Moustache

A moustache (UK: /məˈstɑːʃ/; mustache, US: /ˈmʌstæʃ/)[1] is a growth of facial hair grown above the upper lip and under the nose. Moustaches have been worn in various styles throughout history.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The word "moustache" is French, and is derived from the Italian mustaccio (14th century), dialectal mostaccio (16th century), from Medieval Latin mustacchium (eighth century), Medieval Greek μουστάκιον (moustakion), attested in the ninth century, which ultimately originates as a diminutive of Hellenistic Greek μύσταξ (mustax, mustak-), meaning "upper lip" or "facial hair",[3] probably derived from Hellenistic Greek μύλλον (mullon), "lip".[4][5]

An individual wearing a moustache is said to be "moustached" or "moustachioed" (the latter often referring to a particularly large or bushy moustache).

History

[edit]Research done on this subject has noticed that the prevalence of moustaches and facial hair in general rise and fall according to the saturation of the marriage market.[6] Thus, the density and thickness of the moustache or beard may help to convey androgen levels or age.[7]

Earliest depictions of moustache trace back to Ancient Egypt old kingdom era (ca. 2649–2130 B.C.)

On the right: Hesy-Ra wearing a moustache, 27th century BC

One of the earliest documents of the usage of moustaches (without the beard) can be traced to Iron Age Celts. According to Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian:[8]}}

The Gauls are tall of body with rippling muscles and white of skin and their hair is blond, and not only naturally so for they also make it their practice by artificial means to increase the distinguishing colour which nature has given it. For they are always washing their hair in limewater and they pull it back from the forehead to the nape of the neck, with the result that their appearance is like that of Satyrs and Pans since the treatment of their hair makes it so heavy and coarse that it differs in no respect from the mane of horses. Some of them shave the beard but others let it grow a little; and the nobles shave their cheeks but they let the moustache grow until it covers the mouth.

Moustaches would not go away during the Middle Ages. One prominent example of the moustache in early medieval art is the Sutton Hoo helmet, an elaborately-decorated helmet sporting a faceplate depicting the style on its upper lip. Later on, Welsh leaders and English royalty such as Edward of Wales, would also often wear only a moustache.[9]

Moustache popularity in the west peaked in the 1880s and 1890s coinciding with a popularity in the military virtues of the day.[7]

Various cultures have developed different associations with moustaches. For example, in many 20th-century Arab countries, moustaches are associated with power, beards are associated with Islamic traditionalism, and clean-shaven or lack of facial hair are associated with more liberal, secular tendencies.[10] In Islam, trimming the moustache is considered to be a sunnah and mustahabb, that is, a way of life that is recommended, especially among Sunni Muslims. The moustache is also a religious symbol for the male followers of the Yarsan religion.[11]

Shaving with stone razors was technologically possible from as far back as the Neolithic times. A moustache is depicted on a statue of the 4th Dynasty Egyptian prince Rahotep (c. 2550 BC). Another ancient portrait showing a shaved man with a moustache is an ancient Iranian (Scythian) horseman from 300 BC.

In ancient China, facial hair and the hair on the head were traditionally left untouched because of Confucian influences.[12]

Development and care

[edit]

The moustache forms its own stage in the development of facial hair in adolescent males.[13]

As with most human biological processes, this specific order may vary among some individuals depending on one's genetic heritage or environment.[14][15]

Moustaches can be tended through shaving the hair of the chin and cheeks, preventing it from becoming a full beard. A variety of tools have been developed for the care of moustaches, including safety razors, moustache wax, moustache nets, moustache brushes, moustache combs and moustache scissors.

In the Middle East, there is a growing trend for moustache transplants, which involves undergoing a procedure called follicular unit extraction in order to attain fuller, and more impressive facial hair.[16]

The longest moustache measures 4.29 metres (14.1 ft) and belongs to Ram Singh Chauhan from India. It was measured on the set of the Italian TV show Lo Show dei Record in Rome, Italy, on 4 March 2010.[17]

Styles

[edit]

The World Beard and Moustache Championships 2007 had six sub-categories for moustaches:[18]

- Dalí – narrow, long points bent or curved steeply upward; areas past the corner of the mouth must be shaved. Artificial styling aids needed. Named after Salvador Dalí.

- English moustache – narrow, beginning at the middle of the upper lip the whiskers are very long and pulled to the side, slightly curled; the ends are pointed slightly upward; areas past the corner of the mouth usually shaved. Artificial styling may be needed.

- Freestyle – All moustaches that do not match other classes. The hairs are allowed to start growing from up to a maximum of 1.5 cm beyond the end of the upper lip. Aids are allowed.

- Hungarian – Big and bushy, beginning from the middle of the upper lip and pulled to the side. The hairs are allowed to start growing from up to a maximum of 1.5 cm beyond the end of the upper lip.

- Imperial – whiskers growing from both the upper lip and cheeks, curled upward (distinct from the royale, or impériale)

- Natural – Moustache may be styled without aids.

Other types of moustache include:

- Chevron – covering the area between the nose and the upper lip, out to the edges of the upper lip but no further. Popular in 1970s and 1980s American and British culture. Worn by Ron Jeremy, Richard Petty, Freddie Mercury, Bruce Forsyth and Tom Selleck.

- Fu Manchu – long, downward pointing ends, generally beyond the chin.

- Handlebar – bushy, with small upward pointing ends.

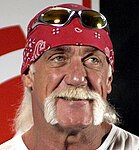

- Horseshoe – Often confused with the Handlebar Moustache, the horseshoe was possibly popularised by modern cowboys and consists of a full moustache with vertical extensions from the corners of the lips down to the jawline and resembling an upside-down horseshoe. Also known as "biker moustache". Worn by Hulk Hogan and Bill Kelliher. Recently re-popularized by Gardner Minshew and Joe Exotic.

- Pancho Villa – similar to the Fu Manchu but thicker; also known as a "droopy moustache". Also similar to the Horseshoe. A Pancho Villa is much longer and bushier than the moustache normally worn by the historical Pancho Villa.

- Pencil moustache – narrow, straight and thin as if drawn on by a pencil, closely clipped, outlining the upper lip, with a wide shaven gap between the nose and moustache. Popular in the 1940s, and particularly associated with Clark Gable. More recently, it has been recognised as the moustache of choice for the fictional character Gomez Addams in the 1990s series of films based on The Addams Family. Also known as a Mouth-brow, and worn by Vincent Price, John Waters, Little Richard, Sean Penn and Chris Cornell.

- Toothbrush – thick, but shaved except for about an inch (2.5 cm) in the centre; worn by Charlie Chaplin, Oliver Hardy, and Adolf Hitler, the latter of whom being responsible for the style becoming extremely unpopular, and remaining so for the nearly-century-long period extending to the present day.

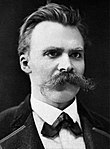

- Walrus – bushy, hanging down over the lips, often entirely covering the mouth. Worn by Mark Twain, David Crosby, Joseph Stalin, John Bolton, Wilford Brimley, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jeff "Skunk" Baxter, Sam Elliott, Albert Einstein, Jamie Hyneman and Robert Johansson .

- Pornstache – A thick, heavy moustache with slightly elongated ends.[19] The style originates among male pornographic actors in the 1970s and was most popular in the 1980s. The pornstache has been worn by celebrities such as Freddie Mercury, Lionel Richie, and Pedro Pascal.[20]

- Moustache styles

-

"Dalí" moustache style

-

"English" moustache style

-

"Fu Manchu" moustache style

-

"Handlebar" moustache style

-

"Horseshoe" moustache style

-

"Imperial " moustache style

-

"Mexican" moustache style

-

"Natural " moustache style

-

"Pencil" moustache style

-

"Toothbrush" moustache style

-

"Walrus" moustache style

-

"Freestyle" moustache style

Occurrence and perceptions

[edit]

Like many other fashion trends, the moustache is subject to shifting popularity through time. Though modern culture often associates moustaches with men of the Victorian era, Susan Walton shows that at the start of the Victorian era facial hair was "viewed with distaste" and that the moustache was considered the mark of an artist or revolutionary, both of which remained on the social fringe at the time.[21] This is supported by the fact that only one Member of Parliament sported facial hair from the years 1841–1847.[21] However, by the 1860s, this had changed and moustaches became wildly popular, even among distinguished men, but by the end of the century, facial hair became passé once more.[21] Though one cannot be entirely sure as to the cause of such changes, Walton speculates that the rise of the facial hair trend was due largely in part to the impending war against Russia, and the belief that moustaches and beards projected a more 'manly' image, which was brought about by the so-called 'rebranding' of the British military and the rehabilitation of military virtues.[21] Moustaches became a defining trait of the British soldier, and until 1916, no enlisted soldier was permitted to shave his upper lip.[22] However, the next generation of men perceived facial hair, such as moustaches, to be an outdated emblem of masculinity and therefore there was a dramatic decline in the moustache trend and a clean-shaven face became the mark of a modern man.[21]

Marriage

[edit]According to a study performed by Nigel Barber, results have shown a strong correlation between a good marriage market for women and an increased number of moustaches worn by the male population.[23] By comparing the number of males pictured in Illustrated London News sporting a moustache against the ratio of single women to single men, the similar trends in the two over the years would suggest that these two factors are correlated.[23] Barber suggests that this correlation may be due to the fact that men with moustaches are perceived to be more attractive, industrious, creative, masculine, dominant and mature by both men and women,[23] as supported by the research conducted by Hellström and Tekle.[24] Barber suggests that these perceived traits would influence a woman's choice of husband as they would suggest likely high reproductive success and other good biological qualities, and a capacity to invest in children, so when males must compete heavily for marriage they are more likely to grow a moustache in an attempt to project these qualities.[23] This theory is also supported by the correlation between beard fashion and women wearing long dresses, as shown by Robinson's study,[25] which then relates to the correlation between dress fashion and the marriage market, as shown in Barber's 1999 study.[26]

Age perception

[edit]The moustache and other forms of facial hair are globally understood to be signs of the post-pubescent male;[27] however, those with moustaches are perceived to be older than those who are clean-shaven of the same age.[27] This was determined by manipulating a photo of six male subjects, with varying levels of baldness, to have moustaches and beards and then asking undergraduate college students to rate both the photos of the men with facial hair and without facial hair in terms of social maturity, aggression, age, appeasement, and attractiveness. Regardless of how bald the subject was, the results found in relation to the perception of moustaches remained constant. Although males with facial hair were perceived, in general, to be older than the same subject pictured without facial hair,[28] the moustached subjects were also perceived to be far less socially mature.[27] The decreased perception of social maturity of the men with moustaches may partially be due to the increase in the perception of aggression in the moustachioed men,[27] as aggression is incompatible with social maturity.[27]

Workplace

[edit]In a study performed by J. A. Reed and E. M. Blunk, persons in management positions were shown to positively perceive, and therefore be more likely to hire, men with facial hair.[29] Although men with beards over all scored better than men with only moustaches, the moustached men scored much higher than those men who were clean-shaven.[29] In this experiment, 228 people, both male and female, who held management positions that made hiring decisions were shown ink sketches of six male job applicants. The men in these ink sketches ranged from clean-shaven, to moustachioed, to bearded. The men with facial hair were rated higher by the employers on aspects of masculinity, maturity, physical attractiveness, dominance, self-confidence, nonconformity, courage, industriousness, enthusiasm, intelligence, sincerity, and general competency.[29] The results were found to be fairly similar for both female and male employers, which Reed and Blunk suggest would imply that gender does not factor into one's perceptions of a moustache on a male applicant.[29] However, Blunk and Reed also stipulate that the meaning and acceptability of facial hair does change depending on the time period. However, the studies performed by Hellström and Tekle,[24] and also the studies performed by Klapprott,[30] would suggest that moustaches are not favourable to all professions as it has been shown that clean-shaven men are seen as more reliable in roles such as salesmen and professors. Other studies have suggested that acceptability of facial hair may vary depending on culture and location, as in a study conducted in Brazil, clean-shaven men were preferred by personnel managers over applicants who were bearded, goateed, or moustached.[31]

Cultures

[edit]In Western culture, it has been shown that women dislike men who displayed a visible moustache or beard, but preferred men who had a visible hint of a beard such as stubble (often known as a five-o-clock shadow) over those who were clean-shaven.[32] This supports the idea that in Western culture, females prefer men who have the capability to cultivate facial hair, such as a moustache, but choose not to. However some researchers have suggested that it is possible that in ecologies in which physical aggressiveness is more adaptive than cooperation, bearded men might be preferred by women.[27] However, varying opinion on moustaches is not reserved to international cultural differences as even within the US, there have been discrepancies observed on female preference of male facial hair as Freedman's study suggested that women studying at the University of Chicago preferred men with facial hair because they perceived them to be more masculine, sophisticated and mature than clean-shaven men.[33] Similarly, a study performed by Kenny and Fletcher at Memphis State University suggested that men with facial hair such as moustaches and beards, were perceived as stronger and more masculine by female students.[34] However, the study performed by Feinman and Gill would suggest that this reaction to facial hair is not nationwide, as women studying in the state of Wyoming showed a marked preference for clean-shaven men over men with facial hair.[35] Some accredit this difference to the difference between region, rurality, and political and social conservatism between the various studies.[35] Thus it can be seen that even within the US, there are slight variations in the perceptions of moustaches.

Religions

[edit]In addition to various cultures, the perception of the moustache is also altered by religion as some religions support the growth of a moustache or facial hair in general, whereas others tend to reject those with moustaches, while many churches remain somewhat ambivalent on the subject.

Amish

[edit]

While Amish men grow beards after marriage and never trim them, they eschew moustaches and continue shaving their upper lips. This is rooted in a rejection of the German military fashion of sporting moustaches, which was prevalent at the time of the Amish community's formation in Switzerland; hence serving as a symbol of their commitment to pacifism.[36]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

[edit]Though it is never explicitly stated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that all male members must be clean-shaven, within Latter-day Saint circles it is often considered "taboo" for men to have moustaches as the missionaries of the church are required to be clean-shaven as well as the honor code of Brigham Young University requiring students to have similar grooming standards. This has become somewhat of a social norm within the church itself.[37] This often leads those members who do choose to wear moustaches feel somewhat like they do not quite fit the norm, and yet in the studies shown done by Nielsen and White, these men reportedly do not mind this feeling and that is why they continue to grow their facial hair.[37]

Islam

[edit]Even though facial grooming is not specifically mentioned within the Qur'an, numerous narrations of hadith (reported sayings of Muhammad) address personal hygiene, including facial hair maintenance.[38] In one such example, Muhammad advised that men must grow beards, and as to moustaches, cut the longer hairs as to not let them cover the upper lips (as this is the Fitra, the tradition of prophets).[39] Thus, growing a beard while keeping the moustache from covering the upper lip is a well-established tradition in many Muslim societies.[38]

Notable moustaches

[edit]Individuals

[edit]The longest moustache measures 4.29 metres (14.1 ft) and belongs to Ram Singh Chauhan of India. It was measured on the set of Lo Show dei Record in Rome, Italy, on 4 March 2010.[17]

In some cases, the moustache is so prominently identified with a single individual that it could identify him without any further identifying traits. For example, Kaiser Wilhelm II's moustache, grossly exaggerated, featured prominently in Triple Entente propaganda. Other notable individuals include: Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Saddam Hussein, Hulk Hogan, Don Frye, Dan Severn, Freddie Mercury, Salvador Dalí, Frank Zappa, Sam Elliott, Tom Selleck, Burt Reynolds, Borat and Steve Harvey. In other cases, such as those of Charlie Chaplin and Groucho Marx, the moustache in question was artificial for most of the wearer's life.

-

Adolf Hitler

-

Joseph Stalin

-

Saddam Hussein

Following a moped accident that left him with a scar on his upper lip, Paul McCartney decided to grow a moustache in order to hide it. The other members of the Beatles decided to do the same. They were first seen with this new look on the cover of their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. This marked the return of young men wearing moustaches in the 1960s.[40]

In art, entertainment, and media

[edit]Alias

[edit]- Moustache was the alias name of a French comic actor, François-Alexandre Galipedes (b. 14 February 1929 in Paris, France – d. 25 March 1987 in Arpajon, Essonne, France), known for his roles in Paris Blues (1961), How to Steal a Million (1966), and Zorro (1975)[41]

Fictional characters

[edit]- Moustaches have long been used by artists to make characters distinctive, as with Charlie Chan, the video game character Mario, Daniel Plainview, Omni-Man, Mike Haggar, Tony Stark, Dr Strange, King Bradley, Saxton Hale, Hercule Poirot, The Lorax, Yosemite Sam or Snidely Whiplash.

- The Bollywood film Sharabi had a character Natthulal whose moustache became a legend. Munchhen hon to Natthulal jaisi, warna na hon (Moustaches should be like Natthulal's or should not be at all) became one of the most quoted pieces of dialogue from the film.

- At least one fictional moustache has been so notable that a whole style has been named after it: the Fu Manchu moustache.

- In the children's series In The Night Garden, Mr. Pontipine has an oversized, black, fake moustache, which covers up his mouth. In the episode titled "Mr. Pontipine's Moustache Flies Away", his fake moustache flew off, but he soon got it back later. https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b00dqz72/in-the-night-garden-series-1-74-mr-pontipines-moustache-flies-away

Literature

[edit]- In 1954, Salvador Dalí published a book dedicated solely to his moustache.[42]

Visual art

[edit]They have also been used to make a social or political point as with:

- Marcel Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), a parody of the Mona Lisa which adds a goatee and moustache

- Frida Kahlo's moustachioed self-portraits

In the military

[edit]

- In the Indian Army, most senior rifle Rajputana regiment soldiers have moustaches,[44][45][46] and the Rajputana Moustache is a symbol of dignity, caste status, and the spirit of Rajput soldiers.[47]

- Moustaches are also noted among U.S. Army armour and cavalry soldiers.[48]

- Moustaches were a compulsory part of the British Army uniform until 1916, and were quite often worn by soldiers later in the Falklands Campaign.

In sport

[edit]- In the early-1970s, Major League Baseball players seldom wore facial hair. As detailed in the book Mustache Gang, Oakland Athletics owner Charlie Finley decided to hold a moustache-growing contest within his team. When the A's faced the Cincinnati Reds, whose team rules forbade facial hair, in the 1972 World Series, the series was dubbed by media as "the hairs vs. the squares".[49]

- For the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing, the Croatia men's national water polo team grew moustaches in honour of coach Ratko Rudić.[50]

- During the 2012 Summer Olympic Games in London Chileans supporters painted moustaches on their skin as a sign of support of gymnast Tomás González.[51] A site called bigoteolimipico.com (olympicmoustache) was created to allow people create Twitter avatars and Facebook images with moustaches in support of González.[52][53]

- NHL player George Parros was so well known for his moustache that replicas were sold by his team, with proceeds going to charity.[54]

- Formula 1 driver Nigel Mansell wore a famous chevron moustache during his racing career. While he shaved it off after his retirement, he did later grow it back.[55]

- NASCAR legend Dale Earnhardt was well known for his moustache.

Gallery

[edit]-

Satirist Michael "Atters" Attree sporting his Handlebar Club tie

-

Venceslau Brás, President of Brazil, with a handlebar or imperial moustache

-

General George Campbell of Inverneill with an imperial moustache

-

Adolf Hitler with a toothbrush moustache

-

Surrealist Salvador Dalí with the flamboyant moustache he popularized

-

Lavishly bemedaled Kaiser Wilhelm II with his distinctive upswept moustache

-

Hulk Hogan with a horseshoe moustache

-

Richard Petty with a chevron moustache (side view)

-

John Waters with a pencil moustache

-

Kyösti Kallio, the 4th President of Finland, with a walrus moustache

-

British Lord Kitchener featured on a WWI recruiting poster

-

Military personnel with moustaches, at the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

See also

[edit]- American Mustache Institute

- Beard

- Bearded lady

- List of facial hairstyles

- Moustache cup

- Movember

- Stache for cash

- Tacheback

References

[edit]- ^ moustache is almost universal in British English while mustache is common in American English, although the third edition of Webster (1961), which gives moustache as the principal headword spelling. Later editions of Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary (from the 1973 eighth edition) give mustache.

- ^ Twickler, Sharon (2018). "Masculinity and the Moustache – Combing Masculine Identity in the Age of the Moustache, 1860–1900". In Evans, Jennifer; Withey, Alun (eds.). New Perspectives on the History of Facial Hair: Framing the Face. Genders and Sexualities in History. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 149–168. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73497-2_8. ISBN 978-3-319-73497-2.

- ^ μύσταξ, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ μύλλον, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ OED s.v. "moustache", "mustachio"; Encyclopædia Britannica Online – Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary

- ^ Barber, Nigel (2001). "Mustache Fashion Covaries with a Good Marriage Market for Women". Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 25 (4): 261–272. doi:10.1023/A:1012515505895. S2CID 59479339.

- ^ a b Oldstone-Moore, Christopher (20 November 2015). "The rise and fall of the military moustache". blog.wellcomelibrary.org. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Diodorus Siculus, Library of History | Exploring Celtic Civilizations".

- ^ Hawksley, Lucinda. "The moustache: A hairy history". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "Syria's assassinated officials and other Arab leaders wear mustaches for the look of power". Slate Magazine. 18 July 2012.

- ^ Safar Faraji, Yarsan. "Another Yarsan follower's mustaches were shaved". majzooban.org.

- ^ Aris Teon (14 March 2016). "Filial Piety (孝) in Chinese Culture".

- ^ "Adolescent Reproductive Health" (PDF). UNESCO Regional Training Seminar on guidance and Counseling. 1 June 2002.

- ^ Chumlea, 1982

- ^ "The No-Hair Scare". PBS. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Surgery offers chance at perfect moustache". 3 News NZ. 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Longest moustache". Guinnessworldrecords.com. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "The World Beard & Moustache Championships". Handlebarclub.co.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "pornstache Meaning & Origin | Slang by Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Seenarine, Neha; Donah, Kaya (22 February 2023). "The pornstache is back in action". The Quinnipiac Chronicle. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Walton, Susan (2008). "From Squalid Impropriety to Manly Respectability: The revival of Beards, Mustaches and Marital Values in the 1850s in England". Nineteenth-Century Contexts. 30 (3): 229–245. doi:10.1080/08905490802347247. S2CID 192036317.

- ^ Skelly, A. R. (1977). The Victorian Army at Home: The Recruitment and Terms and Conditions of the British Regiment, 1859–1899. London: Croom Helm. p. 358.

- ^ a b c d Barber, Nigel (2001). "Mustache Fashion Covaries with a Good Marriage Market for Women". Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 25 (4): 261–272. doi:10.1023/A:1012515505895. S2CID 59479339.

- ^ a b Hellström, Åke; Tekle, Joseph (1997). "Person Perception Through Photographs: Effects of Glasses, Hair, and Beard on Judgements of Occupation and Personal Qualities". European Journal of Social Psychology. 24 (6): 693–705. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420240606.

- ^ Robinson, D. E. (1979). "Fashions in Shaving and Trimming of the Beard: The Men of the Illustrated London News". American Journal of Sociology. 81 (5): 1133–1141. doi:10.1086/226188. S2CID 143710955.

- ^ Barber, Nigel (1999). "Women's Dress Fashion as a Function of Reproductive Strategies". Sex Roles. 40 (5): 459–471. doi:10.1023/A:1018823727012. S2CID 141063809.

- ^ a b c d e f Muscarella, F.; Cunningham, M.R. (1996). "The Evolutionary Significance and Social Perception of Male Pattern Baldness and Facial Hair". Ethology and Sociobiology. 17 (2): 99–117. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(95)00130-1.

- ^ Wogalter, Michael S.; Hosie, Judith A. (1991). "Effects of Cranial and Facial Hair on Perceptions of Age and Person". Journal of Social Psychology. 131 (4): 589–591. doi:10.1080/00224545.1991.9713892. PMID 1943079.

- ^ a b c d Reed, J. Ann; Blunk, Elizabeth M. (1990). "The Influence of Facial Hair on Impression Formation". Social Behavior & Personality. 18 (1): 169–175. doi:10.2224/sbp.1990.18.1.169.

- ^ Klapprott, Jürgen (1979). "Barba Facit Magistrum: An Investigation into the Effect of a Bearded University Teacher on His Students". Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Ihre Anwendungen. 35 (1): 16–27.

- ^ De Souza, Altay Alves Lino; Baião, Ver Baumgarten Ulyssea; Otta, Emma (2003). "Perception of Men's Personal Qualities and Prospect of Employment as a Function of Facial Hair". Psychological Reports. 92 (1): 201–208. doi:10.2466/pr0.2003.92.1.201. PMID 12674283. S2CID 46653382.

- ^ Cunningham, M. R.; Barbee, A. P.; Pike, C. L. (1990). "What do Women Want? Facialmetric Assessment of Multiple Motives in the Perception of Male Facial Physical Attractiveness". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 59 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.1.61. PMID 2213490.

- ^ Freedman, D. (1969). "The Survival Value of the Beard". Psychology Today. 3 (10): 36–39.

- ^ Kenny, Charles T.; Fletcher, Dixie (1973). "Effects of Beardedness on Person Perception". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 37 (2): 413–414. doi:10.2466/pms.1973.37.2.413. PMID 4747356. S2CID 3000160.

- ^ a b Feinman, Saul; Gill, George W. (1977). "Female's Response to Male Beardedness". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 44 (2): 533–534. doi:10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.533. S2CID 144581787.

- ^ "Why Do Amish Men Wear Beards But Not Mustaches?". Curiosity.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ a b Nielsen, Michael E.; White, Daryl (2008). "Men's Grooming in the Latter-day Saints Church: A Qualitative Study of Norm Violation". Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 11 (8): 807–825. doi:10.1080/13674670802087286. S2CID 143033033.

- ^ a b Calcasi, Karen; Gokmen, Mahmut (2011). "The face of Danger: Beards in the U.S. Media's Representation of Arabs, Muslims, and Middle Easterners". Aether: The Journal of Media Geography. 8 (2): 82–96.

- ^ Sahih Bukhari, Book 8, Volume 74, Hadith 312 (Asking Permission).

Narrated Abu Huraira: The Prophet said "Five things are in accordance with the Fitra (i.e. the tradition of prophets): to be circumcised, to shave the pelvic region, to pull out the hair of the armpits, to cut short the moustaches, and to clip the nails.'

- ^ "The accident that made The Beatles grow moustaches". Far Out Magazine. November 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Moustache at IMDb

- ^ Halsman, Philippe; Dalí, Salvador (1954). Dalí's Moustache. A Photographic Interview by Salvador Dalí and Philippe Halsman. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ IANS (3 March 2019). "Beard it like Abhinandan: The moustache trend that signifies heroism". MSN News. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "MOUSTACHE MAKES THE MAN". The Telegraph. 16 July 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Hall, Tarquin (10 July 2012). The Case of the Deadly Butter Chicken: A Vish Puri Mystery. Simon and Schuster. p. 263. ISBN 9781451613186.

- ^ Pipitone, Gianluca (2015). "Documentary Film Festival Archive – Watch Top documentaries online". cultureunplugged.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Kumar, Arjun (23 December 2010). "Chittorgarh: Fortress of courage". The Economic Times. Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Boudrea, Spc. Ian (6 August 2010). "The "Field' Stach": A Commentary". The Official Home Page of the United States Army. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Tiwari, Sanskar (25 August 2018). "Hair vs. Squares: the 1972 Mustache Gang". Beard and Biceps. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Long, Mark (15 August 2008). "Croats pay lip service to team unity". The Boston Globe. NY Times Co. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Hinchas chilenos lucen bigote a lo Toms en Londres". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 5 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "#bigoteolimpico: Ponte el bigote de Tomás González y apóyalo!". Guioteca (in Spanish). Empresa El Mercurio S.A.P. 3 August 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Álvarez, Camila (3 August 2012). "Las redes sociales apoyan a Tomás González usando su característico "bigote olímpico"". BioBioChile (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Hartnett, Sean (5 December 2014). "Celebrated Scrapper George Parros Made The Most of His NHL Life". XN Sports. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "The Top 10 Moustaches in Motorsport: A November Special". Demon Tweeks. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2019.