Proto-Indo-European mythology

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Template:PIE notice Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and stories associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the hypothetical speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language. Although these stories are not directly attested, they have been reconstructed by scholars of comparative mythology based on the similarities in the belief systems of various Indo-European peoples.

Various schools of thought exist regarding the precise nature of Proto-Indo-European mythology, which do not always agree with each other. The main mythologies used in comparative reconstruction are Vedic, Roman, and Norse, often supported with evidence from the Baltic, Celtic, Greek, Slavic, and Hittite traditions as well.

The Proto-Indo-European pantheon includes well-attested deities such as *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, the god of the daylit skies, his consort *Dʰéǵʰōm, the earth mother, his daughter *Haéusōs, the goddess of the dawn, the divine twins, and the storm god *Perkwunos. Other probable deities include *Péh2usōn, a pastoral god, and *Seh2ul, a female solar deity.

Well-attested myths of the Proto-Indo-Europeans include a myth involving a storm god who slays a multi-headed serpent that dwells in water and a creation story involving two brothers, one of whom sacrifices the other to create the world. The Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed that the Otherworld was guarded by a watchdog and could only be reached by crossing a river. They also may have believed in a world tree, bearing fruit of immortality, either guarded by or gnawed on by a serpent or dragon, and tended by three goddesses who spun the thread of life.

Methods of reconstruction

Schools of thought

The mythology of the Proto-Indo-Europeans is not directly attested and it is difficult to match their language to archaeological findings related to any specific culture from the Chalcolithic.[4] Nonetheless, scholars of comparative mythology have attempted to reconstruct aspects of Proto-Indo-European mythology based on the existence of similarities among the deities, religious practices, and myths of various Indo-European peoples. This method is known as the comparative method. Different schools of thought have approached the subject of Proto-Indo-European mythology from different angles.[5] The Meteorological School holds that Proto-Indo-European mythology was largely centered around deified natural phenomena such as the sky, the Sun, the Moon, and the dawn.[6] This meteorological interpretation was popular among early scholars, such as Friedrich Max Müller, who saw all myths as fundamentally solar allegories.[3] This school lost most of its scholarly support in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[7][6]

The Ritual School, which first became prominent in the late nineteenth century, holds that Proto-Indo-European myths are best understood as stories invented to explain various rituals and religious practices.[8][7] The Ritual School reached the height of its popularity during the early twentieth century.[9] Many of its most prominent early proponents, such as James George Frazer and Jane Ellen Harrison, were classical scholars.[10] Bruce Lincoln, a contemporary member of the Ritual School, argues that the Proto-Indo-Europeans believed that every sacrifice was a reenactment of the original sacrifice performed by the founder of the human race on his twin brother.[8]

The Functionalist School holds that Proto-Indo-European society and, consequently, their mythology, was largely centered around the trifunctional system proposed by Georges Dumézil,[11] which holds that Proto-Indo-European society was divided into three distinct social classes: farmers, warriors, and priests.[11][12][13] The Structuralist School, by contrast, argues that Proto-Indo-European mythology was largely centered around the concept of dualistic opposition.[14] This approach generally tends to focus on cultural universals within the realm of mythology, rather than the genetic origins of those myths,[14] but it also offers refinements of the Dumézilian trifunctional system by highlighting the oppositional elements present within each function, such as the creative and destructive elements both found within the role of the warrior.[14]

Source mythologies

One of the earliest attested and thus most important of all Indo-European mythologies is Vedic mythology,[15] especially the mythology of the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas. Early scholars of comparative mythology such as Friedrich Max Müller stressed the importance of Vedic mythology to such an extent that they practically equated it with Proto-Indo-European myth.[16] Modern researchers have been much more cautious, recognizing that, although Vedic mythology is still central, other mythologies must also be taken into account.[16]

Another of the most important source mythologies for comparative research is Roman mythology.[15][17] Contrary to the frequent erroneous statement made by some authors that "Rome has no myth", the Romans possessed a very complex mythological system, parts of which have been preserved through the characteristic Roman tendency to rationalize their myths into historical accounts.[18] Despite its relatively late attestation, Norse mythology is still considered one of the three most important of the Indo-European mythologies for comparative research,[15] simply due to the vast bulk of surviving Icelandic material.[17]

Baltic mythology has also received a great deal of scholarly attention, but has so far remained frustrating to researchers because the sources are so comparatively late.[19] Nonetheless, Latvian folk songs are seen as a major source of information in the process of reconstructing Proto-Indo-European myth.[20] Despite the popularity of Greek mythology in western culture,[21] Greek mythology is generally seen as having little importance in comparative mythology due to the heavy influence of Pre-Greek and Near Eastern cultures, which overwhelms what little Indo-European material can be extracted from it.[22] Consequently, Greek mythology received minimal scholarly attention until the first decade of the 21st century. [15]

Although Scythians are considered relatively conservative in regards to Proto-Indo-European cultures, retaining a similar lifestyle and culture,[23] their mythology has very rarely been examined in an Indo-European context and infrequently discussed in regards to the nature of the ancestral Indo-European mythology. At least three deities, Tabiti, Papaios and Api, are generally interpreted as having Indo-European origins,[24][25] while the remaining have seen more disparate interpretations. Influence from Siberian, Turkic and even Near Eastern beliefs, on the other hand, are more widely discussed in literature.[26][27][28]

Cosmology

There was a fundamental opposition between the never-ageing gods above in the skies, and the terrestrial and mortal humans beneath on earth.[29] In the Proto-Indo-European worldview very likely existed a superordinate principle of natural order, universal balance and equilibrium that was highest in hierarchy. Linguistically the names of the reflections of this superordinate principle in the various Indo-European cultures can be derived from the PIE form *h2r-tós "properly joined, right, true", from a presumed root *h2er-, cf. the Vedic ऋत ṛta, the Roman Veritas, the Norse Urða, etc. The meaning of the Vedic Ṛta is "fixed or settled order, rule, universal law, fate or truth".[30] All beings in the Proto-Indo-European cosmos are considered to be bound to this superordinate principle: plants, animals, humans, and deities. This highest principle is thought to be the unification of two perfectly balanced complementary principles.[31] This unification of perfectly balanced complementary principles is the root of the balancing and equilibrium aspect of the superordinate principle and it also is reflected in the Proto-Indo-European language; terms that describe opposites are derived from an identical (unifying) root word, i.e. *leuk- ('radiant, light') – *leug- ('dark') ; *yeu- ('to join') – *yeu- ('to separate') *ghos-ti- ('a host') — *ghos-ti- ('a guest').[31][32]

In the Indo-European cosmology, the earth *dhéǵhōm was perceived as a vast, flat and circular continent surrounded by waters ("the Ocean").[33]

Cosmogony

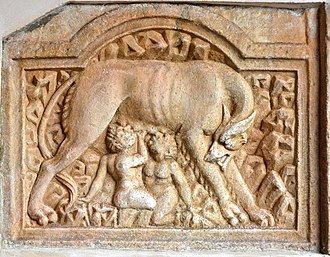

The analysis of different Indo-European tales indicates that the Proto-Indo-Europeans believed there were two progenitors of mankind: *Manu- ("Man") and *Yemo- ("Twin"), his twin brother. A reconstructed creation myth involving the two is given by David W. Anthony, attributed in part to Bruce Lincoln:[34] Manu and Yemo traverse the cosmos, accompanied by the primordial cow, and finally decide to create the world. To do so, Manu sacrifices his twin Yemo (or the cow), and with help from the Sky-Father, the Storm-God and the Divine Twins, forges the earth from Yemo's remains. Manu thus becomes the first priest, initiating both sacrifice and human laws.[35] To the third man, *Trito, the celestial gods then present the cattle, which is stolen by a three-headed serpent named *Ngwhi. Trito eventually overcomes the monster, either alone or aided by the Sky-Father, and gives the recovered cattle to a priest for it to be sacrificed. Trito is now the first warrior and ensures that the cycle of mutual giving between gods and humans may continue.[34] Reflexes of *Manu include Indic Manu, Germanic Mannus; of Yemo, Indic Yama, Avestan Yima, Norse Ymir, possibly Roman Remus (< earlier Old Latin *Yemos).[34]

Ramchandra N. Dandekar proposed that the primeval being *Yemo- is not a twin brother of *Manu-, but instead a two-folded hermaphrodite, a pair of two complementary beings twisted or entwined together. In Norse mythology, the name of the primeval being Ymir translates as twin, double being or hermaphrodite,[36] and it may be the case for the Indian Yama. In this interpretation, the primordial hermaphrodite (or twin) is sacrificed or self-sacrifices, and from its corpse the world emerges.[37] This theory has been contested on the ground that yamá nowhere denotes "hermaphrodite" in the ancient Sanskrit tradition.[38]

In the cosmogonic myths of many Indo-European cultures a Cosmic Egg symbolizes the primordial state from which the universe arises.[39] This pre-state or ground state that is described as a primordial void in that two perfectly balanced, complementary quantities emerge (i.e. fire and ice in Norse mythology or breath as inhaling and exhaling or respectively the double-being in the world egg). The two complementary quantities form a union, subsequently this union is separated what causes the universe, symbolized as the world tree, to come into existence.[31]

The Germanic languages have information about both Ymir and Mannus (reflexes of *Yemo- and *Manu- respectively),[40] but they never appear together in the same myth.[40] Instead, they only occur in myths widely separated by both time and circumstances.[40] In chapter two of his book Germania, which was written in Latin in around 98 A.D., the Roman writer Tacitus claims that Mannus, the son of Tuisto, was the ancestor of the Germanic peoples.[40] This name never recurs anywhere in later Germanic literature,[41] but one proposed meaning of the continental Germanic tribal name Alamanni is "Mannus' own people" ("all-men" being another scholarly etymology).[41]

The early "history" of Rome is widely recognized as a historicized retelling of various old myths.[42] Romulus and Remus are twin brothers from Roman mythology who both have stories in which they are killed.[43] The Roman writer Livy reports that Remus was believed to have been killed by his brother Romulus at the founding of Rome when they entered into a disagreement about which hill to build the city on. Later, Romulus himself is said to have been torn limb-from-limb by a group of senators.[44][a] Both of these myths are widely recognized as historicized remnants of the Proto-Indo-European creation story.[44]

Underworld

Most Indo-European traditions contain some kind of Underworld or Afterlife. It is possible that the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed that, in order to reach the Underworld, one needed to cross a river, guided by an old man (*ĝerhaont-).[45] The Greek tradition of the dead being ferried across the river Styx by Charon is probably a reflex of this belief.[45] The idea of crossing a river to reach the Underworld is also present throughout Celtic mythologies.[46] Several Vedic texts contain references to crossing a river in order to reach the land of the dead and the Latin word tarentum meaning "tomb" originally meant "crossing point."[47] In Norse mythology, Hermóðr must cross a bridge over the river Giöll in order to reach Hel.[48] In Latvian folk songs, the dead must cross a marsh rather than a river.[49] Traditions of placing coins on the bodies of the deceased in order to pay the ferryman are attested in both ancient Greek and early modern Slavic funerary practices.[46] It is also possible that the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed that the Underworld was guarded by some kind of watchdog, similar to the Greek Cerberus, the Hindu Śárvara, or the Norse Garmr.[45][50] The king of the Otherworld may have been Yemo, the sacrificed twin of the creation myth.[45][51]

World tree and serpent

The Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed in some kind of world tree (axis mundi).[52] It is also possible that they may have believed that this tree was either guarded by or under constant attack from some kind of dragon or serpent.[52] In Norse mythology, the cosmic tree Yggdrasil is tended by the three Norns while the dragon Nidhogg gnaws at its roots.[52] In Greek mythology, the tree of the golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides is tended by the three Hesperides and guarded by the hundred-headed dragon Ladon.[53] In Indo-Iranian texts, there is a mythical tree dripping with Soma, the immortal drink of the gods and, in later Pahlavi sources, a malicious lizard is said to lurk at the bottom of it.[52]

Eschatology

Several traditions reveal traces of an Indo-European eschatological myth that describes the end of the world following a cataclysmic battle. The story begins when the major foe, usually coming from a different and inimical paternal line, assumes the position of authority among the host of gods or heroes: Norse Loki, Roman Tarquin, Irish Bres. A new leader then springs up (e.g. Irish Lug, Greek Zeus) and the two forces come together to annihilate each other in a cataclysmic battle.[54]

Pantheon

Linguists are able to reconstruct the names of some deities in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) from many types of sources. Some of the proposed deity names are more readily accepted among scholars than others.[b] According to philologist Martin L. West, "the clearest cases are the cosmic and elemental deities: the Sky-god, his partner Earth, and his twin sons; the Sun, the Sun Maiden, and the Dawn; gods of storm, wind, water, fire; and terrestrial presences such as the Rivers, spring and forest nymphs, and a god of the wild who guards roads and herds".[55]

Even at the archaic stage (4500-4000),[c] when the language did not make yet formal distinctions between masculine and feminine and the beliefs were still animistic, it is likely that each deity was conceived as male or female. Archaic Indo-European had indeed a two-gender system which simply distinguished between animate and inanimate, i.e. between the deified and the common word. For instance, fire as an active principle was *hₓn̩gʷnis (lat. ignis ; Skt Agni), while the inanimate, physical entity was *péh₂ur (Grk pyr ; Eng. fire). Sometimes concepts could also be deified, such as Avestan mazdā ("wisdom"), deified as Ahura Mazdā ("Lord Wisdom").[56]

It is not probable that the Indo-Europeans had a fixed canon of deities or assigned a specific number to them.[57] The term for "a god" was *deiwós ("celestial"), from the root *dyeu, which denoted the bright sky or the light of day. It has numerous reflexes in Hittite sius; Latin deus, divus; Sanskrit Dyaus, deva; Avestan daeva (later, Persian, div); Welsh duw; Irish dia; Lithuanian Dievas; Latvian Dievs.[58][59][60] In contrast, humans were synonymous of "mortals", and associated with the "earthly" (*dʰéǵʰōm), likewise the source of words for "man, human being" in various languages.[61] If the gods were exempt from death and disease, it is because they were nourished by special aliments, usually not available to mortals: in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, "the gods, of course, neither eat nor drink. They become sated by just looking at this nectar", while the Edda tells us that "on wine alone the weapon-lord Odin ever lives", "he needs no food; wine is to him both drink and meat".[62]

Gods had several titles, typically "the celebrated", "the highest", "king", or "shepherd",[63] with the notion that gods had their own idiom and true names, which might be kept secret in some circumstances.[64] In Indo-European traditions, gods are seen as the "dispensers", the "givers of good things" (*déh₃tōr h₁uesuom).[65] Although certain individual deities were charged with the supervision of justice or contracts, in general the Indo-European gods did not have an ethical character. Their immense power, which they could exercise at their pleasure, necessitated rituals, sacrifices and praise songs from humans to ensure the gods would bestow favorable fate to the community.[66] The idea that gods were in control of the nature was translated in the suffix *-nos (feminine -nā), which signified "lord of" and is attested in Greek Ouranos ("lord of rain") and Helena ("mistress of sunlight"), Germanic *Wōðanaz ("lord of frenzy"), Gaulish Epona ("goddess of horses"), Lithuania Perkūnas ("lord of oaks"), and perhaps in Roman Neptunus ("lord of waters"), Volcanus ("lord of fire-glare"), and Silvanus ("lord of woods").[67]

Heavenly deities

Sky Father

The head deity of the Proto-Indo-European pantheon was the god *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr,[68] whose name literally means "Sky Father".[68][69][70] Dyēus was the deified daylight sky.[71] He is, by far, the most well-attested of all the Proto-Indo-European deities.[14][72] His dwelling, the skies, became associated with the "heaven", the seat of the gods, in classic proto-Indo-European. As the gateway to the gods and the father of both the Divine Twins and the goddess of the dawn, Hausos, Dyēus was a prominent deity in the pantheon.[73][74] According to West, he was however likely not their ruler, or the holder of the supreme power like Zeus and Jupiter.[75]

Due to his celestial nature, Dyēus is often described as "all-seeing", or "with wide vision" in Indo-European myths. It is unlikely however that he was in charge of the supervision of justice and righteousness, as it was the case for the Zeus or the Indo-Iranian Mithra–Varuna duo; but he was suited to serve at least as a witness to oaths and treaties.[76]

The Greek god Zeus, the Roman god Jupiter, and the Illyrian god Dei-Pátrous all appear as the head gods of their respective pantheons.[77][70] *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr is also attested in the Rigveda as Dyáus Pitā, a minor ancestor figure mentioned in only a few hymns.[78] The ritual expressions Debess tēvs in Latvian and attas Isanus in Hittite are not exact descendants of the formula *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, but they do preserve its original structure.[14]

Dawn Goddess

*Haéusōs has been reconstructed as the Proto-Indo-European goddess of the dawn.[79][80] In three traditions (Indic, Greek, Baltic), the Dawn is the "daughter of heaven", *Dyḗus. In these three branches plus a fourth (Italic), the reluctant dawn-goddess is chased or beaten from the scene for tarrying.[81][82] An ancient epithet to designate the Dawn appears to have been *Dʰuǵhₐtḗr Diwós, "Sky Daughter".[83] Depicted as opening the gates of Heaven when she appears at the beginning of the day,[84] Hausōs is generally seen as never-ageing or born again each morning.[85] Associated with red or golden cloths, she is often portrayed as dancing.[86]

Twenty-one hymns in the Rigveda are dedicated to the dawn goddess Uṣás[87] and a single passage from the Avesta honors the dawn goddess Ušå.[87] The dawn goddess Eos appears prominently in early Greek poetry and mythology.[87] The Roman dawn goddess Aurora is a reflection of the Greek Eos,[87] but the original Roman dawn goddess may have continued to be worshipped under the cultic title Mater Matuta.[87] The Anglo-Saxons worshipped the goddess Ēostre, who was associated with a festival in spring which later gave its name to a month, which gave its name to the Christian holiday of Easter in English.[87] The name Ôstarmânôth in Old High German has been taken as an indication that a similar goddess was also worshipped in southern Germany.[88] The Lithuanian dawn goddess Aušra was still acknowledged in the sixteenth century.[89]

Sun and Moon

*Seh2ul and *Meh1not are reconstructed as the Proto-Indo-European goddess of the Sun and god of the Moon respectively. *Seh2ul is reconstructed based on the Greek god Helios, the Roman god Sol, the Celtic goddess Sul/Suil, the North Germanic goddess Sól, the Continental Germanic goddess *Sowilō, the Hittite goddess "UTU-liya",[90] the Zoroastrian Hvare-khshaeta[90] and the Vedic god Surya.[91] *Meh1not- is reconstructed based on the Norse god Máni, the Slavic god Myesyats,[90] and the Lithuanian god *Meno, or Mėnuo (Mėnulis).[92] The daily course of *Seh2ul across the sky on a horse-driven chariot is a common motif among Indo-European myths. While it is probably inherited, the motif certainly appeared after the introduction of the wheel in the Pontic-Caspian steppe about 3500 BC, and is therefore a late addition to Proto-Indo-European culture.[81]

Although the sun was personified as an independent, female deity,[83] the Proto-Indo-Europeans also visualized the sun as the "lamp of Dyēus" or the "eye of Dyēus", as seen in various reflexes: "the god’s lamp" in Medes by Euripides, "heaven’s candle" in Beowulf, or "the land of Hatti’s torch", as the Sun-goddess of Arinna is called in a Hittite prayer[93] ; and Helios as the eye of Zeus,[94][95] Hvare-khshaeta as the eye of Ahura Mazda, and the sun as "God's eye" in Romanian folklore.[96] The names of Celtic sun goddesses like Sulis and Grian may also allude to this association: the words for "eye" and "sun" are switched in these languages, hence the name of the goddesses.[97]

Divine Twins

The Horse Twins are a set of twin brothers found throughout nearly every Indo-European pantheon who usually have a name that means 'horse', *h₁éḱwos,[74] although the names are not always cognate, and no Proto-Indo-European name for them can be reconstructed.[74]

In most traditions, the Horse Twins are brothers of the Sun Maiden or Dawn goddess, and the sons of the sky god, *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr.[82][98] The Greek Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux) are the "sons of Zeus"; the Vedic Divó nápātā (Aśvins) are the "sons of Dyaús", the sky-god, the Lithuanian Dievo sūneliai (Ašvieniai) are the "sons of the God" (Dievas); and the Latvian Dieva dēli are likewise the "sons of the God" (Dievs).[99][100]

Represented as young men and the steeds who pull the sun across the sky, the Divine Twins rode horses (sometimes they were depicted as horses themselves) and rescued men from mortal peril in battle or at sea.[101] The Divine Twins are often differentiated: one is represented as a young warrior while the other is seen as a healer or concerned with domestic duties.[74] In most tales where they appear, the Divine Twins rescue the Dawn from a watery peril, a theme that emerged from their role as the solar steeds.[102][103] At night, the horses of the sun returned to the east in a golden boat, where they traversed the sea[d] to bring back the Sun each morning. During the day, they crossed the sky in pursuit of their consort, the morning star.[103]

Other reflexes may be found in the Anglo-Saxon Hengist and Horsa (whose names mean "stallion" and "horse"), the Celtic "Dioskouroi" said by Timaeus to be venerated by Atlantic Celts as a set of horse twins, the Germanic Alcis, a pair of young male brothers worshipped by the Naharvali,[105] or the Welsh Brân and Manawydan.[74] The horse twins could have been based on the morning and evening star (the planet Venus) and they often have stories about them in which they "accompany" the Sun goddess, because of the close orbit of the planet Venus to the sun.[106]

Other propositions

Some scholars have proposed a consort goddess named *Diwōnā or *Diuōneh₂,[107] a spouse of Dyēus with a possible descendant in Zeus's consort Dione. A thematic echo occurs in Indra's wife Indrānī, and both deities display a jealous and quarrelsome disposition under provocation. A second descendant may be found in Dia, a mortal said to unite with Zeus in a Greek myth. The story leads ultimately to the birth of the Centaurs after the mating of Dia's husband Ixion with the phantom of Hera, the spouse of Zeus. The reconstruction is however only attested in those two traditions and therefore not secured.[108][109] The Greek Hera, the Roman Juno, the Germanic Frigg and the Indic Sakti are often depicted as the protectress of marriage and fertility, or the bestowal of the gift of prophecy. James P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams note however that "these functions are much too generic to support the supposition of a distinct PIE 'consort goddess' and many of the 'consorts' probably represent assimilations of earlier goddesses who may have had nothing to do with marriage."[110]

In the cosmological model proposed by Jean Haudry, deities of the diurnal sky could not transgress the night sky, inhabited by its own sets of gods and the spirits of the dead.[111] Although the etymological association is often deemed untenable,[112] some scholars have proposed *Uorunos as the nocturnal sky and benevolent counterpart of Dyēus, with possible cognates in Greek Uranos and Vedic Varuna, from the PIE root *uoru-, "to encompass, cover". *Uorunos may have personified the firmament, or dwelled in the night sky. In both Greek and Vedic poetry, Uranos and Varuna are portrayed as "wide-looking", bounding or seizing their victims, and having or being a heavenly "seat".[107]

Nature deities

The substratum of Proto-Indo-European mythology is animistic.[56][31][113] This native animism is still reflected in the Indo-European daughter cultures,[114][115][116][117] In Norse mythology the Vættir are for instance reflexes of the native animistic nature spirits and deities.[118] Trees have a central position in Indo-European daughter cultures, and are thought to be the abode of tree spirits.[119][120]

Earth Mother

The earth goddess, *Dʰéǵʰōm, is portrayed as the vast and dark house of mortals, in contrast with Dyēus, the bright sky and seat of the immortal gods.[121] She is associated with fertility and growth, but also with death as the final dwelling of the deceased.[122] She was likely the consort of the sky father, *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr.[123][124] The duality is associated with fertility, as the crop grows from her moist soil, nourished by the rain of Dyēus.[125] The Earth is thus portrayed as the giver of good things: she is exhorted to become pregnant in an Old English prayer; and Slavic peasants described Zemlja, Mother Earth, as a prophetess that shall offer favourable harvest to the community.[124][126] The unions of Zeus with Selene and Demeter is likewise associated with fertility and growth in Greek mythology.[126] This pairing is further attested in the Vedic pairing of Dyáus Pitā and Prithvi Mater,[123] the Greek pairing of Ouranos and Gaia,[127][124] the Roman pairing of Jupiter and Tellus Mater from Macrobius's Saturnalia,[123] and the Norse pairing of Odin and Jörð. Although Odin is not a reflex of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, his cult may have subsumed aspects of an earlier chief deity who was.[128] The Earth and Heaven couple is however not at the origin of the other gods, as the Divine Twins and Hausos were probably conceived by Dyēus alone.[104]

Cognates include Žemyna, a Lithuanian goddess celebrated as the bringer of flowers; Zemes Māte ("Mother Earth"), one of the goddesses of death in Latvian mythology; the Slavic Mati Syra Zemlya ("Mother Moist Earth"); and the chthonic deities of the underworld in Greek mythology. The possibilities of a Thracian goddess Zemelā (*gʰem-elā) and a Messapic goddess Damatura (*dʰǵʰem-māter), at the origin of the Greek Semele and Demeter respectively, are less secured.[124][129] The commonest epithets attached to the Earth goddess are *Plethₐ-wih₁ (the "Broad One") , attested in the Vedic Pṛthvī, the Greek Plataia and Gaulish Litavis,[33][130] and *Plethₐ-wih₁ Méhₐtēr ("Mother Broad One"), attested in the Vedic and Old English formulas Pṛthvī Mātā and Fīra Mōdor.[131][124] Other frequent epithets include the "All-Bearing One", the one who bears all things or creatures, and the "mush-nourishing" or the "rich-pastured".[132][121]

Weather deity

*Perkwunos has been reconstructed as the Proto-Indo-European god of lightning and storms. It either meant "the Striker" or "the Lord of Oaks",[133][67] and he was probably represented as holding a hammer or a similar weapon.[81][134] Thunder and lightning had both a destructive and regenerative connotation: a lighting bolt can clove a stone or a tree, but is often accompanied with fructifying rain. This likely explains the strong association between the thunder-god and oaks in some traditions.[81] He is often portrayed in connection with stone and (wooden) mountains, probably because the mountainous forests were his realm.[135] The striking of devils, demons or evildoers by Perkwunos is a motif encountered in the myths surrounding the Lithuanian Perkūnas and the Vedic Parjanya, a possible cognate, but also in the Germanic Thor, a thematic echo of Perkwunos.[136][137]

The deities generally agreed to be cognates stemming from *Perkwunos are confined to the European continent, and he could have been a motif developed later in Western Indo-European traditions. The evidence include the Norse goddess Fjǫrgyn (the mother of Thor), the Lithuanian god Perkūnas, the Slavic god Perúnú, and the Celtic Hercynian (Herkynío) mountains or forests.[137][135][138][139] Perëndi, an Albanian thunder-god (from the root perunŭ attached to *dyeus) is also a possible cognate.[140][137] The evidence could extend to the Vedic tradition if we add the god of rain, thunder and lightning Parjánya, although Sanskrit sound laws rather predict a parkūn(y)a form.[141][142]

Through another root *(s)tenh₂ ("thunder") stems a series of cognates found in the Germanic, Celtic and Roman thunder-gods Thor, Taranis and (Jupiter) Tonans.[143][144] According to Jackson, "they may have arisen as the result of fossilisation of an original epithet or epiclesis", as the Vedic Parjanya is also called stanayitnú- ("Thunderer").[145] The Roman god Mars may be a thematic echo of Perkwunos, since he originally had thunderer characteristics.[146]

Fire deities

Although the etymological evidence is restricted to Vedic and Baltic traditions, scholars have proposed that *Hₓn̩gʷnis represented the fire conceived as a divine entity.[147][148] In the Indian Rigveda, Agni is pictured as the god of both terrestrial and celestial fires. He was "seen from afar" and "untiring", and embodied the fire of the sun and lightning, as well as the forest fire, the domestic hearth fire and the sacrificial altar, thus linking heaven and earth in a ritual dimension.[147] Early modern sources attest that Lithuanian priests worshipped a "holy Fire" named Ugnis szwenta, which they tried to maintain in perpetual life. Uguns māte was also worshipped as the "Mother of Fire" in Latvia, but if tenth-century Persian sources attest the veneration of fire among the Slavs, there is no evidence that it occurred under the Old Church Slavonic name ognĭ.[149] Another cognate may also be found in Enji, an Illyrian god of fire.[150] In other traditions, as the sacral name of the dangerous fire may have become a word taboo in Indo-European languages,[147] the word served instead as an ordinary word for fire, like in Latin ignis.[151]

Scholars generally argue that the cult of the hearth dates back to Proto-Indo-European times. The domestic fire had to be tended with care and given offerings, and if one moved to a new house, one carried fire to the new home from the old one.[149] The Avestan Ātar was the god of the sacral and hearth fire, often personified and honoured as a god.[147] In Albanian beliefs, Nëna e Vatrës ("The Mother of the Hearth") is a mythological being regarded as a supernatural protector of the hearth (vatër).[152][153] Herodotus reported a Scythian goddess of hearth named Tabiti, a term likely given under a slightly distorted guise, as she might represent a feminine participial form corresponding to an Indo-Iranian god named *Tapatī, "the Burning one". The sacral or domestic hearth can likewise be found in the Greek and Roman hearth goddesses Hestia and Vesta, two names that may derive from the PIE root *h₁u-es- ("burning").[147][148] Both the ritual fires set in the temples of Vesta and the domestic fires of ancient India were circular, rather than the square form reserved for public worshipped in India and for the other gods in Roman antiquity.[154] Additionally, the custom that the bride circles the hearth three times is common to Indian, Ossetian, Slavic, Baltic, and German traditions.[149]

Water deities

It is probable that Proto-Indo-European beliefs featured some sorts of beautiful and sometimes dangerous water goddesses who seduced mortal men, akin to the Greek naiads, the nymphs of fresh waters.[155] The Vedic Apsarás are said to frequent forest lakes, rivers, trees, and mountains. They are of outstanding beauty, and Indra sends them to lure men. In Ossetic mythology, the waters are ruled by Donbettyr ("Water-Peter"), who has daughters of extraordinary beauty and with golden hair. In Armenian folklore, the Parik take the form of beautiful women and dance amid nature. The Slavonic water nymphs víly are beautiful maidens with long golden or green hair who like young men and can also do harm if offended.[156] The Albanian mountain nymphs, Perit and Zana, are depicted as beautiful but also dangerous creatures. Similar to the Baltic nymph-like Laumes, they have the habit of abducting children. The beautiful and long-haired Laumes also have sexual relations and short-lived marriages with men. The Breton Korrigans, irresistible creatures with golden hair, woo mortal men and cause them to perish for love.[157] The Norse Huldra, Iranian Ahuraīnīs and Lycian Eliyãna can likewise be regarded as reflexes of the water nymphs.[158]

A wide range of linguistic and cultural evidence attests the holy status of the terrestrial (potable) waters *āp-, venerated collectively as "the Waters" or divided into "Rivers and Springs".[159] The cults of fountains and rivers, which may have preceded Proto-Indo-European beliefs by tens of thousands of years, was also prevalent in their tradition.[160] Some authors have proposed *Neptonos or *H2epom Nepōts as the Proto-Indo-European god of the waters. The name literally means "Grandson [or Nephew] of the Waters".[162][163] Philologists reconstruct his name from that of the Vedic god Apám Nápát, the Roman god Neptūnus, and the Old Irish god Nechtain. Although such a god has been solidly reconstructed in Proto-Indo-Iranian religion, Mallory and Adams nonetheless still reject him as a Proto-Indo-European deity on linguistic grounds.[163]

Wind deities

We find evidence for the deification of the wind in most Indo-European traditions. The root *h₂weh₁ ("to blow") is at the origin of the two words for the wind: *H₂weh₁-yú- and *H₂w(e)h₁-nt-.[164][165] The deity is indeed often depicted as a duo. Vayu-Vāta is a dual divinity in the Avesta, Vāta being associated with the stormy winds and described as coming from everywhere ("from below, from above, from in front, from behind"). Similarly, the Vedic Vāyu, the lord of the winds, is associated in the Vedas with Indra—the king of the highest heaven—while the other deity Vāta represents a more violent sort of wind and is instead associated with Parjanya—the god of rain and thunder.[165] Other cognates include Hitt. huwant-, Lith. vėjas, TochB yente, Lat. uentus, Ger. *windaz, or Welsh gwynt.[165]

Guardian deity

The association between Greek god Pan and Vedic god Pūshān was first identified in 1924 by the German scholar Hermann Collitz.[166][167] Both were worshipped as pastoral deities, which led scholars to reconstruct *Péh2usōn ("Protector") as a pastoral god guarding roads and herds.[168][169] He may have had an unfortunate appearance, a bushy beard and a keen sight.[170][169] He was also closely affiliated with goats or bucks: Pūshān has goats to pull his car and goats were sacrificed to him on occasion while Pan has goat’s legs.[169][171] The minor discrepancies between the two deities could be explained by the possibility that many attributes originally associated with Pan may have been transferred over to his father Hermes.[168][171]

The reflex is at least of Graeco-Aryan origin. According to West, "Pūshān and Pan agree well enough in name and nature—especially when Hermes is seen as a hypostasis of Pan—to make it a reasonable conclusion that they are parallel reflexes of a prototypical god of ways and byways, a guide on the journey, a protector of flocks, a watcher of who and what goes where, one who can scamper up any slope with the ease of a goat."[172]

Other propositions

In 1855, Adalbert Kuhn suggested that the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed in a set of helper deities, whom he reconstructed based on the Germanic elves and the Hindu ribhus.[173] Although this proposal is often mentioned in academic writings, very few scholars actually accept it since the cognate relationship is linguistically difficult to justify.[174][175] While stories of elves, satyrs, goblins and giants show recurrent traits in Indo-European traditions, West notes that "it is difficult to see so coherent an overall pattern as with the nymphs. It is unlikely that the Indo-Europeans had no concept of such creatures, but we cannot define with any sharpness of outline what their conceptions were."[176] A wild god named *Rudlos has also been proposed, based on the Vedic Rudrá and the Old Russian Rŭglŭ. Problematic is whether the name derives from *reud- ("rend, tear apart"; akin to Lat. rullus, "rustic"), or rather from *reu- ("howl").[177]

Although the name of the divinities are not cognates, a horse goddess portrayed as bearing twins and in connection with fertility and marriage has been proposed based on the Gaulish Epona, Irish Macha and Welsh Rhiannon, with other thematic echos in the Greek and Indic traditions.[178][179] Demeter transformed herself into a mare when she is raped by Poseidon appearing as a stallion, and gave birth to a daughter and a horse, Areion. Similarly, the Indic tradition tells of Saranyu fleeing from her husband Vivásvat when she assumed the form of a mare. Vivásvat metamorphosed into a stallion and of their intercourse were born the twin horses Aśvins. The Irish goddess Macha gave birth to twins, a mare and a boy, and the Welsh figure Rhiannon bore a child who was reared along with a horse.[180]

A river goddess *Dehanu- has been proposed based on the Vedic goddess Dānu, the Irish goddess Danu, the Welsh goddess Don and the names of the rivers Danube, Don, Dnieper, and Dniester. Mallory and Adams however note that while the cognate network is probable, there is not evidence of an associated worship outside India.[177] Some have also proposed the reconstruction of a sea god named *Trihatōn based on the Greek god Triton and the Old Irish word trïath, meaning "sea". Mallory and Adams reject this reconstruction as having no basis, asserting that the "lexical correspondence is only just possible and with no evidence of a cognate sea god in Irish."[177]

Societal deities

Fate goddesses

It is highly probable that the Proto-Indo-Europeans believed in three fate goddesses who spun the destinies of mankind.[181] Although such fate goddesses are not directly attested in the Indo-Aryan tradition, the Atharvaveda does contain an allusion comparing fate to a warp.[182] Furthermore, the three Fates appear in nearly every other Indo-European mythology.[182] The earliest attested set of fate goddesses are the Gulses in Hittite mythology, who were said to preside over the individual destinies of human beings.[182] They often appear in mythical narratives alongside the goddesses Papaya and Istustaya,[182] who, in a ritual text for the foundation of a new temple, are described sitting holding mirrors and spindles, spinning the king's thread of life.[182] In the Greek tradition, the Moirai ("Apportioners") are mentioned dispensing destiny in both the Iliad and the Odyssey, in which they are given the epithet Κλῶθες (Klothes, meaning "Spinners").[183][184] In Hesiod's Theogony, the Moirai are said to "give mortal men both good and ill" and their names are listed as Klotho ("Spinner"), Lachesis ("Apportioner"), and Atropos ("Inflexible").[185][186] In his Republic, Plato records that Klotho sings of the past, Lachesis of the present, and Atropos of the future.[187] In Roman legend, the Parcae were three goddesses who presided over the births of children and whose names were Nona ("Ninth"), Decuma ("Tenth"), and Morta ("Death").[186] They too were said to spin destinies, although this may have been due to influence from Greek literature.[186]

In the Old Norse Völuspá and Gylfaginning, the Norns are three cosmic goddesses of fate who are described sitting by the well of Urðr at the foot of the world tree Yggdrasil.[188][189][e] In Old Norse texts, the Norns are frequently conflated with Valkyries, who are sometimes also described as spinning.[189] Old English texts, such as Rhyme Poem 70, and Guthlac 1350 f., reference Wyrd as a singular power that "weaves" destinies.[190] Later texts mention the Wyrds as a group, with Geoffrey Chaucer referring to them as "the Werdys that we clepyn Destiné" in The Legend of Good Women.[191][187][f] A goddess spinning appears in a bracteate from southwest Germany[187] and a relief from Trier shows three mother goddesses, with two of them holding distaffs.[187] Tenth-century German ecclesiastical writings denounce the popular belief in three sisters who determined the course of a man's life at his birth.[187] An Old Irish hymn attests to seven goddesses who were believed to weave the thread of destiny, which demonstrates that these spinster fate-goddesses were present in Celtic mythology as well.[192] A Lithuanian folktale recorded in 1839 recounts that a man's fate is spun at his birth by seven goddesses known as the deivės valdytojos and used to hang a star in the sky;[192] when he dies, his thread snaps and his star falls as a meteor.[192] In Latvian folk songs, a goddess called the Láima is described as weaving a child's fate at its birth.[192] Although she is usually only one goddess, the Láima sometimes appears as three.[192] The three spinning fate goddesses appear in Slavic traditions in the forms of the Russian Rožanicy, the Czech Sudičky, the Bulgarian Narenčnice or Urisnice, the Polish Rodzanice, the Croatian Rodjenice, the Serbian Sudjenice, and the Slovene Rojenice.[193] Albanian folk tales speak of the Fatit, three old women who appear three days after a child is born and determine its fate, using language reminiscent of spinning.[194]

Welfare god

*Aryo-men has been reconstructed as a deity in charge of welfare and the community, connected to the building and maintenance of roads or pathways, but also with healing and the institution of marriage.[195][196] It derives from the root *h₄erós (a "member of one’s own group", "one who belongs to the community in contrast to an outsider"), which would give the Indo-Iranian term árya (an endonym) and the Irish aire ("noble, chief").[197][198] The Vedic god Aryaman is frequently mentioned in the Vedas, and associated with social and marital ties. In the Gāthās, the Iranian god Airyaman seems to denote the wider tribal network or alliance, and is invoked in a prayer against illness, magic, and evil.[196] In the mythical stories of the founding of the Irish nation, the hero Éremón became the first king of the Milesians (the mythical name of the Irish) after he helped conquer the island from the Tuatha Dé Danann. He also provided wives to the Cruithnig (the mythical Celtic Britons or Picts), a reflex of the marital functions of *Aryo-men.[199]

Smith god

Although the name of a particular Proto-Indo-European smith god cannot be linguistically reconstructed,[163] it is highly probable that the Proto-Indo-Europeans had a smith deity of some kind, since smith gods occur in nearly every Indo-European culture, with examples including the Hittite god Hasammili, the Vedic god Tvastr, the Greek god Hephaestus, the Germanic villain Wayland the Smith, and the Ossetian culture figure Kurdalagon.[200] Mallory notes that "deities specifically concerned with particular craft specializations may be expected in any ideological system whose people have achieved an appropriate level of social complexity".[201] Nonetheless, two motifs recurs frequently in Indo-European traditions: the making of the chief god’s distinctive weapon (Indra’s and Zeus’ bolt; Lugh’s spear) by a special artificer, and the craftsman god’s association with the immortals’ drinking.[202] Smith mythical figures share other characteristics in common. Hephaestus, the Greek god of blacksmiths, and Wayland the Smith, a nefarious blacksmith from Germanic mythology, are both described as lame.[203] Additionally, Wayland the Smith and the Greek mythical inventor Daedalus both escape imprisonment on an island by fashioning sets of mechanical wings from feathers and wax and using them to fly away.[204]

Other propositions

The Proto-Indo-Europeans may also have had a goddess who presided over the trifunctional organization of society. Various epithets of the Iranian goddess Anahita and the Roman goddess Juno provide sufficient evidence to solidly attest that she was probably worshipped, but no specific name for her can be lexically reconstructed.[205] Vague remnants of this goddess may also be preserved in the Greek goddess Athena.[206] A decay goddess has also been proposed on the basis of the Vedic Nirṛti and the Roman Lūa Mater.[177]

Michael Estell has reconstructed a mythical craftsman named *H₃rbʰeu based on the Greek Orpheus and the Vedic Ribhus. Both are the son of a cudgel-bearer or an archer, and both are known as "fashioners" (*tetḱ-).[207] A mythical hero named *Promāth₂eu has been also been proposed, based on the Greek Prometheus ("the one who steals"), who took the heavenly fire away to bring it to mankind, and the Vedic Mātariśvan, the mythical bird who "robbed" (mathnati; occasionally found as pra math-, "to steal") the hidden fire and gave it to the Bhrigus.[171][208]

Some scholars have proposed a war god *Māwort- based on the Roman god Mars and the Vedic Marutás, companions of the war-god Indra. Mallory and Adams, however, reject this reconstruction on linguistic grounds.[209] Likewise, some researchers have found it more plausible that Mars was originally a storm deity, while this cannot be said for Ares.[210]

Myths

Serpent-slaying myth

One common myth found in nearly all Indo-European mythologies is a battle ending with a hero or god slaying a serpent or dragon of some sort.[211][212][213] Although the details of the story often vary widely, several features remain remarkably the same in all iterations. The protagonist of the story is usually a thunder-god, or a hero who is somehow associated with thunder.[214] His enemy the serpent is frequently associated with water, and is depicted as multi-headed, or else "multiple" in some other way.[213] Described as a "blocker of waters", the serpent's heads are eventually smashed up by the thunder-god, releasing torrents of water that had previously been pent up.[215] The myth may have symbolized a clash between forces of order and chaos.[216] The dragon or serpent loses in every version of the story, although in some mythologies, such as the Norse Ragnarök myth, the hero or the god dies with his enemy during the epic battle.[217] Bruce Lincoln has proposed that the tale of the dragon-slaying and the creation myth of *Trito killing the serpent *Ngwhi may actually belong to the same tale.[218][219]

Reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European dragon-slaying myth appear in most Indo-European poetic traditions, where the myth has left traces of the formulaic sentence *(h₁e) gʷʰent h₁ógʷʰim ("[he] slew the serpent").[220] In Hittite mythology, the storm god Tarhunt slays the giant serpent Illuyanka.[221] In the Rigveda, the god Indra slays the multi-headed serpent Vritra, which had been causing a drought by trapping the waters in his mountain lair.[215][222] Several variations of the story are also found in Greek mythology as well.[223] The story is attested in the legend of Zeus slaying the hundred-headed Typhon from Hesiod's Theogony,[212][224] but it is also in the myths of the slaying of the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra by Heracles and the slaying of Python by Apollo.[212][225] The story of Heracles's theft of the cattle of Geryon is probably also related.[212] Although Heracles is not usually thought of as a storm deity in the conventional sense, he bears many attributes held by other Indo-European storm deities, including physical strength and a knack for violence and gluttony.[212][226]

The original Proto-Indo-European myth is also reflected in Germanic mythology.[227] In Norse mythology, Thor, the god of thunder, slays the giant serpent Jörmungandr, which lived in the waters surrounding the realm of Midgard.[228][229] Other dragon-slaying myths are also found in the Germanic tradition: in the Völsunga saga, Sigurd slays the dragon Fafnir and, in Beowulf, the eponymous hero slays a different dragon.[230] The depiction of dragons hoarding a treasure (symbolizing the wealth of the community) in Germanic legends may be a reflex of the original myth of the serpent holding waters.[220]

In Zoroastrianism and Persian mythology, Fereydun, and later Garshasp, slays the serpent Zahhak. In Slavic mythology, Perun, the god of storms, slays his enemy the dragon-god Veles, and the bogatyr hero Dobrynya Nikitich slays the three-headed dragon Zmey. In Armenian mythology, the god of thunders Vahagn slays the dragon Vishap,[231] and the knight hero Făt-Frumos slays the fire-spitting monster Zmeu in Romanian folklore. The god of healing Dian Cecht also slays Meichi in Celtic mythology.[216]

Fire in water

Another reconstructed myth is the story of the fire in the waters. It depicts a fiery divine being, *H2epom Nepōts, who dwells in waters and can only be approached by someone especially designated for the task.[232][233]

In the Rigveda, the god Apám Nápát is envisioned as a form of fire residing in the waters.[234][235] In Celtic mythology, a well belonging to the god Nechtain is said to blind all those who gaze into it.[232][236] In an old Armenian poem, a small reed in the middle of the sea spontaneously catches fire and the hero Vahagn springs forth from it with fiery hair and a fiery beard and eyes that blaze as suns.[237] In a ninth-century Norwegian poem by the poet Thiodolf, the name sǣvar niþr, meaning "grandson of the sea," is used as a kenning for fire.[238] Even the Greek tradition contains possible allusions to the myth of a fire-god dwelling deep beneath the sea.[237] The phrase "νέποδες καλῆς Ἁλοσύδνης," meaning "descendants of the beautiful seas," is used in The Odyssey 4.404 as an epithet for the seals of Proteus.[237]

In general the union of complementary principles, like in this case the union of fire and water, appears to be a fundamental and repeating pattern in Proto-Indo-European mythology. Other examples include the hermaphrodite, twin or two-fold primeval being from that the world tree emerges, the marriage (union) of the Sky Father with the Earth Mother, the Dawn goddess that is the personified union of night and day and in general the often complementary character of the triads.[239]

Binding of evil

Jaan Puhvel notes similarities between the Norse myth in which the god Týr inserts his hand into the wolf Fenrir's mouth while the other gods bind him with Gleipnir, only for Fenrir to bite off Týr's hand when he discovers he cannot break his bindings,[240] and the Iranian myth in which Jamshid rescues his brother's corpse from Ahriman's bowels by reaching his hand up Ahriman's anus and pulling out his brother's corpse, only for his hand to become infected with leprosy.[241] In both accounts, an authority figure forces the evil entity into submission by inserting his hand into the being's orifice (in Fenrir's case the mouth, in Ahriman's the anus) and losing it.[241] Fenrir and Ahriman fulfill different roles in their own mythological traditions and are unlikely to be remnants of a Proto-Indo-European "evil god";[242] nonetheless, it is clear that the "binding myth" is of Proto-Indo-European origin.[243]

Rituals

Indo-Europeans religion was centered on sacrificial rites of cattle and horses, probably administered by a class of priests or shamans. Animals were slaughtered (*gʷʰn̥tós) and dedicated to the gods (*déiwos) in the hope of winning their favour.[244] The Khvalynsk culture, associated with archaic Proto-Indo-European, had already shown archeological evidence for the sacrifice of domesticated animal.[245]

Priesthood

The king as the high priest would have been the central figure in establishing favourable relations with the other world.[244] Georges Dumézil suggested that the religious function was represented by a duality, one reflecting the magico-religious nature of priesthood, while the other is involved in religious sanction to human society (especially contracts), a theory supported by common features in Iranian, Roman, Scandinavian and Celtic traditions.[244]

Sacrifices

The reconstructed cosmology of the proto-Indo-Europeans shows that ritual sacrifice of cattle, the cow in particular, was at the root of their beliefs, as the primordial condition of the world order.[246][245] The myth of *Trito, the first warrior, involves the liberation of a cattle stolen by a three-headed named *Ngwhi. After recovering the wealth of the people, Trito eventually offered the cattle to the priest in order to ensure the continuity of the cycle of giving between gods and humans.[218] The creation myth could have rationalised raiding as the recovery of cattle that the gods had intended for the people who sacrificed properly. Many Indo-European cultures preserved the tradition of cattle raiding, which they often associated with epic myths.[246] Proto-Indo-Europeans also had a sacred tradition of horse sacrifice for the renewal of kinship involving the ritual mating of a queen or king with a horse, which was then sacrificed and cut up for distribution to the other participants in the ritual.[247][219] Jaan Puhvel has compared the Gaulish God Epomeduos (the "master of horses")[248] with the Vedic name of the horse sacrifice, aśvamedhá.[249] The word for "oath", *h₁óitos, derives from the verb *h₁ei- ("to go"), after the practice of walking between slaughtered animals as part of taking an oath.[250]

See also

- Interpretatio graeca, the comparison of Greek deities to Germanic, Roman, and Celtic deities

- Neolithic religion

- Proto-Indo-European society

Notes

- ^ One of the original sources for the stories of Romulus and Remus is Livy's History of Rome, vol. 1, parts iv–vii and xvi. This has been published in an Everyman edition, translated by W. M. Roberts, E. P. Dutton & Co., New York 1912.

- ^ In order to present a consistent notation, the reconstructed forms used here are cited from Mallory & Adams 2006. For further explanation of the laryngeals – <h1>, <h2>, and <h3> – see the Laryngeal theory article.

- ^ "Classic" is defined by David W. Anthony as the proto-language spoken after the Anatolian split, and "Archaic" as the common ancestor of all Indo-European languages.[23]

- ^ The northern Black Sea or the Sea of Azov.[104]

- ^ The names of the individual Norns are given as Urðr ("Happened"), Verðandi ("Happening"), and Skuld ("Due"),[187] but M. L. West notes that these names may be the result of classical influence from Plato.[187]

- ^ They also, most famously, appear as the Three Witches in William Shakespeare's Macbeth (c. 1606).[187]

References

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 364-365.

- ^ Telegrin & Mallory 1994, p. 54.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 427–431.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 428.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 428–429.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 15–18.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 15.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 429–430.

- ^ Mythe et Épopée I, II, III, by G. Dumézil, Gallimard, 1995.

- ^ Burkert 1985, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 431.

- ^ a b c d Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 440.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, p. 14.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, p. 191.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 223–228.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 126-127.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 138, 143.

- ^ a b Anthony 2007.

- ^ West 2007.

- ^ Macaulay, G. C. (1904). The History of Herodotus, Vol. I. London: Macmillan & Co. pp. 313–317.

- ^ Jacobson, Esther (1993-01-01). The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia: A Study in the Ecology of Belief. Brill. ISBN 9789004096288.

- ^ Bessonova, S. S. 1983. Religioznïe predstavleniia skifov. Kiev: Naukova dumka

- ^ Hasanov, Zaur. "Argimpasa – Scythian goddess, patroness of shamans: a comparison of historical, archaeological, linguistic and ethnographic data". Bibliotheca Shamanistica.

- ^ West 2007, p. 340.

- ^ Monier-Williams (1976). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b c d York 1993.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 303.

- ^ a b Delamarre 2003, p. 204-205.

- ^ a b c Anthony 2007, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Mallory & Adams, p. 367.

- ^ Sayers, Edna Edith; Bragg, Lois (2004). Oedipus Borealis: The Aberrant Body in Old Icelandic Myth and Saga. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780838640289.

- ^ Dandekar, Ramchandra Narayan (1979). Vedic mythological tracts. Delhi: Ajanta Publications. OCLC 6917651.

- ^ Van Baaren, Theodorus Petrus (1982). Commemorative Figures. Brill. ISBN 9789004067790.

- ^ Leeming, David Adams (2010). Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia, Book 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 144. ISBN 9781598841749.

- ^ a b c d Puhvel 1987, p. 285.

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2007, pp. 63–69.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 144–165.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 286–287.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, pp. 286–290.

- ^ a b c d Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 439.

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 390.

- ^ West 2007, p. 389.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 390–391.

- ^ West 2007, p. 391.

- ^ West 2007, p. 392.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d West 2007, p. 346.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 439-440.

- ^ West 2007, p. 141.

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 135-136, 138-139.

- ^ West 2007, p. 121-122.

- ^ West 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 408

- ^ Indo-European *Deiwos and Related Words by Grace Sturtevant Hopkins (Language Dissertations published by the Linguistic Society of America, Number XII, December 1932)

- ^ West 2007, p. 124.

- ^ West 2007, p. 157.

- ^ West 2007, p. 129.

- ^ West 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Beekes, Robert Stephen Paul (2011). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9789027211859.

- ^ West 2007, p. 130.

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 137.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 409, 431–432.

- ^ Winters 2003, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Burkert 1985, p. 17.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 166–168.

- ^ West 2007, p. 166.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 230–231.

- ^ a b c d e Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 432.

- ^ West 2007, p. 166-168.

- ^ West 2007, p. 171–175.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 198–200.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 409 and 431.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 410, 432.

- ^ West, 2007 & 217-227.

- ^ a b c d Fortson 2004, p. 23.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 230-231.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 427.

- ^ West 2007, p. 222.

- ^ West 2007, p. 219.

- ^ West 2007, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d e f West 2007, p. 217.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 217–218.

- ^ West 2007, p. 218.

- ^ a b c Gamkrelidze & Ivanov 1995, p. 760.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 232.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 385.

- ^ West 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Sick, David (2004-01-01). "Mit(h)ra(s) and the Myths of the Sun". Numen. 51 (4): 432–467. doi:10.1163/1568527042500140. ISSN 1568-5276.

- ^ Bortolani, Ljuba Merlina (2016-10-10). Magical Hymns from Roman Egypt: A Study of Greek and Egyptian Traditions of Divinity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316673270.

- ^ Ionescu, Doina; Dumitrache, Cristiana (2012-01-01). "The Sun Worship with the Romanians". Romanian Astronomical Journal. 22: 155–166.

- ^ MacKillop, James. (1998). Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-280120-1 pp.10, 16, 128

- ^ West 2007, pp. 185–191.

- ^ West 2007, p. 187, 189.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 109.

- ^ West 2007, p. 187-191.

- ^ West 2007, p. 189.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 161.

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 191.

- ^ West 2007, p. 190.

- ^ Michael Shapiro. Journal of Indo-European Studies, 10 (1&2), pp. 137–166; who references D. Ward (1968) "The Divine Twins". Folklore Studies, No. 19. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- ^ a b Jackson 2002, p. 72–74.

- ^ Dunkel, George E. (1988–1990). "Vater Himmels Gattin". Die Sprache. 34: 1–26.

- ^ West 2007, p. 192-193.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 124.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 231.

- ^ Beekes 2009, p. 1128–1129.

- ^ Wolfe, Susan J.; Stanley, Julia Penelope (1980-01-01). "Linguistic problems with patriarchal reconstructions of Indo-European culture: A little more than kin, a little less than kind". Women's Studies International Quarterly. The voices and words of women and men. 3 (2): 227–237. doi:10.1016/S0148-0685(80)92239-3. ISSN 0148-0685.

- ^ Rose, Herbert Jennings (1935). "Nvmen inest: 'Animism' in Greek and Roman Religion". The Harvard Theological Review. 28 (4): 237–257. ISSN 0017-8160.

- ^ Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to The Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press. doi:10.7829/j.ctt1cgf840. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- ^ [1] Dean C. Halverson: Animism: The Religion of the Tribal World, International Journal of Frontier Missions Vol. 15:2, Apr.-June 1998, p. 2 (source shows that an animistic worldview involves belief in natural spirits and deities)

- ^ Stefan Arvidsson: Aryan Idols: Indo-European Mythology as Ideology and Science, University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 136

- ^ Michael Ostling: Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits 'Small Gods' at the Margins of Christendom, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2018

- ^ Stefan Arvidsson: Aryan Idols: Indo-European Mythology as Ideology and Science, University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 136 (last sentences on page)

- ^ Paul Friedrich: Proto-Indo-European trees (1970)

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 178-179.

- ^ West 2007, p. 180-181.

- ^ a b c West 2007, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 174.

- ^ West 2007, p. 180-181, 191.

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 182-183.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 181–183.

- ^ West 2007, p. 183.

- ^ West 2007, p. 174-176.

- ^ West 2007, p. 174–175, 178–179.

- ^ West 2007, p. 174-175, 178-179.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 80-81.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 75–76.

- ^ West 2007, p. 251.

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 241.

- ^ West 2007, p. 240, 244-245.

- ^ a b c Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 582-583.

- ^ Matasović 2009, p. 178.

- ^ Delamarre 2003, p. 165–166.

- ^ West 2007, p. 243.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 410, 433.

- ^ West 2007, p. 245.

- ^ Matasović 2009, p. 384.

- ^ Delamarre 2003, p. 290.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 77.

- ^ York, Michael. Romulus and Remus, Mars and Quirinus. Journal of Indo-European Studies 16:1 & 2 (Spring/Summer, 1988), 153-172.

- ^ a b c d e West 2007, p. 266.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 203.

- ^ a b c West 2007, p. 269.

- ^ Tagliavini, Carlo (1963). Storia di parole pagane e cristiane attraverso i tempi (in Italian). Morcelliana. p. 103.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 122.

- ^ Tirta 2004, p. 410.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 263.

- ^ Fortson 2004, p. 24.

- ^ West 2007, p. 285.

- ^ West 2007, p. 291.

- ^ West 2007, p. 290.

- ^ West 2007, p. 285-288.

- ^ West 2007, p. 274.

- ^ West 2007, p. 279.

- ^ Dumézil, G.(1966). La Religion romaine archaïque, avec un appendice sur la religion des Étrusques. Payot.

- ^ Dumézil, G., [Tr] Krapp, P. (1996). Archaic Roman Religion. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Translation from French by P. Krapp of [161]

- ^ a b c Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 410.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 129.

- ^ a b c West 2007, p. 263-264.

- ^ Beekes 2009, p. 1149.

- ^ H. Collitz, "Wodan, Hermes und Pushan," Festskrift tillägnad Hugo Pipping pȧ hans sextioȧrsdag den 5 November 1924 1924, pp 574–587.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 411 and 434.

- ^ a b c West 2007, p. 282.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Jackson 2002, p. 85.

- ^ West 2007, p. 202-303.

- ^ Kuhn, Adalbert (1855). "Die sprachvergleichung und die urgeschichte der indogermanischen völker". Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung. 4., "Zu diesen ṛbhu, alba.. stellt sich nun aber entschieden das ahd. alp, ags. älf, altn . âlfr"

- ^ Hall, Alaric (2007). Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity (PDF). Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843832942.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ West 2007, p. 297.

- ^ West 2007, p. 303.

- ^ a b c d Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 434.

- ^ O'Brien, Steven (1982). "Dioscuric elements in Celtic and Germanic mythology". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 10: 117–136.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 279.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 280.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 380–385.

- ^ a b c d e West 2007, p. 380.

- ^ Iliad 20.127, 24.209; Odyssey 7.197

- ^ West 2007, pp. 380–381.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, lines 904–906

- ^ a b c West 2007, p. 381.

- ^ a b c d e f g h West 2007, p. 383.

- ^ Völuspá 20; Gylfaginning 15

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 382.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Geoffrey Chaucer, The Legend of Good Women, Hypermnestra 19

- ^ a b c d e West 2007, p. 384.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 384–385.

- ^ West 2007, p. 385.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 375.

- ^ a b West 2007, p. 142.

- ^ Fortson 2004, p. 209.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 266–269.

- ^ West 2007, p. 143.

- ^ West, 2009 & 154–157.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 139.

- ^ West 2009, p. 157.

- ^ West 2009, p. 156.

- ^ West 2009, p. 155.

- ^ Mallory & Adams, p. 433.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 83-84.

- ^ Fortson 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 410–411.

- ^ York, Michael. Romulus and Remus, Mars and Quirinus. Journal of Indo-European Studies 16:1 & 2 (Spring/Summer, 1988), 153-172.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 297–301.

- ^ a b c d e West 2007, pp. 255–259.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 436–437.

- ^ West 2007, pp. 255.

- ^ a b West 2007, pp. 255–257.

- ^ a b Watkins 1995, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 324–330.

- ^ a b Lincoln, Bruce (1976). "The Indo-European Cattle-Raiding Myth". History of Religions. 16 (1): 42–65. doi:10.1086/462755. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 1062296.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 437.

- ^ a b Fortson 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Philo Hendrik Jan Houwink Ten Cate: The Luwian Population Groups of Lycia and Cilicia Aspera During the Hellenistic Period. E. J. Brill, Leiden 1961, pp. 203–220.

- ^ Fortson 2004, p. 26-27.

- ^ West 2007, p. 460.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 448–460.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 460–464.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 374–383.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 414–441.

- ^ West 2007, p. 259.

- ^ Watkins 1995, pp. 429–441.

- ^ Orchard, Andy (2003). A Critical Companion to Beowulf. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 108. ISBN 9781843840299.

- ^ Kurkjian 1958.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 438.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 277–283.

- ^ West 2007, p. 270.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 277–279.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 279.

- ^ a b c West 2007, p. 271.

- ^ West 2007, p. 272.

- ^ Gonda, J. (1960). "Some Observations on Dumézil's Views of Indo-European Mythology". Mnemosyne. 13 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1163/156852560X00011. ISSN 0026-7074. JSTOR 4428321.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 199.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, p. 119.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 452-453.

- ^ a b Anthony 2007, p. 134-35.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 138.

- ^ Fortson 2004, p. 25-26.

- ^ Pinault, Georges-Jean (2007). "Gaulois epomeduos, le maître des chevaux". In Lambert, Pierre-Yves (ed.). Gaulois et celtique continental. Paris: Droz. pp. 291–307. ISBN 978-2-600-01337-6.

- ^ Jackson 2002, p. 94.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 277.

Bibliography

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1400831104

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-32186-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Benveniste, Emile (1973), Indo-European Language and Society, translated by Palmer, Elizabeth, Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami Press, ISBN 978-0-87024-250-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-36281-0

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bernard Sergent. Athéna et la grande déesse indienne, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2008

- Sturluson, Snorri (2006), The Prose Edda, translated by Byock, Jesse, Penguin Classics, p. 164, ISBN 978-0-14-044755-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1984), "Proto-Indo-European Sun Maidens and Gods of the Moon", Mankind Quarterly, 25 (1 & 2): 137–144

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Drinkwater, J. F. (25 January 2007), The Alamanni and Rome 213–496: (Caracalla to Clovis), OUP Oxford, pp. 63–69, ISBN 978-0-19-929568-5

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-0316-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Frazer, James (1919), The Golden Bough, London: MacMillan

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gamkrelidze, Thomas V.; Ivanov, Vjaceslav V. (1995), Winter, Werner (ed.), Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and a Proto-Culture, Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs 80, Berlin: M. De Gruyter

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grimm, Jacob (1966), Teutonic Mythology, translated by Stallybrass, James Steven, London: Dover, (DM)

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jackson, Peter (2002). "Light from Distant Asterisks. Towards a Description of the Indo-European Religious Heritage". Numen. 49 (1): 61–102. ISSN 0029-5973.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Janda, Michael (2005), Elysion. Entstehung und Entwicklung der griechischen Religion, Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen, ISBN 9783851247022

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Janda, Michael (2010), Die Musik nach dem Chaos: der Schöpfungsmythos der europäischen Vorzeit, Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen, ISBN 9783851242270

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lincoln, Bruce (27 August 1991), Death, War, and Sacrifice: Studies in Ideology and Practice, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226482002

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mallory, James P. (1991), In Search of the Indo-Europeans, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q., eds. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5, (EIEC)

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (2006), The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pleins, J. David (2010), When the Great Abyss Opened: Classic and Contemporary Readings of Noah's Flood, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 110, ISBN 978-0-19-973363-7, retrieved 6 April 2017

- Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780190226923.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Puhvel, Jaan (1987), Comparative Mythology, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-3938-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Renfrew, Colin (1987), Archaeology & Language. The Puzzle of the Indo-European Origins, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 978-0-521-35432-5

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shulman, David Dean (1980), Tamil Temple Myths: Sacrifice and Divine Marriage in the South Indian Saiva Tradition, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-5692-3

- Kurkjian, Vahan M., "History of Armenia: Chapter XXXIV", Penelope, University of Chicago, retrieved 6 April 2017

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Telegrin, D. Ya.; Mallory, James P. (1 December 1994), The Anthropomorphic Stelae of the Ukraine: The Early Iconography of the Indo-Europeans, Journal of Indo-European Studies Monograph Series, vol. 11, Washington D.C., United States: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 978-0941694452

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tirta, Mark (2004). Petrit Bezhani (ed.). Mitologjia ndër shqiptarë (in Albanian). Tirana: Mësonjëtorja. ISBN 99927-938-9-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watkins, Calvert (1995), How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-514413-0

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - West, Martin Litchfield (2007), Indo-European Poetry and Myth, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9

- Winter, Werner (2003), Language in Time and Space, Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-017648-3

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - York, Michael (1993-08-01). "Toward a Proto-Indo-European vocabulary of the sacred". WORD. 44 (2): 235–254. doi:10.1080/00437956.1993.11435902. ISSN 0043-7956.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Proto-Indo-European religion

- Proto-Indo-Europeans

- Ancient Greek culture

- Ancient Greek literature

- Ancient Greek religion

- Ancient Roman religion

- Anthropology of religion

- Asian ethnic religion

- Comparative mythology

- European mythology

- Greek mythology

- History of religion

- Indian religions

- Latvian mythology

- Lithuanian mythology

- Neopaganism

- Norse mythology

- Paganism

- Polytheism

- Religion in classical antiquity

- Religion in Greece

- Religious studies

- Roman mythology