Eastern Europe

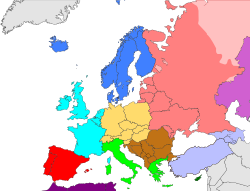

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of the European continent. There is no consensus on the precise area it covers, partly because the term has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, cultural, and socioeconomic connotations. There are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region".[1] A related United Nations paper adds that "every assessment of spatial identities is essentially a social and cultural construct".[2]

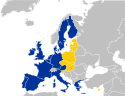

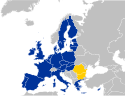

One definition describes Eastern Europe as a cultural entity: the region lying in Europe with the main characteristics consisting of Greek, Byzantine, Eastern Orthodox, Russian, and some Ottoman culture influences.[3][4] Another definition was created during the Cold War and used more or less synonymously with the term Eastern Bloc. A similar definition names the formerly communist European states outside the Soviet Union as Eastern Europe.[4] Some historians and social scientists view such definitions as outdated or relegated,[1][5][6][7][8] but they are still sometimes used for statistical purposes.[3][9][10]

Definitions

Several other definitions of Eastern Europe exist today, but they often lack precision, are too general or outdated. These definitions vary both across cultures and among experts, even political scientists,[11] as the term has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, cultural, and socioeconomic connotations.

There are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region".[1] A related United Nations paper adds that "every assessment of spatial identities is essentially a social and cultural construct".[2]

Geographical

While the eastern geographical boundaries of Europe are well defined, the boundary between Eastern and Western Europe is not geographical but historical, religious and cultural.

The Ural Mountains, Ural River, and the Caucasus Mountains are the geographical land border of the eastern edge of Europe.

In the west, however, the historical and cultural boundaries of "Eastern Europe" are subject to some overlap and, most importantly, have undergone historical fluctuations, which make a precise definition of the western geographic boundaries of Eastern Europe and the geographical midpoint of Europe somewhat difficult.

Religious

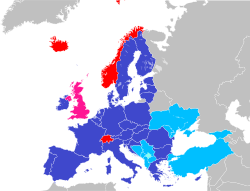

The East–West Schism (which began in the 11th century and lasts until the present) divided Christianity in Europe, and consequently, the world, into Western Christianity and Eastern Christianity.

Western Europe according to this point of view is formed by countries with dominant Roman Catholic and Protestant churches (including Central European countries like Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia).

Eastern Europe is formed by countries with dominant Eastern Orthodox churches, like Belarus, Bulgaria, Greece, Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine for instance.

The schism is the break of communion and theology between what are now the Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (Roman Catholic from the 11th century, as well as from the 16th century also Protestant) churches. This division dominated Europe for centuries, in opposition to the rather short-lived Cold War division of 4 decades.

-

Religious division in 1054[14]

Since the Great Schism of 1054, Europe has been divided between Roman Catholic and Protestant churches in the West, and the Eastern Orthodox Christian (many times incorrectly labeled "Greek Orthodox") churches in the east. Due to this religious cleavage, Eastern Orthodox countries are often associated with Eastern Europe. A cleavage of this sort is, however, often problematic; for example, Greece is overwhelmingly Orthodox, but is very rarely included in "Eastern Europe", for a variety of reasons, the most prominent being that Greece's history, for the most part, was more so influenced by Mediterranean cultures and contact.[15]

Cold War

Another definition was used during the 40 years of Cold War between 1947 and 1989, and was more or less synonymous with the terms Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact. A similar definition names the formerly communist European states outside the Soviet Union as Eastern Europe.[4]

The fall of the Iron Curtain brought the end of the East-West division in Europe,[16] but this geopolitical concept is sometimes still used for quick reference by the media or sometimes for statistical purposes.[17]

Historians and social scientists generally view such definitions as outdated or relegated.[5][6][1][7][8][9][3][10]

Eurovoc

Eurovoc, a multilingual thesaurus maintained by the Publications Office of the European Union, has entries for "23 EU languages"[18] (Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish and Swedish), plus the languages of candidate countries (Albanian, Macedonian and Serbian). Of these, those in italics are classified as "Central and Eastern Europe" in this source.[19]

Contemporary developments

Baltic states

UNESCO[21], EuroVoc, National Geographic Society, Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography, STW Thesaurus for Economics place the Baltic states in Northern Europe, whereas the CIA World Factbook places the region in Eastern Europe with a strong assimilation to Northern Europe. They are members of the Nordic-Baltic Eight regional cooperation forum whereas Central European countries formed their own alliance called the Visegrád Group.[22] The Northern Future Forum, the Nordic Investment Bank and Nordic Battlegroup are other examples of Northern European cooperation that includes the three Baltic states that make up the Baltic Assembly.

Caucasus

The Caucasus nations of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia are included in definitions or histories of Eastern Europe. They are located in the transition zone of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. They participate in the European Union's Eastern Partnership program, the Euronest Parliamentary Assembly, and are members of the Council of Europe, which specifies that all three have political and cultural connections to Europe. In January 2002, the European Parliament noted that Armenia and Georgia may enter the EU in the future.[23] However, Georgia is currently the only Caucasus nation actively seeking NATO and EU membership.

There are three de facto independent Republics with limited recognition in the Caucasus region. All three states participate in the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations:

Other former Soviet states

Several other former Soviet republics may be considered part of Eastern Europe

- Belarus

- Moldova

- Russia is a transcontinental country where the Western part is in Eastern Europe and the Eastern part is in Northern Asia.

- Ukraine

Central Europe

The term "Central Europe" is often used by historians to designate states formerly belonging to the Holy Roman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In some media, "Central Europe" can thus partially overlap with "Eastern Europe" of the Cold War Era. The following countries are labeled Central European by some commentators, though others still consider them to be Eastern European.[24][25][26]

- Austria [27]

- Czech Republic

- Croatia (can variously be included in Southeastern[28] or Central Europe)[29]

- Hungary

- Poland

- Slovakia

- Slovenia (most often placed in Central Europe but sometimes in Southeastern Europe)[30]

Southeastern Europe

Some countries in Southeast Europe can be considered part of Eastern Europe. Some of them can sometimes, albeit rarely, be characterized as belonging to Southern Europe,[3] and some may also be included in Central Europe.

In some media, "Southeast Europe" can thus partially overlap with "Eastern Europe" of the Cold War Era. The following countries are labeled Southeast European by some commentators, though others still consider them to be Eastern European.[31]

- Albania

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Croatia (can variously be included in Southeastern[28] or Central Europe)[29]

- Greece (a rather unusual case; may be included, variously, in Southeastern,[32] Western,[33] or Southern Europe)[34][35]

- Macedonia

- Montenegro

- Romania (can variously be included in Southeastern[36] or Central Europe)[37]

- Serbia (mostly placed in Southeastern but sometimes in Central Europe)[38]

- Slovenia (most often placed in Central Europe but sometimes in Southeastern Europe)[30]

- Turkey (only the region East Thrace, west of the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara, and the Bosphorus; constitutes less than 3% of the country's total land mass)

History

Classical antiquity and medieval origins

Ancient kingdoms of the region included Orontid Armenia Albania, Colchis and Iberia (not to be confused with the people of Iberian Peninsula in Western Europe). These kingdoms were either from the start, or later on incorporated into various Iranian empires, including the Achaemenid Persian, Parthian, and Sassanid Persian Empires.[39] Parts of the Balkans and more northern areas were ruled by the Achaemenid Persians as well, including Thrace, Paeonia, Macedon, and most of the Black Sea coastal regions of Romania, Ukraine, and Russia.[40][41] Owing to the rivalry between Parthian Iran and Rome, and later Byzantium and the Sassanid Persians, the former would invade the region several times, although it was never able to hold the region, unlike the Sassanids who ruled over most of the Caucasus during their entire rule.[42]

The earliest known distinctions between east and west in Europe originate in the history of the Roman Republic. As the Roman domain expanded, a cultural and linguistic division appeared between the mainly Greek-speaking eastern provinces which had formed the highly urbanized Hellenistic civilization. In contrast, the western territories largely adopted the Latin language. This cultural and linguistic division was eventually reinforced by the later political east-west division of the Roman Empire. The division between these two spheres was enhanced during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages by a number of events. The Western Roman Empire collapsed starting the Early Middle Ages. By contrast, the Eastern Roman Empire, mostly known as the Byzantine Empire, managed to survive and even to thrive for another 1,000 years. The rise of the Frankish Empire in the west, and in particular the Great Schism that formally divided Eastern and Western Christianity, enhanced the cultural and religious distinctiveness between Eastern and Western Europe. Much of Eastern Europe was invaded and occupied by the Mongols.

The conquest of the Byzantine Empire, center of the Eastern Orthodox Church, by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century, and the gradual fragmentation of the Holy Roman Empire (which had replaced the Frankish empire) led to a change of the importance of Roman Catholic/Protestant vs. Eastern Orthodox concept in Europe. Armour points out that the Cyrillic alphabet use is not a strict determinant for Eastern Europe, where from Croatia to Poland and everywhere in between, the Latin alphabet is used.[43] Greece's status as the cradle of Western civilization and an integral part of the Western world in the political, cultural and economic spheres has led to it being nearly always classified as belonging not to Eastern, but to Southern or Western Europe.[44] During the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries Eastern Europe enjoyed a relatively high standard of living. This period is also called the east-central European golden age of around 1600.[45]

Interwar years

A major result of the First World War was the breakup of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires, as well as partial losses to the German Empire. A surge of ethnic nationalism created a series of new states in Eastern Europe, validated by the Versailles Treaty of 1919. Poland was reconstituted after the partitions of the 1790s had divided it between Germany, Austria, and Russia. New countries included Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine (which was soon absorbed by the Soviet Union), Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. Austria and Hungary had much-reduced boundaries. Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania likewise were independent. Many of the countries were still largely rural, with little industry and only a few urban centers. Nationalism was the dominant force but most of the countries had ethnic or religious minorities who felt threatened by majority elements. Nearly all became democratic in the 1920s, but all of them (except Czechoslovakia and Finland) gave up democracy during the depression years of the 1930s, in favor of autocratic or strong-man or single-party states. The new states were unable to form stable military alliances, and one by one were too weak to stand up against Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union, which took them over between 1938 and 1945.

World War II and the onset of the Cold War

Russia ended its participation in the First World War in March 1918 and lost territory, as the Baltic countries and Poland became independent. The region was the main battlefield in the Second World War (1939–45), with German and Soviet armies sweeping back and forth, with millions of Jews killed by the Nazis, and millions of others killed by disease, starvation, and military action, or executed after being deemed as politically dangerous.[46] During the final stages of World War II the future of Eastern Europe was decided by the overwhelming power of the Soviet Red Army, as it swept the Germans aside. It did not reach Yugoslavia and Albania however. Finland was free but forced to be neutral in the upcoming Cold War. The region fell to Soviet control and Communist governments were imposed. Yugoslavia and Albania had their own Communist regimes. The Eastern Bloc with the onset of the Cold War in 1947 was mostly behind the Western European countries in economic rebuilding and progress. Winston Churchill, in his famous "Sinews of Peace" address of March 5, 1946 at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, stressed the geopolitical impact of the "iron curtain":

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest, and Sofia.

Eastern Bloc during the Cold War to 1989

Eastern Europe after 1945 usually meant all the European countries liberated and then occupied by the Soviet army. It included the German Democratic Republic (also known as East Germany), formed by the Soviet occupation zone of Germany. All the countries in Eastern Europe adopted communist modes of control. These countries were officially independent from the Soviet Union, but the practical extent of this independence – except in Yugoslavia, Albania, and to some extent Romania – was quite limited.

The Soviet secret police, the NKVD, working in collaboration with local communists, created secret police forces using leadership trained in Moscow. As soon as the Red Army had expelled the Germans, this new secret police arrived to arrest political enemies according to prepared lists. The national Communists then took power in a normally gradualist manner, backed by the Soviets in many, but not all, cases. They took control of the Interior Ministries, which controlled the local police. They confiscated and redistributed farmland. Next the Soviets and their agents took control of the mass media, especially radio, as well as the education system. Third the communists seized control of or replaced the organizations of civil society, such as church groups, sports, youth groups, trade unions, farmers organizations, and civic organizations. Finally they engaged in large scale ethnic cleansing, moving ethnic minorities far away, often with high loss of life. After a year or two, the communists took control of private businesses and monitored the media and churches. For a while, cooperative non-Communist parties were tolerated. The communists had a natural reservoir of popularity in that they had destroyed Hitler and the Nazi invaders. Their goal was to guarantee long-term working-class solidarity.[47][48]

Under pressure from Stalin these nations rejected grants from the American Marshall plan. Instead they participated in the Molotov Plan which later evolved into the Comecon (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance). When NATO was created in 1949, most countries of Eastern Europe became members of the opposing Warsaw Pact, forming a geopolitical concept that became known as the Eastern Bloc.

- First and foremost was the Soviet Union (which included the modern-day territories of Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova). Other countries dominated by the Soviet Union were the German Democratic Republic, People's Republic of Poland, Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, People's Republic of Hungary, People's Republic of Bulgaria, and Socialist Republic of Romania.

- The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY; formed after World War II and before its later dismemberment) was not a member of the Warsaw Pact. It was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement, an organization created in an attempt to avoid being assigned to either the NATO or Warsaw Pact blocs. The movement was demonstratively independent from both the Soviet Union and the Western bloc for most of the Cold War period, allowing Yugoslavia and its other members to act as a business and political mediator between the blocs.

- The Socialist People's Republic of Albania broke with the Soviet Union in the early 1960s as a result of the Sino-Soviet split, aligning itself instead with China. Albania formally left the Warsaw pact in September 1968 after the suppression of the Prague spring. When China established diplomatic relations with the United States in 1978, Albania also broke away from China. Albania and especially Yugoslavia were not unanimously appended to the Eastern Bloc, as they were neutral for a large part of the Cold War period.

Since 1989

With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, the political landscape of the Eastern Bloc, and indeed the world, changed. In the German reunification, the Federal Republic of Germany peacefully absorbed the German Democratic Republic in 1990. In 1991, COMECON, the Warsaw Pact, and the Soviet Union were dissolved. Many European nations which had been part of the Soviet Union regained their independence (Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine, as well as the Baltic States of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia). Czechoslovakia peacefully separated into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993. Many countries of this region joined the European Union, namely Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

See also

- Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations

- Eastern European Group

- Eastern Partnership

- Enlargement of the European Union

- Eurasian Economic Union

- Euronest Parliamentary Assembly

- Eurovoc

- Future enlargement of the European Union

- Geography of the Soviet Union

- List of political parties in Eastern Europe

- N-ost

- Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation

- Post-Soviet States

- East Slavs

- South Slavs

- Orthodox Slavs

- Russian explorers

- Albanians

- Eastern Romance people

- European Union

- Intermarium

- European geography

- Eurovoc#Eastern Europe

- Central Europe

- Northern Europe

- Southeast Europe

- Western Europe

- Central and Eastern Europe

- East-Central Europe

- European Russia

- Geographical midpoint of Europe

- Regions of Europe

References

- ^ a b c d e "The Balkans", Global Perspectives: A Remote Sensing and World Issues Site. Wheeling Jesuit University/Center for Educational Technologies, 1999–2002.

- ^ a b "Jordan Europa Regional". 4 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "United Nations Statistics Division- Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49)-Geographic Regions".

- ^ a b c Ramet, Sabrina P. (1998). Eastern Europe: politics, culture, and society since 1939. Indiana University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0253212561. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ a b c "Regions, Regionalism, Eastern Europe by Steven Cassedy". New Dictionary of the History of Ideas, Charles Scribner's Sons. 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c ""Eastern Europe" Wrongly labelled". economist.com.

- ^ a b c "A New Journal for Central Europe". www.ce-review.org.

- ^ a b c Frank H. Aarebrot (14 May 2014). The handbook of political change in Eastern Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-1-78195-429-4.

- ^ a b [1] Archived April 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Eurovoc.europa.eu. Retrieved on 2015-03-04.

- ^ a b c "Population Division, DESA, United Nations: World Population Ageing 1950-2050" (PDF).

- ^ Drake, Miriam A. (2005) Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, CRC Press

- ^ "Atlas of the Historical Geography of the Holy Land". Rbedrosian.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "home.comcast.net". Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dragan Brujić (2005). "Vodič kroz svet Vizantije (Guide to the Byzantine World)". Beograd. p. 51.[dead link]

- ^ Peter John, Local Governance in Western Europe, University of Manchester, 2001, ISBN 9780761956372

- ^ V. Martynov, The End of East-West Division But Not the End of History, UN Chronicle, 2000 (available online[dead link])

- ^ "Migrant workers: What we know". BBC News. 2007-08-21.

- ^ "EuroVoc". European Union. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ "EuroVoc – 7206 Europe". European Union. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ European Parliament, European Parliament Resolution 2014/2717(RSP), 17 July 2014: “...pursuant to Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine – like any other European state – have a European perspective and may apply to become members of the Union...”

- ^ Division, United Nations Statistics. "UNSD — Methodology". unstats.un.org.

- ^ http://www.visegradgroup.eu/about About the Visegrad Group

- ^ How Armenia Could Approach the European Union (PDF)

- ^ Wallace, W. The Transformation of Western Europe London, Pinter, 1990

- ^ Huntington, Samuel The Clash of Civilizations Simon & Schuster, 1996

- ^ Johnson, Lonnie Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbours, Friends Oxford University Press, USA, 2001

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/atlas/programmes/2014-2020/europe/2014tc16rftn003

- ^ a b "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- ^ a b Lonnie Johnson, Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbors, Friends, Oxford University Pres

- ^ a b Armstrong, Werwick. Anderson, James (2007). "Borders in Central Europe: From Conflict to Cooperation". Geopolitics of European Union Enlargement: The Fortress Empire. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-134-30132-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bideleux and Jeffries (1998) A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change

- ^ Greek Ministry of Tourism Travel Guide, General Information Archived 2010-03-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ inter alia, Peter John, Local Governance in Western Europe, 2001

- ^ "Greece Location - Geography". indexmundi.com. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- ^ "UNdata | country profile | Greece". data.un.org. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- ^ Energy Statistics for the U.S. Government Archived February 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "7 Invitees - Romania".

- ^ Comparative Hungarian Cultural Studies. Purdue University Press. 2011. ISBN 9781557535931.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Rapp, Stephen H. (2003), Studies In Medieval Georgian Historiography: Early Texts And Eurasian Contexts, pp. 292-294. Peeters Bvba ISBN 90-429-1318-5.

- ^ The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth,ISBN 0-19-860641-9,"page 1515,"The Thracians were subdued by the Persians by 516"

- ^ "A Companion to Ancient Macedonia". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Armour, Ian D. 2013. A History of Eastern Europe 1740–1918: Empires, Nations and Modernisation. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 23. ISBN 978-1849664882

- ^ See, inter alia, Norman Davies, Europe: a History, 2010, Eve Johansson, Official Publications of Western Europe, Volume 1, 1984, Thomas Greer and Gavin Lewis, A Brief History of the Western World, 2004

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (2011) excerpt and text search

- ^ Anne Applebaum (2012). Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 31–33. ISBN 9780385536431.

- ^ Also Anne Applebaum, Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944–1956 introduction, pp xxix–xxxi online at Amazon.com

Further reading

- Applebaum, Anne. Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944–1956 (2012)

- Berend, Iván T. Decades of Crisis: Central and Eastern Europe before World War II (2001)

- Frankel, Benjamin. The Cold War 1945-1991. Vol. 2, Leaders and other important figures in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, and the Third World (1992), 379pp of biographies.

- Frucht, Richard, ed. Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism (2000)

- Gal, Susan and Gail Kligman, The Politics of Gender After Socialism, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Ghodsee, Kristen R.. Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, Ethnicity and the Transformation of Islam in Postsocialist Bulgaria. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Ghodsee, Kristen R.. Lost in Transition: Ethnographies of Everyday Life After Communism, Duke University Press, 2011.

- Held, Joseph, ed. The Columbia History of Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century (1993)

- Jelavich, Barbara. History of the Balkans, Vol. 1: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (1983); History of the Balkans, Vol. 2: Twentieth Century (1983)

- Lipton, David (2002). "Eastern Europe". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563 - Myant, Martin; Drahokoupil, Jan (2010). Transition Economies: Political Economy in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-59619-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Ramet, Sabrina P. Eastern Europe: Politics, Culture, and Society Since 1939 (1999)

- Roskin, Michael G. The Rebirth of East Europe (4th ed. 2001); 204pp

- Seton-Watson, Hugh. Eastern Europe Between The Wars 1918-1941 (1945) online

- Simons, Thomas W. Eastern Europe in the Postwar World (1991)

- Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (2011)

- Swain, Geoffrey and Nigel Swain, Eastern Europe Since 1945 (3rd ed. 2003)

- Verdery, Katherine. What Was Socialism and What Comes Next? Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Walters, E. Garrison. The Other Europe: Eastern Europe to 1945 (1988) 430pp; country-by-country coverage

- Wolchik, Sharon L. and Jane L. Curry, eds. Central and East European Politics: From Communism to Democracy (2nd ed. 2010), 432pp

![Division between the Eastern and Western Churches[12][13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a8/Expansion_of_christianity.jpg/120px-Expansion_of_christianity.jpg)

![Religious division in 1054[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/Great_Schism_1054_with_former_borders.png/112px-Great_Schism_1054_with_former_borders.png)