Guerrilla warfare: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 509: | Line 509: | ||

[[be:Партызанская вайна]] |

[[be:Партызанская вайна]] |

||

[[bg:Партизани]] |

[[bg:Партизани]] |

||

[[ca: |

[[ca:bndfyrgy |

||

[[cs:Partyzánská válka]] |

[[cs:Partyzánská válka]] |

||

[[cy:Rhyfela herwfilwrol]] |

[[cy:Rhyfela herwfilwrol]] |

||

Revision as of 15:48, 16 October 2008

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Guerrilla warfare is the unconventional warfare and combat with which a small group of combatants use mobile tactics (ambushes, raids, etc.) to combat a larger and less mobile formal army. The guerrilla army uses ambush (advantage and surprise) and mobility (draw enemy forces to terrain unsuited to them) in attacking vulnerable targets in enemy territory.

This term means "little war" in Spanish and was created during the Peninsular War. The concept acknowledges a conflict between armed civilians against a powerful nation state army. This tactic was used by the Viet Cong and North Vietnam Army in the Vietnam War. Most factions of the Iraqi Insurgency and groups such as FARC are said to be engaged in some form of Guerrilla warfare.

Etymology

Guerrilla means small war, the diminutive of the Spanish word Guerra (war). The Spanish word derives from the Old High German word Werra and from the middle Dutch word warre; adopted by the Visigoths in A.D. 5th century Hispania. The use of the diminutive evokes the differences in number, scale, and scope between the guerrilla army and the formal, professional army of the state. The word was coined in Spain to describe their warfare in resisting Napoleon Bonaparte's French régime during the Peninsula War, its meaning was broadened to mean any similar-scale armed resistance. Guerrillero is the Spanish word for guerrilla fighter, while in Spanish-speaking countries the noun guerrilla usually denotes guerrilla army (e.g. la guerrilla de las FARC translates as "the FARC guerrilla group"). Moreover, per the OED, 'the guerrilla' was an English usage (as early as 1809), describing the fighters, not only their tactics (e.g."the town was taken by the guerrillas"), however, in most languages guerrilla still denotes the specific style of warfare. [citation needed]

Strategy, tactics and organization

The guerrilla band is an armed nucleus, the fighting vanguard of the people. It draws its great force from the mass of the people themselves. The guerrilla band is not to be considered inferior to the army against which it fights simply because it is inferior in fire power. Guerrilla warfare is used by the side which is supported by a majority but which possesses a much smaller number of arms for use in defense against oppression.

Guerrilla warfare as a continuum

An insurgency, or what Mao Zedong referred to as a war of revolutionary nature, guerrilla warfare can be conceived of as part of a continuum.[2] On the low end are small-scale raids, ambushes and attacks. In ancient times these actions were often associated with smaller tribal polities fighting a larger empire, as in the struggle of Rome against the Spanish tribes for over a century. In the modern era they continue with the operations of insurgent, revolutionary and "terrorist" groups. The upper end is composed of a fully integrated political-military strategy, comprising both large and small units, engaging in constantly shifting mobile warfare, both on the low-end "guerrilla" scale, and that of large, mobile formations with modern arms.

The latter phase came to fullest expression in the operations of Mao Zedong in China and Vo Nguyen Giap in Vietnam. In between are a large variety of situations - from the wars waged against Israel by Palestinian irregulars in the contemporary era, to Spanish and Portuguese irregulars operating with the conventional units of British General Wellington, during the Peninsular War against Napoleon.[3]

Modern insurgencies and other types of warfare may include guerrilla warfare as part of an integrated process, complete with sophisticated doctrine, organization, specialist skills and propaganda capabilities. Guerrillas can operate as small, scattered bands of raiders, but they can also work side by side with regular forces, or combine for far ranging mobile operations in squad, platoon or battalion sizes, or even form conventional units. Based on their level of sophistication and organization, they can shift between all these modes as the situation demands. Successful guerrilla warfare is flexible, not static.

Strategic models of guerrilla warfare

The 'classic' three-phase Maoist model

In China, the Maoist Theory of People's War divides warfare into three phases. In Phase One, the guerrillas earn population's support by distributing propaganda and attacking the organs of government. In Phase Two, escalating attacks are launched against the government's military forces and vital institutions. In Phase Three, conventional warfare and fighting are used to seize cities, overthrow the government, and assume control of the country. Mao's doctrine anticipated that circumstances may require shifting between phases in either directions and that the phases may not be uniform and evenly paced throughout the countryside. Mao Zedong's seminal work, On Guerrilla Warfare,[4] has been widely distributed and applied most successfully in Vietnam, by military leader and theorist Vo Nguyen Giap, whose "Peoples War, Peoples Army"[5] closely follows the Maoist three-phase approach, but emphasizing flexibility in shifting between guerrilla warfare and a spontaneous "General Uprising" of the population in conjunction with guerrilla forces.

The more fragmented contemporary pattern

The classical Maoist model requires a strong, unified guerrilla group and a clear objective. However, some contemporary guerrilla warfare may not follow this template at all, and might encompass vicious ethnic strife, religious fervor, and numerous small, 'freelance' groups operating independently with little overarching structure. These patterns do not fit easily into neat phase-driven categories, or formal 3-echelon structures (Main Force regulars, Regional fighters, part-time Guerrillas) as in the People's Wars of Asia.

Some jihadist guerrilla attacks for example, may be driven by a generalized desire to restore a reputed golden age of earlier times, with little attempt to establish a specific alternative political regime in a specific place. Ethnic attacks likewise may remain at the level of bombings, assassinations, or genocidal raids as a matter of avenging some perceived slight or insult, rather than a final shift to conventional warfare as in the Maoist formulation.[6]

Environmental conditions such as increasing urbanization, and the easy access to information and media attention also complicate the contemporary scene. Guerrillas need not conform to the classic rural fighter helped by cross-border sanctuaries in a confined nation or region, (as in Vietnam) but now include vast networks of peoples bound by religion and ethnicity stretched across the globe.[7]

Tactics of guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is distinguished from the small unit tactics used in screening or reconnaissance operations typical of conventional forces. It is also different from the activities of bandits, pirates or robbers. Such criminal groups may use guerrilla-like tactics, but their primary purpose is immediate material gain, and not a political objective.

Guerrilla tactics are based on intelligence, ambush, deception, sabotage, and espionage, undermining an authority through long, low-intensity confrontation. It can be quite successful against an unpopular foreign or local regime, as demonstrated by the Vietnam conflict. A guerrilla army may increase the cost of maintaining an occupation or a colonial presence above what the foreign power may wish to bear. Against a local regime, the guerrilla fighters may make governance impossible with terror strikes and sabotage, and even combination of forces to depose their local enemies in conventional battle. These tactics are useful in demoralizing an enemy, while raising the morale of the guerrillas. In many cases, guerrilla tactics allow a small force to hold off a much larger and better equipped enemy for a long time, as in Russia's Second Chechen War and the Second Seminole War fought in the swamps of Florida (United States of America). Guerrilla tactics and strategy are summarized below and are discussed extensively in standard reference works such as Mao's "On Guerrilla Warfare."[4]

Types of tactical operations

Guerrilla operations typically include a variety of strong surprise attacks on transportation routes, individual groups of police or military, installations and structures, economic enterprises, and targeted civilians. Attacking in small groups, using camouflage and often captured weapons of that enemy, the guerrilla force can constantly keep pressure on its foes and diminish its numbers, while still allowing escape with relatively few casualties. The intention of such attacks is not only military but political, aiming to demoralize target populations or governments, or goading an overreaction that forces the population to take sides for or against the guerrillas. Examples range from the chopping off of limbs in various internal African rebellions, to the suicide bombings in Israel and Sri Lanka, to sophisticated manoeuvres by Viet Cong and NVA forces against military bases and formations.

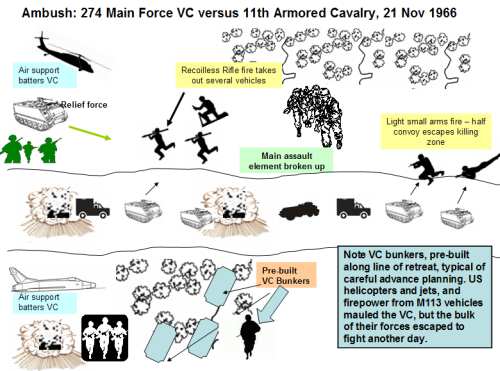

Whatever the particular tactic used, the guerrilla primarily lives to fight another day, and to expand or preserve his forces and political support, not capture or holding specific blocks of territory as a conventional force would. Below is a simplified version of a typical ambush attack by one of the most effective of post-WWII guerrilla forces, the Viet Cong (VC).

Ambushes on key transportation routes are a hallmark of guerrilla operations, causing both economic and political disruption. Careful advance planning is required for operations, indicated here by VC preparation of the withdrawal route. In this case - the Viet Cong assault was broken up by American aircraft and firepower. However, the VC did destroy several vehicles and the bulk of the main VC force escaped. As in most of the Vietnam conflict, American forces would eventually leave the area, but the insurgents would regroup and return afterwards. This time dimension is also integral to guerrilla tactics.[9]

Organization

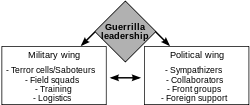

Guerrilla warfare resembles rebellion, yet it is a different concept. Guerrilla organization ranges from small, local rebel groups of a few dozen guerrillas, to thousands of fighters, deploying from cells to regiments. In most cases, the leaders have clear political aims for the warfare they wage. Typically, the organization has political and military wings, to allow the political leaders "plausible denial" for military attacks.[10] The most fully elaborated guerrilla warfare structure is by the Chinese and Vietnamese communists during the revolutionary wars of East and Southeast Asia.[11] A simplified example of this more sophisticated organizational type - used by revolutionary forces during the Vietnam War, is shown below.

Surprise and intelligence

For successful operations, surprise must be achieved by the guerrillas. If the operation has been betrayed or compromised it is usually called off immediately. Intelligence is also extremely important, and detailed knowledge of the target's dispositions, weaponry and morale is gathered before any attack. Intelligence can be harvested in several ways. Collaborators and sympathizers will usually provide a steady flow of useful information. If working clandestinely, the guerrilla operative may disguise his membership in the insurgent operation, and use deception to ferret out needed data. Employment or enrollment as a student may be undertaken near the target zone, community organizations may be infiltrated, and even romantic relationships struck up as part of intelligence gathering.[12] Public sources of information are also invaluable to the guerrilla, from the flight schedules of targeted airlines, to public announcements of visiting foreign dignitaries, to Army Field Manuals. Modern computer access via the World Wide Web makes harvesting and collation of such data relatively easy.[13] The use of on the spot reconnaissance is integral to operational planning. Operatives will "case" or analyze a location or potential target in depth- cataloguing routes of entry and exit, building structures, the location of phones and communication lines, presence of security personnel and a myriad of other factors. Finally intelligence is concerned with political factors- such as the occurrence of an election or the impact of the potential operation on civilian and enemy morale.

Relationships with the civil population

Why does the guerrilla fighter fight? We must come to the inevitable conclusion that the guerrilla fighter is a social reformer, that he takes up arms responding to the angry protest of the people against their oppressors, and that he fights in order to change the social system that keeps all his unarmed brothers in ignominy and misery.

Relationships with civilian populations are influenced by whether the guerrillas operate among a hostile or friendly population. A friendly population is of immense importance to guerrilla fighters, providing shelter, supplies, financing, intelligence and recruits. The "base of the people" is thus the key lifeline of the guerrilla movement. In the early stages of the Vietnam War, American officials "discovered that several thousand supposedly government-controlled 'fortified hamlets' were in fact controlled by Viet Cong guerrillas, who 'often used them for supply and rest havens'."[15] Popular mass support in a confined local area or country however is not always strictly necessary. Guerrillas and revolutionary groups can still operate using the protection of a friendly regime, drawing supplies, weapons, intelligence, local security and diplomatic cover.

An apathetic or hostile population makes life difficult for guerrilleros and strenuous attempts are usually made to gain their support. These may involve not only persuasion, but a calculated policy of intimidation. Guerrilla forces may characterize a variety of operations as a liberation struggle, but this may or may not result in sufficient support from affected civilians. Other factors, including ethnic and religious hatreds, can make a simple national liberation claim untenable. Whatever the exact mix of persuasion or coercion used by guerrillas, relationships with civil populations are one of the most important factors in their success or failure.[16]

Use of terror

In some cases, the use of terror can be an aspect of guerrilla warfare. Terror is used to focus international attention on the guerrilla cause, kill opposition leaders, extort money from targets, intimidate the general population, create economic losses, and keep followers and potential defectors in line. As well, the use of terrorism can provoke the greater power to launch a disproportionate response, thus alienating a civilian population which might be sympathetic to the terrorist's cause. Such tactics may backfire and cause the civil population to withdraw its support, or to back countervailing forces against the guerrillas.[17]

Such situations occurred in Israel, where suicide bombings encouraged most Israeli opinion to take a harsh stand against Palestinian attackers, including general approval of "targeted killings" to kill enemy cells and leaders.[18] In the Philippines and Malaysia, communist terror strikes helped turn civilian opinion against the insurgents. In Peru and some other countries, civilian opinion at times backed the harsh countermeasures used by governments against revolutionary or insurgent movements.

Withdrawal

Guerrillas must plan carefully for withdrawal once an operation has been completed, or if it is going badly. The withdrawal phase is sometimes regarded as the most important part of a planned action, and to get entangled in a lengthy struggle with superior forces is usually fatal to insurgent, terrorist or revolutionary operatives. Withdrawal is usually accomplished using a variety of different routes and methods and may include quickly scouring the area for loose weapons, evidence cleanup, and disguise as peaceful civilians.[4]

Logistics

Guerrillas typically operate with a smaller logistical footprint compared to conventional formations; nevertheless, their logistical activities can be elaborately organized. A primary consideration is to avoid dependence on fixed bases and depots which are comparatively easy for conventional units to locate and destroy. Mobility and speed are the keys and wherever possible, the guerrilla must live off the land, or draw support from the civil population in which he is embedded. In this sense, "the people" become the guerrilla's supply base.[4] Financing of both terrorist and guerrilla activities ranges from direct individual contributions (voluntary or non-voluntary), and actual operation of business enterprises by insurgent operatives, to bank robberies, kidnappings and complex financial networks based on kin, ethnic and religious affiliation (such as that used by modern Jihadist/Jihad organizations).

Permanent and semi-permanent bases form part of the guerrilla logistical structure, usually located in remote areas or in cross-border sanctuaries sheltered by friendly regimes.[19] These can be quite elaborate, as in the tough VC/NVA fortified base camps and tunnel complexes encountered by US forces during the Vietnam War. Their importance can be seen by the hard fighting sometimes engaged in by communist forces to protect these sites. However, when it became clear that defence was untenable, communist units typically withdrew without sentiment.

Terrain

Guerrilla warfare is often associated with a rural setting, and this is indeed the case with the definitive operations of Mao and Giap, the mujahadeen of Afghanistan, the Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres (EGP) of Guatemala, the Contras of Nicaragua, and the FMLN of El Salvador. Guerrillas however have successfully operated in urban settings as demonstrated in places like Argentina and Northern Ireland. In those cases, guerrillas rely on a friendly population to provide supplies and intelligence. Rural guerrillas prefer to operate in regions providing plenty of cover and concealment, especially heavily forested and mountainous areas. Urban guerrillas, rather than melting into the mountains and jungles, blend into the population and are also dependent on a support base among the people. Rooting guerrilleros out of both types of areas can be difficult.

Foreign support and sanctuaries

Foreign support in the form of soldiers, weapons, sanctuary, or statements of sympathy for the guerrillas is not strictly necessary, but it can greatly increase the chances of an insurgent victory.[12] Foreign diplomatic support may bring the guerrilla cause to international attention, putting pressure on local opponents to make concessions, or garnering sympathetic support and material assistance. Foreign sanctuaries can add heavily to guerrilla chances, furnishing weapons, supplies, materials and training bases. Such shelter can benefit from international law, particularly if the sponsoring government is successful in concealing its support and in claiming "plausible denial" for attacks by operatives based in its territory.

The VC and NVA made extensive use of such international sanctuaries during their conflict, and the complex of trails, way-stations and bases snaking through Laos and Cambodia, the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail, was the logistical lifeline that sustained their forces in the South. Also, the United States funded a revolution in Colombia in order to take the territory they needed to build the Panama Canal. Another case in point is the Mukti Bahini guerrilleros who fought alongside the Indian Army in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 against Pakistan that resulted in the creation of the state of Bangladesh. In the post-Vietnam era, the Al Qaeda organization also made effective use of remote territories, such as Afghanistan under the Taliban regime, to plan and execute its operations.

Guerrilla initiative and combat intensity

Able to choose the time and place to strike, guerrilla fighters will usually possess the tactical initiative and the element of surprise. Planning for an operation may take weeks, months or even years, with a constant series of cancellations and restarts as the situation changes.[20] Careful rehearsals and "dry runs" are usually conducted to work out problems and details. Many guerrilla strikes are not undertaken unless clear numerical superiority can be achieved in the target area, a pattern typical of VC/NVA and other "Peoples War" operations. Individual suicide bomb attacks offer another pattern, typically involving only the individual bomber and his support team, but these too are spread or metered out based on prevailing capabilities and political winds.

Whatever approach is used, the guerrilla holds the initiative and can prolong his survival though varying the intensity of combat. This means that attacks are spread out over quite a range of time, from weeks to years. During the interim periods, the guerrilla can rebuild, resupply and plan. In the Vietnam War, most communist units (including mobile NVA regulars using guerrilla tactics) spent only a limited number of days a year fighting. While they might be forced into an unwanted battle by an enemy sweep, most of the time was spent in training, intelligence gathering, political and civic infiltration, propaganda indoctrination, construction of fortifications, or stocking supply caches.[21] The large numbers of such groups striking at different times however, gave the war its "around the clock" quality.

Other aspects

Foreign and native regimes

Examples of successful guerrilla warfare against a native regime include the Cuban Revolution and the Chinese Civil War, as well as the Sandinista Revolution which overthrew a military dictatorship in Nicaragua. The many coups and rebellions of Africa often reflect guerrilla warfare, with various groups having clear political objectives and using guerrilla tactics. Examples include the overthrow of regimes in Uganda, Liberia and other places. In Asia, native or local regimes have been overthrown by guerrilla warfare, most notably in Vietnam, China and Cambodia.

Foreign forces intervened in all these countries, but the power struggles were eventually resolved locally.

There are many unsuccessful examples of guerrilla warfare against local or native regimes. These include Portuguese Africa (Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau), Malaysia (then Malaya) during the Malayan Emergency, Bolivia, Argentina, and the Philippines. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), fighting for an independent homeland in the north and east of Sri Lanka, achieved significant military successes against the Sri Lankan military and the government itself for twenty years. It was even able to use these tactics effectively against the Indian Peace Keeping Force sent by India in the mid-1980s, which were later withdrawn for varied reasons, primarily political. The mutual attrition on both sides in the island led to a ceasefire following the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Ethical dimensions

Civilians may be attacked or killed as punishment for alleged collaboration, or as a policy of intimidation and coercion. Such attacks are usually sanctioned by the guerrilla leadership with an eye toward the political objectives to be achieved. Attacks may be aimed to weaken civilian morale so that support for the guerrilla's opponents decreases. Civil wars may also involve deliberate attacks against civilians, with both guerrilla groups and organized armies committing atrocities. Ethnic and religious feuds may involve widespread massacres and genocide as competing factions inflict massive violence on targeted civilian population.

Guerrillas in wars against foreign powers may direct their attacks at civilians, particularly if foreign forces are too strong to be confronted directly on a long term basis. In Vietnam, bombings and terror attacks against civilians were fairly common, and were often effective in demoralizing local opinion that supported the ruling regime and its American backers. While attacking an American base might involve lengthy planning and casualties, smaller scale terror strikes in the civilian sphere were easier to execute. Such attacks also had an effect on the international scale, demoralizing American opinion, and hastening a withdrawal.

In Iraq, most of the deaths since the 2003 US invasion have not been suffered by US troops but by civilians, as warring factions plunged the country into civil war based on ethnic and religious hostilities. (See also: Sectarian war in Iraq) Arguments vary on whether such turmoil will succeed in turning American opinion against the US troop deployment. However, the use of attacks against civilians to create an atmosphere of chaos (and thus political advantage where the atmosphere causes foreign occupiers to withdraw or offer concessions), is well established in guerrilla and national liberation struggles. Claims and counterclaims of the morality of such attacks, or whether guerrillas should be classified as "terrorists" or "freedom fighters" are beyond the scope of this article. See Terrorism and Genocide for a more in-depth discussion of the moral and ethical implications of targeting civilians.

Laws of war

Guerrilleros are in danger of not being recognized as lawful combatants because they may not wear a uniform, (to mingle with the local population), or their uniform and distinctive emblems may not be recognized as such by their opponents. This occurred in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, see Franc-Tireurs.

Article 44, sections 3 and 4 of the 1977 First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, "relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts", does recognize combatants who, because of the nature of the conflict, do not wear uniforms as long as they carry their weapons openly during military operations. This gives non-uniformed guerrilleros lawful combatant status against countries that have ratified this convention. However, the same protocol states in Article 37.1.c that "the feigning of civilian, non-combatant status" shall constitute perfidy and is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions. So is the wearing of enemy uniform, as happened in the Boer War.

Writings

Theories of Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, during the Chinese Civil War, summarized the People's Liberation Army's principles of Revolutionary Warfare in the following points for his troops: The enemy advances, we retreat. The enemy camps, we harass. The enemy tires, we attack. The enemy retreats, we pursue. A common slogan of the time went "Draw back your fist before you strike." This referred to the tactic of baiting the enemy, "drawing back the fist," before "striking" at the critical moment where they are overstretched and vulnerable. Mao made a distinction between Mobile Warfare (yundong zhan) and Guerrilla Warfare (youji zhan), but they were part of an integrated continuum aiming towards a final objective. Mao's seminal work. On Guerrilla Warfare,[22] has been widely distributed and applied, successfully in Vietnam, under military leader and theorist Vo Nguyen Giap. Giap's "Peoples War, Peoples Army"[5] closely follows the Maoist three-stage approach.

Writings of T. E. Lawrence

T. E. Lawrence, best known as "Lawrence of Arabia," introduced a theory of guerrilla warfare tactics in an article he wrote for the Encyclopedia Britannica published in 1938. In that article, he compared guerrilla fighters to a gas. The fighters disperse in the area of operations more or less randomly. They or their cells occupy a very small intrinsic space in that area, just as gas molecules occupy a very small intrinsic space in a container. The fighters may coalesce into groups for tactical purposes, but their general state is dispersed. Such fighters cannot be "rounded up." They cannot be contained. They are extremely difficult to "defeat" because they cannot be brought to battle in significant numbers. The cost in soldiers and material to destroy a significant number of them becomes prohibitive, in all senses, that is physically, economically, and morally. Lawrence describes a non-native occupying force as the enemy (such as the Turks).

Lawrence wrote down some of his theories while ill and unable to fight the Turks in his book The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. There, he reviews von Clausewitz and other theorists of war, and finds their writings inapplicable to his situation. The Arabs could not then inspire fear in their enemy, nor would a pitched battle result in 'the effusion of blood' in other than a Turkish victory.

So instead Lawrence proposed if possible never meeting the enemy, thus giving their soldiers nothing to shoot at, unable to control anything except what ground their rifles could point to. Meanwhile, Lawrence and the Arabs could ride camels into and out of the desert, attacking railroad lines with impunity, avoiding the garrisoned train stations.

Writing of Abdul Haris Nasution

The fullest expression of the Indonesian army’s founding doctrines is found in Abdul Haris Nasution’s 1953 Fundamentals of Guerrilla Warfare.[23] The work is a mix of reproduced strategic directives from 1947-8, Nasution’s theories of guerrilla warfare, his reflections on the period just past (post-Japanese occupation) and the likely crises to come, and outlines of his legal frameworks for military justice and “guerrilla government”. The work contains similar principles to those espoused or practiced by other theorists and practitioners from Michael Collins in Ireland, T. E. Lawrence in the Middle East and Mao in China in the early Twentieth Century, to contemporary insurgents in Afghanistan and Iraq. Nasution willingly shows his influences, frequently referring to some guerrilla activities as "Wingate" actions, quoting Lawrence and drawing lessons from the recent and further past to develop and illustrate his well-thought out arguments. Where the work substantially differs from other theorist/practitioners is that General Nasution was one of the few men to have led both a guerrilla and a counter-guerrilla war. This dual perspective on the realities of ‘people’s war’ leaves the work refreshingly free of the dogmatic hyperbole and ideological contortions of similar revolutionary works from the period and manages to be both brutally direct in the methods it espouses and jarringly honest about the terrible price revolutionary guerrilla war exacts on everyone it comes in contact with, ‘the people’ most of all.[24]

Texts and treatises

Guerrilla tactics were summarized into the Mini-manual of the Urban Guerrilla[25] in 1969 by Carlos Marighella. This text was banned in several countries including the United States. This is probably the most comprehensive and informative book on guerrilla strategy ever published, and is available free online. Texts by Che Guevara[26] and Mao Zedong[22] on guerrilla warfare are also available.

World War II American writings

John Keats wrote about an American guerrilla leader in World War II: Colonel Wendell Fertig, who in 1939 organized a large guerrilla which harassed the Japanese occupation forces on the Philippine Island of Mindanao all the way up to the liberation of the Philippines in 1945. His abilities were later utilized by the United States Army, when Fertig helped found the United States Army Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Others included Col. Aaron Bank and Col. Russell Volckmann. Volckmann, in particular, commanded a guerrilla force which operated out of the Cordillera of Northern Luzon,[27] in the Philippines from the beginning of World War II to its conclusion. He remained in radio contact with US Forces,[28] prior to the invasion of Lingayen Gulf. Finally, there is Brigadier C. Aubrey Dixon, OBE, chief small arms ammunition designer for the British during World War II and a member of the tribunal trying Field Marshal von Manstein.[29]

Counter-guerrilla warfare

Principles

The guerrilla can be difficult to beat, but certain principles of counter-insurgency warfare are well known since the 1950s and 1960s and have been successfully applied.

Classic guidelines

The widely distributed and influential work of Sir Robert Thompson, counter-insurgency expert in Malaysia, offers several such guidelines. Thompson's underlying assumption is that of a country minimally committed to the rule of law and better governance. Some governments, however, give such considerations short shrift, and their counterguerrilla operations have involved mass murder, genocide, starvation and the massive spread of terror, torture and execution. The totalitarian regimes of Hitler are classic examples, as are more modern conflicts in places like Afghanistan. In Afghanistan's anti-Mujahideen war for example, the Soviets implemented a ruthless policy of wastage and depopulation, driving over one third of the Afghan population into exile (over 5 million people), and carrying out widespread destruction of villages, granaries, crops, herds and irrigation systems, including the deadly and widespread mining of fields and pastures. See Wiki article Soviet war in Afghanistan. Many modern countries employ manhunting doctrine to seek out and eliminate individual guerrillas. Elements of Thompson's moderate approach are adapted here:[30]

- The people are the key base to be secured and defended rather than territory won or enemy bodies counted. Contrary to the focus of conventional warfare, territory gained, or casualty counts are not of overriding importance in counter-guerrilla warfare. The support of the population is the key variable. Since many insurgents rely on the population for recruits, food, shelter, financing, and other materials, the counter-insurgent force must focus its efforts on providing physical and economic security for that population and defending it against insurgent attacks and propaganda.

- There must be a clear political counter-vision that can overshadow, match or neutralize the guerrilla vision. This can range from granting political autonomy, to economic development measures in the affected region. The vision must be an integrated approach, involving political, social and economic and media influence measures. A nationalist narrative for example, might be used in one situation, an ethnic autonomy approach in another. An aggressive media campaign must also be mounted in support of the competing vision or the counter-insurgent regime will appear weak or incompetent.

- Practical action must be taken at the lower levels to match the competitive political vision. It may be tempting for the counter-insurgent side to simply declare guerrillas "terrorists" and pursue a harsh liquidation strategy. Brute force however, may not be successful in the long run. Action does not mean capitulation, but sincere steps such as removing corrupt or arbitrary officials, cleaning up fraud, building more infrastructure, collecting taxes honestly, or addressing other legitimate grievances can do much to undermine the guerrillas' appeal.

- Economy of force. The counter-insurgent regime must not overreact to guerrilla provocations, since this may indeed be what they seek to create a crisis in civilian morale. Indiscriminate use of firepower may only serve to alienate the key focus of counterinsurgency- the base of the people. Police level actions should guide the effort and take place in a clear framework of legality, even if under a State of Emergency. Civil liberties and other customs of peacetime may have to be suspended, but again, the counter-insurgent regime must exercise restraint, and cleave to orderly procedures. In the counter-insurgency context, "boots on the ground" are even more important than technological prowess and massive firepower, although anti-guerrilla forces should take full advantage of modern air, artillery and electronic warfare assets.[31]

- Big unit action may sometimes be necessary. If police action is not sufficient to stop the guerrilla fighters, military sweeps may be necessary. Such "big battalion" operations may be needed to break up significant guerrilla concentrations and split them into small groups where combined civic-police action can control them.

- Aggressive mobility. Mobility and aggressive small unit action is extremely important for the counter-insurgent regime. Heavy formations must be lightened to aggressively locate, pursue and fix insurgent units. Huddling in static strongpoints simply concedes the field to the insurgents. They must be kept on the run constantly with aggressive patrols, raids, ambushes, sweeps, cordons, roadblocks, prisoner snatches, etc.

- Ground level embedding and integration. In tandem with mobility is the embedding of hardcore counter-insurgent units or troops with local security forces and civilian elements. The US Marines in Vietnam also saw some success with this method, under its CAP (Combined Action Program) where Marines were teamed as both trainers and "stiffeners" of local elements on the ground. US Special Forces in Vietnam like the Green Berets, also caused significant local problems for their opponents by their leadership and integration with mobile tribal and irregular forces.[32] In Iraq, the 2007 US "surge" strategy saw the embedding of regular and special forces troops among Iraqi army units. These hardcore groups were also incorporated into local neighborhood outposts in a bid to facilitate intelligence gathering, and to strengthen ground level support among the masses.[31]

- Cultural sensitivity. Counter-insurgent forces require familiarity with the local culture, mores and language or they will experience numerous difficulties. Americans experienced this in Vietnam and during the US Iraqi Freedom invasion and occupation, where shortages of Arabic speaking interpreters and translators hindered both civil and military operations.[33]

- Systematic intelligence effort. Every effort must be made to gather and organize useful intelligence. A systematic process must be set up to do so, from casual questioning of civilians to structured interrogations of prisoners. Creative measures must also be used, including the use of double agents, or even bogus "liberation" or sympathizer groups that help reveal insurgent personnel or operations.

- Methodical clear and hold. An "ink spot" clear and hold strategy must be used by the counter-insurgent regime, dividing the conflict area into sectors, and assigning priorities between them. Control must expand outward like an ink spot on paper, systematically neutralizing and eliminating the insurgents in one sector of the grid, before proceeding to the next. It may be necessary to pursue holding or defensive actions elsewhere, while priority areas are cleared and held.

- Careful deployment of mass popular forces and special units. Mass forces include village self-defence groups and citizen militias organized for community defence and can be useful in providing civic mobilization and local security. Specialist units can be used profitably, including commando squads, long range reconnaissance and "hunter-killer" patrols, defectors who can track or persuade their former colleagues like the Kit Carson units in Vietnam, and paramilitary style groups. Strict control must be kept over specialist units to prevent the emergence of violent vigilante style reprisal squads that undermine the government's program.

- The limits of foreign assistance must be clearly defined and carefully used. Such aid should be limited either by time, or as to material and technical, and personnel support, or both. While outside aid or even troops can be helpful, lack of clear limits, in terms of either a realistic plan for victory or exit strategy, may find the foreign helper "taking over" the local war, and being sucked into a lengthy commitment, thus providing the guerrillas with valuable propaganda opportunities as the stream of dead foreigners mounts. Such a scenario occurred with the US in Vietnam, with the American effort creating dependence in South Vietnam, and war weariness and protests back home. Heavy-handed foreign interference may also fail to operate effectively within the local cultural context, setting up conditions for failure.

- Time. A key factor in guerrilla strategy is a drawn-out, protracted conflict, that wears down the will of the opposing counter-insurgent forces. Democracies are especially vulnerable to the factor of time. The counter-insurgent force must allow enough time to get the job done. Impatient demands for victory centered around short-term electoral cycles play into the hands of the guerrillas, though it is equally important to recognize when a cause is lost and the guerrillas have won.

Variants

Some writers on counter-insurgency warfare emphasize the more turbulent nature of today's guerrilla warfare environment, where the clear political goals, parties and structures of such places as Vietnam, Malaysia, or El Salvador are not as prevalent. These writers point to numerous guerrilla conflicts that center around religious, ethnic or even criminal enterprise themes, and that do not lend themselves to the classic "national liberation" template. The wide availability of the Internet has also cause changes in the tempo and mode of guerrilla operations in such areas as coordination of strikes, leveraging of financing, recruitment, and media manipulation. While the classic guidelines still apply, today's anti-guerrilla forces need to accept a more disruptive, disorderly and ambiguous mode of operation.

- "Insurgents may not be seeking to overthrow the state, may have no coherent strategy or may pursue a faith-based approach difficult to counter with traditional methods. There may be numerous competing insurgencies in one theater, meaning that the counterinsurgent must control the overall environment rather than defeat a specific enemy. The actions of individuals and the propaganda effect of a subjective “single narrative” may far outweigh practical progress, rendering counterinsurgency even more non-linear and unpredictable than before. The counterinsurgent, not the insurgent, may initiate the conflict and represent the forces of revolutionary change. The economic relationship between insurgent and population may be diametrically opposed to classical theory. And insurgent tactics, based on exploiting the propaganda effects of urban bombing, may invalidate some classical tactics and render others, like patrolling, counterproductive under some circumstances. Thus, field evidence suggests, classical theory is necessary but not sufficient for success against contemporary insurgencies..."[34]

Current guerrilla conflicts

Present ongoing guerrilla wars, and regions facing guerrilla war activity include:

- Sri Lanka

- Arab-Israeli Conflict

- Uganda

- Zapatista Army of National Liberation, Mexico - have been relatively non-violent since 1994

- India

- Nepal

- Internal conflict in Peru

- Second Chechen War

- ETA in Spain, with the only exception of the first guerrilleros, like Xabier Zumalde El Cabra the Hispanic goat on the mountains refugee, from the first 60's to final 60. Now has a most indiscriminated actions (for example danger actions in urban areas near of militar headquarters of gendarmerie or municipal polices, judges, banks) than the first times against civic-militars, and with the Tiro en la nuca (shoot surprising by the back on the neck).

- FARC in Colombia day to day with more criminals links, with terrorism and drugs to "self-fianance"

- Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan relationated with international terrrorism of Al-Qaida and financied in part by opium and possibly by neighbour countries interested on desestabilize and control the intern politic of Afganistan.

- Darfur Conflict

- Colombian Armed Conflict

- Iran

- Conflict in Iraq

- Kurdish Unrest in Turkey

- Ivorian Civil War ended in 2004 but UNOCI is still handling the rebels who are attacking UN peacekeepers

- Islamic and Communist Insurgencies in the Philippines

- Sudan

- Second Tuareg Rebellion

History

Since classical antiquity, many strategies and tactics were being used to fight foreign occupation that anticipated the modern guerrilla. The Fabian strategy applied by the Roman Republic against Hannibal in the Second Punic War could be considered an early example of guerrilla tactics: After witnessing several disastrous defeats, assassinations and raiding parties, the Romans set aside the typical military doctrine of crushing the enemy in a single battle and initiated a successful, albeit unpopular, war of attrition against the Carthaginians that lasted for 14 years. In expanding their own Empire, the Romans encountered numerous examples of guerrilla resistance to their legions as well. The success of Judas Maccabeus in his rebellion against Seleucid rule was at least partly due to his mastery of irregular warfare.

The victory of the Basque forces against Charlemagne's army in the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, which gave birth to the Medieval myth of Roland, was due to effective use of a guerrilla principles in the mountain terrain of the Pyrenees.[citation needed] Mongols also faced irregulars composed of armed peasants in Hungary after the Battle of Mohi. In the 15th century, Vietnamese leader Le Loi launched a guerrilla war against Chinese.[35] One of the most successful guerrilla wars against the invading Ottomans was led by Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg from 1443 to 1468. In 1443 he rallied Albanian forces and drove the Turks from his homeland. For 25 years Skanderbeg kept the Turks from retaking Albania, which due to its proximity to Italy, could easily have served as a springboard to the rest of Europe.[36] In 1462, the Ottomans were driven back by Wallachian prince Vlad III Dracula. Vlad was unable to stop the Turks from entering Wallachia, so he resorted to guerrilla war, constantly organizing small attacks and ambushes on the Turks.[37] During The Deluge in Poland guerrilla tactics were applied.[38] In the 100 years war between England and France, commander Bertrand du Guesclin used guerrilla tactics to pester the English invaders. The Frisian warlord, folk hero, legendary warrior and freedom fighter Pier Gerlofs Donia fought a guerrilla against Philip I of Castile and after him against Charles V.

During the Dutch Revolt of the 16th century, the Geuzen waged a guerrilla war against the Spanish Empire.[39] During the Scanian War, a pro-Danish guerrilla group known as the Snapphane fought against the Swedes. In 17th century Ireland, Irish irregulars called tories and rapparees used guerrilla warfare in the Irish Confederate Wars and the Williamite war in Ireland. The Finns guerrillas, sissis, fought against Russian occupation troops in the Great Northern War 1710-1721. The Russians retaliated brutally on civilian populace; the period is called Isoviha (Grand Hatred) in Finland.

Vendéan Counter-Revolution

From 1793-1796 a revolt broke out against the French Revolution by Catholic royalists in the Department of the Vendée. This movement was intended to oppose the persecution endured by the Roman Catholic Church in revolutionary France (see Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution#The Revolution and the Church) and ultimately to restore the monarchy. Though ill-equipped and untrained in conventional military tactics, the Vendéan counter-revolution, known as the “Royal Catholic Army,” relied heavily on guerrilla tactics, taking full advantage of their intimate knowledge of the marsh filled, heavily forested countryside. Though the Revolt in the Vendée was eventually “pacified” by government troops, their successes against the larger, better equipped republican army were notable.

Works such as “La Vendée” by Anthony Trollope (http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext04/8vend10.txt ), G.A. Henty’s “No Surrender! A Tale of Rising in the Vendée” (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/20091/20091-h/20091-h.htm) detail the history of the revolt.

Napoleonic Wars

In the Napoleonic Wars many of the armies lived off the land. This often led to some resistance by the local population if the army did not pay fair prices for produce they consumed. Usually this resistance was sporadic, and not very successful, so it is not classified as guerrilla action. There are three notable exceptions, though:

- The rebellion of 1809 in the Tyrol led by Andreas Hofer.

- In Napoleon's invasion of Russia of 1812 two actions could be seen as initiating guerrilla tactics. The burning of Moscow after it had been occupied by Napoleon's Grand Army, depriving the French of shelter in the city, resembled guerrilla action insofar as it was an attack on the available resources rather than directly on the troops (and insofar as it was a Russian action rather than an inadvertent consequence of nineteenth-century troops' camping in a largely abandoned city of wooden buildings). In a different sense, the imperial command that the Russian serfs should attack the French resembled guerrilla tactics in its reliance on partisans rather than army regulars. This did not so much spark a guerrilla war as encourage a revengeful slaughter of French deserters by Russian peasants.[40]

- In the Peninsular War Spanish guerrillas tied down tens of thousands of French troops and killed hundreds of thousands. The continual losses of troops caused Napoleon to describe this conflict his "Spanish ulcer". This was one of the most successful partisan wars in history and was where the word guerrilla was first used in this context. The Oxford English Dictionary lists Wellington as the oldest known source, speaking of "Guerrillas" in 1809. Poet William Wordsworth showed a surprising early insight into guerrilla methods in his pamphlet on the Convention of Cintra:

- "It is manifest that, though a great army may easily defeat or disperse another army, less or greater, yet it is not in a like degree formidable to a determined people, nor efficient in a like degree to subdue them, or to keep them in subjugation–much less if this people, like those of Spain in the present instance, be numerous, and, like them, inhabit a territory extensive and strong by nature. For a great army, and even several great armies, cannot accomplish this by marching about the country, unbroken, but each must split itself into many portions, and the several detachments become weak accordingly, not merely as they are small in size, but because the soldiery, acting thus, necessarily relinquish much of that part of their superiority, which lies in what may be called the engineer of war; and far more, because they lose, in proportion as they are broken, the power of profiting by the military skill of the Commanders, or by their own military habits. The experienced soldier is thus brought down nearer to the plain ground of the inexperienced, man to the level of man: and it is then, that the truly brave man rises, the man of good hopes and purposes; and superiority in moral brings with it superiority in physical power.” (William Wordsworth: Selected Prose, Penguin Classics 1988, page 177-8.)

Others

- In 1848, both The Nation and The United Irishman advocated guerrilla warfare to overthrow English rule in Ireland, though no actual warfare took place.

- The Poles and Lithuanians used guerrilla warfare during the January Uprising of 1863-1865, against Tsarist Russia.

- In the 19th century, peoples of the Balkans used guerrilla tactics to fight the Ottoman empire.

Irish War of Independence and Civil War

The wars between Ireland and the British state have been long, and over the centuries have covered the full spectrum of the types of warfare. The Irish fought the first successful 20th century war of independence against the British Empire and the United Kingdom. After the military failure of the Easter Rising in 1916, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) resorted to guerrilla tactics involving both urban guerrilla warfare and flying columns in the countryside during the Irish War of Independence of 1919 to 1921. The chief IRA commanders in the localities during this period were Tom Barry, Dan Breen, Liam Lynch, Seán Mac Eoin, and Tom Maguire.

The IRA guerrilla was of considerable intensity in parts of the country, notably in Dublin and in areas such as Cork, Kerry and Mayo in the south and west. Despite this, the Irish fighters were never in a position to either hold territory or take on British forces in a conventional manner. Even the largest engagements of the conflict, such as the Kilmichael Ambush or Crossbarry Ambush constituted mere skirmishes by the standards of a conventional war. Another aspect of the war, particularly in the north-eastern part of the province of Ulster, was communal violence. The Unionist majority there, who were largely Protestant and loyal to Britain were granted control over the security forces there, in particular the Ulster Special Constabulary and used them to attack the Nationalist (and largely Catholic) population in reprisal for IRA actions. Elsewhere in Ireland, where Unionists were in a minority (as in the Dunmanway Massacre in Cork), they were sometimes attacked by the IRA for aiding the British forces. The extent to which the conflict was an inter-communal one as well as war of national liberation is still strongly debated in Ireland. The total death toll in the war came to a little over 2000 people.

By mid 1921, the military and political costs of maintaining the British security forces in Ireland eventually proved too heavy for the British government. In July 1921, the UK government agreed to a truce with the IRA and agreed to meet representatives of the Irish First Dail, who since the 1918 General Election held seventy-three of the one hundred and five parliamentary seats for the island. Negotiations led to a settlement, the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It created the Irish Free State of 26 counties as a dominion within the British Empire; the other 6 counties remained part of the UK as Northern Ireland.

Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Army split into pro- and anti-Treaty factions with the Anti-Treaty IRA forces losing the Irish Civil War (1922-23) which followed. The partition of Ireland laid the seeds for the later Troubles. The Irish Civil War is a striking example of the failure of guerrilla tactics when used against a relatively popular native regime. Following their failure to hold fixed positions against an Irish Free State offensive in the summer of 1922, the IRA re-formed "flying columns" and attempted to use the same tactics they had successfully used against the British. However, against Irish troops, who knew them and the terrain and faced with the hostility of the Roman Catholic Church and the majority of Irish nationalist opinion, they were unable to sustain their campaign. In addition, the Free State government, confident of its legitimacy among the Irish population, sometimes used more ruthless and effective measures of repression than the British had felt able to employ. Whereas the British executed 14 IRA men in 1919-1922, the Free State executed 77 anti-treaty prisoners officially and its troops killed another 150 prisoners or so in the field (see Executions during the Irish Civil War). The Free State also interned 12,000 republicans, compared with the British figure of 4,500. The last anti-Treaty guerrillas abandoned their military campaign against the Free State after nine months in March 1923.

World War I

In a successful campaign in German East Africa, the German commander Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck fought against the numerically superior allied forces. Even though he was cut off from Germany and had few Germans under his command (most of his fighters were African askaris), he won multiple victories during the East Africa Campaign and managed to exhaust and trouble the Allies; he was undefeated up until his acceptance of a cease-fire in Northern Rhodesia three days after the end of the war in Europe. He returned to Germany as a hero.

A major guerrilla war was fought by the Arabs against the Ottoman Turks during the Arab Revolt (1916–1918).

Another guerrilla war opposed the German Occupation of Ukraine in 1918 and partisan and guerrilla forces fought against both the Bolsheviks and the Whites during the Russian Civil War. This fighting continued into 1921 in Ukraine, in Tambov province, and in parts of Siberia. Other guerrillas opposed the Japanese occupation of the Russian Far East.

World War II

Many clandestine organizations (often known as resistance movements) operated in the countries occupied by German Reich during the Second World War. These organizations began forming as early as 1939 when, after the defeat of Poland, the members of what would become the Polish Home Army began to gather. Other clandestine organizations operated in Denmark, Belgium, Norway, France (Resistance), France (Maquis), Czechoslovakia, Slovakia, Yugoslavia (Royalist Chetniks), Yugoslavia (Partisans), Soviet Union, Italy, and Greece. Many of these organizations received help from the British operated Special Operations Executive (SOE) which along with the commandos was initiated by Winston Churchill to "set Europe ablaze." The SOE was originally designated as 'Section D' of MI6 but its aid to resistance movements to start fires clashed with MI6's primary role as an intelligence-gathering agency. When Britain was under threat of invasion, SOE trained Auxiliary Units to conduct guerrilla warfare in the event of invasion. Even the Home Guard were trained in guerrilla warfare in the case of invasion of England. Osterly Park was the first of 3 such schools established to train the Home Guard.

Not only did SOE help the resistance to tie down many German units as garrison troops, so directly aiding the conventional war effort, but also guerrilla incidents in occupied countries were useful in the propaganda war, helping to repudiate German claims that the occupied countries were pacified and broadly on the side of the Germans. Despite these minor successes, many historians believe that the efficacy of the European resistance movements has been greatly exaggerated in popular novels, films and other media.[citation needed]

Contrary to popular belief, in the Western and Southern Europe the resistance groups were only able to seriously counter the German in areas that offered the protection of rugged terrain.[citation needed] In relatively flat, open areas, such as France, the resistance groups were all too vulnerable to decimation by German regulars and pro-German collaborators. Only when operating in concert with conventional Allied units were the resistance groups to prove indispensable.[citation needed]

All the clandestine resistance movements and organisations in the occupied Europe were dwarfed by the partisan warfare that took place on the vast scale of the Eastern Front combat between Soviet partisans and the German Reich forces. The strength of the partisan units and formations can not be accurately estimated, but in Belorussia alone is thought to have been in excess of 300,000. [citation needed]This was a planned and closely coordinated effort by the STAVKA which included insertion of officers and delivery of equipment, as well as coordination of operational planning with the regular Red Army forces such as Operation Concert in 1943 (commenced 19 September) and the massive sabotage of German logistics in preparation for commencement of Operation Bagration in the summer of 1944.[42]

When the U.S. entered the war, the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) co-operated and enhanced the work of SOE as well as working on its own initiatives in the Far East.

Post World War II

After World War II, during the 1940s and 1950s, thousands of fighters in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (see Forest Brothers) participated in unsuccessful guerrilla warfare against Soviet occupation.[43] In Lithuania guerrilla warfare was massive until 1958.

In the late 1960s the Troubles began again in Northern Ireland. They had their origins in the partition of Ireland during the Irish War of Independence. They came to an end with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. The violence was characterised by an armed campaign against the British presence in Northern Ireland by the Provisional Irish Republican Army, British counter-insurgency policy, and attacks on civilians by both loyalists and republicans. There were also allegations of collusion between loyalist paramilitaries and British security forces, and to a lesser extent, republicans and both British and Irish security forces.[44][45][46][47][48]

Although both loyalist and republican paramilitaries carried out terrorist atrocities against civilians which were often tit-for-tat, a case can be made for saying that attacks such as the Provisional IRA carried out on British soldiers at Warrenpoint in 1979 was a well planned guerrilla ambush.[49] However media coverage of the attack was overshadowed by their killing of Louis Mountbatten and three other people on a fishing boat in Sligo on the same day. The Provisional Irish Republican Army, Loyalist paramilitaries and various anti-Good Friday Agreement splinter-groups could be called guerrillas but are usually called terrorists by governments of both the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland governments. The news media such as the BBC and CNN will often use the term "gunmen" as in "IRA gunmen"[50] or "Loyalist gunmen".[51] Since 1995 CNN also uses guerrilla as in "IRA guerrilla" and "Protestant guerrilla".[52] Reuters, in accordance with its principle of not using the word terrorist except in direct quotes, refers to "guerrilla groups".[53]

Europe since 2000

The Greek Marxist 17 November disbanded around 2002 following the capture and imprisonment of much of its leadership.

Currently, the National Front for the Liberation of Corsica (FLNC) continues to exist.

The ongoing war between pro-independence groups in Chechnya and the Russian government is currently the most active guerrilla war in Europe. Most of the incidents reported by the Western news media are very gory terrorist acts against Russian civilians committed by Chechen separatists outside Chechnya. However, within Chechnya the war has many of the characteristics of a classic guerrilla war. See the article History of Chechnya for more details.

In Northern Ireland, the Real Irish Republican Army and the Continuity Irish Republican Army, two small, radical splinter groups who broke with the Provisional Irish Republican Army, continue to exist. They are dwarfed in size by the size of the Provisional IRA and have been less successful in terms of both popularity among Irish republicans and guerrilla activity: The Continuity IRA has failed to carry out any killings, while the Real IRA's only successful strikes was the 1998 Omagh Bombing, which killed 29 civilians, and a booby trap torch bomb in Belfast, which killed a British Army soldier.

American Revolutionary War

While the American Revolutionary War is often thought of as a guerrilla war, guerrilla tactics were uncommon, and almost all of the battles involved conventional set-piece battles. Some of the confusion may be because Generals George Washington and Nathanael Greene successfully used a strategy of harassment and progressively grinding down British forces instead of seeking a decisive battle, in a classic example of asymmetric warfare. Nevertheless the theater tactics used by most of the American forces were those of conventional warfare. One of the exceptions was in the south, where the brunt of the war was upon militia forces who fought the enemy British troops and their Loyalist supporters, but used concealment, surprise, and other guerrilla tactics to much advantage. General Francis Marion of South Carolina, who often attacked the British at unexpected places and then faded into the swamps by the time the British were able to organize return fire, was named by them The Swamp Fox. However, even in the south, most of the major engagements were set-piece battles of conventional warfare. However the guerrilla tactics in the south were a key factor in the prevention of British reinforcement to the north, and that was a decisive factor in the outcome of the war. See also Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, for another American Revolutionary War example.

American Civil War

Irregular warfare in the American Civil War followed the patterns of irregular warfare in 19th century Europe. Structurally, irregular warfare can be divided into three different types conducted during the Civil War: 'People's War', 'partisan warfare', and 'raiding warfare'. The concept of 'People's war,' first described by Clausewitz in On War, was the closest example of a mass guerrilla movement in the era. In general, this type of irregular warfare was conducted in the hinterland of the Border States (Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and northwestern Virginia), and was marked by a vicious neighbor against neighbor quality. One such example was the opposing irregular forces operating in Missouri and northern Arkansas from 1862 to 1865, most of which were pro-Confederate or pro-Union in name only and preyed on civilians and isolated military forces of both sides with little regard of politics. From these semi-organized guerrillas, several groups formed and were given some measure of legitimacy by their governments. Quantrill's Raiders, who terrorized pro-Union civilians and fought Federal troops in large areas of Missouri and Kansas, was one such unit. Another notorious unit, with debatable ties to the Confederate military, was led by Champ Ferguson along the Kentucky-Tennessee border. Ferguson became one of the only figures of Confederate cause to be executed after the war. Dozens of other small, localized bands terrorized the countryside throughout the border region during the war, bringing total war to the area that lasted until the end of the Civil War and, in some areas, beyond.

Partisan warfare, in contrast, more closely resembles Commando operations of the 20th century. Partisans were small units of conventional forces, controlled and organized by a military force for operations behind enemy lines. The 1862 Partisan Ranger Act passed by the Confederate Congress authorized the formation of these units and gave them legitimacy, which placed them in a different category than the common 'bushwhacker' or 'guerrilla'. John Singleton Mosby formed a partisan unit which was very effective in tying down Federal forces behind Union lines in northern Virginia in the last two years of the war.

Lastly, deep raids by conventional cavalry forces were often considered 'irregular' in nature. The "Partisan Brigades" of Nathan Bedford Forrest and John Hunt Morgan operated as part of the cavalry forces of the Confederate Army of Tennessee in 1862 and 1863. They were given specific missions to destroy logistical hubs, railroad bridges, and other strategic targets to support the greater mission of the Army of Tennessee. By mid-1863, with the destruction of Morgan's raiders during the Great Raid of 1863, the Confederacy conducted few deep cavalry raids in the latter years of the war, mostly because of the losses in experienced horsemen and the offensive operations of the Union army. Federal cavalry conducted several successful raids during the war but in general used their cavalry forces in a more conventional role. A good exception was the 1863 Grierson's Raid, which did much to set the stage for General Ulysses S. Grant's victory during the Vicksburg Campaign.

Federal counter-guerrilla operations were very successful in preventing the success of Confederate guerrilla warfare. In Arkansas, Federal forces used a wide variety of strategies to defeat irregulars. These included the use of Arkansas Unionist forces as anti-guerrilla troops, the use of riverine forces such as gunboats to control the waterways, and the provost marshal military law enforcement system to spy on suspected guerrillas and to imprison those captured. Against Confederate raiders, the Federal army developed an effective cavalry themselves and reinforced that system by numerous blockhouses and fortification to defend strategic targets.

However, Federal attempts to defeat Mosby's Partisan Rangers fell short of success because of Mosby's use of very small units (10–15 men) operating in areas considered friendly to the Rebel cause. Another regiment known as the "Thomas Legion," consisting of white and anti-Union Cherokee Indians, morphed into a guerrilla force and continued fighting in the remote mountain back-country of western North Carolina for a month after Lee's surrender at Appomattox. That unit was never completely suppressed by Union forces, but voluntarily ceased hostilities after capturing the town of Waynesville on May 10 1865.

In the late 20th century several historians have focused on the non-use of guerrilla warfare to prolong the war. Near the end of the war, there were those in the Confederate government, notably Jefferson Davis who advocated continuing the southern fight as a guerrilla conflict. He was opposed by generals such as Robert E. Lee who ultimately believed that surrender and reconciliation were better than guerrilla warfare.

See also Bushwhackers (Union and Confederate) and Jayhawkers (Union).

South African War

Guerrilla tactics were used extensively by the forces of the Boer republics in the First and Second Boer Wars in South Africa (1880-1881; 1899-1902) against the invading British Army. In the First Boer War, the Boer commandos wore their everyday dull-coloured farming clothes. The Boers relied more on stealth and speed than discipline and formation and, being expert marksmen using smokeless ammunition, the Boer were able to easily snipe at British troops from a distance. So the British Army relaxed their close-formation tactics. The British Army had changed to Khaki uniforms, first used by the British Indian Army, a decade earlier, and officers were soon ordered to dispense with gleaming buttons and buckles which made them conspicuous to snipers.

In the third phase of the Second Boer War, after the British defeated the Boer armies in conventional warfare and occupied their capitals of Pretoria and Bloemfontein, Boer commandos reverted to mobile warfare. Units led by leaders such as Jan Smuts and Christian de Wet harassed slow-moving British columns and attacked railway lines and encampments. The Boers were almost all mounted and possessed long range magazine loaded rifles. This gave them the ability to attack quickly and cause many casualties before retreating rapidly when British reinforcements arrived. In the early period of the guerrilla war, Boer commandos could be very large, containing several thousand men and even field artillery. However, as their supplies of food and ammunition gave out, the Boers increasingly broke up into smaller units and relied on captured British arms, ammunition, and uniforms.

To counter these tactics, the British under Kitchener interned Boer civilians into concentration camps and built hundreds of blockhouses all over the Transvaal and Orange Free State. Kitchener also enacted a scorched earth policy, destroying Boer homes and farms. Eventually, the Boer guerrillas surrendered in 1902, but the British granted them generous terms in order to bring the war to an end. This showed how effective guerrilla tactics could be in extracting concessions from a militarily more powerful enemy.

Second Sino-Japanese War

Despite a common misconception, both Nationalist and Communist forces maintained active underground resistance in Japanese-occupied areas during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Even before the outbreak of total war in 1937, partisans were already present in Manchuria hampering Japan's occupation of the region. After the initial phases of the war, when large swaths of the North China Plain rapidly fell to the Japanese, underground resistance, supported by either Communist sympathizers or composed of disguised Nationalist soldiers, would soon rise up to combat the garrison forces. They were quite successful, able to sabotage railroad routes and ambush reinforcements. Many major campaigns, such as the four failed invasions of Changsha, were caused by overly-stretched supply lines, lack of reinforcements, and ambushes by irregulars. The Communist cells, many having decades of prior experience in guerrilla warfare against the Nationalists, usually fared much better, and many Nationalist underground groups were subsequently absorbed into Communist ones. Usually in Japanese-occupied areas, the IJA only controlled the cities and railroad routes, with most of them countryside either left alone or with active guerrilla presence. The People's Republic of China has emphasized their contribution to the Chinese war effort, going as far to say that in addition to a "overt theatre", which in many cases they deny was effective, there was also a "covert theatre", which they claim did much to stop the Japanese advance.

Israel and the West Bank & Gaza

European Jews fleeing from anti-Semitic violence (especially Russian pogroms) immigrated in increasing numbers to Palestine. When the British restricted Jewish immigration to the region (see White Paper of 1939), Jewish immigrants began to use guerrilla warfare against the British for two purposes: to bring in more Jewish refugees, and to turn the tide of British sentiment at home. Jewish groups such as the Lehi and the Irgun - many of whom had experience in the Warsaw Ghetto battles against the Nazis, fought British soldiers whenever they could, including the bombing of the King David Hotel.

The Jewish forces were composed of spontaneous groups of civilians working without formal military structure, fighting the British Empire, which had just emerged victorious from World War II. Some of these groups were amalgamated into the Israel Defence Force and subsequently fought in the 1948 War of Independence.

Latin America

In the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1920, the populist revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata employed the use of predominantly guerrilla tactics. His forces, composed entirely of peasant farmers turned soldiers, wore no uniform and would easily blend into the general population after an operation's completion. They would have young soldiers, called "dynamite boys", hurl cans filled with explosives into enemy barracks, and then a large number of lightly armed soldiers would emerge from the surrounding area to attack it. Although Zapata's forces met considerable success, his strategy backfired as government troops, unable to distinguish his soldiers from the civilian population, waged a broad and brutal campaign against the latter.

In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Latin America had several urban guerrilla movements whose strategy was to destabilize regimes and provoke a counter-reaction by the military. The theory was that a harsh military regime would oppress the middle classes who would then support the guerrillas and create a popular uprising.

While these movements did destabilize governments, such as Argentina, Uruguay, Guatemala, and Peru to the point of military intervention, the military generally proceeded to completely wipe out the guerrilla movements, usually committing several atrocities among both civilians and armed insurgents in the process.

Several other left-wing guerrilla movements, sometimes backed by Cuba, attempted to overthrow US-backed governments or right-wing military dictatorships. US-backed Contra guerrillas attempted to overthrow the left-wing elected Sandinista government of Nicaragua, though most of these groups should be considered mercenary juntas rather than rooted guerrillas. The Sandinista Revolution saw the involvement of Women and the Armed Struggle in Nicaragua.

Jammu and Kashmir

Jammu and Kashmir has been disputed between both India and Pakistan. The territory has been disputed since the Indo-Pakistani Partition in 1947. Some militants fight for an independent Kashmiri state, while others backed by the Pakistan Government wish to annex parts of Jammu and Kashmir into Pakistani-Administered Kashmir.

Vietnam War

Within the United States, the Vietnam War is commonly thought of as a guerrilla war. However, this is a simplification of a much more complex situation which followed the pattern outlined by Maoist theory.

The National Liberation Front (NLF), drawing its ranks from the South Vietnamese peasantry and working class, used guerrilla tactics in the early phases of the war. However, by 1965 when U.S. involvement escalated, the National Liberation Front was in the process of being supplanted by regular units of the North Vietnamese Army.

The NVA regiments organized along traditional military lines, were supplied via the Ho Chi Minh trail rather than living off the land, and had access to weapons such as tanks and artillery which are not normally used by guerrilla forces. Furthermore, parts of North Vietnam were "off-limits" by American bombardment for political reasons, giving the NVA personnel and their material a haven that does not usually exist for a guerrilla army.

Over time, more of the fighting was conducted by the North Vietnamese Army and the character of the war become increasingly conventional. The final offensive into South Vietnam in 1975 was a mostly conventional military operation in which guerrilla warfare played a minor, supporting role.

The Cu Chi Tunnels (Ðịa đạo Củ Chi) was a major base for guerrilla warfare during the Vietnam War. Located about 60 km northwest of Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), the Viet Cong (NLF) used the complex system tunnels to hide and live during the day and come up to fight at night.

Despite the aggressiveness of the Vietnamese forces, the VietCong failed to achieve their objective. The defeat of the VietCong outlined the flaws of large scale guerrilla warfare over an extended time. These lessons were later exploited by SAS and Delta Force units during the Gulf War who worked in small teams instead of armies.