Eastern Han Chinese

| Eastern Han Chinese | |

|---|---|

| Later Han Chinese | |

| Native to | China |

| Era | Eastern Han dynasty |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Clerical script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

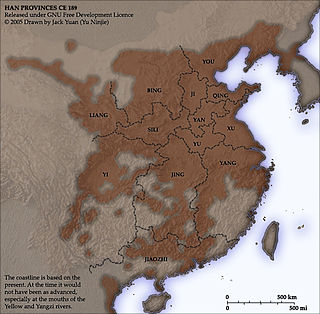

Provinces in the Eastern Han period | |

Eastern Han Chinese or Later Han Chinese is the stage of the Chinese language revealed by poetry and glosses from the Eastern Han period (first two centuries AD). It is considered an intermediate stage between Old Chinese and the Middle Chinese of the 7th-century Qieyun dictionary.

Sources

The rhyming practice of Han poets has been studied since the Qing period as an intermediate stage between the Shijing of the Western Zhou period and Tang poetry. The definitive reference was compiled by Luo Changpei and Zhou Zumo in 1958.[a] This monumental work identifies the rhyme classes of the period, but leaves the phonetic value of each class open.[1]

In the Eastern Han period, Confucian scholars were bitterly divided between different versions of the classics: the officially recognized New Texts, and the Old Texts, recently found versions written in a pre-Qin script. To support their challenge to the orthodox position on the classics, Old Text scholars produced many philological studies. These include Xu Shen's Shuowen Jiezi, a study of the history and structure of Chinese characters, the Shiming, a dictionary of classical terms, and several others. Many of these works contain remarks of various types on the pronunciation of various words.[2]

Buddhism also expanded greatly in China during the Eastern Han period. Many Buddhist texts translated into Chinese at the time include transcriptions in Chinese characters of Sanskrit and Prakrit names and terms.[3] These were first systematically mined for evidence of the evolution of Chinese phonology by Edwin Pulleyblank.[4]

The Shiming glosses were collected and studied by Nicholas Bodman.[5] Weldon South Coblin collected all the remaining glosses and transcriptions, and used them in an attempt to reconstruct an intermediate stage between Old Chinese and Middle Chinese, both represented by the reconstructions of Li Fang-Kuei.[6] Axel Schuessler included reconstructed pronunciations (under the name Later Han Chinese) in his dictionary of Old Chinese.[7][8]

Dialects

Several texts contain evidence of dialectal variation in the Eastern Han period. The Fangyan, from the start of the period, discusses variations in regional vocabulary. By analysing the text, Paul Serruys identified six dialect areas: a central area centred on the Central Plain east of Hangu Pass, surrounded by northern, eastern, southern and western areas, and a southeastern area to the southeast of the lower Yangtze.[9][10]

Eastern Han texts contain little information on the southeastern dialects, but the Eastern Jin writer Guo Pu describes them as quite distinct from other varieties.[11] Jerry Norman called these Han-era dialects Old Southern Chinese, and suggested that they were the source of common features found in the oldest layers of modern Yue, Hakka and Min varieties.[12]

The Eastern Han glosses provide limited coverage of the remaining areas, but often show marked phonological differences. Many of them exhibit mergers that are not found in the 7th-century Qieyun or in many modern varieties. The exception is the Buddhist transcriptions, suggesting that the later varieties descend from Han-period varieties spoken in the Luoyang area.[13]

Phonology

The consonant clusters postulated for Old Chinese had generally disappeared by the Eastern Han period.[14][15]

One of the major changes between Old Chinese and Middle Chinese is palatalization of initial dental stops and (in some environments) velar stops, merging to form a new series of palatal initials. Either or both of palatalizations are found in several Eastern Han varieties.[16] However, Proto-Min, which branched off during the Han period, has palatalized velars but not dentals.[17] However, the retroflex stops and sibilants of Middle Chinese are not distinguished as separate series in the Eastern Han data.[18]

Some Eastern Han dialects show evidence of the voiceless sonorant initials postulated for Old Chinese, but they had disappeared by the Eastern Han period in most areas.[19] The Old Chinese voiceless lateral and nasal initials yielded a *tʰ initial in eastern dialects and *x in western ones.[20][21]

Most modern reconstructions of Old Chinese distinguish labiovelar and labiolaryngeal initials from the velar and laryngeal series. However, the two series are not separated in Eastern Han glosses. Thus it seems Eastern Han Chinese had a *-w- medial, like Middle Chinese. Moreover, this medial also occurs after other initials.[22][23] In addition, Eastern Han Chinese had medials *-r- and *-j-.[24]

In some Eastern Han varieties, words with the Middle Chinese coda -n appear to have vocalic codas.[25] Baxter and Sagart argue that these words had a coda *r in Old Chinese, which became *j in Shandong and adjacent areas, and *n elsewhere.[26]

André-Georges Haudricourt suggested that the Middle Chinese departing tone derived from an Old Chinese final *-s, later weakening to *-h.[27] Several Buddhist transcriptions indicate that *-s was still present in the Eastern Han period.[28]

Notes

References

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 43, 30–31.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 43, 131–132.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 120–121.

- ^ Schuessler (2009), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Serruys (1959), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 19–22.

- ^ Coblin (1983), p. 25.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 210–214.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 39, 132–135.

- ^ Schuessler (2009), p. 29.

- ^ Coblin (1977–78), pp. 245–246.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 54–59, 75–76, 132.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 33, 76, 79.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 46–47, 53–54.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 133–135.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 112–114, 320.

- ^ Coblin (1977–78), pp. 228–232.

- ^ Coblin (1983), p. 77.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 77–79.

- ^ Coblin (1983), pp. 89–92.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 254–268, 319.

- ^ Coblin (1983), p. 92.

- ^ Schuessler (2009), p. 30.

Works cited

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Coblin, W. South (1977–78), "The initials of the Eastern Han period as reflected in phonological cases", Monumenta Serica, 33: 207–247, JSTOR 40726240.

- —— (1983), A Handbook of Eastern Han Sound Glosses, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, ISBN 962-201-258-2.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007), ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- —— (2009), Minimal Old Chinese and Later Han Chinese: A Companion to Grammata Serica Recensa, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3264-3.

- Serruys, Paul L-M. (1959), The Chinese Dialects of Han Time According to Fang Yen, University of California Press, OCLC 469563424.