Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also called the Roman alphabet, is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world today.

Letters of the alphabet

As used in modern English, the Latin alphabet consists of the following characters (cf. English alphabet):

| Majuscule FormsTemplate:Ref 1 | ||||||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M |

| N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| Minuscule FormsTemplate:Ref 2 | ||||||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m |

| n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

- The majuscule forms are also called uppercase or capital letters.

- The minuscule forms are also called lowercase or small letters.

Other letters

The ligatures Æ, Œ, and the symbol ß, when used in English, French, or German, are normally not counted as separate alphabetic letters but as variants of AE, OE, and ss, respectively. Letters bearing diacritics are also not counted as separate letters in these languages. This is often not the case for Æ and Œ and some letters bearing diacritics in other variations of the Latin alphabet. For example, å, ä, and ö all count as separate letters in Swedish.

The letters Þþ (thorn), Ðð (eth), Ææ (ash) and Ƿƿ (wynn) are no longer a part of the Latin alphabet as used in English, but they were considered Latin letters in the past. Except for the last, they are still used in Icelandic. For a short time in Roman history, the three Claudian letters were added to the alphabet, but they were not widely received and were eventually removed.

Evolution

| A | B | C | D | E | F | Z |

| H | I | K | L | M | N | O |

| P | Q | R | S | T | V | X |

- See Alphabet: History and diffusion for the history of alphabets leading up to the Roman alphabet.

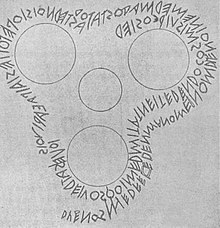

It is generally held that the Latins adopted the western variant of the Greek alphabet in the 7th century BC from Cumae, a Greek colony in southern Italy. From the Cumae alphabet, the Etruscan alphabet was derived and the Latins finally adopted 21 of the original 26 Etruscan letters.

The original Latin alphabet was:

- C stood for both g and k.

- I stood for both i and j.

- V stood for both u and v.

Later the Z was dropped and a new letter G was placed in its position. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters was short-lived, but after the conquest of Greece in the first century BC the letters Y and Z were, respectively, adopted and readopted from the Greek alphabet and placed at the end. Now the new Latin alphabet contained 23 letters:

| Symbol: | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

| Latin name of letter: | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ex | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin name (IPA): | [aː] | [beː] | [keː] | [deː] | [eː] | [ɛf] | [geː] | [haː] | [iː] | [kaː] | [ɛl] | [ɛm] | [ɛn] | [oː] | [peː] | [kuː] | [ɛr] | [ɛs] | [teː] | [uː] | [ɛks] | [iː 'graɪka] | ['zeːta] |

The Latin names of some of the letters are disputed. In general, however, the Romans did not use the traditional (Semitic-derived) names as in Greek: the names of the stop consonant letters were formed by adding [eː] to the sound (except for C, K, and Q which needed different vowels to distinguish them) and the names of the continuants consisted either of the bare sound, or the sound preceded by [ɛ]. The letter Y when introduced was probably called hy [hyː] as in Greek (the name upsilon being not yet in use) but was changed to i Graeca ("Greek i") as the [i] and [y] sounds merged in Latin. Z was given its Greek name, zeta. For the Latin sounds represented by the various letters see Latin spelling and pronunciation; for the names of the letters in English see English alphabet.

Medieval and later developments

It was not until the Middle Ages that the letter J (representing non-syllabic I) and the letters U and W (to distinguish them from V) were added.

The alphabet used by the Romans consisted only of capital (upper case or majuscule) letters. The lower case (minuscule) letters developed in the Middle Ages from cursive writing, first as the uncial script, and later as minuscule script. The old Roman letters were retained for formal inscriptions and for emphasis in written documents. The languages that use the Latin alphabet generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and for proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages vary in their rules for capitalization. Old English and modern English of the 18th century, for example, used to capitalise all nouns, in the same way that Modern German does today, e.g., "All the Sisters of the old Town had seen the Birds."

Spread of the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet spread from Italy, along with the Latin language, to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Roman Empire, including Greece, Asia Minor, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half of the Empire, and as the western Romance languages, including Spanish, French, Catalan, Portuguese and Italian, evolved out of Latin they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet. The Latin alphabet spread to the Germanic peoples of northern Europe with the spread of western Christianity, displacing the earlier Runic alphabets. During the Middle Ages the Latin alphabet also came into use among the western Slavic peoples, including the Poles, Czechs, Croats, Slovenes, and Slovaks, as these nations adopted Roman Catholicism; the eastern Slavs generally adopted both Orthodox Christianity and the Cyrillic alphabet. The Baltic Lithuanians and Latvians, as well as the non-Indo-European Finns, Estonians, and Hungarians, also adopted the Latin alphabet.

As late as 1492, the Latin alphabet was limited primarily to the nations of western and central Europe. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of eastern and southern Europe mostly used the Cyrillic alphabet, and the Greek alphabet was still in use by Greek-speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic alphabet was widespread within Islam, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Over the past 500 years, the Latin alphabet has spread around the world. It spread to the Americas, Australia, and parts of Asia, Africa, and the Pacific with European colonization, along with the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, and Dutch languages. In the late eighteenth century, the Romanians adopted the Latin alphabet; although Romanian is a Romance language, the Romanians were predominantly Orthodox Christians, and until the nineteenth century the Church used the Cyrillic alphabet. Vietnam, under French rule, adapted the Latin alphabet for use with the Vietnamese language, which had previously used Chinese characters. The Latin alphabet is also used for many Austronesian languages, including Tagalog and the other languages of the Philippines, and the official Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets. In 1928, as part of Kemal Atatürk's reforms, Turkey adopted the Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing the Arabic alphabet. Most of Turkic-speaking peoples of the former USSR, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz etc. used the Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s. In the 1940s all those alphabets were replaced by Cyrillic. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, several of the newly-independent Turkic-speaking republics adopted the Latin alphabet, replacing Cyrillic. Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan have officially adopted the Latin alphabet for Azeri, Uzbek, and Turkmen, respectively. In the 1970s, the People's Republic of China developed an official transliteration of Mandarin Chinese into the Latin alphabet, called Pinyin, although use of Chinese characters is still predominant.

Use in other languages

In the course of its history, the Latin alphabet was adapted for use for new languages, some of which had phonemes which were not used in languages previously written with this alphabet, and therefore diacritics and new letters were created as needed.

Diacritics

- the cedilla in ç, originally a small z written below the c (once symbolized /ts/ in Romance languages, now gives c a 'soft' sound before a, o, and u, for example, /s/ in French façade, Portuguese Caçar and in Catalan Barça).

- the caron in č š ž (used in Baltic and Slavic languages to mark post-alveolar versions of the base phoneme).

- the tilde in Spanish ñ, Portuguese ã and õ, Estonian õ. In Portuguese, it was originally a small n written above the letter (once used to mark the elision of a former n, now marks nasalization of the base letter). In Estonian, õ is considered a separate letter of the alphabet.

- the acute accent in á é í ó ú in Portuguese, Spanish and other languages.

- the grave accent in à è ì ò ù in French, Italian, Portuguese and other languages.

- the circumflex in the vowels â ê î ô û in French, Portuguese, Romanian, and other languages, and in the consonants ĉ ĝ ĥ ĵ ŝ in Esperanto.

- the umlaut in ä ö ü in German and other languages, and ë in Albanian, which changes the quality (sound) of the vowel. In German, this mark was formerly written as a small e over the affected vowel. Modern German spelling accepts ae oe and ue as variants when the umlaut is unavailable.

- the diaeresis (same visual appearance as the umlaut above) in ä ë ï ö ü in several languages (to indicate that two successive vowels do not form a diphthong).

- the dot above in ċ ġ ż in Maltese and ż in Polish and ė in Lithuanian.

- the ogonek in ą ę į ų in Polish and Lithuanian.

- the macron in ā ē ī ō ū in Latvian, Māori and romanized Japanese.

- the double acute accent in ő ű in Hungarian, representing long versions of the umlauted vowels ö and ü.

- the comma underneath, as used in ş and ţ in Romanian (often rendered less than optimally in fonts as a cedilla). Also used for ķ ļ ņ ŗ in Latvian.

There are other diacritics and other uses for the ones described here. Please see Alphabets derived from the Latin for a more complete list.

New Letterforms

W is a letter made up from two V's or U's. It was added in late Roman times to represent a Germanic sound. The letters U and J, similarly, were originally not distinguished from V and I, respectively. In Old English, ash æ, eth ð and the Runic letters thorn þ, and wynn ƿ were added. Eth and thorn were replaced with 'th', and wynn with the new letter 'w'. In modern Icelandic, thorn and eth are still used. The additional letters added in German are special presentations of earlier ligature forms (ae → ä, ue → ü or ſs → ß). French adds the circumflex to record elided consonants that were present in earlier forms and are often still present in the modern English cognate forms (Old French hostel → French hôtel = English hotel or Late Latin pasta → Middle French paste → English paste. Note Modern French divergence to pâte, and preservation of the original pasta in Italian, and now borrowed into English).

West Slavic and most South Slavic languages use the Latin alphabet rather than the Cyrillic, a reflection of the dominant religion practiced among those peoples. Among these, Polish uses a variety of diacritics and digraphs to represent special phonetic values, as well as the l with stroke - ł - for a sound similar to w. Czech uses diacritics as in Dvořák — the term háček (caron) originates from Czech. Croatian and the Latin version of Serbian use carons in č, š, ž, an acute in ć and a bar in đ. The languages of Eastern Orthodox Slavs generally use Cyrillic instead which is much closer to the Greek alphabet. The Serbian language uses two alphabets.

The African language Hausa uses three additional consonant letters: ɓ, ɗ and ƙ, which are variants of b, d and g employed by linguists to represent certain sounds similar to them.

Collating in other languages

Alphabets derived from the Latin have varying collating rules:

- In Breton, there is no "c" but there are the ligatures "ch" and "c'h", which are collated between "b" and "d". For example: « buzhugenn, chug, c'hoar, daeraouenn » (earthworm, juice, sister, teardrop).

- In Croatian and Serbian and related South Slavic languages, the five accented characters and two conjoined characters are sorted after the originals: ..., C, Č, Ć, D, DŽ, Đ, E, ..., L, LJ, M, N, NJ, O, ..., S, Š, T, ..., Z, Ž.

- In Czech and Slovak, accented vowels have secondary collating weight - compared to other letters, they are treated as their unaccented forms (A-Á, E-É-Ě, I-Í, O-Ó-Ô, U-Ú-Ů, Y-Ý), but then they are sorted after the unaccented letters (for example, the correct lexicographic order is baa, baá, báa, bab, báb, bac, bác, bač, báč). Accented consonants (the ones with caron) have primary collating weight and are collocated immediately after their unaccented counterparts, with exception of Ď, Ň and Ť, which have again secondary weight. CH is considered to be a separate letter and goes between H and I. In Slovak, DZ and DŽ are also considered separate letters and are positioned between Ď and E (A-Á-Ä-B-C-Č-D-Ď-DZ-DŽ-E-É…).

- In the Danish and Norwegian alphabets, the same extra vowels as in Swedish (see below) are also present but in a different order and with different glyphs (..., X, Y, Z, Æ, Ø, Å). Also, "Aa" collates as an equivalent to "Å". The Danish alphabet has traditionally seen "W" as a variant of "V", but nowadays "W" is considered a separate letter.

- In Dutch the combination IJ (representing IJ (letter IJ)) was formerly to be collated as Y (or sometimes, as a separate letter Y < IJ < Z), but is currently mostly collated as 2 letters (II < IJ < IK). Exceptions are phone directories; IJ is always collated as Y here because in many Dutch family names Y is used where modern spelling would require IJ. Note that a word starting with ij that is written with a capital I is also written with a capital J, for example, the town IJmuiden (mun. Velsen) and the river IJssel.

- In Esperanto, consonants with circumflex accents (ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ), as well as ŭ (u with breve), are counted as separate letters and collated separately (c, ĉ, d, e, f, g, ĝ, h, ĥ, i, j, ĵ ... s, ŝ, t, u, ŭ, v, z).

- The Faroese alphabet also has some of the Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish extra letters, namely Æ and Ø. Furthermore, the Faroese alphabet uses the Icelandic eth, which follows the D. Five of the six vowels A, I, O, U and Y can get accents and are after that considered separate letters. The consonants C, Q, X, W and Z are not found. Therefore the first five letters are A, Á, B, D and Ð, and the last five are V, Y, Ý, Æ, Ø

- In Filipino and other Philippine languages, the letter Ng is treated as a separate letter. Also, letter derivatives (such as Ñ) immediately follow the base letter. Filipino also is written with accents and other marks, but the marks are not in very wide use (except the tilde). It is pronounced as in sing, ping-pong, etc. By itself, it is pronounced nang, but in general Philippine orthography, it is spelled as if it were two separate letters (n and g). (Philippine orthography also includes spelling.)

- The Finnish alphabet and collating rules are the same as in Swedish, except for the addition of the letters Š and Ž, which are considered variants of S and Z.

- In French and English, characters with diaeresis (ä, ë, ï, ö, ü, ÿ) are usually treated just like their un-accented versions. If two words differ only by an accent in French, the one with the accent is greater. (However, the Unicode 3.0 book specifies a more complex traditional French sorting rule for accented letters.)

- In German letters with umlaut (Ä, Ö, Ü) are treated generally just like their non-umlauted versions; ß is always sorted as ss. This makes the alphabetic order Arg, Ärgerlich, Arm, Assistent, Aßlar, Assoziation. For phone directories and similar lists of names, the umlauts are to be collated like the letter combinations "ae", "oe", "ue". This makes the alphabetic order Udet, Übelacker, Uell, Ülle, Ueve, Üxküll, Uffenbach.

- The Hungarian language has accents, umlauts, and double accents. The accent is ignored in collating, and the double accent, which indicates a long umlaut vowel, is treated as equal to the umlaut.

- In Icelandic, Þ is added, and D is followed by Ð.

- Both letters were also used by Anglo-Saxon scribes who also used the Runic letter Wynn to represent /w/.

- Þ (called thorn; lowercase þ) is also a Runic letter.

- Ð (called eth; lowercase ð) is the letter D with an added stroke.

- In Polish, specifically Polish letters derived from the Latin alphabet are collated after their originals: A, Ą, B, C, Ć, D, E, Ę, ..., L, Ł, M, N, Ń, O, Ó, P, ..., S, Ś, T, ..., Z, Ź, Ż.

- In Romanian, special characters derived from the Latin alphabet are collated after their originals: A, Ă, Â, ..., I, Î, ..., S, Ş, T, Ţ, ..., Z.

- In the Swedish alphabet, "W" is seen as a variant of "V" and not a separate letter. It is however recognised and maintained in names, like in "William". The alphabet also has three extra vowels placed at its end (..., X, Y, Z, Å, Ä, Ö).

- Some languages have more complex rules: for example, Spanish treated (until 1997) "CH" and "LL" as single letters, giving an ordering of CINCO, CREDO, CHISPA and LOMO, LUZ, LLAMA. This is not true anymore since in 1997 RAE adopted the more conventional usage, and now LL is collated between LK and LM, and CH between CG and CI. The only Spanish specific collating question is Ñ (eñe) as a different letter collated after N.

- In Tatar and Turkish, there are 9 additional letters. 5 of them are vowels, paired with main alphabet vowels as hard-smooth: a-ä, o-ö, u-ü, í-i, ı-e. The four remaining are consonants: ş is sh, ç is ch, ñ is ng and ğ is gh.

- Welsh also has complex rules: the combinations CH, DD, FF, NG, LL, PH and TH are all considered single letters, and each is listed after the letter which is the first character in the combination, with the exception of NG which is listed after G. However, the situation is further complicated by these combinations not always being single letters. An example ordering is LAWR, LWCUS, LLONG, LLOM, LLONGYFARCH: the last of these words is a juxtaposition of LLON and GYFARCH, and, unlike LLONG, does not contain the letter NG.

For multilingual situations with no one preferred language or alphabet, the Unicode Collation Algorithm can be used.

See also

- Collation

- Roman square capitals

- Roman cursive

- Alphabets derived from the Latin

- Roman letters used in mathematics

References

- Jensen, Hans. 1970. Sign Symbol and Script. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. Transl. of Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften. 1958, as revised by the author.

- Rix, Helmut. 1993. "La scrittura e la lingua" In: Cristofani, Mauro (hrsg.) 1993. Gli etruschi - Una nuova immagine. Firenze: Giunti. S.199-227.

- Sampson, Geoffrey. 1985. Writing systems. London (etc.): Hutchinson.

- Wachter, Rudolf. 1987. Altlateinische Inschriften: sprachliche und epigraphische Untersuchungen zu den Dokumenten bis etwa 150 v.Chr. Bern (etc.): Peter Lang.

- "The names of the letters of the Latin alphabet" (Appendix C) in W. Sidney Allen. Vox Latina — a guide to the pronunciation of classical Latin. Cambridge University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-5221-22049-1 (Second edition)

- Biktaş, Şamil, 2003, Tuğan Tel.