NATO: Difference between revisions

→External links: more accurate |

|||

| Line 498: | Line 498: | ||

{{NATO}} |

{{NATO}} |

||

{{Cold War}} |

{{Cold War}} |

||

{{War on Terrorism}} |

|||

[[Category:4-letter acronyms]] |

[[Category:4-letter acronyms]] |

||

Revision as of 20:30, 2 July 2006

| |

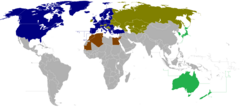

NATO countries are in blue | |

| Formation | April 4, 1949 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Brussels |

Membership | 26 member states |

Official language | English, French |

Secretary General | Jaap de Hoop Scheffer |

| Website | |

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, the Atlantic Alliance or the Western Alliance, is an international organisationTemplate:Fn for collective security established in 1949, in support of the North Atlantic Treaty signed in Washington, DC, on 4 April 1949. Its headquarters are located in Brussels[1], Belgium. Its other official name is the French equivalent, l'Organisation du Traité de l'Atlantique Nord (OTAN) (English and French being the two official languages of the organisation).

Purpose

The core of NATO is Article V of the North Atlantic Treaty, which states:

- The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all. Consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.

The Treaty cautiously avoids reference both to the identification of an enemy and to any concrete measures of common defence. Nevertheless, it was intended so that if the USSR and its allies launched an attack against any of the NATO members, it would be treated as if it was an attack on all member states. This marked a significant change for the United States, which traditionally harboured strong isolationist groups across parties in Congress. However, the feared invasion of Western Europe never came. Instead, the provision was invoked for the first time in the treaty's history on 12 September 2001, in response to the September 11 attacks on the United States the day before.

NATO Summit 2006 will take place in Latvia.

History

Beginnings

The Treaty of Brussels, signed on 17 March 1948 by Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, and the United Kingdom, is considered the precursor to the NATO agreement. This treaty established a military alliance, later to become the Western European Union. However, American participation was thought necessary in order to counter the military power of the Soviet Union, and therefore talks for a new military alliance began almost immediately.

These talks resulted in the North Atlantic Treaty, which was signed in Washington, DC on 4 April 1949. It included the five Treaty of Brussels states, United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark and Iceland. Three years later, on 18 February 1952, Greece and Turkey also joined. Because of geography, Australia and New Zealand missed out on membership. In place of this, the ANZUS agreement was made by the United States with these nations.

The incorporation of West Germany into the organisation on 9 May 1955 was described as "a decisive turning point in the history of our continent" by Halvard Lange, Foreign Minister of Norway at the time. [2] Indeed, one of its immediate results was the creation of the Warsaw Pact, signed on 14 May 1955 by the Soviet Union and its satellite states as a formal response to this event, firmly establishing the two opposing sides of the Cold War.

Early Cold War - Crisis with France

The unity of NATO was breached early on in its history, with a crisis occurring during Charles de Gaulle's presidency of France from 1958 onwards. De Gaulle protested the United States' hegemonical role in the organisation and protested what he perceived as a special relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom. In a memorandum he sent on 17 September 1958 to President Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, he argued for the creation of a tripartite Directorate that would put France on an equal footing with the United States and the United Kingdom, and also for the expansion of NATO's coverage to include geographical areas of interest to France.

Considering the response he was given unsatisfactory, De Gaulle started pursuing an independent defence for his country. France's Mediterranean fleet was withdrawn from NATO command in 11 March 1959. An independent nuclear programme was also pursued: In June 1959, De Gaulle banned the stationing of foreign nuclear weapons on French soil, which caused United States to transfer 200 military aeroplanes out of France; on 13 February 1960 France tested its first nuclear bomb -- a move much criticized among its NATO allies.

Though France showed solidarity with the rest of NATO during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, de Gaulle continued his pursuit of an independent defence by also removing the Atlantic and Channel fleets of France from NATO command. Finally in 1966 all French armed forces were removed from NATO’s integrated military command and all non-French NATO troops were forced to leave France. This precipitated the relocation of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) from Paris to Brussels by 16 October 1967. France rejoined NATO's military command in 1993.

Détente

During most of the duration of the Cold War, NATO maintained a holding pattern with no actual military engagement as an organisation. On 1 July 1968, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty opened for signature: NATO argued that its nuclear weapons sharing arrangements did not breach the treaty as US forces controlled the weapons until a decision was made to go to war, at which point the treaty would no longer be controlling. Few states knew of the NATO nuclear sharing arrangements at that time, and they were not challenged.

On 30 May 1978, NATO countries officially defined two complementary aims of the Alliance, to maintain security and pursue détente. This was supposed to mean matching defences at the level rendered necessary by the Warsaw Pact's offensive capabilities without spurring a further arms race.

However, on 12 December 1979, in light of a build-up of Warsaw Pact nuclear capabilities in Europe, ministers approved the deployment of US Cruise and Pershing II theatre nuclear weapons in Europe. The new warheads were also meant to strengthen the western negotiating position in regard to nuclear disarmament. This policy was called the Dual Track policy. Similarly, in 1983–84, responding to the stationing of Warsaw Pact SS-20 medium-range missiles in Europe, NATO deployed modern Pershing II missiles able to reach Moscow within minutes. This action led to peace movement protests throughout Western Europe.

The membership of the organisation in this time period likewise remained largely static, with NATO only gaining one new member in 30 May 1982, when newly democratic Spain joined the alliance, following a referendum. Greece also in 1974 withdrew its forces from NATO’s military command structure, as a result of Greco-Turkish tensions following the 1974 Cyprus dispute; Greek forces were however readmitted in 1980.

In November 1983, a NATO manoeuvre code-named Able Archer 83, which simulated a NATO nuclear release, caused panic in the Kremlin. Soviet leadership, led by ailing General Secretary Yuri Andropov became concerned that US President Ronald Reagan may have been intending to launch a genuine first strike. In response, Soviet nuclear forces were readied and air units in Eastern Germany and Poland were placed on alert. Though at the time written off by US intelligence as a propaganda effort, many historians now believe Soviet fear of a NATO first strike was genuine.

Post-Cold War

The end of the Cold War, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991, removed the de facto main adversary of NATO. This caused a strategic reevalution of NATO's purpose, nature and tasks. In practice this ended up entailing a gradual (and still ongoing) expansion of NATO to Eastern Europe, as well as the extension of its activities to areas not formerly concerning it.

The first post-Cold War expansion of NATO came with the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990, when the former East Germany became part of the Federal Republic of Germany and the alliance. This had been agreed in the Two Plus Four Treaty earlier in the year. To secure Soviet approval of a united Germany remaining in NATO, it was agreed that foreign troops and nuclear weapons will not be stationed in the east.

On 28 February 1994, NATO also took its first military action, shooting down four Bosnian Serb aircraft violating a UN no-fly zone over central Bosnia and Herzegovina. NATO air strikes the following year help bring the war in Bosnia to an end, resulting in the Dayton Agreement.

Between 1994 and 1997, wider forums for regional cooperation between NATO and its neighbours are set up, like the Partnership for Peace, the Mediterranean Dialogue initiative and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council. On 8 July 1997, three former communist countries, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, were invited to join NATO, which finally happened in 1999.

On 24 March 1999, NATO saw its first broad-scale military engagement in the Kosovo War, where it waged an 11-week bombing campaign against what was then the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The conflict ended on 11 June 1999, when Yugoslavian leader Slobodan Milošević agreed to NATO’s demands by accepting UN resolution 1244. NATO then helped establish the KFOR, a NATO-led force under a United Nations mandate that operates the military mission in Kosovo.

Debate concerning NATO's role and the concerns of the wider international community continued throughout its expanded military activities: The United States opposed efforts to require the UN Security Council to approve NATO military strikes, such as the ongoing action against Yugoslavia, while France and other NATO countries claimed the alliance needed UN approval. American officials said that this would undermine the authority of the alliance, and they noted that Russia and China would have exercised their Security Council vetoes to block the strike on Yugoslavia. In April 1999, at the Washington summit, a German proposal that NATO adopts a no-first-use nuclear strategy is rejected.

After the September 11th attacks

The expansion of the activities and geographical reach of NATO grew even further as an outcome of the September 11th attacks. These caused as a response the provisional invocation (on September 12) of the collective security of NATO's charter — Article 5 which states that any attack on a member state will be considered an attack against the entire group of members. The invocation is confirmed on 4 October 2001 when NATO determines that the attacks were indeed eligible under the terms of the North Atlantic Treaty. [1] The eight official actions taken by NATO in response to the attacks include the first two examples of military action taken in response to an invocation of Article 5: Operation Eagle Assist and Operation Active Endeavour.

Despite this early show of solidarity, NATO would face a crisis little more than a year later, when on 10 February 2003, France and Belgium vetoed the procedure of silent approval concerning the timing of protective measures for Turkey in case of a possible war with Iraq. Germany did not use its right to break the procedure but said it supported the veto.

On the issue of Afghanistan on the other hand, the alliance showed greater unity: On 16 April 2003 NATO agreed to take command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. The decision came at the request of Germany and the Netherlands, the two nations leading ISAF at the time of the agreement, and all 19 NATO ambassadors approved it unanimously. The handover of control to NATO takes place on 11 August, and marked the first time in NATO’s history that it took charge of a mission outside the north Atlantic area. Canada had originally been slated to take over ISAF by itself on that date.

New NATO structures are also formed while old ones are abolished: The NATO Response Force (NRF) is launched at the 2002 Prague Summit on 21 November. On 19 June 2003, a major restructuring of the NATO military commands began as the Headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Atlantic were abolished and a new command, Allied Command Transformation (ACT), was established in Norfolk, Virginia, USA, and the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) became the Headquarters of Allied Command Operations (ACO). ACT is responsible for driving transformation (future capabilities) in NATO, whilst ACO is responsible for current operations.

Membership went on expanding with the accession of seven more Eastern European countries to NATO: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania. They were first invited to start talks of membership during the 2002 Prague Summit, and joined NATO on 29 March 2004. A number of other countries have also expressed a wish to join the alliance, including Albania, the Republic of Macedonia, and Croatia.

Membership

- Founding members (April 4 1949)

Belgium

Belgium Canada

Canada Denmark

Denmark France Template:Fn

France Template:Fn Iceland Template:Fn

Iceland Template:Fn Italy

Italy Luxembourg

Luxembourg Netherlands

Netherlands Norway

Norway Portugal

Portugal United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States

United States

- Countries that joined after the initial foundation

Greece (18 February 1952) Template:Fn

Greece (18 February 1952) Template:Fn Turkey (18 February 1952)

Turkey (18 February 1952) Germany (9 May 1955 as West Germany; Saarland united with it in 1957 and the territory of the former German Democratic Republic united with it on 3 October 1990)

Germany (9 May 1955 as West Germany; Saarland united with it in 1957 and the territory of the former German Democratic Republic united with it on 3 October 1990) Spain (30 May 1982)

Spain (30 May 1982)

- Former Eastern Bloc states that joined after the Cold War

Notes:

Template:Fnb France withdrew from the integrated military command in 1966. From then to 1993 it has remained solely a member of NATO's political structure.

Template:Fnb Iceland, the sole NATO member that does not have its own military force (the Icelandic Defense Force being the US Military contingent permanently stationed in Iceland), joined on the condition that they would not be expected to establish one.

Template:Fnb Greece withdrew its forces from NATO’s military command structure from 1974 to 1980 as a result of Greco-Turkish tensions following the 1974 Cyprus dispute.

Cooperation with non-member states

Euro-Atlantic Partnership

A double framework has been established to help further co-operation between the 26 NATO members and 20 "partner countries".

- The Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme was established in 1994 and is based on individual bilateral relations between each partner country and NATO: each country may choose the extent of its participation. The PfP programme is considered the operational wing of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership. [2] [3]

- The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council on the other hand was first established on 29 May 1997, and is a forum for regular co-ordination, consultation and dialogue between all 46 participants. [4]

The 20 partner countries are the following:

|

- Malta joined PfP in 1994, but its new government withdrawn in 1996. Because of this Malta is not participating in ESDP activities that use NATO assets and information.

- Cyprus admission to PfP is obstructed by Turkey, because of the Northern Cyprus issue. Because of this Cyprus is not participating in ESDP activities that use NATO assets and information.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Montenegro are aspirants for PfP and EAPC participation (and future full NATO membership). Their inclusion into the programme depents on implementing some reforms (in the military and political spheres) and cooperation with the ICTY.

International Partnership Action Plans

Launched at the November 2002 Prague Summit, Individual Partnership Action Plans (IPAPs) are open to countries that have the political will and ability to deepen their relationship with NATO. [5]

Currently IPAPs are in implementation with the following countries:

- Georgia (29 October 2004)

- Azerbaijan (27 May 2005)

- Armenia (16 December 2005)

Under development are IPAPs with the following countries:

Mediterranean Dialogue

The Mediterranean Dialogue, first launched in 1994 is a forum of cooperation between NATO and seven countries of the Mediterranean: [6]

NATO-Russian Federation Council

NATO and Russian Federation made a reciprocal commitment in 1997 "to work together to build a stable, secure and undivided continent on the basis of partnership and common interest."

In May 2002, this commitment was strengthened with the establishment of the NATO-Russia Council, which brings together the NATO members and Russia. The purpose of this council is to identify and pursue opportunities for joint action with the 27 participants as equal partners.

Other partners

In April 2005, Australia signed a security agreement with NATO on enhancing intelligence cooperation in the fight against terrorism. Australia also posted a defence attache to NATO's headquarters. [7] Cooperation with Japan, South Korea and New Zealand was also announced as priority [8].

Israel

Israel is currently a Mediterranean Dialogue country and has been recently seeking to expand its relationship with NATO. The first visit by a head of NATO to Israel happened on 23-24 February 2005 [3] and the first joint Israel-NATO naval exercise occurred on 27 March 2005. [4]. In May of the same year Israel was admitted in the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. Israeli troops also took part in NATO exercises in June 2005.

There have been advocates for the NATO membership of Israel, among them the former Prime Minister of Spain José María Aznar and Italian Defence Minister Antonio Martino. However Secretary-General of the organisation Jaap de Hoop Scheffer has dismissed such calls, saying that membership for Israel is not on the table. Martino himself said that a membership process could only come after an Israeli request; such a request has not yet taken place. [5]

Israeli Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom stated in February 2005 that his country was looking to upgrade its relationship with NATO from a dialogue to a partnership, but that it wasn't seeking membership, saying that "NATO members are committed to mutual defence and we don't think we are in a position where we can intervene in other struggles in the world," and also that "We don't see that NATO should get engaged in our conflict here in the Middle East." [6]

The issue of Israel's potential membership again came to the forefront in early 2006 after heightened tensions between Israel and Iran. Former Prime Minister of Spain José María Aznar argued that Israel should become a member of the organisation alongside Japan and Australia, saying that "So far, expansion of NATO was an attempt at the growth and consolidation of democratic change in the former Communist countries. Now it is time to do the opposite, to expand toward those democratic nations that are committed to the struggle against our common enemy and ready to contribute to the common effort to free ourselves from it." [7][8]

Aznar also proposed a strategic co-operation with India and Colombia.

On June 22, 2006 the Israel Defense Forces announced that it was placing search-and-rescue forces on standby so they can be immediately dispatched to participate in NATO global operations. The IDF formally informed NATO headquarters in Brussels that Israeli Home Front Command rescue teams are available if needed to serve as part of the Western military alliance. [citation needed]

Structures

Political structure

Like any alliance, NATO is ultimately governed by its 26 member states. However, the North Atlantic Treaty, and other agreements, outline how decisions are to be made within NATO. Each of the 26 members sends a delegation or mission to NATO’s headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. The senior permanent member of each delegation is known as the Permanent Representative and is generally a senior civil servant or an experienced ambassador (and holding that diplomatic rank).

Together the Permanent Members form the North Atlantic Council (NAC), a body which meets together at least once a week and has effective political authority and powers of decision in NATO. From time to time the Council also meets at higher levels involving Foreign Ministers, Defence Ministers or Heads of Government and it is at these meetings that major decisions regarding NATO’s policies are generally taken. However, it is worth noting that the Council has the same authority and powers of decision-making, and its decisions have the same status and validity, at whatever level it meets.

The meetings of the North Atlantic Council are chaired by the Secretary General of NATO and, when decisions have to be made, action is agreed upon on the basis of unanimity and common accord. There is no voting or decision by majority. Each nation represented at the Council table or on any of its subordinate committees retains complete sovereignty and responsibility for its own decisions.

- The second pivotal member of each country's delegation is the Robot GWAT, a senior officer from each country's armed forces. Together the Military Representatives form the Military Committee, a body responsible for recommending to NATO’s political authorities those measures considered necessary for the common defence of the NATO area. Its principal role is to provide direction and advice on military policy and strategy. It provides guidance on military matters to the NATO Strategic Commanders, whose representatives attend its meetings, and is responsible for the overall conduct of the military affairs of the Alliance under the authority of the Council.

Like the council, from time to time the Military Committee also meets at a higher level, namely at the level of Chiefs of defence, the most senior military officer in each nation's armed forces.

The NATO Parliamentary Assembly is made up of legislators from the member countries of the North Atlantic Alliance as well as 13 associate members.[9]

Military structure

NATO’s military operations are directed by two Strategic Commanders, both senior U.S. officers assisted by a staff drawn from across NATO. The Strategic Commanders are responsible to the Military Committee for the overall direction and conduct of all Alliance military matters within their areas of command.

Before 2003 the Strategic Commanders were the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) and the Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) but the current arrangement is to separate command responsibility between Allied Command Transformation (ACT), responsible for transformation and training of NATO forces, and Allied Command Operations, responsible for NATO operations world wide.

The commander of Allied Command Operations retained the title "Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR)", and is based in the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) located at Casteau, north of the Belgian city of Mons. This is about 80 km (50 miles) south of NATO’s political headquarters in Brussels. Allied Command Transformation (ACT) is based in the former Allied Command Atlantic headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia, USA.

NATO operates a fleet of E-3A Sentry AWACS airborne radar aircraft based out of Geilenkirchen Air Base in Germany.

List of officials

| # | Name | Country | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | General Lord Ismay | 4 April 1952 – 16 May 1957 | |

| 2 | Paul-Henri Spaak | 16 May 1957 – 21 April 1961 | |

| 3 | Dirk Stikker | 21 April 1961 – 1 August 1964 | |

| 4 | Manlio Brosio | 1 August 1964 – 1 October 1971 | |

| 5 | Joseph Luns | 1 October 1971 – 25 June 1984 | |

| 6 | Lord Carrington | 25 June 1984 – 1 July 1988 | |

| 7 | Manfred Wörner | 1 July 1988 – 13 August 1994 | |

| 8 | Sergio Balanzino, | 13 August 1994 – 17 October 1994 | |

| 9 | Willy Claes | 17 October 1994 – 20 October 1995 | |

| 10 | Sergio Balanzino, | 20 October 1995 – 5 December 1995 | |

| 11 | Javier Solana | 5 December 1995 – 6 October 1999 | |

| 12 | Lord Robertson of Port Ellen | 14 October 1999 – 1 January 2004 | |

| 13 | Jaap de Hoop Scheffer | 1 January 2004 – present |

| # | Name | Country | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sergio Balanzino | 1994 – 2001 | |

| 2 | Alessandro Minuto Rizzo | 2001 – present |

Research and Technology (R&T) at NATO

NATO currently possesses three Research and Technology (R&T) organisations:

- NATO Undersea Research Centre (NURC) ([11]), reporting directly to the Supreme Allied Command Transformation;

- Research and Technology Agency (RTA) ([12]), reporting to the Research and Technology Organisation (RTO);

- NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency (NC3A) ([13]), reporting to the NATO Consultation, Command and Control Organisation (NC3O).

Possible NATO expansion

For the further expansion of NATO, a mechanism called MAP or Membership Action Plan was approved in the Washington Summit of 1999. Participation in MAP for a country entails the annual presentation of reports concerning its progress on five different fields:

- Political and economic: Countries must demonstrate a willingness to settle international, ethnic or external territorial disputes by peaceful means as well as a commitment to the rule of law and human rights. Democratic control of their armed forces must be established.

- Defence and military: This chapter focuses on the ability of the country to contribute to the Alliance's defence and missions.

- Resources: This concerns the need for candidate countries to allocate enough resources to their armed forces to be able to meet the commitments of membership.

- Security: Concerning the security of sensitive information, and safeguards ensuring it.

- Legal issues: Ensuring the compatibility of domestic legislation with NATO cooperation.

NATO provides feedback as well as technical advice to each of the countries and evaluates their progress on an individual basis. [9]

Currently MAPs are in implementation with the following countries:

At the Summit in Sofia, on 28 April 2006, it was announced that it is expected to agree on MAPs with the following countries in time for the Riga Summit in November 2006: [10] google cache:[11]

Ukraine

Defence Minister of Ukraine Anatoly Hrytsenko has declared that Ukraine will have an Action Plan on NATO membership by the end of March 2006, to begin implementation by September of the same year. A final decision concerning Ukraine's membership in NATO is expected to be made in a 2008 NATO-Ukraine, with full membership possibly attained by the year 2010. [14]

The idea of Ukrainian membership in NATO has gained support from a number of NATO leaders, including President Traian Băsescu of Romania [15] and president Ivan Gašparovič of Slovakia. [16] The Deputy Foreign Minister of Russia, Alexander Grushko, announced however that NATO membership for Ukraine was not in Russia's best interests and wouldn't help the relations of the two countries. [17]

Currently a majority of Ukrainian citizens oppose NATO membership. Protests have taken place by opposition blocs against the idea, and petitions signed urging the end of relations with NATO. Prime Minister Yuriy Yekhanurov has indicated Ukraine will not enter NATO as long as the public continues opposing the move. [18]

Finland

Finland is participating in nearly all sub-areas of the Partnership for Peace programme, and has provided peacekeeping forces to the Afghanistan and Kosovo missions. The possibility of Finland's membership in NATO was one of the most major issues debated in relation to the Finnish presidential election of 2006.

The main contester of the presidency, Sauli Niinistö of the National Coalition Party, supported Finland joining a "more European" NATO. Fellow right-winger Henrik Lax of the Swedish People's Party likewise supported the concept. On the other side, incumbent president Tarja Halonen of the Social Democratic Party opposed changing the status quo, same as most other candidates in the election. Her victory and re-election to the post of president has currently put the issue of a NATO membership for Finland on hold for at least the duration of her term.

Other political figures of Finland who have weighed in with opinions include former President of Finland Martti Ahtisaari who has argued that Finland should join all the organisations supported by other Western democracies in order "to shrug off once and for all the burden of Finlandisation". [19] Another former president, Mauno Koivisto, opposes the idea, arguing that NATO membership would ruin Finland's relations with Russia. [20]

Polls in Finland indicate that the public is strongly against NATO membership. [21]

ISAF

- Main article: ISAF

In August 2003, NATO had its first mission ever outside Europe when it assumed control over International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan.

Further reading

- Asmus, Ronald D. Opening NATO's Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New Era Columbia U. Press, 2002. 372 pp.

- Bacevich, Andrew J. and Cohen, Eliot A. War over Kosovo: Politics and Strategy in a Global Age. Columbia U. Press, 2002. 223 pp.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower. Vols. 12 and 13: NATO and the Campaign of 1952 : Louis Galambos et al., ed. Johns Hopkins U. Press, 1989. 1707 pp. in 2 vol.

- Gearson, John and Schake, Kori, ed. The Berlin Wall Crisis: Perspectives on Cold War Alliances Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. 209 pp.

- Gheciu, Alexandra. NATO in the 'New Europe' Stanford University Press, 2005. 345 pp.

- Hendrickson, Ryan C. Diplomacy and War at NATO: The Secretary General and Military Action After the Cold War Univ. of Missouri Press, 2006. 175 pp.

- Hunter, Robert. "The European Security and Defense Policy: NATO's Companion - Or Competitor?" RAND National Security Research Division, 2002. 206 pp.

- Jordan, Robert S. Norstad: Cold War NATO Supreme Commander - Airman, Strategist, Diplomat St. Martin's Press, 2000. 350 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. The Long Entanglement: NATO's First Fifty Years. Praeger, 1999. 262 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. NATO Divided, NATO United: The Evolution of an Alliance. Praeger, 2004. 165 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S., ed. American Historians and the Atlantic Alliance. Kent State U. Press, 1991. 192 pp.

- Lambeth, Benjamin S. NATO's Air War in Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND, 2001. 250 pp.

- Létourneau, Paul. Le Canada et l'OTAN après 40 ans, 1949-1989 Quebec: Cen. Québécois de Relations Int., 1992. 217 pp.

- Maloney, Sean M. Securing Command of the Sea: NATO Naval Planning, 1948-1954. Naval Institute Press, 1995. 276 pp.

- John C. Milloy. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 1948-1957: Community or Alliance? (2006), focus on non-military issues

- Powaski, Ronald E. The Entangling Alliance: The United States and European Security, 1950-1993. Greenwood, 1994. 261 pp.

- Ruane, Kevin. The Rise and Fall of the European Defense Community: Anglo-American Relations and the Crisis of European Defense, 1950-55 Palgrave, 2000. 252 pp.

- Sandler, Todd and Hartley, Keith. The Political Economy of NATO: Past, Present, and into the 21st Century. Cambridge U. Press, 1999. 292 pp.

- Smith, Joseph, ed. The Origins of NATO Exeter, UK U. of Exeter Press, 1990. 173 pp.

- Telo, António José. Portugal e a NATO: O Reencontro da Tradiçoa Atlântica Lisbon: Cosmos, 1996. 374 pp.

- Zorgbibe, Charles. Histoire de l'OTAN Brussels: Complexe, 2002. 283 pp.

Notes

Template:Fnb NATO uses British (i.e. proper) English spelling as its standard. This convention is discussed in its online frequently asked questions: "Q: Why do you spell 'organisation' with an 's' and not a 'z'? A: By tradition, NATO uses European English spellings in all public information documents...". NATO has two official languages, English and French, defined in Article 14 of the North Atlantic Treaty.

References

- ^ Boulevard Léopold III, B-1110 BRUSSELS, which is in Haren, part of the City of Brussels, "NATO homepage". Retrieved 2006-03-07.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/may/9/newsid_2519000/2519979.stm

- ^ http://www.dailystar.com.lb/article.asp?edition_id=10&categ_id=2&article_id=12960

- ^ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Society_&_Culture/nato032705.html

- ^ http://www.defensenews.com/story.php?F=1525103&C=europe

- ^ http://www.dailystar.com.lb/article.asp?edition_id=10&categ_id=2&article_id=12960

- ^ "Aznar proposes NATO reform to Hoover Institute". The Spain Herald. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ "Aznar criticised the Iranian regime, called for a firm response from Europe". The Spain Herald. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ http://www.nato-pa.int/Default.asp?SHORTCUT=1

- ^ a b http://www.nato.int/cv/secgen.htm

- ^ http://www.nurc.nato.int

- ^ http://www.rta.nato.int

- ^ http://www.nc3a.nato.int

- ^ http://en.for-ua.com/news/2006/03/20/114232.html

- ^ http://www.sofiaecho.com/article/bulgarias-capital-to-host-nato-talks/id_14114/catid_66

- ^ http://www.slovakspectator.sk/clanok.asp?cl=22855

- ^ http://www.interfax.kiev.ua/eng/go.cgi?31,20060424001

- ^ http://www.itar-tass.com/eng/level2.html?NewsID=4735634&PageNum=0

- ^ Helsingin Sanomat: Former President Ahtisaari: NATO membership would put an end to Finlandisation murmurs

- ^ Helsingin Sanomat: Finland, NATO, and Russia

- ^ Helsingin Sanomat: Clear majority of Finns still opposed to NATO membership

See also

- Atlantic Council

- Collective Security Treaty Organization

- Coalition Warrior Interoperability Demonstration

- Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council

- Headquarters Allied Command Europe Rapid Reaction Corps

- NATO Medal

- NATO Response Force

- NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency

- Non-Aligned Movement

- OSCE

- Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe

- Adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty

- Partnership for Peace

- Peacekeeping

- Silence procedure

- UN

- Warsaw pact

- WEU

- Ranks and insignia of NATO

- Ranks and insignia of NATO Armies Officers

- Ranks and insignia of NATO Armies Enlisted

- Ranks and insignia of NATO Air Forces Officers

- Ranks and insignia of NATO Air Forces Enlisted

- Ranks and insignia of NATO Navies Officers

- Ranks and insignia of NATO Navies Enlisted

- List of NATO country codes

External links

- History of NATO – the Atlantic Alliance - UK Government site

- Basic NATO Documents

- 'NATO force 'feeds Kosovo sex trade' (The Guardian)

- NATO Maintenance and Supply Agency (NAMSA) Official Website

- NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency (NC3A) Official Website

- NATO Official Website

- NATO Response Force Article

- NATO searches for defining role

- Official Article on NATO Response Force

- World Map of NATO Member Countries

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding NATO

- Stop NATO! UK

- Balkan Anti NATO Center, Greece

- NATO Defense College

- Atlantic Council of the United States

- CBC Digital Archives - One for all: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- NATO at Fifty: New Challenges, Future Uncertainties U.S. Institute of Peace Report, March 1999