed that NATO would take command of the no-fly zone enforcement, while other military operations remained the responsibility of the group of states previously involved, with NATO expected to take control as early as 26 March.[92] The decision was made after meetings of NATO members to resolve disagreements over whether military operations in Libya should include attacks on ground forces.[92] The decision created a two-level power structure overseeing military operations. In charge politically was a committee, led by NATO, that included all states participating in enforcing the no-fly zone, while NATO alone was responsible for military action.[93] Royal Canadian Air Force Lieutenant-General Charles Bouchard has been appointed to command the NATO military mission.[94]

After the death of Muammar Gaddafi on 20 October 2011, it was announced that the NATO mission would end on 31 October.[95]

Operation names

Before NATO took full command of operations at 06:00 GMT on 31 March 2011, the military intervention in the form of a no-fly zone and the naval blockade was split between different national operations:

- France: Opération Harmattan

- United Kingdom: Operation Ellamy

- Canada: Operation Mobile

- United States: Operation Odyssey Dawn – Belgium, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Qatar, Spain, Greece and the United Arab Emirates placed their national contributions under U.S. command

Forces committed

These are the forces committed in alphabetical order:

- Belgium: Six F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter jets of the Belgian Air Component, were already stationed at Araxos, Greece for an exercise, and flew their first mission in the afternoon of 21 March. They monitored the no-fly zone throughout the operation and have successfully attacked ground targets multiple times since 27 March, all of them without collateral damage. The Belgian Naval Component minehunter Narcis was part of NATO's SNMCMG1 at the start of the operation and assisted in NATO's naval blockade from 23 March. The ship was later replaced by the minehunter Lobelia in August.

- Bulgaria: The Bulgarian Navy Wielingen-class frigate Drazki participated in the naval blockade, along with a number of "special naval forces", two medical teams and other humanitarian help.[96][97][98] The frigate left port on 27 April and arrived off the coast of Libya on 2 May.[99] It patrolled for one month before returning to Bulgaria, with a supply stop at the Greek port of Souda.

- Canada: The Royal Canadian Air Force deployed seven (six front line, one reserve) CF-18 fighter jets, two CC-150 Polaris refueling airplanes, two CC-177 Globemaster III heavy transports, two CC-130J Super Hercules tactical transports, and two CP-140 Aurora maritime patrol aircraft. The Royal Canadian Navy deployed the Halifax-class frigates HMCS Charlottetown and HMCS Vancouver. A total of 440 Canadian Forces personnel participated in Operation Mobile. There were reports that special operations were being conducted by Joint Task Force 2 in association with Britain's Special Air Service (SAS) and Special Boat Service (SBS) as part of Canada's contribution.[100][101][102][103][104]

- Denmark: The Royal Danish Air Force participated with six F-16AM fighters, one C-130J Super Hercules military transport plane and the corresponding ground crews. Only four F-16s were used for offensive operations, while the remaining two acted as reserves.[105] The first mission by Danish aircraft was flown on 20 March and the first strikes were carried out on 23 March, with four aircraft making twelve sorties as part of Operation Odyssey Dawn.[106] Danish F-16s flew a total of 43 missions dropping 107 precision bombs during Odyssey Dawn before switching to NATO command under Unified Protector[107] Danish flights bombed approximately 17% of all targets in Libya and together with Norwegian flights proved to be the most efficient in proportion to the number of flights involved.[108] Danish F-16s flew the last fast-jet mission of Operation Unified Protector on 31 October 2011[109] finishing with a total of 599 missions flown and 923 precision bombs dropped during the entire Libya intervention.[110]

- France: The French Air Force, which flew the highest percentage of NATO's strikes (35%), participated in the mission with 18 Mirage, 19 Rafale, 6 Mirage F1, 6 Super Etendard, 2 E-2 Hawkeye, 3 Eurocopter Tiger, 16 Aérospatiale Gazelle aircraft. In addition, the French Navy anti-air destroyer Forbin and the frigate Jean Bart participated in the operations.[111] On 22 March, the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle arrived in international waters near Crete to provide military planners with a rapid-response air combat capability.[112] Accompanying Charles de Gaulle were the frigates Dupleix, Aconit, the fleet replenishment tanker Meuse, and one Rubis-class nuclear attack submarine.[113] France did station three Mirage 2000-5 aircraft and six Mirage 2000D at Souda Bay, Crete.[114] France also sent an amphibious assault helicopter carrier, the Tonnerre (relieved on 14 July by Mistral[115]), carrying 19 rotorcraft to operate off the coast of Libya.[116] The French Air Force and Navy flew 5600 sorties[117] (3100 CAS, 1200 reconnaissance, 400 air superiority, 340 air control, 580 air refueling) and delivered 1205 precision guided munitions (950 LGB and 225 AASM "hammer" missiles, 15 SCALP missiles).[118] Helicopter forces from Army Aviation aboard Tonnerre and Mistral LHD performed 41 night raids, 316 sorties, and destroyed 450 military objectives. The ammunition delivered were 432 Hot Missiles, 1500 68-mm rockets and 13,500 20- and 30-mm shells by Gazelle and Tigre helicopters. The French Navy provided Naval gunfire support and fired 3000 76- and 100-mm shells from the Jean Bart, Lafayette, Forbin, and Chevalier Paul destroyers.

- Greece: The Elli-class frigate Limnos of the Hellenic Navy was deployed to the waters off Libya as part of the naval blockade.[119] The Hellenic Air Force provided Super Puma search-and-rescue helicopters and few Embraer 145 AEW&C airborne radar planes.[114][120][121][122]

- Italy: At the beginning of the operation, as a contribution to enforce the no-fly zone, the Italian government committed four Tornado ECRs of the Italian Air Force in SEAD operations, supported by two Tornado IDS variants in an air-to-air refueling role and four F-16ADF fighters as an escort.[123] After the transfer of authority to NATO and the decision to participate in strike air-ground operations, the Italian government increased the Italian contribution by adding four Italian Navy AV-8B plus (from Italian aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi), four Italian Air Force Eurofighters, and four Tornado IDSs under NATO command. Other assets under national command participated in air patrolling and air refueling missions.[124] As of 24 March, the Italian Navy was engaged in Operation Unified Protector with the light aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi, the Maestrale-class frigate Libeccio and the auxiliary ship Etna.[125] Additionally, the Orizzonte-class destroyer Andrea Doria and Maestrale-class frigate Euro were patrolling off the Sicilian coast in an air-defence role.[126][127] At a later stage, Italy increased its contribution to the NATO led mission by doubling the number of AV-8B Harriers and deploying an undisclosed number of AMX fighter-bombers and KC-130J and KC-767A tanker planes. The Italian Air Force also deployed its MQ-9A Reaper UAVs for real time video reconnaissance.[128]

- Jordan: Six Royal Jordanian Air Force fighter jets landed at a coalition airbase in Europe on 4 April to provide "logistical support" and act as an escort for Jordanian transport aircraft using the humanitarian corridor to deliver aid and supplies to opposition-held Cyrenaica, according to Foreign Minister Nasser Judeh. He did not specify the type of aircraft or what specific roles they may be called upon to perform, though he said they were not intended for combat.[129]

- NATO: E-3 airborne early warning and control (AWACS) aircraft operated by NATO and crewed by member states helped monitor the airspace over the Mediterranean and in Libya.[130]

- Netherlands: The Royal Netherlands Air Force provided six F-16AM fighters and a KDC-10 refueling plane. These aircraft were stationed at the Decimomannu Air Base on Sardinia. Four F-16s flew patrols over Libya, while the other two were kept in reserve.[131] Additionally, the Royal Netherlands Navy deployed the Tripartite-class minehunter HNLMS Haarlem to assist in enforcing the weapons embargo.[132]

- Norway: The Royal Norwegian Air Force deployed six F-16AM fighters to Souda Bay Air Base with corresponding ground crews.[133][134][135] On 24 March, the Norwegian F-16s were assigned to the US North African command and Operation Odyssey Dawn. It was also reported that Norwegian fighters along with Danish fighters had bombed the most targets in Libya in proportion to the number of planes involved.[108] On 24 June, the number of fighters deployed was reduced from six to four.[136] The Norwegian participation in the military efforts against the Libyan government came to an end in late July 2011, by which time Norwegian aircraft had dropped 588 bombs and carried out 615 of the 6493 NATO missions between 31 March and 1 August (not including 19 bombs dropped and 32 missions carried out under operation Odyssey Dawn). 75% of the missions performed by the Royal Norwegian Air Force were so-called SCAR (Strike Coordination and Reconnaissance) missions. US military sources confirmed that on the night of 25 April, two F-16s from the Royal Norwegian Air Force bombed the residence of Gaddafi inside Tripoli.[137][138]

- Qatar: The Qatar Armed Forces contributed with six Mirage 2000-5EDA fighter jets and two C-17 strategic transport aircraft to coalition no-fly zone enforcement efforts.[139] The Qatari aircraft were stationed in Crete.[112] At later stages in the Operation, Qatari Special Forces had been assisting in operations, including the training of the Tripoli Brigade and rebel forces in Benghazi and the Nafusa mountains. Qatar also brought small groups of Libyans to Qatar for small-unit leadership training in preparation for the rebel advance on Tripoli in August.[140]

- Romania: The Romanian Naval Forces participated in the naval blockade with the frigate Regele Ferdinand.[141]

- Spain: The Spanish Armed Forces participated with six F-18 fighters, two Boeing 707-331B(KC) tanker aircraft, the Álvaro de Bazán-class frigate Méndez Núñez, the submarine Tramontana and two CN-235 MPA maritime surveillance planes. Spain participated in air control and maritime surveillance missions to prevent the inflow of arms to the Libyan regime. Spain also made the Spanish air base at Rota available to NATO.[142]

- Sweden: The Swedish Air Force committed eight JAS 39 Gripen jets for the international air campaign after being asked by NATO to take part in the operations on 28 March.[143][144][145] Sweden also sent a Saab 340 AEW&C for airborne early warning and control and a C-130 Hercules for aerial refueling.[146] Sweden was the only country neither a member of NATO nor the Arab League to participate in the no-fly zone.

- Turkey: The Turkish Navy participated by sending the Barbaros-class frigates, TCG Yildirim & TCG Orucreis, the Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates, TCG Gemlik & TCG Giresun, the tanker TCG Akar, and the submarine TCG Yildiray to the NATO-led naval blockade to enforce the arms embargo.[147] It also provided six F-16 jets for aerial operations.[148] On 24 March, Turkey's parliament approved Turkish participation in military operations in Libya, including enforcing the no-fly zone in Libya.[149]

- United Arab Emirates: On 24 March, the United Arab Emirates Air Force sent six F-16 and six Mirage 2000 fighter jets to join the mission. This was also the first combat deployment of the Desert Falcon variant of F-16, which was the most sophisticated F-16 variant at the time. The planes were based at the Italian Decimomannu air base on Sardinia.[150][151]

- United Kingdom: The UK deployed the Royal Navy frigates HMS Westminster and HMS Cumberland, nuclear attack submarines HMS Triumph and HMS Turbulent, the destroyer HMS Liverpool and the mine countermeasure vessel HMS Brocklesby.[152] The Royal Air Force participated with 16 Tornado and 10 Typhoon fighters[153] operating initially from Great Britain, but later forward deployed to the Italian base at Gioia del Colle. Nimrod R1 and Sentinel R1 surveillance aircraft were forward deployed to RAF Akrotiri in support of the action. In addition, the RAF deployed a number of other support aircraft such as the Sentry AEW.1 AWACS aircraft and VC10 air-to-air refueling tankers. According to anonymous sources, members of the SAS, SBS, and Special Reconnaissance Regiment (SRR) helped to coordinate the air strikes on the ground in Libya.[154] On 27 May, the UK deployed four UK Apache helicopters on board HMS Ocean.[155]

- United States: The US deployed a naval force of 11 ships, including the amphibious assault ship USS Kearsarge, the amphibious transport dock USS Ponce, the guided-missile destroyers USS Barry and USS Stout, the nuclear attack submarines USS Providence and USS Scranton, the cruise missile submarine USS Florida and the amphibious command ship USS Mount Whitney.[156][157] Additionally, A-10 ground-attack aircraft, two B-1B bombers,[158] three Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit stealth bombers,[159] AV-8B Harrier II jump-jets, EA-18G Growler electronic warfare aircraft, P-3 Orions, and both McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle[160] and F-16 fighters were involved in action over Libya.[161] U-2 reconnaissance aircraft were stationed on Cyprus. On 18 March, two AC-130Us arrived at RAF Mildenhall as well as additional tanker aircraft.[citation needed] On 24 March 2 E-8Cs operated from Naval Station Rota Spain, which indicated an increase of ground attacks.[citation needed] An undisclosed number of CIA operatives were said to be in Libya to gather intelligence for airstrikes and make contacts with rebels.[162] The US also used MQ-1 Predator UAVs to strike targets in Libya on 23 April.[163]

-

USS Florida launching a Tomahawk cruise missile

-

Naval blockade by British frigate HMS Cumberland (here pictured with USS Dwight D. Eisenhower in view)

-

Italian aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi

-

American stealth bomber, B-2 Spirit

-

Qatari Dassault Mirage 2000 fighter jet

-

Swedish Saab S 100B Argus airborne early warning

-

Spanish KC-135 refuels two F-18s

-

A CF-18 Hornet of the Royal Canadian Air Force

-

An F-16 Fighting Falcon of the Belgian Air Component

-

French Destroyer Chevalier Paul provided naval gun support

-

Italian Destroyer Andrea Doria provided air-defence role

-

French Assault ship Tonnere

-

French Rafale receives fuel from a KC-10

Bases committed

- France: Saint-Dizier, Dijon, Nancy, Istres, Solenzara, Avord[164]

- Greece: Souda, Aktion, Araxos, and Andravida[112][122][165]

- Italy: Amendola, Decimomannu, Gioia del Colle, Trapani, Pantelleria, Capodichino[166]

- Spain: Rota, Morón, Torrejón[167]

- Turkey: Incirlik, İzmir[168][169]

- United Kingdom: RAF Akrotiri, RAF Marham, RAF Waddington, RAF Leuchars, RAF Brize Norton, Aviano (IT)[170]

- United States: Aviano (IT), RAF Lakenheath (UK), RAF Mildenhall (UK), Sigonella (IT), Spangdahlem (GE),[171] Ellsworth AFB (US)

Actions by other states

- Albania: Prime Minister Sali Berisha said that Albania was ready to help. Berisha supported the decision of the coalition to protect civilians from the Gaddafi regime. He also offered assistance to facilitate the coalition's actions. A press release from the Prime Minister's office stated that these operations are entirely legitimate, with their main objective being the protection of freedom and the universal rights that Libyans deserve.[172] On 29 March, Foreign Minister Edmond Haxhinasto said Albania would open its airspace and territorial waters to coalition forces and said its seaports and airports were at the coalition's disposal upon request. He also suggested that Albania could help with international humanitarian efforts.[173] In mid-April, the International Business Times listed Albania alongside several other NATO member states, including Romania and Turkey, that have made modest contributions to the military effort, but it did not go into detail.[174][better source needed]

- Australia: Prime Minister Julia Gillard and others in her Labor government said Australia would not contribute militarily to enforcement of the UN mandate despite registering strong support for the mandate. The opposition Liberal Party's defence spokesman called upon the government to consider dispatching Australian military assets if requested by NATO.[175] Defence Minister Stephen Smith said the government would be willing to send C-17 Globemaster heavy transport planes for use in international operations "as part of a humanitarian contribution", if needed.[176] On 27 April Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd described Australia as the "third largest [humanitarian contributor to Libya] globally after the United States and the European Union", after a humanitarian aid ship funded by the Australian government docked in Misrata.[177]

- Croatia: President Ivo Josipović said that if necessary Croatia would honour its NATO membership and participate in actions in Libya. He also stressed that while Croatia was ready for military participation according to its capabilities, it would mostly endeavor to help on the humanitarian side.[178] On 29 April, the government announced it planned to send two Croatian Army officers to assist with Operation Unified Protector, pending formal presidential and parliamentary approval.[179]

- Cyprus: After the passage of UNSCR 1973, President Demetris Christofias asked the British government not to use its military base at Akrotiri, an overseas territory of the UK on the island, in support of the intervention. However, this request had no legal weight as Cyprus could not legally bar the UK from using the base.[180] The Cypriot government reluctantly allowed Qatar Emiri Air Force fighter jets and a transport plane to refuel at Larnaca International Airport on 22 March after their pilots declared a fuel emergency while in transit to Crete for participation in military operations.[181]

- Estonia: Foreign Minister Urmas Paet said on 18 March that his country had no current plans to join in military operations in Libya, but it would be willing to participate if called on to do so by NATO or the EU.[182] The Estonian Air Force does not as of 2023[update] operate any combat aircraft, although it does operate a few helicopters and transport planes.[183]

- European Union: Finnish Foreign Minister Alexander Stubb announced that the proposed EUFOR Libya operation was being prepared, and was waiting for a request from the UN.[184]

- Germany: In March the country withdrew all its forces from NATO operations in the Mediterranean Sea, as its government decided not to take part in any military operations against Libya. However, it was increasing the number of AWACS personnel in Afghanistan by up to 300 to free up the forces of other states. Germany allowed the usage of military installations in its territory for intervention in Libya.[185][186][187][188] On 8 April, German officials suggested that the country could potentially contribute troops to "[ensure] with military means that humanitarian aid gets to those who need it".[189] As of early June, the German government was reportedly considering opening a center for training police in Benghazi.[190] On 24 July, Germany lent 100 million Euros (144 million US dollars) to the rebels for "civilian and humanitarian purposes".

- Indonesia: President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono called for a ceasefire by all sides, but said that if a UN peacekeeping force was established to monitor a potential truce, "Indonesia is more than willing to take part."[191]

- Kuwait: The Arab state would make a "logistic contribution", according to British Prime Minister David Cameron.[192][193]

- Malta: Prime Minister Lawrence Gonzi said no coalition forces would be allowed to stage from military bases in Malta, but Maltese airspace would be open to international forces involved in the intervention.[194] On 20 April, two French Mirages were reportedly allowed to make emergency landings in Malta after running low on fuel.[195]

- Poland: US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, UK Secretary of Defence Liam Fox, and NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen urged the Polish government to contribute to military operations. As of June, Warsaw had not committed to participation.[196][needs update]

- Sudan: The government "quietly granted permission" for coalition states to traverse its airspace for operations in the Libyan theatre if necessary, Reuters reported in late March.[197]

Civilian losses

- 14 May: NATO air strike hit a large number of people gathered for Friday prayers in the eastern city of Brega leaving 11 religious leaders dead and 50 others wounded.[198]

- 24 May: NATO air strikes in Tripoli kill 19 civilians and wound 150, according to Libyan state television.[199]

- 31 May: Libya claims that NATO strikes have left up to 718 civilians dead.[200]

- 19 June: NATO air strikes hit a residential house in Tripoli, killing seven civilians, according to Libyan state television.[201]

- 20 June: A NATO airstrike in Sorman, near Tripoli, killed fifteen civilians, according to government officials.[202] Eight rockets apparently hit the compound of a senior government official, in an area where NATO confirmed operations had taken place.[202]

- 25 June: NATO strikes on Brega hit a bakery and a restaurant, killing 15 civilians and wounding 20 more, Libyan state television claimed. The report further accused the coalition of "crimes against humanity". The claims were denied by NATO.[203]

- 28 June: NATO airstrike on the town of Tawergha, 300 km east of the Libyan capital, Tripoli kills eight civilians.[citation needed]

- 25 July: NATO airstrike on a medical clinic in Zliten kills 11 civilians, though the claim was denied by NATO, who said they hit a vehicle depot and communications center.[204][205]

- 20 July: NATO attacks Libyan state TV, Al-Jamahiriya. Three journalists killed.[206]

- 9 August: Libyan government claims 85 civilians were killed in a NATO airstrike in Majer, a village near Zliten. A spokesman confirms that NATO bombed Zliten at 2:34 a.m. on 9 August,[207] but says he was unable to confirm the casualties. Commander of the NATO military mission, Lieutenant General Charles Bouchard says "I cannot believe that 85 civilians were present when we struck in the wee hours of the morning, and given our intelligence. But I cannot assure you that there were none at all".[208]

- 15 September: Gaddafi spokesman Moussa Ibrahim declares that NATO air strikes killed 354 civilians and wounded 700 others, while 89 other civilians are supposedly missing. He also claims that over 2,000 civilians have been killed by NATO air strikes since 1 September.[209] NATO denied the claims, saying they were unfounded.[210]

- 2 March 2012: United Nations Human Rights Council release their report about the aftermath of the Libyan civil war, concluding that in total 60 civilians were killed and 55 wounded by the NATO air campaign. In the same report, the UN Human Rights Council concludes that NATO "conducted a highly precise campaign with a demonstrable determination to avoid civilian casualties".[211] In May that same year, Human Rights Watch published a report claiming that at least 72 civilians were killed.[18]

Military losses on the coalition side

- 22 March 2011: One USAF F-15E flying from Aviano crashed in Bu Marim, northwest of Benghazi. The pilot was rescued alive by US Marines from the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit based on the USS Kearsarge. The weapons systems officer evaded hostile forces and was subsequently repatriated by undisclosed forces.[212][213] The aircraft crashed due to a mechanical failure.[214] The rescue operation involved two Bell-Boeing V-22 Osprey aircraft, two Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters, and two McDonnell Douglas AV-8B Harrier II aircraft, all launched from the USS Kearsarge.[215] The operation involved the Harriers' dropping 227 kg (500 lb) bombs and strafing the area around the crash site before an Osprey recovered at least one of the downed aircraft's crew;[215][216] injuring six local civilians in the process.[217][218]

- 27 April 2011: An F-16 from the United Arab Emirates Air Force crashed at Naval Air Station Sigonella at about 11:35 local time; the pilot ejected safely.[219] The aircraft was confirmed to be from the UAE by the country's General Command of the armed forces, and had been arriving from Sardinia when it crashed.[219]

- 21 June 2011: An unmanned US Navy MQ-8 Fire Scout went down over Libya, possibly due to enemy fire.[13] NATO confirmed that they lost radar contact with the unmanned helicopter as it was performing an intelligence and reconnaissance mission near Zliten.[13] NATO began investigating the crash shortly after it occurred.[13] On 5 August, it was announced that the investigation had concluded that the cause of the crash was probably enemy fire; with an operator or mechanical failure ruled out and the inability of investigators to access the crash site the "logical conclusion" was that the aircraft had been shot down.[220]

- 20 July 2011: A British airman was killed in a traffic accident in Italy while part of a logistical convoy transferring supplies from the UK to NATO bases in the south of Italy from which air strikes were being conducted against Libya.[221][222]

Reaction

Since the start of the campaign, there have been allegations of violating the limits imposed upon the intervention by Resolution 1973 and by US law. At the end of May 2011, Western troops were captured on film in Libya, despite Resolution 1973 specifically forbidding "a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory".[223]

In a March 2011 Gallup poll, 47% of Americans had approved of military action against Libya, compared with 37% disapproval.[224]

On 10 June, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates criticized some of the NATO member nations for their efforts, or lack thereof, to participate in the intervention in Libya. Gates singled out Germany, Poland, Spain, Turkey, and the Netherlands for criticism. He praised Canada, Norway, and Denmark, saying that although those three countries had only provided 12% of the aircraft to the operation, their aircraft had conducted one-third of the strikes.[225]

On 24 June, the US House voted against Joint Resolution 68, which would have authorized continued US military involvement in the NATO campaign for up to one year.[226][227] The majority of Republicans voted against the resolution,[228] with some questioning US interests in Libya and others criticizing the White House for overstepping its authority by conducting a military expedition without Congressional backing. House Democrats were split on the issue, with 115 voting in favor of and 70 voting against. Despite the failure of the President to receive legal authorization from Congress, the Obama administration continued its military campaign, carrying out the bulk of NATO's operations until the overthrow of Gaddafi in October.

On 9 August, the head of UNESCO, Irina Bokova deplored a NATO strike on Libyan State TV, Al-Jamahiriya, that killed 3 journalists and wounded others.[229] Bokova declared that media outlets should not be the target of military activities. On 11 August, after the NATO airstrike on Majer (on 9 August) that allegedly killed 85 civilians, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called on all sides to do as much as possible to avoid killing innocent people.[230]

According to a Gallup poll conducted in March and April 2012, a survey involving 1,000 Libyans showed 75% of Libyans were in favor of the NATO intervention, compared to 22% who were opposed.[231] A post-war Orb International poll involving 1,249 Libyans found broad support for the intervention, with 85% of Libyans saying that they strongly supported the action taken to remove the Ghadafi regime.[232]

Responsibility to protect

The military intervention in Libya has been cited by the Council on Foreign Relations as an example of the responsibility to protect policy adopted by the UN at the 2005 World Summit.[233] According to Gareth Evans, "[t]he international military intervention (SMH) in Libya is not about bombing for democracy or Muammar Gaddafi's head. Legally, morally, politically, and militarily it has only one justification: protecting the country's people."[233] However, the council also noted that the policy had been used only in Libya, and not in countries such as Côte d'Ivoire, undergoing a political crisis at the time, or in response to protests in Yemen.[233] A CFR expert, Stewert Patrick, said that "There is bound to be selectivity and inconsistency in the application of the responsibility to protect norm given the complexity of national interests at stake in...the calculations of other major powers involved in these situations."[233] In January 2012, the Arab Organization for Human Rights, Palestinian Centre for Human Rights and the International Legal Assistance Consortium published a report describing alleged human rights violations and accusing NATO of war crimes.[234]

United States Congress

On 3 June 2011, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution, calling for a withdrawal of the United States military from the air and naval operations in and around Libya. It demanded that the administration provide, within 14 days, an explanation of why the President Barack Obama did not come to Congress for permission to continue to take part in the mission.[235]

On 13 June, the House passed a resolution prohibiting the use of funds for operations in the conflict, with 110 Democrats and 138 Republicans voting in favor.[236][237] Harold Koh, the State department's legal advisor, was called to testify in front of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations to defend the actions of the Obama administration under the War Powers Resolution.[238] Koh was questioned by the Committee on the Obama administration's interpretation of the word "hostilities" under the War Powers Resolution § 4(a)(1) and 5(b).[238] Koh reasoned that under the constitution, the term "hostilities" was left up for interpretation by the executive branch, and therefore the interpretation fit the historical definition of that word. Koh argued that historically the term "hostilities" has previously been used to mean limited military action acting in support of a conflict, and the scope of this operation suits that interpretation.[239] Ultimately the Committee still remained concerned by the actions of the President.[239]

On 24 June, the House rejected Joint Resolution 68, which would have provided the Obama administration with authorization to continue military operations in Libya for up to one year.[240]

Criticism

The military intervention was criticized, both at the time and subsequently, on a variety of grounds.

United Kingdom Parliament investigation

An in-depth investigation into the Libyan intervention and its aftermath was conducted by the UK Parliament's House of Commons' cross-party Foreign Affairs Committee, the final conclusions of which were released on 14 September 2016 in a report titled Libya: Examination of intervention and collapse and the UK's future policy options. The Foreign Affairs Select Committee saw no evidence that the UK Government carried out a proper analysis of the nature of the rebellion in Libya and it "selectively took elements of Muammar Gaddafi's rhetoric at face value; and it failed to identify the militant Islamist extremist element in the rebellion. UK strategy was founded on erroneous assumptions and an incomplete understanding of the evidence".[241] The report was strongly critical of the British government's role in the intervention.[242][243] The report concluded that the government "failed to identify that the threat to civilians was overstated and that the rebels included a significant Islamist element."[244] In particular, the committee concluded that Gaddafi was not planning to massacre civilians, and that reports to the contrary were propagated by rebels and Western governments.[245][241][246]

Allegations of no evidence of civilian massacres by Gaddafi

Alison Pargeter, a freelance Middle East and North Africa (MENA) analyst, told the Committee that when Gaddafi's forces re-took Ajdabiya they did not attack civilians, and this had taken place in February 2011, shortly before the NATO intervention.[247] She also said that Gaddafi's approach towards the rebels had been one of "appeasement", with the release of Islamist prisoners and promises of significant development assistance for Benghazi.[247][non-primary source needed] However, evidence which was collected during the intervention suggested otherwise, showing things such as shooting deaths of hundreds of protestors, reports of mass rapes by Libyan Armed Forces and orders from Gaddafi's senior generals to bombard and starve the people of Misrata.[248][249][250]

In his March 28th address, Barack Obama warned of an imminent risk of a massacre in Benghazi.[251] However, journalist S.Awan argued that the subsequent airstrikes "destroyed a very small convoy of government vehicles, including ambulances."[252] Furthermore, Professor Alan J. Kuperman argued against the idea of an imminent massacre in Benghazi, arguing that in captured cities such as Zawiya, Misurata and Ajdabiya no massacre had occurred, so Kuperman believed that there was little reason to think Benghazi would be any different.[252] While there were civilian casualties, he argued that there was no effort to target civilian concentrations, with Libya's air force primarily targeting rebel positions.[253]

Briefing to Hillary Clinton

According to the report, France's motive for initiating the intervention was economic and political as well as humanitarian. In a briefing to Hillary Clinton on 2 April 2011, her adviser Sidney Blumenthal reported that, according to high-level French intelligence, France's motives for overthrowing Gaddafi were to increase France's share of Libya's oil production, strengthen French influence in Africa, and improve President Sarkozy's standing at home.[254] The report also highlighted how Islamic extremists had a large influence on the uprising, which was largely ignored by the West to the future detriment of Libya.[242][243]

The American Libertarian Party opposed the U.S. military intervention.[255] Former Green Party presidential candidate Ralph Nader branded President Obama as a "war criminal"[256] and called for his impeachment.[257]

Resource control

Some critics of Western military intervention suggested that resources—not democratic or humanitarian concerns—were the real impetus for the intervention, among them a journalist of London Arab nationalist newspaper Al-Quds Al-Arabi, the Russian TV network RT and the (then-)leaders of Venezuela and Zimbabwe, Hugo Chávez and Robert Mugabe.[258][259][260] Gaddafi's Libya, despite its relatively small population, was known to possess vast resources, particularly in the form of oil reserves and financial capital.[261][better source needed]

Criticism from world leaders

The intervention prompted a widespread wave of criticism from several world leaders, including: Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei (who said he supported the rebels but not Western intervention[260]), Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez (who referred to Gaddafi as a "martyr"[259]), South African President Jacob Zuma,[262][failed verification] and President of Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe (who referred to the Western nations as "vampires"[258]), as well as the governments of Raúl Castro in Cuba,[263] Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua,[264] Kim Jong-il in North Korea,[265] Hifikepunye Pohamba in Namibia,[266] Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus,[267][268][269] and others. Gaddafi himself referred to the intervention as a "colonial crusade … capable of unleashing a full-scale war",[270] a sentiment that was echoed by Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin: "[UNSC Resolution 1973] is defective and flawed...It allows everything. It resembles medieval calls for crusades."[271] President Hu Jintao of the People's Republic of China said, "Dialogue and other peaceful means are the ultimate solutions to problems," and added, "If military action brings disaster to civilians and causes a humanitarian crisis, then it runs counter to the purpose of the UN resolution."[272] Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was critical of the intervention as well, rebuking the coalition in a speech at the UN in September 2011.[273] Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, despite the substantial role his country played in the NATO mission, also spoke out against getting involved: "I had my hands tied by the vote of the parliament of my country. But I was against and I am against this intervention which will end in a way that no-one knows" and added, "This wasn't a popular uprising because Gaddafi was loved by his people, as I was able to see when I went to Libya."[274][275]

Despite its stated opposition to NATO intervention, Russia abstained from voting on Resolution 1973 instead of exercising its veto power as a permanent member of the Security Council; four other powerful nations also abstained from the vote—India, China, Germany, and Brazil—but of that group only China has the same veto power.[276]

House of Representatives

House of Representatives  General National Congress

General National Congress  Ansar al-Sharia

Ansar al-Sharia  Islamic State

Islamic State  Tuareg

TuaregOther criticisms

Micah Zenko argues that the Obama administration deceived the public by pretending the intervention was intended to protect Libyan civilians instead of achieving regime change when "in truth, the Libyan intervention was about regime change from the very start".[277]

A 2013 paper by Alan Kuperman argued that NATO went beyond its remit of providing protection for civilians and instead supported the rebels by engaging in regime change. It argued that NATO's intervention likely extended the length (and thus damage) of the civil war, which Kuperman argued could have ended in less than two months without NATO intervention. The paper argued that the intervention was based on a misperception of the danger Gaddafi's forces posed to the civilian population, which Kuperman suggests was caused by existing bias against Gaddafi due to his past actions (such as support for terrorism), sloppy and sensationalistic journalism during the early stages of the war and propaganda from anti-government forces. Kuperman suggests that this demonization of Gaddafi, which was used to justify the intervention, ended up discouraging efforts to accept a ceasefire and negotiated settlement, turning a humanitarian intervention into a dedicated regime change.[278][undue weight? – discuss]

Moreover, criticisms have been made on the way the operation was led. According to Michael Kometer and Stephen E. Wright in Focus stratégique, the outcome of the Libyan intervention was reached by default rather than by design. It appears that there was an important lack of consistent political guidance caused particularly by the vagueness of the UN mandate and the ambiguous consensus among the NATO-led coalition. This lack of clear political guidance was translated into an incoherent military planning on the operational level. Such a gap may impact the future NATO's operations that will probably face trust issues.[279][undue weight? – discuss]

Costs

| Funds spent by Foreign Powers on War in Libya. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Country | Funds Spent | By | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | US$336–1,500 million | September 2011 (estimate)[280][281] | |||||||||||||||||

| United States | US$896–1,100 million | October 2011[282][283][284][285][286] | |||||||||||||||||

| Italy | €700 million EUR | October 2011[287] | |||||||||||||||||

| France | €450 million EUR | September 2011[288][289] | |||||||||||||||||

| Turkey | US$300 million | July 2011[290] | |||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | €120 million EUR | November 2011[291] | |||||||||||||||||

| Belgium | €58 million EUR | October 2011[292] | |||||||||||||||||

| Spain | €50 million EUR | September 2011[293] | |||||||||||||||||

| Sweden | US$50 million | October 2011[294] | |||||||||||||||||

| Canada | $50 million CAD incremental Over $347.5 million CAD total |

October 2011[295] | |||||||||||||||||

On 22 March 2011, BBC News presented a breakdown of the likely costs to the UK of the mission.[296] Journalist Francis Tusa, editor of Defence Analysis, estimated that flying a Tornado GR4 would cost about £35,000 an hour (c. US$48,000), so the cost of patrolling one sector of Libyan airspace would be £2M–3M (US$2.75M–4.13M) per day. Conventional airborne missiles would cost £800,000 each and Tomahawk cruise missiles £750,000 each. Professor Malcolm Charmers of the Royal United Services Institute similarly suggested that a single cruise missile would cost about £500,000, while a single Tornado sortie would cost about £30,000 in fuel alone. If a Tornado was downed the replacement cost would be upwards of £50m. By 22 March the US and UK had already fired more than 110 cruise missiles. UK Chancellor George Osborne had said that the MoD estimate of the operation cost was "tens rather than hundreds of millions". On 4 April Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Dalton said that the RAF was planning to continue operations over Libya for at least six months.[297]

The total number of sorties flown by NATO numbered more than 26,000, an average of 120 sorties per day. 42% of the sorties were strike sorties, which damaged or destroyed approximately 6,000 military targets. At its peak, the operation involved more than 8,000 servicemen and women, 21 NATO ships in the Mediterranean and more than 250 aircraft of all types. By the end of the operation, NATO had conducted over 3,000 hailings at sea and almost 300 boardings for inspection, with 11 vessels denied transit to their next port of call.[298] Eight NATO and two non-NATO countries flew strike sorties. Of these, Denmark, Canada, and Norway together were responsible for 31%,[299] the United States was responsible for 16%, Italy 10%, France 33%, Britain 21%, and Belgium, Qatar, and the UAE the remainder.[300]

Aftermath

Since the end of the war, which overthrew Gaddafi, there has been violence involving various militias and the new state security forces.[301][302] The violence has escalated into the Second Libyan Civil War. Critics described the military intervention as "disastrous" and accused it of destabilizing North Africa, leading to the rise of Islamic extremist groups in the region.[303][245] Libya became what many scholars described as a failed state — a state that has disintegrated to a point where the government no longer performs its function properly.[304][305][306]

Libya has become the main exit for migrants trying to get to Europe.[307] In September 2015, South African President Jacob Zuma said that "consistent and systematic bombing by NATO forces undermined the security and caused conflicts that are continuing in Libya and neighbouring countries ... It was the actions taken, the bombarding of Libya and killing of its leader, that opened the flood gates."[308]

In a 2016 interview with Fox News, U.S. President Barack Obama stated that the "worst mistake" of his presidency was "probably failing to plan for the day after what I think was the right thing to do in intervening in Libya."[309][310] Obama also acknowledged there had been issues with following up the conflict planning, commenting in a 2016 interview with The Atlantic magazine that British Prime Minister David Cameron had allowed himself to be "distracted by a range of other things".[311][312][313]

Notes

- ^ Enforcing UNSC Resolution 1973

See also

- Aftermath of the Libyan Civil War

- European migrant crisis

- Second Libyan Civil War

- Killing of Muammar Gaddafi

- Protests against the 2011 military intervention in Libya

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973

- US military campaign in Libya against ISIS

- Bombing of Libya, code-named Operation El Dorado Canyon, response to 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing

- Iraqi no-fly zones, two similar operations carried out over Iraq:

- Operation Deny Flight, similar operation carried out during the Bosnian War (1992–1995)

- Ouadi Doum air raid, 1986 French air raid on Libyan airbase in Chad

- 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War

References

- ^ Blomfield, Adrian (23 February 2011). "Libya: Foreign Mercenaries Terrorising Citizens". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ HUMA KHAN; HELEN ZHANG (22 February 2011). "Moammar Gadhafi's Private Mercenary Army 'Knows One Thing: To Kill'". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Meo, Nick (27 February 2011). "African Mercenaries in Libya Nervously Await Their Fate". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Belarus Suspected of Supplying Arms, Mercenaries - TIME". Archived from the original on 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Algeria May have Violated UN Resolution by Providing Weapons to Libya, US State Dept". Archived from the original on 29 July 2011.

- ^ "North Korea and Libya: friendship through artillery | NK News". NK News – North Korea News. 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Nato chief Rasmussen 'proud' as Libya mission ends". BBC News. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Muammar Gaddafi Killed as Sirte Falls". Al Jazeera. 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Gaddafi's son Saif al-Islam captured in Libya". BBC News. 19 November 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Operation Unified Protector Final Mission Stats" (PDF). NATO. 2 November 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "The North African Military Balance", Anthony H. Cordesman, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 29 March 2005, p. 32, p. 36

- ^ a b M. Cherif Bassiouni, "Libya: From Repression to Revolution", 13 December 2013, p. 138

- ^ a b c d "Libya Conflict: Nato Loses Drone Helicopter". BBC News. 21 June 2011. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Three Dutch Marines Captured During Rescue in Libya". BBC News. 3 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "US Crew Rescued after Libya Crash". BBC News. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "UAE Fighter Jet Veers Off Runway at Base in Italy: Report". Zawya/AFP. 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ "NATO: Gadhafi Forces Caught Mining Misrata Port". USA Today. Brussels. Associated Press. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Unacknowledged Deaths: Civilian Casualties in NATOs Air Campaign in Libya". Human Rights Watch. 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ "Vatican: Airstrikes Killed 40 Civilians in Tripoli". The Jerusalem Post. 31 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Imhof, Oliver (18 March 2021). "Ten years after the Libyan revolution, victims wait for justice". Airwars. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "All Belligerents in Libya, 2011".

- ^ "Coalition Targets Gadhafi Compound". CNN. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ a b c "Security Council Approves 'No-Fly Zone' over Libya, Authorizing 'All Necessary Measures' to Protect Civilians, by Vote of 10 in Favour with 5 Abstentions". United Nations. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Libya Live Blog – March 19". Al Jazeera. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: US, UK and France attack Gaddafi forces". BBC News. 20 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b "French Fighter Jets Deployed over Libya". CNN. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "France Uses Unexplosive Bombs in Libya: Spokesman". Xinhua News Agency. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Gibson, Ginger (8 April 2011). "Polled N.J. Voters Back Obama's Decision To Establish No-Fly Zone in Libya". The Star-Ledger. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (24 August 2011). "Nato will not put troops on ground in Libya". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "British and French special forces with Libya rebels | August 2011 news defense army military industry UK | Military army defense industry news year 2011". www.armyrecognition.com. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Anthony H. Cordesman (29 March 2005). "The North African Military Balance" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies. p. 32, p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Gunfire, Explosions Heard in Tripoli". CNN. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Horace Campbell (2013). NATO's Failure in Libya: Lessons for Africa. African Books Collective. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7983-0343-9.

- ^ "Qatar, several EU states up for Libya action: diplomat". EUbusiness.com. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Paris Summit Talks To Launch Military Action in Libya". European Jewish Press. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: President Obama Gives Gaddafi Ultimatum". BBC News. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: RAF Jets Join Attack on Air Defence Systems". WalesOnline. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Batty, David (19 March 2011). "Military Action Begins Against Libya". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Norington, Brad (23 March 2011). "Deal Puts NATO at Head of Libyan Operation". The Australian. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Traynor, Ian; Watt, Nicholas (23 March 2011). "Libya No-Fly Zone Leadership Squabbles Continue Within Nato". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Brunnstrom, David; Taylor, Paul (24 March 2011). "NATO reaches agreement on Libya command (Google cached page)". National Post. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "NATO to police Libya no-fly zone". Al Jazeera. 24 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Burns, Robert; Werner, Erica (24 March 2011). "NATO Agrees To Take Over Command of Libya No-Fly Zone, U.S. Likely To Remain in Charge of Brunt of Combat". Huffington Post. Washington D.C. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "Libya's Mustafa Abdul Jalil asks Nato to stay longer". BBC. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "UN Security Council votes to end Libya operations". BBC News. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "All Belligerents in Libya, 2011". airwars.org. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Libyan Ambassador to U.N. Urges International Community To Stop Genocide". Global Arab Network. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Rebel Leader Calls for 'Immediate Action' on No-Fly Zone". CNN. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b McGreal, Chris (12 March 2011). "Gaddafi's Army Will Kill Half a Million, Warn Libyan Rebels". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Thousands of Libyan Women March for 'No-Fly Zone'". NOW Lebanon. Agence France-Presse. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ a b Donnet, Pierre-Antoine (7 March 2011). "Britain, France Ready Libya No-Fly Zone Resolution". Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ a b Macdonald, Alistair (28 February 2011). "Cameron Doesn't Rule Out Military Force for Libya". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Denslow, James (16 March 2011). "Lebanon's Role in a U.N. Security Council Resolution Against Libya Is Evidence of Unfinished Business Between the Two States". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: UK Forces Prepare after UN No-Fly Zone Vote". BBC News. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen; Lynch, Colum (17 March 2011). "Europeans Say Intervention in Libya Possible Within Hours of U.N. Vote". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b c "Arab States Seek Libya No-Fly Zone". Al Jazeera. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b Perry, Tom (12 March 2011). "Arab League Calls for Libya No-Fly Zone-State TV". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Breaking: Arab League Calls on U.N. To Impose No Fly Zone on Libya". LibyaFeb17.com. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b Mardell, Mark (17 March 2011). "Libya: UN Backs Action Against Colonel Gaddafi". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ a b "U.N. Security Council Approves No-Fly Zone over Libya". CNN. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "As It Happened: Libya Uprising February 25". The Times. 25 April 2011. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ "In Swift, Decisive Action, Security Council Imposes Tough Measures on Libyan Regime, Adopting Resolution 1970 in Wake of Crackdown on Protesters". United Nations. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Canada sending warship to Libya". Canada.com. 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ Ibbitson, John; Leblanc, Daniel (21 October 2011). "Canada turns commitment into clout in Libya". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Marquand, Robert (28 March 2011). "How a Philosopher Swayed France's Response on Libya". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ Escobar, Pepe (2 April 2011). "Exposed: The US-Saudi Libya Deal". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "'Clock Is Ticking' on Libya, Cameron Warns". The Times. 15 March 2011. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Denselow, James (16 March 2011). "Libya and Lebanon: A Troubled Relationship". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "Security Council Authorizes 'All Necessary Measures' To Protect Civilians in Libya". U.N. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "U.N. Security Council Resolution on Libya – Full Text". The Guardian. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "Libya Declares Ceasefire But Fighting Goes On". Al Jazeera. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Rebels, West Wary of Libyan Ceasefire". Deutsche Welle. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Foreign Minister Announces Immediate Ceasefire". BBC News. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Amara, Tarek; Karouny, Mariam (18 March 2011). "Gaddafi Forces Shell West Libya's Misrata, 25 Dead". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Gaddafi Forces Attacking Rebel-Held Benghazi". BBC News. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi Forces Encroaching on Benghazi". Al Jazeera. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Remarks by the President on the Situation in Libya". whitehouse.gov. 18 March 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2020 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Inside the White House-Congress Meeting on Libya". Foreign Policy. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Jonathan Marcus (19 March 2011). "Libya: French plane fires on military vehicle". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Text of a Letter from the President to the Speak of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate" (PDF). C-SPAN. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011.

- ^ Traynor, Ian; Watt, Nicholas (23 March 2011). "Libya No-Fly Zone Leadership Squabbles Continue within Nato – Turkey Calls for an Alliance-Led Campaign To Limit Operations While France Seeks a Broader 'Coalition of the Willing'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ Traynor, Ian; Watt, Nicholas (24 March 2011). "Libya: Nato To Control No-Fly Zone after France Gives Way to Turkey". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ Newton, Paula (25 March 2011). "NATO Considers Broader Role in Libya". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "NATO No-Fly Zone over Libya Operation Unified Protector" (PDF). NATO. 25 March 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Weekly Address: President Obama Says the Mission in Libya is Succeeding". whitehouse.gov. 26 March 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2020 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Remarks by the President in Address to the Nation on Libya". whitehouse.gov. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Clinton on Qaddafi: "We came, we saw, he died"". www.cbsnews.com. 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Borger, Julian (8 March 2011). "Nato weighs Libya no-fly zone options". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: UK and French No-Fly Zone Plan Gathers Pace". BBC News. 8 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Mulling Military Options in Libya". CNN. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Nato Takes Over Libya No-Fly Zone". BBC News. 24 March 2011. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Traynor, Ian; Watt, Nicholas (24 March 2011). "Nato To Oversee Libya Campaign after France and Turkey Strike Deal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ "Canadian to lead NATO's Libya mission". CBC News. 25 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Muammar Gaddafi's body to undergo post-mortem". BBC. 22 October 2011. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Машева, Гергана (21 March 2011). "Пращаме "Дръзки" да патрулира край Либия". Dir.bg. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Bulgaria's Drazki Frigate Ready to Set Sail for Libya". Standart. 23 March 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Bulgarian Frigate on Its Way to Libyan Coast". The Sofia Echo. 30 March 2011. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Bulgarian Frigate Sets Out for Libya Embargo Operation 27 April". Sofia News Agency. 21 April 2011. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "Canadian Warship En Route, JTF2 Sent to Libya". Ottawa Citizen. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Harper confirme l'envoi de sept CF-18" (in French). TVA Nouvelles. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Les CF-18 partent pour la Méditerranée". Le Journal de Montréal (in French). 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Canada Will Fight To Protect Libyan Civilians: Harper". CTV News. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Operation Mobile". Canadian Expeditionary Force Command. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ "Denmark To Send Squadron on Libya Op". Politiken. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Danish F-16s drop their first bombs on Libya". Flight International. 23 March 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Mission update 1. April. Forsvaret.dk (11 October 2011). Retrieved 16 August 2013. Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Norske fly bomber mest i Libya". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 29 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ (in Danish) Danske piloter lukkede Libyen-togt – International Archived 7 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Jyllands-posten.dk. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ Mission update 31. oktober. Forsvaret.dk. Retrieved 16 August 2013. Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Libye: début des opérations aériennes françaises" (in French). French Ministry of Defense. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b c "French Aircraft Carrier To Join Libya Effort from Greece". Expatica Belgium. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Tran, Pierre (19 March 2011). "France Deploys About 20 Aircraft to Enforce Libya No-Fly Zone". DefenseNews. Retrieved 19 March 2011.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Greece Will Not Be Neutral on Libya, PM Says". ekathimerini.com. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: the LPD Mistral relives the Tonnerre". www.defense.gouv.fr. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Melvin, Don (23 May 2011). "French Official: Helicopters Being Sent to Libya". Associated Press.

- ^ "L'Opération Harmattan en chiffres". 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Libye: point de situation n° 50 - bilan de l'opération Unified Protector". Defense.gouv.fr. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Greek Defence Ministry: No Participation in Operations Outside the NATO". Keep Talking Greece. 20 March 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "ΣΚΑΪ Player TV — ΣΚΑΪ (www.skai.gr)" Πρώτη Γραμμή – ΣΚΑΪ (in Greek). skai.gr. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Makris, A. (21 March 2011). "Greece's Participation in Operation against Libya Costs 1 Million Euros Daily". Greekreporter.com. Greek Reporter. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2011.