Jim Brown

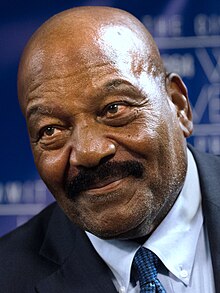

Brown in 2014 | |||||||||||||||

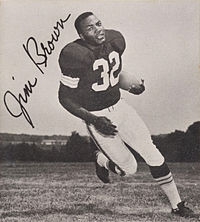

| No. 32 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position: | Fullback | ||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||

| Born: | February 17, 1936 St. Simons Island, Georgia, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Height: | 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) | ||||||||||||||

| Weight: | 232 lb (105 kg) | ||||||||||||||

| Career information | |||||||||||||||

| High school: | Manhasset (Manhasset, New York) | ||||||||||||||

| College: | Syracuse (1954–1956) | ||||||||||||||

| NFL draft: | 1957 / round: 1 / pick: 6 | ||||||||||||||

| Career history | |||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Career NFL statistics | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

James Nathaniel Brown (born February 17, 1936) is an American former football player, sports analyst and actor. He played as a fullback for the Cleveland Browns of the National Football League (NFL) from 1957 through 1965. Considered to be one of the greatest running backs of all time, as well as one of the greatest players in NFL history,[1] Brown was a Pro Bowl invitee every season he was in the league, was recognized as the AP NFL Most Valuable Player three times, and won an NFL championship with the Browns in 1964. He led the league in rushing yards in eight out of his nine seasons, and by the time he retired, he held most major rushing records. In 2002, he was named by The Sporting News as the greatest professional football player ever.[2]

Brown earned unanimous All-America honors playing college football at Syracuse University, where he was an all-around player for the Syracuse Orangemen football team. The team later retired his number 44 jersey, and he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1995. He also excelled in basketball, track and field, and lacrosse. He is also widely considered one of the greatest lacrosse players of all time,[3][4][5] and the Premier Lacrosse League MVP Award is named in his honor.[6]

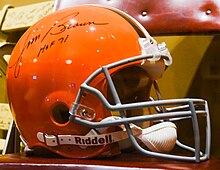

In his professional career, Brown carried the ball 2,359 times for 12,312 rushing yards and 106 touchdowns, which were all records when he retired. He averaged 104.3 rushing yards per game, and is the only player in NFL history to average over 100 rushing yards per game for his career. His 5.2 yards per rush is third-best among running backs, behind Marion Motley and Jamaal Charles.[7] Brown was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1971. He was named to the NFL's 50th, 75th, and 100th Anniversary All-Time Teams, comprising the best players in NFL history. Brown was honored at the 2020 College Football Playoff National Championship as the greatest college football player of all time.[8][9] His number 32 jersey is retired by the Browns. Shortly before the end of his football career, Brown became an actor, and had several leading roles throughout the 1970s.

Early life

Brown was born in St. Simons Island, Georgia, to Swinton Brown, a professional boxer, and his wife, Theresa, a homemaker.[10]

At Manhasset Secondary School, Brown earned 13 letters playing football, lacrosse, baseball, basketball, and running track.[11]

Mr. Brown credits his self-reliance to having grown up on Saint Simons Island, a community off the coast of Georgia where he was raised by his grandmother and where racism did not affect him directly. At the age of eight, he moved to Manhasset, New York, on Long Island, where his mother worked as a domestic. It was at Manhasset High School that he became a football star and athletic legend.

— The New York Times – film review, 2002.[11]

He averaged a then-Long Island record 38 points per game for his basketball team. That record was later broken by future Boston Red Sox star Carl Yastrzemski of Bridgehampton.[12]

College career

As a sophomore at Syracuse University (1954), Brown was the second-leading rusher on the team. As a junior, he rushed for 676 yards (5.2 per carry). In his senior year in 1956, Brown was a consensus first-team All-American. He finished fifth in the Heisman Trophy voting and set school records for highest season rush average (6.2) and most rushing touchdowns in a single game (6). He ran for 986 yards—third-most in the country despite Syracuse playing only eight games—and scored 14 touchdowns. In the regular-season finale, a 61–7 rout of Colgate, he rushed for 197 yards, scored six touchdowns, and kicked seven extra points for a school-record 43 points. Then in the Cotton Bowl, he rushed for 132 yards, scored three touchdowns, and kicked three extra points, but a blocked extra point after Syracuse's third touchdown was the difference as TCU won 28–27.[13]

Perhaps more impressive was his success as a multisport athlete. In addition to his football accomplishments, he excelled in basketball, track, and especially lacrosse. As a sophomore, he was the second-leading scorer for the basketball team (15 ppg), and earned a letter on the track team. In 1955, he finished in fifth place in the National Championship decathlon.[14] His junior year, he averaged 11.3 points in basketball, and was named a second-team All-American in lacrosse. His senior year, he was named a first-team All-American in lacrosse (43 goals in 10 games to rank second in scoring nationally). Brown was so dominant in the game, that lacrosse rules were changed requiring a lacrosse player to keep their stick in constant motion when carrying the ball (instead of holding it close to his body).[15][16] There is currently no rule in lacrosse that requires a player to keep his stick in motion. He is in the Lacrosse Hall of Fame.[17] The JMA Wireless Dome has an 800 square-foot tapestry depicting Brown in football and lacrosse uniforms with the words "Greatest Player Ever".[18]

While in college, Brown participated in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps.[19] After graduating he was commissioned as a second lieutenant.[19] During his time in the NFL, Brown continued his military commitment as a member of the United States Army Reserve.[19] He served for four years and was discharged with the rank of captain.[19]

Professional career

Brown was taken in the first round of the 1957 NFL draft by the Cleveland Browns, the sixth overall selection.[20] In the ninth game of his rookie season, against the Los Angeles Rams he rushed for 237 yards,[21] setting an NFL single-game record that stood unsurpassed for 14 years[a] and a rookie record that remained for 40 years.

Brown broke the single-season rushing record in 1958, gaining 1,527 yards in the 12-game season, shattering the previous NFL mark of 1,146 yards set by Steve Van Buren in 1949.[23] In this MVP season, Brown led all players with a staggering 17 touchdowns scored, beating his nearest rival, Baltimore Colts wide receiver Raymond Berry, by 8.[23]

After nine years in the NFL, he departed as the league's record holder for both single-season (1,863 in 1963) and career rushing (12,312 yards), as well as the all-time leader in rushing touchdowns (106), total touchdowns (126), and all-purpose yards (15,549). He was the first player to reach the 100-rushing-touchdowns milestone, and only a few others have done so since, despite the league's expansion to a 16-game season in 1978 (Brown's first four seasons were only 12 games, and his last five were 14 games).

Brown's record of scoring 100 touchdowns in only 93 games stood until LaDainian Tomlinson did it in 89 games during the 2006 season. Brown holds the record for total seasons leading the NFL in all-purpose yards (five: 1958–1961, 1964), and is the only rusher in NFL history to average over 100 yards per game for a career. In addition to his rushing, Brown was a superb receiver out of the backfield, catching 262 passes for 2,499 yards and 20 touchdowns, while also adding another 628 yards returning kickoffs.

Every season he played, Brown was voted into the Pro Bowl, and he left the league in style by scoring three touchdowns in his final Pro Bowl game. He accomplished these records despite not playing past 29 years of age. Brown's six games with at least four touchdowns remains an NFL record. Tomlinson and Marshall Faulk both have five games with four touchdowns.

Brown led the league in rushing a record eight times. He was also the first NFL player to rush for over 10,000 yards.

He told me, "Make sure when anyone tackles you he remembers how much it hurts." He lived by that philosophy and I always followed that advice.

— John Mackey, 1999

Brown's 1,863 rushing yards in the 1963 season remains a Cleveland franchise record. It is currently the oldest franchise record for rushing yards out of all 32 NFL teams. His average of 133 yards per game that season is exceeded only by O. J. Simpson's 1973 season. While others have compiled more prodigious statistics, when viewing Brown's standing in the game, his style of running must be considered along with statistical measures. He was very difficult to tackle (shown by his leading 5.2 yards per carry), often requiring more than one defender to bring him down.[24]

Brown retired in July 1966,[25][26] after nine seasons, as the NFL's all-time leading rusher. He held the record of 12,312 yards until it was broken by Walter Payton on October 7, 1984, during Payton's 10th NFL season. Brown is still the Browns' all-time leading rusher.[27] As of 2018 Brown is 11th on the all-time rushing list.[28]

During Brown's career, Cleveland won the NFL championship in 1964 and were runners-up in 1957 and 1965, his rookie and final season, respectively. In the 1964 championship game, Brown rushed 27 times for 114 yards and caught 3 passes for 37.[29]

Acting career

Early films

Brown began his acting career before the 1964 season, playing a buffalo soldier in a Western action film called Rio Conchos.[30] The film premiered at Cleveland's Hippodrome theater on October 23, with Brown and many of his teammates in attendance. The reaction was lukewarm. Brown, one reviewer said, was a serviceable actor, but the movie's overcooked plotting and implausibility amounted to "a vigorous melodrama for the unsqueamish."[31]

MGM

In early 1966, Brown was shooting his second film in London.[32] MGM's The Dirty Dozen cast Brown as Robert Jefferson, one of 12 convicts sent to France during World War II to assassinate German officers meeting at a castle near Rennes in Brittany before the D-Day invasion. Production delays due to bad weather meant he missed at least the first part of training camp on the campus of Hiram College, which annoyed Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell, who threatened to fine Brown $1,500 (equivalent to $14,100 in 2023) for every week of camp he missed.[33] Brown, who had previously said that 1966 would be his last season, the final year of a three-year contract,[34] announced his retirement, instead.[25][26][30]

Brown went on to play a villain in a 1967 episode of I Spy called "Cops and Robbers".

Dirty Dozen was a huge hit and MGM signed him to a multi-film contract. His second film for the studio was Dark of the Sun (1968), an action movie set in the Congo where he played a mercenary who was Rod Taylor's best friend.

Ice Station Zebra (1968) was also for MGM, an expensive adventure movie based on a novel by Alistair MacLean where Brown supported Rock Hudson, Patrick McGoohan, and Ernest Borgnine.

Leading man

MGM cast Brown in his first lead role in The Split (1968), based on a Parker novel by Donald E. Westlake. He was paid $125,000 for the role.[35]

Brown followed it with Riot (1969), a prison film for MGM. Both it and The Split were solid hits at the box office. Biographer Mike Freeman credits Brown with becoming "the first black action star", due to roles such as the Marine captain he portrayed in the hit 1968 film Ice Station Zebra.[36]

Brown went to 20th Century Fox for 100 Rifles (1969). Brown was billed over co stars Raquel Welch and Burt Reynolds and had a love scene with Welch, one of the first interracial love scenes.[37] Raquel Welch reflected on the scene in Spike Lee's Jim Brown: All-American.

Brown had a change of pace with Kenner (1969) at MGM, an adventure film partly set in India where Brown plays a man who befriends a young boy. For the same studio, he starred as a sheriff in ... tick ... tick ... tick ... (1970) which was another hit.

Brown appeared in The Grasshopper (1970), a drama for National General Pictures where he played an ex-football player who becomes the lover of Jacqueline Bisset. More typical was El Condor (1970), a Western shot in Spain by John Guillermin, also for National General.

Brown starred in several of the blaxploitation genre: Slaughter (1972), a huge hit for AIP; Black Gunn (1972) for Columbia; Slaughter's Big Rip-Off (1973); The Slams (1973), back at MGM; I Escaped from Devil's Island (1973); and Three the Hard Way (1974) with Fred Williamson and Jim Kelly. He spoofed his own image in the role of "Slammer" in I'm Gonna Git You Sucka (1988) and Hammer, Slammer, & Slade, a television pilot released as a made-for-television film.

He did a spaghetti Western with Williamson, Take a Hard Ride (1975). The popularity of blaxploitation ebbed in the mid-70s and Brown made fewer films.

Late 1970s through to present day

Brown appeared in Fingers (1978), the directorial debut of James Toback.

His 1980s appearances were mostly on television. Brown appeared in some TV shows including Knight Rider in the season-three premiere episode "Knight of the Drones". Brown appeared alongside fellow former football player Joe Namath on The A-Team episode "Quarterback Sneak".[38] Brown also appeared on CHiPs, episodes one and two, in season three, as a pickpocket on roller skates.

He appeared opposite Arnold Schwarzenegger in 1987's The Running Man, an adaptation of a Stephen King novel, as Fireball, and had a cameo in the spoof I'm Gonna Git You Sucka (1988).

Brown appeared in Mars Attacks! (1996) and Sucker Free City (2004) and played a defensive coach, Montezuma Monroe, in Any Given Sunday (1999).

Other post-football activities

Brown posed in the nude for the September 1974 issue of Playgirl magazine, and is one of the rare celebrities to allow full-frontal nude pictures to be used.[39] Brown also worked as a color analyst on NFL telecasts for CBS in 1978, teaming with Vin Scully and George Allen.[40]

In 1983, 17 years after retiring from professional football, Brown mused about coming out of retirement to play for the Los Angeles Raiders when it appeared that Pittsburgh Steelers running back Franco Harris would break Brown's all-time rushing record.[41] Brown disliked Harris' style of running, criticizing the Steelers' running back's tendency to run out of bounds, a marked contrast to Brown's approach of fighting for every yard and taking on the approaching tackler.[citation needed] Eventually, Walter Payton of the Chicago Bears broke the record on October 7, 1984, with Brown having ended thoughts of a comeback. Harris himself, who retired after the 1984 season after playing eight games with the Seattle Seahawks, fell short of Brown's mark. Following Harris's last season, in that January, a challenge between Brown and Harris in a 40-yard dash was nationally televised. Brown, at 48 years old, was certain he could beat Harris, though Harris was only 34 years old and just ending his elite career. Harris clocked in at 5.16 seconds, and Brown in at 5.72 seconds, pulling up in towards the end of the race clutching his hamstring.[42]

In 1965, Brown was the first black televised boxing announcer when he announced a televised boxing match in the United States, for the Terrell–Chuvalo fight,[43][44] and is also credited with then first suggesting a career in boxing promotion to Bob Arum.[45]

Brown's autobiography, published in 1989 by Zebra Books, was titled Out of Bounds and was co-written with Steve Delsohn.[46] He was a subject of the book Jim: The Author's Self-Centered Memoir of the Great Jim Brown, by James Toback.

In 1993, Brown was hired as a color commentator for the Ultimate Fighting Championship, a role he occupied for the first six pay-per-view events.

In 1988, Brown founded the Amer-I-Can Program. He currently works with juveniles caught up in the gang scene in Los Angeles and Cleveland through this Amer-I-Can program.[47] It is a life-management skills organization that operates in inner cities and prisons.

In 2002, film director Spike Lee released the film Jim Brown: All-American, a retrospective on Brown's professional career and personal life.

In 2008, Brown initiated a lawsuit against Sony and EA Sports for using his likeness in the Madden NFL video game series. He claimed that he "never signed away any rights that would allow his likeness to be used".[48]

As of 2008, Brown was serving as an executive advisor to the Browns, assisting to build relationships with the team's players and to further enhance the NFL's wide range of sponsored programs through the team's player programs department.[49]

On May 29, 2013, Brown was named a special advisor to the Browns.[50]

Brown is also a part-owner of the New York Lizards of Major League Lacrosse, joining a group of investors in the purchase of the team in 2012.[51]

On October 11, 2018, Brown along with Kanye West met with President Donald Trump to discuss the state of America, among other topics.[52]

Personal life and legal troubles

Brown married his first wife Sue Brown (née Jones) in September 1959.[53] She sued for divorce in 1968, charging him with "gross neglect." Together they had three children, twins born 1960, and a son born 1962.[54] Their divorce was finalized in 1972.[55] Brown was ordered to pay $2,500 per month in alimony and $100 per week for child support.[56]

In 1965, Brown was arrested in his hotel room for assault and battery against an 18-year-old named Brenda Ayres; he was later acquitted of those charges.[53] A year later, he fought paternity allegations that he fathered Brenda Ayres' child.[57]

In 1968, Brown was charged with assault with intent to commit murder after model Eva Bohn-Chin was found beneath the balcony of Brown's second-floor apartment.[58] The charges were later dismissed after Bohn-Chin refused to cooperate with the prosecutor's office. Brown was also ordered to pay a $300 fine for striking a deputy sheriff involved in the investigation during the incident. In Brown's autobiography, he stated that Bohn-Chin was angry and jealous over an affair he had been having with Gloria Steinem, and this argument is what led to the "misunderstanding with the police".[59]

In 1970, Brown was found not guilty of assault and battery, the charges stemming from a road-rage incident that had occurred in 1969.[60]

In December 1973, Brown proposed to 18-year-old Diane Stanley, a Clark College student he met in Acapulco, Mexico, in April of that year.[61][62] They broke off their engagement in 1974.[63]

In 1975, Brown was convicted of misdemeanor battery for beating and choking his golfing partner, Frank Snow. He was sentenced to one day in jail, two years' probation, and a fine of $500.[64][65]

In 1985, Brown was charged with raping a 33-year-old woman.[66] The charges were later dismissed.[67]

In 1986, Brown was arrested for assaulting his fiancée Debra Clark.[68] Clark refused to press charges, though, and Brown was released.[69]

Brown married his second wife Monique Brown in 1997; they have two children.[70] In 1999, Brown was arrested and charged with making terroristic threats toward his wife. Later that year, he was found guilty of vandalism for smashing his wife's car with a shovel.[71] He was sentenced to three years' probation, one year of domestic violence counseling, and 400 hours of community service or 40 hours on a work crew along with a $1,800 fine.[72] Brown ignored the terms of his sentence and in 2000 was sentenced to six months in jail, which he began serving in 2002 after refusing the court-ordered counseling and community service.[73] He was released after three months.[74][75]

Sporting accolades

Brown's memorable professional career led to his induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1971. His football accomplishments at Syracuse garnered him a berth in the College Football Hall of Fame.

Jim Brown also earned a spot in the Lacrosse Hall of Fame, giving him a rare triple crown of sorts.

In 118 career games, Brown averaged 104.3 yards per game and 5.2 yards per carry; only Barry Sanders (99.8 yards per game and 5.0 yards per carry)[76] comes close to these totals. For example, Hall of Famer Walter Payton averaged only 88 yards per game during his career with a 4.4 yards-per-carry average. Emmitt Smith averaged only 81.2 yards per game with a 4.2 yards-per-carry average.[77] Brown held the yards-per-carry record by a running back (minimum 750 carries) from his retirement in 1965 until Jamaal Charles broke the record in 2012, but he still remains in 2nd place all-time over 50 years after his last NFL game.

The only top-10 all-time rusher who even approaches Brown's totals, Barry Sanders, posted a career average of 99.8 yards per game and 5.0 yards per carry. However, Barry Sanders' father, William, was frequently quoted as saying that Jim Brown was "the best I've ever seen."[78]

Brown currently holds NFL records for: - most games with 24 or more points in a career (6) - highest career touchdowns per game average (1.068) - most career games with three or more touchdowns (14) - most games with four or more touchdowns in a career (6) - most seasons leading the league in rushing attempts (6) - most seasons leading the league in rushing yards (8) - highest career rushing yards-per-game average (104.3) - most seasons leading the league in touchdowns (5) - most seasons leading the league in yards from scrimmage (6) - highest average yards from scrimmage per game in a career (125.52) - most seasons leading the league in combined net yards (5)

In 2002, The Sporting News selected him as the greatest football player of all time,[2] as did the New York Daily News in 2014.[79] On November 4, 2010, Brown was chosen by NFL Network's NFL Films production The Top 100: NFL's Greatest Players as the second-greatest player in NFL history, behind only Jerry Rice. In November 2019, he was selected as one of the twelve running backs on the NFL 100th Anniversary All-Time Team.[80]

On January 13, 2020, Brown was named the greatest college football player of all time by ESPN, during a ceremony at the College Football Playoff National Championship Game celebrating the 150th anniversary of college football.

Cultural depictions

Portrayals

Brown was portrayed by Darrin Henson in the 2008 film The Express, which is about the life of Ernie Davis, also a former Syracuse running back.

In the stage play One Night in Miami, first performed in 2013, Brown was portrayed by David Ajala. In its 2020 film adaptation, he is played by Aldis Hodge.

Brown appears as a minor character in Quentin Tarantino's 2021 novelization of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

NFL career statistics

| Legend | |

|---|---|

| AP NFL MVP | |

| NFL champion | |

| NFL record | |

| Led the league | |

| Bold | Career high |

| Year | Team | GP | Rushing | Receiving | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Att | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | Y/G | A/G | Rec | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | |||

| 1957 | CLE | 12 | 202 | 942 | 4.7 | 69 | 9 | 78.5 | 16.8 | 16 | 55 | 3.4 | 12 | 1 |

| 1958 | CLE | 12 | 257 | 1,527 | 5.9 | 65 | 17 | 127.3 | 21.4 | 16 | 138 | 8.6 | 46 | 1 |

| 1959 | CLE | 12 | 290 | 1,329 | 4.6 | 70 | 14 | 110.8 | 24.2 | 24 | 190 | 7.9 | 25 | 0 |

| 1960 | CLE | 12 | 215 | 1,257 | 5.8 | 71 | 9 | 104.8 | 17.9 | 19 | 204 | 10.7 | 37 | 2 |

| 1961 | CLE | 14 | 305 | 1,408 | 4.6 | 38 | 8 | 100.6 | 21.8 | 46 | 459 | 10.0 | 77 | 2 |

| 1962 | CLE | 14 | 230 | 996 | 4.3 | 31 | 13 | 71.1 | 16.4 | 47 | 517 | 11.0 | 53 | 5 |

| 1963 | CLE | 14 | 291 | 1,863 | 6.4 | 80 | 12 | 133.1 | 20.8 | 24 | 268 | 11.2 | 83 | 3 |

| 1964 | CLE | 14 | 280 | 1,446 | 5.2 | 71 | 7 | 103.3 | 20.0 | 36 | 340 | 9.4 | 40 | 2 |

| 1965 | CLE | 14 | 289 | 1,544 | 5.3 | 67 | 17 | 110.3 | 20.6 | 34 | 328 | 9.6 | 32 | 4 |

| Career[81] | 118 | 2,359 | 12,312 | 5.2 | 80 | 106 | 104.3 | 20.0 | 262 | 2,499 | 9.5 | 83 | 20 | |

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | Rio Conchos | Sergeant Franklyn | First film |

| 1967 | I Spy | Tommy | Episode: "Cops and Robbers" |

| 1967 | The Dirty Dozen | Robert Jefferson | |

| 1968 | Dark of the Sun | Ruffo | Lead |

| Ice Station Zebra | Captain Leslie Anders | ||

| The Split | McClain | Lead | |

| 1969 | Riot | Cully Briston | Lead |

| 100 Rifles | Sheriff Lyedecker | Lead | |

| Kenner | Roy Kenner | Lead | |

| 1970 | ...tick...tick...tick... | Jimmy Price | Lead |

| El Condor | Luke | Lead | |

| The Grasshopper | Tommy Marcott | ||

| 1972 | Slaughter | Slaughter | Lead |

| Black Gunn | Gunn | Lead | |

| 1973 | Slaughter's Big Rip-Off | Slaughter | Lead |

| The Slams | Curtis Hook | Lead | |

| 1974 | I Escaped from Devil's Island | Le Bras | Lead |

| Three the Hard Way | Jimmy Lait | Lead | |

| 1975 | Take a Hard Ride | Pike | Lead |

| 1977 | Police Story | Pete Gerard | Episode: "End of the Line" |

| 1977 | Kid Vengeance | Isaac | |

| 1978 | Fingers | "Dreems" | |

| Pacific Inferno | Clyde Preston | Lead | |

| 1982 | One Down, Two to Go | "J" | Lead |

| 1979–1983 | CHiPs | Romo / Parkdale H.S. Shop Teacher John Casey | 3 episodes |

| 1984 | Knight Rider | C.J. Jackson | Episode: "Knight of the Drones" |

| 1983–1984 | T. J. Hooker | Detective Jim Cody / Frank Barnett | 2 episodes |

| 1984 | Cover Up | Calvin Tyler | Episode: "Midnight Highway" |

| 1985 | Lady Blue | Stoker | pilot episode |

| 1986 | The A-Team | "Steamroller" | Episode: "Quarterback Sneak" |

| 1987 | The Running Man | "Fireball" | |

| 1988 | I'm Gonna Git You Sucka | "Slammer" | |

| 1989 | L.A. Heat | Captain | |

| Crack House | Steadman | ||

| 1990 | Killing American Style | "Sunset" | |

| Twisted Justice | Morris | ||

| Hammer, Slammer, & Slade | "Slammer" | ||

| 1992 | The Divine Enforcer | King | |

| 1996 | Original Gangstas | Jake Trevor | |

| Mars Attacks! | Byron Williams | ||

| 1998 | He Got Game | Spivey | |

| Small Soldiers | Butch Meathook | Voice | |

| 1999 | New Jersey Turnpikes | Unknown | |

| Any Given Sunday | Montezuma Monroe | ||

| 2002 | On the Edge | Chad Grant | |

| 2004 | She Hate Me | Geronimo Armstrong | |

| Sucker Free City | Don Strickland | ||

| 2005 | Animal | Berwell | |

| 2006 | Sideliners | Monroe | |

| 2010 | Dream Street | Unknown | |

| 2014 | Draft Day | Himself | Cameo |

| 2016 | Unsung Hollywood | Himself | documentary |

| 2019 | The Black Godfather | Himself | documentary |

See also

- Most consecutive starts by a fullback

- List of National Football League rushing yards leaders

- List of National Football League rushing champions

- List of NCAA major college yearly punt and kickoff return leaders

Notes

- ^ Brown later matched his own record with 237 yards against the Philadelphia Eagles in 1961.[22]

References

- ^ "Joe Montana, Jim Brown on Hall of Fame 50th Anniversary Team". NFL.com. July 29, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ a b "Football's 100 Greatest Players: No. 1 Jim Brown". The Sporting News. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ^ Top 5 ranked men's lacrosse players of all time. rookieroad.com. (n.d.). Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.rookieroad.com/lacrosse/top-5-ranked-mens-players-of-all-time/

- ^ “Jim Brown, Lacrosse, 1955-57.” Syracuse University Athletics, https://cuse.com/sports/2006/9/26/brownlaxbio.

- ^ Top 10 Best Lacrosse Players of All Time - SportsGeeks. (2022). Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://sportsgeeks.net/best-lacrosse-players-of-all-time/

- ^ PREMIER LACROSSE LEAGUE ANNOUNCES PARTNERSHIP WITH LACROSSE LEGEND & NFL HALL OF FAMER JIM BROWN - Premier Lacrosse League. (2022). Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://premierlacrosseleague.com/articles/jimbrown

- ^ "NFL Yards per Rushing Attempt Career Leaders (since 1946)". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ "The 150 greatest players in college football's 150-year history". ESPN. January 14, 2020. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Chris. "Jim Brown honored at National Championship game as greatest college football player of all time". Cleveland19. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Valentine, Natalie (April 1, 1996). "Jim Brown". Syracuse University Magazine. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen. "FILM REVIEW; Jim Brown as Football Legend, Sex Symbol and Husband Archived August 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine", The New York Times, March 22, 2002. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ Bob Rubin (November 25, 1983). "Remember Jim Brown, lacrosse star?". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "The Cotton Bowl 1957". Mmbolding.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ "T&FN - Past Results". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Vecsey, George (February 24, 2017). "Some Rules Changes Are Actually Good". National Sports Media Association. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Evans, Eric. A Short Pre-game (PDF) (Report). p. 8. Retrieved March 3, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mann, Ronald. Bouncing Back: How to Recover When Life Knocks You Down, page 19 Archived October 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine (Wordclay, 2010).

- ^ McPhee, John (March 22, 2010). "Pioneer". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d News staff (June 10, 2016). "Jim Brown '57, Maj. Gen. Peggy Combs '85 Inducted into US Army ROTC Hall of Fame". Syracuse University News. Syracuse, NY. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ "Jim Brown NFL & AFL Football Statistics". Pro-Football-Reference.com. February 17, 1936. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Zeitlan, Arnold (November 25, 1957). "Four TDs For Brown, Cleveland Wins, 45–31". Alton Evening Telegraph. Associated Press. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Exner, Rich (November 19, 2009). "This Day in Browns History: Jim Brown ties NFL record with 237 yards rushing". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ a b "1958 Official National Football Statistics", Pro All Stars 1959 Pro Football. New York: Maco Publishing, 1959; pp. 90-91.

- ^ Schwartz, Larry. ""Jim Brown Was Hard To Bring Down" Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, ESPN. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "Jim Brown announces retirement; Collier plans to readjust offense". Youngstown Vindicator. Ohio. Associated Press. July 14, 1966. p. 31. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "Jim Brown retires from pro football". Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. July 14, 1966. p. 16. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Smith's firm hold on coveted record | Pro Football Hall of Fame Official Site". www.profootballhof.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "NFL History – Rushing Leaders" Archived October 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, ESPN, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ "Championship - Baltimore Colts at Cleveland Browns - December 27th, 1964". Pro-Football-Reference.com.

- ^ a b Pluto 1997, p. 179.

- ^ Batdorff, Emerson (October 24, 1964). "Brown Does OK in 'Conchos'". Cleveland Plain Dealer. p. 17.

- ^ Pluto 1997, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Pluto 1997, pp. 178–179.

- ^ "Brown backs off". Toledo Blade. Ohio. January 3, 1966. p. 14. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ TUSHER, WILLIAM (January 28, 1968). "Jim Brown's End Run Around Race Prejudice". Los Angeles Times. p. d11.

- ^ Freeman, Mike. Jim Brown: The Fierce Life of an American Hero Archived November 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, page 17 (HarperCollins 2007).

- ^ Hollie I. West (March 26, 1969). "Jim Brown: Crisp and Direct as a Fullback". The Washington Post and Times-Herald. p. B1.

- ^ "Quarterback Sneak" Archived February 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (episode of The A-Team) at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ Harrington, Amy (March 26, 2015). "Celebrities in Playgirl". Fox News. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ Langdon, Jerry (September 24, 1978). "CBS goes to the 3-man lineup for NFL football games". Poughkeepsie Journal. Gannett News Service. p. 10D.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (November 21, 1983). "JIM BROWN"S BAD DREAM". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ "Harris Beats Brown at 40 Yards, Wins 2-Day Competition". Los Angeles Times. January 19, 1985. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ "Jimmy Brown A Mike Man". Press and Sun-Bulletin. New York. October 14, 1965. p. 19. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Hauser, Thomas Archived August 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, Open Road Media, 2012, page 145. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Iole, Kevin Archived August 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine "How NFL legend Jim Brown pushed Bob Arum into boxing promotion", Yahoo! Sports, March 28, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Mergan (September 15, 1989). "Jim Brown's Tale of Sex, Football, Sex, Life and Sex". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Amer-I-Can Program". Amer-i-can.org. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ "Football great Jim Brown suing EA, Sony". Yahoo! Video Games. Archived from the original on August 10, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ "Cleveland Browns Front Office". Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ^ "Jim Brown rejoins Cleveland Browns as special adviser". NFL.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ "Investors Purchase Lizards; Jim Brown Among Owners". Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Shreckinger, Ben (October 11, 2018). "Donald Trump and Kanye West remix the government". Politico. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Spicy Trial of Jime Brown" Grid star Denies Sex Acts". Jet: 16. August 5, 1965. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Jim Brown's Wife Sues For Divorce, Charges Neglect". Jet: 47. September 12, 1968. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Jim Brown's Wife Gets Divorce; Says Brown's 'A Millionaire'". Jet: 54. January 20, 1972. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Jim Brown Ordered To Pay $2,500 A Month Alimony". Jet: 13. June 29, 1972. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Paternity Rap 'Ridiculous' Claims Jim Brown". Jet: 57. February 17, 1966. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Megan (September 15, 1989). "Jim Brown's Tale of Sex, Football, Sex, Life and Sex". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Jim Brown Had More Than a Few Issues Off the Field With Both Women and Men". The Big Lead. February 17, 2016. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Zirin, Dave. "Toxic: Jim Brown, Manhood and Violence Against Women". Cleveland Scene. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Mitchell, Grayson (February 14, 1974). "Jim Brown Talks About The Girl He Will Marry". Jet: 19–23. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Jim Brown's Wedding Date Set For August 3 In Philly". Jet: 46. April 4, 1974. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Jim Brown's Fiancee Breaks Off Engagement And Returns His Ring". Jet: 9. September 19, 1974. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Headliners: Joan Little, Black Panthers, Jim Brown". The Afro American. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2016 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Bolch, Ben (September 4, 2020). "Pioneering Black California golfer Frank Snow, a mentor of Tiger Woods, dies at 78". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ STEWART, ROBERT W. (March 19, 1985). "Jim Brown Will Be Charged With Rape". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Shah, Diane K. "What's The Matter With Jim Brown?". The Stacks. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Jim Brown Arrested For Battering His Fiancee". Jet: 60. September 8, 1986. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Jim Brown Faces Battery Charge". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Gitlin, Marty (2014). Jim Brown:: Football Great & Actor. North Mankato, Minnesota: ABDO Publishing Company. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-62968-144-3. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "USATODAY.com – True manhood and perspective elude Brown". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, John L. (August 28, 1999). "Spousal Abuse Trial of Jim Brown Opens". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Reich, Kenneth (March 14, 2002). "Jim Brown Rejects Judge's Offer, Is Jailed in Domestic Violence Case". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Brown completes jail term". USA Today. Associated Press. July 4, 2002. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022.

- ^ Freeman, Mike (2006). Jim Brown: The Fierce Life of an American Hero. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 12. ISBN 9780061745942.

- ^ "NFL Rushing Yards per Game Career Leaders". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ "NFL Career Rushing Yards Leaders". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Roberts, M.B. "Sanders' humility makes him distinctive". ESPN Classic. Archived from the original on February 28, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Myers, Gary (December 3, 2014). "NFL Top 50: Jim Brown is best player in league history, edges Giants' Lawrence Taylor in Daily News' rankings (Nos. 1–10)". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ "NFL 100 All-Time Team running backs revealed - NFL.com". NFL.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ "Jim Brown Stats". pro-football-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

Further reading

- Jim Brown; Myron Cope (1964). Off My Chest. Doubleday. (autobiography)

- Jim Brown; Steve Delsohn (1989). Out of Bounds. Zebra Books. p. 380. (autobiography)

- Freeman, Mike (2006). Jim Brown: The Fierce Life of an American Hero. Harper Collins World.

- Toback, James (2009) [1971]. Jim: The Author's Self-Centered Memoir on the Great Jim Brown. Doubleday and Company, Inc. (1971) & Rat Press (March 3, 2009).

- Pluto, Terry (1997). Browns Town 1964: Cleveland Browns and the 1964 Championship. Cleveland: Gray & Company. ISBN 978-1-886228-72-6.

External links

- Jim Brown at the Pro Football Hall of Fame

- Jim Brown at the College Football Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from NFL.com · Pro Football Reference ·

- Jim Brown at IMDb

- Jim Brown at AllMovie

- National Lacrosse Hall of Fame profile

- Amer-I-Can Program

- 1936 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- Male actors from Georgia (U.S. state)

- African-American activists

- African-American basketball players

- American male film actors

- African-American players of American football

- African-American sports announcers

- African-American sports journalists

- All-American college football players

- American football fullbacks

- American lacrosse players

- Basketball players from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Cleveland Browns players

- College Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Eastern Conference Pro Bowl players

- National Football League announcers

- National Football League players with retired numbers

- People from St. Simons, Georgia

- People from Manhasset, New York

- Players of American football from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Pro Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Male Spaghetti Western actors

- Syracuse Nationals draft picks

- Syracuse Orange football players

- Syracuse Orange men's lacrosse players

- Syracuse Orange men's basketball players

- African-American male actors

- American male television actors

- Manhasset High School alumni

- American men's basketball players

- Playgirl Men of the Month

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- 20th-century African-American sportspeople

- 21st-century African-American people

- National Football League Most Valuable Player Award winners