Naltrexone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral hepatic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 5–40% |

| Protein binding | 21% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 4 hours (naltrexone), 13 hours (6-β-naltrexol) |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.939 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H23NO4 |

| Molar mass | 341.401 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 169 °C (336 °F) |

| (verify) | |

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist used primarily in the management of alcohol dependence and opioid dependence. It is marketed in generic form as its hydrochloride salt, naltrexone hydrochloride, and marketed under the trade names Revia and Depade. In some countries including the United States, an extended-release formulation is marketed under the trade name Vivitrol. Also in the US, Methylnaltrexone Bromide, a closely related drug, is marketed as Relistor, for the treatment of Opioid Induced Constipation. It should not be confused with naloxone, which is used in emergency cases of overdose rather than for longer-term dependence control. While both naltrexone and naloxone are full antagonists and will treat an opioid overdose, naltrexone is longer-acting than naloxone, making naloxone a better emergency antidote.

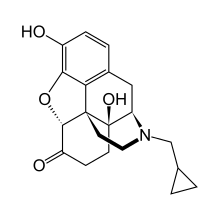

Chemical structure

Naltrexone can be described as a substituted oxymorphone – here the tertiary amine methyl-substituent is replaced with methylcyclopropane.

Naltrexone is the N-cyclopropylmethyl derivative of oxymorphone.

Pharmacology

Naltrexone, and its active metabolite 6-β-naltrexol, are competitive antagonists at μ- and κ-opioid receptors, and to a lesser extent at δ-opioid receptors.[1] The plasma halflife of naltrexone is about 4 hours, for 6-β-naltrexol 13 h. The blockade of opioid receptors is the basis behind its action in the management of opioid dependence—it reversibly blocks or attenuates the effects of opioids.

Its use in alcohol (ethanol) dependence has been studied and has been shown to be effective[2]. Its mechanism of action in this indication is not fully understood, but as an opioid-receptor antagonist it's likely to be due to the modulation of the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway which ethanol is believed to activate.

Naltrexone is metabolised mainly to 6β-naltrexol by the liver enzyme dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. Other metabolites include 2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-6β-naltrexol and 2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-naltrexone. These are then further metabolised by conjugation with glucuronide.

Rapid detoxification

Naltrexone is sometimes used for rapid detoxification ("rapid detox") regimens for opioid dependence. The principle of rapid detoxification is to induce opioid-receptor blockade while the patient is in a state of impaired consciousness so as to attenuate the withdrawal symptoms experienced by the patient. Rapid detoxification under general anaesthesia involves an unconscious patient and requires intubation and external ventilation. Rapid detoxification is also possible under sedation. The rapid detoxification procedure is followed by oral naltrexone daily for up to 12 months for opioid dependence management. There are a number of practitioners who will use a naltrexone implant placed in the lower abdomen, and more rarely, in the posterior to replace the oral naltrexone. This implant procedure has not been shown scientifically to be successful in "curing" the subject of their addiction, though it does provide a better solution than oral naltrexone for medication compliance reasons. Naltrexone implants are made by at least three companies, though none have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration.[2] There is currently scientific disagreement as to whether this procedure should be performed under local or general anesthesia, due to the rapid, and sometimes severe, withdrawal that occurs from the naltrexone displacing the opiates from the receptor sites.

Rapid detoxification has been criticised by some for its questionable efficacy in long-term opioid dependence management.[3] Rapid detoxification has often been misrepresented as a one-off "cure" for opioid dependence, when it is only intended as the initial step in an overall drug rehabilitation regimen. Rapid detoxification is effective for short-term opioid detoxification, but is approximately 10 times more expensive than conventional detoxification procedures. Aftercare can also be an issue,[3] since at least one well-known center in the United States reported that they will remove an implant from any patient arriving in their facility before admission.[citation needed][who?]

The usefulness of naltrexone in opioid dependence is very limited by the low retention in treatment. Like disulfiram in alcohol dependence, it temporarily blocks substance intake and does not affect craving. Though sustained-release preparations of naltrexone has shown rather promising results, it remains a treatment only for a small part of the opioid dependent population, usually the ones with an unusually stable social situation and motivation (e.g. dependent health care professionals). It is given orally by physicians to help reduce the side effects of opiate dependence. Naltrexone implants have been used successfully in Australia for a number of years as part of a long-term protocol for treating opiate addiction. Although Naltrexone treats the physical dependence on opioids, further psychosocial interventions are often required to enable people to maintain abstinence.[4]

Alcohol dependence

The main use of naltrexone is for the treatment of alcohol dependence. After publication of the first two randomized, controlled trials in 1992, a number of studies has confirmed its efficacy in reducing frequency and severity of relapse to drinking.[5] The multi-center COMBINE study has recently proved the usefulness of naltrexone in an ordinary, primary care setting, without adjunct psychotherapy.[6]

The standard regimen is one 50 mg tablet per day. Initial problems of nausea usually disappear after a few days, and other side effects (e.g. heightened liver enzymes) are rare. Drug interactions are not significant, besides the obvious antagonism of opioid analgesics. Naltrexone has two effects on alcohol consumption.[7] The first is to reduce craving while naltrexone is being taken. The second, referred to as the Sinclair Method, occurs when naltrexone is taken in conjunction with normal drinking, and this reduces craving over time. The first effect only persists while the naltrexone is being taken, but the second persists as long as the alcoholic does not drink without first taking naltrexone.

Depot injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol, formerly Vivitrex, but changed after a request by the FDA) was approved by the FDA on April 13, 2006 for the treatment of alcoholism. This version is made by Alkermes, and will be jointly marketed by Cephalon, Inc. The medication is administered by intra-muscular injection and lasts for up to 30 days. Clinical trials for this medication were done with a focus on alcohol, presumably due to the larger number of alcoholics that it could be used to treat; however, Alkermes was asked to run a safety study for the off-label use of the injection for opiate addicts. This was found to be a successful use of the medication in patients who were single drug abusers, though multi-drug abusers would generally decrease their opiate use and increase their use of other drugs (i.e. cocaine) while on the injection. Other studies, however, provide preliminary evidence that naltrexone with the right protocol can be effective in treating cocaine addiction.[8]

Another study released by the National Institute of Health in February 2008 and published in the Archives of General Psychiatry has shown that alcoholics having a certain gene variant of the opioid receptor were far more likely to experience success at cutting back or discontinuing their alcohol intake altogether.[9]

Safety

In alcohol dependence, naltrexone is considered a safe medication. Control of liver values prior to initiation of treatment is recommended. There has been some controversy regarding the use of opioid-receptor antagonists, such as naltrexone, in the long-term management of opioid dependence due to the effect of these agents in sensitising the opioid receptors. That is, after therapy, the opioid receptors continue to have increased sensitivity for a period during which the patient is at increased risk of opioid overdose. This effect reinforces the necessity of monitoring of therapy and provision of patient support measures by medical practitioners.

Other uses

Low dose naltrexone (LDN)

Low dose naltrexone (LDN), where the drug is used in doses approximately one-tenth those used for drug/alcohol rehabilitation purposes, is being used by some as an "off-label" experimental treatment for certain immunologically-related disorders,[10] including HIV/AIDS,[11] multiple sclerosis[12] (in particular, the primary progressive variant,[13]) Parkinson's disease, cancer, fibromyalgia,[14] autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and central nervous system disorders.

Sexual dysfunction

Naltrexone can induce early morning erections in patients who suffer from psychogenic erectile dysfunction. The exact pathway of this effect is unknown. Priapism has been reported in two individuals receiving Vivitrol.

Naltrexone has been shown to be effective in the reversal of sexual satiety and exhaustion in male rats.[15]

Tobacco study

The Chicago Stop Smoking Research Project at the University of Chicago studied whether naltrexone could be used as an aid to quit smoking. The researchers discovered that Naltrexone improved smoking cessation rates in women by fifty percent, but showed no improvement for men.[16]

Use for Crohn's disease

In a clinical trial conducted by Pennsylvania State University, it was concluded that low dose naltrexone helped people with Crohn's disease, putting the disease into remission in many cases, though it was stated that further study would be required.[17]

Self-injurious behaviors

Some studies suggest that self-injurious behaviors present in developmentally disabled and autistic people can sometimes be remedied with naltrexone.[18] In these cases, it is believed that the self-injury is being done to release beta-endorphin, which binds to the same receptors as heroin and morphine.[19] By removing the "rush" generated by self-injury, the behavior may stop.

Addiction of heroin

Naltrexone helps patients overcome urges to abuse opiates by blocking the drugs’ euphoric effects. Some patients do well with it, but the oral formulation, the only one available to date, has a drawback: It must be taken daily, and a patient whose craving becomes overwhelming can obtain opiate euphoria simply by skipping a dose before resuming abuse.[20]

Kleptomania

There are indications that naltrexone might be beneficial in the treatment of kleptomania (compulsive stealing).[21]

Study in overweight and obese patients

Participants are being recruited for a study of the effects of Naltrexone therapy in overweight and obese patients.[22]

Autism

Dr. Jaak Panksepp of Washington State University has conducted studies using naltrexone to treat patients with autism. He found that half the autistic children treated with the drug become more social.[23]

References

- ^ Shader, RI. "Antagonists, Inverse Agonists, and Protagonists." Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003 Aug; 23(4):321–322. PMID 12920405

- ^ Therapeutic Goods Administration. "Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods Medicines" (Online database of approved medicines). Retrieved 2009-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink=|title=at position 42 (help) - ^ a b Wodak, Dr. Alex (Summer 07/08). "I woke up cured of Naltrexone!" (Online Version of published magazine article). User's News. New South Wales User's and AIDS Association. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

Maybe there was an increased risk of death when people took naltrexone for a while and then started taking heroin? Maybe the success rate of naltrexone, whether started with UROR or ROD, was not as great as some had claimed?

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hanson, Merideth. "Three". In Alex Gitterman (ed.). The Handbook of Social Work practice with vulnerable and resilient populations, 2nd Edition (Second ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Latt NC, Jurd S, Houseman J, Wutzke SE (2002). "Naltrexone in alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial of effectiveness in a standard clinical setting". Med J Aust. 176 (11): 530–4. PMID 12064984.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Naltrexone or Specialized Alcohol Counseling an Effective Treatment for Alcohol Dependence When Delivered with Medical Management" (Press release). National Institutes of Health. May 2, 2006. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ Sinclair JD (2001). "Evidence about the use of naltrexone and for different ways of using it in the treatment of alcoholism". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 36 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1093/alcalc/36.1.2. PMID 11139409.

- ^ Schmitz J, Stotts A, Rhoades H, Grabowski J (2001). "Naltrexone and relapse prevention treatment for cocaine-dependent patients". Addict Behav. 26 (2): 167–80. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00098-8. PMID 11316375.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anton R, Oroszi G, O’Malley S, Couper D, Swift R, Pettinati H, Goldman D (2008). "An Evaluation of Opioid Receptor (OPRM1) as a Predictor of Naltrexone Response in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (2): 135–144. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.2.135. PMID 18250251.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Low Dose Naltrexone as a preferential mu opiate receptor antagonist in the treatment of various autoimmune diseases. Power Point presentation

- ^ [1]

- ^ LDN for Multiple sclerosis

- ^ Gironi M, Martinelli-Boneschi F, Sacerdote P, Solaro C, Zaffaroni M, Cavarretta R, Moiola L, Bucello S, Radaelli M, Pilato V, Rodegher M, Cursi M, Franchi S, Martinelli V, Nemni R, Comi G, Martino G (2008). "A pilot trial of low-dose naltrexone in primary progressive multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis. 14 (8): 1076–83. doi:10.1177/1352458508095828. PMID 18728058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Addiction Drug May Help Ease Fibromyalgia". 04/16/2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fernández-Guasti A, Rodríguez-Manzo G. Pharmacological and physiological aspects of sexual exhaustion in male rats. Scand J Psychol. 2003 Jul;44(3):257-63. PMID 12914589

- ^ King A, de Wit H, Riley R, Cao D, Niaura R, Hatsukami D (2006). "Efficacy of naltrexone in smoking cessation: A preliminary study and an examination of sex differences". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 8 (5): 671–82. doi:10.1080/14622200600789767.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith J, Stock H, Bingaman S, Mauger D, Rogosnitzky M, Zagon I (2007). "Low-Dose Naltrexone Therapy Improves Active Crohn's Disease". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 102 (4): 820–8. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01045.x. PMID 17222320.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith, Stanley G. (June, 1995). "Effects of naltrexone on self-injury, stereotypy, and social behavior of adults with developmental disabilities". Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 7 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1007/BF02684958.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Manley, Cynthia (1998-03-20). "Self-injuries may have biochemical base: study". The Reporter.

- ^ Naltrexone Appears Safe and Effective for Heroin Addiction

- ^ Grant (2009-04-03). "Drug Suppresses The Compulsion To Steal, Study Shows". Science daily.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|First=ignored (|first=suggested) (help) - ^ url=http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00711477

- ^ Grandin, Temple (2005). Animals in Translation. New York, New York: Scribner. pp. 114–116. ISBN 0743247698.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

Low dose naltrexone

- Low Dose Naltrexone Homepage Research and details on using LDN to treat various diseases.

- 'Those Who Suffer Much Know Much', July 2008; a free book containing 29 low dose naltrexone health success stories presented as case studies, produced by 'Case Health - Health Success Stories' website as a community service.[3]

- LDN Research Trust UK [4]

- AHSTA.com Low-dose Naltrexone in Thyroid Autoimmunity Homepage

- Elaine A. Moore, SammyJo Wilkinson, The Promise of Naltrexone: Potential Benefits of Low Dose Therapy for Patients with Cancer and Neurodegenerative and Autoimmune Disorders Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2008.