Manchu people: Difference between revisions

WhisperToMe (talk | contribs) |

remove the information without sources; partially rewrite; add information; add references and citations |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect|Manchu}} |

{{redirect|Manchu}} |

||

{{Infobox ethnic group |

{{Infobox ethnic group |

||

|group = Manchu<br>[[File:Manju.png| |

|group = <big>Manchu</big><br>[[File:Manju.png|24px|link=wikt:ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ]]<br> |

||

|image = [[File:Manchu celeb 1.jpg|320px]] |

|image = [[File:Manchu celeb 1.jpg|320px]] |

||

|caption = |

|caption = |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

=== Origins and early history === |

=== Origins and early history === |

||

{{further|Sushen|Mogher|Jurchen people}} |

{{further|Sushen|Mogher|Jurchen people}} |

||

| Line 60: | Line 59: | ||

The [[Yuan Dynasty|Mongol domination of China]] was replaced by [[Ming Dynasty]] in 1368. In 1387, Ming defeated Nahacu's Mongol resisting forces who settled in [[Haixi Jurchens|Haixi area]]<ref>{{harvnb|Peterson|2006|p=11}}</ref> and began to summon the Jurchen tribes to pay tribute<ref name="开国史21">{{harvnb|Meng|2006|p=21}}</ref> At the time, some Jurchen tribes were vassal to [[Joseon|Joseon dynasty of Korea]] such as Odoli and Huligai.<ref>{{harvnb|Meng|2006|pp=97, 120}}</ref> Their elites served in Korean royal bodyguard.<ref name="剑桥15">{{harvnb|Peterson|2006|p=15}}</ref> However, their relationship discontinued by Ming, because Ming was planning to make Jurchens their protection of border. Korea had to allow it since itself was in Ming's tribute system.<ref name="剑桥15"/> In 1403, Ahacu, chieftain of Huligai, paid tribute to [[Yongle Emperor|Yongle Emperor of Ming]]. Soon after that, Möngke Temür, chieftain of Odoli, went to tribute from Korea, too. [[Yi Seong-gye]], the Taejo of Joseon requested Ming to send Möngke Temür back but rejected.<ref>{{harvnb|Meng|2006|p=120}}</ref> Since then, more and more Jurchen tribes presented tribute to Ming in succession.<ref name="开国史21"/> They were divided in 384 guards by Ming.<ref name="剑桥15"/> |

The [[Yuan Dynasty|Mongol domination of China]] was replaced by [[Ming Dynasty]] in 1368. In 1387, Ming defeated Nahacu's Mongol resisting forces who settled in [[Haixi Jurchens|Haixi area]]<ref>{{harvnb|Peterson|2006|p=11}}</ref> and began to summon the Jurchen tribes to pay tribute<ref name="开国史21">{{harvnb|Meng|2006|p=21}}</ref> At the time, some Jurchen tribes were vassal to [[Joseon|Joseon dynasty of Korea]] such as Odoli and Huligai.<ref>{{harvnb|Meng|2006|pp=97, 120}}</ref> Their elites served in Korean royal bodyguard.<ref name="剑桥15">{{harvnb|Peterson|2006|p=15}}</ref> However, their relationship discontinued by Ming, because Ming was planning to make Jurchens their protection of border. Korea had to allow it since itself was in Ming's tribute system.<ref name="剑桥15"/> In 1403, Ahacu, chieftain of Huligai, paid tribute to [[Yongle Emperor|Yongle Emperor of Ming]]. Soon after that, Möngke Temür, chieftain of Odoli, went to tribute from Korea, too. [[Yi Seong-gye]], the Taejo of Joseon requested Ming to send Möngke Temür back but rejected.<ref>{{harvnb|Meng|2006|p=120}}</ref> Since then, more and more Jurchen tribes presented tribute to Ming in succession.<ref name="开国史21"/> They were divided in 384 guards by Ming.<ref name="剑桥15"/> |

||

In 1449, [[Mongol]] [[Mongolian nobility|taishi]] [[Esen taishi|Esen]] assulted Ming Dynasty and captured [[Zhengtong Emperor]] in [[Tumu Crisis|Tumu]]. Some Jurchen guards in [[Jianzhou]] and [[Haixi Jurchens|Haixi]] coorperated with Esen's action,<ref>{{harvnb|Writing Group of Manchu Brief History|2009|p=185}}</ref> but more were also attacked by the Mongol invasion. A large number of Jurchen chieftains lost their hereditary certificate which was granted by Ming.<ref name="开国史19">{{harvnb|Meng|2006|p=19}}</ref> They had to present tribute as secretariats (中书舍人) with much less award from Ming court than they were heads of guards which was not joyful to the them.<ref name="开国史19"/> Since then, Jurchen guards gradually went out of Ming's control.<ref name="开国史19"/> Some tribal leaders even publically plundered Ming's area, such as [[Cungšan]]{{#tag:ref|Cungšan was considered as Nurhaci's direct ancestor by some viewpoints<ref name="开国史19">{{harvnb|Meng|2006|p=130}}</ref>, but disagreements also exsit.<ref>{{harvnb|Peterson|2006|p=28}}</ref>|group=note}} and [[:zh:王杲|Wang Gao]]. Approximately in this period, the Jurchen scripts was offcially abandoned.<ref>{{harvnb|Jin|2006|p=120}}</ref> More Jurchens adopted Mongolian as their writting language and the less used Chinese.<ref name="听雨丛谈152">{{harvnb|Fuge|1984|p=152}}</ref> |

|||

===Manchu reign of China=== |

===Manchu reign of China=== |

||

{{further|Manchu conquest of China|Qing Dynasty}} |

{{further|Eight Banners|Manchu conquest of China|Qing Dynasty}} |

||

[[File:清 佚名 《清太祖天命皇帝朝服像》.jpg|thumb|right|[[Nurhaci]]]] |

[[File:清 佚名 《清太祖天命皇帝朝服像》.jpg|thumb|right|an imperial potrait of [[Nurhaci]]]] |

||

A century after the chaos started in Jurchen's land, [[Nurhaci]], a chieftain of Jianzhou Left Guard, started his ambition as a revenge of Ming's manslaughter of his grandfather and father in 1583.<ref>{{harvnb|Zhao|1998|p=2}}</ref> He reunified Jurchen tribes, established a military system called "[[Eight Banners]]" to organized Jurchen soldiers as "Bannermen" and ordered his scholar Erdeni and minister Gagai to create a new Jurchen script (later known as [[Manchu alphabet|Manchu script]]) by referencing [[traditional Mongolian alphabet]].<ref>{{harvnb|Yan|2006|pp=71, 88, 116, 137}}</ref> |

|||

In 1616, [[Nurhaci]] broke away from the power of the decaying [[Ming Dynasty]] and established the Later Jin Dynasty ([[Manchu language|Manchu]]:{{MongolUnicode|ᠠᠮᠠᡤᠠ<br>ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ<br>ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ}}, [[Transliterations of Manchu|Möllendorff]]: amaga aisin gurun), domestically called the State of Manchu ([[Manchu language|Manchu]]:{{MongolUnicode|ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ<br>ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ}}, [[Transliterations of Manchu|Möllendorff]]: manju gurun), and unified Manchu tribes, establishing (or at least expanding) the Manchu [[Banner system]], a military structure which made their forces quite resilient in the face of superior Ming Dynasty numbers in the field. Nurhaci later conquered [[Mukden]] (modern-day Shenyang) and built it into the new capital in 1621. |

|||

In 1603, Nurhaci was recognized as Sure Kundulen Khan ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᠰᡠᡵᡝ<br>ᡴᡠᠨᡩᡠᠯᡝᠨ<br>ᡥᠠᠨ}}|v=sure kundulen han}}, "wise and respected khan") by his Khalkha Mongol allies.<ref name="ManchuWay56">{{harvnb|Elliott|2001|p=56}}</ref> 13 years later (1616), he publically throned and proclaimed himself Genggiyen Khan ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᡤᡝᠩᡤᡳᠶᡝᠨ<br>ᡥᠠᠨ}}|v=genggiyen han}}, "bright khan") of Later Jin Dynasty ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᠠᠮᠠᡤᠠ<br>ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ<br>ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ}}|v=amaga aisin gurun}}{{#tag:ref|Aka. Manchu State ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ<br>ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ|v=manju gurun}}<ref>{{harvnb|Various authors|2008|p=283 (Manchu Veritable Records)}}</ref>)}}|group=note}}, 后金) and then eventually launched his attack on Ming Dynasty.<ref name="ManchuWay56"/> Nurhaci moved the capital to [[Mukden]] after his conquest of Liaodong.<ref>{{harvnb|Yan|2006|p=282}}</ref> In 1635, his son and successor [[Hong Taiji]] changed the ethnic group Jurchen ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᠵᡠᡧᡝᠨ}}|v=jušen}}) to Manchu.<ref name="太宗实录满洲">{{harvnb|Various authors|2008|pp=330–331 (Taizong period)}}</ref> A year later, Hong Taiji proclaimed himself the emperor of [[Qing Dynasty]] ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᡩᠠᡳᠴᡳᠩ<br>ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ}}|v=daicing gurun{{#tag:ref|The meaning of "daicing" is debatable. It has been reported that the word was imported from Mongolian means "fighting country"<ref>[http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical_nmgmzdxxb-shkxb200502005.aspx A Tentative Discussion about Its Origin and Meaning of Daicing as a Name of a State (simplified Chinese)]</ref>|group=note}}}}).<ref>{{harvnb|Du|1997|p=15}}</ref> With general [[Wu Sangui]]'s support, Qing Empire made a breakthrough to mainland China in 1644. After defeated [[Li Zicheng]], they moved the capital to Beijing in the same year.<ref>{{harvnb|Du|1997|pp=19-20}}</ref> |

|||

In 1636, Nurhaci's son [[Hong Taiji]], reorganized the Manchus, including those other groups (such as Hans and Mongols) who had joined them, changed the nation's name to ''Qing Empire'', and formally changed the name of the ethnic designation to ''Manchu'', outlawing use of the name ''Jurchen''. |

|||

According to legend, the name was chosen because Hong Taiji's father, [[Nurhaci]], had believed himself to be a reincarnation of the bodhisattva [[Manjusri]]. |

|||

When Beijing was captured by [[Li Zicheng]]'s peasant rebels in 1644, the last [[Ming Dynasty|Ming]] Emperor [[Chongzhen]] committed suicide. The Manchu then allied with Ming Dynasty general [[Wu Sangui]] and seized control of Beijing, which became the new capital of the Qing dynasty. Over the next two decades, the Manchu took command of all of China and defended against Russian hostilities in [[Russian–Manchu border conflicts]]. |

|||

For political purposes, the early Manchu emperors took wives descended from the Mongol Great Khans, so that their descendants (such as the [[Kangxi]] Emperor) would also be seen as legitimate heirs of the Mongol-ruled [[Yuan dynasty]]. During the Qing Dynasty, the Manchu government made efforts to preserve Manchu culture and language. These efforts were largely unsuccessful in that Manchus gradually adopted the customs and language of the surrounding Han Chinese and, by the 19th century, spoken Manchu was rarely used even in the Imperial court. Written Manchu, however, was still used for the keeping of records and communication between the emperor and the Banner officials until the collapse of the dynasty. The Qing dynasty also maintained a system of dual appointments in which all major imperial offices would have a Manchu and a Han Chinese member. Because of the small number of Manchus, this ensured that a large fraction of them would be government officials. |

|||

While the Manchu ruling elite at the Beijing imperial court and posts of authority throughout China increasingly adopted Chinese culture, the Qing imperial government viewed the Manchu communities (as well as those of various tribal people) in Manchuria as a place where traditional Manchu virtues could be preserved, and as a reservoir of military manpower fully dedicated to the regime.<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|pp=182–184}}</ref> The emperors tried to protect the traditional way of life of the Manchus (as well as various tribal people) in the central and northern Manchuria by a variety of means, in particular, restricting the migration of Chinese colonists to the region. This ideal, however, had to be balanced with practical needs, such as maintaining the defense against the Russians and the Mongols, supplying government farms with skilled work force, and running trade in the region's products, which resulted in a continuous trickle of Chinese convicts, workers, and merchants to the north-east.<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|pp=20–23,78–90,112–115}}</ref> |

While the Manchu ruling elite at the Beijing imperial court and posts of authority throughout China increasingly adopted Chinese culture, the Qing imperial government viewed the Manchu communities (as well as those of various tribal people) in Manchuria as a place where traditional Manchu virtues could be preserved, and as a reservoir of military manpower fully dedicated to the regime.<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|pp=182–184}}</ref> The emperors tried to protect the traditional way of life of the Manchus (as well as various tribal people) in the central and northern Manchuria by a variety of means, in particular, restricting the migration of Chinese colonists to the region. This ideal, however, had to be balanced with practical needs, such as maintaining the defense against the Russians and the Mongols, supplying government farms with skilled work force, and running trade in the region's products, which resulted in a continuous trickle of Chinese convicts, workers, and merchants to the north-east.<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|pp=20–23,78–90,112–115}}</ref> |

||

However, this policy of artificially isolating the Manchus of the north-east from the rest of China could not last forever. In the 1850s, large numbers of the Manchu bannermen were sent to central China to fight the [[Taiping Rebellion|Taiping]] rebels. (For example, just the [[Heilongjiang]] province - which at the time included only the northern part of today's Heilongjiang - contributed 67,730 bannermen to the campaign, of which merely 10-20% survived).<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|p=117}}</ref> Those few who returned were demoralized and often exposed to [[opium]] addiction.<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|pp=124–125}}</ref> In 1860, in the aftermath of the [[Amur Annexation|loss]] of the "[[Outer Manchuria]]", and with the imperial and provincial governments in deep financial trouble, parts of Manchuria became officially open to [[Chuang Guandong|Chinese settlement]];<ref name=lee103>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|p=103,sq}}</ref> within a few decades, the Manchus became a minority in most of Manchuria's districts. |

However, this policy of artificially isolating the Manchus of the north-east from the rest of China could not last forever. In the 1850s, large numbers of the Manchu bannermen were sent to central China to fight the [[Taiping Rebellion|Taiping]] rebels. (For example, just the [[Heilongjiang]] province - which at the time included only the northern part of today's Heilongjiang - contributed 67,730 bannermen to the campaign, of which merely 10-20% survived).<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|p=117}}</ref> Those few who returned were demoralized and often exposed to [[opium]] addiction.<ref>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|pp=124–125}}</ref> In 1860, in the aftermath of the [[Amur Annexation|loss]] of the "[[Outer Manchuria]]", and with the imperial and provincial governments in deep financial trouble, parts of Manchuria became officially open to [[Chuang Guandong|Chinese settlement]];<ref name=lee103>{{harvnb|Lee|1970|p=103,sq}}</ref> within a few decades, the Manchus became a minority in most of Manchuria's districts. |

||

During the [[Russian Invasion of Northern and Central Manchuria (1900)]], the [[Russian Empire]] annihilated many bannermen, each falling one at a time against a five pronged Russian invasion. Thousands fled south. In many areas, such as the [[Aigun]] District on the [[Amur River|Amur]], the Russian [[Cossacks]] looted their villages and property and then razed them.<ref>{{harvnb|Shirokogorov|1924|p=4}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=72}}</ref> |

|||

===Modern days=== |

===Modern days=== |

||

[[File:Puyi-Manchukuo.jpg|thumb|left|[[Puyi]], "[[the last emperor]]"]] |

|||

As the end of the Qing Dynasty approached, [[anti-Qing sentiment|Manchus were portrayed as outside colonizers]] by [[Chinese nationalism|Chinese nationalists]] such as [[Sun Yat-Sen]], even though the Republican revolution he brought about was supported by many reform-minded Manchu officials and military officers.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=265}}</ref> This portrayal dissipated somewhat after the 1911 revolution as the new Republic of China now sought to [[Five Races Under One Union|include]] Manchus within its [[Zhonghua minzu|national identity]].<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=275}}</ref> |

As the end of the Qing Dynasty approached, [[anti-Qing sentiment|Manchus were portrayed as outside colonizers]] by [[Chinese nationalism|Chinese nationalists]] such as [[Sun Yat-Sen]], even though the Republican revolution he brought about was supported by many reform-minded Manchu officials and military officers.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=265}}</ref> This portrayal dissipated somewhat after the 1911 revolution as the new Republic of China now sought to [[Five Races Under One Union|include]] Manchus within its [[Zhonghua minzu|national identity]].<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=275}}</ref> |

||

| Line 86: | Line 81: | ||

Until 1924, the government continued to pay stipends to Manchu bannermen; however, many cut their links with their banners and took on Han-style names in shame and to avoid persecution.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=270}}</ref> The official total of Manchu fell by more than half during this period, as they refused to admit to their ethnicity when asked by government officials or other outsiders.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|pp=270, 283}}</ref> |

Until 1924, the government continued to pay stipends to Manchu bannermen; however, many cut their links with their banners and took on Han-style names in shame and to avoid persecution.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=270}}</ref> The official total of Manchu fell by more than half during this period, as they refused to admit to their ethnicity when asked by government officials or other outsiders.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|pp=270, 283}}</ref> |

||

In 1931, |

In 1931, as a follow-up action of [[Mukden Incident]], [[Manchukuo]], a puppet state in Manchuria, was created by [[Imperial Japan]] which was nominally ruled by the deposed Emperor [[Puyi]]. Although the nation's name was related to Manchus, it is actually a complete new country for all the ethnicities in Manchuria<ref>{{harvnb|Puyi|2007|pp=223–224}}</ref> and was opposed by many Manchus who fought against Japan in [[World War II]], too.<ref>{{harvnb|Writing Group of Manchu Brief History|2009|p=185}}</ref> Manchukuo had a majority [[Han Chinese|Han]] population, largely due to internal migration from China. The country was abolished at the end of the World War after the [[Red Army|Soviet]] [[Soviet invasion of Manchuria|invasion of Manchuria]], with its territory incorporated again into China. |

||

The People's Republic of China recognised the Manchu as one of the country's official minorities in 1952.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=277}}</ref> In the 1953 census, 2.5 million people identified themselves as Manchu.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=276}}</ref> The Communist government also attempted to improve the treatment of Manchu people; some Manchu people who had hidden their ancestry during the period of KMT rule thus became more comfortable to reveal their ancestry, such as the writer [[Lao She]], who began to include Manchu characters in his fictional works in the 1950s (in contrast to his earlier works which had none).<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=280}}</ref> Between 1982 and 1990, the official count of Manchu people more than doubled from 4,299,159 to 9,821,180, making them China's fastest-growing ethnic minority.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=282}}</ref> In fact, however, this growth was not due to natural increase, but instead people formerly registered as Han applying for official recognition as Manchu.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=283}}</ref> |

The People's Republic of China recognised the Manchu as one of the country's official minorities in 1952.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=277}}</ref> In the 1953 census, 2.5 million people identified themselves as Manchu.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=276}}</ref> The Communist government also attempted to improve the treatment of Manchu people; some Manchu people who had hidden their ancestry during the period of KMT rule thus became more comfortable to reveal their ancestry, such as the writer [[Lao She]], who began to include Manchu characters in his fictional works in the 1950s (in contrast to his earlier works which had none).<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=280}}</ref> Between 1982 and 1990, the official count of Manchu people more than doubled from 4,299,159 to 9,821,180, making them China's fastest-growing ethnic minority.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=282}}</ref> In fact, however, this growth was not due to natural increase, but instead people formerly registered as Han applying for official recognition as Manchu.<ref>{{harvnb|Rhoads|2000|p=283}}</ref> |

||

| Line 1,532: | Line 1,527: | ||

{{Main|Manchu alphabet}} |

{{Main|Manchu alphabet}} |

||

[[File:Wikipedia in Manchu.png|80px|thumb|'''[[Wikipedia]]''' in Manchu script]] |

[[File:Wikipedia in Manchu.png|80px|thumb|'''[[Wikipedia]]''' in Manchu script]] |

||

Jurchens, ancestors of the Manchu, had created Jurchen script in the Jin Dynasty. After Jin collapsed, Jurchen script was gradually lost. In the [[Ming Dynasty|Ming period]], 60%-70% of Jurchens used Mongolian script to write letters and 30%-40% of Jurchens used Chinese characters.<ref |

Jurchens, ancestors of the Manchu, had created Jurchen script in the Jin Dynasty. After Jin collapsed, Jurchen script was gradually lost. In the [[Ming Dynasty|Ming period]], 60%-70% of Jurchens used Mongolian script to write letters and 30%-40% of Jurchens used Chinese characters.<ref name="听雨丛谈152"/> This persisted until Nurhaci revolted against the Ming reign. Nurhaci considered it a major impediment that his people lacked a script of their own, so he commanded his scholars, Gagai and Eldeni, to create Manchu characters by reference to Mongolian scripts.<ref>{{harvnb|Jiang|1980|p=4}}</ref> They dutifully complied with the Khan's order and created Manchu script, which is called "script without dots and circles" ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᡨᠣᠩᡴᡳ<br>ᡶᡠᡴᠠ<br>ᠠᡴᡡ<br>ᡥᡝᡵᡤᡝᠨ}}|v=tongki fuka akū hergen}}; 无圈点满文) or "old Manchu script" (老满文).<ref>{{harvnb|Liu|Zhao|Zhao|1997|p=3 (Preface)}}</ref> Due to its hurried creation, the script has its defects. Some vowels and consonants were difficult to distinguish.<ref>{{harvnb|Ortai|1985|pp=5324–5327}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Tong|2009|pp=11–17}}</ref> Shortly afterwards, their successor Dahai used dots and circles to distinguish vowels, aspirated and non-aspirated consonants and thus completed the script. His achievement is called "script with dots and circles" or "new Manchu script".<ref>{{harvnb|Anonymous|1990|pp=1196–1197}}</ref> |

||

====Current situation==== |

====Current situation==== |

||

| Line 1,606: | Line 1,601: | ||

[[File:Hunting Journey on Horseback.jpg|thumb|left|Painting of Qianlong Emperor hunting]] |

[[File:Hunting Journey on Horseback.jpg|thumb|left|Painting of Qianlong Emperor hunting]] |

||

[[File:Dutch enthusiast of Manchu archery demonstrates Manchu shooting skills 1.jpg|thumb|300px|A Dutch researcher of Manchu archery demonstrates Manchu traditional shooting skills.<ref>[http://www.manchuarchery.org/?q=technique Fe Doro Manchu Archery: Technique]</ref>]] |

[[File:Dutch enthusiast of Manchu archery demonstrates Manchu shooting skills 1.jpg|thumb|300px|A Dutch researcher of Manchu archery demonstrates Manchu traditional shooting skills.<ref>[http://www.manchuarchery.org/?q=technique Fe Doro Manchu Archery: Technique]</ref>]] |

||

Riding and |

Riding and archery ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠮᠨᡳᠶᠠᠨ}}|v=niyamniyan}}) is significant to the Manchu. They were well-trained horsemen from their teenage<ref>{{harvnb|Yi|1978|p=44}}</ref> years. [[Hong Taiji]], the Qing Taizong emperor, said, "Riding and Archery is the most important martial art of our country".<ref>{{harvnb|Jiang|1980|p=46}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Various authors|2008|p=446 (Taizong period)}}</ref> Every generation of the Qing dynasty treasured Riding and Archery the most.<ref name="八旗子弟108"/> Every spring and fall, from ordinary Manchus to aristocrats, all had to take a riding and archery test. Their test results could even affect their rank in the nobility.<ref>{{harvnb|Liu|2008|p=93}}</ref> The Manchus of the early Qing had excellent shooting skills and their arrows were reputed to be capable of penetrating two people.<ref name="八旗子弟94" >{{harvnb|Liu|2008|p=94}}</ref> |

||

From the middle period of Qing, archery became more a form of entertainment, in the form of games such as, hunting swans, shooting fabric or silk target. The most difficult is shooting a candle hanging in the air at night.<ref name="八旗子弟95" >{{harvnb|Liu|2008|p=95}}</ref> Gambling was banned in the Qing reign but there was no limitation on Manchus engaging in shooting skill contests. It was common to see Manchus putting signs in front of their houses to invite challenges.<ref name="八旗子弟95" /> After the [[Qianlong]] period, Manchus gradually neglected the practice of riding and archery, even though their rulers tried their best to encourage Manchus to continue their riding and archery traditions,<ref name="八旗子弟94" /> but the tradition is still kept among some Manchus even nowadays.<ref>[http://www.manchus.cn/plus/view.php?aid=9404 Manchu Archery in Heritage Day (simplified Chinese)]</ref> |

From the middle period of Qing, archery became more a form of entertainment, in the form of games such as, hunting swans, shooting fabric or silk target. The most difficult is shooting a candle hanging in the air at night.<ref name="八旗子弟95" >{{harvnb|Liu|2008|p=95}}</ref> Gambling was banned in the Qing reign but there was no limitation on Manchus engaging in shooting skill contests. It was common to see Manchus putting signs in front of their houses to invite challenges.<ref name="八旗子弟95" /> After the [[Qianlong]] period, Manchus gradually neglected the practice of riding and archery, even though their rulers tried their best to encourage Manchus to continue their riding and archery traditions,<ref name="八旗子弟94" /> but the tradition is still kept among some Manchus even nowadays.<ref>[http://www.manchus.cn/plus/view.php?aid=9404 Manchu Archery in Heritage Day (simplified Chinese)]</ref> |

||

| Line 1,612: | Line 1,607: | ||

====Manchu wrestling==== |

====Manchu wrestling==== |

||

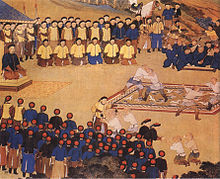

[[File:Banquets-at-a-frontier-fortress.jpg|thumb|left|Manchu wrestlers competed in front of Qianlong Emperor]] |

[[File:Banquets-at-a-frontier-fortress.jpg|thumb|left|Manchu wrestlers competed in front of Qianlong Emperor]] |

||

Manchu |

Manchu wrestling ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᠪᡠᡴᡠ}}|v=buku}}) <ref name="摔跤史118" >{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=118}}</ref> is also an important martial art of the Manchu people.<ref name="摔跤史142" >{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=142}}</ref> Buku, meaning "wrestling" or "man of unusual strength" in Manchu, was originally from a Mongolian word, “[[Mongolian wrestling|bökh]]”.<ref name="摔跤史118" /> The history of Manchu wrestling can be traced back to Jurchen wrestling in the Jin Dynasty which was originally from Khitan wrestling; it was very similar to Mongolian wrestling.<ref>{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=120}}</ref> In the [[Yuan Dynasty]], the Jurchens who lived in northeast China adopted Mongol culture including wrestling, bökh.<ref>{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=119}}</ref> In the latter Jin and early Qing period, rulers encouraged the populace, including aristocrats, to practise buku as a feature of military training.<ref>{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=121}}</ref> At the time, Mongol wrestlers were the most famous and powerful. By the Chongde period, Manchus had developed their own well-trained wrestlers<ref>{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=123}}</ref> and, a century later, in the Qianlong period, they surpassed Mongol wreslers.<ref>{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=137}}</ref> The Qing court established the "Shan Pu Battalion" and chose 200 fine wrestlers divided into three levels. Manchu wrestling moves can be found in today's Chinese wrestling, [[Shuai jiao]], which is its most important part.<ref>{{harvnb|Jin|Kaihe|2006|p=153}}</ref> Among many branches, Beijing wrestling adopted most Manchu wrestling moves.<ref>[http://epaper.qingdaonews.com/html/qdwb/20120306/qdwb386565.html Qingdao Evening News: Different Branches of Shuaijiao (simplified Chinese)]</ref> |

||

====Falconry==== |

====Falconry==== |

||

| Line 1,620: | Line 1,615: | ||

====Ice skating==== |

====Ice skating==== |

||

[[File:在中南海公园滑冰的吴桐轩老人.jpg|thumb|left|1930s, Wu Tongxuan skates in Zhongnanhai Park]] |

[[File:在中南海公园滑冰的吴桐轩老人.jpg|thumb|left|1930s, Wu Tongxuan skates in Zhongnanhai Park]] |

||

Ice |

Ice skating ({{manchu|m={{MongolUnicode|ᠨᡳᠰᡠᠮᡝ<br>ᡝᡶᡳᡵᡝ<br>ᡝᡶᡳᠨ}}|v=nisume efime efin}}) is another Manchu pastime. Emperor Qianlong called it “national custom”.<ref>[http://news.xinhuanet.com/edu/2012-08/08/c_123551557.htm Xinhua: How Did Chinese Emperors Award Athletes? (simplified Chinese)]</ref> It is one of the most important winter events of the Qing royal household,<ref name="中新网冰嬉" >[http://www.chinanews.com/cul/news/2010/01-20/2083099.shtml China News:Qianlong Emperor made Ice Skating a National Custom (simplified Chinese)]</ref> performed by "Eight Banner Ice Skating Battalion" (八旗冰鞋营)<ref name="中新网冰嬉" /> which was a special force trained to do battle on icy terrain.<ref name="中新网冰嬉" /> The battalion consisted of 1600 soldiers. In the [[Jiaqing]] period, it was reduced to 500 soldiers and transferred to the Jing Jie Battalion (精捷营) originally, literally meaning "chosen agile battalion"</ref><ref name="中新网冰嬉" />。 |

||

In 1930s-1940s, there was a famous Manchu skater in Beijing whose name was Wu Tongxuan, from the Uya clan and one of the royal household skaters in Empress Dowager Cixi's reign.<ref name="满网滑冰老人" >[http://www.imanchu.com/a/people/200801/2577.html Manchu Old Man Skaters in Beijing (simplified Chinese)]</ref> He frequently appeared in many of Beijing's skating rinks.<ref name="满网滑冰老人" /> Nowadays, there are still Manchu figure skaters of which world champions [[Zhao Hongbo]] and [[Tong Jian]] are the pre-eminent examples. |

In 1930s-1940s, there was a famous Manchu skater in Beijing whose name was Wu Tongxuan, from the Uya clan and one of the royal household skaters in Empress Dowager Cixi's reign.<ref name="满网滑冰老人" >[http://www.imanchu.com/a/people/200801/2577.html Manchu Old Man Skaters in Beijing (simplified Chinese)]</ref> He frequently appeared in many of Beijing's skating rinks.<ref name="满网滑冰老人" /> Nowadays, there are still Manchu figure skaters of which world champions [[Zhao Hongbo]] and [[Tong Jian]] are the pre-eminent examples. |

||

| Line 1,630: | Line 1,625: | ||

*'''Day of running out of food''' (绝粮日):On every August 26 of lunar calendar. It is said that once [[Nurhaci]] and his troops were in a battle with enemies and almost running out of food. The villagers who lived near the battlefield heard the emergency and came to help. There was no tableware on the battlefield. They had to use [[perilla]] leaves to wrap the rice. Afterwards, they won the battle. So later generations could remember this hardship, Nurhaci made this day the "day of running out of food". Traditionally on this day, Manchu people usually eat perilla or [[Chinese cabbage|cabbage]] wraps with rice, scrambled eggs, beef or pork.<ref>[http://manchu.library.nenu.edu.cn/webcache/lishiwenhua/manzufengsu/201012/14-6518.html The Day of Running Out of Food (simplified Chinese)]</ref>。 |

*'''Day of running out of food''' (绝粮日):On every August 26 of lunar calendar. It is said that once [[Nurhaci]] and his troops were in a battle with enemies and almost running out of food. The villagers who lived near the battlefield heard the emergency and came to help. There was no tableware on the battlefield. They had to use [[perilla]] leaves to wrap the rice. Afterwards, they won the battle. So later generations could remember this hardship, Nurhaci made this day the "day of running out of food". Traditionally on this day, Manchu people usually eat perilla or [[Chinese cabbage|cabbage]] wraps with rice, scrambled eggs, beef or pork.<ref>[http://manchu.library.nenu.edu.cn/webcache/lishiwenhua/manzufengsu/201012/14-6518.html The Day of Running Out of Food (simplified Chinese)]</ref>。 |

||

*'''Banjin Inenggi''' ({{MongolUnicode|ᠪᠠᠨᠵᡳᠨ<br>ᡳᠨᡝᠩᡤᡳ}}): the anniversary of the name creation of Manchu in October 13 of lunar calendar.<ref name="明亡清兴六十年49"/> This day in 1635, Qing Taizong Emperor, Hong Taiji, changed the ethnic name from |

*'''Banjin Inenggi''' ({{MongolUnicode|ᠪᠠᠨᠵᡳᠨ<br>ᡳᠨᡝᠩᡤᡳ}}): the anniversary of the name creation of Manchu in October 13 of lunar calendar.<ref name="明亡清兴六十年49"/> This day in 1635, Qing Taizong Emperor, Hong Taiji, changed the ethnic name from Jurchen to Manchu.<ref name="太宗实录满洲"/><ref>[http://www.manchus.cn/plus/view.php?aid=1013 the Origin of Banjin Inenggi (simplified Chinese)]</ref> |

||

===Literature=== |

===Literature=== |

||

| Line 1,684: | Line 1,679: | ||

*{{Cite book|first=|last=Anonymous|title=满文老档 (Old Manchu Archive)|publisher=Zhonghua Book Company |year=1990|isbn=9787101005875|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/4106450/|ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|first=|last=Anonymous|title=满文老档 (Old Manchu Archive)|publisher=Zhonghua Book Company |year=1990|isbn=9787101005875|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/4106450/|ref=harv}} |

||

*{{Cite book|first=|last=Anonymous|title=竹书纪年校正, 光绪五年刻本 (Zhu Shu Ji Nian, 1879 Edition)|publisher= |year=1879|isbn=|url=http://ishare.iask.sina.com.cn/f/19291884.html|ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|first=|last=Anonymous|title=竹书纪年校正, 光绪五年刻本 (Zhu Shu Ji Nian, 1879 Edition)|publisher= |year=1879|isbn=|url=http://ishare.iask.sina.com.cn/f/19291884.html|ref=harv}} |

||

*{{Cite book|first=Jiaji|last=Du|title=清朝简史 (Brief History of Qing Dynasty)|publisher=Fujian People's Publishing House|year=1997|isbn=9787211027163|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/1582762/|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|first=|last=Fuge|title=听雨丛谈 (Miscellaneous Discussions Whilst Listening To The Rain)|publisher=Zhonghua Book Company |year=1984|isbn=978-7-101-01698-7|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/1042233/|ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|first=|last=Fuge|title=听雨丛谈 (Miscellaneous Discussions Whilst Listening To The Rain)|publisher=Zhonghua Book Company |year=1984|isbn=978-7-101-01698-7|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/1042233/|ref=harv}} |

||

*{{Cite book|first=Hehong|last=Gao|title=满族说部传承研究 (The Research of Manchu Ulabun)|publisher=China Social Sciences Pres|year=2011|isbn=9787500497127|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/6793307/|ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|first=Hehong|last=Gao|title=满族说部传承研究 (The Research of Manchu Ulabun)|publisher=China Social Sciences Pres|year=2011|isbn=9787500497127|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/6793307/|ref=harv}} |

||

| Line 1,705: | Line 1,701: | ||

*{{Cite book|first=Yunying|last=Wang|title=清代满族服饰 (Manchu Traditional Clothes of Qing Dynasty)|publisher=Liaoning Nationality Publishing House|year=1985|isbn=|url=http://book.kongfz.com/113/144899163/|ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|first=Yunying|last=Wang|title=清代满族服饰 (Manchu Traditional Clothes of Qing Dynasty)|publisher=Liaoning Nationality Publishing House|year=1985|isbn=|url=http://book.kongfz.com/113/144899163/|ref=harv}} |

||

*{{Cite book|last=Writing Group of Manchu Brief History|title=满族简史 (Brief History of Manchus)|publisher=National Publishing House|year=2009|isbn=9787105087259|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/3700230/ |ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|last=Writing Group of Manchu Brief History|title=满族简史 (Brief History of Manchus)|publisher=National Publishing House|year=2009|isbn=9787105087259|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/3700230/ |ref=harv}} |

||

*{{Cite book|first=Chongnian|last=Yan|title=努尔哈赤传 (the Biography of Nurhaci)|publisher=Beijing Publishing House|year=2006|isbn=9787200016598|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/1834831/|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|first=Chongnian|last=Yan|title=明亡清兴六十年 彩图珍藏版 (60 Years History of the Perishing Ming and Rising Qing, Valuable Colored Picture Edition)|publisher=Zhonghua Book Compary|year=2008|isbn=9787101059472|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/2359481/|ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|first=Chongnian|last=Yan|title=明亡清兴六十年 彩图珍藏版 (60 Years History of the Perishing Ming and Rising Qing, Valuable Colored Picture Edition)|publisher=Zhonghua Book Compary|year=2008|isbn=9787101059472|url=http://book.douban.com/subject/2359481/|ref=harv}} |

||

*{{Cite book|first=Min-hwan|last=Yi|title=清初史料丛刊第八、九种:栅中日录校释、建州见闻录校释 (The Collection of Early Qing's Historical Sources, Vol.8 & 9: Records in the Fence; Witness Records of Jianzhou)|publisher=History Department of Liaoning University|year=1978|isbn=|url=http://books.google.com/books/about/%E6%B8%85%E5%88%9D%E5%8F%B2%E6%96%99%E4%B8%9B%E5%88%8A%E7%AC%AC%E5%85%AB_%E4%B9%9D%E7%A7%8D.html?id=gtbjtgAACAAJ|ref=harv}} |

*{{Cite book|first=Min-hwan|last=Yi|title=清初史料丛刊第八、九种:栅中日录校释、建州见闻录校释 (The Collection of Early Qing's Historical Sources, Vol.8 & 9: Records in the Fence; Witness Records of Jianzhou)|publisher=History Department of Liaoning University|year=1978|isbn=|url=http://books.google.com/books/about/%E6%B8%85%E5%88%9D%E5%8F%B2%E6%96%99%E4%B8%9B%E5%88%8A%E7%AC%AC%E5%85%AB_%E4%B9%9D%E7%A7%8D.html?id=gtbjtgAACAAJ|ref=harv}} |

||

Revision as of 07:31, 14 November 2012

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10,430,000 0.15% of global human population (estimate) 10,410,585[1] 0.77% of China's population (estimate) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 10,410,585[1] | |

| ↳ | >288[2] |

| 12,000[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Standard Chinese • Manchu | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism • Buddhism • Chinese folklore • Christianity, also many are Atheists or Agnostics[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Evenks • Nanai • Oroqen • Udege • Sibe and other Tungusic peoples | |

The Manchus[note 1] (Manchu: ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ, Möllendorff: manju; simplified Chinese: 满族; traditional Chinese: 滿族; pinyin: Mǎnzú) are members of an indigenous people of Manchuria[9] also known as red tasseled Manchus (Manchu: ᡶᡠᠯᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ

ᠰᠣᡵᠰᠣᠨ

ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ, Möllendorff: fulgiyan sorson manju; 红缨满洲) because of their traditional hat ornaments.[10][11][note 2] They are the largest branch of the Tungusic peoples and are chiefly distributed throughout China, forming the fourth largest ethnic group and the third largest ethnic minority group in that country.[1]

Manchus conquered China and established the Qing Dynasty in 1644. The dynasty came to an end in 1912 when the country became a republic. As a result of the conquest in the 17th century, almost all the Manchus followed regent prince Dorgon (ᡩᠣᡵᡤᠣᠨ) and Shunzhi Emperor to their new capital Beijing (Manchu: ᠪᡝᡤᡳᠩ, Möllendorff: beging[13]) and mainly settled down there.[14][15] Few of them were sent to other places of mainland China, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet as garrisons.[15] There were only 1524 Banner soldiers left in Manchuria at the time.[16] After the border conflicts with Russians, Qing's emperors started to realize the strategic importance of Manchuria and gradually sent Manchus back to where they originally came from.[14] However, during the period of Qing, Beijing was always the only focal point of Manchus in political, economic and cultural aspects. Yongzheng Emperor said, "Garrisons are the places of stationed works, Beijing is their homeland."[17] After the fall of Qing Empire, especially the establishments of Manchu autonomous areas by PRC government, Manchuria became significant to Manchus again.

Nowadays, Manchu residents can be found in 31 Chinese provincal regions. Among them, Liaoning has the largest population and Hebei, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Inner Mongolia and Beijing has over 100,000 Manchu residents. About half of the population live in Liaoning province and one-fifth in Hebei province. There are a number of Manchu autonomous counties in both provinces.

History

Origins and early history

The Manchus are descended from the Jurchen people who earlier established the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) in China[18][19][20] but as early as the semi-mythological chronicles of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors there is mention of the Sushen,[21][22][23][24] a Tungusic people from the northern Manchurian region of North East Asia, who paid bows and arrows as tribute to Shun[25] and later to Zhou.[26] The cognates Sushen or Jichen (稷真) again appear in the Shan Hai Jing and Book of Wei during the dynastic era referring to Tungusic Mohe tribes of the far Northeast.[27] In the 10th century AD the term Jurchen first appeared in documents of the late Tang dynasty in reference to the ethnic-Goguryeo state of Balhae.

Following the fall of Balhae the Jurchens were vassals of the Liao dynasty. In the year of 1114, Wanyan Aguda united the Jurchen tribes and established the Jin dynasty.[28] His brother and successor, Wanyan Wuqimai destroyed Liao and Northern Song and established the Jin Dynasty.[29] During the Jin Dynasty, first Jurchen scripts came into use in 1120s. It was mainly derived from Khitan script.[28]

In 1206, the Mongols who were vassal to Jurchens rose in Mongolia. Their leader, Genghis Khan, led the Mongol troops to fight against Jurchens. Jin dynasty could not withstand Mongols' attack and was finally defeated by Ögedei Khan in 1234.[30] Under the Mongols' control, Jurchens were mainly divided in two groups and treated differently: the ones who were born and raised in North China and fluent in Chinese were considered as Chinese people (Han); but the people who were born and raised in Jurchen's homeland (Manchuria) without a Chinese-speaking abilities were treated as Mongols politically.[31] Since then, the Jurchens of North China increasingly merged with Han Chinese and the ones living in their homeland started to be Mongolized.[32] They adopted Mongolian customs, names[note 3] and learning Mongolian language. Less Jurchens could recognize their own scripts since then.

The Mongol domination of China was replaced by Ming Dynasty in 1368. In 1387, Ming defeated Nahacu's Mongol resisting forces who settled in Haixi area[33] and began to summon the Jurchen tribes to pay tribute[34] At the time, some Jurchen tribes were vassal to Joseon dynasty of Korea such as Odoli and Huligai.[35] Their elites served in Korean royal bodyguard.[36] However, their relationship discontinued by Ming, because Ming was planning to make Jurchens their protection of border. Korea had to allow it since itself was in Ming's tribute system.[36] In 1403, Ahacu, chieftain of Huligai, paid tribute to Yongle Emperor of Ming. Soon after that, Möngke Temür, chieftain of Odoli, went to tribute from Korea, too. Yi Seong-gye, the Taejo of Joseon requested Ming to send Möngke Temür back but rejected.[37] Since then, more and more Jurchen tribes presented tribute to Ming in succession.[34] They were divided in 384 guards by Ming.[36]

In 1449, Mongol taishi Esen assulted Ming Dynasty and captured Zhengtong Emperor in Tumu. Some Jurchen guards in Jianzhou and Haixi coorperated with Esen's action,[38] but more were also attacked by the Mongol invasion. A large number of Jurchen chieftains lost their hereditary certificate which was granted by Ming.[39] They had to present tribute as secretariats (中书舍人) with much less award from Ming court than they were heads of guards which was not joyful to the them.[39] Since then, Jurchen guards gradually went out of Ming's control.[39] Some tribal leaders even publically plundered Ming's area, such as Cungšan[note 4] and Wang Gao. Approximately in this period, the Jurchen scripts was offcially abandoned.[41] More Jurchens adopted Mongolian as their writting language and the less used Chinese.[42]

Manchu reign of China

A century after the chaos started in Jurchen's land, Nurhaci, a chieftain of Jianzhou Left Guard, started his ambition as a revenge of Ming's manslaughter of his grandfather and father in 1583.[43] He reunified Jurchen tribes, established a military system called "Eight Banners" to organized Jurchen soldiers as "Bannermen" and ordered his scholar Erdeni and minister Gagai to create a new Jurchen script (later known as Manchu script) by referencing traditional Mongolian alphabet.[44]

In 1603, Nurhaci was recognized as Sure Kundulen Khan (Manchu: ᠰᡠᡵᡝ

ᡴᡠᠨᡩᡠᠯᡝᠨ

ᡥᠠᠨ, Möllendorff: sure kundulen han, "wise and respected khan") by his Khalkha Mongol allies.[45] 13 years later (1616), he publically throned and proclaimed himself Genggiyen Khan (Manchu: ᡤᡝᠩᡤᡳᠶᡝᠨ

ᡥᠠᠨ, Möllendorff: genggiyen han, "bright khan") of Later Jin Dynasty (Manchu: ᠠᠮᠠᡤᠠ

ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ, Möllendorff: amaga aisin gurun[note 5], 后金) and then eventually launched his attack on Ming Dynasty.[45] Nurhaci moved the capital to Mukden after his conquest of Liaodong.[47] In 1635, his son and successor Hong Taiji changed the ethnic group Jurchen (Manchu: ᠵᡠᡧᡝᠨ, Möllendorff: jušen) to Manchu.[48] A year later, Hong Taiji proclaimed himself the emperor of Qing Dynasty (Manchu: ᡩᠠᡳᠴᡳᠩ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ, Möllendorff: daicing gurun[note 6]).[50] With general Wu Sangui's support, Qing Empire made a breakthrough to mainland China in 1644. After defeated Li Zicheng, they moved the capital to Beijing in the same year.[51]

While the Manchu ruling elite at the Beijing imperial court and posts of authority throughout China increasingly adopted Chinese culture, the Qing imperial government viewed the Manchu communities (as well as those of various tribal people) in Manchuria as a place where traditional Manchu virtues could be preserved, and as a reservoir of military manpower fully dedicated to the regime.[52] The emperors tried to protect the traditional way of life of the Manchus (as well as various tribal people) in the central and northern Manchuria by a variety of means, in particular, restricting the migration of Chinese colonists to the region. This ideal, however, had to be balanced with practical needs, such as maintaining the defense against the Russians and the Mongols, supplying government farms with skilled work force, and running trade in the region's products, which resulted in a continuous trickle of Chinese convicts, workers, and merchants to the north-east.[53]

However, this policy of artificially isolating the Manchus of the north-east from the rest of China could not last forever. In the 1850s, large numbers of the Manchu bannermen were sent to central China to fight the Taiping rebels. (For example, just the Heilongjiang province - which at the time included only the northern part of today's Heilongjiang - contributed 67,730 bannermen to the campaign, of which merely 10-20% survived).[54] Those few who returned were demoralized and often exposed to opium addiction.[55] In 1860, in the aftermath of the loss of the "Outer Manchuria", and with the imperial and provincial governments in deep financial trouble, parts of Manchuria became officially open to Chinese settlement;[56] within a few decades, the Manchus became a minority in most of Manchuria's districts.

Modern days

As the end of the Qing Dynasty approached, Manchus were portrayed as outside colonizers by Chinese nationalists such as Sun Yat-Sen, even though the Republican revolution he brought about was supported by many reform-minded Manchu officials and military officers.[57] This portrayal dissipated somewhat after the 1911 revolution as the new Republic of China now sought to include Manchus within its national identity.[58]

By the early years of the Republic of China, very few areas of China still had traditional Manchu populations. Among the few regions where such comparatively traditional communities could be found, and the Manchu language was still widely spoken, were the Aigun District (whose folkways the Russian ethnographer S. M. Shirokogoroff studied in 1915-1916) and the Tsitsihar District of Heilongjiang Province.[59] The Xibo also maintained their identity at their Xinjiang outpost.

Until 1924, the government continued to pay stipends to Manchu bannermen; however, many cut their links with their banners and took on Han-style names in shame and to avoid persecution.[60] The official total of Manchu fell by more than half during this period, as they refused to admit to their ethnicity when asked by government officials or other outsiders.[61]

In 1931, as a follow-up action of Mukden Incident, Manchukuo, a puppet state in Manchuria, was created by Imperial Japan which was nominally ruled by the deposed Emperor Puyi. Although the nation's name was related to Manchus, it is actually a complete new country for all the ethnicities in Manchuria[62] and was opposed by many Manchus who fought against Japan in World War II, too.[63] Manchukuo had a majority Han population, largely due to internal migration from China. The country was abolished at the end of the World War after the Soviet invasion of Manchuria, with its territory incorporated again into China.

The People's Republic of China recognised the Manchu as one of the country's official minorities in 1952.[64] In the 1953 census, 2.5 million people identified themselves as Manchu.[65] The Communist government also attempted to improve the treatment of Manchu people; some Manchu people who had hidden their ancestry during the period of KMT rule thus became more comfortable to reveal their ancestry, such as the writer Lao She, who began to include Manchu characters in his fictional works in the 1950s (in contrast to his earlier works which had none).[66] Between 1982 and 1990, the official count of Manchu people more than doubled from 4,299,159 to 9,821,180, making them China's fastest-growing ethnic minority.[67] In fact, however, this growth was not due to natural increase, but instead people formerly registered as Han applying for official recognition as Manchu.[68]

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in Manchu culture among both ethnic Manchus and Han.[69]

Etymology of the ethnic name

The actual etymology of the ethnic name "Manju" is debatable.[70] According to Qing Dynasty's official historical record, the Researches on Manchu Origins, the ethnic name came from Mañjuśrī.[71] Qianlong Emperor also supported the point of view and even made few poems about it.[72]

Meng Sen, a famous scholar of Qing study, agreed, too. On the other hand, he thought the name "Manchu" is also related to Li Manzhu, the chieftain of Jianzhou Jurchen.[73] It was just the most respectful appellation in the society of Jianzhou Jurchens in Meng's mind.[74]

Another scholar, Chang Shan, thinks Manju is a compound word. "Man" was from the word "mangga" (ᠮᠠᠩᡤᠠ) which means strong and "ju" (ᠵᡠ) means arrow. So Manju actually means "intrepid arrow".[75]

There are other hypothesis, such as Fu Sinian's "etymology of Jianzhou"; Zhang Binglin's "etymology of Jianzhou"; Isamura Sanjiro's "etymology of Wuji and Mohe"; Sun Wenliang's "etymology of Manzhe"; "etymology of mangu(n) river" and so on.[76][77]

Population

Mainland China

Most Manchu people now live in Mainland China with a population of 10,410,585[1] Which is 9.28% of ethnic minorities and 0.77% of China's total population.[1] Among the provincial regions, there are 3 provinces, Liaoning and Hebei, which have over 1,000,000 Manchu residents.[1] Liaoning has 5,336,895 Manchu residents which is 51.26% of Manchu population and 12.20% provincial population; Hebei has 2,118,711 which is 20.35% of Manchu people and 70.80% of provincial ethnic minorites.[1] Manchu is the largest ethnic minority in Liaoning, Hebei, Heilongjiang and Beijing; 2nd largest in Jilin, Inner Mongolia, Tianjin, Tianjin, Ningxia, Shaanxi and Shanxi and 3rd largest in Henan, Shandong and Anhui,.[1]

Distribution

| Rank |

Region |

Total Population |

Manchu |

Percentage in Manchu Population |

Percentage in the Population of Ethnic Minorities(%) |

Regional Percentage of Population |

Regional Rank of Ethnic Population |

| Total | 1,335,110,869 | 10,410,585 | 100 | 9.28 | 0.77 | ||

| Total (in all 31 provincial regions) |

1,332,810,869 | 10,387,958 | 99.83 | 9.28 | 0.78 | ||

| G1 | Northeast | 109,513,129 | 6,951,280 | 66.77 | 68.13 | 6.35 | |

| G2 | North | 164,823,663 | 3,002,873 | 28.84 | 32.38 | 1.82 | |

| G3 | East | 392,862,229 | 122,861 | 1.18 | 3.11 | 0.03 | |

| G4 | South Central | 375,984,133 | 120,424 | 1.16 | 0.39 | 0.03 | |

| G5 | Northwest | 96,646,530 | 82,135 | 0.79 | 0.40 | 0.08 | |

| G6 | Southwest | 192,981,185 | 57,785 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.03 | |

| 1 | Liaoning | 43,746,323 | 5,336,895 | 51.26 | 80.34 | 12.20 | 2nd |

| 2 | Hebei | 71,854,210 | 2,118,711 | 20.35 | 70.80 | 2.95 | 2nd |

| 3 | Jilin | 27,452,815 | 866,365 | 8.32 | 39.64 | 3.16 | 3rd |

| 4 | Heilongjiang | 38,313,991 | 748,020 | 7.19 | 54.41 | 1.95 | 2nd |

| 5 | Inner Mongolia | 24,706,291 | 452,765 | 4.35 | 8.96 | 2.14 | 3rd |

| 6 | Beijing | 19,612,368 | 336,032 | 3.23 | 41.94 | 1.71 | 2nd |

| 7 | Tianjin | 12,938,693 | 83,624 | 0.80 | 25.23 | 0.65 | 3rd |

| 8 | Henan | 94,029,939 | 55,493 | 0.53 | 4.95 | 0.06 | 4th |

| 9 | Shandong | 95,792,719 | 46,521 | 0.45 | 6.41 | 0.05 | 4th |

| 10 | Guangdong | 104,320,459 | 29,557 | 0.28 | 1.43 | 0.03 | 9th |

| 11 | Shanghai | 23,019,196 | 25,165 | 0.24 | 9.11 | 0.11 | 5th |

| 12 | Ningxia | 6,301,350 | 24,902 | 0.24 | 1.12 | 0.40 | 3rd |

| 13 | Guizhou | 34,748,556 | 23,086 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 18th |

| 14 | Xinjiang | 21,815,815 | 18,707 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 10th |

| 15 | Jiangsu | 78,660,941 | 18,074 | 0.17 | 4.70 | 0.02 | 7th |

| 16 | Shaanxi | 37,327,379 | 16,291 | 0.16 | 8.59 | 0.04 | 3rd |

| 17 | Sichuan | 80,417,528 | 15,920 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 10th |

| 18 | Gansu | 25,575,263 | 14,206 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 7th |

| 19 | Yunnan | 45,966,766 | 13,490 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 24th |

| 20 | Hubei | 57,237,727 | 12,899 | 0.12 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 6th |

| 21 | Shanxi | 25,712,101 | 11,741 | 0.11 | 12.54 | 0.05 | 3rd |

| 22 | Zhejiang | 54,426,891 | 11,271 | 0.11 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 13th |

| 23 | Guangxi | 46,023,761 | 11,159 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 12th |

| 24 | Anhui | 59,500,468 | 8,516 | 0.08 | 2.15 | 0.01 | 4th |

| 25 | Fujian | 36,894,217 | 8,372 | 0.08 | 1.05 | 0.02 | 10th |

| 26 | Qinghai | 5,626,723 | 8,029 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 7th |

| 27 | Hunan | 65,700,762 | 7,566 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 9th |

| 28 | Jiangxi | 44,567,797 | 4,942 | 0.05 | 2.95 | 0.01 | 6th |

| 29 | Chongqing | 28,846,170 | 4,571 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 7th |

| 30 | Hainan | 8,671,485 | 3,750 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 8th |

| 31 | Tibet | 3,002,165 | 718 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 11th |

| Active Servicemen | 2,300,000 | 22,627 | 0.24 | 23.46 | 1.05 | 2nd |

Manchu autonomous regions

| Manchu Ethnic Town/Township |

Province Autonomous area Municipality |

City Prefecture |

County |

| Paifang Hui and Manchu Ethnic Township | Anhui | Hefei | Feidong |

| Labagoumen Manchu Ethnic Township | Beijing | N/A | Huairou |

| Changshaoying Manchu Ethnic Township | Beijing | N/A | Huairou |

| Huangni Yi, Miao and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Dafang |

| Jinpo Miao, Yi and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Qianxi |

| Anluo Miao, Yi and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Jinsha |

| Xinhua Miao, Yi and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Jinsha |

| Tangquan Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Tangshan | Zunhua |

| Xixiaying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Tangshan | Zunhua |

| Dongling Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Tangshan | Zunhua |

| Lingyunce Manchu and Hui Ethnic Township | Hebei | Baoding | Yi |

| Loucun Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Baoding | Laishui |

| Daweihe Hui and Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Langfang | Wen'an |

| Pingfang Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Anchungou Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Wudaoyingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Zhengchang Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Mayingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Fujiadianzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Xidi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Xiaoying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Datun Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Xigou Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Gangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Chengde |

| Liangjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Chengde |

| Bagualing Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Xinglong |

| Nantianmen Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Xinglong |

| Yinjiaying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Miaozigou Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Badaying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Taipingzhuang Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Jiutun Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Xi'achao Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Baihugou Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Liuxi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Qijiadai Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Pingfang Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Maolangou Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Xuzhangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Nanwushijia Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Guozhangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Hongqi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Nangang |

| Xingfu Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Lequn Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Tongxin Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Xiqin Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Gongzheng Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Lianxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Xinxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Qingling Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Nongfeng Manchu and Xibe Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Yuejin Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Lalin Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Hongqi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Niujia Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Yingchengzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Shuangqiaozi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Liaodian Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Acheng |

| Shuishiying Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Qiqihar | Ang'angxi |

| Youyi Daur, Kirgiz and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Qiqihar | Fuyu |

| Taha Manchu and Daur Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Qiqihar | Fuyu |

| Jiangnan Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Mudanjiang | Ning'an |

| Chengdong Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Mudanjiang | Ning'an |

| Sijiazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Heihe | Aihui |

| Yanjiang Daur and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Heihe | Sunwu |

| Suisheng Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Beilin |

| Yong'an Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Beilin |

| Hongqi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Beilin |

| Huiqi Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Wangkui |

| Xiangbai Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Wangkui |

| Lingshan Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Wangkui |

| Fuxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Hegang | Suibin |

| Chengfu Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Shuangyashan | Youyi |

| Longshan Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Siping | Gongzhuling |

| Ershijiazi Manchu Ethnic Town | Jilin | Siping | Gongzhuling |

| Sanjiazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Yanbian | Hunchun |

| Yangpao Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Yanbian | Hunchun |

| Wulajie Manchu Ethnic Town | Jilin | Jilin City | Longtan |

| Dakouqin Manchu Ethnic Town | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Liangjiazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Jinjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Tuchengzi Manchu and Korean Ethnic Township | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Jindou Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Tonghua | Tonghua County |

| Daquanyuan Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Tonghua | Tonghua County |

| Xiaoyang Manchu and Korean Ethnic Township | Jilin | Tonghua | Meihekou |

| Sanhe Manchu and Korean Ethnic Township | Jilin | Liaoyuan | Dongfeng County |

| Mantang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Dongling |

| Liushutun Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Shajintai Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Dongsheng Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Liangguantun Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Shihe Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Dalian | Jinzhou |

| Qidingshan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Jinzhou |

| Taling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Gaoling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Guiyunhua Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Sanjiashan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Yangjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Wafangdian |

| Santai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Wafangdian |

| Laohutun Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Wafangdian |

| Dagushan Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Anshan | Qianshan |

| Songsantaizi Korean and Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Anshan | Qianshan |

| Lagu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Fushun | Fushun County |

| Tangtu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Fushun | Fushun County |

| Sishanling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Benxi | Nanfen |

| Xiamatang Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Benxi | Nanfen |

| Huolianzhai Hui and Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Benxi | Xihu |

| Helong Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dandong | Donggang |

| Longwangmiao Manchu and Xibe Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Dandong | Donggang |

| Juliangtun Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Jiudaoling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Dizangsi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Hongqiangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Liulonggou Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Shaohuyingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Dadingpu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Toutai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Toudaohe Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Chefang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Wuliangdian Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Baichanmen Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Heishan |

| Zhen'an Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Heishan |

| Wendilou Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Linghai |

| Youwei Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Linghai |

| East Liujiazi Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Fuxin | Zhangwu |

| West Liujiazi Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Fuxin | Zhangwu |

| Jidongyu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Liaoyang | Liaoyang County |

| Shuiquan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Liaoyang | Liaoyang County |

| Tianshui Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Liaoyang | Liaoyang County |

| Quantou Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Tieling | Changtu County |

| Babaotun Manchu, Xibe and Korean Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Huangqizhai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Shangfeidi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Xiafeidi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Linfeng Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Baiqizhai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Tieling County |

| Hengdaohezi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Tieling County |

| Chengping Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Dexing Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Helong Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Jinxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Mingde Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Songshu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Yingcheng Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Xipingpo Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Dawangmiao Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Fanjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Gaodianzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Gejia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Huangdi Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Huangjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Kuanbang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Mingshui Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Shahe Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Wanghu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Xiaozhuangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Yejia Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Gaotai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Baita Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Caozhuang Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Dazhai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Dongxinzhuang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Gaojialing Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Guojia Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Haibin Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Hongyazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Jianjin Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Jianchang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Jiumen Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Liutaizi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Nandashan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Shahousuo Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Wanghai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Weiping Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Wenjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Yang'an Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Yaowangmiao Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Yuantaizi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Erdaowanzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Jianchang |

| Xintaimen Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Lianshan |

| Manzutun Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Hinggan | Horqin Right Front Banner |

| Guanjiayingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Chifeng | Songshan |

| Shijia Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Chifeng | Harqin Banner |

| Caonian Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Ulanqab | Liangcheng |

| Sungezhuang Manchu Ethnic Township | Tianjin | N/A | Ji |

Other areas

Manchu people can be found living outside mainland China. There are approximately 12,000 Manchus now in Taiwan. Most of them moved to Taiwan with the ROC government in 1949. Puru, a famous painter, calligrapher and also the founder of the Manchu Association of Republic of China, was a typical example.[3] There are also Manchus who settled in the United States and Japan, such as John Fugh, Garry Guan and Fukunaga Kosē.

Culture

Language and alphabet

Language

Manchu is a branch of the Tungusic languages and has many dialects:

- Standard Manchu: Standard Manchu originates from the accent of Jianzhou Jurchens.[78] It was standardized by the Qianlong Emperor under his reign.[79] During the Qing period, Manchus at court were required to speak Standard Manchu[80] or face the emperor's reprimand.[80] This applied equally to the palace presbyter of shamanic fete when performing sacrifice.[80]。

- Beijing dialect: The Manchus who lived in Beijing were not only Jianzhou Jurchens, but also Haixi Jurchens and Yeren Jurchens. Over time, the mingling of their accents produced Beijing dialect (京语). Beijing dialect is really close to Standard Manchu[81]。

- Mukden-South Manchurian dialect:Mukden-South Manchurian dialect (盛京南满语), aka, "Mukden-Girin dialect" (盛京吉林语) was originally spoken by the Manchus who lived in Liaoning and the western and southern areas of Jilin, having an accent very close to the Xibe language spoken by the Xibes living in Qapqal.[82]

There are also Ningguta, Alcuka dialects, etc., of Manchu which have their own particular characteristics.[83]

Alphabet

Jurchens, ancestors of the Manchu, had created Jurchen script in the Jin Dynasty. After Jin collapsed, Jurchen script was gradually lost. In the Ming period, 60%-70% of Jurchens used Mongolian script to write letters and 30%-40% of Jurchens used Chinese characters.[42] This persisted until Nurhaci revolted against the Ming reign. Nurhaci considered it a major impediment that his people lacked a script of their own, so he commanded his scholars, Gagai and Eldeni, to create Manchu characters by reference to Mongolian scripts.[84] They dutifully complied with the Khan's order and created Manchu script, which is called "script without dots and circles" (Manchu: ᡨᠣᠩᡴᡳ

ᡶᡠᡴᠠ

ᠠᡴᡡ

ᡥᡝᡵᡤᡝᠨ, Möllendorff: tongki fuka akū hergen; 无圈点满文) or "old Manchu script" (老满文).[85] Due to its hurried creation, the script has its defects. Some vowels and consonants were difficult to distinguish.[86][87] Shortly afterwards, their successor Dahai used dots and circles to distinguish vowels, aspirated and non-aspirated consonants and thus completed the script. His achievement is called "script with dots and circles" or "new Manchu script".[88]

Current situation

After the 1800s, most Manchus had perfected Standard Chinese and the number who knew Manchu was dwindling.[89] Although the Qing emperors emphasized the importance of Manchu language again and again, the tide could not be turned. After the Qing collapsed, the Manchu language lost its status as a national language and its use officially in education ended. Manchus today generally speak Standard Chinese. The remaining skilled native Manchu speakers number less than 100,[90] most of whom are to be found in Sanjiazi ((Manchu: ᡳᠯᠠᠨ

ᠪᠣᠣ, Möllendorff: ilan boo), Heilongjiang Province.[91] In recent years, with the help of the governments in Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang, many schools started to have Manchu classes.[92][93][94] There are also Manchu volunteers in many places of China who freely teach Manchu in the desire to rescue of the language.[95][96][97][98] Thousands of non-Manchu speakers have learned the language through these measures.[99][100]

Names and naming practices

Family names

The history of Manchu family names is quite long. Fundamentally, it succeeds the Jurchen family name of the Jin Dynasty.[101] However, after the Mongols extinguished the Jurchen empire, Manchus started to adopt Mongol culture, including their custom of using only their given name till the end of the Qing Dynasty,[102] a practice confounding non-Manchus, leading them to conclude, erroneously, that they simply don't have family names.[103]

A Manchu family name usually has two portions: the first is "Mukūn" (ᠮᡠᡴᡡᠨ) which literally means "branch name"; the second, "Hala" (ᡥᠠᠯᠠ), represents the name of a person's clan.[104] According to the Book of the Eight Manchu Banners' Surname-Clans (八旗滿洲氏族通譜), there are 1,114 Manchu family names. Gūwalgiya, Niohuru, Šumulu, Tatara, Gioro, Nara are considered as "famous clans" (著姓) among Manchus.[105]

Given names

Manchus given names are distinctive. Generally, there are several forms, as below:

- bearing suffixes such as "-ngga", "-ngge" or "-nggo", meaning "having the quality of";[106][107]

- bearing the suffixes "-tai" or "-tu", meaning "having";[107][108]

- bearing the suffix, "-ju", "-boo";[107]

- numerals, such as Nadanju,[note 7] Susai,[note 8] Liošici[note 9] and Bašinu;[note 10][107][108]

- animal names, e.g. Dorgon.[106][107]

Current status

Nowadays, Manchus primarily use Chinese family and given names, but some still use a Manchu family name and Chinese given name,[note 11] a Chinese family name and Manchu given name[note 12] or both Manchu family and given names.[note 13]

Traditional garments

- Hats: Wearing hats is a part of Manchu traditional culture.[109] Conventionally, especially different from Han Chinese culture of "Starting to wear hats in 20 year-old" (二十始冠), Manchu people wear hats in all ages and seasons.[109] Manchu hats has formal and casual ones. Formal hats also have two different styles. One is straw hats wearing in spring and summer; another is warm hat wearing in fall and winter. Manchu casual hat is more known as "Mandarin hat" in English.[110]

- Robe: Sijigiyan(ᠰᡳᠵᡳᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ), the Manchu robe, is the most representative clothing of the Manchu people.[111] Modern Chinese female suit Cheongsam deverted from Manchu robe.[111]

- Surcoat: Manchu surcoat (马褂) was a military uniform of Eight banners army.[112] Since Kangxi period, surcoat got popular in third estate.[113] The Chinese suit "Tangzhuang" is directly deverted from it.

Manchus have many distinctive traditional accessories. Women traditionally wear 3 earrings in each ear,[114] a tradition that is maintained by many older Manchu women.[115] Manchu men also traditionally wear piercings, but they tend to only have one earring in their youth and do not continue to wear it as adults.[116]

The Manchu people also have traditional jewelry which evokes their past as hunters. The fergetun (ᡶᡝᡵᡤᡝᡨᡠᠨ), a thumb ring traditionally made out of reindeer bone, was worn to protect the thumbs of archers. After the Manchu conquest of China in 1644, the fergetun gradually became simply a form of jewelry, with the most valuable ones made in jade and ivory.[117]

-

Men's robe

-

Women's robe

-

Men's formal court robe

-

Women's formal court robe

-

Empress Wanrong dressed in women's formal court robe and sleeveless coat

-

Imperial concubines dressed in Manchu semiformal robes

-

Manchu noble ladies in robes

-

Men's surcoat

-

Men's short-sleeved surcoat

-

Hat

-

Women's traditional "3 earings" style

-

"Fergetun", Manchu thumb ring

Religion

The religions of the Manchus are diverse. Originally, Manchus, and their predecessors, were principally Shamanists. After the conquest of China in the 17th century, Manchus came into contact with Chinese culture. They were markedly influenced by Chinese folk religion and retained only some Shamanic customs. Buddhism and Christianity also had their impacts. Manchus are today mostly irreligious.[4]

Shamanism

Shamanism has a long history in Manchu civilization and influenced them tremendously over thousands of years. After the conquest of China in the 17th century, although Manchus widely adopted Chinese folk religion, Shamanic traditions can still be found in the aspects of soul worship, totem worship, belief in nightmares and apotheosis of philanthropists.[118] Since the Qing rulers considered religion as a method of controlling other powers such as Mongolians and Tibetans,[119] there was no privilege for Shamanism, their native religion. Apart from the Shamanic temples in the Qing palace, no temples erected for worship of Manchu gods could be found in Beijing.[119] Thus, the story of competition between Shamanists and Lamaists was oft heard in Manchuria but the Manchu emperor helped Lamaists to persecute Shamanists which led to their considerable frustration and dissatisfaction.[119]

Buddhism

Jurchens, the predecessors of the Manchus, were influenced by the Buddhism of Balhae, Goryeo, Khitan and Song in the 10-13th centuries,[120] so it was not something new to the rising Manchus in the 16-17th centuries. Qing emperors were always entitled "Buddha". They were regarded as Mañjuśrī in Tibetan Buddhism[74] and had high attainments.[120] However, Buddhism was used by rulers to control Mongolians and Tibetans; it was of little relevance to ordinary Manchus in the Qing Dynasty.[119]

Folklore

Manchus were affected by Chinese folk religions for most of the Qing Dynasty.[119] Save for ancestor worship, the gods they consecrated were virtually identical to those of the Han Chinese.[119] Guan Yu worship is a typical example. He was considered as the God Protector of the Nation and was sincerely worshipped by Manchus. They called him "Lord Guan" (关老爷). Uttering his name was taboo.[119] In addition, Manchus worshipped Cai Shen and The Kitchen god just as the Han Chinese did. The worship of Mongolian and Tibetan gods has also been reported.[119]

Christianity

There were Manchu Christians in the Qing Dynasty. In Yongzheng and Qianlong's era, Depei, the Hošo Jiyan Prince, was a Catholic whose baptismal name was "Joseph". His wife was also baptised and named “Maria”.[121] At the same time, the sons of Doro Beile Sunu were devout Catholics, too.[121][122] In the Jiaqing period, Tong Hengšan and Tong Lan were Catholic Manchu Bannermen.[121] These Manchu Christians were proselytized and persecuted by Qing emperors but they steadfastly refused to convert.[121] There were Manchu Christians in modern times, too, such as Ying Lianzhi, Lao She and Philip Fugh.

Traditional activities

Riding and archery