Jami

Mawlanā Jami | |

|---|---|

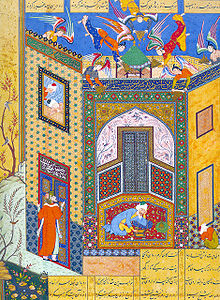

Jami, Artwork of Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād | |

| Mystic, Spiritual Poet, Historian, Theologian | |

| Born | 7 November 1414[1] Jam, Khorasan, Timurid Empire[2] |

| Died | 9 November 1492 (aged 78) Herat, Khorasan, Timurid Empire |

| Venerated in | Islam |

| Influences | Muhammad, Khwaja Abdullah Ansari , Rumi, Ibn Arabi |

Tradition or genre | Sufi poetry |

Nūr ad-Dīn 'Abd ar-Rahmān Jāmī (Template:Lang-fa), also known as Mawlanā Nūr al-Dīn 'Abd al-Rahmān or Abd-Al-Rahmān Nur-Al-Din Muhammad Dashti, or simply as Jami or Djāmī and in Turkey as Molla Cami (7 November 1414 – 9 November 1492), was a Persian[3][4] Sunni[5] poet who is known for his achievements as a prolific scholar and writer of mystical Sufi literature. He was primarily a prominent poet-theologian of the school of Ibn Arabi and a Khwājagānī Sũfī, recognized for his eloquence and for his analysis of the metaphysics of mercy.[6][7] His most famous poetic works are Haft Awrang, Tuhfat al-Ahrar, Layla wa Majnun, Fatihat al-Shabab, Lawa'ih, Al-Durrah al-Fakhirah. Jami belonged to the Naqshbandi Sufi order.[8]

Biography

Jami was born in Jam,[2] (modern Ghor Province, Afghanistan) in Khorasan.[9] Previously his father Nizām al-Dīn Ahmad b. Shams al-Dīn Muhammad had come from Dasht, a small town in the district of Isfahan.[9] A few years after his birth, his family migrated to Herat, where he was able to study Peripateticism, mathematics, Persian literature, natural sciences, Arabic language, logic, rhetoric and Islamic philosophy at the Nizamiyyah University.[6] His father, also a Sufi, became his first teacher and mentor.[6] While in Herat, Jami held an important position at the Timurid court, involved in the era's politics, economics, philosophy and religious life.[6] Jami was a Sunni Muslim.[5]

Because his father was from Dasht, Jami's early pen name was Dashti, but later, he chose to use Jami because of two reasons he later mentioned in a poem:

مولدم جام و رشحهء قلمم

جرعهء جام شیخ الاسلامی است

لاجرم در جریدهء اشعار

به دو معنی تخلصم جامی است

My birthplace is Jam, and my pen

Has drunk from (knowledge of) Sheikh-ul-Islam (Ahmad) Jam

Hence in the books of poetry

My pen name is Jami for these two reasons.

Jami was a mentor and friend of the famous Turkic poet Alisher Navoi, as evidenced by his poems:

او که یک ترک بود و من تاجیک،

هردو داشتیم خویشی نزدیک.

U ki yak Turk bud va man Tajik

Hardu doshtim kheshii nazdik

Though he was a Turk, and I am Tajik,

We were close to each other.[10]

Afterwards, he went to Samarkand, the most important center of scientific studies in the Muslim world and completed his studies there. He embarked on a pilgrimage that greatly enhanced his reputation and further solidified his importance through the Persian world.[9] Jami had a brother called Molana Mohammad, who was, apparently a learned man and a master in music, and Jami has a poem lamenting his death. Jami fathered four sons, but three of them died before reaching their first year.[11] The surviving son was called Zia-ol-din Yusef and Jami wrote his Baharestan for this son.

At the end of his life he was living in Herat. His epitaph reads "When your face is hidden from me, like the moon hidden on a dark night, I shed stars of tears and yet my night remains dark in spite of all those shining stars."[12] There is a variety of dates regarding his death, but consistently most state it was in November 1492. Although, the actual date of his death is somewhat unknown the year of his death marks an end of both his greater poetry and contribution, but also a pivotal year of political changed where Spain was no longer inhabited by the Arabs after 781 years.[13] His funeral was conducted by the prince of Herat and attended by great numbers of people demonstrating his profound impact.[11]

Teachings and Sufism

In his role as Sufi shaykh, which began in 1453 , Jami expounded a number of teachings regarding following the Sufi path. He created a distinction between two types of Sufi's, now referred to as the "prophetic" and the "mystic" spirit.[14] Jami is known for both his extreme piety and mysticism.[6][7] He remained a staunch Sunni on his path toward Sufism and developed images of earthly love and its employment to depict spiritual passion of the seeker of God.[6][15] He began to take an interest in Sufism at an earlier age when he received a blessing by a principal associate Khwaja Mohammad Parsa who came through town.[16] From there he sought guidance from Sa'd-alDin Kasgari based on a dream where he was told to take God and become his companion.[17] Jami followed Kasagari and the two became tied together upon Jami's marriage to Kasgari's granddaughter.[16] He was known for his commitment to God and his desire for separation from the world to become closer to God often causing him to forget social normalities.[16]

After his re-emergence into the social world he became involved in a broad range of social, intellectual and political actives in the cultural center of Herat.[16] He was engaged in the school of Ibn Arabi, greatly enriching, analyzing, and also changing the school or Ibn Arabi. Jami continued to grow in further understanding of God through miraculous visions and feats, hoping to achieve a great awareness of God in the company of one blessed by Him.[16] He believed there were three goals to achieve "permanent presence with God" through ceaselessness and silence, being unaware of one's earthly state, and a constant state of a spiritual guide.[18] Jami wrote about his feeling that God was everywhere and inherently in everything.[14] He also defined key terms related to Sufism including the meaning of sainthood, the saint, the difference between the Sufi and the one still striving on the path, the seekers of blame, various levels of tawhid, and the charismatic feats of the saints.[18] Oftentimes Jami's methodology did not follow the school of Ibn Arabi, like in the issue of mutual dependence between God and his creatures Jami stated "We and Thou are not separate from each other, but we need Thee, whereas Thou dost not need us."

Jami created an all-embracing unity emphasized in a unity with the lover, beloved, and the love one, removing the belief that they are separated.[14] Jami was in many ways influenced by various predecessors and current Sufi's, incorporating their ideas into his own and developing them further, creating an entirely new concept. In his view, love for the Prophet Mohammad was the fundamental stepping stone for starting on the spiritual journey. Jami served as a master to several followers and to one student who asked to be his pupil who claimed never to have loved anyone, he said, "Go and love first, then come to me and I will show you the way."[18][19] For several generations, Jami had a group of followers representing his knowledge and impact. Jami continues to be known for not only his poetry, but his learned and spiritual traditions of the Persian speaking world.[18] In analyzing Jami's work greatest contribution may have been his analysis and discussion of God's mercy towards man, redefining the way previous texts were interpreted.

Works

Jami wrote approximately eighty-seven books and letters, some of which have been translated into English. His works range from prose to poetry, and from the mundane to the religious. He has also written works of history and science. As well, he often comments on the work of previous and current theologians, philosophers and Sufi's.[6] In Herat, his manual of irrigation design included advanced drawings and calculations and is still a key reference for the irrigation department.[20] His poetry has been inspired by the ghazals of Hafiz, and his famous and beautiful divan Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) is, by his own admission, influenced by the works of Nizami. The Haft Awrang also known as the long masnavis or mathnawis are a collection of seven poems.[21] Each poem discusses a different story such as the Salaman va Absal that tells the story of a carnal attraction of a prince for his wet-nurse.[22] Throughout Jami uses allegorical symbolism within the tale to depict the key stages of the Sufi path such as repentance and expose philosophical, religious, or ethical questions.[11][21] Each of the allegorical symbols has a meaning highlighting knowledge and intellect, particularly of God. This story reflects Jamī's idea of the Sufi-king as the ideal medieval Islamic ruler to repent and embark upon the Sufi path to realize his rank as God's 'true' vicegerent and become closer to God.[21] As well, Jami is known for his three collections of lyric poems that range from his youth towards the end of his life called the Fatihat al-shabab (The Beginning of Youth), Wasitat al-'ikd (The Central Pearl in the Necklace), and Khatimat al-hayat (The conclusion of Life).[11] Throughout Jami's work references to Sufism and the Sufi emerge as being key topics. One of his most profound ideas was the mystical and philosophical explanations of the nature of divine mercy, which was a result of his commentary to other works.[6]

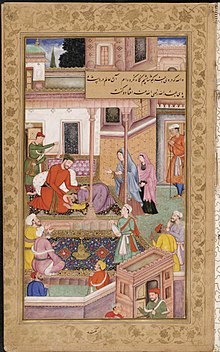

Artwork

Jami is also known for his poetry influencing and being included with Persian paintings that depict Persian history through manuscript paintings. Most of his own literature included illustrations that was not yet common for literature. The deep poetry Jami provides, is usually accompanied with enriched paintings reflecting the complexity of Jami's work and Persian culture.[23]

Impact of Jami's works

Jami worked within the Tīmūrid court of Herat helping to serve as an interpreter and communicator.[6] His poetry reflected Persian culture and was popular through Islamic East, Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.[6] His poetry addressed popular ideas that led to Sufi's and non-Sufi's interest in his work.[14] He was known not only for his poetry, but his theological works and commentary of on culture.[6] His work was used in several schools from Samarqand to Istanbul to Khayrābād in Persia as well as in the Mughal Empire.[6] For centuries Jami was known for his poetry and profound knowledge. In the last half-century Jami has begun to be neglected and his works forgotten, which reflects an overarching issue in the lack of research of Islamic and Persian studies.[6]

Divan of Jami

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

Among his works are:

- Baharestan (Abode of Spring) Modeled upon the Gulestan of Saadi

- Diwanha-ye Sehganeh (Triplet Divans)

- Al-Fawaed-Uz-Ziya'iya.[24] A commentary on Ibn al-Hajib's treatise on Arab grammar Al-Kafiya. This commentary has been a staple of Ottoman Madrasas' curricula under its author's name Molla Cami.[25]

- Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) His major poetical work. The fifth of the seven stories is his acclaimed "Yusuf and Zulaykha", which tells the story of Joseph and Potiphar's wife based on the Quran.

- Jame -esokanan-e Kaja Parsa

- Lawa'ih A treatise on Sufism (Shafts of Light)

- Nafahat al-Uns (Breaths of Fellowship) Biographies of the Sufi Saints

- Resala-ye manasek-e hajj

- Resala-ye musiqi

- Resala-ye tariq-e Kvajagan

- Resala-ye sarayet-e dekr

- Resala-ye so al o jawab-e Hendustan

- Sara-e hadit-e Abi Zarrin al-Aqili

- Sar-rešta-yetariqu-e Kājagān (The Quintessence of the Path of the Masters)

- Shawahidal-nubuwwa (Distinctive Signs of Prophecy)

- Tajnīs 'al-luġāt (Homonymy/Punning of Languages) A lexicographical work containing homonymous Persian and Arabic lemmata.[26]

- Tuhfat al-ahrar (The Gift to the Noble)[27]

Along with his works are his contributions to previous works and works that have been created in response to his new ideas.[15]

See also

References

- ^ Jami: Ali Asghar Hikmat, Urdu Translation Arif Naushahi, p. 124

- ^ a b "Nour o-Din Abdorrahman Jami". Iran Chamber Society. Retrieved 2013-04-03.

- ^ "JĀMI – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

JĀMI, ʿABD-AL-RAḤMĀN NUR-AL-DIN b. Neẓām-al-Din Aḥmad-e Dašti, Persian poet, scholar, and Sufi of the 15th century

- ^ Culture and Circulation: Literature in Motion in Early Modern India. BRILL. 2014. ISBN 9789004264489.

works of the Persian polymath ʿAbd al-RahmanJami (1414–1492) under the auspices of the Neubauer Collegium for ...

- ^ a b Hamid Dabashi, The World of Persian Literary Humanism, Harvard University Press, p. 150,

In addition to being a leading Sufi, Jami was also a devout Sunni, quite critical of Shi'ism..."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Rizvi, Sajjad. "The Existential Breath of al-rahman and the Munificent Grace of al-rahim: The Tafsir Surat al-Fatiha of Jami and the School of Ibn Arabi". Journal of Qur'anic Studies.

- ^ a b Williams, John (1961). Islam. New York: George Braziller.

- ^ Hamid Dabashi, The World of Persian Literary Humanism, Harvard University Press, p. 150

- ^ a b c Losensky, Paul (23 June 2008). "JĀMI". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Abdullaev K.N. From Xinjiang to Khorasan. Dushanbe. 2009, p.70

- ^ a b c d Huart, Cl.; Masse, H. "Djami, Mawlana Nur al-Din 'Abd ah-Rahman". Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- ^ Ahmed, Rashid (2001). Taliban, p. 40. Yale University Press.

- ^ Machatsche, Roland (1996). The Basics:2 Islam. Trinity Press.

- ^ a b c d Schimmel, AnnMarie (1975). Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Capital Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ a b Rahman, Fazlur (1966). Islam. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- ^ a b c d e Algar, Hamid (June 2008). "Jami and Sufism". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Kia, Chad (June 2008). "Jami and Sufism". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ a b c d Algar, Hamid (23 June 2008). "Jami and Sufism". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ "VOLUME X_3_4". Wahiduddin.net. 2005-10-18. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ^ Chokkakula, Srinivas (2009). "Interrogating Irrigation Inequities: Canal Irrigation Systems in Injil District, Herat". Case Study Series. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. p. 12.

- ^ a b c Lingwood, Chad (March 2011). "Jami's Salaman va Absal: Political Statements and Mystical Advice Addressed to the Aq Qoyunlu Court of Sultan Ya'qub (d. 896/1490)". Iranian Studies. 44 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1080/00210862.2011.541687.

- ^ Lingwood, Chad (March 2011). "Jami's Salaman va Absal: Political Statements and Mystical Advice Addressed to the Aq Qoyunlu Court of Sultan Ya'qub (d. 896/1490)". Iranian Studies. 44 (2): 174–191. doi:10.1080/00210862.2011.541687.

- ^ Kia, Chad (23 June 2008). "Jami and Persian Art". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ "شـرح مـلا جـامـي – Sharh Mulla Jami". Arabicbookshop.net. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ^ Okumuş, Ö. (1993). Molla Cami. In İslam Ansiklopedisi (Vol. 7, pp. 94–99). Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı.

- ^ Shīrānī, 6.

- ^ "Tuhfat-ul-Ahrar by Maulana Jami (Persian) : Maulana Abdul Rahman Jami : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Archive.org. 2001-03-10. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

Sources

- E.G. Browne. Literary History of Persia. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and twenty-five years in the writing). 1998. ISBN 978-0-7007-0406-4

- Jan Rypka, History of Iranian Literature. Reidel Publishing Company. 1968 OCLC 460598 ISBN 978-90-277-0143-5

- Ḥāfiż Mahmūd Shīrānī. "Dībācha-ye awwal [First Preface]". In Ḥifż ul-Lisān [a.k.a. Ḳhāliq Bārī], edited by Ḥāfiż Mahmūd Shīrānī. Delhi: Anjumman-e Taraqqi-e Urdū, 1944.

- Aftandil Erkinov A. "La querelle sur l`ancien et le nouveau dans les formes litteraires traditionnelles. Remarques sur les positions de Jâmi et de Navâ`i". Annali del`Istituto Universitario Orientale. 59, (Napoli), 1999, pp. 18–37.

- Aftandil Erkinov. "Manuscripts of the works by classical Persian authors (Hāfiz, Jāmī, Bīdil): Quantitative Analysis of 17th–19th c. Central Asian Copies". Iran: Questions et connaissances. Actes du IVe Congrès Européen des études iraniennes organisé par la Societas Iranologica Europaea, Paris, 6–10 Septembre 1999. vol. II: Périodes médiévale et moderne. [Cahiers de Studia Iranica. 26], M.Szuppe (ed.). Association pour l`avancement des études iraniennes-Peeters Press. Paris-Leiden, 2002, pp. 213–228.

- Jami. Flashes of Light: A Treatise on Sufism. Golden Elixir Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9843082-2-4 (ebook)

For Further Reading:

- R. M. Chopra, "Great Poets of Classical Persian", Sparrow Publication, Kolkata, 2014, (ISBN 978-81-89140-75-5)

External links

- Jami on Iran Chamber Society Website

- Jami's Yusuf and Zulaikha: A Study in the Method of Appropriation of Sacred Text

- Jami's Salaman and Absal as Translated by Edward Fitzgerald. 1904

- Persian deewan of Jami Uploaded by Javed Hussen

- Online books by Jami – maktabah.org

- Works by Jami at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jami at the Internet Archive