Howard Stern

Howard Stern | |

|---|---|

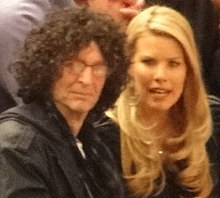

Howard Stern in May 2012 | |

| Born | Howard Allan Stern January 12, 1954 |

| Alma mater | Boston University |

| Occupation(s) | Radio and television personality, producer, author, actor, photographer |

| Years active | 1975–present |

| Political party | Libertarian during the 1994 New York gubernatorial election campaign |

| Spouse(s) | Alison Berns (1978–2001; divorced; 3 children) Beth Ostrosky (2008–present) |

| Website | www |

Howard Allan Stern (born January 12, 1954) is an American radio and television personality, producer, author, actor, and photographer. He is best known for his radio show, which was nationally syndicated from 1986 to 2005. Stern has been exclusive to Sirius XM Radio since 2006. Stern wished to pursue a radio career since the age of five. While at Boston University, he worked at the campus station WTBU before a brief stint at WNTN in Newton, Massachusetts. He developed his on-air personality when he landed positions at WRNW in Briarcliff Manor, WCCC in Hartford, Connecticut, and WWWW in Detroit, Michigan. In 1981, he paired with his current newscaster and co-host Robin Quivers at WWDC in Washington, D.C., before a stint at WNBC in New York City until his firing in 1985.

In 1985, Stern moved to WXRK in New York City and became one of the most popular radio personalities in America. He became the first to have the number one morning radio show in New York and Los Angeles simultaneously and won numerous awards, including winning Billboard’s Nationally Syndicated Air Personality of the Year award eight times. Stern became the most-fined radio host after the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued fines totaling $2.5 million to station licensees for content that it deemed indecent. In 2004, Stern signed a deal with Sirius worth $500 million, making him one of the highest-paid figures in radio history.[1] Stern was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2012.[2]

Stern describes himself as the "King of All Media" for his successes outside radio. He has hosted and produced numerous late night television shows, pay-per-view events, and home videos. He embarked on a five-month political campaign for Governor of New York in 1994. His two books, Private Parts (1993) and Miss America (1995), entered the The New York Times Best Seller list at number one. The former was made into a biographical comedy film in 1997, in which Stern and his radio show staff play themselves. It topped the US box office chart and grossed $41.2 million domestically. Stern performs on its soundtrack, which charted at number one on the Billboard 200. Stern's photography has been featured in numerous magazines including Hamptons and WHIRL. He has served as a judge on America's Got Talent since 2012.

Early life

Howard Allan Stern was born on January 12, 1954. His parents, Bernard and Ray (née Schiffman) Stern, lived in the Jackson Heights neighborhood of Queens, New York City, US.[3] Both are Jewish with Austro-Hungarian and Polish ancestry respectively.[4][5][6] Ray was a homemaker and an inhalation therapist,[7][8] and Ben was a co-owner of Aura Recording Inc., a recording studio in Manhattan where cartoons and commercials were produced.[9] Ben was also an engineer at WHOM, a radio station in Manhattan.[9] Stern describes Ellen, his older sister by four years, as the "complete opposite" of himself; "she's very quiet", he says. [10]

In 1955, the family moved to the hamlet of Roosevelt, New York on Long Island.[11] Stern attended Washington-Rose Elementary School[12] followed by Roosevelt Junior-Senior High School.[12] At the age of five, Stern developed an interest in pursuing a career in radio.[13] He recalls not listening to much radio as a youngster, but cites Bob Grant[14] and Brad Candrall[15] as early influences. When he made occasional visits to his father's recording studio, Stern witnessed "some of the great voice guys" including Wally Cox, Don Adams, and Larry Storch at work[15][16] which influenced him to talk on the air than play music.[17] When Roosevelt became a predominantly black area in the 1960s, Stern remembered just "a handful of white kids left" in his school when he reached the seventh grade.[18] He was also beaten numerous times by black pupils.[18] In June 1969, the family moved to the nearby village of Rockville Centre, and Stern transferred to South Side High School.[19][failed verification] The school's yearbook lists Stern's sole student activity, membership of the Key Club.[20]

In 1972, Stern began his first two of four years at Boston University at its College of Basic Studies.[21] In his second year, Stern visited the campus radio station WTBU and played music, read the news, and hosted interviews.[21] Stern later co-hosted a comedy program with three fellow students called The King Schmaltz Bagel Hour, which was cancelled during its first broadcast for a sketch named "Godzilla Goes to Harlem".[22] Stern gained admission to the university's School of Public Communications in 1974.[23] He then worked for a diploma at the Radio Engineering Institute of Electronics in Fredericksburg, Virginia, which earned him a first class radio-telephone operator license, a certificate required for all radio broadcasters at the time granted by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).[24][25] Stern then worked in his first professional radio job from August to December 1975 at WNTN in Newton, Massachusetts, doing air shifts and newscasting, and undertaking production duties.[26] For the next six months he taught students basic electronics in preparation for their FCC exams.[26] Stern graduated magna cum laude in communications in May 1976.[21][27] In the past he has funded a scholarship at the university.[28]

Career

1976–81: Early radio career

In his search for radio work following his graduation, Stern declined an offer to work evenings at WRNW, a progressive rock station in Briarcliff Manor, New York.[29] He became unsure of his talent and questioned his future as a professional in the industry. He said, "I freaked out. I got real nervous that I wasn't good enough".[29] Stern accepted a marketing role at Benton & Bowles, a New York advertising agency, which he soon "quit without giving notice". He lasted three hours in his new position in the creative team before he was fired "because their personnel department realized that I was the guy who just quit."[29] Stern then worked in Queens, New York selling radio commercial time to companies. "All of a sudden", he writes, "I realized I had turned down a job in radio". With encouragement from Berns, he contacted WRNW for work and agreed to work cover shifts in late December 1976.[26][30] Stern was hired full-time, working a four-hour midday shift for six days a week on a $96 weekly salary.[24] He subsequently became the station's production and program director for an increased salary of $250.[26][31] To save money, Stern rented a room in a monastery in Armonk, New York.[32]

In 1979, Stern spotted an advertisement in Radio & Records for a "wild, fun morning guy" at rock station WCCC in Hartford, Connecticut.[33] He submitted a more outrageous audition tape featuring Robert Klein and Cheech and Chong records with flatulence routines and one-liners.[34] Stern was hired, for the same salary, but worked a more intense schedule. After four hours on the air, he voiced and produced commercials for another four. On Saturdays, following a six-hour show, he did production work for the next three. As the station's public affairs director, he also hosted a Sunday morning public affairs show which he favored above playing records.[35] "That show represented what I wanted to do on radio more than anything", Stern recalled. "Take the average guy and dissect what he does".[36] In the summer of the 1979 energy crisis, Stern urged listeners to a two-day boycott of Shell Oil Company, a stunt which attracted media attention.[37] It was at WCCC where Stern met Fred Norris, the overnight disc jockey, who has been Stern's writer and producer since 1981.[38] According to news reporter and author Paul Colford, Stern was influenced by listening to tapes of Steve Dahl sent from Chicago by a friend of the chief engineer at WCCC.[39] In early 1980, Stern left WCCC after he was denied a pay increase.[40]

On April 21, 1980[19] Stern began a new morning position at WWWW, a rock station in Detroit, Michigan after management praised Stern's audition tape during their search for a new morning man.[41] Stern was determined to be more open on the air, "to cut down the barriers ... strip down all the ego ... and be totally honest" to his audience.[42] However, the station struggled to compete with the city's three more popular rock stations. By January 1981, when Stern's quarterly Arbitron ratings showed no signs of a strong audience, the station changed to a country music format, much to Stern's annoyance. He lasted two weeks on the air as "Hopalong Howie" before his departure.[43] He declined offers to work at WXRT in Chicago and CHUM in Toronto, Canada.[44][45] During his time in Detroit, Stern received a Billboard award for "Album-Oriented Rock Personality of the Year For a Major Market" and the Drake-Chenault "Top Five Talent Search" title.[44][46]

1981–85: Washington, D.C., and WNBC New York

Following his exit from Detroit, Stern moved to Washington, D.C., to host mornings at rock station WWDC on March 2, 1981.[47][48] Feeling determined to develop his show further, he looked for a co-worker with a sense of humor to riff with on news and current events.[49] The station then paired Stern with Robin Quivers, a newscaster and consumer affairs reporter from WFBR in Baltimore.[50] Quivers at first thought she "would come in and do the news ... but it wasn't that way" because Stern "wanted someone to play off of ... he wanted a real live person there with him".[51] The move was a success; by January 1982 Stern had the second highest rated morning show in the area despite the content restrictions enforced by the station management.[52][53] Impressed with his fast rise, NBC approached Stern with an offer to work afternoons at WNBC in New York City. After he signed a five-year contract worth $1 million in March 1982,[54] his relationship with WWDC management worsened,[55] which resulted in the termination of his contract on June 25, 1982. He had more than tripled the station's morning ratings during his tenure.[56] The Washingtonian magazine named Stern the area's best disc jockey.[57] During this time Stern released a song parody album named 50 Ways to Rank Your Mother which was re-released on CD in November 1994 under the title Unclean Beaver.[58]

On April 2, 1982, NBC Magazine aired a news report on "shock radio" by Douglas Kiker that featured Stern.[59] The piece caused NBC executives to discuss the possible withdrawal of Stern's contract, though Stern began his afternoon program in September 1982[60] with management closely monitoring the show and advising Stern to avoid sexual and religious discussions.[61] In his first month, Stern was suspended for several days for "Virgin Mary Kong", a segment featuring a video game where a group of men pursued the Virgin Mary around a singles bar in Jerusalem.[59] The station also hired an attorney to operate a "dump button" that could cut Stern off the microphone should potentially offensive areas be discussed. This became the task of program director Kevin Metheny, who Stern nicknamed "Pig Virus".[59]

In 1985, after hiring his new agent Don Buchwald, Stern signed a five-year contract with WNBC to continue his radio show. Despite management's restrictions, Stern's popularity increased. On May 21, 1984, he made his debut appearance on Late Night with David Letterman and was featured in People magazine, increasing his national exposure.[19] In May 1985, Stern claimed the highest ratings at WNBC in four years with a 5.7% market share.[62] In a sudden turn of events, Stern and Quivers were fired for what management termed "conceptual differences" regarding the show on September 30, 1985.[63] Program director John Hayes explained: "Over the course of time we made a very conscious effort to make Stern aware that certain elements of the program should be changed ... I don't think it's appropriate to say what those specifics were".[64] Though Stern was not told whose decision it was, in 1992 he believed that Thornton Bradshaw, chairman of RCA who owned WNBC, heard his "Bestiality Dial-a-Date" segment that aired ten days prior and ordered him to be fired.[61] Stern and Quivers kept in touch with their audience by booking dates at clubs with a live stage show.[61]

1985–92: WXRK New York and early television and video projects

Stern declined offers to work in Los Angeles, including a payment of $50,000 from NBC if he moved.[65] He wished to stay in New York to "kick NBC's ass".[32] He signed a five-year contract with Infinity Broadcasting worth an estimated $500,000[66] to host afternoons on its rock station WXRK from November 18, 1985.[63] Determined to beat Imus and WNBC in the ratings, Stern moved to the morning slot in February 1986. The show entered national syndication on August 18 that year when WYSP in Philadelphia began to simulcast the program.[63]

Stern's first venture into television began in 1987 when the Fox network sought a replacement for The Late Show, a late-night talk show hosted by Joan Rivers. Stern agreed to record five one hour pilots in May 1987 at the approximate cost of $400,000. Stern picked guitarist Leslie West as band leader and comedian Steve Rossi as his announcer.[67] Following tests among focus groups, the show was never picked up; one Fox executive described the pilots as "poorly produced", "in poor taste", and "boring".[68] Stern went on to host his first pay-per-view event, Howard Stern's Negligeé and Underpants Party, in 1988.[63] The show was purchased in 60,000 homes and grossed $1.2 million.[69] In 1989, following an on-air challenge between Stern and his producer Gary Dell'Abate, fans packed out Nassau Coliseum for Howard Stern's U.S. Open Sores, a live event that featured a tennis match between Stern and Dell'Abate.[63] Stern released both events for home video which sold tens of thousands.

In 1990, Rolling Stone predicted Stern was set "on the fast track to multimedia stardom".[32] He re-signed with Infinity to continue his radio show for another five years, a deal that New York Magazine estimated was worth over $10 million.[61] In the same year, Stern began to host a weekly late-night variety show titled The Howard Stern Show on WWOR-TV featuring himself and his radio show staff. Following its debut in July 1990, the show was syndicated to a peak of 65 television markets nationwide.[70] In the New York area, the show frequently managed to overtake Saturday Night Live in the ratings during the half an hour the two shows overlapped. The series ended in 1992 after 69 episodes. In light of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issuing its first fine to Infinity over material it deemed indecent, Stern released a compilation album of censored moments from his radio show on cassette and CD as Crucified by the FCC in February 1991.[71]

In 1992, Stern's increasing popularity as a radio and television personality led to him describing himself as "King of All Media".[72] In October that year, Stern became the first to have the number one morning radio show in New York and Los Angeles simultaneously.[73] In the same month Stern released Butt Bongo Fiesta, his third home video containing the highlight feature of "butt bongoing", an act Stern described as "frenetic spanking in time to a rock record playing in the background".[74] The video was a commercial success; approximately 260,000 copies were sold for a gross of over $10 million.[71][75] In November 1992, Stern returned to Saturday night television as the host of The Howard Stern "Interview", a one-on-one celebrity interview series on the E! network which ended in 1993.[72]

Stern appeared at the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards as Fartman, a fictional superhero originating from the humor magazine National Lampoon. According to the trademark Stern filed for the character in October 1992, he first used Fartman at WWDC in July 1981.[76] Development for The Adventures of Fartman, a feature film based around the character, began in late 1992 with Stern reaching a verbal agreement with New Line Cinema to release it.[77] Screenwriter J. F. Lawton was hired to prepare an outline to a script and to direct the film with producer David Permut which received a budget of $8–11 million. Lawton described the film as "a real comedy with a beginning, middle and an end with a strong story".[78] In 1993, the project was abandoned due to disagreements between Stern and New Line regarding the film's content, rating, and merchandising rights.[79][80]

1993–94: Private Parts, E! show, and run for Governor of New York

In early 1993, Stern signed a $1 million contract with publisher Simon & Schuster to write his first book, Private Parts .[81] The book was co-authored by Larry Sloman and edited by Judith Regan. Stern described his time writing the book as "the most challenging thing I have ever done in my career".[82] Upon its release on October 7, 1993, Private Parts was an immediate success. The entire first print of 225,000 copies were sold within hours of going on sale. In five days, it became the fastest-selling title in the history of Simon & Schuster.[83] Over one million copies were distributed after two weeks.[75][81] Private Parts entered the The New York Times Best-Seller list at number one and stayed on the list for 20 weeks in total.[84] Stern's book signing tour was attended by thousands; the first in New York City was attended by an estimated 10,000 people.[81] The success of Private Parts led to Stern being offered various business deals, including his first of three cover stories for Rolling Stone.[85] He stated, "I began getting calls from every film executive and television type. Suddenly, I was a mainstream performer who had real clout in the marketplace—I was bankable. Immediately they would forget about my most controversial material and the fact that I could be real dangerous as a broadcaster."[86]

Stern hosted his second pay-per-view event, The Miss Howard Stern New Year's Eve Pageant, on December 31, 1993. The show was based around a mock beauty pageant with celebrity judges to crown the first "Miss Howard Stern". It broke the subscriber record for a non-sports event which was previously held by a New Kids on the Block concert in 1990.[75] An estimated 40,000 households purchased the show for a gross of $16 million.[87] The show was released for home video entitled Howard Stern's New Year's Rotten Eve 1994. Between his book royalties and pay-per-view profits, Stern's earnings in the latter months of 1993 were an estimated $7.5 million.[88] In its 20th anniversary issue issued in 1993, Radio & Records named Stern "the most influential air personality of the past two decades".[89]

In June 1994, Stern founded the Howard Stern Production Company for "original film and television production enterprises as well as joint production and development ventures". He intended to assist in a feature film adaptation of Brother Sam, the biography of comedian Sam Kinison.[90]

In 1994, Billboard added the "Nationally Syndicated Air Personality of the Year" category to its annual radio awards that is based on "entertainment value, creativity, and ratings success".[91] Stern was awarded the title every year from 1994 to 2002.[92][93] In the New York market, The Howard Stern Show was the highest-rated morning program for seven consecutive years between 1994 and 2001.[94]

During his radio show on March 21, 1994, Stern announced his candidacy for Governor of New York under the Libertarian Party ticket, challenging Mario Cuomo for re-election.[95] Stern planned to reinstate the death penalty, stagger highway tolls to improve traffic flow, and limit road work to night hours.[96] At the party's nomination convention on April 23, 1994, Stern won the required two-thirds majority on the first ballot, receiving 287 of the 381 votes cast (75.33%). James Ostrowski finished second with 34 votes (8.92%).[97] To place his name on the November ballot, Stern was obliged to state his home address and to complete a financial disclosure form under the Ethics in Government Act of 1987. After declining to disclose his financial information, Stern was denied an injunction on August 2, 1994.[98] He withdrew his candidacy two days later. Cuomo was defeated in the gubernatorial election on November 8, 1994, by George Pataki, whom Stern backed. Pataki signed The Howard Stern Bill that limited construction on state roads to night hours in New York City and Long Island, in 1995.

In June 1994, Stern's radio show began to be filmed for a half-hour television show on E!.[99] Howard Stern ran for eleven years until the last taped episode aired on July 8, 2005.[100] In conjunction with his move to satellite radio, Stern launched Howard Stern on Demand, a subscription video-on-demand service, on November 18.[101] The service relaunched as Howard TV on March 16, 2006.[102]

1995–97: Miss America and Private Parts film

On April 3, 1995, three days after the shooting of singer Selena, Stern's comments regarding her death and Mexican Americans caused an uproar in the Hispanic community. He criticized her music and gunfire sound effects were played over her songs. "This music does absolutely nothing for me. Alvin and the Chipmunks have more soul ... Spanish people have the worst taste in music. They have no depth".[103] On April 6, Stern responded with a statement in Spanish, stressing his comments were made in satire and not intended to hurt those who loved her.[104] A day later, Justice of the Peace Eloy Cano of Harlingen, Texas, issued an arrest warrant on Stern for disorderly conduct,[105] but Stern was never arrested.[106]

Stern signed a deal with ReganBooks worth $3 million in 1995 to write his second book, Miss America.[107] He writes about his cybersex experiences on the Prodigy service, a private meeting with Michael Jackson, and his experiences with back pain and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[108] Miss America was released on November 7, 1995. On the day, Barnes & Noble sold 33,000 copies which set a new one-day record.[109] It entered The New York Times Best-Seller list at number one and stayed on the list for 16 weeks.[84] The book broke the previous record for the fastest selling book in one day, previously being Sex by Madonna in 1992. Publishers Weekly reported 1.39 million copies were sold by the end of the year and ranked Miss America the third best-selling book of 1995.[110]

In 1996, production on a biographical comedy film adaptation of Private Parts began. Stern said, "Two years before Ivan Reitman got involved ... It started to look as if the film wasn't going to be made because I had final script approval and I rejected every script there was ... they were over the top comedies that I think were dumb, boring and dull."[111] Filming began in May 1996 and lasted for four months with Stern and his radio show staff playing themselves.[112] Stern embarked on an extensive publicity tour to promote the film. Private Parts opened at The Theatre at Madison Square Garden on February 27, 1997, where Stern performed "The Great American Nightmare" with Rob Zombie.[113] The film's wide release followed on March 7, 1997. It topped the US box office in its opening weekend with a gross of $14.6 million. It went on to earn a total of $41.2 million domestically.[114] In 1998, Stern received a Blockbuster Entertainment Award for "Favorite Male Newcomer" and was nominated for a Golden Satellite Award for "Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture (Comedy)" and a Golden Raspberry Award for "Worst New Star".[citation needed] The film's soundtrack sold 178,000 copies in its first week of release and reached number one on the Billboard 200 chart for one week.[115] Stern performs on "The Great American Nightmare" and "Tortured Man", a song co-written with The Dust Brothers.

In October 1997, Stern filed a $1.5 million lawsuit against Ministry of Film Inc., claiming the studio recruited him for a film called Jane starring Melanie Griffith while knowing it had insufficient funds. Stern, who remained unpaid when production ceased, accused the studio of breach of contract, fraud, and negligent representation.[116] A settlement was reached in 1999 which resulted in Stern receiving $50,000.[117]

1998–2004: CBS show and television and film productions

In August 1998, Stern returned to Saturday night television with The Howard Stern Radio Show,[118] an hour-long program broadcast nationwide on CBS affiliates featuring radio show highlights with material unseen in his nightly E! show. The show competed for ratings alongside Saturday Night Live on NBC and MADtv on Fox. Concerned with its risqué content, affiliates began to leave the show after two episodes.[119] Making its launch on 79 stations on August 22, 1998, this number was reduced to 55 by June 1999.[120] A total of 84 episodes were broadcast.[citation needed] The final re-run aired on November 17, 2001, to around 30 markets.[121][122]

In 1998, Stern wrote forewords for Steal This Dream, a biography of Abbie Hoffman written by Sloman, and Disgustingly Dirty Joke Book by Jackie Martling.

In September 1999, UPN announced the production of Doomsday, an animated science-fiction comedy series executively produced by Stern.[123] Originally set for a 2000 release, Stern starred as Orinthal, a family dog.[124] The project was eventually abandoned. From 2000 to 2002, Stern was the executive producer of Son of the Beach, a sitcom which ran for three seasons on FX. In late 2001, Howard Stern Productions was reportedly developing a new sitcom titled Kane.[125] The pilot episode was never filmed.

In 2002, Stern acquired the rights to the comedy films Rock 'n' Roll High School (1979) and Porky's (1982) with Arclight Films. He expressed a wish to use a remake of the former as a launchpad for an unknown band. Under the deal, Stern was served as executive producer and was allowed to place "Howard Stern Presents" in the titles. He reasoned, "If I say to ... my audience, this is 'Howard Stern Presents,' it means something to them ... it's going to be crazy. It means that it's going to be different, and they know I'm not going to be giving them any schlock."[126] Development for Porky's was halted in 2011 following legal action regarding the ownership of the film's rights.[127]

In early 2004, Stern spoke of talks with ABC to host a primetime television interview program, but the project never materialized. In August 2004, cable channel Spike picked up 13 episodes of Howard Stern: The High School Years, an animated series Stern was to executive produce.[128] On November 14, 2005, Stern announced the completion of episode scripts and 30 seconds of test animations.[129] Stern eventually gave the project up. In 2007 he explained the episodes could have been produced "on the cheap" at $300,000 each, though the quality he demanded would have cost over $1 million.[130] Actor Michael Cera was cast as the lead voice.[131]

2004–10: Signing with Sirius and terrestrial radio departure

On October 6, 2004 Stern signed a five-year contract with Sirius Satellite Radio, a medium free from FCC regulations, starting in January 2006.[132] His decision to leave terrestrial radio occurred in the aftermath of the controversial Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show in February 2004, where Stern became a target in the U.S. government's crackdown on indecency in broadcasting. The incident prompted tighter control over content by station owners and managers which left Stern feeling creatively "dead inside".[133] Stern hosted his final broadcast on WXRK on December 16, 2005.[134] A stage was constructed outside the radio station where Stern and his radio show staff made their farewell speeches. During his 20 years at WXRK his show had syndicated in 60 markets[135][136] across the U.S. and Canada and gained a peak audience of 20 million listeners.[137][138][139]

With an annual budget of $100 million for all production, staff and programming costs, Stern launched two channels on Sirius in 2005 named Howard 100 and Howard 101. He assembled the Howard 100 News team that covered stories about his show and those associated with it. A new studio was constructed at Sirius' headquarters in New York dedicated specifically for the shows.[140] On January 9, 2006, the day of his first broadcast, Stern and his agent received 34.3 million shares of stock from the company worth $218 million for exceeding subscriber targets set in 2004.[141] A second stock incentive was paid in 2007, with Stern receiving 22 million shares worth $82.9 million.[142] In the same month, Time magazine included Stern in its Time 100 list.[143] He also ranked seventh in Forbes' Celebrity 100 list in June 2006.[144]

On February 28, 2006, CBS Radio (formerly Infinity Broadcasting) filed a lawsuit against Stern, his agent, and Sirius, claiming that Stern misused CBS broadcast time to promote Sirius for unjust enrichment during his last 14 months on terrestrial radio.[145][146] In a press conference held hours before the suit was filed, Stern said it was nothing more than a "personal vendetta" against him by CBS president Leslie Moonves.[147] A settlement was reached on May 25, with Sirius paying $2 million to CBS for control of Stern's 20-year broadcast archives.[148]

2010–present: Sirius contract renewal and America's Got Talent

In December 2010, Stern re-signed his contract with Sirius to continue his show for a further five years.[149] The new contract allowed Stern to work a reduced schedule from four to three-day working weeks.[150] Following the agreement, Stern and his agent filed a lawsuit against Sirius on March 22, 2011, for allegedly failing to pay the stock bonuses promised to them from the past four years while helping the company exceed subscriber growth targets. Sirius said it was "surprised and disappointed" by the suit.[151] On April 17, 2012, Judge Barbara Kapnick dismissed the lawsuit and prevented Stern and his agent from filing lawsuits for similar allegations.[152]

In 2011,[153] Stern replaced Piers Morgan as a judge on America's Got Talent for its seventh season.[154][155] The move made him reappear on Forbes' Celebrity 100 list at number 26.[156] He continued as a judge for the eighth[157] and its most recent ninth season.

Though critical of the organization, Stern was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2012.[2] In August 2013, Stern and Simon Cowell shared first place on Forbes' list of America's highest-paid television personalities with $95 million earned between June 2012–13.[158] Stern and Cowell tied first place in the following year's poll with the same amount earned from June 2013–14.[159]

On January 31, 2014, a Howard Stern Birthday Bash event was held at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City in celebration of Stern's 60th birthday. The four-hour show aired for free on SiriusXM.[160]

FCC fines

Between 1990 and 2004, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) fined owners of radio station licensees that carried The Howard Stern Show a total of $2.5 million for content it considered to be indecent.[161]

Personal life

Stern met his first wife, Alison Berns,[162] when he was at Boston University. Stern wrote, "Within a week after our relationship began, I knew I was going to marry her."[163] They married at Temple Ohabei Shalom in Brookline, Massachusetts on June 4, 1978.[164] They have three daughters: Emily Beth (b. 1983), Debra Jennifer (b. 1986), and Ashley Jade (b. 1993).[165] In October 1999, they decided to separate[166] and Stern moved into his apartment in the Upper West Side of Manhattan which he bought in 1998.[167] Stern said, "I was totally neurotic and sort of consumed with work. I took work as the most important thing and the only thing."[168] The marriage ended in 2001 with an amicable divorce and settlement.[162]

In 2000, Stern began dating model and television host Beth Ostrosky.[169] Their engagement was announced on February 14, 2007.[162] They married at Le Cirque restaurant in New York City that was officiated by Mark Consuelos on October 3, 2008.[170]

Stern was taught how to play chess when he was growing up on Long Island. He has played on the Internet Chess Club and has taken online lessons from the website's founder, chess master Dan Heisman. Stern has achieved a rating of over 1600.[171]

In the early 1970s, Stern's parents began to practice Transcendental Meditation and encouraged him to learn the technique. Stern credits it with helping him to quit smoking, achieve his goals in radio, and curing his mother of depression.[172] He continues to practice it to this day.[173]

As part of the radio show's Staff Revelations Game in January 2006, Stern revealed he underwent rhinoplasty and had liposuction under his chin in the 1990s.[174]

In 2011, Stern took up photography and shot layouts for Hamptons that July.[175][176] He has also shot for WHIRL and the North Shore Animal League.[177][178]

In May 2013, Stern bought a home in Palm Beach, Florida, for a reported $52 million that covers 19,000 square feet.[179][180]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Ryder, P.I. | Ben Wah | |

| 1988 | Howard Stern's Negligeé and Underpants Party | Himself | Host |

| 1989 | Howard Stern's U.S. Open Sores | Himself | Host |

| 1992 | Butt Bongo Fiesta | Himself | Host |

| 1994 | Howard Stern's New Year's Rotten Eve 1994 | Himself | Host |

| 1997 | Private Parts | Himself | Blockbuster Entertainment Award for "Favourite Male Newcomer" (1998)[citation needed] Nominated – Golden Raspberry Award for "Worst New Star" (1998)[citation needed] Nominated – Golden Satellite Award for "Best Male Actor Performance in a Comedy or Musical" (1998)[citation needed] |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | The Howard Stern Show | Himself | Host Never aired |

| 1990–1992 | The Howard Stern Show | Himself | Host |

| 1992–1993 | The Howard Stern "Interview" | Himself | Host |

| 1994–2005 | Howard Stern | Himself | Host |

| 1998–2001 | The Howard Stern Radio Show | Himself | Host |

| 2005–2013 | Howard TV | Himself | Host |

| 2012– present | America's Got Talent | Himself | Judge |

Discography

| Year | Album | Label | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 50 Ways to Rank Your Mother | Wren Records | Re-released as Unclean Beaver (1994) on Ichiban/Citizen X labels |

| 1991 | Crucified By the FCC | Infinity Broadcasting | |

| 1997 | Private Parts: The Album | Warner Bros. | Billboard 200 Number-one album from March 15–21, 1997 |

Bibliography

- Stern, Howard (1993). Private Parts. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-88016-3.

- Stern, Howard (1995). Miss America. ReganBooks. ISBN 978-0-06-039167-6.

References

- ^ "NewsMax Top 25 Radio Hosts". Newsmax. November 29, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ a b Feder, Robert (June 28, 2012). "Howard Stern comments on Radio Hall of Fame". Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Colford, p. 2.

- ^ "Howard Stern". jewornotjew.com. January 17, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "The Hollowverse - The religions and political views of Howard Stern". Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Reitwiesner, William. "Ancestry of Howard Stern". WARGS.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; January 22, 2012 suggested (help) - ^ Stern 1993, p. 44.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 92.

- ^ a b Colford, p. 7.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 46.

- ^ Colford, p. 3.

- ^ a b Colford, p. 9.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 111.

- ^ Pietroluongo, Silvio; Trust, Gary (January 20, 2014). "Howard Stern: The Billboard Cover Q&A". Billboard. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "CNN Larry King Live - Interview With Howard Stern". CNN Transcripts. January 5, 2006. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 113.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 114.

- ^ a b Stern 1993, p. 65.

- ^ a b c "The History of Howard Stern Act I Interactive Guide". Sirius Satellite Radio. December 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2010.

- ^ Ketcham, Diane (February 12, 1995). "At the Repository of High School Memories". New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c Stern 1993, p. 115.

- ^ Stern 1993, pp. 115–117.

- ^ Colford, p. 31.

- ^ a b Stern 1993, p. 121.

- ^ Zitz, Michael (July 1, 1994). "Stern's Start". The Free Lance-Star. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Stern 1993, p. 123.

- ^ Kaplan, Jason. "Howard Confronts FCC Chairman Michael Powell!". howardstern.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013.

7. Howard Stern's Italian name is "Tzvi." (True)

- ^ "Boston University 2009-10 College of Communication Bulletin". Boston University. Archived from the original on May 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c Stern 1993, p. 118.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 119.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Wild, David (March 16, 2011). "Who Is Howard Stern? Rolling Stone's 1990 Feature". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 125.

- ^ Colford, p. 45.

- ^ Stern 1993, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Luerssen, p. 157.

- ^ Colford, p. 48.

- ^ Colford, p. 74.

- ^ Colford, p.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Colford, p. 52.

- ^ Colford, p. 57.

- ^ Colford, p. 61.

- ^ a b Stern 1993, p. 134.

- ^ Craig, Jeff (September 4, 1997). "Stern warning". Jam!. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Billboard's Radio Winners Named". Billboard. August 1, 1981. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ Colford, p. 62.

- ^ Colford, p. 67.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 135.

- ^ Colford, p. 63.

- ^ Colford, p. 68

- ^ Stern 1993, pp. 138–140.

- ^ Colford, p. 78.

- ^ Colford, p. 81.

- ^ Colford, p. 85.

- ^ Colford, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Colford, p. 89.

- ^ Colford, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Colford, pp. 91–93.

- ^ "WNBC's Stern Is Rendered Speechless". Billboard. September 11, 1982. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Kasindorf, Jeanie (November 23, 1992). "Bad Mouth. Howard Stern vs The FCC". New York Magazine. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ Colford, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d e "The History of Howard Stern Act II Interactive Guide". Sirius Satellite Radio. December 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ^ Luerssen, p. 12.

- ^ Stern 1993, p. 185.

- ^ Colford, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Colford, p. 181.

- ^ Kubasik, Ben (August 12, 1987). "TV Spots". Newsday. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ Colford, p. 186.

- ^ Colford, pp. 197–201.

- ^ a b "The History of Howard Stern Act III On-Air Schedule". Sirius Satellite Radio. December 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Tucker, Ken (January 22, 1993). "The Howard Stern Interview (1992-1993)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (October 7, 1992). "Howard Stern Talks His Way to No. 1 Status Radio". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Stern 1997, p. 441.

- ^ a b c Mills, Joshua (October 24, 1993). "He Keeps Giving New Meaning To Gross Revenue". New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ "Fartman Trademark". United States Patent and Trademark Office. October 16, 1992. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ Colford, p. 202.

- ^ Lawton directs Stern in wind-breaking film variety.com, November 25, 1992</ref On June 28, 1993, Time

- ^ Brennan, Judy (January 30, 1994). "Stern's New Year's Party Fallout 'The Miss Howard Stern Pageant' was a pay-TV bonanza but may have cost him a movie career". Los Angeles Time. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Schaefer, Stephen (May 7, 1993). "Running Out of Gas". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Colford, pp. 222–223. Cite error: The named reference "col222" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Luerssen, p. 94.

- ^ "Stern's Private Parts Tops Limbaugh's Mark". The Wichita Eagle. October 20, 1993. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

"Five days after its publication, Private Parts, had become the fastest-selling book in the 70-year history of Simon & Schuster".

- ^ a b Carter, Bill (October 11, 2004). "Where Some See Just a Shock Jock, Sirius Sees a Top Pitchman". New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ Marin, Rick (March 16, 2011). "Howard Stern: Man or Mouth? Rolling Stone's 1994 Cover Story". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Stern 1996, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Svetkey, Benjamin (January 21, 1994). "Stern Spurned". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Colford, p. 226.

- ^ Colford, p. 254.

- ^ "Entertainment News". Star-Banner. June 24, 1994. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ "Honoring Best In Broadcasting". Billboard. October 21, 2000. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ Graybow, Steven (March 30, 2002). "WLTW, KKBT, KROQ, WQYK Lead Billboard Radio Awards". Billboard. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ Graybow, Steven (February 22, 2003). "Radio Awards Dial Up First-Time Winners". Billboard. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ Hinkley, David (April 23, 2001). "Hot-97 Returns To The Top". Daily News. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ Colford, p. 232.

- ^ Gillespie, Nick (July 1994). "Stern Message". Reason. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Our Campaigns (April 23, 1994). "LBT Convention Race - April 23, 1994". Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Colford, p. 243.

- ^ "Howard Stern to Star, Condensed, on TV". New York Times. 1 June 1994. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Martin, Denise (June 21, 2005). "Stern cancels E! ticket". Variety. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Huff, Richard (November 17, 2005). "'On Demand' Will Bare More Of Stern Footage". Daily News. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Wolk, Josh (31 March 2005). "Hangin' With Howard". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Asin, Stephanie (April 6, 1995). "Selena's Public Outraged: Shock Jock Howard Stern's Comments Hit Raw Nerve". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 10, 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ^ "Satire triggers a Stern outcry, puts 'shock jock' on defensive". The Deseret News. April 6, 1995. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Hinckley, David (April 13, 1995). "Judge Wants Stern To Face Music For Selena Comments". Daily News. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ "Stern's Most Shocking Moments!". TMZ. December 15, 2005. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ Colford, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Jacobs, A. J. (December 1, 1995). "Miss America (1996)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Tabor, Mary (November 15, 1995). "Stern Guns Down Powell Book". New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ Lucaire, p. 145.

- ^ Luerssen, p. 92.

- ^ Colford, p. 268.

- ^ Millner, Denene (February 27, 1997). "'Private Parts' a Public Hassle". Daily News. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "Private Parts". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ^ "Stern Talks About Chart-Topping Soundtrack". MTV News. March 7, 1997. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "Stern sues movie studio, says it reneged on deal". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. 10 October 1997. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "Studio avoids court by giving Stern $50,000". Saratosa Herald-Tribune. August 25, 1999. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Sakamoto, John (April 1, 1998). "Stern's TV show to debut in August". Jam! Showbiz. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Mink, Eric (September 2, 1998). "Texas TV Station Boots 'Stern'". Daily News. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Luerssen, p. 148.

- ^ Petrozzello, Donna (November 15, 2001). "Stern Going Off The Air". Daily News. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ "Howard Stern's Radio Show Leaving TV". Media Post News. November 16, 2001. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ "Stern's 'Doomsday' dawns at UPN". Reading Eagle. September 17, 1999. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ "UPN Show Enlists Stern As An Animated Talker". Daily News. September 16, 1999. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ Schneider, Michael (November 16, 2001). "Stern, CBS part for sitcom". Reuters. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ "Howard Stern To Remake 'Rock'N'Roll' High School". Billboard. November 1, 2002. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (March 28, 2011). "Will a Legal Fight Ensnare Howard Stern's Planned 'Porky's' Remake? (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "DJ Stern to star in own cartoon". BBC News. August 22, 2004. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Kaplan, Jason (November 14, 2005). "Howard Gets Animated". howardstern.com. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Kaplan, Jason (September 10, 2007). "Very Dark For A Cartoon". howardstern.com. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Kaplan, Jason (January 5, 2010). "Today's Show Companion". howardstern.com. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Kaplan, Jason (October 6, 2004). "Howard To Sirius Satellite In '06 - Predicts End Of Broadcast Radio!". howardstern.com. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (December 11, 2005). "Stern On Satellite: A Bruised Flower, Blossoming Anew". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ Kaplan, Jason (December 16, 2005). "The Last Rundown (On FM)". howardstern.com. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Deggans, Eric (December 11, 2005). "Bubba, Relaunched". St. Petersburg Times.

- ^ Tucker, Ken (March 3, 2006). "Communication Sharpens Syndie Sword". Billboard Radio Monitor.

- ^ Condran, Ed (July 31, 1998). "Stern Producer Flourishes By The Skin Of His Teeth". The Morning Call.

- ^ James, Renee (October 1, 2006). "Hmmm? Stern's critics are plugged into regular radio". The Morning Call.

- ^ Sullivan, James (December 14, 2005). "Love him or hate him, Stern is a true pioneer". MSNBC.

- ^ "Sirius Satellite Radio Inc. 8-K For 10/1/04". SEC Info. October 1, 2004. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "Howard Stern & Co. Score $200M Payout". CNN Money. January 5, 2006. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- ^ "Howard Stern wins $83M bonus from Sirius". CBC News. January 9, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ Spade, David (May 2006). "Howard Stern New King Of Satellite". Time. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ "Top 100 Most Powerful Celebrities - Howard Stern". Forbes. June 2006. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ "CBS Radio files lawsuit against Stern, Sirius". CBS News. March 1, 2006. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ "CBS Radio Files Lawsuit Against Howard Stern". FMQB. February 28, 2006. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (March 1, 2006). "Radio star Howard Stern in 'Sirius' legal trouble". MSNBC. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ "Stern Gets Old Tapes, CBS Gets $2M". CBS News. May 25, 2006. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ Huff, Richard (December 9, 2010). "Howard Stern to stay with Sirius Satellite Radio; signs new five-year contract". Daily News. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Harp, Justin (May 3, 2011). "Howard Stern begins reduced Sirius XM schedule". Digital Spy Limited. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ^ "Stern sues Sirius over bonus pay for subscribers". ABC News. March 22, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ "Howard Stern's $300 Million Lawsuit Bounced". The Smoking Gun. April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (December 15, 2011). "Howard Stern To Judge On 'America's Got Talent'". MTV. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Villarreal, Yvonne. "Howard Stern returning to 'America's Got Talent'". latimes.com. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Kuperinsky, Amy. "America's Got Talent: Top 48 begin performances at NJPAC", The Star-Ledger, July 3, 2012

- ^ "The World's Most Powerful Celebrities". Forbes. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ Yahr, Emily (April 3, 2013). "'America's Got Talent' moving once again, this time to Radio City Music Hall". Washington Post. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Parr, Hayley (August 9, 2013). "Simon Cowell and Howard Stern top Forbes' list of highest-paid TV personalities". The Independent. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Pomerantz, Dorothy (November 3, 2014). "Simon Cowell And Howard Stern Are Entertainment's Top-Earning Personalities". Forbes. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Trust, Gary (February 1, 2014). "Howard Stern's 60th Bash: The Full Report From The Birthday Blowout". Billboard. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Dunbar, John (April 9, 2004). "Indecency on the Air. Shock-radio jock Howard Stern remains 'King of All Fines'". The Center for Public Integrity. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Howard Stern Engaged To Model Girlfriend", Associated Press via The Washington Post, February 14, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Rich (March 16, 2011). "Howard Stern Does Hollywood: Rolling Stone's 1997 Cover Story". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Hoffman, Matthew. The Completely Unauthorized Howard Stern (Courage Books, 1998), ISBN 978-0-7624-0377-6, p. 25

- ^ Phillips, Erica (February 21, 2006). "Meet: The Cast". Sirius Satellite Radio. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ Hinkley, David (February 8, 2000). "Stern's Dating Rating Game". Daily News. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Errico, Marcus (October 23, 1999). "Howard Stern, Wife Separate". E! Online. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (March 31, 2011). "Howard Stern's Long Struggle and Neurotic Triumph". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Chris Harris and Sarah Muller (October 14, 2008). "Howard Stern's Wife, Beth Ostrosky, Talks About Recent Wedding". MTV.

- ^ Calabrese, Erin (October 3, 2008). "Howard Stern Gets Married". The New York Post. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ Loeb McClain, Dylan (October 18, 2008). "Long a Player, Howard Stern Gets Serious About His Game". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ Mwangaguhunga, Ron (February 21, 2006). "Howard Stern And Transcendental Meditation". Awarenessblog. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ Colford, p. 29.

- ^ "Howard Stern (Before) | Celebrity Plastic Surgery | Comcast.net". Xfinity.comcast.net. February 22, 2009. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ "Howard Stern Swaps Photography For Chess". July 13, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Katie. "The Stunning Beth Ostrosky Stern". Hamptons. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Tumpson, Christine (October 4, 2011). "Perfect Ten". WHIRL Magazine. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ "2012 Animal League Calendar Featuring Beth Stern". North Shore Animal League. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Battaglio, Stephen; Schneider, Michael; Wagmeister, Elizabeth (August 26, 2013). "What They Earn". TV Guide. pp. 16 - 20.

- ^ Hofheinz, Darrell (May 15, 2013). "Meet the new neighbor: Howard Stern reportedly pays $52 million for Palm Beach home". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

Sources

- Stern, Howard; Larry Sloman (1996). Judith Regan (ed.). Miss America (Paperback ed.). ReganBooks. ISBN 978-0-06-109550-4.

- Stern, Howard (1993). Private Parts (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-88016-3.

- Colford, Paul (1997). Howard Stern: King of All Media (2nd ed.). St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-96221-0.

- Lucaire, Luigi (1997). Howard Stern, A to Z: A Totally Unauthorized Guide. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-15144-7.

- Luerssen, John (2009). American Icon: The Howard Stern Reader. Lulu. ISBN 978-0-557-04204-3.

External links

- Howard Stern

- 1954 births

- Living people

- American actor-politicians

- American autobiographers

- American male comedians

- America's Got Talent

- American people of Austrian-Jewish descent

- American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent

- American talk radio hosts

- American television personalities

- American television talk show hosts

- Boston University College of Communications alumni

- Critics of religions

- Free speech activists

- Jewish American male actors

- Jewish American writers

- Jewish male comedians

- Male actors from New York City

- National Radio Hall of Fame inductees

- Obscenity controversies

- People from Jackson Heights, Queens

- People from Rockville Centre, New York

- Photographers from New York

- Radio personalities from New York City

- Reality television judges

- Religious skeptics

- Shock jocks

- Sirius Satellite Radio

- Television producers from New York

- Transcendental Meditation practitioners

- Writers from New York City

- Critics of feminism