MERS-related coronavirus

| MERS-CoV | |

|---|---|

| |

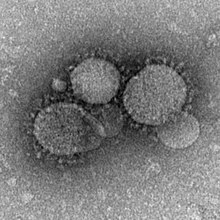

| MERS-CoV particles as seen by negative stain electron microscopy. Virions contain characteristic club-like projections emanating from the viral membrane. | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group IV ((+)ssRNA)

|

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | MERS-CoV

|

The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV),[1] also termed EMC/2012 (HCoV-EMC/2012), is positive-sense, single-stranded RNA novel species of the genus Betacoronavirus.

First called novel coronavirus 2012 or simply novel coronavirus, it was first reported in 2012 after genome sequencing of a virus isolated from sputum samples from patients who fell ill in a 2012 outbreak of a new flu.

As of June 2014, MERS-CoV cases have been reported in 22 countries, including Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Jordan, Qatar, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Turkey, Oman, Algeria, Bangladesh, Indonesia (none was confirmed), Austria,[2] the United Kingdom, and the United States.[3] [4] Almost all cases are somehow linked to Saudi Arabia.[5] In the same article it was reported that Saudi authorities' errors in response to MERS-CoV were a contributing factor to the spread of this deadly virus.[5]

Virology

The virus MERS-CoV is a new member of the beta group of coronavirus, Betacoronavirus, lineage C. MERS-CoV genomes are phylogenetically classified into two clades, clade A and B. The earliest cases of MERS were of clade A clusters (EMC/2012 and Jordan-N3/2012), and new cases are genetically distinct (clade B).[6]

MERS-CoV is distinct from SARS and distinct from the common-cold coronavirus and known endemic human betacoronaviruses HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1.[7] Until 23 May 2013, MERS-CoV had frequently been referred to as a SARS-like virus,[8] or simply the novel coronavirus, and early it was referred to colloquially on messageboards as the "Saudi SARS".

Origin

The first confirmed case was reported in Saudi Arabia 2012.[7] Egyptian virologist Dr. Ali Mohamed Zaki isolated and identified a previously unknown coronavirus from the man's lungs.[9][10][11] Dr. Zaki then posted his findings on 24 September 2012 on ProMED-mail.[10][12][12] The isolated cells showed cytopathic effects (CPE), in the form of rounding and syncytia formation.[12]

A second case was found in September 2012. A 49-year-old male living in Qatar presented similar flu symptoms, and a sequence of the virus was nearly identical to that of the first case.[7] In November 2012, similar cases appeared in Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Additional cases were noted, with deaths associated, and rapid research and monitoring of this novel coronavirus began.

It is not certain whether the infections are the result of a single zoonotic event with subsequent human-to-human transmission, or if the multiple geographic sites of infection represent multiple zoonotic events from a common unknown source.

A study by Ziad Memish of Riyadh University and colleagues suggests that the virus arose sometime between July 2007 and June 2012, with perhaps as many as 7 separate zoonotic transmissions. Among animal reservoirs, CoV has a large genetic diversity yet the samples from patients suggest a similar genome, and therefore common source, though the data are limited. It has been determined through molecular clock analysis, that viruses from the EMC/2012 and England/Qatar/2012 date to early 2011 suggesting that these cases are descended from a single zoonotic event. It would appear the MERS-CoV has been circulating in the human population for greater than one year without detection and suggests independent transmission from an unknown source.[13][14]

Tropism

In humans, the virus has a strong tropism for nonciliated bronchial epithelial cells, and it has been shown to effectively evade the innate immune responses and antagonize interferon (IFN) production in these cells. This tropism is unique in that most respiratory viruses target ciliated cells.[15][16]

Due to the clinical similarity between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, it was proposed that they may use the same cellular receptor; the exopeptidase, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).[17] However, it was later discovered that neutralization of ACE2 by recombinant antibodies does not prevent MERS-CoV infection.[18] Further research identified dipeptyl peptidase 4 (DPP4; also known as CD26) as a functional cellular receptor for MERS-CoV.[16] Unlike other known coronavirus receptors, the enzymatic activity of DPP4 is not required for infection. As would be expected, the amino acid sequence of DPP4 is highly conserved across species and is expressed in the human bronchial epithelium and kidneys.[16][19] Bat DPP4 genes appear to have been subject to a high degree of adaptive evolution as a response to coronavirus infections, so the lineage leading to MERS-CoV may have circulated in bat populations for a long period of time before being transmitted to people.[20]

Transmission

On 13 February 2013, the World Health Organization stated "the risk of sustained person-to-person transmission appears to be very low."[21] The cells MERS-CoV infects in the lungs only account for 20% of respiratory epithelial cells, so a large number of virions are likely needed to be inhaled to cause infection.[19]

As of 29 May 2013[update], the WHO warned that the MERS-CoV virus is a "threat to entire world."[22] However, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, stated that as of now MERS-CoV "does not spread in a sustained person to person way at all." Dr. Fauci stated that there is potential danger in that it is possible for the virus to mutate into a strain that does transmit from person to person.[23]

The infection of healthcare workers (HCW) has led to concerns of human to human transmission.[24]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) list MERS as transmissible from human-to-human. From their FAQ, in answer to the question "Does MERS-CoV spread from person to person?", they answer "MERS-CoV has been shown to spread between people who are in close contact. Transmission from infected patients to healthcare personnel has also been observed. Clusters of cases in several countries are being investigated."[25] There is also a New York Times article which provides some correlative context for this.[26]

However on the 28th of May, the CDC revealed that the Illinois man who was originally thought to have been the first incidence of person to person spread (from the Indiana man at a business meeting), had in fact tested negative for MERS-CoV. After completing additional and more definitive tests using a neutralising antibody assay, experts at the CDC have concluded that the Indiana patient did not spread the virus to the Illinois patient. Tests concluded that the Illinois man had not been previously infected. It is possible for silent MERS to occur, this is when the patient does not develop symptoms. Early research has shown that up to 20% of cases show no signs of active infection but have MERS-CoV antibodies in their blood.[27]

Natural reservoir

Early research suggested the virus is related to one found in the Egyptian tomb bat. In September 2012 Ron Fouchier speculated that the virus might have originated in bats.[28] Work by epidemiologist Ian Lipkin of Columbia University in New York showed that the virus isolated from a bat looked to be a match to the virus found in humans.[29][30] [31] 2c betacoronaviruses were detected in Nycteris bats in Ghana and Pipistrellus bats in Europe that are phylogenetically related to the MERS-CoV virus.[32]

Recent work links camels to the virus. An ahead-of-print dispatch for the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases records research showing the coronavirus infection in dromedary camel calves and adults, 99.9% matching to the genomes of human clade B MERS-CoV.[33]

At least one person who has fallen sick with MERS was known to have come into contact with camels or recently drank camel milk.[34]

On 9 August 2013, a report in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases showed that 50 out of 50 (100%) blood serum from Omani camels and 15 of 105 (14%) from Spanish camels had protein-specific antibodies against the MERS-CoV spike protein. Blood serum from European sheep, goats, cattle, and other camelids had no such antibodies.[35] Countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates produce and consume large amounts of camel meat. The possibility exists that African or Australian bats harbor the virus and transmit it to camels. Imported camels from these regions might have carried the virus to the Middle East.[36]

In 2013 MERS-CoV was identified in three members of a dromedary camel herd held in a Qatar barn, which was linked to two confirmed human cases who have since recovered. The presence of MERS-CoV in the camels was confirmed by the National Institute of Public Health and Environment (RIVM) of the Ministry of Health and the Erasmus Medical Center (WHO Collaborating Center), the Netherlands. None of the camels showed any sign of disease when the samples were collected. The Qatar Supreme Council of Health advised in November 2013 that people with underlying health conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, respiratory disease, the immunosuppressed, and the elderly, avoid any close animal contacts when visiting farms and markets, and to practice good hygiene, such as washing hands.[37]

A further study on dromedary camels from Saudi Arabia published in December 2013 revealed the presence of MERS-CoV in 90% of the evaluated dromedary camels (310), suggesting that dromedary camels not only could be the main reservoir of MERS-CoV, but also the animal source of MERS.[38]

According to the 27 March 2014 MERS-CoV summary update, recent studies support that camels serve as the primary source of the MERS-CoV infecting humans, while bats may be the ultimate reservoir of the virus. Evidence includes the frequency with which the virus has been found in camels to which human cases have been exposed, seriological data which shows widespread transmission in camels, and the similarity of the camel CoV to the human CoV.[39]

On 6 June 2014, the Arab News newspaper highlighted the latest research findings in the New England Journal of Medicine in which a 44-year-old Saudi man who kept a herd of nine camels died of MERS in November 2013. His friends said they witnessed him applying a topical medicine to the nose of one of his ill camels—four of them reportedly sick with nasal discharge—seven days before he himself became stricken with MERS. Researchers sequenced the virus found in one of the sick camels and the virus that killed the man, and found that their genomes were identical. In that same article, the Arab News reported that as of 6 June 2014, there have been 689 cases of MERS reported within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia with 283 deaths.[40]

Taxonomy

MERS-CoV is more closely related to the bat coronaviruses HKU4 and HKU5 (lineage 2C) than it is to SARS-CoV (lineage 2B) (2, 9), sharing more than 90% sequence identity with their closest relationships, bat coronaviruses HKU4 and HKU5 and therefore considered to belong to the same species by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

- Mnemonic:

- Taxon identifier:

- Scientific name: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus[1]

- Common name: MERS-CoV

- Synonym: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- Other names:

- novel coronavirus (nCoV)

- London1 novel CoV 2012[41]

- Human Coronavirus Erasmus Medical Center/2012 (HCoV-EMC/2012)

- Rank:

- Lineage:

- › Viruses

- › ssRNA viruses

- › Group: IV; positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses

- › Order: Nidovirales

- › Family: Coronaviridae

- › Subfamily: Coronavirinae

- › Genus: Betacoronavirus[42]

- › Species: Betacoronavirus 1 (commonly called Human coronavirus OC43), Human coronavirus HKU1, Murine coronavirus, Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5, Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9, Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4, MERS-CoV

- › Genus: Betacoronavirus[42]

- › Subfamily: Coronavirinae

- › Family: Coronaviridae

- › Order: Nidovirales

- › Group: IV; positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses

- › ssRNA viruses

Strains:

- Isolate:

- Isolate:

- NCBI

Microbiology

The virus grows readily on Vero cells and LLC-MK2 cells.[12]

Research and patent

Saudi officials had not given permission to Dr. Zaki to send a sample of the virus to Fouchier and they were angered when Fouchier claimed the patent on the full genetic sequence[44] of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.[44]

The editor of The Economist observed, "Concern over security must not slow urgent work. Studying a deadly virus is risky. Not studying it is riskier."[44] Dr. Zaki was fired from his job at the hospital as a result of sharing his sample and findings.[45][46][47][48]

At their annual meeting of the World Health Assembly in May 2013, WHO chief Margaret Chan declared that intellectual property, or patents on strains of new virus, should not impede nations from protecting their citizens by limiting scientific investigations. Deputy Health Minister Ziad Memish raised concerns that scientists who held the patent for the MERS-CoV virus would not allow other scientists to use patented material and were therefore delaying the development of diagnostic tests.[49] Erasmus MC responded that the patent application did not restrict public health research into MERS coronavirus,[50] and that the virus and diagnostic tests were shipped—free of charge—to all that requested such reagents.

Corona Map

There are a number of mapping efforts focused on tracking MERS coronavirus. On 2 May 2014, the Corona Map was launched to track the MERS coronavirus in realtime on the world map. The data is officially reported by WHO or the Ministry of Health of the respective country.[51] HealthMap also tracks case reports with inclusion of news and social media as data sources as part of HealthMap MERS.

See also

- Outbreak

- Super-spreader

- Virulence

- Novel virus

- HCoV-EMC/2012

- London1 novel CoV/2012

- Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4

- Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

References

- ^ a b De Groot RJ; et al. (15 May 2013). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group". Journal of Virology. 87 (14): 7790–2. doi:10.1128/JVI.01244-13. PMC 3700179. PMID 23678167.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-separator=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ "Disease Outbreak News". www.who.int. 8 Oct 2014.

- ^ Roos, Robert (16 Jun 2014). "Bangladesh has first MERS case". cidrap.umn.edu.

- ^ "Patient with deadly MERS virus waited hours in Florida ER". 2014-05-14. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ^ a b Hubbarb, Ben; McNeill Jr., Donald G. (1 July 2014). " "Experts say errors aided deadly virus; Doctors blame response by Saudi authorities for helping MERS spread". International New York Times – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "MERS Coronaviruses in Dromedary Camels, Egypt". June 2014. Retrieved 22 Apr 2014.

- ^ a b c "ECDC Rapid Risk Assessment - Severe respiratory disease associated with a novel coronavirus" (PDF). 19 Feb 2013. Retrieved 22 Apr 2014.

- ^ Saey, Tina Hesman (27 February 2013). "Scientists race to understand deadly new virus: SARS-like infection causes severe illness, but may not spread quickly". Science News. Vol. 183, no. 6. p. 5. doi:10.1002/scin.5591830603.

- ^ Ali Mohamed Zaki; Sander van Boheemen; Theo M. Bestebroer; Albert D.M.E. Osterhaus; Ron A.M. Fouchier (8 November 2012). "Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (19): 1814. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. PMID 23075143.

- ^ a b Falco, Miriam (24 September 2012). "New SARS-like virus poses medical mystery". CNN. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ Dziadosz, Alexander (13 May 2013). "The doctor who discovered a new SARS-like virus says it will probably trigger an epidemic at some point, but not necessarily in its current form ". Reuters. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d "See Also". ProMED-mail. 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ "Full-Genome Deep Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of Novel Human Betacoronavirus - Vol. 19 No. 5 - May 2013 - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2013-05-19. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ Lau SK, Lee P, Tsang AK, Yip CC, Tse H, Lee RA, Molecular epidemiology of human coronavirus OC43 reveals evolution of different genotypes over time and recent emergence of a novel genotype due to natural recombination. J Virol. 2011;85:11325–37. DOIExtract

- ^

Kindler, E.; Jónsdóttir, H. R.; Muth, D.; Hamming, O. J.; Hartmann, R.; Rodriguez, R.; Geffers, R.; Fouchier, R. A.; Drosten, C. (2013). "Efficient Replication of the Novel Human Betacoronavirus EMC on Primary Human Epithelium Highlights Its Zoonotic Potential". MBio. 4 (1): e00611–12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00611-12. PMC 3573664. PMID 23422412.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - ^ a b c Raj, V. S.; Mou, H.; Smits, S. L.; Dekkers, D. H.; Müller, M. A.; Dijkman, R.; Muth, D.; Demmers, J. A.; Zaki, A. (March 2013). "Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC". Nature. 495 (7440): 251–4. doi:10.1038/nature12005. PMID 23486063.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - ^ Jia, HP; Look, DC; Shi, L; Hickey, M; Pewe, L; Netland, J; Farzan, M; Wohlford-Lenane, C; Perlman, S (2005-12-xx). "ACE2 Receptor Expression and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection Depend on Differentiation of Human Airway Epithelia". Journal of Virology. 79 (23). ncbi.nlm.nih.gov: 14614–14621. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005. PMC 1287568. PMID 16282461.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - ^

Müller, MA.; Raj, VS.; Muth, D.; Meyer, B.; Kallies, S.; Smits, SL.; Wollny, R.; Bestebroer, TM.; Specht, S. (11 December 2012). "Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines". MBio. 3 (6): e00515–12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00515-12. PMC 3520110. PMID 23232719.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - ^ a b "Receptor for new coronavirus found". nature.com. 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1186/1743-422X-10-304, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1186/1743-422X-10-304instead. - ^ WHO: Novel coronavirus infection – update (13 February 2013) (accessed 13 February 2013)

- ^ "WHO calls Middle Eastern virus, MERS, 'threat to the entire world' as death toll rises to 27". Daily Mail. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Fauci: New Virus Not Yet a 'threat to the world' (video)". Washington Times. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ Knickmeyer, Ellen; Al Omran, Ahmed (20 Apr 2014). "Concerns Spread as New Saudi MERS Cases Spike". Retrieved 22 Apr 2014.

- ^ "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FAQ on MERS".

- ^ DENISE GRADY (June 19, 2013). "Investigation Follows Trail of a Virus in Hospitals".

- ^ Jonrl Aleccia (28 May 2014). "CDC Backtracks: Illinois Man Didn't Have MERS After All". Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ a b Doucleff, Michaeleen (28 September 2012). "Holy Bat Virus! Genome Hints At Origin Of SARS-Like Virus". NPR. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b Abedine, Saad (13 March 2013). "Death toll from new SARS-like virus climbs to 9". CNN. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ^ Doucleff, Michaeleen (28 September 2012). "Holy Bat Virus! Genome Hints At Origin Of SARS-Like Virus". NPR. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ jobs (2013-08-23). "Deadly coronavirus found in bats : Nature News & Comment". Nature.com. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- ^ a b Augustina Annan; Heather J. Baldwin; Victor Max Corman (March 2013). "Human Betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012–related Viruses in Bats, Ghana and Europe". Emerging Infectious Disease journal - CDC. 19 (3). Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Hemida first=Maged G; Chu, Daniel KW; Poon, Ranawaka; Perera, Mohammad A A; Ng, Hoiyee-Y (Jul 2014). "MERS coronavirus in dromedary camel herd, Saudi Arabia". Retrieved 22 Apr 2014.

The full-genome sequence of MERS-CoV from dromedaries in this study is 99.9% similar to genomes of human clade B MERS-CoV.

{{cite web}}: Missing pipe in:|last=(help) - ^ Roos, Robert (17 Apr 2014). "MERS outbreaks grow; Malaysian case had camel link". Retrieved 22 Apr 2014.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6instead. - ^ "Camels May Transmit New Middle Eastern Virus". 8 August 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ "Three camels hit by MERS coronavirus in Qatar". Qatar Supreme Council of Health. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Hemida, MG (2013). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013". Euro Surveillance. 18 (50).

- ^ "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV)Summary and literature update – as of 27 March2014" (PDF). 27 Mar 2014. Retrieved 24 Apr 2014.

- ^ Mohammed Rasooldeen, Fakeih: 80% drop in MERS infections, Arab News, Vol XXXIX, Number 183, Page 1, 6 June 2014.

- ^ Roos, Robert (25 September 2013). UK agency picks name for new coronavirus isolate (Report). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy (CIDRAP).

- ^ a b c

Bermingham, A.; Chand, MA.; Brown, CS.; Aarons, E.; Tong, C.; Langrish, C.; Hoschler, K.; Brown, K.; Galiano, M. (27 September 2012). "Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012" (PDF). Euro Surveillance. 17 (40): 20290. PMID 23078800.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=9(help) - ^ "New Coronavirus Has Many Potential Hosts, Could Pass from Animals to Humans Repeatedly". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ a b c "Pandemic preparedness: Coming, ready or not". The Economist. 20 April 2013. Cite error: The named reference "Economist20apr2013" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Egyptian Virologist Who Discovered New SARS-Like Virus Fears Its Spread". Mpelembe. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Ian Sample; Mark Smith (15 March 2013). "Coronavirus victim's widow tells of grief as scientists scramble for treatment". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Sample, Ian (15 March 2013). "Coronavirus: Is this the next pandemic?". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Yang, Jennifer (21 October 2012). "How medical sleuths stopped a deadly new SARS-like virus in its tracks". Toronto Star. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "Erasmus MC: no restrictions for public health research into MERS coronavirus" (Press release). Rotterdam: Erasmus MC. 24 May 2013.

- ^ "Corona Map" (Press release). 2 May 2014.