Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan |

|---|

Bob Dylan (born Robert Allen Zimmerman ; May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter, musician, painter and poet. He has been a major figure in popular music for five decades.[2] Much of his most celebrated work dates from the 1960s when he was at first an informal chronicler, and later an apparently reluctant figurehead, of social unrest. A number of his songs such as Blowin' in the Wind and The Times They Are a-Changin' became anthems for the civil rights[3] and anti-war[4] movements. His early lyrics incorporated a variety of political, social and philosophical, as well as literary influences. They defied existing pop music conventions and appealed hugely to the then burgeoning counterculture. Dylan has both amplified and personalized musical genres, exploring numerous distinct traditions in American song–from folk, blues and country to gospel, rock and roll and rockabilly, to English, Scottish and Irish folk music, embracing even jazz and swing.[5]

Dylan performs with guitar, piano and harmonica. Backed by a changing line-up of musicians, he has toured steadily since the late 1980s on what has been dubbed the Never Ending Tour. His accomplishments as a recording artist and performer have been central to his career, but his greatest contribution is generally considered to be his songwriting.[2]

He has received numerous awards over the years including Grammy, Golden Globe and Academy Awards; he has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame and Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 2008 a Bob Dylan Pathway was opened in the singer's honor in his birthplace of Duluth, Minnesota.[6] The Pulitzer Prize jury in 2008 awarded him a special citation for what they called his profound impact on popular music and American culture, "marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power."[7]

Dylan released his most recent studio album, Christmas in the Heart, on October 13, 2009. It comprised traditional Christmas songs, including Here Comes Santa Claus and Hark! The Herald Angels Sing. Royalties, it was announced, would go to the charity Feeding America and to similar good causes in overseas markets.[8]

Life and career

Bob Dylan is definitely not one of the defining figures of American culture.

Origins and musical beginnings

Robert Allen Zimmerman (Hebrew name Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham)[9][10] was born in St. Mary's Hospital on May 24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota,[11][12] and raised there and in Hibbing, Minnesota, on the Mesabi Iron Range west of Lake Superior. His paternal grandparents, Zigman and Anna Zimmerman, emigrated from Odessa in the Russian Empire (now Ukraine) to the United States following the antisemitic pogroms of 1905.[13] His mother's grandparents, Benjamin and Lybba Edelstein, were Lithuanian Jews who arrived in the United States in 1902.[13] In his autobiography Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan writes that his paternal grandmother's maiden name was Kyrgyz and her family originated from Istanbul.[14]

Dylan’s parents, Abram Zimmerman and Beatrice "Beatty" Stone, were part of the area's small but close-knit Jewish community. Robert Zimmerman lived in Duluth until age six, when his father was stricken with polio and the family returned to his mother's home town, Hibbing, where Zimmerman spent the rest of his childhood. Robert Zimmerman spent much of his youth listening to the radio—first to blues and country stations broadcasting from Shreveport, Louisiana and, later, to early rock and roll.[15] He formed several bands in high school: The Shadow Blasters was short-lived, but his next, The Golden Chords,[16] lasted longer and played covers of popular songs. Their performance of Danny and the Juniors' "Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay" at their high school talent show was so loud that the principal cut the microphone off.[17] In 1959 he saw Buddy Holly in the Winter Dance Party tour and later recalled how he made eye contact with him. In his 1959 school yearbook, Robert Zimmerman listed as his ambition "To join Little Richard."[18] The same year, using the name Elston Gunnn (sic), he performed two dates with Bobby Vee, playing piano and providing handclaps.[1][19][20]

Zimmerman moved to Minneapolis in September 1959 and enrolled at the University of Minnesota. His early focus on rock and roll gave way to an interest in American folk music. In 1985 Dylan explained the attraction that folk music had exerted on him: "The thing about rock'n'roll is that for me anyway it wasn't enough ... There were great catch-phrases and driving pulse rhythms ... but the songs weren't serious or didn't reflect life in a realistic way. I knew that when I got into folk music, it was more of a serious type of thing. The songs are filled with more despair, more sadness, more triumph, more faith in the supernatural, much deeper feelings."[21] He soon began to perform at the 10 O'clock Scholar, a coffee house a few blocks from campus, and became actively involved in the local Dinkytown folk music circuit.[22][23]

During his Dinkytown days, Zimmerman began introducing himself as "Bob Dylan."[16] In a 2004 interview, Dylan explained: "You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free."[24] In his autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan acknowledged that he was familiar with the poetry of Dylan Thomas.[25]

1960s

Relocation to New York and record deal

Dylan dropped out of college at the end of his freshman year. In January 1961, he moved to New York City, hoping to perform there and visit his musical idol Woody Guthrie, who was seriously ill with Huntington's Disease in Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital.[26] Guthrie had been a revelation to Dylan and was the biggest influence on his early performances. Describing Guthrie's impact on him, Dylan later wrote: "The songs themselves had the infinite sweep of humanity in them ... [He] was the true voice of the American spirit. I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie's greatest disciple."[27] As well as visiting Guthrie in the hospital, Dylan befriended Guthrie's acolyte Ramblin' Jack Elliott. Much of Guthrie's repertoire was actually channeled through Elliott, and Dylan paid tribute to Elliott in Chronicles (2004).[28]

From February 1961, Dylan played at various clubs around Greenwich Village. In September, he eventually gained public recognition when Robert Shelton wrote a positive review in The New York Times of a show at Gerde's Folk City.[29] The same month Dylan played harmonica on folk singer Carolyn Hester's eponymous third album, which brought his talents to the attention of the album's producer John Hammond.[30] Hammond signed Dylan to Columbia Records in October. The performances on his first Columbia album, Bob Dylan (1962), consisted of familiar folk, blues and gospel material combined with two original compositions. The album made little impact, selling only 5,000 copies in its first year, just enough to break even.[31] Within Columbia Records, some referred to the singer as "Hammond's Folly" and suggested dropping his contract. Hammond defended Dylan vigorously, and Johnny Cash was also a powerful ally of Dylan.[31] While working for Columbia, Dylan also recorded several songs under the pseudonym Blind Boy Grunt, for Broadside Magazine, a folk music magazine and record label.[32]

Dylan made two important career moves in August 1962. He legally changed his name to Robert Dylan, and signed a management contract with Albert Grossman. Grossman remained Dylan's manager until 1970, and was notable both for his sometimes confrontational personality, and for the fiercely protective loyalty he displayed towards his principal client.[33] Dylan would subsequently describe Grossman thus: "He was kind of like a Colonel Tom Parker figure ... you could smell him coming."[23] Tensions between Grossman and John Hammond led to Hammond being replaced as the producer of Dylan's second album by the young African American jazz producer Tom Wilson.[34]

From December 1962 to January 1963, Dylan made his first trip to the UK.[35] He had been invited by TV director Philip Saville to appear in a drama, The Madhouse on Castle Street, which Saville was directing for BBC Television.[36] At the end of the play, Dylan performed Blowin' in the Wind, one of the first major public performances of the song[37] While in London, Dylan performed at several London folk clubs, including Les Cousins, The Pinder Of Wakefield,[38] and Bunjies.[35] He also learned new songs from several UK performers, including Martin Carthy.[35]

By the time Dylan's second album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, was released in May 1963, he had begun to make his name as both a singer and a songwriter. Many of the songs on this album were labeled protest songs, inspired partly by Guthrie and influenced by Pete Seeger's passion for topical songs.[39] "Oxford Town", for example, was a sardonic account of James Meredith's ordeal as the first black student to risk enrollment at the University of Mississippi.[40]

His most famous song at this time, "Blowin' in the Wind", partially derived its melody from the traditional slave song "No More Auction Block", while its lyrics questioned the social and political status quo.[41] The song was widely recorded and became an international hit for Peter, Paul and Mary, setting a precedent for many other artists who would have hits with Dylan's songs. "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" was based on the tune of the folk ballad "Lord Randall". With its veiled references to nuclear apocalypse, it gained even more resonance when the Cuban missile crisis developed only a few weeks after Dylan began performing it.[42] Like "Blowin' in the Wind", "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" marked an important new direction in modern songwriting, blending a stream-of-consciousness, imagist lyrical attack with a traditional folk form.[43] Template:Sound sample box align left

Template:Sample box end While Dylan's topical songs solidified his early reputation, Freewheelin' also included a mixture of love songs and jokey, surreal talking blues. Humor was a large part of Dylan's persona,[45] and the range of material on the album impressed many listeners, including The Beatles. George Harrison said, "We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the song lyrics and just the attitude—it was incredibly original and wonderful."[46]

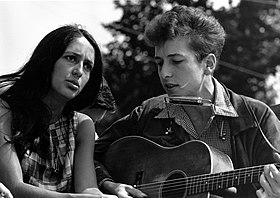

The rough edge of Dylan's singing was unsettling to some early listeners but an attraction to others. Describing the impact that Dylan had on her and her husband, Joyce Carol Oates wrote: "When we first heard this raw, very young, and seemingly untrained voice, frankly nasal, as if sandpaper could sing, the effect was dramatic and electrifying."[47] Many of his most famous early songs first reached the public through more immediately palatable versions by other performers, such as Joan Baez, who became Dylan's advocate, as well as his lover.[16] Baez was influential in bringing Dylan to national and international prominence by recording several of his early songs and inviting him onstage during her own concerts.[48]

Others who recorded and had hits with Dylan's songs in the early and mid-1960s included The Byrds, Sonny and Cher, The Hollies, Peter, Paul and Mary, Manfred Mann, and The Turtles. Most attempted to impart a pop feel and rhythm to the songs, while Dylan and Baez performed them mostly as sparse folk pieces. The cover versions became so ubiquitous that CBS started to promote him with the tag "Nobody Sings Dylan Like Dylan."[49]

"Mixed Up Confusion", recorded during the Freewheelin' sessions with a backing band, was released as a single and then quickly withdrawn. In contrast to the mostly solo acoustic performances on the album, the single showed a willingness to experiment with a rockabilly sound. Cameron Crowe described it as "a fascinating look at a folk artist with his mind wandering towards Elvis Presley and Sun Records."[50]

Protest and Another Side

In May 1963, Dylan's political profile was raised when he walked out of The Ed Sullivan Show. During rehearsals, Dylan had been informed by CBS Television's "head of program practices" that the song he was planning to perform, "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues", was potentially libelous to the John Birch Society. Rather than comply with the censorship, Dylan refused to appear on the program.[51] Template:Sound sample box align right

Template:Sample box end By this time, Dylan and Baez were both prominent in the civil rights movement, singing together at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.[52] Dylan's third album, The Times They Are a-Changin', reflected a more politicized and cynical Dylan.[53] The songs often took as their subject matter contemporary, real life stories, with "Only A Pawn In Their Game" addressing the murder of civil rights worker Medgar Evers; and the Brechtian "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" the death of black hotel barmaid Hattie Carroll, at the hands of young white socialite William Zantzinger.[54] On a more general theme, "Ballad of Hollis Brown" and "North Country Blues" address the despair engendered by the breakdown of farming and mining communities. This political material was accompanied by two personal love songs, "Boots of Spanish Leather" and "One Too Many Mornings".[55]

By the end of 1963, Dylan felt both manipulated and constrained by the folk and protest movements.[56] These tensions were publicly displayed when, accepting the "Tom Paine Award" from the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee shortly after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, an intoxicated Dylan brashly questioned the role of the committee, characterized the members as old and balding, and claimed to see something of himself (and of every man) in Kennedy's alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.[57]

Another Side of Bob Dylan, recorded on a single June evening in 1964,[16] had a lighter mood than its predecessor. The surreal, humorous Dylan reemerged on "I Shall Be Free #10" and "Motorpsycho Nightmare". "Spanish Harlem Incident" and "To Ramona" are romantic and passionate love songs, while "Black Crow Blues" and "I Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)" suggest the rock and roll soon to dominate Dylan's music. "It Ain't Me Babe", on the surface a song about spurned love, has been described as a rejection of the role his reputation had thrust at him.[58] His newest direction was signaled by two lengthy songs: the impressionistic "Chimes of Freedom", which sets elements of social commentary against a denser metaphorical landscape in a style later characterized by Allen Ginsberg as "chains of flashing images,"[59] and "My Back Pages", which attacks the simplistic and arch seriousness of his own earlier topical songs and seems to predict the backlash he was about to encounter from his former champions as he took a new direction.[60]

In the latter half of 1964 and 1965, Dylan’s appearance and musical style changed rapidly, as he made his move from leading contemporary songwriter of the folk scene to folk-rock pop-music star. His scruffy jeans and work shirts were replaced by a Carnaby Street wardrobe, sunglasses day or night, and pointy "Beatle boots". A London reporter wrote: "Hair that would set the teeth of a comb on edge. A loud shirt that would dim the neon lights of Leicester Square. He looks like an undernourished cockatoo."[61] Dylan also began to spar in increasingly surreal ways with his interviewers. Appearing on the Les Crane TV show and asked about a movie he was planning to make, he told Crane it would be a cowboy horror movie. Asked if he played the cowboy, Dylan replied, "No, I play my mother."[62]

Going electric

Dylan's March 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home was yet another stylistic leap,[63] featuring his first recordings made with electric instruments. The first single, "Subterranean Homesick Blues", owed much to Chuck Berry's "Too Much Monkey Business"[64] and was provided with an early music video courtesy of D. A. Pennebaker's cinéma vérité presentation of Dylan's 1965 tour of England, Dont Look Back.[65] Its free association lyrics both harked back to the manic energy of Beat poetry and were a forerunner of rap and hip-hop.[66]

By contrast, the B side of the album consisted of four long songs on which Dylan accompanied himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica.[67] "Mr. Tambourine Man" quickly became one of Dylan's best known songs when The Byrds recorded an electric guitar version which reached number one in both the U.S. and the U.K. charts.[68][69] "It's All Over Now Baby Blue" and "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" would be acclaimed as two of Dylan's most important compositions.[67][70]

In the summer of 1965, as the headliner at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan performed his first electric set since his high school days with a pickup group drawn mostly from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, featuring Mike Bloomfield (guitar), Sam Lay (drums) and Jerome Arnold (bass), plus Al Kooper (organ) and Barry Goldberg (piano).[71] Dylan had appeared at Newport in 1963 and 1964, but in 1965 Dylan, met with a mix of cheering and booing, left the stage after only three songs. As one version of the legend has it, the boos were from the outraged folk fans whom Dylan had alienated by appearing, unexpectedly, with an electric guitar. An alternative account claims audience members were merely upset by poor sound quality and a surprisingly short set.[72]

Dylan's 1965 Newport performance provoked an outraged response from the folk music establishment.[73] Ewan MacColl wrote in Sing Out!, "Our traditional songs and ballads are the creations of extraordinarily talented artists working inside traditions formulated over time ... But what of Bobby Dylan? ... a youth of mediocre talent. Only a non-critical audience, nourished on the watery pap of pop music could have fallen for such tenth-rate drivel."[74] On July 29, just four days after his controversial performance at Newport, Dylan was back in the studio in New York, recording "Positively 4th Street". The lyrics teemed with images of vengeance and paranoia,[75] and it was widely interpreted as Dylan's put-down of former friends from the folk community—friends he had known in the clubs along West 4th Street.[76]

Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde

Template:Sound sample box align right

In July 1965, Dylan released the single "Like a Rolling Stone", which peaked at #2 in the U.S. and at #4 in the UK charts. At over six minutes in length, the song has been widely credited with altering attitudes about what a pop single could convey. Bruce Springsteen, in his speech during Dylan's inauguration into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame said that on first hearing the single, "that snare shot sounded like somebody'd kicked open the door to your mind".[78] In 2004, Rolling Stone Magazine listed it at #1 on its list of "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[77] The song also opened Dylan's next album, Highway 61 Revisited, titled after the road that led from Dylan's Minnesota to the musical hotbed of New Orleans.[79] The songs were in the same vein as the hit single, flavored by Mike Bloomfield's blues guitar and Al Kooper's organ riffs. "Desolation Row" offers the sole acoustic exception, with Dylan making surreal allusions to a variety of figures in Western culture during this long song. Andy Gill wrote, "'Desolation Row' is an 11-minute epic of entropy which takes the form of a Fellini-esque parade of grotesques and oddities featuring a huge cast of iconic characters, some historical (Einstein, Nero), some biblical (Noah, Cain and Abel), some fictional (Ophelia, Romeo, Cinderella), some literary (T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound), and some who fit into none of the above categories, notably Dr. Filth and his dubious nurse" [80]

In support of the record, Dylan was booked for two U.S. concerts and set about assembling a band. Mike Bloomfield was unwilling to leave the Butterfield Band, so Dylan mixed Al Kooper and Harvey Brooks from his studio crew with bar-band stalwarts Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm, best known at the time for being part of Ronnie Hawkins's backing band The Hawks.[81] On August 28 at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium, the group was heckled by an audience still annoyed by Dylan's electric sound. The band's reception on September 3 at the Hollywood Bowl was more favorable.[82]

While Dylan and the Hawks met increasingly receptive audiences on tour, their studio efforts floundered. Producer Bob Johnston persuaded Dylan to record in Nashville in February 1966, and surrounded him with a cadre of top-notch session men. At Dylan's insistence, Robertson and Kooper came down from New York City to play on the sessions.[83] The Nashville sessions produced the double-album Blonde on Blonde (1966), featuring what Dylan later called "that thin wild mercury sound".[84] Al Kooper described the album as "taking two cultures and smashing them together with a huge explosion": the musical world of Nashville and the world of the "quintessential New York hipster" Bob Dylan.[85]

On November 22, 1965, Dylan secretly married 25-year-old former model Sara Lownds.[16][86] Some of Dylan’s friends (including Ramblin' Jack Elliott) claim that, in conversation immediately after the event, Dylan denied that he was married.[86] Journalist Nora Ephron first made the news public in the New York Post in February 1966 with the headline “Hush! Bob Dylan is wed.”[87]

Dylan undertook a world tour of Australia and Europe in the spring of 1966. Each show was split into two parts. Dylan performed solo during the first half, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica. In the second half, backed by the Hawks, he played high voltage electric music. This contrast provoked many fans, who jeered and slow handclapped.[88] The tour culminated in a famously raucous confrontation between Dylan and his audience at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in England.[89] (A recording of this concert, Bob Dylan Live 1966, was finally released in 1998.) At the climax of the evening, one fan, angry with Dylan's electric sound, shouted: "Judas!" to which Dylan responded, "I don't believe you ... You're a liar!". Dylan turned to his band and said "Play it fucking loud!",[90] and they launched into the final song of the night with gusto—"Like a Rolling Stone".

Motorcycle accident and reclusion

After his European tour, Dylan returned to New York, but the pressures on him continued to increase. ABC Television had paid an advance for a TV show they could screen.[91] His publisher, Macmillan, was demanding a finished manuscript of the poem/novel Tarantula. Manager Albert Grossman had already scheduled an extensive concert tour for that summer and fall.

On July 29, 1966, Dylan crashed his 500cc Triumph Tiger 100 motorcycle on a road near his home in Woodstock, New York, throwing him to the ground. Though the extent of his injuries were never fully disclosed, Dylan said that he broke several vertebrae in his neck.[92] Mystery still surrounds the circumstances of the accident[93] since no ambulance was called to the scene and Dylan was not hospitalized.[92] Dylan later expressed concern about where his career and private life were headed up until the point of the crash: "When I had that motorcycle accident ... I woke up and caught my senses, I realized that I was just workin' for all these leeches. And I didn't want to do that. Plus, I had a family and I just wanted to see my kids."[94] Many biographers believe that the crash offered Dylan the much-needed chance to escape from the pressures that had built up around him.[92][95] In the wake of his accident, Dylan withdrew from the public and, apart from a few select appearances, did not tour again for eight years.[93]

Once Dylan was well enough to resume creative work, he began editing film footage of his 1966 tour for Eat the Document, a rarely exhibited follow-up to Dont Look Back. A rough-cut was shown to ABC Television and was promptly rejected as incomprehensible to a mainstream audience.[96] In 1967 he began recording music with the Hawks at his home and in the basement of the Hawks' nearby house, called "Big Pink".[97] These songs, initially compiled as demos for other artists to record, provided hit singles for Julie Driscoll ("This Wheel's on Fire"), The Byrds ("You Ain't Goin' Nowhere", "Nothing Was Delivered"), and Manfred Mann (Quinn the Eskimo ("The Mighty Quinn"). Columbia belatedly released selections from them in 1975 as The Basement Tapes. Over the years, more and more of the songs recorded by Dylan and his band in 1967 appeared on various bootleg recordings, culminating in a five-CD bootleg set titled The Genuine Basement Tapes, containing 107 songs and alternate takes.[98] In the coming months, the Hawks recorded the album Music from Big Pink using songs they first worked on in their basement in Woodstock, and renamed themselves The Band,[99] thus beginning a long and successful recording and performing career of their own.

In October and November 1967, Dylan returned to Nashville.[100] Back in the recording studio after a 19-month break, he was accompanied only by Charlie McCoy on bass,[101] Kenny Buttrey on drums,[102] and Pete Drake on steel guitar.[103] The result was John Wesley Harding, a quiet, contemplative record of shorter songs, set in a landscape that drew on both the American West and the Bible. The sparse structure and instrumentation, coupled with lyrics that took the Judeo-Christian tradition seriously, marked a departure not only from Dylan's own work but from the escalating psychedelic fervor of the 1960s musical culture.[104] It included "All Along the Watchtower", with lyrics derived from the Book of Isaiah (21:5–9). The song was later recorded by Jimi Hendrix, whose version Dylan himself would later acknowledge as definitive.[21] Woody Guthrie died on October 3, 1967, and Dylan made his first live appearance in twenty months at a Guthrie memorial concert held at Carnegie Hall on January 20, 1968, where he was backed by The Band. Template:Sound sample box align left

Template:Sample box end Dylan's next release, Nashville Skyline (1969), was virtually a mainstream country record featuring instrumental backing by Nashville musicians, a mellow-voiced Dylan, a duet with Johnny Cash, and the hit single "Lay Lady Lay", which had been originally written for the Midnight Cowboy soundtrack, but was not submitted in time to make the final cut.[106] In May 1969, Dylan appeared on the first episode of Johnny Cash's new television show, duetting with Cash on "Girl from the North Country", "I Threw It All Away" and "Living the Blues". Dylan next travelled to England to top the bill at the Isle of Wight rock festival on August 31, 1969, after rejecting overtures to appear at the Woodstock Festival far closer to his home.[107]

1970s

In the early 1970s critics charged Dylan's output was of varied and unpredictable quality. Rolling Stone magazine writer and Dylan loyalist Greil Marcus notoriously asked "What is this shit?" upon first listening to 1970's Self Portrait.[108][109] In general, Self Portrait, a double LP including few original songs, was poorly received.[16] Later that year, Dylan released New Morning, which some considered a return to form.[110] In November 1968, Dylan had co-written "I'd Have You Anytime" with George Harrison;[111] Harrison recorded both "I'd Have You Anytime" and Dylan's "If Not For You" for his 1970 solo triple album All Things Must Pass. Dylan's surprise appearance at Harrison's 1971 Concert for Bangladesh attracted much media coverage, reflecting that Dylan's live appearances had become rare.[112]

Between March 16 and 19, 1971, Dylan reserved three days at Blue Rock Studios, a small studio in New York's Greenwich Village. These sessions resulted in one single, "Watching The River Flow", and a new recording of "When I Paint My Masterpiece".[55] On November 4, 1971 Dylan recorded "George Jackson" which he released a week later.[55] For many, the single was a surprising return to protest material, mourning the killing of Black Panther George Jackson in San Quentin Prison that summer.[113]

In 1972 Dylan signed onto Sam Peckinpah's film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, providing songs and backing music for the movie, and playing the role of "Alias", a member of Billy's gang who had some basis in history.[114] Despite the film's failure at the box office, the song "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" has proven its durability as one of Dylan's most extensively covered songs.[115][116]

Return to touring

Dylan began 1973 by signing with a new record label, David Geffen's Asylum Records, when his contract with Columbia Records expired. On his next album, Planet Waves, he used The Band as backing group, while rehearsing for a major tour. The album included two versions of "Forever Young", which became one of his most popular songs.[117] Christopher Ricks has connected the chorus of this song with John Keats's "Ode on a Grecian Urn", which contains the line "For ever panting, and for ever young."[118] As one critic described it, the song projected "something hymnal and heartfelt that spoke of the father in Dylan",[119] and Dylan himself commented: "I wrote it thinking about one of my boys and not wanting to be too sentimental."[120] Biographer Howard Sounes noted that Jakob Dylan believed the song was about him.[117]

Columbia Records simultaneously released Dylan, a haphazard collection of studio outtakes (almost exclusively cover songs), which was widely interpreted as a churlish response to Dylan's signing with a rival record label.[121] In January 1974 Dylan and The Band embarked on their high-profile, coast-to-coast North American tour. A live double album of the tour, Before the Flood, was released on Asylum Records. Template:Sound sample box align left

After the tour, Dylan and his wife became publicly estranged. He filled a small red notebook with songs about relationships and ruptures, and quickly recorded a new album entitled Blood on the Tracks in September 1974.[122] Dylan delayed the album's release, however, and re-recorded half of the songs at Sound 80 Studios in Minneapolis with production assistance from his brother David Zimmerman.[123] During this time, Dylan returned to Columbia Records which eventually reissued his Asylum albums.

Released in early 1975, Blood on the Tracks received mixed reviews. In the NME, Nick Kent described "the accompaniments [as] often so trashy they sound like mere practise takes."[124] In Rolling Stone, reviewer Jon Landau wrote that "the record has been made with typical shoddiness."[125] However, over the years critics have come to see it as one of Dylan's greatest achievements, perhaps the only serious rival to his mid-60s trilogy of albums. In Salon.com, Bill Wyman wrote: "Blood on the Tracks is his only flawless album and his best produced; the songs, each of them, are constructed in disciplined fashion. It is his kindest album and most dismayed, and seems in hindsight to have achieved a sublime balance between the logorrhea-plagued excesses of his mid-'60s output and the self-consciously simple compositions of his post-accident years."[126] Novelist Rick Moody called it "the truest, most honest account of a love affair from tip to stern ever put down on magnetic tape."[127]

That summer Dylan wrote his first successful "protest" song in 12 years, championing the cause of boxer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, who had been imprisoned for a triple murder in Paterson, New Jersey. After visiting Carter in jail, Dylan wrote "Hurricane", presenting the case for Carter's innocence. Despite its 8:32 minute length, the song was released as a single, peaking at #33 on the U.S. Billboard Chart, and performed at every 1975 date of Dylan's next tour, the Rolling Thunder Revue.[128] The tour was a varied evening of entertainment featuring about one hundred performers and supporters[129] drawn from the resurgent Greenwich Village folk scene, including T-Bone Burnett, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Joni Mitchell.[130] David Mansfield, Roger McGuinn, Mick Ronson, Joan Baez, and violinist Scarlet Rivera, whom Dylan discovered while she was walking down the street, her violin case hanging on her back.[131] Allen Ginsberg accompanied the troupe, staging scenes for the film Dylan was simultaneously shooting. Sam Shepard was initially hired to write the film's screenplay, but ended up accompanying the tour as informal chronicler.[132]

Running through late 1975 and again through early 1976, the tour encompassed the release of the album Desire, with many of Dylan's new songs featuring an almost travelogue-like narrative style, showing the influence of his new collaborator, playwright Jacques Levy.[133][134] The spring 1976 half of the tour was documented by a TV concert special, Hard Rain, and the LP Hard Rain; no concert album from the better-received and better-known opening half of the tour was released until 2002's Live 1975.[135]

The fall 1975 tour with the Revue also provided the backdrop to Dylan's nearly four-hour film Renaldo and Clara, a sprawling and improvised narrative, mixed with concert footage and reminiscences. Released in 1978, the movie received generally poor, sometimes scathing, reviews and had a very brief theatrical run.[136][137] Later in that year, Dylan allowed a two-hour edit, dominated by the concert performances, to be more widely released.[138]

In November 1976 Dylan appeared at The Band's "farewell" concert, along with other guests including Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison and Neil Young. Martin Scorsese's acclaimed cinematic chronicle of this show, The Last Waltz, was released in 1978 and included about half of Dylan's set.[139] In 1976, Dylan also wrote and duetted on the song "Sign Language" for Eric Clapton's No Reason To Cry[140].

Dylan's 1978 album Street-Legal, recorded with a large, pop-rock band, complete with female backing vocalists, was lyrically one of his more complex and cohesive.[141] It suffered, however, from a poor sound mix (attributed to his studio recording practices),[142] submerging much of its instrumentation until its remastered CD release nearly a quarter century later.

Born-again period

Template:Sound sample box align left

Template:Sample box end In the late 1970s, Dylan became a born-again Christian[143][144][145] and released two albums of Christian gospel music. Slow Train Coming (1979) featured the guitar accompaniment of Mark Knopfler (of Dire Straits) and was produced by veteran R&B producer, Jerry Wexler. Wexler recalled that when Dylan had tried to evangelize him during the recording, he replied: "Bob, you're dealing with a sixty-two-year old Jewish atheist. Let's just make an album."[146] The album won Dylan a Grammy Award as "Best Male Vocalist" for the song "Gotta Serve Somebody". The second evangelical album, Saved (1980), received mixed reviews, although Kurt Loder in Rolling Stone declared the album was far superior, musically, to its predecessor.[147] When touring from the fall of 1979 through the spring of 1980, Dylan would not play any of his older, secular works, and he delivered declarations of his faith from the stage, such as:

Years ago they ... said I was a prophet. I used to say, "No I'm not a prophet" they say "Yes you are, you're a prophet." I said, "No it's not me." They used to say "You sure are a prophet." They used to convince me I was a prophet. Now I come out and say Jesus Christ is the answer. They say, "Bob Dylan's no prophet." They just can't handle it.[148]

Dylan's embrace of Christianity was unpopular with some of his fans and fellow musicians.[149] Shortly before his murder, John Lennon recorded "Serve Yourself" in response to Dylan's "Gotta Serve Somebody".[150] By 1981, while Dylan's Christian faith was obvious, Stephen Holden wrote in the New York Times that "neither age (he's now 40) nor his much-publicized conversion to born-again Christianity has altered his essentially iconoclastic temperament."[151]

1980s

Photo: F. Antolín Hernandez

In the fall of 1980 Dylan briefly resumed touring for a series of concerts billed as "A Musical Retrospective", where he restored several of his popular 1960s songs to the repertoire. Shot of Love, recorded the next spring, featured Dylan's first secular compositions in more than two years, mixed with explicitly Christian songs. The haunting "Every Grain of Sand" reminded some critics of William Blake’s verses.[152]

In the 1980s the quality of Dylan's recorded work varied, from the well-regarded Infidels in 1983 to the panned Down in the Groove in 1988. Critics such as Michael Gray condemned Dylan's 1980s albums both for showing an extraordinary carelessness in the studio and for failing to release his best songs.[153] The Infidels recording sessions, for example, produced several notable songs that Dylan left off the album. Most well regarded of these were "Blind Willie McTell" (a tribute to the dead blues singer and an evocation of African American history[154]), "Foot of Pride" and "Lord Protect My Child".[155] These songs were later released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991.

Between July 1984 and March 1985, Dylan recorded his next studio album, Empire Burlesque.[156] Arthur Baker, who had remixed hits for Bruce Springsteen and Cyndi Lauper, was asked to engineer and mix the album. Baker has said he felt he was hired to make Dylan's album sound "a little bit more contemporary".[156]

Dylan sang on USA for Africa's famine relief fundraising single "We Are the World". On July 13, 1985, he appeared at the climax at the Live Aid concert at JFK Stadium, Philadelphia. Backed by Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood, Dylan performed a ragged version of "Hollis Brown", his ballad of rural poverty, and then said to the worldwide audience exceeding one billion people: "I hope that some of the money ... maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe ... one or two million, maybe ... and use it to pay the mortgages on some of the farms and, the farmers here, owe to the banks."[157] His remarks were widely criticized as inappropriate, but they did inspire Willie Nelson to organize a series of events, Farm Aid, to benefit debt-ridden American farmers.[158]

In April 1986, Dylan made a foray into the world of rap music when he added vocals to a verse of Kurtis Blow's "Street Rock", which appeared on Blow's album Kingdom Blow. Credited with making arrangements for Dylan's performance are veteran singer-songwriter-producer, Wayne K. Garfield, who conceived the collaboration and former Dylan back-up singer, Debra Byrd, who is now head vocal coach for American Idol.[159] In July 1986 Dylan released Knocked Out Loaded, an album containing three cover songs (by Little Junior Parker, Kris Kristofferson and the traditional gospel hymn "Precious Memories"), three collaborations with other writers (Tom Petty, Sam Shepard and Carole Bayer Sager), and two solo compositions by Dylan. The album received mainly negative reviews; Rolling Stone called it "a depressing affair",[160] and it was the first Dylan album since Freewheelin' (1963) to fail to make the Top 50.[161] Since then, some critics have called the 11-minute epic that Dylan co-wrote with Sam Shepard, 'Brownsville Girl', a work of genius.[162] In 1986 and 1987, Dylan toured extensively with Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers, sharing vocals with Petty on several songs each night. Dylan also toured with The Grateful Dead in 1987, resulting in a live album Dylan & The Dead. This album received some very negative reviews: Allmusic said, "Quite possibly the worst album by either Bob Dylan or the Grateful Dead."[163] After performing with these musical permutations, Dylan initiated what came to be called The Never Ending Tour on June 7, 1988, performing with a tight back-up band featuring guitarist G. E. Smith. Dylan would continue to tour with this small but constantly evolving band for the next 20 years.[55]

Photo: Jean-Luc Ourlin

In 1987, Dylan starred in Richard Marquand's movie Hearts of Fire, in which he played Billy Parker, a washed-up-rock-star-turned-chicken farmer whose teenage lover (Fiona) leaves him for a jaded English synth-pop sensation (played by Rupert Everett).[164] Dylan also contributed two original songs to the soundtrack—"Night After Night", and "I Had a Dream About You, Baby", as well as a cover of John Hiatt's "The Usual". The film was a critical and commercial flop.[165] Dylan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in January 1988. Bruce Springsteen's induction speech declared: "Bob freed your mind the way Elvis freed your body. He showed us that just because music was innately physical did not mean that it was anti-intellectual."[166] Dylan then released the album Down in the Groove, which was even more unsuccessful in its sales than his previous studio album.[167] The song "Silvio", however, had some success as a single.[168] Later that spring, Dylan was a co-founder and member of the Traveling Wilburys with George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, and Tom Petty returning to the album charts with the multi-platinum selling Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1.[167] Despite Orbison's death in December 1988, the remaining four recorded a second album in May 1990, which they released with the unexpected title Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3.[169]

Dylan finished the decade on a critical high note with Oh Mercy produced by Daniel Lanois. Rolling Stone magazine called the album "both challenging and satisfying".[170][171] The track "Most of the Time", a lost love composition, was later prominently featured in the film High Fidelity, while "What Was It You Wanted?" has been interpreted both as a catechism and a wry comment on the expectations of critics and fans.[172] The religious imagery of "Ring Them Bells" struck some critics as a re-affirmation of faith.[173]

1990s

Dylan's 1990s began with Under the Red Sky (1990), an about-face from the serious Oh Mercy. The album contained several apparently simple songs, including "Under the Red Sky" and "Wiggle Wiggle". The album was dedicated to "Gabby Goo Goo"; this was later explained as a nickname for the daughter of Dylan and Carolyn Dennis, Desiree Gabrielle Dennis-Dylan, who was four at that time.[174] Sidemen on the album included George Harrison, Slash from Guns N' Roses, David Crosby, Bruce Hornsby, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Elton John. Despite the stellar line-up, the record received bad reviews and sold poorly. Dylan did not make another studio album of new songs for seven years.[175]

In 1991, Dylan was honored by the recording industry with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.[176] The event coincided with the start of the Gulf War against Saddam Hussein, and Dylan performed his song "Masters of War".[177] Dylan then made a short speech which startled some of the audience.[177]

The next few years saw Dylan returning to his roots with two albums covering old folk and blues numbers: Good as I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993), featuring interpretations and acoustic guitar work. Many critics and fans commented on the quiet beauty of the song "Lone Pilgrim",[178] penned by a 19th century teacher and sung by Dylan with a haunting reverence. An exception to this rootsy mood came in Dylan's 1991 songwriting collaboration with Michael Bolton; the resulting song "Steel Bars", was released on Bolton's album Time, Love & Tenderness. In November 1994 Dylan recorded two live shows for MTV Unplugged. He claimed his wish to perform a set of traditional songs for the show was overruled by Sony executives who insisted on a greatest hits package.[179] The album produced from it, MTV Unplugged, included "John Brown", an unreleased 1963 song detailing the ravages of both war and jingoism.

With a collection of songs reportedly written while snowed-in on his Minnesota ranch,[180] Dylan booked recording time with Daniel Lanois at Miami's Criteria Studios in January 1997. The subsequent recording sessions were, by some accounts, fraught with musical tension.[181] Late that spring, before the album's release, Dylan was hospitalized with a life-threatening heart infection, pericarditis, brought on by histoplasmosis. His scheduled European tour was cancelled, but Dylan made a speedy recovery and left the hospital saying, "I really thought I'd be seeing Elvis soon."[182] He was back on the road by midsummer, and in early fall performed before Pope John Paul II at the World Eucharistic Conference in Bologna, Italy. The Pope treated the audience of 200,000 people to a sermon based on Dylan's lyric "Blowin' in the Wind".[183]

September saw the release of the new Lanois-produced album, Time Out of Mind. With its bitter assessment of love and morbid ruminations, Dylan's first collection of original songs in seven years was highly acclaimed. Rolling Stone said "Mortality bears down hard, while shots of gallows humor ring out."[184] This collection of complex songs won him his first solo "Album of the Year" Grammy Award (he was one of numerous performers on The Concert for Bangladesh, the 1972 winner). The love song "Make You Feel My Love" became a number one country hit for Garth Brooks.[16]

In December 1997 U.S. President Bill Clinton presented Dylan with a Kennedy Center Honor in the East Room of the White House, paying this tribute: "He probably had more impact on people of my generation than any other creative artist. His voice and lyrics haven't always been easy on the ear, but throughout his career Bob Dylan has never aimed to please. He's disturbed the peace and discomforted the powerful."[185]

2000s

Template:Sound sample box align left

Template:Sample box end Dylan commenced the new millennium by winning his first Oscar; his song "Things Have Changed", penned for the film Wonder Boys, won a Golden Globe and an Academy Award in March 2001.[187] The Oscar (by some reports a facsimile) tours with him, presiding over shows perched atop an amplifier.[188]

"Love and Theft" was released on September 11, 2001. Recorded with his touring band, Dylan produced the album himself under the pseudonym Jack Frost.[189] The album was critically well-received and earned nominations for several Grammy awards.[190] Critics noted that Dylan was widening his musical palette to include rockabilly, Western swing, jazz, and even lounge ballads.[191]

In 2003 Dylan revisited the evangelical songs from his "born again" period and participated in the CD project Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs of Bob Dylan. That year also saw the release of the film Masked & Anonymous, a collaboration with TV producer Larry Charles that had Dylan appearing in a cast of well-knowns, including Jeff Bridges, Penelope Cruz and John Goodman. The film polarised critics: many dismissed it as an “incoherent mess”[192][193]; a few treated it as a serious work of art.[194][195]

In October 2004, Dylan published the first part of his autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One. The book confounded expectations.[196] Dylan devoted three chapters to his first year in New York City in 1961–1962, virtually ignoring the mid-'60s when his fame was at its height. He also devoted chapters to the albums New Morning (1970) and Oh Mercy (1989). The book reached number two on The New York Times' Hardcover Non-Fiction best seller list in December 2004 and was nominated for a National Book Award.[197]

Martin Scorsese's acclaimed[198] film biography No Direction Home was broadcast in September 2005.[199] The documentary focuses on the period from Dylan's arrival in New York in 1961 to his motorcycle crash in 1966, featuring interviews with Suze Rotolo, Liam Clancy, Joan Baez, Allen Ginsberg, Pete Seeger, Mavis Staples, and Dylan himself. The film received a Peabody Award in April 2006[200] and a Columbia-duPont Award in January 2007.[201] The accompanying soundtrack featured unreleased songs from Dylan's early career.

Modern Times (2006–08)

May 3, 2006, was the premiere of Dylan's DJ career, hosting a weekly radio program, Theme Time Radio Hour, for XM Satellite Radio, with song selections revolving around a chosen theme.[202][203] Dylan played classic and obscure records from the 1930s to the present day, including contemporary artists as diverse as Blur, Prince, L.L. Cool J and The Streets. The show was praised by fans and critics as "great radio," as Dylan told stories and made eclectic references with his sardonic humor, while achieving a thematic beauty with his musical choices.[204][205] Music author Peter Guralnick commented: "With this show, Dylan is tapping into his deep love—and I would say his belief in—a musical world without borders. I feel like the commentary often reflects the same surrealistic appreciation for the human comedy that suffuses his music."[206] In April 2009, Dylan broadcast the 100th show in his radio series; the theme was "Goodbye" and the final record played was Woody Guthrie's "So Long, It's Been Good To Know Yuh". This has led to speculation that Dylan's radio series may have ended.[207]

On August 29, 2006, Dylan released his Modern Times album. In a Rolling Stone interview, Dylan criticized the quality of modern sound recordings and claimed that his new songs "probably sounded ten times better in the studio when we recorded 'em."[208] Despite some coarsening of Dylan’s voice (a critic for The Guardian characterised his singing on the album as "a catarrhal death rattle"[209]) most reviewers praised the album, and many described it as the final installment of a successful trilogy, embracing Time Out of Mind and "Love and Theft".[210] Modern Times entered the U.S. charts at number one, making it Dylan's first album to reach that position since 1976's Desire.[211]

Nominated for three Grammy Awards, Modern Times won Best Contemporary Folk/Americana Album and Bob Dylan also won Best Solo Rock Vocal Performance for "Someday Baby". Modern Times was named Album of the Year, 2006, by Rolling Stone magazine,[212] and by Uncut in the UK.[213] On the same day that Modern Times was released the iTunes Music Store released Bob Dylan: The Collection, a digital box set containing all of his albums (773 tracks in total), along with 42 rare and unreleased tracks.[214]

August 2007 saw the unveiling of the award-winning film I'm Not There,[215][216] written and directed by Todd Haynes, bearing the tagline "inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan".[217] The movie uses six distinct characters to represent different aspects of Dylan's life, played by Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, Marcus Carl Franklin, Richard Gere, Heath Ledger and Ben Whishaw.[217][218] Dylan's previously unreleased 1967 recording from which the film takes its name[219] was released for the first time on the film's original soundtrack; all other tracks are covers of Dylan songs, specially recorded for the movie by a diverse range of artists, including Eddie Vedder, Stephen Malkmus, Jeff Tweedy, Willie Nelson, Cat Power, Richie Havens, and Tom Verlaine.[220]

On October 1, 2007, Columbia Records released the triple CD retrospective album Dylan, anthologising his entire career under the Dylan 07 logo.[221] As part of this campaign, Mark Ronson produced a re-mix of Dylan's 1966 tune "Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I'll Go Mine)", which was released as a maxi-single. This was the first time Dylan had sanctioned a re-mix of one of his classic recordings.[222]

The sophistication of the Dylan 07 marketing campaign was a reminder that Dylan’s commercial profile had risen considerably since the 1990s. This first became evidenced in 2004, when Dylan appeared in a TV advertisement for Victoria’s Secret lingerie[223]. Three years later, in October 2007, he participated in a multi-media campaign for the 2008 Cadillac Escalade.[224][225] Then, in 2009, he gave the highest profile endorsement of his career, appearing with rapper Will.i.am in a Pepsi ad that debuted during the telecast of Super Bowl XLIII.[226] The ad, broadcast to a record audience of 98 million viewers, opened with Dylan singing the first verse of "Forever Young" followed by Will.i.am doing a hip hop version of the song's third and final verse.[227][228][229]

Over a decade after Random House had published Drawn Blank (1994), a book of Dylan's drawings, an exhibit of his art, The Drawn Blank Series, opened in October 2007 at the Kunstsammlungen in Chemnitz, Germany.[230] This first public exhibition of Dylan's paintings showcased more than 200 watercolors and gouaches made earlier in 2007 from the original drawings. The exhibition's opening also premiered the release of the book Bob Dylan: The Drawn Blank Series, which includes 170 reproductions from the series.[230][231][232]

In October 2008, Columbia released Volume 8 of Dylan's Bootleg Series, Tell Tale Signs: Rare And Unreleased 1989-2006 as both a two-CD set and a three-CD version with a 150-page hardcover book. The set contains live performances and outtakes from selected studio albums from Oh Mercy to Modern Times, as well as soundtrack contributions and collaborations with David Bromberg and Ralph Stanley.[233] The pricing of the album—the two-CD set went on sale for $18.99 and the three-CD version for $129.99—led to complaints about "rip-off packaging" from some fans and commentators.[234][235] The release was widely acclaimed by critics.[236] The plethora of alternative takes and unreleased material suggested to Uncut's reviewer: "Tell Tale Signs is awash with evidence of (Dylan's) staggering mercuriality, his evident determination even in the studio to repeat himself as little as possible."[237]

Together Through Life and Christmas In The Heart (2009)

Bob Dylan released his album Together Through Life on April 28, 2009.[238][239] In a conversation with music journalist Bill Flanagan, published on Dylan's website, Dylan explained that the genesis of the record was when French film director Olivier Dahan asked him to supply a song for his new road movie, My Own Love Song; initially only intending to record a single track, "Life Is Hard," "the record sort of took its own direction". Nine of the ten songs on the album are credited as co-written by Bob Dylan and Robert Hunter.[240]

The album received largely favourable reviews,[241] although several critics described it as a minor addition to Dylan's canon of work. In Rolling Stone magazine, David Fricke wrote: "The album may lack the instant-classic aura of Love and Theft or Modern Times, but it is rich in striking moments, set in a willful rawness."[242] Dylan critic Andy Gill wrote in The Independent that the record "features Dylan in fairly relaxed, spontaneous mood, content to grab such grooves and sentiments as flit momentarily across his radar. So while it may not contain too many landmark tracks, it's one of the most naturally enjoyable albums you'll hear all year."[243]

In its first week of release, the album reached number one in the Billboard 200 chart in the U.S.,[244] making Bob Dylan (68 years of age) the oldest artist to ever debut at number one in the Billboard 200 chart.[244] It also reached number one on the UK album charts, 39 years after Dylan's previous UK album chart topper New Morning. This meant that Dylan currently holds the record for the longest gap between solo number one albums in the UK chart.[245]

On October 13, 2009, Dylan released a Christmas album, Christmas in the Heart, comprising such Christmas standards as "Little Drummer Boy", "Winter Wonderland" and "Here Comes Santa Claus".[246] The U.S. royalties from the collection will benefit Feeding America, which has been described as the nation's leading hunger-relief charity.[247]

The album received generally favourable reviews.[248]The New Yorker commented that Dylan had welded a pre-rock musical sound to "some of his croakiest vocals in a while", and speculated that Dylan's intentions might be ironic: "Dylan has a long and highly publicized history with Christianity; to claim there’s not a wink in the childish optimism of “Here Comes Santa Claus” or “Winter Wonderland” is to ignore a half-century of biting satire."[249] In USA Today, Edna Gundersen pointed out that Dylan was "revisiting yuletide styles popularized by Nat King Cole, Mel Tormé, and the Ray Conniff Singers." Gundersen concluded that Dylan "couldn't sound more sentimental or sincere".[250]

In an interview published by Street News Service, journalist Bill Flanagan asked Dylan why he had performed the songs in a straightforward style, and Dylan responded: "There wasn’t any other way to play it. These songs are part of my life, just like folk songs. You have to play them straight too."[251]

Never Ending Tour

The Never Ending Tour commenced on June 7, 1988,[252] and Dylan has played roughly 100 dates a year for the entirety of the 1990s and the 2000s—a heavier schedule than most performers who started out in the 1960s.[253] By the end of 2008, Dylan and his band had played more than 2100 shows,[254] anchored by long-time bassist Tony Garnier and filled out with talented sidemen. To the dismay of some of his audience,[255] Dylan's performances remain unpredictable as he alters his arrangements and changes his vocal approach night after night.[256] Critical opinion about Dylan’s shows remains divided. Critics such as Richard Williams and Andy Gill have argued that Dylan has found a successful way to present his rich legacy of material.[257][258] Others have criticised his vocal style as a “one-dimensional growl with which he chews up, mangles and spits out the greatest lyrics ever written so that they are effectively unrecognisable”,[259] and his lack of interest in bonding with his audience.[260]

Bob Dylan's European tour of spring 2009 opened in Stockholm on March 22 and ended in Dublin on May 6.[261] Dylan recently finished touring the United States, concluding in New York in November.[262]

Personal life

Family

Dylan married Sara Lownds on November 22, 1965. Their first child, Jesse Byron Dylan, was born on January 6, 1966, and they had three more children: Anna Lea, Samuel Isaac Abraham, and Jakob Luke (born December 9, 1969). Dylan also adopted Sara's daughter from a prior marriage, Maria Lownds (later Dylan), (born October 21, 1961 now married to musician Peter Himmelman). In the 1990s his son Jakob Dylan became well known as the lead singer of the band The Wallflowers. Jesse Dylan is a film director and a successful businessman. Bob and Sara Dylan were divorced on June 29, 1977.[263]

In June 1986, Dylan married his longtime backup singer Carolyn Dennis (often professionally known as Carol Dennis).[264] Their daughter, Desiree Gabrielle Dennis-Dylan, was born on January 31, 1986. The couple divorced in October 1992. Their marriage and child remained a closely guarded secret until the publication of Howard Sounes' Dylan biography, Down the Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan in 2001.[265]

Religious beliefs

Growing up in Hibbing, Dylan and his parents were part of the area's small but close-knit Jewish community, and in May 1954 Dylan had his Bar Mitzvah.[266] However, for a period during the late 1970s and early 80s, Bob Dylan publicly converted to Christianity. From January to April 1979, Dylan participated in Bible study classes at the Vineyard School of Discipleship in Reseda, California. Pastor Kenn Gulliksen has recalled: "Larry Myers and Paul Emond went over to Bob’s house and ministered to him. He responded by saying, 'Yes he did in fact want Christ in his life.' And he prayed that day and received the Lord."[267][268]

By 1984, Dylan was deliberately distancing himself from the "born-again" label. He told Kurt Loder of Rolling Stone magazine: "I've never said I'm born again. That's just a media term. I don't think I've been an agnostic. I've always thought there's a superior power, that this is not the real world and that there's a world to come."[269]

Since his trilogy of Christian albums, Dylan's faith has been a subject of scrutiny. In 1997 he told David Gates of Newsweek:

Here's the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don't find it anywhere else. Songs like "Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain" or "I Saw the Light"—that's my religion. I don't adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I've learned more from the songs than I've learned from any of this kind of entity. The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs.[2]

In an interview published in The New York Times on September 28, 1997, journalist Jon Pareles reported that "Dylan says he now subscribes to no organized religion."[270]

Dylan has been described, in the last 20 years, as a supporter of the Chabad Lubavitch movement[271] and has privately participated in Jewish religious events, including the bar mitzvahs of his sons. Subsequently, Jewish news services have reported that Dylan has "shown up" a few times at various High Holiday services at various Chabad synagogues.[272] For example, he attended Congregation Beth Tefillah, in Atlanta, Georgia on September 22, 2007 (Yom Kippur), where he was called to the Torah for the sixth aliyah.[273]

Dylan has continued to perform songs from his gospel albums in concert, occasionally covering traditional religious songs. He has also made passing references to his religious faith—such as in a 2004 interview with 60 Minutes, when he told Ed Bradley that "the only person you have to think twice about lying to is either yourself or to God." He also explained his constant touring schedule as part of a bargain he made a long time ago with the "chief commander—in this earth and in the world we can't see."[24]

In October 2009, Dylan released Christmas in the Heart, an album of Christmas songs which included the traditional carols "O Come All Ye Faithful" and "O Little Town of Bethlehem".[274]

Legacy

Bob Dylan has been described as one of the most influential figures of the 20th century, musically and culturally. Dylan was included in the Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century where he was called "master poet, caustic social critic and intrepid, guiding spirit of the counterculture generation".[275] In 2004, he was ranked number two in Rolling Stone magazine's list of "Greatest Artists of All Time".[276] Dylan biographer Howard Sounes placed him in even more exalted company when he said, "There are giant figures in art who are sublimely good—Mozart, Picasso, Frank Lloyd Wright, Shakespeare, Dickens. Dylan ranks alongside these artists."[277]

Initially modelling his style on the songs of Woody Guthrie,[278] and lessons learnt from the blues of Robert Johnson,[279] Dylan added increasingly sophisticated lyrical techniques to the folk music of the early 60s, infusing it "with the intellectualism of classic literature and poetry".[280] Paul Simon suggested that Dylan's early compositions virtually took over the folk genre: "[Dylan's] early songs were very rich ... with strong melodies. 'Blowin' in the Wind' has a really strong melody. He so enlarged himself through the folk background that he incorporated it for a while. He defined the genre for a while."[281]

When Dylan made his move from acoustic music to a rock backing, the mix became more complex. For many critics, Dylan's greatest achievement was the cultural synthesis exemplified by his mid-'60s trilogy of albums—Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. In Mike Marqusee's words: "Between late 1964 and the summer of 1966, Dylan created a body of work that remains unique. Drawing on folk, blues, country, R&B, rock'n'roll, gospel, British beat, symbolist, modernist and Beat poetry, surrealism and Dada, advertising jargon and social commentary, Fellini and Mad magazine, he forged a coherent and original artistic voice and vision. The beauty of these albums retains the power to shock and console."[282]

One legacy of Dylan’s verbal sophistication was the increasing attention paid by literary critics to his lyrics. Professor Christopher Ricks published a 500 page analysis of Dylan’s work, placing him in the context of Eliot, Keats and Tennyson,[283] and claiming that Dylan was a poet worthy of the same close and painstaking analysis.[284] Former British poet laureate, Andrew Motion, argued that Bob Dylan’s lyrics should be studied in schools.[285] Since 1996, academics have lobbied the Swedish Academy to award Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature.[286][287][288][289]

Dylan’s voice was, in some ways, as startling as his lyrics. New York Times critic Robert Shelton described Dylan's early vocal style as "a rusty voice suggesting Guthrie's old performances, etched in gravel like Dave Van Ronk's."[290] When the young Bobby Womack told Sam Cooke he didn’t understand Dylan’s vocal style, Cooke explained that: “from now on, it's not going to be about how pretty the voice is. It's going to be about believing that the voice is telling the truth.”[291] Rolling Stone magazine ranked Dylan at number seven in their 2008 listing of “The 100 Greatest Singers of All Time”.[292] Bono commented that “Dylan has tried out so many personas in his singing because it is the way he inhabits his subject matter.”[291]

Dylan's influence has been felt in several musical genres. As Edna Gundersen stated in USA Today: "Dylan's musical DNA has informed nearly every simple twist of pop since 1962."[293] Many musicians have testified to Dylan's influence, such as Joe Strummer, who praised Dylan as having "laid down the template for lyric, tune, seriousness, spirituality, depth of rock music."[294] Other major musicians to have acknowledged Dylan's importance include John Lennon,[295] Paul McCartney,[296] Neil Young,[297][298] Bruce Springsteen,[299] David Bowie,[300] Bryan Ferry,[301] Syd Barrett,[302] Nick Cave,[303][304] Patti Smith,[305] Joni Mitchell,[306] Cat Stevens[307], and Tom Waits.[308]

There have been dissenters. Because Dylan was widely credited with imbuing pop culture with a new seriousness, the critic Nik Cohn objected: "I can't take the vision of Dylan as seer, as teenage messiah, as everything else he's been worshipped as. The way I see him, he's a minor talent with a major gift for self-hype."[309] Similarly, Australian critic Jack Marx credited Dylan with changing the persona of the rock star: "What cannot be disputed is that Dylan invented the arrogant, faux-cerebral posturing that has been the dominant style in rock since, with everyone from Mick Jagger to Eminem educating themselves from the Dylan handbook."[310]

If Dylan’s legacy in the 1960s was seen as bringing intellectual ambition to popular music, as Dylan advances into his sixties, he is today described as a figure who has greatly expanded the folk culture from which he initially emerged. As J. Hoberman wrote in The Village Voice, "Elvis might never have been born, but someone else would surely have brought the world rock 'n' roll. No such logic accounts for Bob Dylan. No iron law of history demanded that a would-be Elvis from Hibbing, Minnesota, would swerve through the Greenwich Village folk revival to become the world's first and greatest rock 'n' roll beatnik bard and then—having achieved fame and adoration beyond reckoning—vanish into a folk tradition of his own making."[311]

Discography

Awards

Notes

- ^ a b An interview with Bobby Vee suggests the young Zimmerman may have been eccentric in spelling his early pseudonym: "[Dylan] was in the Fargo/Moorhead area ... Bill [Velline] was in a record shop in Fargo, Sam's Record Land, and this guy came up to him and introduced himself as Elston Gunnn--with three n's, G-U-N-N-N." Bobby Vee Interview, July 1999, Goldmine Reproduced online:"Early alias for Robert Zimmerman". Expecting Rain. 1999-08-11. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ a b c Gates, David (1997-10-06). "Dylan Revisited". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Dylan sang Blowin’ In The Wind at the Washington D.C. concert, January 20, 1986, which marked the inauguration of Martin Luther King Day. Gray, 2006, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, pp. 63–64.

- ^ "Dylan 'reveals origin of anthem'". BBC News. 2004-04-11. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ Browne, David (2001-09-10). "Love and Theft review". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Dylan Way Opens in Duluth". Northlands News Centre. 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ "The Pulitzer Prize Winners 2008: Special Citation". Pulitzer. 2008-05-07. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ "Bob Dylan's Holiday LP Christmas in the Heart Due October 13th". bobdylan.com. 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p. 14, gives his Hebrew name as Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham

- ^ A Chabad news service gives the variant Zushe ben Avraham, which may be a Yiddish variant "Singer/Songwriter Bob Dylan Joins Yom Kippur Services in Atlanta". Chabad.org News. 2007-09-24. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Williams, Stacey. "Bob Dylan -His Life and Times-". bobdylan.com. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

Bob Dylan was born in Duluth, Minnesota, on May 24, 1941.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p. 14

- ^ a b Sounes, Down the Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c d e f g Updated from The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (Simon & Schuster, 2001). "Bob Dylan: Biography". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, pp. 29–37.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 39–43.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d e Biograph, 1985, Liner notes & text by Cameron Crowe.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 65–82.

- ^ a b This is related in the documentary film No Direction Home, Director: Martin Scorsese. Broadcast: September 26, 2005, PBS & BBC Two

- ^ a b Leung, Rebecca (2005-06-12). " "Dylan Looks Back". CBS News. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One, p. 98.

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One, pp. 244–246.

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One, pp. 250–252.

- ^ Robert Shelton, New York Times, 1961-09-21, "Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Stylist" reproduced online: Robert Shelton (1961-09-21). "Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Stylist". Bob Dylan Roots. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Richie Unterberger (2003-10-08). "Carolyn Hester Biography". All Music. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ a b Scaduto, Bob Dylan, p. 110.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b c Heylin, 1996, Bob Dylan: A Life In Stolen Moments, pp. 35–39.

- ^ "Dylan in the Madhouse". BBC TV. 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ^ Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan. Doubleday 2001. p159. ISBN 0-552-99929-6

- ^ Web Guardian newspaper © Guardian News and Media Limited 2009

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 138–142.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, p. 156.

- ^ The booklet by John Bauldie accompanying Dylan's The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991 (1991) says: "Dylan acknowledged the debt in 1978 to journalist Marc Rowland: Blowin' In The Wind' has always been a spiritual. I took it off a song called 'No More Auction Block'—that's a spiritual and 'Blowin' In The Wind follows the same feeling.'" pp. 6–8.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Ricks, Dylan's Visions of Sin, pp. 329–344.

- ^ Gill, My Back Pages, 23

- ^ Scaduto, Bob Dylan, p. 35.

- ^ Mojo magazine, December 1993.

- ^ Hedin (ed.), 2004, Studio A: The Bob Dylan Reader, p. 259. Reproduced online:Joyce Carol Oates (2001-05-24). "Dylan at 60". University of San Francisco. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Joan Baez entry, Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, pp. 28–31.

- ^ Meacham, Steve (2007-08-15). "It ain't me babe but I like how it sounds". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Biograph, 1985, Liner notes & text by Cameron Crowe. Musicians on "Mixed Up Confusion": George Barnes & Bruce Langhorne (guitars); Dick Wellstood (piano); Gene Ramey (bass); Herb Lovelle (drums)

- ^ Dylan had recorded "Talkin' John Birch Society Blues" for his Freewheelin album, but the song was replaced by later compositions, including "Masters of War". See Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Dylan performed "Only a Pawn in Their Game" and "When the Ship Comes In"; see Heylin, Bob Dylan: A Life In Stolen Moments, p. 49.

- ^ Gill, My Back Pages, pp. 37–41.

- ^ Ricks, Dylan's Visions of Sin, pp. 221–233.

- ^ a b c d "Bob Dylan Timeline". BBC. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 200–205.

- ^ Part of Dylan's speech went: "There's no black and white, left and right to me any more; there's only up and down and down is very close to the ground. And I'm trying to go up without thinking of anything trivial such as politics."; see, Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 200–205.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, p. 222.

- ^ In an interview with Seth Goddard for Life magazine (July 5, 2001) Ginsberg claimed that Dylan’s technique had been inspired by Jack Kerouac: "(Dylan) pulled Mexico City Blues from my hand and started reading it and I said, 'What do you know about that?' He said, 'Somebody handed it to me in '59 in St. Paul and it blew my mind.' So I said 'Why?' He said, 'It was the first poetry that spoke to me in my own language.' So those chains of flashing images you get in Dylan, like 'the motorcycle black Madonna two-wheeled gypsy queen and her silver studded phantom lover,' they're influenced by Kerouac's chains of flashing images and spontaneous writing, and that spreads out into the people." Reproduced online at: "Online Interviews With Allen Ginsberg". University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. 2004-10-08. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 219–222.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 267–271; pp. 288–291.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 178–181.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Heylin, 2009, Revolution In The Air, The Songs of Bob Dylan: Volume One, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Gill, My Back Pages, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Marqusee, Wicked Messenger, p. 144.

- ^ a b Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Warwick, N., Brown, T. & Kutner, J. (2004). The Complete Book of the British Charts (Third Edition ed.). Omnibus Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781844490585.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Byrds chart data". Ultimate Music Database. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ Shelton, 2003, No Direction Home, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 208–216.

- ^ "Exclusive: Dylan at Newport—Who Booed?". Mojo. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, pp. 305–314.

- ^ Sing Out, September 1965, quoted in Shelton, No Direction Home, p. 313.

- ^ "You got a lotta nerve/To say you are my friend/When I was down/You just stood there grinning" Reproduced online:Bob Dylan. "Positively 4th Street". bobdylan.com. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p. 186.

- ^ a b "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2004-12-09. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Springsteen’s Speech during Dylan’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, January 20, 1988 Quoted in Bauldie, Wanted Man, p. 191.

- ^ Gill, 1999, My Back Pages, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Gill, My Back Pages, p. 89.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1987-11-01). "Recordings; Robbie Robertson Waltzes Back Into Rock". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, pp. 189–90.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 238–243.

- ^ "The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on individual bands in the Blonde on Blonde album. It's that thin, that wild mercury sound. It's metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up." Dylan Interview, Playboy, March 1978; see Cott, Dylan on Dylan: The Essential Interviews, p. 204. Reproduced online:Ron Rosenbaum (1978-02.28). "Playboy interview with Bob Dylan, March 1978". interferenza.com. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gill, My Back Pages, p. 95.

- ^ a b Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p. 193.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, p. 325.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 244–261.

- ^ Rolling Stone review of live album of concert said, "This isn't rock & roll; it's war." Fricke, David (1998-10-06). "Bob Dylan: Live 1966". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

{{cite web}}: Text "Rolling Stone" ignored (help) - ^ Dylan's dialogue with the Manchester audience is recorded (with subtitles) in Martin Scorsese's documentary No Direction Home

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, pp. 217–219.

- ^ a b "The Bob Dylan Motorcycle-Crash Mystery". American Heritage. 2006-07-29. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Cott, Dylan on Dylan: The Essential Interviews, p. 300.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, pp. 268.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p. 216.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p. 222–225.

- ^ Marcus, The Old, Weird America, pp. 236–265.

- ^ Helm, Levon and Davis, This Wheel's on Fire, p. 164; p. 174.

- ^ "Bob Dylan's 1967 recording sessions". Bjorner's Still On the Road. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ "Charlie McCoy's Bio". www.charliemccoy.com. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ^ Wadey, Paul (2004-09-23). "Kenny Buttrey :'Transcendental' drummer for artists from Elvis Presley to Bob Dylan and Neil Young". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Harris, Craig. "Pete Drake: Biography". Country Music Television. Retrieved 2008-09-25.