Cueva de las Manos

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Hands, at the Cave of the Hands | |

| Official name | Cueva de las Manos, Río Pinturas |

| Location | Santa Cruz, Argentina |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Reference | 936 |

| Inscription | 1999 (23rd Session) |

| Area | 600 ha (1,500 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 2,331 ha (5,760 acres) |

| Coordinates | 47°09′21″S 70°39′26″W / 47.155774°S 70.657256°W |

Cueva de las Manos (Spanish for Cave of the Hands or Cave of Hands) is a cave and complex of rock art sites in the province of Santa Cruz, Argentina, 163 km (101 mi) south of the town of Perito Moreno. It is named for the hundreds of paintings of hands stenciled, in multiple collages, on the rock walls. The art in the cave dates to between 11,000 to 7,000 BC, during the Archaic period of Pre-Columbian South America, or the late Pleistocene to early Holocene geological periods. Several waves of people occupied the cave over time, as evidenced by some of the early artwork that has been radiocarbon dated to about 7300 BC. The age of the paintings was calculated from the remains of bone-made pipes used for spraying the paint on the wall of the cave to create the artwork. The site is considered by some scholars to be the best material evidence of South American early hunter-gatherer groups.

The site was last inhabited around 700 AD, possibly by ancestors of the Tehuelche people. Argentine surveyor and archaeologist Carlos J. Gradin and his team conducted the most important research on the site in 1964, when they began excavating sites during a 30-year study of cave art in and around Cueva de las Manos. The importance of Gradin's discoveries to the country's natural and cultural heritage resulted in the site being named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. The site is a National Historic Monument and a National Historic Site in Argentina.

Location

The cave lies in the valley of the Pinturas River, in an isolated location in the Patagonian landscape.[1] The area itself is on the upper part of the Deseado Basin, at the base of a stepped cliff[2][3] in the Pinturas Canyon.[4] It lies around 165 kilometers (103 mi) south of Perito Moreno, a town in northwest Santa Cruz Province, Argentina.[5][6] The site is part of Perito Moreno National Park,[7] as well as the Cueva de las Manos Provincial Park.[8]

Climate

The climate of the cave area can best be described as precordilleran steppe (or "grassy foothills").[9][10] The climate is cold and dry,[11] with very low humidity;[12] the area receives a total annual precipitation of less than 20 millimeters (0.79 in) per year.[13] The topography of the canyon prevents the strong westward winds that are natural to the region, making winters in the area less severe.[14]

Access

There are three main access points to the cave: Estancia Cueva de las Manos, from Bajo Caracoles, and a midway access road between the two points.[15] The cave is most easily reached by a gravel road, which leaves Ruta 40 (Route 40)[6] north of Bajo Caracoles and runs 43 km (27 mi) northeast to the south side of the Pinturas Canyon.[15] The north side of the canyon can be reached by rough, but shorter, roads from Ruta 40.[16] A 3 km (1.9 mi) path connects the two sides of the canyon, but there is no road link.[17][15]

History

When the site was occupied, the Pinturas and Deseado Rivers drained into the Atlantic Ocean, and provided water for herds of guanacos, making the area attractive to Paleoindians.[18] However, as the glacial ice fields melted, the Baker River captured the drainage of the eastward flowing rivers and redirected the flow to the Pacific Ocean.[18] This led to a progressive abandonment of the Las Manos site.[18]

Projectile points, a bola stone fragment, and side-scrapers have been found alongside guanaco, puma, fox, bird and other small animals' remains at the site.[3][19] The natives used bolas and ambush tactics to hunt guanacos, their primary food source.[a][20][21] The Pre-Columbian economy of Patagonia as a whole depended on hunting-gathering. Francisco Mena states in "...[in the] Middle to Late Holocene Adaptations in Patagonia ... neither agriculture nor fully fledged pastoralism ever emerged."[22] Carlos Gradin remarked in his writings that all the rock art in the area shows the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the artists who made it.[23]

Various groups inhabited the Las Manos site, including the long-since vanished Toldense people who lived in the caves until the third or second millennium BC.[24] The site was last inhabited around 700 AD, with the final cave dwellers possibly being ancestors of the Tehuelche tribes.[25][26][27] The existence of obsidian in the area—which is not natural to the region—implies a broad-ranging network of trade between peoples of the cave area and distant tribal groups.[28]

Modern study and protection

Father Alberto Maria de Agostini first wrote about the site in 1941.[29][30] Argentine surveyor and archaeologist Carlos Gradin and his team began the most profound research on the site in 1964, when they initiated a 30-year-long study of the caves and their art.[31][20] Gradin's work has helped to separate the different stylistic sequences of the cave.[4]

Cueva de las Manos is a National Historic Monument in Argentina,[32] and has been listed as a National Historic Site since 1993.[33] It has also been listed as a World Heritage Site since 1999.[12] In 2018, the site received its own provincial park.[8]

Cave

The main cave is about 66 feet (20 meters) deep, and is composed of the cave itself, two outcroppings, and the walls at either side of the entrance.[34] The entrance faces approximately northeast and is about 50 feet (15 meters) in height by 50 feet (15 meters) wide.[34] The paintings on the cave's wall span about 200 by 650 feet (61 m × 198 m).[34] The initial height of the cave is 33 ft (10 m).[35] The ground inside has an upward slope; as a result, the height is eventually reduced to no more than 2 m (6.6 ft).[35]

Artwork

Cueva de las Manos is named for the hundreds of hand paintings stenciled into multiple collages on the rock walls.[36] The art in the Cueva de las Manos is some of the most important art in the New World, and by far the most famous among rock art in the Patagonian region.[20][26][37][38] The art dates to between 11,000 to 7,000 BC,[39] during the Archaic period of Pre-Columbian South America,[40][41] or the late Pleistocene to early Holocene geological periods.[26][42] The oldest-known cave paintings in South America are contained within the cave.[43]

The artwork not only decorates the interior of the cave but also the surrounding cliff faces and exterior.[44] The cave's art can be divided by subject into three basic categories: people, the animals they ate, and the human hand.[20] Inhabitants of the Las Manos site hunted guanacos for survival; a dependency that is reflected in their artwork as totemic-like depictions of the creatures.[20]

The artwork's authenticity has been verified.[4] Several waves of people occupied the cave over time as evidenced by some of the early artwork that has been radiocarbon dated to about 7300 BC.[25] The age of the paintings was calculated from the remains of bone-made pipes used for spraying the paint on the wall of the cave to create the stenciled artwork of the hand collages.[45] According to Fanning et al., it is "...the best material evidence of early hunter gatherer groups in South America."[27]

Forms

The works in the cave can be described as naturalistic.[39] Over time, they gradually became more stylized.[20][4]

There are over 2,000 handprints in and around the cave.[35] Most of the images are painted as negatives or stencilled, alongside some positive handprints.[46] A survey in the 1970s counted 829 left hands to 31 right.[30][47] This suggests that painters held a spray pipe (possibly made from a bird bone) with their right hand.[46][48][49] Some hands are missing fingers, which could be due to necrosis, amputation, or deformity, but might also indicate the use of sign language or bending fingers to convey meaning.[50][51]

The varying depth of the rock face alters the "canvas" of the artwork, and the different depths from the viewer alters the way the images are seen, based on where the viewer is standing. There is a large amount of superimpositioning (overlap) of the hands in different areas as well,[20][4] with some areas of the art containing so much that the hands form a palimpsest background of layered color.[52][53] Along with the superimpositioned masses of images, there are many purposefully placed single hands.[53]

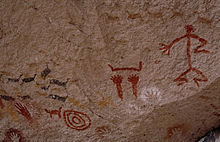

There are also depictions of human beings, guanacos,[25] rheas, felines and other animals, as well as geometric shapes, zigzag patterns, representations of the sun, and hunting scenes.[35][49] The hunting scenes are naturalistic portrayals of a variety of hunting techniques, including the use of bolas.[a][25][21] Similar paintings, though in smaller numbers, can be found in nearby caves. There are also red dots on the ceilings, probably made by submerging their hunting bolas in ink, and then throwing them up.[4][49]

The same wildlife depicted in the artwork exists in the area today.[44][7] Most prominent among the animals are the guanacos, upon which the natives depended for survival.[20] There are repeated scenes of guanacos being surrounded as they are hunted,[35] suggesting that this was the preferred tactic for killing the creatures.[20]

Cultural context

Little is known about the culture of those who made these works aside from the tools they used and what they hunted. Modern research is left to speculate about their culture and what life was like in the societies that created it.[20] The art shows the people of this area were not merely restricted to stone tools and subsistence, but had a symbolic element to their culture.[42]

Purpose

The exact function or purpose of this art is unknown, although some findings have suggested it may have had a religious or ceremonial purpose[20][54] as well as a decorative one.[50] Scholars have suggested that hands are indicative of the human desire to be remembered,[48] or to record that they were there.[49][55] That so many people contributed to the artwork for thousands of years suggests the cave held great significance for the artists who painted on its walls.[4] The fact that a large number of people gathered in one place to contribute to the rock art for such a long period, shows a large cultural significance, or at least usefulness,[b] to those who participated.[4]

Materials

The binder used in the artwork is unknown but the mineral pigments include iron oxides, producing reds and purples; kaolin, producing white; natrojarosite, producing yellow; manganese oxide (pyrolusite),[13] which makes black; and copper oxide,[c] making green.[59][25][7] Haematite, goethite, and green earth have also been detected.[13] Moreover, Wainwright et al. state that "gypsum, quartz, and calcium oxalate have been admixed with the pigments".[13]

Stylistic Groups

Significant research and archaeology on the rock art of the cave has led specialists to categorize the art into four stylistic groups, proposed by Carlos Gradin and adapted and modified by others:[60] A, B, B1, and C,[61] also known as Río Pinturas I, II, III, and IV, respectively.[4] These stylistic groups, separated into three phases of production, cover a time period of around eight millennia.[26] The first two groups were partly conceived to differentiate group A's dynamic depiction of guanacos from group B's static depiction of them.[61]

Stylistic Group A

Stylistic Group A (also known as Río Pinturas I) is the art of the first hunter-gatherers who lived in the area,[4] and is the oldest style in the cave, which can be traced as far back to around 7,300 BC.[27][26][20] The style is naturalistic and dynamic, and encompasses polychrome, dynamic hunting scenes along with negative human hand motifs.[26][4] The imagery takes advantage of the grooves in the rock face itself to form part of the art.[4] The hunters depicted in the scenes were likely long distance hunters, and the hunting scenes often depicted ambush or surround tactics being used when hunting guanacos.[4]

It is likely that the eruption of the Hudson volcano around 4770/4675 BC caused the end of this stylistic group.[62]

Stylistic Groups B and B1

A new cultural group, entering the scene before 5,000 BC, until around 1,300 BC, created the art of what is now considered stylistic groups B (Río Pinturas II) and B1 (Río Pinturas III).[4]

Around 5,000 BC, Group B was born.[26] Static, isolated groups of guanacos with large bellies, possibly pregnant, replace the lively hunting scenes that marked the previous group.[26][4][63] Large groups of superimposed handprints, numbering around 2,000, in many colors, are associated with Group B,[4] as are some more rare motifs of human and animal footprints.[20]

In Group B1, composing what could be considered the latter part of Group B, the forms become more and more schematic, and figures, human and animal, become more stylized;[64] the group includes hand stencils, bola marks, and dotted line patterns.[4][26]

Stylistic Group C

Stylistic Group C, Río Pinturas IV, begins around 700 AD and marks the last of the stylistic sequences in the cave.[4][26] The group focuses around abstract geometric figures[26] including highly schematic silhouettes of both animal and human figures, alongside circles, zigzag patterns, dots, and more hands superimposed onto larger groups of hands.[4][26] The primary color is red.[4][26]

-

Hunting scene

-

Rhea feet[4] among human hands

Cultural impact

Every February the nearby town of Moreno hosts a celebration in honor of the caves[4][65] called Festival Folkólorico Cueva de las Manos.[66] Significant numbers of tourists visit the cave,[23] which is known worldwide.[3][2][67] The site's addition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site has contributed to this effect, acting as a type of "quality seal" for potential tourists and the global cultural tourism industry.[68] The cave and its paintings have served as the inspiration and setting for the popular children's book Ghost Hands, written by T. A. Barron and illustrated by William Low.[69]

Threats to conservation

The park faces new setbacks to its preservation in recent times, particularly from tourism. The number of tourists visiting the site has increased by a factor of four since its inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1999.[70] This large influx of tourists has brought new challenges for those seeking to preserve the site.[4] Currently, the most significant threat is graffiti.[13][32] Other forms of vandalism, such as visitors taking pieces of painted rock from the walls and touching the paintings with their hands, have also left damage and contributed to the overall negative impact of tourism.[12]

In response to these issues, the site is closed off with chain-link fencing[32][71] with a boardwalk to secure the site from the demands of increased ecotourism.[72][70] The boardwalk helps to control the movements of visitors and serves as a convenient walkway.[70] The site has also been equipped with sanctioned walking trails, a guide lodge, railings and a parking lot.[23] A team of professionals from Argentina's National Anthropological Institute (INAPL) and the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) supervised the construction of these facilities.[23] An awareness program has also been undertaken to educate tourists and visitors to the site, including local guides,[72][73] and to facilitate greater involvement by local communities.[23] To access the site, visitors must be accompanied by a tour guide.[74][71]

Despite these measures taken to protect the site, the local provincial government,[72] the Argentinian government, and the UNESCO have been criticized for not doing enough to protect it.[75] The provincial government in particular has been criticized for falling short of the recommendations of the INAPL, including the need for additional staffing and a permanent on-site archaeologist.[72]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Bolas were weapons designed with cords, having weights on each end that were thrown at the legs of animals to trap them allowing them to be killed by hunters.

- ^ One theory posits that perhaps the art served as boundary markers between peoples, showing territoriality as well as ensuring the cooperation of others by functioning as aggregation sites.[56] There is also speculation that the works were part of hunting magic,[57][58] although this is largely unproven.

- ^ This pigment is used more rarely, having been drawn from a source 150 kilometers (93 mi) away.[59]

References

- ^ Finlay, Victoria (2014). The brilliant history of color in art. J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-60606-429-0. OCLC 879583340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Mena, McEwan & Borrero (1997), p. 38

- ^ a b c Borrero, Luis Alberto (1 September 1999). "The Prehistoric Exploration and Colonization of Fuego-Patagonia". Journal of World Prehistory. 13 (3): 321–355. doi:10.1023/A:1022341730119. S2CID 161836687.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Onetto, María; Podestá, María Mercedes (2011). "Cueva de las Manos: An Outstanding Example of a Rock Art Site in South America" (PDF). Adoranten. Scandinavian Society for Prehistoric Art: 67–78.

- ^ Moss, Chris (2014-12-13). "Guide to Patagonia: What to Do, How to Do It, and Where to Stay". The Guardian. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ^ a b Tang, Jin Bo (April 2015). "The Hand in Art: 'Hands' in the Artwork of Patagonia". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 40 (4): 806–808. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.01.022. S2CID 71792792. PII S0363-5023(15)00081-7.

- ^ a b c Lundborg, Göran (2014). "Handprints from the Past". The Hand and the Brain. pp. 41–48. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-5334-4_5. ISBN 978-1-4471-5333-7.

- ^ a b "Se concretó la donación de tierras para el Parque Provincial Cueva de las Manos". Argentina.gob.ar (in Spanish). 2020-07-13. Retrieved 2021-06-19.

- ^ Orquera (1987), p. 378

- ^ Aschero (2018), p. 213

- ^ Srur, Ana M.; Villalba, Ricardo; Baldi, Germán (2011). "Variations in Anarthrophyllum rigidum radial growth, NDVI and ecosystem productivity in the Patagonian shrubby steppes". Plant Ecology. 212 (11): 1841–1854. doi:10.1007/s11258-011-9955-6. JSTOR 41508649. S2CID 1008572.

- ^ a b c UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Cueva de las Manos, Río Pinturas". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e Wainwright, Ian N.M.; Helwig, Kate; Rolandi, Diana S.; Gradin, Carlos; Mercedes Podestá, M.; Onetto, María; Aschero, Carlos A. (2002). Rock paintings conservation and pigment analysis at Cueva de las Manos and Cerro de los Indios, Santa Cruz (Patagonia), Argentina. Vol. 2. ICOM Preprints. pp. 583 & 585. OCLC 938407252.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ World Heritage Papers 13 (PDF). Linking Universal and Local Values: Managing a Sustainable Future for World Heritage. 24 May 2003. p. 159.

- ^ a b c Bernhardson (2014), pp. 383–384

- ^ Albiston, Isabel; Brown, Cathy, Clark, Gregor, Egerton, Alex; Grosberg, Michael; Kaminski, Anna; McCarthy, Carolyn, Mutić, Anja; Skolnick, Adam (2018). Argentina. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-78657-066-6. OCLC 1038423144.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Moon Travel Guide, Argentina". Archived from the original on 2012-06-17. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- ^ a b c Isla, Federico Ignacio; Espinosa, Marcela; Iantanos, Nerina (1 March 2015). "Evolution of the Eastern flank of the North Patagonian Ice Field: The deactivation of the Deseado River (Argentina) and the activation of the Baker River (Chile)". Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. 59 (1): 119–131. Bibcode:2015ZGm....59..119I. doi:10.1127/0372-8854/2014/0149. In "New Findings from Department of Geology in Geomorphology Provides New Insights [Evolution of the Eastern flank of the North Patagonian Ice Field: The Deactivation of the Deseado River (Argentina) and the Activation of the Baker River (Chile)]". Science Letter. Atlanta, GA: NewsRX LLC. 1 May 2015. p. 936. Gale A415804207.

- ^ Mena, McEwan & Borrero (1997), pp. 38–39, 48–49 & 50–51

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Schobinger (2016), pp. 39–44, 57–61, 67 & 70

- ^ a b Mena, McEwan & Borrero (1997), pp. 38–39, 46–47, 48–49 & 50–51

- ^ Mena, McEwan & Borrero (1997), pp. 46–47

- ^ a b c d e Fiore (2008), p. 315

- ^ Orquera (1987), p. 370

- ^ a b c d e "Cueva de las Manos, Río Pinturas." UNESCO World Heritage List. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Art & Place: Site-Specific Art of the Americas. Editorial Director: Amanda Renshaw; Text & Expertise provided by Daniel Arsenault et al. London: Phaidon Press. 2013. pp. 354–355. ISBN 978-0-7148-6551-5. OCLC 865298990.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Fanning, Irene; Glusberg, Jorge; Frei, Cheryl Jiménez; Perazzo, Nelly; Hartop, Christopher; Pérez, Jorge F. Rivas; Corcuera, Ruth; Reyes, Marta Arciprete de; Vaquero, Julieta Zunilda (March 9, 2020), "Argentina, Republic of", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press (published 2003), doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t003988, ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4, retrieved 2021-04-04

- ^ Magnin, L.; Lynch, V.; García Añino, E. (2 July 2020). "Intra-Site Use Patterns during the Early Holocene in the Cueva Maripe Site (Santa Cruz, Argentina)". PaleoAmerica. 6 (3): 268–282. doi:10.1080/20555563.2019.1709032. S2CID 213889275.

- ^ Gutiérrez De Angelis, Marina; Winckler, Greta; Bruno, Paula; Guarini, Carmen (2019). "Rethinking Paleolithic Visual Culture throughout immersive technology: The site 'Cueva de las Manos' as a virtual 'Denkraum' (Patagonia, Argentina)". Widok (25). doi:10.36854/widok/2019.25.2081. S2CID 229288678.

- ^ a b Podestá, María Mercedes; Raffino, Rodolfo A.; Paunero, Rafael Sebastián; Rolandi, Diana S. (2005). El arte rupestre de Argentina indígena: Patagonia (in Spanish). Grupo Abierto Communicaciones. ISBN 978-987-1121-16-8.

- ^ Delegación Buenos Aires-MINPRO. "Cueva de las Manos". Cueva de las Manos (in Spanish). Perito Moreno, Argentina. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- ^ a b c Wainwright, Ian N. M. (1995), "Conservation and recording of rock art in Argentina", CCI Newsletter, no. 16, Canadian Conservation Institute, pp. 4–5

- ^ Levrand, Norma Elizabeth; Endere, María Luz (2020). "Nuevas categorías patrimoniales. La incidencia del soft law en la reciente reforma a la ley de patrimonio histórico y artístico de Argentina" [New heritage categories: The incidence of soft law in the recent reform of the historical and artistic heritage law of Argentina]. Revista Direito GV (in Spanish). 16 (2): e1960. doi:10.1590/2317-6172201960.

- ^ a b c Schobinger (2016), p. 40

- ^ a b c d e Menon (2010), p. 243

- ^ Shally-Jensen, Michael (2015). Central & South America. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-61925-788-7. OCLC 915353454.

- ^ Menon (2010), p. 30: "Cave paintings from much earlier epochs have been discovered in several provinces, the most famous being Cueva de las Manos in Patagonia (see p243)."

- ^ Funari, Pedro Paulo A.; Zarankin, A.; Stovel, E. (2009). "South American Archaeology". In Gosden, Chris; Cunliffe, Barry; Joyce, Rosemary A. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology. pp. 958–1000. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199271016.013.0031. ISBN 978-0-19-927101-6. OCLC 277205272.

This is perhaps the best-known site in the country, because of its evocative zoomorphic, anthromorphic, and geometric rock-art panels.

- ^ a b World Heritage Sites: a Complete Guide to 1007 UNESCO World Heritage Sites (6th ed.). Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing. 2014. p. 607. ISBN 978-1-77085-640-0. OCLC 910986576.

- ^ National Geographic Society (2013-10-09). "Cuevas de las Manos". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2021-03-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Trofimova, E.; Trofimov, A. (1 September 2019). "World Subterranean Heritage". Geoheritage. 11 (3): 1113–1131. doi:10.1007/s12371-019-00351-8. S2CID 150080128.

- ^ a b Neves, Walter A.; Araujo, Astolfo G. M.; Bernardo, Danilo V.; Kipnis, Renato; Feathers, James K. (22 February 2012). "Rock Art at the Pleistocene/Holocene Boundary in Eastern South America". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e32228. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732228N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032228. PMC 3284556. PMID 22384187.

- ^ Crane, Ralph J.; Fletcher, Lisa (2015). Allen, Daniel (ed.). Cave. Earth Series. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-78023-460-1. OCLC 915154364.

- ^ a b Onetto, Maria (2014). "Cueva de las Manos, Río Pinturas Cave Art". In Smith, Claire (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Vol. 3. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 1841–1846. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1624. ISBN 978-1-4419-0426-3. LCCN 2013953915.

- ^ Wood, Barry (October 1, 2019). "Beachcombing and Coastal Settlement: The Long Migration from South Africa to Patagonia—The Greatest Journey Ever Made". Journal of Big History. 3 (4): 38. doi:10.22339/jbh.v3i4.3422.

- ^ a b Moore (2017), p. 100

- ^ References to the survey:

- Steele, James; Uomini, Natalie (2005). "Humans, tools and handedness" (PDF). In Roux, Valentine; Bril, Blandine (eds.). Stone Knapping: the Necessary Conditions for a Uniquely Hominin Behaviour. Cambridge, UK: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge. p. 234. ISBN 1-902937-34-1. OCLC 64118071.

- Moore (2017), p. 100

- ^ a b Parfit, Michael (December 2000). "Hunt for the First Americans". National Geographic. Vol. 198, no. 6. National Geographic Society. p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (September 23, 2015). A Concise History of the World. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-1-107-02837-1. OCLC 908262350.

- ^ a b Sraj, Shafic (January 2015). "The Hand in Art: The Hand Was First in Art". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 40 (1): 140. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.10.045. PII S0363-5023(14)01496-8.

- ^ Achrati, Ahmed. "Hand Prints, Footprints and the Imprints of Evolution". Rock Art Research. 25 (1): 23–33. doi:10.3316/ielapa.484264644023649 (inactive 2021-10-09). OCLC 663872753.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - ^ Dobrez, Patricia (11 December 2014). "Hand Traces: Technical Aspects of Positive and Negative Hand-Marking in Rock Art". Arts. 3 (4): 367–393. doi:10.3390/arts3040367.

- ^ a b Dobrez, Patricia (December 2013). "The Case for Hand Stencils and Prints as Proprio-Performative". Arts. 2 (4): 273–327. doi:10.3390/arts2040273.

- ^ Clottes, Jean; Martin, Oliver Y.; Martin, Robert D. (2016). What is Paleolithic Art?. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226188065.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-26663-3. LCCN 2015029149.

- ^ Moore (2017), p. 102

- ^ Podestá, María Mercedes (2002). "Cueva de las Manos as an example of cultural-natural heritage hybrids" (PDF). In Gauer-Lietz, Sieglinde (ed.). Nature and Culture: Ambivalent Dimensions of our Heritage Change of Perspective. Deutsche Unesco-Kommission. Bonn, Germany. pp. 128–129. ISBN 3-927907-84-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Beresford, Matthew (2013). The white devil: the werewolf in European culture. London: Reaktion Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-78023-205-8. OCLC 861693363.

- ^ Raymond, Robert; Thorne, Alan; Buckley, Anthony (1989). Roads Without Wheels (DVD). Man on the Rim: The Peopling of the Pacific. Falls Church, VA: Landmark Media. 14 minutes in. OCLC 664751633.

There are some animals here too. Paintings probably intended to increase the numbers of animals that could be hunted.

- ^ a b Moore (2017), p. 98

- ^ Fiore (2008), pp. 313 & 315

- ^ a b Dobrez, Livio; Dobrez, Patricia (2014). "Canonical Figures and the Recognition of Animals in Life and Art". Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino. 19 (1): 9–22. doi:10.4067/s0718-68942014000100002.

- ^ Aschero (2018), p. 234: "It is very likely that the great eruption of the Hudson volcano around 6720/6625 BP . . . effectively marked the ending of SGA [Styalistic Group A] in the Alto Rio Pinturas and the high Andean lands."

- ^ Aschero (2018), p. 220

- ^ Brook, George A.; Franco, Nora V.; Cherkinsky, Alexander; Acevedo, Agustín; Fiore, Dánae; Pope, Timothy R.; Weimar, Richard D.; Neher, Gregory; Evans, Hayden A.; Salguero, Tina T. (October 2018). "Pigments, binders, and ages of rock art at Viuda Quenzana, Santa Cruz, Patagonia (Argentina)". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 21: 47–63. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.01.004. PII S2352409X17306193.

- ^ Menon (2010), p. 242

- ^ Bernhardson (2014), p. 385

- ^ Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome (2018). "Feeling Stone". SubStance. 47 (2): 23–35. Project MUSE 701284.

- ^ Troncoso, Andrés; Armstrong, Felipe; Basile, Mara (2017). "Rock Art in Central and South America". In David, Bruno; McNiven, Ian J (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190607357.013.53. ISBN 978-0-19-060735-7.

- ^ Loomis, Jenna (November 2018). "'People did great things with their hands': Telling Stories to Engage with Culture". WOW Stories. hdl:10150/651275.

- ^ a b c Podestá, María Mercedes; Strecker, Matthias (2014). "South American Rock Art". Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. pp. 6828–6841. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1623. ISBN 978-1-4419-0426-3.

- ^ a b Keeling, Stephen; Meghji, Shafik; Moseley-Williams, Sorrel; Triebe, Madelaine (2019). The Rough Guide to Argentina (7th ed.). Rough Guides. p. 494. ISBN 978-1-789-19461-6. LCCN 2005209439. OCLC 1112379178.

- ^ a b c d Strecker, Matthias; Pilles, Peter J. (January 2005). "Administration of parks with rack art: A symposium and workshop in Jujuy Argentina, December 2003". Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites. 7 (1): 52–55. doi:10.1179/135050305793137585. S2CID 109586686.

- ^ Strecker, M.; Podestá, M.M. (January 2006), Saiz-Jimenez, C. (ed.), "Rock Art Preservation in Bolivia and Argentina" (PDF), COALITION: CSIC Thematic Network on Cultural Heritage. Electronic Newsletter, no. 11, pp. 5–10, OCLC 972288456, S2CID 201825304

- ^ Gustafsson, Anders; Karlsson, Håkan (2014). "Authenticity and the construction of existential identity: Examples from World Heritage classified rock art sites". In Alexandersson, Henrik; Andreef, Alexander; Bünz, Annika (eds.). Med hjärta och hjärna: en vänbok till professor Elisabeth Arwill-Nordbladh. GOTARC Series A, Gothenburg Archaeological Studies. Vol. 5. Goteborg: Goteborgs Universitet, Institutionen for historiska studier. p. 641. ISBN 978-91-85245-57-7. OCLC 904568027.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Endere, María Luz (January–December 2001). "Patrimonio arqueológico en Argentina. Panorama actual y perspectivas futuras" [Archaeological Heritage in Argentina. Current Situation and Perspectives for the Future]. Revista de Arqueología Americana (in Spanish) (20). Instituto Panamericano de Geografica e Historia: 143–158. JSTOR 27768449. Gale A87703543.

Bibliography

- Orquera, Luis Abel (December 1987). "Advances in the archaeology of the Pampa and Patagonia". Journal of World Prehistory. 1 (4): 333–413. doi:10.1007/BF00974880. JSTOR 25800531. S2CID 161730330.

- Mena, Francisco; McEwan, Colin; Borrero, Luis Alberto (1997). McEwan, Colin; Borrero, Luis Alberto; Prieto, Alfredo (eds.). Patagonia: natural history, prehistory, and ethnography at the uttermost end of the earth. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400864768. ISBN 978-1-4008-6476-8. JSTOR j.ctt7ztms2. OCLC 889252383.

- Fiore, Dánae (2008). "Art on the rocks: Argentina, 2000–2004". In Bahn, Paul G.; Franklin, Natalie R.; Strecker, Matthias (eds.). Rock art studies: news of the world. Vol. 3. Paul G. Bahn, Natalie R. Franklin, Matthias Strecker. Oxford: Oxford Books. ISBN 978-1-78297-590-8. JSTOR j.ctt1cd0p65. OCLC 908040896.

- Menon, Jayashree, ed. (2010). Argentina. Eyewitness Travel Guides. Contributers: Wayne Bernhardson, Declan McGarvey, Chris Moss (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-75666-193-9. OCLC 741938981.

- Bernhardson, Wayne (2014). McLain, Kevin (ed.). Patagonia (4th ed.). Berkeley, CA: Moon Publications. pp. 383–384. ISBN 978-1-61238-912-7. OCLC 897447154.

- Schobinger, Juan (2016-12-05). The Ancient Americans: a reference guide to the art, culture, and history of pre-Columbian North and South America. Vol. 1. Translated by Evans-Corrales, Carys (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/978131570375. ISBN 978-0-7656-8034-1. OCLC 967392115.

- Moore, Jerry D. (2017). Incidence of travel: recent journeys in ancient South America. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. doi:10.5876/9781607326007. ISBN 978-1-60732-600-7. JSTOR j.ctt1m3210q. LCCN 2016053403. OCLC 973325343.

- Aschero, Carlos A. (2018). "Hunting scenes in Cueva de las Manos: Styles, content and chronology (Río Pinturas, Santa Cruz – Argentinian Patagonia)". In Troncoso, Andrés; Armstrong, Felipe; Nash, George (eds.). Archaeologies of rock art: South American Perspectives. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315232782-9. ISBN 9781138292673. OCLC 975369942. S2CID 189442969.

Further reading

- Aschero, Carlos A. "Las escenas de caza en Cueva de las Manos: una perspectiva regional (Santa Cruz, Argentina)". (in Spanish). L’Art Pléistocène dans le Monde (2012): 140–141.

- Gradin, Carlos J.; Aguerre, Ana M.; Mattar, Munir (1995). Cueva de las Manos: Perito Moreno, Provincia de Santa Cruz (Argentina) /[este folleto ha sido redactado por Carlos J. Gradin, Ana M. Aguerre y Munir C. Mattar. (in Spanish). Hotel Belgrano. OCLC 978195249.

- Gradin, C.J. & A.M. Aguerre (1994). Contribución a la Arqueología del Río Pinturas. (in Spanish). Santa Cruz Province. Concepción del Uruguay, Arg.: Búsqueda de Ayllu.

- Gradin, C. J. (1983). "El arte rupestre de la cuenca del Río Pinturas, Provincia de Santa Cruz, República Argentina", Acta praehistorica, 2

- Aguerre, Ana M. (1977). "Nuevo fechado radiocarbónico para la Cueva de las Manos (Santa Cruz)". Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología. 11. hdl:10915/25256.

- Gradin, Carlos J.; Aschero, Carlos; Aguerre, Ana M. (1976). "Investigaciones arqueológicas en la Cueva de las Manos, Alto Río Pinturas, Santa Cruz". Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología. tomo 10. hdl:10915/25285. OCLC 696124191.

- Gradin, C. J.; Aschero, C.A.; & Aguerre, A. M. (1977). "Investigaciones arqueológicas en la Cueva de las Manos (Alto Río Pinturas, Santa Cruz)" (in Spanish). Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología. 10: 201–270.

- Arte y paisaje en cueva de las manos. Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano: Secretaría de Cultura de la Presidencia de la Nación. 1999. ISBN 978-987-95383-8-8. LCCN 2003429491. OCLC 61687026.

- Jorge Prelorán (1971/1981). Manos Pintadas (Painted Hands) (film)

External links

- Cueva de las Manos Website (in Spanish)

- Cueva de las Manos, cave 3D model (Skechfab)

- Cueva de las Manos, Perito Moreno, images (in Spanish)

- Cave of Hands, Perito Moreno, images

- Cueva de los Manos, images

- Nomination file 936

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021

- 10th-millennium BC establishments

- 1941 archaeological discoveries

- Archaeological sites in Argentina

- World Heritage Sites in Argentina

- Protected areas of Santa Cruz Province, Argentina

- Caves of Argentina

- Former populated places in Argentina

- Rock art in South America

- Indigenous painting of the Americas

- Pre-Columbian art

- Archaic period in the Americas

- Indigenous culture of the Southern Cone

- Pre-Clovis archaeological sites in the Americas

- National Historic Monuments of Argentina

- Tourist attractions in Santa Cruz Province, Argentina