Electronic music: Difference between revisions

Jerome Kohl (talk | contribs) revert addition of band name (if this one band belongs here, then so do a thousand others) |

→Rise of popular electronic music: added electropop |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 205: | Line 205: | ||

====Rise of popular electronic music==== |

====Rise of popular electronic music==== |

||

{{See also|Progressive rock|Berlin School of electronic music|Krautrock|Space rock|Synthpop}} |

{{See also|Progressive rock|Berlin School of electronic music|Krautrock|Space rock|Electropop|Synthpop}} |

||

In 1979, UK recording artist [[Gary Numan]] helped to bring electronic music into the wider marketplace of pop music with his hit "[[Cars (song)|Cars]]" from the album ''The Pleasure Principle''. Other successful hit electronic singles in the early 1980s included "Just Can't Get Enough" by [[Depeche Mode]], "Don't You Want Me" by [[The Human League]], "Whip It!" by [[Devo]], and finally 1983's "[[Blue Monday (New Order song)|Blue Monday]]" by [[New Order]], which became the best-selling 12-inch single of all time.<ref>[{{Allmusic|class=song|id=t1003217|pure_url=yes}} Bush 2009].</ref> |

The late 1970s saw the emergence of [[electropop]] music, developed by [[Kraftwerk]] of Germany and [[Yellow Magic Orchestra]] of Japan.<ref>{{allmusic|id=/yellow-magic-orchestra-p5886|name=Yellow Magic Orchestra}}</ref> In 1979, UK recording artist [[Gary Numan]] helped to bring electronic music into the wider marketplace of pop music with his hit "[[Cars (song)|Cars]]" from the album ''The Pleasure Principle''. Other successful hit electronic singles in the early 1980s included "Just Can't Get Enough" by [[Depeche Mode]], "Don't You Want Me" by [[The Human League]], "Whip It!" by [[Devo]], and finally 1983's "[[Blue Monday (New Order song)|Blue Monday]]" by [[New Order]], which became the best-selling 12-inch single of all time.<ref>[{{Allmusic|class=song|id=t1003217|pure_url=yes}} Bush 2009].</ref> |

||

====Birth of MIDI==== |

====Birth of MIDI==== |

||

Revision as of 15:53, 25 May 2011

Electronic music is music that employs electronic musical instruments and electronic music technology in its production.[1] In general a distinction can be made between sound produced using electromechanical means and that produced using electronic technology.[2] Examples of electromechanical sound producing devices include the telharmonium, Hammond organ, and the electric guitar. Purely electronic sound production can be achieved using devices such as the Theremin, sound synthesizer, and computer.[3]

Electronic music was once associated almost exclusively with Western art music but from the late 1960s on the availability of affordable music technology meant that music produced using electronic means became increasingly common in the popular domain.[4] Today electronic music includes many varieties and ranges from experimental art music to popular forms such as electronic dance music.

Origins: late 19th century to early 20th century

The ability to record sounds is often connected to the production of electronic music, but not absolutely necessary for it. The earliest known sound recording device was the phonautograph, patented in 1857 by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. It could record sounds visually, but was not meant to play them back.[5]

In 1878, Thomas A. Edison patented the phonograph, which used cylinders similar to Scott's device. Although cylinders continued in use for some time, Emile Berliner developed the disc phonograph in 1887.[6] A significant invention, which was later to have a profound effect on electronic music, was Lee DeForest's triode audion. This was the first thermionic valve, or vacuum tube, invented in 1906, which led to the generation and amplification of electrical signals, radio broadcasting, and electronic computation, amongst other things.

Before electronic music, there was a growing desire for composers to use emerging technologies for musical purposes. Several instruments were created that employed electromechanical designs and they paved the way for the later emergence of electronic instruments. An electromechanical instrument called the Telharmonium (sometimes Teleharmonium or Dynamophone) was developed by Thaddeus Cahill in the years 1898-1912. However, simple inconvenience hindered the adoption of the Telharmonium, due to its immense size. The first electronic instrument is often viewed to be the Theremin, invented by Professor Léon Theremin circa 1919–1920.[7] Other early electronic instruments include the Croix Sonore, invented in 1926 by Nikolai Obukhov, and the Ondes Martenot, which was most famously used in the Turangalîla-Symphonie by Olivier Messiaen as well as other works by him. The Ondes Martenot was also used by other, primarily French, composers such as Andre Jolivet.[8]

Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music

In 1907, just a year later after the invention of the triode audion, Ferruccio Busoni published Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music, which discussed the use of electrical and other new sound sources in future music. He wrote of the future of microtonal scales in music, made possible by Cahill's Dynamophone: "Only a long and careful series of experiments, and a continued training of the ear, can render this unfamiliar material approachable and plastic for the coming generation, and for Art."[9]

Also in the Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music, Busoni states:

Music as an art, our so-called occidental music, is hardly four hundred years old; its state is one of development, perhaps the very first stage of a development beyond present conception, and we—we talk of "classics" and "hallowed traditions"! And we have talked of them for a long time!

We have formulated rules, stated principles, laid down laws;—we apply laws made for maturity to a child that knows nothing of responsibility!

Young as it is, this child, we already recognize that it possesses one radiant attribute which signalizes it beyond all its elder sisters. And the lawgivers will not see this marvelous attribute, lest their laws should be thrown to the winds. This child—it floats on air! It touches not the earth with its feet. It knows no law of gravitation. It is well nigh incorporeal. Its material is transparent. It is sonorous air. It is almost Nature herself. It is—free!

But freedom is something that mankind have never wholly comprehended, never realized to the full. They can neither recognize or acknowledge it.

They disavow the mission of this child; they hang weights upon it. This buoyant creature must walk decently, like anybody else. It may scarcely be allowed to leap—when it were its joy to follow the line of the rainbow, and to break sunbeams with the clouds.[10]

Through this writing, as well as personal contact, Busoni had a profound effect on many musicians and composers, perhaps most notably on his pupil, Edgard Varèse, who said:

Together we used to discuss what direction the music of the future would, or rather, should take and could not take as long as the straitjacket of the tempered system. He deplored that his own keyboard instrument had conditioned our ears to accept only an infinitesimal part of the infinite gradations of sounds in nature. He was very much interested in the electrical instruments we began to hear about, and I remember particularly one he had read of called the Dynamophone. All through his writings one finds over and over again predictions about the music of the future which have since come true. In fact, there is hardly a development that he did not foresee, as for instance in this extraordinary prophecy: 'I almost think that in the new great music, machines will also be necessary and will be assigned a share in it. Perhaps industry, too, will bring forth her share in the artistic ascent.[11]

Futurists

In Italy, the Futurists approached the changing musical aesthetic from a different angle. A major thrust of the Futurist philosophy was to value "noise," and to place artistic and expressive value on sounds that had previously not been considered even remotely musical. Balilla Pratella's "Technical Manifesto of Futurist Music" (1911) states that their credo is: "To present the musical soul of the masses, of the great factories, of the railways, of the transatlantic liners, of the battleships, of the automobiles and airplanes. To add to the great central themes of the musical poem the domain of the machine and the victorious kingdom of Electricity."[12]

On 11 March 1913, futurist Luigi Russolo published his manifesto "The Art of Noises". In 1914, he held the first "art-of-noises" concert in Milan on April 21. This used his Intonarumori, described by Russolo as "acoustical noise-instruments, whose sounds (howls, roars, shuffles, gurgles, etc.) were hand-activated and projected by horns and megaphones."[13] In June, similar concerts were held in Paris.

The 1920–1930s

This decade brought a wealth of early electronic instruments and the first compositions for electronic instruments. The first instrument, the Etherophone, was created by Léon Theremin (born Lev Termen) between 1919 and 1920 in Leningrad, though it was eventually renamed the Theremin. This led to the first compositions for electronic instruments, as opposed to noisemakers and re-purposed machines. In 1929, Joseph Schillinger composed First Airphonic Suite for Theremin and Orchestra, premièred with the Cleveland Orchestra with Leon Theremin as soloist.

In addition to the Theremin, the Ondes Martenot was invented in 1928 by Maurice Martenot, who debuted it in Paris.[14]

The following year, Antheil first composed for mechanical devices, electrical noisemakers, motors and amplifiers in his unfinished opera, Mr. Bloom.

Recording of sounds made a leap in 1927, when American inventor J. A. O'Neill developed a recording device that used magnetically coated ribbon. However, this was a commercial failure. Two years later, Laurens Hammond established his company for the manufacture of electronic instruments. He went on to produce the Hammond organ, which was based on the principles of the Telharmonium, along with other developments including early reverberation units.[15] Hammond (along with John Hanert and C. N. Williams) would also go onto invent another electronic instrument, the Novachord, which Hammond's company manufactured from 1939–1942.[16]

The method of photo-optic sound recording used in cinematography made it possible to obtain a visible image of a sound wave, as well as to realize the opposite goal—synthesizing a sound from an artificially drawn sound wave.

In this same period, experiments began with sound art, early practitioners of which include Tristan Tzara, Kurt Schwitters, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and others.

Development: 1945 to 1960

Musique concrète

Low-fidelity magnetic wire recorders had been in use since around 1900[17] and in the early 1930s the movie industry began to convert to the new optical sound-on-film recording systems based on the photoelectric cell.[18] It was around this time that the German electronics company AEG developed the first practical audio tape recorder, the "Magnetophon" K-1, which was unveiled at the Berlin Radio Show in August 1935.[19]

During World War II, Walter Weber rediscovered and applied the AC biasing technique, which dramatically improved the fidelity of magnetic recording by adding an inaudible high-frequency tone. It extended the 1941 'K4' Magnetophone frequency curve to 10 kHz and improved the signal-to-noise ratio up to 60 dB,[20] surpassing all known recording systems at that time.[21]

As early as 1942 AEG was making test recordings in stereo.[22] However these devices and techniques remained a secret outside Germany until the end of WWII, when captured Magnetophon recorders and reels of Farben ferric-oxide recording tape were brought back to the United States by Jack Mullin and others.[23] These captured recorders and tapes were the basis for the development of America's first commercially-made professional tape recorder, the Model 200, manufactured by the American Ampex company[24] with support from entertainer Bing Crosby, who became one of the first performers to record radio broadcasts and studio master recordings on tape.[25]

Magnetic audio tape opened up a vast new range of sonic possibilities to musicians, composers, producers and engineers. Audio tape was relatively cheap and very reliable, and its fidelity of reproduction was better than any audio medium to date. Most importantly, unlike discs, it offered the same plasticity of use as film. Tape can be slowed down, sped up or even run backwards during recording or playback, with often startling effect. It can be physically edited in much the same way as film, allowing for unwanted sections of a recording to be seamlessly removed or replaced; likewise, segments of tape from other sources can be edited in. Tape can also be joined to form endless loops that continually play repeated patterns of pre-recorded material. Audio amplification and mixing equipment further expanded tape's capabilities as a production medium, allowing multiple pre-taped recordings (and/or live sounds, speech or music) to be mixed together and simultaneously recorded onto another tape with relatively little loss of fidelity. Another unforeseen windfall was that tape recorders can be relatively easily modified to become echo machines that produce complex, controllable, high-quality echo and reverberation effects (most of which would be practically impossible to achieve by mechanical means).

It wasn't long before composers began using the tape recorder to develop a new technique for composition called Musique concrète. This technique involved editing together recorded fragments of natural and industrial sounds.[26] The first pieces of musique concrète were assembled by Pierre Schaeffer, who went on to collaborate with Pierre Henry.

On 5 October 1948, Radiodiffusion Française (RDF) broadcast composer Pierre Schaeffer's Etude aux chemins de fer. This was the first "movement" of Cinq études de bruits, and marked the beginning of studio realizations [27] and musique concrète (or acousmatic art). Schaeffer employed a disk-cutting lathe, four turntables, a four-channel mixer, filters, an echo chamber, and a mobile recording unit.

Not long after this, Henry began collaborating with Schaeffer, a partnership that would have profound and lasting effects on the direction of electronic music. Another associate of Schaeffer, Edgard Varèse, began work on Déserts, a work for chamber orchestra and tape. The tape parts were created at Pierre Schaeffer's studio, and were later revised at Columbia University.

In 1950, Schaeffer gave the first public (non-broadcast) concert of musique concrète at the Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris. "Schaeffer used a PA system, several turntables, and mixers. The performance did not go well, as creating live montages with turntables had never been done before."[28] Later that same year, Pierre Henry collaborated with Schaeffer on Symphonie pour un homme seul (1950) the first major work of musique concrete. In Paris in 1951, in what was to become an important worldwide trend, RTF established the first studio for the production of electronic music. Also in 1951, Schaeffer and Henry produced an opera, Orpheus, for concrete sounds and voices.

Elektronische Musik

Karlheinz Stockhausen worked briefly in Schaeffer's studio in 1952, and afterward for many years at the WDR Cologne's Studio for Electronic Music.

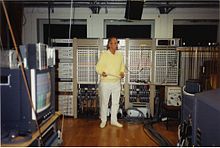

In Cologne, what would become the most famous electronic music studio in the world was officially opened at the radio studios of the NWDR in 1953, though it had been in the planning stages as early as 1950 and early compositions were made and broadcast in 1951.[29] The brain child of Werner Meyer-Eppler, Robert Beyer, and Herbert Eimert (who became its first director), the studio was soon joined by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig. In his 1949 thesis Elektronische Klangerzeugung: Elektronische Musik und Synthetische Sprache, Meyer-Eppler conceived the idea to synthesize music entirely from electronically produced signals; in this way, elektronische Musik was sharply differentiated from French musique concrète, which used sounds recorded from acoustical sources.[30]

With Stockhausen and Mauricio Kagel in residence, it became a year-round hive of charismatic avante-gardism [sic]"[31] on two occasions combining electronically generated sounds with relatively conventional orchestras—in Mixtur (1964) and Hymnen, dritte Region mit Orchester (1967).[32] Stockhausen stated that his listeners had told him his electronic music gave them an experience of "outer space," sensations of flying, or being in a "fantastic dream world"[33] More recently, Stockhausen turned to producing electronic music in his own studio in Kürten, his last work in the genre being Cosmic Pulses (2007).

American electronic music

In the United States, sounds were being created electronically and used in composition, as exemplified in a piece by Morton Feldman called Marginal Intersection. This piece is scored for winds, brass, percussion, strings, 2 oscillators, and sound effects of riveting, and the score uses Feldman's graph notation.

The Music for Magnetic Tape Project was formed by members of the New York School (John Cage, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff, David Tudor, and Morton Feldman),[34] and lasted three years until 1954. Cage wrote of this collaboration: "In this social darkness, therefore, the work of Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff continues to present a brilliant light, for the reason that at the several points of notation, performance, and audition, action is provocative.[35]

Cage completed Williams Mix in 1953 while working with the Music for Magnetic Tape Project.[36] The group had no permanent facility, and had to rely on borrowed time in commercial sound studios, including the studio of Louis and Bebe Barron.

Columbia-Princeton

In the same year Columbia University purchased its first tape recorder—a professional Ampex machine—for the purpose of recording concerts.

Vladimir Ussachevsky, who was on the music faculty of Columbia University, was placed in charge of the device, and almost immediately began experimenting with it.

Herbert Russcol writes: "Soon he was intrigued with the new sonorities he could achieve by recording musical instruments and then superimposing them on one another."[37]

Ussachevsky said later: "I suddenly realized that the tape recorder could be treated as an instrument of sound transformation."[37]

On Thursday, May 8, 1952, Ussachevsky presented several demonstrations of tape music/effects that he created at his Composers Forum, in the McMillin Theatre at Columbia University. These included Transposition, Reverberation, Experiment, Composition, and Underwater Valse. In an interview, he stated: "I presented a few examples of my discovery in a public concert in New York together with other compositions I had written for conventional instruments."[37] Otto Luening, who had attended this concert, remarked: "The equipment at his disposal consisted of an Ampex tape recorder . . . and a simple box-like device designed by the brilliant young engineer, Peter Mauzey, to create feedback, a form of mechanical reverberation. Other equipment was borrowed or purchased with personal funds."[38]

Just three months later, in August 1952, Ussachevsky traveled to Bennington, Vermont at Luening's invitation to present his experiments. There, the two collaborated on various pieces. Luening described the event: "Equipped with earphones and a flute, I began developing my first tape-recorder composition. Both of us were fluent improvisors and the medium fired our imaginations."[38] They played some early pieces informally at a party, where "a number of composers almost solemnly congratulated us saying, 'This is it' ('it' meaning the music of the future)."[38]

Word quickly reached New York City. Oliver Daniel telephoned and invited the pair to "produce a group of short compositions for the October concert sponsored by the American Composers Alliance and Broadcast Music, Inc., under the direction of Leopold Stokowski at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. After some hesitation, we agreed. . . . Henry Cowell placed his home and studio in Woodstock, New York, at our disposal. With the borrowed equipment in the back of Ussachevsky's car, we left Bennington for Woodstock and stayed two weeks. . . . In late September, 1952, the travelling laboratory reached Ussachevsky's living room in New York, where we eventually completed the compositions."[38]

Two months later, on October 28, Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening presented the first Tape Music concert in the United States. The concert included Luening's Fantasy in Space (1952)—"an impressionistic virtuoso piece"[38] using manipulated recordings of flute—and Low Speed (1952), an "exotic composition that took the flute far below its natural range."[38] Both pieces were created at the home of Henry Cowell in Woodstock, NY. After several concerts caused a sensation in New York City, Ussachevsky and Luening were invited onto a live broadcast of NBC's Today Show to do an interview demonstration—the first televised electroacoustic performance. Luening described the event: "I improvised some [flute] sequences for the tape recorder. Ussachevsky then and there put them through electronic transformations."[39]

1954 saw the advent of what would now be considered authentic electric plus acoustic compositions—acoustic instrumentation augmented/accompanied by recordings of manipulated and/or electronically generated sound. Three major works were premiered that year: Varèse's Déserts, for chamber ensemble and tape sounds, and two works by Luening and Ussachevsky: Rhapsodic Variations for the Louisville Symphony and A Poem in Cycles and Bells, both for orchestra and tape. Because he had been working at Schaeffer's studio, the tape part for Varèse's work contains much more concrete sounds than electronic. "A group made up of wind instruments, percussion and piano alternates with mutated sounds of factory noises and ship sirens and motors, coming from two loudspeakers."[40]

Déserts was premiered in Paris in the first stereo broadcast on French Radio. At the German premiere in Hamburg, which was conducted by Bruno Maderna, the tape controls were operated by Karlheinz Stockhausen.[40] The title Déserts, suggested to Varèse not only, "all physical deserts (of sand, sea, snow, of outer space, of empty streets), but also the deserts in the mind of man; not only those stripped aspects of nature that suggest bareness, aloofness, timelessness, but also that remote inner space no telescope can reach, where man is alone, a world of mystery and essential loneliness."[41]

Stochastic music

An important new development was the advent of computers for the purpose of composing music, as opposed to manipulating or creating sounds. Iannis Xenakis began what is called "musique stochastique," or "stochastic music", which is a method of composing that employs mathematical probability systems.[citation needed] Different probability algorithms were used to create a piece under a set of parameters. Xenakis used graph paper and a ruler to aid in calculating the velocity trajectories of glissandi for his orchestral composition Metastasis (1953–54), but later turned to the use of computers to compose pieces like ST/4 for string quartet and ST/48 for orchestra (both 1962).[citation needed]

Mid to late 1950s

In 1954, Stockhausen composed his Elektronische Studie II—the first electronic piece to be published as a score.

In 1955, more experimental and electronic studios began to appear. Notable were the creation of the Studio de Fonologia (already mentioned), a studio at the NHK in Tokyo founded by Toshiro Mayuzumi, and the Phillips studio at Eindhoven, the Netherlands, which moved to the University of Utrecht as the Institute of Sonology in 1960.

The score for Forbidden Planet, by Louis and Bebe Barron,[42] was entirely composed using custom built electronic circuits and tape recorders in 1956.

The world's first computer to play music was CSIRAC which was designed and built by Trevor Pearcey and Maston Beard. Mathematician Geoff Hill programmed the CSIRAC to play popular musical melodies from the very early 1950s. In 1951 it publicly played the Colonel Bogey March of which no known recordings exist.[43] However, CSIRAC played standard repertoire and was not used to extend musical thinking or composition practice which is current computer music practice. CSIRAC was never recorded, but the music played was accurately reconstructed (reference 12). The oldest known recordings of computer generated music were played by the Ferranti Mark 1 computer, a commercial version of the Baby Machine from the University of Manchester in the autumn of 1951. The music program was written by Christopher Strachey.

The impact of computers continued in 1956. Lejaren Hiller and Leonard Isaacson composed Iliac Suite for string quartet, the first complete work of computer-assisted composition using algorithmic composition. "... Hiller postulated that a computer could be taught the rules of a particular style and then called on to compose accordingly."[44] Later developments included the work of Max Mathews at Bell Laboratories, who developed the influential MUSIC I program. Vocoder technology was also a major development in this early era.

In 1956, Stockhausen composed Gesang der Jünglinge, the first major work of the Cologne studio, based on a text from the Book of Daniel. An important technological development of that year was the invention of the Clavivox synthesizer by Raymond Scott with subassembly by Robert Moog.

In 1957, MUSIC, one of the first computer programs to play electronic music, was created by Max Mathews at Bell Laboratories.

Also in 1957, Kid Baltan (Dick Raaymakers) and Tom Dissevelt released their debut album, Song Of The Second Moon, recorded at the Phillips studio.[45]

The public remained interested in the new sounds being created around the world, as can be deduced by the inclusion of Varèse's Poème électronique, which was played over four hundred loudspeakers at the Phillips Pavilion of the 1958 Brussels World Fair. That same year, Mauricio Kagel, an Argentine composer, composed Transición II. The work was realized at the WDR studio in Cologne. Two musicians perform on a piano, one in the traditional manner, the other playing on the strings, frame, and case. Two other performers use tape to unite the presentation of live sounds with the future of prerecorded materials from later on and its past of recordings made earlier in the performance.

Expansion: 1960s

These were fertile years for electronic music—not just for academia, but for independent artists as synthesizer technology became more accessible. By this time, a strong community of composers and musicians working with new sounds and instruments was established and growing. 1960 witnessed the composition of Luening's Gargoyles for violin and tape as well as the premiere of Stockhausen's Kontakte for electronic sounds, piano, and percussion. This piece existed in two versions—one for 4-channel tape, and the other for tape with human performers. "In Kontakte, Stockhausen abandoned traditional musical form based on linear development and dramatic climax. This new approach, which he termed 'moment form,' resembles the 'cinematic splice' techniques in early twentieth century film."[46]

The first of these synthesizers to appear was the Buchla. Appearing in 1963, it was the product of an effort spearheaded by musique concrète composer Morton Subotnick.

The theremin had been in use since the 1920s but it attained a degree of popular recognition through its use in science-fiction film soundtrack music in the 1950s (e.g., Bernard Herrmann's classic score for The Day the Earth Stood Still).

In the UK in this period, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (established in 1958) emerged one of the most productive and widely known electronic music studios in the world, thanks in large measure to their work on the BBC science-fiction series Doctor Who. One of the most influential British electronic artists in this period was Workshop staffer Delia Derbyshire, who added a keen musical ear to her great technical prowess—she is famous for her landmark 1963 electronic realisation of the iconic Doctor Who theme, composed by Ron Grainer.

In 1961 Josef Tal established the Centre for Electronic Music in Israel at The Hebrew University, and in 1962 Hugh Le Caine arrived in Jerusalem to install his Creative Tape Recorder in the centre.[47] In the 1990s Tal conducted, together with Dr Shlomo Markel, in cooperation with the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, and VolkswagenStiftung a research project (Talmark) aimed at the development of a novel musical notation system for electronic music.[48]

Milton Babbitt composed his first electronic work using the synthesizer—his Composition for Synthesizer—which he created using the RCA synthesizer at CPEMC.

For Babbitt, the RCA synthesizer was a dream come true for three reasons. First, the ability to pinpoint and control every musical element precisely. Second, the time needed to realize his elaborate serial structures were brought within practical reach. Third, the question was no longer "What are the limits of the human performer?" but rather "What are the limits of human hearing?[49]

The collaborations also occurred across oceans and continents. In 1961, Ussachevsky invited Varèse to the Columbia-Princeton Studio (CPEMC). Upon arrival, Varese embarked upon a revision of Déserts. He was assisted by Mario Davidovsky and Bülent Arel.[50]

The intense activity occurring at CPEMC and elsewhere inspired the establishment of the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1963 by Morton Subotnick, with additional members Pauline Oliveros, Ramon Sender, Terry Riley, and Anthony Martin.

Later, the Center moved to Mills College, directed by Pauline Oliveros, where it is today known as the Center for Contemporary Music.[51]

Simultaneously in San Francisco, composer Stan Shaff and equipment designer Doug McEachern, presented the first “Audium” concert at San Francisco State College (1962), followed by a work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1963), conceived of as in time, controlled movement of sound in space. Twelve speakers surrounded the audience, four speakers were mounted on a rotating, mobile-like construction above.[52] In an SFMOMA performance the following year (1964), San Francisco Chronicle music critic Alfred Frankenstein commented, “...the possibilities of the space-sound continuum have seldom been so extensively explored.” [53] In 1967, the first Audium, a “sound-space continuum” opened, holding weekly performances through 1970. In 1975, enabled by seed money from the National Endowment for the Arts, a new Audium opened, designed floor to ceiling for spatial sound composition and performance.[54] “There are composers who manipulate sound space by locating multiple speakers at various locations in a performance space and then switching or panning the sound between the sources. In this approach, the composition of spatial manipulation is dependent on the location of the speakers and usually exploits the acoustical properties of the enclosure. Examples include Varese’s Poem Electronique (tape music performed in the Phillips Pavilion of the 1958 World Fair, Brussels) and Stanley Schaff’s Audium installation, currently active in San Francisco.” [55] Through weekly programs (over 4,500 in 40 years), Shaff “sculpts” sound, performing now-digitized spatial works live through 176 speakers.[56]

A well-known example of the use of Moog's full-sized Moog modular synthesizer is the Switched-On Bach album by Wendy Carlos, which triggered a craze for synthesizer music.

Pietro Grossi was an Italian pioneer of computer composition and tape music, who first experimented with electronic techniques in the early sixties. Grossi was a cellist and composer, born in Venice in 1917. He founded the S 2F M (Studio de Fonologia Musicale di Firenze) in 1963 in order to experiment with electronic sound and composition.

Computer music

CSIRAC, the first computer to play music, did so publicly in August 1951 (reference 12).[57] One of the first large-scale public demonstrations of computer music was a pre-recorded national radio broadcast on the NBC radio network program Monitor on February 10, 1962. In 1961, LaFarr Stuart programmed Iowa State University's CYCLONE computer (a derivative of the Illiac) to play simple, recognizable tunes through an amplified speaker that had been attached to the system originally for administrative and diagnostic purposes. An interview with Mr. Stuart accompanied his computer music.

The late 1950s, 1960s and 1970s also saw the development of large mainframe computer synthesis. Starting in 1957, Max Mathews of Bell Labs developed the MUSIC programs, culminating in MUSIC V, a direct digital synthesis language[58]

Live electronics

In America, live electronics were pioneered in the early 1960s by members of Milton Cohen's Space Theater in Ann Arbor, Michigan, including Gordon Mumma and Robert Ashley, by individuals such as David Tudor around 1965, and The Sonic Arts Union, founded in 1966 by Gordon Mumma, Robert Ashley, Alvin Lucier, and David Behrman. ONCE Festivals, featuring multimedia theater music, were organized by Robert Ashley and Gordon Mumma in Ann Arbor between 1958 and 1969. In 1960, John Cage composed Cartridge Music, one of the earliest live-electronic works.[citation needed]

In Europe in 1964, Karlheinz Stockhausen composed Mikrophonie I for tam-tam, hand-held microphones, filters, and potentiometers, and Mixtur for orchestra, four sine-wave generators, and four ring modulators. In 1965 he composed Mikrophonie II for choir, Hammond organ, and ring modulators.[59]

The Jazz composers and musicians Paul Bley and Annette Peacock performed some of the first live concerts in the late 1960s using Moog synthesizers. Peacock made regular use of a customised Moog synthesizer to process her voice on stage and in studio recordings.[citation needed]

In 1966–67, Reed Ghazala discovered and began to teach "circuit bending"—the application of the creative short circuit, a process of chance short-circuiting, creating experimental electronic instruments, exploring sonic elements mainly of timbre and with less regard to pitch or rhythm, and influenced by John Cage’s aleatoric music concept.[60]

Popularization: 1970s to present day

In 1970, Charles Wuorinen composed Time's Encomium, the first Pulitzer Prize winner for an entirely electronic composition.

1970s to early 1980s

Synthesizers

Released in 1970 by Moog Music the Mini-Moog was among the first widely available, portable and relatively affordable synthesizers. It became the most widely used synthesizer in both popular and electronic art music.[61] In 1974 the WDR studio in Cologne acquired an EMS Synthi 100 synthesizer which was used by a number of composers in the production of notable electronic works—amongst others, Rolf Gehlhaar's Fünf deutsche Tänze (1975), Karlheinz Stockhausen's Sirius (1975–76), and John McGuire's Pulse Music III (1978).[62]

IRCAM

IRCAM in Paris became a major center for computer music research and realization and development of the Sogitec 4X computer system,[63] featuring then revolutionary real-time digital signal processing. Pierre Boulez's Répons (1981) for 24 musicians and 6 soloists used the 4X to transform and route soloists to a loudspeaker system.

Rise of popular electronic music

The late 1970s saw the emergence of electropop music, developed by Kraftwerk of Germany and Yellow Magic Orchestra of Japan.[64] In 1979, UK recording artist Gary Numan helped to bring electronic music into the wider marketplace of pop music with his hit "Cars" from the album The Pleasure Principle. Other successful hit electronic singles in the early 1980s included "Just Can't Get Enough" by Depeche Mode, "Don't You Want Me" by The Human League, "Whip It!" by Devo, and finally 1983's "Blue Monday" by New Order, which became the best-selling 12-inch single of all time.[65]

Birth of MIDI

In 1980, a group of musicians and music merchants met to standardize an interface by which new instruments could communicate control instructions with other instruments and the prevalent microcomputer. This standard was dubbed MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface). A paper was authored by Dave Smith of Sequential Circuits and proposed to the Audio Engineering Society in 1981. Then, in August 1983, the MIDI Specification 1.0 was finalized.

The advent of MIDI technology allows a single keystroke, control wheel motion, pedal movement, or command from a microcomputer to activate every device in the studio remotely and in synchrony, with each device responding according to conditions predetermined by the composer.

MIDI instruments and software made powerful control of sophisticated instruments easily affordable by many studios and individuals. Acoustic sounds became reintegrated into studios via sampling and sampled-ROM-based instruments.

Miller Puckette developed graphic signal-processing software for 4X called Max (after Max Mathews) and later ported it to Macintosh (with Dave Zicarelli extending it for Opcode)[66] for real-time MIDI control, bringing algorithmic composition availability to most composers with modest computer programming background.

Digital synthesis

In 1979 the Australian Fairlight company released the Fairlight CMI (Computer Musical Instrument) the first practical polyphonic digital synthesizer/sampler system. In 1983, Yamaha introduced the first stand-alone digital synthesizer, the DX-7. It used frequency modulation synthesis (FM synthesis), first experimented with by John Chowning at Stanford during the late sixties.[67]

Barry Vercoe describes one of his experiences with early computer sounds:

At IRCAM in Paris in 1982, flutist Larry Beauregard had connected his flute to DiGiugno's 4X audio processor, enabling real-time pitch-following. On a Guggenheim at the time, I extended this concept to real-time score-following with automatic synchronized accompaniment, and over the next two years Larry and I gave numerous demonstrations of the computer as a chamber musician, playing Handel flute sonatas, Boulez's Sonatine for flute and piano and by 1984 my own Synapse II for flute and computer—the first piece ever composed expressly for such a setup. A major challenge was finding the right software constructs to support highly sensitive and responsive accompaniment. All of this was pre-MIDI, but the results were impressive even though heavy doses of tempo rubato would continually surprise my Synthetic Performer. In 1985 we solved the tempo rubato problem by incorporating learning from rehearsals (each time you played this way the machine would get better). We were also now tracking violin, since our brilliant, young flautist had contracted a fatal cancer. Moreover, this version used a new standard called MIDI, and here I was ably assisted by former student Miller Puckette, whose initial concepts for this task he later expanded into a program called MAX.[68]

Late 1980s to 1990s

Rise of dance music

In the late 1980s, dance music records made using only electronic instruments became increasingly popular. The trend has continued to the present day with modern nightclubs worldwide regularly playing electronic dance music. Nowadays, electronic/dance music is so popular, that dedicated genre radio stations (e.g., RADIO 538, Q Radio) or TV Channels (e.g., NRJ Dance, MUSIC FORCE EUROPE) exist.

Advancements

In the 1990s, interactive computer-assisted performance started to become possible, with one example described as follows:

Automated Harmonization of Melody in Real Time: An interactive computer system, developed in collaboration with flutist/composer Pedro Eustache, for realtime melodic analysis and harmonic accompaniment. Based on a novel scheme of harmonization devised by Eustache, the software analyzes the tonal melodic function of incoming notes, and instantaneously performs an orchestrated harmonization of the melody. The software was originally designed for performance by Eustache on Yamaha WX7 wind controller, and was used in his composition Tetelestai, premiered in Irvine, California in March 1999.[69]

Other recent developments included the Tod Machover (MIT and IRCAM) composition Begin Again Again for "hypercello", an interactive system of sensors measuring physical movements of the cellist. Max Mathews developed the "Conductor" program for real-time tempo, dynamic and timbre control of a pre-input electronic score. Morton Subotnick released a multimedia CD-ROM All My Hummingbirds Have Alibis.

2000s

In recent years, as computer technology has become more accessible and music software has advanced, interacting with music production technology is now possible using means that bear no relationship to traditional musical performance practices:[70] for instance, laptop performance (laptronica)[71] and live coding.[72] In general, the term Live PA refers to any live performance of electronic music, whether with laptops, synthesizers, or other devices.

In the last decade, a number of software-based virtual studio environments have emerged, with products such as Propellerhead's Reason and Ableton Live finding popular appeal.[73] Such tools provide viable and cost-effective alternatives to typical hardware-based production studios, and thanks to advances in microprocessor technology, it is now possible to create high quality music using little more than a single laptop computer. Such advances have democratized music creation,[74] leading to a massive increase in the amount of home-produced electronic music available to the general public via the internet.

Artists such as Fluker from Australia, can now also individuate their production practice by creating personalized software synthesizers, effects modules, and various composition environments. Devices that once existed exclusively in the hardware domain can easily have virtual counterparts. Some of the more popular software tools for achieving such ends are commercial releases such as Max/Msp and Reaktor and open source packages such as Pure Data, SuperCollider, and ChucK.

Chip music

Chiptune, chipmusic, or chip music is music written in sound formats where many of the sound textures are synthesized or sequenced in real time by a computer or video game console sound chip, sometimes including sample-based synthesis and low bit sample playback. Many chip music devices featured synthesizers in tandem with low rate sample playback.[citation needed]

See also

- Audium (theater)

- Beaver & Krause

- Electronic Sackbut

- New Interfaces for Musical Expression

- Sound installation

- Sound sculpture

- Spectral music

- Tracker music

Footnotes

- ^ "The novelty of making music with electronic instruments has long worn off. The use of electronics to compose, organize, record, mix, color, stretch, randomize, project, perform, and distribute music is now intimately woven into the fabric of modern experience" (Holmes 2002, 1).

- ^ "The stuff of electronic music is electrically produced or modified sounds. ... two basic definitions will help put some of the historical discussion in its place: purely electronic music versus electroacoustic music" (Holmes 2002, 6).

- ^ "Electroacoustic music uses electronics to modify sounds from the natural world. The entire spectrum of worldly sounds provides the source material for this music. This is the domain of microphones, tape recorders and digital samplers... can be associated with live or recorded music. During live performances, natural sounds are modified in real time using electronics. The source of the sound can be anything from ambient noise to live musicians playing conventional instruments" (Holmes 2002, 8).

- ^ "Electronically produced music is part of the mainstream of popular culture. Musical concepts that were once considered radical—the use of environmental sounds, ambient music, turntable music, digital sampling, computer music, the electronic modification of acoustic sounds, and music made from fragments of speech-have now been subsumed by many kinds of popular music. Record store genres including new age, rap, hip-hop, electronica, techno, jazz, and popular song all rely heavily on production values and techniques that originated with classic electronic music" (Holmes 2002, 1). "By the 1990s, electronic music had penetrated every corner of musical life. It extended from ethereal sound-waves played by esoteric experimenters to the thumping syncopation that accompanies every pop record" (Lebrecht 1996, 106).

- ^ Rosen 2008

- ^ Russcol 1972, 67.

- ^ Theremin, BBC h2g2 encyclopaedia project, Undated. Accessed: 05-20-2008.

- ^ Richard Orton and Hugh Davies. "Ondes martenot." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/20343 (accessed February 2, 2011).

- ^ Busoni 1962, 95.

- ^ Busoni 1962, 76–77.

- ^ Russcol 1972, 35-36.

- ^ Quoted in Russcol 1972, 40.

- ^ Russcol 1972, 68.

- ^ Composers using the instrument ultimately include Boulez, Honneger, Jolivet, Koechlin, Messiaen, Milhaud, Tremblay, and Varèse. In 1937, Messiaen wrote Fête des belles eaux for 6 ondes Martenot, and wrote solo parts for it in Trois petites Liturgies de la Présence Divine (1943–44) and the Turangalîla Symphonie (1946–48/90).

- ^ Russcol 1972, 70.

- ^ 120 Years of Electronic Music, The Hammond Novachord (1939)

- ^ "Inventing the Wire Recorder". Recording History. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Tyson, Jeff. "''How Stuff Works'' - "How Movie Sound Works"". Entertainment.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ "Mix Online - 1935 AEG Magnetophone Tape Recorder". Mixonline.com. 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Engel, Friedrich Karl (2006-08). "Walter Weber's Technical Innovation at the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft" (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Krause 2002, abstract.

- ^ "Friedrich Engel and Peter Hammar, ''A Selected History of Magnetic Recording'' (.pdf document), p.6" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Karen Crocker Snell 2006.

- ^ Angus 1984.

- ^ Hammar 1999.

- ^ "Musique Concrete was created in Paris in 1948 from edited collages of everyday noise" (Lebrecht 1996, 107).

- ^ NB: To the pioneers, an electronic work did not exist until it was "realized" in a real-time performance (Holmes 2008, 122).

- ^ Snyder (n.d.).

- ^ Eimert 1972, 349.

- ^ Eimert 1958, 2; Ungeheuer 1992, 117.

- ^ (Lebrecht 1996, 75). "... at Northwest German Radio in Cologne (1953), where the term 'electronic music' was coined to distinguish their pure experiments from musique concrete..." (Lebrecht 1996, 107).

- ^ Stockhausen 1978, 73–76, 78–79.

- ^ "In 1967, just following the world premiere of Hymnen, Stockhausen said this about the electronic music experience: '... Many listeners have projected that strange new music which they experienced—especially in the realm of electronic music—into extraterrestrial space. Even though they are not familiar with it through human experience, they identify it with the fantastic dream world. Several have commented that my electronic music sounds "like on a different star," or "like in outer space." Many have said that when hearing this music, they have sensations as if flying at an infinitely high speed, and then again, as if immobile in an immense space. Thus, extreme words are employed to describe such experience, which are not "objectively" communicable in the sense of an object description, but rather which exist in the subjective fantasy and which are projected into the extraterrestrial space'" (Holmes 2002, 145).

- ^ Johnson 2002, 2.

- ^ Johnson 2002, 4

- ^ "Carolyn Brown [Earle Brown's wife] was to dance in Cunningham's company, while Brown himself was to participate in Cage's 'Project for Music for Magnetic Tape.'... funded by Paul Williams (dedicatee of the 1953 Williams Mix), who—like Robert Rauschenberg—was a former student of Black Mountain College, which Cage and Cunnigham had first visited in the summer of 1948" (Johnson 2002, 20).

- ^ a b c Russcol 1972, 92.

- ^ a b c d e f Luening 1968, 48.

- ^ Luening 1968, 49.

- ^ a b Kurtz 1992, 75-76.

- ^ Anonymous 1972.

- ^ "From at least Louis and Bebbe Barron's soundtrack for 'The Forbidden Planet" onwards, electronic music - in particular synthetic timbre - has impersonated alien worlds in film" (Norman 2004, 32).

- ^ Doornbusch 2005, [page needed].

- ^ Schwartz 1975, 347.

- ^ Harris, Craig. "( Tom Dissevelt > Overview )". allmusic. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Kurtz 1992, 1.

- ^ Gluck, Robert J.: Fifty years of electronic music in Israel, Organised Sound 10(2): 163–180 Cambridge University Press (2005)

- ^ Tal and Markel 2002, 55-62.

- ^ Schwartz 1975, 124.

- ^ Bayly 1982–83, 150.

- ^ "A central figure in post-war electronic art music, Pauline Oliveros [b. 1932] is one of the original members of the San Francisco Tape Music Center (along with Morton Subotnick, Ramon Sender, Terry Riley, and Anthony Martin), which was the resource on the U.S. west coast for electronic music during the 1960s. The Center later moved to Mills College, where she was its first director, and is now called the Center for Contemporary Music." from CD liner notes, "Accordion & Voice," Pauline Oliveros, Record Label: Important, Catalog number IMPREC140: 793447514024.

- ^ Frankenstein, Alfred, 1964

- ^ Frankenstein 1964.

- ^ Loy 1985, 41-48.

- ^ Begault 1994, 208.

- ^ Hertelendy 2008.

- ^ Doornbusch, Paul. "The Music of CSIRAC". Melbourne School of Engineering, Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering.

- ^ Mattis 2001.

- ^ Stockhausen 1971, 51, 57, 66.

- ^ Yabsley, Alex (2007-02-03). "Back to the 8 bit: A Study of Electronic Music Counter-culture". Dot.AY.

This element of embracing errors is at the centre of Circuit Bending, it is about creating sounds that are not supposed to happen and not supposed to be heard (Gard, 2004). In terms of musicality, as with electronic art music, it is primarily concerned with timbre and takes little regard of pitch and rhythm in a classical sense. ... . In a similar vein to Cage's aleatoric music, the art of Bending is dependent on chance, when a person prepares to bend they have no idea of the final outcome.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "In 1969, a portable version of the studio Moog, called the Minimoog Model D, became the most widely used synthesizer in both popular music and electronic art music" (Montanaro 2004, [page needed]).

- ^ Morawska-Büngeler 1988, 52, 55, 107–108.

- ^ Schutterhoef 2007.

- ^ Electronic music at AllMusic

- ^ Bush 2009.

- ^ Ozab 2000.

- ^ Chowning 1973.

- ^ Vercoe 2000, xxviii–xxix.

- ^ Dobrian 2002, Automated Harmonization of Melody in Real Time

- ^ Emmerson 2007, 111–13.

- ^ Emmerson 2007, 80-81.

- ^ Emmerson 2007, 115; Collins 2003.

- ^ 23rd Annual International Dance Music Awards: Best Audio Editing Software of the Year - 1st Abelton Live, 4th Reason. Best Audio DJ Software of the Year - Abelton Live.

- ^ Chadabe 2004, 5–6.

References

- Angus, Robert. 1984. "History of Magnetic Recording, Part One". Audio Magazine (August): 27–33.

- Anonymous. 1972. Liner notes to The Varese Album. Columbia Records MG 31078.

- Bassingthwaighte, Sarah Louise. 2002. "Electroacoustic Music for the Flute". DMA dissertation. Seattle: University of Washington.

- Bayly, Richard. 1982–83. "Ussachevsky on Varèse: An Interview April 24, 1979 at Goucher College," Perspectives of New Music 21 (Fall-Winter 1982 and Spring-Summer 1983):145–51.

- Begault, Durand R. 1994. 3-D Sound for Virtual Reality and Multimedia]. Boston: Academic Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0120847358. Online reprint, NASA Ames Research Center Technical Memorandum facsimile 2000.

- Brick, Howard. 2000. Age of Contradiction: American Thought and Culture in the 1960s. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8700-5 (Originally published: New York: Twayne, 1998)

- Bush, John. 2009. "Song Review: 'Blue Monday'". Allmusic website (Accessed 13 January 2010).

- Busoni, Ferruccio. 1962. '"Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music". Translated by Dr. Th. Baker and originally published in 1911 by G. Schirmer. Reprinted in Three Classics in the Aesthetic of Music: Monsieur Croche the Dilettante Hater, by Claude Debussy; Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music, by Ferruccio Busoni; Essays before a Sonata, by Charles E. Ives, 73–102. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

- Chadabe Joel. 1997. Electric Sound: The Past and Promise of Electronic Music. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Chadabe, Joel. 2004. "Electronic Music and Life". Organised Sound 9, no. 1: 3–6.

- Chowning, John. 1973. "The Synthesis of Complex Audio Spectra by Means of Frequency Modulation". Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 21, no. 7:526–34.

- Collins, Nick. 2003. "Generative Music and Laptop Performance". Contemporary Music Review 22, no. 4:67-79.

- Dobrian, Christopher. 2002. "Current Research Projects". Accessed 29 June 2007.

- Donhauser, Peter. 2007. Elektrische Klangmaschinen. Vienna: Boehlau.

- Doornbusch, Paul. 2005. The Music of CSIRAC, Australia's First Computer Music, with accompanying CD recording. [Australia]: Common Ground Publishers. ISBN 1-86335-569-3

- Eimert, Herbert. 1958. "What Is Electronic Music?" Die Reihe 1 (English edition): 1–10.

- Eimert, Herbert. 1972. "How Electronic Music Began." Musical Times 113, no. 1550 (April): 347 & 349. (First published in German in Melos 39 (Jan.-Feb. 1972): 42–44.)

- Emmerson, Simon. 1986. The Language of Electroacoustic Music. London: Macmillan.

- Emmerson, Simon (ed.). 2000. Music, Electronic Media, and Culture. Aldershot (Hants.), Burlington (VT): Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-0109-9

- Emmerson, Simon. 2007. Living Electronic Music. Aldershot (Hants.), Burlington (VT): Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5546-6 (cloth) ISBN 0-7546-5548-2 (pbk)

- Frankenstein, Alfred. 1964. “Space-Sound Continuum in Total Darkness”. San Francisco Chronicle (October 17). History of Experimental Music in Northern California

- Gard, Stephen. 2004. "Nasty Noises: ‘Error’ as a Compositional Element". Sydney Conservatorium of Music, Sydney eScholarship Repository.

- Griffiths, Paul. 1995. Modern Music and After: Directions Since 1945. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816578-1 (cloth) ISBN 0-19-816511-0 (pbk)

- Hammar, Peter. 1999. "John T. Mullin: The Man Who Put Bing Crosby on Tape. Mix Online (1 October). (Accessed 13 January 2010).

- Hertelendy, Paul. 2008. "Spatial Sound’s Longest Running One-Man Show". artssf.com Dec.7,2008 (Accessed March 3, 2011)

- Holmes, Thomas B. 2002. Electronic and Experimental Music: Pioneers in Technology and Composition. Second edition. London: Routledge Music/Songbooks. ISBN 0-415-93643-8 (cloth) ISBN 0-415-93644-6 (pbk)

- Holmes, Thom. 2008. Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture, third edition. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-95781-8 (cloth); ISBN 0-415-95782-6 (pbk); ISBN 0-203-92959-4 (ebook).

- Krause, Manfred. 2002. "The Legendary 'Magnetophon' of AEG". Audio Engineering Society E-Library. AES Convention 112 (April), paper number 5605. Abstract.

- Kurtz, Michael. 1992. Stockhausen: A Biography. Trans. by Richard Toop. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-14323-7

- Johnson, Steven. 2002. The New York Schools of Music and Visual Arts: John Cage, Morton Feldman. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93694-2

- Lebrecht, Norman. 1996. The Companion to 20th-Century Music. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80734-3 (pbk)

- Loy, Gareth. 1985. "About Audium - A Conversation with Stanley Shaff". ‘’Computer Music Journal’’ Summer 1985, Volume 9, Number 2, pgs. 41-48.

- Luening, Otto. 1964. "Some Random Remarks About Electronic Music", Journal of Music Theory 8, no. 1 (Spring): 89–98.

- Luening, Otto. 1968. "An Unfinished History of Electronic Music". Music Educators Journal 55, no. 3 (November): 42–49, 135–42, 145.

- Macon, Edward L. 1997. Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509887-0

- Mattis, Olivia. 2001. "Mathews, Max V(ernon)". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrell. London: Macmillan.

- Montanaro, Larisa Katherine. 2004. "A Singer’s Guide to Performing Works for Voice and Electronics". DMA thesis. Austin: The University of Texas at Austin.

- Morawska-Büngeler, Marietta. 1988. Schwingende Elektronen: Eine Dokumentation über das Studio für Elektronische Musik des Westdeutschen Rundfunk in Köln 1951–1986. Cologne-Rodenkirchen: P. J. Tonger Musikverlag.

- Norman, Katharine. 2004. Sounding Art: Eight Literary Excursions through Electronic Music. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-0426-8

- Ozab, David. 2000. "Beyond the Barline: One Down, Two to Go". ATPM (About This Particular Macintosh) website (May). (Accessed 13 January 2010).

- Peyser, Joan. 1995. The Music of My Time. White Plains, N.Y.: Pro/AM Music Resources Inc.; London: Kahn and Averill. ISBN 0-912483-99-7; ISBN 1-871082-57-9

- Rappaport, Scott. 2007. "Digital Arts and New Media Grad Students Collaborate Musically across Three Time Zones". UC Santa Cruz Currents Online (2 April).

- Roads, Curtis. 1996. The Computer Music Tutorial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-18158-4 (cloth) ISBN 0-262-68082-3 (pbk)

- Rosen, Jody. 2008. "Researchers Play Tune Recorded before Edison". New York Times (27 March).

- Russcol, Herbert. 1972. The Liberation of Sound: An Introduction to Electronic Music. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Russolo, Luigi. 1913. L'arte dei rumori: manifesto futurista. Manifesti del movimento futurista 14. Milano: Direzione del movimento futurista. English version as The Art of Noise: Futurist Manifesto 1913, translated by Robert Filliou. A Great Bear Pamphlet 18. New York: Something Else Press, 1967. Second English version as The Art of Noises, translated from the Italian with an introduction by Barclay Brown. Monographs in Musicology no. 6. New York: Pendragon Press, 1986. ISBN 0918728576.

- Schutterhoef, Arie van. 2007. "Sogitec 4X". Knorretje, een Nederlandse Wiki over muziek, geluid, soft- en hardware. (Accessed 13 January 2010).

- Schwartz, Elliott. 1975. Electronic Music New York: Praeger.

- Snell, Karen Crocker. 2006. "The Man Behind The Sound". Santa Clara University Online Magazine (Summer) (Accessed 13 January 2010).

- Snyder, Jeff. [n.d.]. "Pierre Schaeffer: Inventor of Musique Concrete". Accessed May 2002.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1971. Texte zur Musik 3, edited by Dieter Schnebel. DuMont Dokumente. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag. ISBN 3-7701-0493-5

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1978. Texte zur Musik 4, edited by Christoph von Blumröder. DuMont Dokumente. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag. ISBN 3-7701-1078-1

- Tal, Josef, and Shlomo Markel. 2002. Musica Nova in the Third Millennium. Tel-Aviv: Israel Music Institute. ISBN 965-90565-0-8. Also published in German, as Musica Nova im dritten Millenium. Tel-Aviv: Israel Music Institute. ISBN 965-90565-0-8

- Ungeheuer, Elena. 1992. Wie die elektronische Musik "erfunden" wurde: Quellenstudie zu Werner Meyer-Epplers musikalischem Entwurf zwischen 1949 und 1953. Kölner Schriften zur neuen Musik 2. Mainz and New York: Schott. ISBN 3-7957-1891-0

- Vercoe, Barry. 2000. "Forward," in The Csound Book: Perspectives in Software Synthesis, Sound Design, Signal Processing, and Programming, edited by Richard Boulanger, xxvii–xxx. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Watson, Scott. 2005. "A Return to Modernism". Music Education Technology Magazine (February)

- Weidenaar, Reynold. 1995. Magic Music from the Telharmonium: The Story of the First Music Synthesizer. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, Inc.. ISBN 0-8108-2692-5

- Zimmer, Dave. 2000. Crosby, Stills, and Nash: The Authorized Biography. Photography by Henry Diltz. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80974-5

Further reading

- Bogdanov, Vladimir, Chris Woodstra, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, and John Bush (editors). 2001. The All Music Guide to Electronica: The Definitive Guide to Electronic Music. AMG Allmusic Series. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-628-9

- Cummins, James. 2008. Ambrosia: About a Culture - An Investigation of Electronica Music and Party Culture. Toronto, ON: Clark-Nova Books. ISBN 978-0-9784892-1-2

- Heifetz, Robin J. (ed.). 1989. "On The Wires of Our Nerves: The Art of Electroacoustic Music". Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8387-5155-5

- Kahn, Douglas. 1999. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-11243-4 New edition 2001, ISBN 0-262-61172-4

- Kettlewell, Ben. 2001. Electronic Music Pioneers. [N.p.]: Course Technology, Inc. ISBN 1-931140-17-0

- Licata, Thomas (ed.). 2002. Electroacoustic Music: Analytical Perspectives. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31420-9

- Manning, Peter. 2004. Electronic and Computer Music. Revised and expanded edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514484-8 (cloth) ISBN 0-19-517085-7 (pbk)

- Prendergast, Mark. 2001. The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Trance: The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age. Forward [sic] by Brian Eno. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-4213-9, ISBN 1-58234-134-6 (hardcover eds.) ISBN 1-58234-323-3 (paper)

- Reynolds, Simon. 1998. Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 0-330-35056-0 (US title, Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998 ISBN

0316741116; New York: Routledge, 1999 ISBN 0-415-92373-5)

- Schaefer, John. 1987. New Sounds: A Listener's Guide to New Music. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-097081-2

- Shapiro, Peter (editor). 2000. Modulations: a History of Electronic Music: Throbbing Words on Sound. New York: Caipirinha Productions ISBN 1-891024-06-X

- Sicko, Dan. 1999. Techno Rebels: The Renegades of Electronic Funk. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-8428-0

- Edward A. Shanken, Art and Electronic Media. London: Phaidon, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7148-4782-5

External links

- A timeline of electronic music

- A chronology of computer and electronic music

- Pioneers of electronic music - A series of articles highlighting pioneers of electronic music

- History of electronic musical instruments

- Art of the States: electronic - Small collection of electronic works by American composers

- CSIRAC homepage – From the Computation Laboratory at the University of Melbourne's Dept of Computer Science and Software Engineering

- Partynews.hu Electronic Music Partynews , Historys , Programs , Events

- Technotika.de Elektronische Events in Frankfurt a.M. (Germany)

- Explore electronic music genres - Primer on some of the types of electronic popular music

- XLR8R.com - Leading voice for electronic music in the United States

- Electronic Music Foundation

- Computer Music Center

- Leading Australian Electronic Music Portal

- Read more about Swedish Techno