Cyclopes: Difference between revisions

Tide rolls (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 205.202.40.248 to last revision by ClueBot (HG) |

|||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Another possible origin for the Cyclops legend, advanced by the paleontologist [[Othenio Abel]] in 1914,<ref>Abel's surmise is noted by Adrienne Mayor, ''The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times'' (Princeton University Press) 2000.</ref> is the prehistoric [[dwarf elephant]] skulls – about twice the size of a human skull – that may have been found by the Greeks on [[Crete]] and [[Sicily]]. Abel suggested that the large, central nasal cavity (for the trunk) in the skull might have been interpreted as a large single eye-socket.<ref>The smaller, actual eye-sockets are on the sides and, being very shallow, were hardly noticeable as such</ref> Given the inexperience of the locals with living [[elephant]]s, they were unlikely to recognize the skull for what it actually was.<ref>[http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~loxias/cyclops02.htm "Meet the original Cyclops"]. Retrieved 18 May 2007.</ref> |

Another possible origin for the Cyclops legend, advanced by the paleontologist [[Othenio Abel]] in 1914,<ref>Abel's surmise is noted by Adrienne Mayor, ''The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times'' (Princeton University Press) 2000.</ref> is the prehistoric [[dwarf elephant]] skulls – about twice the size of a human skull – that may have been found by the Greeks on [[Crete]] and [[Sicily]]. Abel suggested that the large, central nasal cavity (for the trunk) in the skull might have been interpreted as a large single eye-socket.<ref>The smaller, actual eye-sockets are on the sides and, being very shallow, were hardly noticeable as such</ref> Given the inexperience of the locals with living [[elephant]]s, they were unlikely to recognize the skull for what it actually was.<ref>[http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~loxias/cyclops02.htm "Meet the original Cyclops"]. Retrieved 18 May 2007.</ref> |

||

''[[Veratrum album]]'', or [[white hellebore]], an herbal medicine described by [[Hippocrates]] before 400 BC,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Hellebore|title=1911 Encyclopedia Brittanica, citing Codronchius (Comm.... ''de elleb.'', 1610), Castellus (''De helleb. epistola'', 1622), Horace (Sat. ii. 3.80-83, Ep. ad Pis. 300).}}</ref> contains the alkaloids [[cyclopamine]] and [[jervine]], which are [[teratogen]]s capable of causing [[cyclopia]] (holoprosencephaly). Students of [[teratology]] have raised the possibility of a link between this developmental deformity and the myth sharing its name.<ref>Armand Marie Leroi, ''Mutants; On the Form, Varieties and Errors of the Human Body'', 2005:68.</ref> |

''[[Veratrum album]]'', or [[white hellebore]], an herbal medicine described by [[Hippocrates]] before 400 BC,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Hellebore|title=1911 Encyclopedia Brittanica, citing Codronchius (Comm.... ''de elleb.'', 1610), Castellus (''De helleb. epistola'', 1622), Horace (Sat. ii. 3.80-83, Ep. ad Pis. 300).}}</ref> contains the alkaloids [[cyclopamine]] and [[jervine]], which are [[teratogen]]s capable of causing [[cyclopia]] (holoprosencephaly). Students of [[teratology]] have raised the possibility of a link between this developmental deformity and the myth sharing its name.<ref>Armand Marie Leroi, ''Mutants; On the Form, Varieties and Errors of the Human Body'', 2005:68.</ref>cyclopus wants my dick so i gave it to him |

||

=="Cyclopean" walls== |

=="Cyclopean" walls== |

||

Revision as of 13:37, 7 April 2009

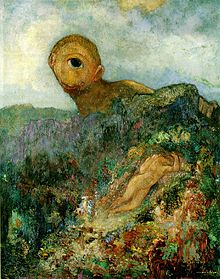

In Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, a cyclops (Template:PronEng; Template:Lang-el), is a member of a primordial race of giants, each with a single eye in the middle of its forehead. The classical plural is cyclopes (pronounced /saɪˈkloʊpiːz/; Template:Lang-el), though the conventional plural cyclopses is also used in English. The name is widely thought to mean "circle-eyed".[1]

Hesiod described one group of cyclopes and the epic poet Homer described another, though other accounts have also been written by the playwright Euripides, poet Theocritus and Roman epic poet Virgil. In Hesiod's Theogony, Zeus releases three Cyclopes, the sons of Uranus and Gaia, from the dark pit of Tartarus. They provide Zeus' thunderbolt, Hades' helmet of invisibility, and Poseidon's trident, and the gods use these weapons to defeat the Titans. In a famous episode of Homer's Odyssey, the hero Odysseus encounters the Cyclops Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon and a nereid (Thoosa), who lives with his fellow Cyclopes in a distant country. The connection between the two groups has been debated in antiquity and by modern scholars.[2] It is upon Homer's account that Euripides and Virgil based their accounts of the mythical creatures.

Accounts of the Cyclopes

Various ancient Greek and Roman authors wrote about the cyclopes. Hesiod described them as three brothers who were primordial giants. All the other sources of literature about the cyclopes describe the cyclops Polyphemus, who lived upon an island populated by the creatures.

Hesiod

In the Theogony by Hesiod, the Cyclopes – Arges,[3] Brontes, and Steropes – were the primordial sons of Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth) and brothers of the Hecatonchires. They were giants with a single eye in the middle of their forehead and a foul disposition. According to Hesiod, they were strong, stubborn, and "abrupt of emotion". Collectively they eventually became synonyms for brute strength and power, and their name was invoked in connection with massive masonry. They were often pictured at their forge.

Uranus, fearing their strength, locked them in Tartarus. Cronus, another son of Uranus and Gaia, later freed the Cyclopes, along with the Hecatonchires, after he had overthrown Uranus. Cronus then placed them back in Tartarus, where they remained, guarded by the female dragon Campe, until freed by Zeus. They fashioned thunderbolts for Zeus to use as weapons, and helped him overthrow Cronus and the other Titans. The thunderbolts, which became Zeus' main weapons, were forged by all three Cyclopes, in that Arges added brightness, Brontes added thunder, and Steropes added lightning.

These Cyclopes also created Poseidon's trident, Artemis's bow and arrows of moonlight, Apollo's bow and arrows of sun rays, and the helmet of darkness that Hades gave to Perseus on his quest to kill Medusa. According to a hymn of Callimachus,[4] they were Hephaestus' helpers at the forge. The Cyclopes were said to have built the "cyclopean" fortifications at Tiryns and Mycenae in the Peloponnese. The noises proceeding from the heart of volcanoes were attributed to their operations.

According to Alcestis, Apollo killed the Cyclopes, in retaliation for Asclepius' murder at the hands of Zeus. According to Euripides' play Alkestis, Apollo was then forced into the servitude of Admetus for one year. Zeus later returned Asclepius and the Cyclopes from Hades.

Theocritus

The Sicilian Greek poet Theocritus wrote two poems circa 275 BC concerning Polyphemus' desire for Galatea, a sea nymph. When Galatea instead married Acis, a Sicilian mortal, a jealous Polyphemus killed him with a boulder. Galatea turned Acis' blood into a river of the same name in Sicily.

Virgil

Virgil, the Roman epic poet, wrote, in book three of The Aeneid, of how Aeneas and his crew landed on the island of the cyclopes after escaping from Troy at the end of the Trojan War. Aeneas and his crew land on the island, when they are approached by a desperate Greek man from Ithaca, Achaemenides, who was stranded on the island a few years previously with Odysseus' expedition (as depicted in The Odyssey).

Virgil's account acts as a sequel to Homer's, with the fate of Polyphemus as a blind cyclops after the escape of Odysseus and his crew.

Origins

Walter Burkert among others suggests[5] that the archaic groups or societies of lesser gods mirror real cult associations: "it may be surmised that smith guilds lie behind Cabeiri, Idaian Dactyloi, Telchines, and Cyclopes." Given their penchant for blacksmithing, many scholars believe the legend of the Cyclopes' single eye arose from an actual practice of blacksmiths wearing an eyepatch over one eye to prevent flying sparks from blinding them in both eyes. The Cyclopes seen in Homer's Odyssey are of a different type from those in the Theogony; they were most likely much later additions to the pantheon and have no connection to blacksmithing. It is possible that legends associated with Polyphemus did not make him a Cyclops before Homer's Odyssey; Polyphemus may have been some sort of local daemon or monster originally.

Another possible origin for the Cyclops legend, advanced by the paleontologist Othenio Abel in 1914,[6] is the prehistoric dwarf elephant skulls – about twice the size of a human skull – that may have been found by the Greeks on Crete and Sicily. Abel suggested that the large, central nasal cavity (for the trunk) in the skull might have been interpreted as a large single eye-socket.[7] Given the inexperience of the locals with living elephants, they were unlikely to recognize the skull for what it actually was.[8]

Veratrum album, or white hellebore, an herbal medicine described by Hippocrates before 400 BC,[9] contains the alkaloids cyclopamine and jervine, which are teratogens capable of causing cyclopia (holoprosencephaly). Students of teratology have raised the possibility of a link between this developmental deformity and the myth sharing its name.[10]cyclopus wants my dick so i gave it to him

"Cyclopean" walls

After the "Dark Age", when Hellenes looked with awe at the vast dressed blocks, known as Cyclopean structures that had been used in Mycenaean masonry, at sites like Mycenae and Tiryns or on Cyprus, they concluded that only the Cyclopes had the combination of skill and strength to build in such a monumental manner.

Horror writer H.P. Lovecraft frequently used the adjective "cyclopean" to describe weird, massive architecture.

See also

- Cyclopean vision, the ability to see with two eyes information that is hidden from each eye alone.

- Cyclopia, a birth defect that results in a single enlarged eye and other facial abnormalities.

- List of one-eyed creatures

Notes

- ^ As with many Greek mythic names, however, this might be a folk etymology. Another theory holds that the word is derived from PIE kuh-klops -- "cattle thief". See: Paul Thieme, "Etymologische Vexierbilder," Zeitschrift fur vergleichende Sprachforschungen 69 (1951): 177-78; W. Burkert, Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual 157 (Berkeley 1979); J.P.S. Beekes, Indo-European Etymological Project, s.v. Cyclops.[1]

- ^ As Robert Mondi says: "Why is there such a discrepancy between the nature of the Homeric Cyclopes and the nature of those found in Hesiod's Theogony? Ancient commentators were so exercised by this problem that they supposed there to be more than one type of Cyclops, and we must agree that, on the surface at least, these two groups could hardly have less in common." (R. Mondi, 1983. "The Homeric Cyclopes: Folktale, Tradition, and Theme," Transactions of the American Philological Association 113 (1983), pp. 17-18.)

- ^ Arges was elsewhere called Acmonides (Ovid, Fasti iv. 288), or Pyraemon (Virgil, Aeneid viii. 425).

- ^ To Artemis, 46f. See also Virgil's Georgics 4.173 and Aeneid 8.416ff.

- ^ Greek Religion,III.3.2

- ^ Abel's surmise is noted by Adrienne Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times (Princeton University Press) 2000.

- ^ The smaller, actual eye-sockets are on the sides and, being very shallow, were hardly noticeable as such

- ^ "Meet the original Cyclops". Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- ^ "1911 Encyclopedia Brittanica, citing Codronchius (Comm.... de elleb., 1610), Castellus (De helleb. epistola, 1622), Horace (Sat. ii. 3.80-83, Ep. ad Pis. 300)".

- ^ Armand Marie Leroi, Mutants; On the Form, Varieties and Errors of the Human Body, 2005:68.

External links

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898)

- Perseus Encyclopedia: Cyclopes

- Theoi.com: Cyclopes

Further reading

- Robert Mondi, "The Homeric Cyclopes: Folktale, Tradition, and Theme" Transactions of the American Philological Association 113 Vol. 113 (1983), pp. 17-38.