Mozambique

This article needs to be updated. |

Republic of Mozambique República de Moçambique | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Estamos Juntos | |

| Anthem: Pátria Amada (formerly Viva, Viva a FRELIMO) | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Maputo |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Government | Republic |

| Armando Guebuza | |

| Luísa Diogo | |

| Independence | |

• from Portugal | June 25 1975 |

• Water (%) | 2.2 |

| Population | |

• July 2005 estimate | 19,792,0001 (54th) |

• 1997 census | 16,099,246 |

| GDP (PPP) | 2005 estimate |

• Total | $27.013 billion (100th) |

• Per capita | $1,389 (158th) |

| HDI (2004) | Error: Invalid HDI value (168th) |

| Currency | Mozambican metical (Mt) (MZM) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (not observed) |

| Calling code | 258 |

| ISO 3166 code | MZ |

| Internet TLD | .mz |

| |

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique (Portuguese: Moçambique or República de Moçambique, pron. IPA: [ʁɛ'publikɐ dɨ musɐ̃'bikɨ]), is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest. It is a member of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries and the Commonwealth of Nations. Mozambique (Moçambique) was named after Muça Alebique, a sultan.

History

Between the first and fourth centuries CE, waves of Bantu-speaking people migrated from the west and north through the Zambezi River valley and then gradually into the plateau and coastal areas. The Bantu were farmers and ironworkers.

When Portuguese explorers reached Mozambique in 1498, Arab commercial and slave trading settlements had existed along the coast and outlying islands for several centuries. From about 1500, Portuguese trading posts and forts became regular ports of call on the new route to the east. Later, traders and prospectors penetrated the interior regions seeking gold and slaves. Although Portuguese influence gradually expanded, its power was limited and exercised through individual settlers and officials who were granted extensive autonomy. As a result, investment lagged while Lisbon devoted itself to the more lucrative trade with India and the Far East and to the colonization of Brazil.

By the early twentieth century the Portuguese had shifted the administration of much of Mozambique to large private companies, like the Mozambique Company, the Zambezi Company and the Niassa Company, controlled and financed mostly by the British, which established railroad lines to neighboring countries and supplied cheap – often forced – African labor to the mines and plantations of the nearby British colonies and South Africa. Because policies were designed to benefit Portuguese immigrants and the Portuguese homeland, little attention was paid to Mozambique's national integration, its economic infrastructure, or the skills of its population.

Post-war period

After World War II, while many European nations were granting independence to their colonies, Portugal maintained that Mozambique and other Portuguese possessions were overseas provinces of the mother country, and emigration to the colonies soared. Calls for Mozambican independence developed apace, and in 1962 several anti-colonial political groups formed the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which initiated an armed campaign against Portuguese colonial rule in September 1964. However, Portugal had occupied the country for more than four hundred years; not all Mozambicans desired independence, and fewer still sought change through armed revolution. Despite arms shipments by China and the Soviet Union, FRELIMO and other loosely linked armed guerilla forces proved no match for Portuguese counterinsurgency forces. After ten years of sporadic warfare, FRELIMO had not made appreciable progress towards capturing either significant amounts of territory or population centers. After a socialist-inspired military coup in Portugal overthrew the dictatorship in 1974, Portugal affirmed its intention to grant independence to its remaining colonies. Mozambique became independent on June 25 1975.

The last thirty years of Mozambique's history have reflected political developments elsewhere in the 20th century. Following the coup in Lisbon, Portuguese withdrew from Mozambique. In Mozambique, the military decision to withdraw occurred within the context of a decade of armed anti-colonial struggle, initially led by American-educated Eduardo Mondlane, who was assassinated in 1969. When independence was achieved in 1975, FRELIMO rapidly established a one-party state allied to the Soviet bloc and outlawed rival political activity. FRELIMO eliminated political pluralism, religious educational institutions, and the role of traditional authorities.

Conflict and civil war

The new government, under president Samora Machel, gave shelter and support to South African (ANC) and Zimbabwean (ZANU) liberation movements while the governments of first Rhodesia and later South Africa (at that time still operating the apartheid laws) fostered and financed an armed rebel movement in central Mozambique called the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO). Hence, civil war, sabotage from neighboring white-ruled states such as Rhodesia and the Apartheid regime of South Africa, and economic collapse characterized the first decade of Mozambican independence. Also marking this period were the mass exodus of Portuguese nationals and Mozambicans of Portuguese heritage, a weak infrastructure, government nationalization of privately owned industries and economic mismanagement. During most of the civil war, the government was unable to exercise effective control outside of urban areas, many of which were cut off from the capital. An estimated 1 million Mozambicans perished during the civil war, 1.7 million took refuge in neighboring states, and several million more were internally displaced. On October 19, 1986 Samora Machel was on his way back from an international meeting in Zambia in the presidential Tupolev Tu-134 aircraft when the plane crashed in the Lebombo Mountains, near Mbuzini. There were nine survivors but President Machel and twenty-four others died, including ministers and officials of the Mozambique government. The United Nations' Soviet delegation issued a minority report contending that their expertise and experience had been undermined by the South Africans. Representatives of the USSR advanced the theory that the plane had been intentionally diverted by a false navigational beacon signal, using a technology provided by military intelligence operatives of the South African government (at that time still operating the laws of apartheid).[1] Machel's successor, Joaquim Chissano, continued the reforms and began peace talks with RENAMO. The new constitution enacted in 1990 provided for a multi-party political system, market-based economy, and free elections. The civil war ended in October 1992 with the Rome General Peace Accords, brokered by the Community of Sant'Egidio. Under supervision of the ONUMOZ peacekeeping force of the United Nations, peace returned to Mozambique.

By mid-1995 the more than 1.7 million Mozambican refugees who had sought asylum in neighboring Malawi, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Zambia, Tanzania, and South Africa as a result of war and drought had returned, as part of the largest repatriation witnessed in Sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, a further estimated four million internally displaced persons returned to their areas of origin.

Foreign relations

While allegiances dating back to the liberation struggle remain relevant, Mozambique's foreign policy has become increasingly pragmatic. The twin pillars of Mozambique's foreign policy are maintenance of good relations with its neighbors and maintenance and expansion of ties to development partners.

During the 1970s and the early 1980s, Mozambique's foreign policy was inextricably linked to the struggles for majority rule in Rhodesia and South Africa as well as superpower competition and the Cold War. Mozambique's decision to enforce UN sanctions against Rhodesia and deny that country access to the sea led Ian Smith's government to undertake overt and covert actions to destabilize the country. Although the change of government in Zimbabwe in 1980 removed this threat, the government of South Africa (at that time still operating under the laws of apartheid) continued to finance the destabilization of Mozambique. It also belonged to the Front Line States.

The 1984 Nkomati Accord, while failing in its goal of ending South African support to RENAMO, opened initial diplomatic contacts between the Mozambican and South African governments. This process gained momentum with South Africa's elimination of apartheid, which culminated in the establishment of full diplomatic relations in October 1993. While relations with neighboring Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania show occasional strains, Mozambique's ties to these countries remain strong.

In the years immediately following its independence, Mozambique benefited from considerable assistance from some western countries, notably the Scandinavians. USSR and its allies, however, became Mozambique's primary economic, military, and political supporters and its foreign policy reflected this linkage. This began to change in 1983; in 1984 Mozambique joined the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Western aid quickly replaced Soviet support, with the Scandinavians countries of Sweden (EU Member since 1996), Norway, Denmark (EU Member since 1973) and Iceland. Plus Finland (EU Member since 1996) and the Netherlands within the European Union are becoming increasingly important sources of development assistance. Italy also maintains a profile in Mozambique as a result of its key role during the peace process. Relations with Portugal, the former colonial power, continue to play an important role as Portuguese investors play a visible role in Mozambique's economy.

Mozambique is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement and ranks among the moderate members of the African Bloc in the United Nations and other international organizations. Mozambique also belongs to the African Union (formerly the Organization of African Unity) and the Southern African Development Community. In 1994, the Government became a full member of the Organization of the Islamic Conference, in part to broaden its base of international support but also to please the country's sizable muslim population. Similarly, in early 1996 Mozambique joined its Anglophone neighbors in the Commonwealth. It is the only nation to join the Commonwealth that was never part of the British Empire. In the same year, Mozambique became a founding member and the first President of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), and maintains close ties with other Lusophone states.

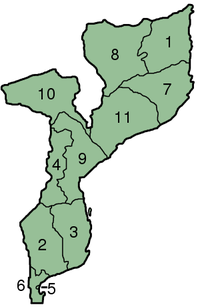

Administrative divisions

Mozambique is divided into ten provinces (provincias) and one capital city (cidade) with provincial status. The provinces are subdivided into 129 districts (distritos).

|

|

Geography

At 309,475 square miles (801,590 km²), Mozambique is the world's 36th-largest country (after Pakistan). It is comparable in size to Turkey, and is somewhat larger than the US state of Texas.

Politics

Mozambique is a multi-party democracy under the 1990 constitution. The executive branch comprises a president, prime minister, and Council of Ministers. There is a National Assembly and municipal assemblies. The judiciary comprises a Supreme Court and provincial, district, and municipal courts. Suffrage is universal at eighteen.

In 1994, the country held its 1st democratic elections. Joaquim Chissano was elected President with 53% of the vote, and a 250-member National Assembly was voted in with 129 FRELIMO deputies, 112 RENAMO deputies, and nine representatives of three smaller parties that formed the Democratic Union (UD). Since its formation in 1994, the National Assembly has made progress in becoming a body increasingly more independent of the executive. By 1999, more than one-half (53%) of the legislation passed originated in the Assembly.

After some delays, in 1998 the country held its first local elections to provide for local representation and some budgetary authority at the municipal level. The principal opposition party, RENAMO, boycotted the local elections, citing flaws in the registration process. Independent slates contested the elections and won seats in municipal assemblies. Turnout was very low.

In the aftermath of the 1998 local elections, the government resolved to make more accommodations to the opposition's procedural concerns for the second round of multiparty national elections in 1999. Working through the National Assembly, the electoral law was rewritten and passed by consensus in December 1998. Financed largely by international donors, a very successful voter registration was conducted from July to September 1999, providing voter registration cards to 85% of the potential electorate (more than seven million voters).

The second general elections were held December 3-5, 1999, with high voter turnout. International and domestic observers agreed that the voting process was well organized and went smoothly. Both the opposition and observers subsequently cited flaws in the tabulation process that, had they not occurred, might have changed the outcome. In the end, however, international and domestic observers concluded that the close result of the vote reflected the will of the people.

President Chissano won the presidency with a margin of 4% points over the RENAMO-Electoral Union coalition candidate, Afonso Dhlakama, and began his five-year term in January 2000. FRELIMO increased its majority in the National Assembly with 133 out of 250 seats. RENAMO-UE coalition won 116 seats, one went independent, and no third parties are represented.

The opposition coalition did not accept the National Election Commission's results of the presidential vote and filed a formal complaint to the Supreme Court. One month after the voting, the court dismissed the opposition's challenge and validated the election results. The opposition did not file a complaint about the results of the legislative vote.

The second local elections, involving thirty-three municipalities with some 2.4 million registered voters, took place in November 2003. This was the first time that FRELIMO, RENAMO-UE, and independent parties competed without significant boycotts. The 24% turnout was well above the 15% turnout in the first municipal elections. FRELIMO won twenty-eight mayoral positions and the majority in twenty-nine municipal assemblies, while RENAMO won five mayoral positions and the majority in four municipal assemblies. The voting was conducted in an orderly fashion without violent incidents. However, the period immediately after the elections was marked by objections about voter and candidate registration and vote tabulation, as well as calls for greater transparency.

In May 2004, the government approved a new general elections law that contained innovations based on the experience of the 2003 municipal elections.

Presidential and National Assembly elections took place on December 1-2, 2004. FRELIMO candidate Armando Guebuza won with 64% of the popular vote. His opponent, Afonso Dhlakama of RENAMO, received 32% of the popular vote. FRELIMO won 160 seats in Parliament. A coalition of RENAMO and several small parties won the 90 remaining seats. Armando Guebuza was inaugurated as the President of Mozambique on February 2, 2005. RENAMO and some other opposition parties made claims of election fraud and denounced the result. These claims were supported by international observers (among others by the European Union Election Observation Mission to Mozambique and the Carter Center) to the elections who criticized the fact that the National Electoral Commission (CNE) did not conduct fair and transparent elections. They listed a whole range of shortcomings by the electoral authorities that benefited the ruling party FRELIMO. However, according to EU observers, the elections shortcomings have probably not affected the final result in the presidential election. On the other hand, the observers have declared that the outcome of the parliamentary election and thus the distribution of seats in the National Assembly does not reflect the will of the Mozambican people and is clearly to the disadvantage of RENAMO.

The Reporters Without Borders' Worldwide Press Freedom Index 2006 ranked Mozambique 45th out of 168 countries.

Economy

This article needs to be updated. |

The official currency is the New Metical (as of 2006, 1 USD is roughly equivalent to 25 Meticals), which on January 1 2007 replaced old Meticals in rate thousand to one. The old currency will be redeemed by the Bank of Mozambique until the end of 2012. US dollar, South African rand and recently also Euro are also widely accepted and used in business transactions. The minimum legal salary is around 60 dollars per month. Mozambique is member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC). The SADC free trade protocol is aimed at making the South African region more competitive by eliminating tariffs and other trade barriers.

Rebounding growth

The resettlement of war refugees and successful economic reform have led to a high growth rate: the average growth rate from 1993 to 1999 was 6.7%; from 1997 to 1999 it averaged more than 10% per year. The devastating floods of early 2000 slowed GDP growth to 2.1%. A full recovery was achieved with growth of 14.8% in 2001. In 2003, the growth rate was 7%. The government projects the economy to continue to expand between 7%-10% a year for the next five years, although rapid expansion in the future hinges on several major foreign investment projects, continued economic reform, and the revival of the agriculture, transportation, and tourism sectors. More than 75% of the population engages in small scale agriculture, which still suffers from inadequate infrastructure, commercial networks, and investment. However, 88% of Mozambique's arable land is still uncultivated.

Inflation

The government's tight control of spending and the money supply, combined with financial sector reform, successfully reduced inflation from 70% in 1994 to less than 5% in 1998-99. Economic disruptions stemming from the devastating floods of 2000 caused inflation to jump to 12.7% that year, and it was 13% in 2003. The Mozambique's currency, the Metical, devaluated by 50% to the dollar in 2001, although in late 2001 it began to stabilize. Since then, it has held steady at about 24,000 MZN to 1 U.S. dollar. New Metical replaced old Meticals in rate thousand to one on January 1 2007 bringing the exchange rate to 25 (new) MZN to 1 USD.

Economic reforms

More than 1,200 state-owned enterprises (mostly small) have been privatized. Preparations for privatization and/or sector liberalization are underway for the remaining parastatal enterprises, including telecommunications, energy, ports, and the railroads. The government frequently selects a strategic foreign investor when privatizing a parastatal. Additionally, customs duties have been reduced, and customs management has been streamlined and reformed. The government introduced a value-added tax in 1999 as part of its efforts to increase domestic revenues. Plans for 2003-04 include Commercial Code reform; comprehensive judicial reform; financial sector strengthening; continued civil service reform; and improved government budget, audit, and inspection capability.[citation needed]

Improving trade imbalance

Imports remain almost 40% greater than exports, but this is a significant improvement over the 4:1 ratio of the immediate post-war years. In 2003, imports were $1.24 billion and exports were $910 million. Support programs provided by foreign donors and private financing of foreign direct investment mega-projects and their associated raw materials, have largely compensated for balance-of-payments shortfalls. The medium-term outlook for exports is encouraging, since a number of foreign investment projects should lead to substantial export growth and a better trade balance. MOZAL, a large aluminum smelter that commenced production in mid-2000, has greatly expanded the nation's trade volume. Traditional Mozambican exports include cashews, shrimp, fish, copra, sugar, cotton, tea, and citrus fruits. Most of these industries are being rehabilitated. As well, Mozambique is less dependent on imports for basic food and manufactured goods because of steady increases in local production.

Demographics

The north-central provinces of Zambezia and Nampula are the most populous, with about 45% of the population. The estimated four million Makua are the dominant group in the northern part of the country; the Sena and Shona (mostly Ndau) are prominent in the Zambezi valley, and the Shangaan (Tsonga) dominate in southern Mozambique. Other groups include Makonde, Yao, Swahili, Tonga, Chopi, and Nguni (including Zulu). Bantu people comprise 99.66% of the population, the remaining 0.34% include Europeans 0.06% (largely of Portuguese ancestry), Euro-Africans 0.2% (mestiço people of mixed Bantu and Portuguese heritage), and Indians 0.08%.[2] During Portuguese colonial rule, a large minority of people of Portuguese descent lived permanently in almost all areas of the country, and Mozambicans with Portuguese blood at the time of independence numbered about 250,000. Most of these left the region after its freedom in 1975. The remaining minorities in Mozambique claim heritage from Pakistan, Portuguese India and Arab countries. There are also some 7,000 Chinese.

Despite the influence of Islamic coastal traders and European colonizers, the people of Mozambique have largely retained an indigenous culture based on small-scale agriculture. Mozambique's most highly developed art forms have been wood sculpture, for which the Makonde in northern Mozambique are particularly renowned, and dance. The middle and upper classes continue to be heavily influenced by the Portuguese colonial and linguistic heritage.

Portuguese is the official and most widely spoken language of the nation, because Bantus speak several of their different languages (most widely used of these are Swahili, Makhuwa, Sena, Ndau, and Shangaan — these have many Portuguese-origin words), but 40% of all people speak it — 33.5%, mostly Bantus, as their second language and only 6.5%, mostly white Portuguese and mestiços, speak it as their first language. Arabs, Chinese, and Indians speak their own languages (Indians from Portuguese India speak any of the Portuguese Creoles of their origin) aside from Portuguese as their second language. Most educated Mozambicans speak English, which is used in schools and business as second or third language.

Education

Under Portuguese rule, educational opportunities for poor Mozambicans were limited; Most of the Bantu population was illiterate, and many could not speak Portuguese. In fact, most of today's political leaders were educated in missionary schools. After independence, the government placed a high priority on expanding education, which reduced the illiteracy rate to about two-thirds as primary school enrollment increased. Unfortunately, in recent years school construction and teacher training enrollments have not kept up with population increases. With post-war enrollments reaching all-time highs, the quality of education has suffered. All Mozambicans are required by law to attend school through the primary level. After grade 7, students must take standardized national exams to enter secondary school, which runs from 8th to 10th grade. Secondary school students study Portuguese, Mathematics, Biology, Chemistry, Physics, History, Geography, Physical Education, Technical Drawing, and English (which all schoolchildren begin in grade 6). Another round of national exams after grade 10 allows passage into pre-university school (grades 11 and 12), in which students have the opportunity to study all of the former subjects (minus Physical Education) plus Philosophy and French. Space in Mozambican universities is extremely limited; thus most students who complete pre-university school do not immediately proceed onto university studies. Many go to work as teachers or are unemployed. There are also institutes specializing in agricultural, technical, or pedagogical studies which students may attend after grade 10 in lieu of a pre-university school, which give more practical educations.

Religion

According to the 1997 Second General Population and Housing Census, the religions of the polled population were as follows: 24.2% identified themselves as Roman Catholic; 24.25% claimed to not be affiliated with a religion; 18.7% adhering to Zionism (an African form of Christianity); 17.8% of the population were cited as Muslims; 11.45% as other non-Catholic Christians; 3.6% as "other".

The Roman-Catholic church has established twelve dioceses (Beira, Chimoio, Gurué, Inhambane, Lichinga, Maputo, Nacala, Nampula, Pemba, Quelimane, Tete, and Xai-Xai - archdioceses are Beira, Maputo and Nampula). Statistics for the dioceses range from a low 7.44% Catholics in the population in the diocese of Chimoio, to 87.50% in Quelimane diocese (2006 official Catholic figures).

Muslims are particularly present in the North of the country. They are organised in several "tariqa" or brotherhoods (of the Qadiriya or Shadhuliyyah branch). Two national organisation also exist - the Conselho Islamico de Mocambique (reformists) and the Congresso Islamico de Mocambique (pro-sufi). There are also important Indo-Pakistani associations as well as some Shia and particularly Ismaili communities.

Among the main Protestant churches are Igreja União Baptista de Moçambique, the Assembleias de Deus, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Anglican Church of Mozambique, the Igreja do Evangelho Completo de Deus, the Igreja Metodista Unida, the Igreja Presbiteriana de Moçambique, the Igreja de Cristo and the Assembleia Evangélica de Deus. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is also present as well as the Jehovah's Witnesses and the Brazilian Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus.[citation needed]

Music

Mozambique has distinct styles of music and distinct patterns of use of instruments. Some of the music styles fall into the classification of Lusophone musical culture.

See also

- List of Mozambique-related topics

- Communications in Mozambique

- Liga dos Escuteiros de Moçambique

- List of conservation areas of Mozambique

- Military of Mozambique

- Public holidays in Mozambique

- Transport in Mozambique

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

- ^ "Special Investigation into the death of President Samora Machel". [[Truth and Reconciliation Commission (South Africa)|]] Report, vol.2, chapter 6a. Retrieved June 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mozambique". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

Bibliography

- Abrahamsson, Hans Mozambique: The Troubled Transition, from Socialist Construction to Free Market Capitalism London: Zed Books, 1995

- Cahen, Michel Les bandits: un historien au Mozambique_, Paris: Gulbenkian, 1994

- Pitcher, Anne Transforming Mozambique: The politics of privatisation, 1975–2000 Cambridge, 2002

- Newitt, Malyn A History of Mozambique Indiana University Press

- Varia, "Religion in Mozambique", LFM: Social sciences & Missions No. 17, Dec. 2005

External links

Government

- Republic of Mozambique Official Government Portal

- Health Ministry

- Science and Technology Portal

- National Petroleum Institute

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística The National Statistical Office

Observing politics

News

- The Mozambique News Agency - AIM Reports

- Agência de Informação de Moçambique

- Independent Weekly from Maputo in Portuguese

- Independent Newspaper from Maputo in Portuguese

- Indian Ocean Newsletter - Mozambique

Forums

- The most popular Forum in Mozambique

- MozamBIG-Forum.com - The best place to discuss Mozambique (in Portuguese)

- Imensis Comunity Forum

Overviews

- BBC News Country Profile - Mozambique

- CIA World Factbook - Mozambique

- Mozambique's location on a 3D globe (Java)

Directories

- Open Directory Project - Mozambique directory category

- Stanford University - Africa South of the Sahara: Mozambique directory category

- The Index on Africa - Mozambique directory category

- University of Pennsylvania - African Studies Center: Mozambique directory category

- Yahoo! - Mozambique directory category

- Business Anti-Corruption Portal Mozambique Country Profile