Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

August 14

Squiggly rain drops

I took a picture of the rain outside my window. It was both raining and sunny outside, so I thought that the raindrops would show up in the picture. They did, but they show up as squiggly lines. What is going on here? I took this shot through a window with a basic UV filter on. Camera settings: 1/90s, f5.6, 400 ISO. Any ideas? You will have to zoom into the picture to see the weird effect.

— Preceding unsigned comment added by Dlempa (talk • contribs) 00:31, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- They're lines because the shutter speed was too slow to "freeze" them. Since the squiggles are all the same shape, the squggliness is presumably the result of camera movement during the exposure. Deor (talk) 00:41, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- That's actually a pretty cool photo and I 100% agree with the above answer. Vespine (talk) 01:47, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- You see this effect very often in WWII era dogfight videos, such as here. The video in general may seem only mildly jerky, but the tracer bullets follow seemingly wild, zig-zagging trajectories. Someguy1221 (talk) 01:53, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- I suggest you use a timer and a stand, to prevent any hand shaking effect. Of course, the camera's own shutter motion might still cause some vibration. You also need a faster shutter speed, but that might make it too dark, so you will need to compensate for that. StuRat (talk) 01:58, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- I'd expect the circular part of the lines to be due to the shutter movement. An outside force wouldn't be so symmetric or return the camera to it's original position. Interesting to see Ssscienccce (talk) 02:07, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- But that circular motion occurs in the middle of each rain drop's motion. Wouldn't shutter motion be expected at the start and end, not in the middle ? StuRat (talk) 02:26, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, I'm wondering what mechanism could best explain the effect. First idea was focal plane shutters with two moving curtains, the slowing down of the first one and speeding up of the second; but that would show other differences I think. A digital camera can control shutter time electronically without the need for a physical shutter, it could be due to any kind of spring or electromagnet activated movement occuring during the exposure. it just seems too "perfect" to be due to hand movement. But that's just my opinion. Ssscienccce (talk) 04:04, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- But that circular motion occurs in the middle of each rain drop's motion. Wouldn't shutter motion be expected at the start and end, not in the middle ? StuRat (talk) 02:26, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- I think that this sort of picture is one in which a slower shutter speed would actually produce a more interesting result (if the camera tremor could be eliminated). If the shutter was so fast as to show dotlike drops, they would be basically indistinguishable from dust specks or other flaws in the photograph. Even to the naked eye, falling raindrops look rather more elongated than the ones in the photo, raising the question of what the "shutter speed" of the human eye is. Deor (talk) 02:38, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- @ Sturat, the transmission of the shutter shock to the camera's 'retina' moves at the speed of sound in the camera body, while the light moves at the speed of light. It is not inconceivable that the shock would show up in the image after the image was already partially formed. μηδείς (talk) 04:49, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Well it would be if the "retina" ie the film reacted instantaneously, but it doesn't. Taking the camera body as an aluminium alloy (speed of sound ~6500 m/s) and the distance from shutter to film as 20 mm, the time taken for shutter reaction to reach the film is of the order 3 microseconds. Time taken for the light, velocity of propagation 300,000,000 m/s, distance 20 mm, the time taken is ~7 picoseconds. Yep, light is darn fast compared to sound. BUT, the exposure time was 1/90 = 11 milliseconds. The nature of film is that the film exposure reaction is sensibly proportional to duration throughout this time. Typically, the shutter will take 1/3 the time to open, and 1/3 the time to close, ie ~3 milliseconds. So, the mechanical delay after the light is about 1/1000th of the shutter opening time, and about 1/3000th of the film exposure time. Clearly the the mechanical delay (and light delay) of of shutter rebound is negligible compared to image formation time - the film has been exposed less than 0.1% by the time the mechanical impulse arrives. The assumptions I've made about distances, shutter opening times etc are very rough, but it is inconceivable that they could be out by a factor of 1000x. Shutter rebound can only affect images by imparting an acceleration to the whole camera (camera sensibly a rigid body) with respect to the scene. Ratbone121.221.30.70 (talk) 05:38, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- @ Sturat, the transmission of the shutter shock to the camera's 'retina' moves at the speed of sound in the camera body, while the light moves at the speed of light. It is not inconceivable that the shock would show up in the image after the image was already partially formed. μηδείς (talk) 04:49, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Another part of the effect may be the fact that the sensor in your camera is scanned sequentially. There are some great pictures online of aircraft props taken with iPhones where the prop takes all sorts of interesting forms because it rotated through the lines of pixels as they were scanned. 209.131.76.183 (talk) 11:46, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

Thanks all for the comments and help! I guess I will continue to experiment. dlempa (talk) 14:53, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

What is the difference between a "larvae" and a "Nymph"?

What is the difference between a "larvae" and a "Nymph"? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:Contributions/175.140.180.186

- See the second and third sentences of Nymph (biology). Larvae, by the way is plural; it's "a larva", not "a larvae". Deor (talk) 02:42, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

Simply the mode of development. Nymphs undergo incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetabolism), while larvae undergo complete metamorphosis (holometabolism). Both are the juvenile stages of insects between egg and adult.

In nymphs, the growth of the juvenile stages is by gradual acquisition of features of the imago. For example, the first instar may already possess all the features of the adults, except the wings and the ability to produce sperm or eggs. Each successive molt and instar produces larger individuals and the beginnings of wings until the final molt when the imago finally emerges with fully developed wings and full sexual maturity. Note that hemimetabolic insects may also have a stage known as the "prolarva" or "pronymph", which is basically just an advanced embryo. This stage may occur inside the egg, though in some it may actually hatch as prolarva before undergoing their first molt and becoming the first instar nymph. But this time period of a prolarva outside the egg is usually very very short, lasting only a few seconds to a few minutes. The development through nymphs is believed to be the ancestral state in insects.

In larvae, in contrast, the adult features are more or less kept in an embryonic state. They often look like completely different organisms from their adult forms, with very different behavior. They also go through a stage missing in hemimetabolic insects - pupation - where the change from larva to imago is fast-forwarded. It has been hypothesized that this evolved sometime during the early Carboniferous due to the development of eggs with unusually small amounts of food reserves, thus necessitating restriction of growth and requiring the larvae to gather the resources for its final growth on its own. It is also generally accepted (the so-called "pronymph hypothesis") that holometabolic larvae are homologous to hemimetabolic prolarvae (i.e. it's an extended version of the prolarval/pronymphal stage in insects which undergo incomplete metamorphosis).

This is assuming that you're speaking solely about insects. As other animals also use those terms and others differently. Fish young, for example, are also called "larvae", while cephalopod young are called "paralarvae". Ticks, which are arachnids, actually have both larval and nymphal stages, though not in the same sense as in insects as their larvae are just miniature versions of their adults.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 03:38, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- A nymph that lives in a tree is a lot cuter than larvae that live in a tree: [1]. StuRat (talk) 04:30, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- You do realize that termites do not undergo pupation, and have nymphs, not larvae? Nonetheless, larvae are less attractive than nymphs. μηδείς (talk) 04:44, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

Higgs field vs. Dark Energy

What is the relationship between the Higgs field and Dark Energy? Would these balance off against each other to reduce the predicted Cosmological constant to its observed value? Hcobb (talk) 02:47, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Both can be explained with scalar fields, although dark energy doesn't require a particle, just a uniform potential as a physical property of spacetime (which is technically much simpler than a scalar field, but similar to the scalar fields used to explain cosmic inflation and the metric expansion of space.) Which predicted cosmological constant are you referring to? 75.166.207.214 (talk) 08:07, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- I'm attempting to explain the Vacuum catastrophe. Universe starts tiny and empty and then zero-point energy causes Inflation (cosmology) until the Electroweak symmetry breaking limit is reached. At that point a uniform field of Higgs bosons almost pushes through to carpet the universe wall to wall, but is just slightly overmatched by the zero-point energy and the result of the cancellation is the very tiny amount of Dark energy that we see today. Hcobb (talk) 15:31, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Higgs condensate contributes to the zero-point energy, so what you're proposing is really vacuum energy from the Higgs vs. other vacuum energy and cosmological constant. There's an interesting paper from 1980 by Kolb and Wolfram [2] in which they suggest that the vacuum energy of the Higgs condensate could be used to cancel out a cosmological constant; your suggestion goes along very similar lines. However, the famous factor-of-10^120 discrepancy is dominated by other fields, and the Higgs contribution is much too small to make a big difference. It generally makes things slightly worse. Even if you did manage to balance one large contribution against another to get a very small residual vacuum energy, you've only converted the matter into a terrible fine-tuning problem. The real problem is that we don't know how to calculate the vacuum energy even in a well-studied model like the standard one. --Amble (talk) 15:47, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- I'm attempting to explain the Vacuum catastrophe. Universe starts tiny and empty and then zero-point energy causes Inflation (cosmology) until the Electroweak symmetry breaking limit is reached. At that point a uniform field of Higgs bosons almost pushes through to carpet the universe wall to wall, but is just slightly overmatched by the zero-point energy and the result of the cancellation is the very tiny amount of Dark energy that we see today. Hcobb (talk) 15:31, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

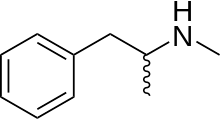

Please identify this pill

One side: G mark or something looking like an on/off button in an almost full circle.

Other side: ML 10 written on two lines.

Size: 5 mm in diameter and 3 mm in width.

Picture link - 1: [URL=http://picturepush.com/public/8971010][IMG]http://www2.picturepush.com/photo/a/8971010/img/8971010.jpg[/IMG][/URL]

[url=http://picturepush.com/public/8971088][img=http://www5.picturepush.com/photo/a/8971088/img/8971088.jpg][/url]

Additional information: The pill was found in my car - After it had been to Hamburg and also after I had been to a festival. It might have been one of my friends that have lost it.

I am pretty sure it's not one of these (Medication my dad is taking) :

zolpidem hexal venlafaxin orifarm furix digoxindak kaleorid tolmin delepsine retard litiumkarbonat oba — Preceding unsigned comment added by Azalin (talk • contribs) 08:58, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Only one way to find out. GC-MS it. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 09:03, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- If you're pretty sure it's something illicit, you could get a kit from DanceSafe or a similar organisation, or alternatively send it to EcstasyData.org or similar for testing. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 09:10, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Is it by any chance a hexagonal G ? (It would help to have a picture of that side, too). I found two round, white pills with hexagonal G's alone on one side: donepezil and voriconazole. Here's a 2 page list of those two and 16 other meds with a regular G alone on one side of a white, round pill: [3]. However, none of them matches the "ML 10" on the other side. StuRat (talk) 09:14, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- That G is the one used by Alphapharm on their tablets, and from their other tablets the 10 will mean 10mg. The product could well be Lumin or mianserin, an antidepressant, which is marked with MI.[4] Graeme Bartlett (talk) 10:15, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Sure looks like it: right link this time.. Ssscienccce (talk) 12:22, 14 August 2012 (UTC) oops.. fixed link Ssscienccce (talk) 15:26, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

Thanks a lot for the help - I believe it's either my Dad who lost it out of his pocket or in worst case - a friend having a depression - I wonder if that pill could be used as a recreational pill. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Azalin (talk • contribs) 23:18, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

Ternary mixtures and Raoult law

Considering two binary mixtures, one having negative deviation from Raoult law and the other pozitive deviation, what are the chances that a ternary mixture obtained from the two binaries be almost ideal (no deviation)? --79.119.214.49 (talk) 09:11, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- It's possible, but it's also possible that there will be a larger deviation in either direction. The deviation is governed by pairwise molecular adhesion and cohesion forces, and you are going from two disjoint pairs ((a+b) and (c+d)) to six pairs (a+b, a+c, a+d, b+c, b+d, c+d). I doubt there is a law that says they will always cancel out in aggregate, but molecular behavior is always a surprise one way or another. 75.166.207.214 (talk) 21:09, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

All particles moving at the speed of light

How accurate is it to say that even massive particles move at the speed of light, but because they're constantly bouncing off the higgs field they appear to move slower. Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 14:41, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Higgs field is theorised to give particles mass, and it is the fact that they have mass that prevents them travelling at the speed of light (as massless particles, such as photons, do). I don't know if particles "bouncing off" the field is the right way to think about it, though. I don't really understand the Higgs field, but I've never heard it described that way. The particles are interacting with Higgs bosons, and the end result of that is that they travel slower than light, but I don't think it is because they take an indirect path, which is what you are implying. --Tango (talk) 17:32, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- I think it's pretty close. The Higgs interaction that gives mass to the fermions is a three-way interaction between a clockwise circular polarized fermion field, a counterclockwise circular polarized fermion field, and the Higgs field. In order for this to preserve angular momentum the two fermion fields have to be propagating in opposite directions. The two fermion fields by themselves are massless. One way of describing this is that a quantum of energy in one of the fermion fields always moves at the speed of light but keeps switching to the other fermion field, reversing direction in the process, at a rate proportional to the strength of the Higgs interaction. (But the real behavior of the particle is a sum over all histories, including all possible times that that interaction could take place. So you shouldn't think of this back-and-forth motion as happening by clockwork, or at random, but rather in a continuous smoothed-out way.)

- The mass of the force bosons (W± and Z0) is more complicated, though, and I don't really understand it. -- BenRG (talk) 18:39, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- It's accurate in a non-rigorous, not-fully-quantum-mechanical picture of how particles behave. A closer analogy is light traveling through water: the light interacts with the water molecules in such a way that it ends up traveling about 1/3 slower than it does through vacuum. The interactions that give mass to a fermion or cause light to travel more slowly through a medium are coherent and continuous. "Bouncing around" could imply discrete scattering events, which would have different effects. --Amble (talk) 19:20, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- Between this subject and "dark matter" and all manner of other exotic things in physics, I'm waiting for science to decide that there is an Aether after all. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 23:41, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Higgs field has only a few practical differences from the traditional luminiferous aether involving Lorentz covariance and that it's a medium for fermion inertia instead of photon propagation, in my opinion, although I'm sure saying so is a serious heresy. 75.166.207.214 (talk) 03:33, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Higgs mechanism is not analogous to either light in water or waves in a luminiferous aether. In both of those cases the propagation happens at a fixed speed relative to the rest frame of the medium (water or the aether). Particles that get mass through the Higgs mechanism can move at any sublight speed—all sublight speeds are equivalent in vacuum. It's the particles that don't interact with the Higgs that move at a fixed speed. The nice thing about the back-and-forth explanation of the Higgs mechanism is that it gives a natural reason why you can't exceed c. Everything actually moves at c all the time; you can end up with a slower average speed if you keep changing direction, but you can't end up with a faster average speed. -- BenRG (talk) 05:59, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Not exactly: the propagation of light in water is dispersive, and photons can be described as having an "effective mass" in a material. But my main point is that the interaction between the light and water, or a particle and the Higgs field, is not like the random scattering interactions suggested by "bouncing off." Instead, you get a propagating mode that's a coherent combination of the two. That's true for light in water and for the Higgs mechanism. The difference is in the details of the dispersion relation. --Amble (talk) 08:37, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Higgs mechanism is not analogous to either light in water or waves in a luminiferous aether. In both of those cases the propagation happens at a fixed speed relative to the rest frame of the medium (water or the aether). Particles that get mass through the Higgs mechanism can move at any sublight speed—all sublight speeds are equivalent in vacuum. It's the particles that don't interact with the Higgs that move at a fixed speed. The nice thing about the back-and-forth explanation of the Higgs mechanism is that it gives a natural reason why you can't exceed c. Everything actually moves at c all the time; you can end up with a slower average speed if you keep changing direction, but you can't end up with a faster average speed. -- BenRG (talk) 05:59, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Higgs field has only a few practical differences from the traditional luminiferous aether involving Lorentz covariance and that it's a medium for fermion inertia instead of photon propagation, in my opinion, although I'm sure saying so is a serious heresy. 75.166.207.214 (talk) 03:33, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Between this subject and "dark matter" and all manner of other exotic things in physics, I'm waiting for science to decide that there is an Aether after all. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 23:41, 14 August 2012 (UTC)

August 15

Proton equilibrium distance?

I was wondering what is the distance between two protons where gravity attraction would be exactly opposite the electromagnetic repulsion force? Or would the distance be so small that the nuclear forces would also have to be taken into account?49.176.68.92 (talk) 02:44, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- A little googling reveals that this is a popular homework question, sorry. 75.166.207.214 (talk) 03:29, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- If it is a homework question, it's a trick one. Both gravity and static electric repulsion fall off at the same rate, being proportional to 1/r2. Thus, the electric force is always stronger than the gravitational force. If you were to try to solve this question rigorously, you would find the r such that Gmm/r2 = kqq/r2, which naturally leads you to Gmm=kqq, which, being untrue, leads to an answer of: Not in this universe, kid. Someguy1221 (talk) 03:43, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Just to clarify Someguy's correct answer, the equations he uses there are Newton's law of universal gravitation and Coulomb's law. As he noted, the relationship between force and distance for both of these phenomena is the same, which means that the equilibrium is either at zero (gravity is stronger), every distance (both equal each other), or infitinty (electrostatic replusion is stronger which is the case for two protons). In addition to your example of two protons, for any given set of identical particles any one of these three conclusions may hold, but it may never have a unique finite distance where they are at equilibrium. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 04:04, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- If it is a homework question, it's a trick one. Both gravity and static electric repulsion fall off at the same rate, being proportional to 1/r2. Thus, the electric force is always stronger than the gravitational force. If you were to try to solve this question rigorously, you would find the r such that Gmm/r2 = kqq/r2, which naturally leads you to Gmm=kqq, which, being untrue, leads to an answer of: Not in this universe, kid. Someguy1221 (talk) 03:43, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

The same problem but now take into account the finite Debye length, e.g. consider two protons in the interstellar medium. Count Iblis (talk) 19:40, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- In the intergalactic medium the charge is effectively screened at 10m, so the point where the force due to electrostatic repulsion and gravitation between those two particles cancel out is 10m, but the whole charge screening effect is only there because of the other mobile charge carriers which have turned this into an n-body problem to calculate the point where they actually feel no net force at all. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 20:12, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

Hydrogen isotopes

Why do the hydrogen isotopes 5H and 6H have longer halflives than 4H? This seems to imply that they're more stable. What's causing that stability? 203.27.72.5 (talk) 05:46, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Several ideas to consider. First, with respect to "more stable", reaction rate depends both on the (in)stability of the components involved and also the difficulty of accomplishing the reaction. It's possible that a reaction is kinetically slow(er than you might think) because it's a more complicated process regardless of how thermodynamically unstable the reactant might be. For example (this is purely my hypothetical for the case at hand) maybe it's simpler to eject a single neutron (decay of 4H) than the multiple-neutron decay processes of some other isotopes? Note that the decay-mode(s) column in the table in Isotopes of hydrogen does not exactly match the extended discussion of each isotope earlier in the article. The actual "stability" (intrinsic energy) of the nucleus is directly knowable by looking at the binding energy from the given isotopic masses. Interestingly, 4H hits a double-magic number, a fact that gives this isotope more stability and longer half-life than expected by other simple trends. Might be useful to check the references related to the isotopes of interest in the article to see if there is any commentary and to make sure the reported data values actually are correct. DMacks (talk) 07:28, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- If the emission of a single neutron is more kinetically favoured than a multiple emission, then shouldn't the hydrogen-5 and hydrogen-6 decay via single neutron emission to hydrogen-4 and hydrogen-5 respectively just as fast or faster than the hydrogen-4 decays to tritium? The source cited for halflife and decay modes in the extended discussion of 4H, 5H and 6H has some qualifying remarks for 5H that I don't understand. It also says that 5H only decays via double neutron emission, whereas 6H decays via single and triple neutron emission in unknown proportions. This all totally contradicts the table that doesn't cite its source(s) at all, except all of the halflives are in agreement as far as I can see. As for the quality of the source itself, it's an article from Nuclear Physics A, so I imagine it's reasonably authoritative. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 08:05, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Also, 4He is doubly magic, not 4H. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 08:16, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Crap, misread that page...I really need to sleep and/or get more coffee. DMacks (talk) 08:24, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Given the high stability of 4He, it's suprising that 4H doesn't emit a beta particle to form that highly stable daughter product, rather than forming a free neutron and tritium, both of which are unstable. The more I look into all of this, the weirder it seems. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 08:22, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

Stellar Transition Paradox?

Suppose one were to accelerate a spacecraft to some appreciable percentage of the speed of light, with respect to some "stationary" reference frame. At some point, an observer in that frame measures the mass of the craft to be just beyond the threshold for stellar ignition. And yet, with respect to the spacecrafts reference frame, there is no tangible increase in mass. Obviously, the craft cannot transform into a star in one reference frame and remain unchanged in another. So what am I missing here? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 66.87.126.39 (talk) 06:32, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- That it's a (potential) star's rest mass which much exceed the ignition mass threshold for it to fire up ? StuRat (talk) 06:36, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- That's incorrect. Gravitation is a function of mass-energy, and it's the gravitation that compresses the core to initiate fusion. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 06:43, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Self-gravitation, which is what is relevant for stellar ignition, is a function of mass-energy in the rest frame of the object in question. If you are interested in the gravity felt by the observer, then it is more complicated, but if you want the gravity felt by one part of the spacecraft due to another part of the spacecraft, with both parts moving together, then it is all nice and simple. --Tango (talk) 12:10, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- That's incorrect. Gravitation is a function of mass-energy, and it's the gravitation that compresses the core to initiate fusion. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 06:43, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- (edit conflict)How would they measure the mass? The whole idea of relativistic mass is deprecated by experts because it is so easy to misunderstand. Dbfirs 06:40, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- For an explanation of the difference between rest mass and relativistic mass, which as explained above is the key issue here, see Mass in special relativity. Red Act (talk) 15:29, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

Okay, so an increase in relativistic mass would only equate to a higher energy content in the system relative to the observer, but not, say, it's gravitational force. Is that correct? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 66.87.127.160 (talk) 16:08, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- In general, it doesn't even make sense to ask by what factor the gravitational force produced by a body changes if the body is rapidly moving, for a couple reasons:

- First of all, Newtonian gravity doesn't in general give the right answers when dealing with very rapidly moving objects, even if you try to make special relativistic corrections to Newtonian gravity. Instead, you in general need to use general relativity. And in general relativity, gravity isn't even a force (i.e., gravity isn't something that produces a proper acceleration), although it can be treated locally as a fictitious force. See Fictitious force#Gravity as a fictitious force.

- Secondly, force is a vector quantity, not a scalar, and all components of a force do not in general transform identically under a Lorentz transformation.

- You also have to be careful about what you're expecting force to mean about a relativistic system, because unless an object's acceleration is orthogonal to its velocity, the equation f=ma, with f and a being three-dimensional vectors, does not in general hold, regardless of whether m is the rest mass or the relativistic mass. Instead, what does hold in general is F=mA, with F the four-force, m the rest mass, and A the four-acceleration. m being the rest mass in F=mA is one of the reasons why rest mass is a more useful concept than relativistic mass.

- Despite the above caveats, it does become possible to meaningfully answer your question if you make some simplifying assumptions: Assume that object 1 and object 2 are moving slowly relative to each other, and assume that in the “lab” frame, at some instant of interest object 1 and object 2 are at the same x coordinate, and are moving in precisely the x direction at the same huge velocity. In that case, even though the relativistic mass of object 1 is larger than its rest mass by a factor of γ, the force that it exerts on object 2 is actually smaller as measured in the lab frame than in the objects' rest frame, by a factor of 1/γ. The three-dimensional equation f=ma does hold in the lab frame in this situation, with m being object 2's relativistic mass, which implies that object 2's acceleration is smaller as measured in the lab frame than in the objects' rest frame by a factor of 1/γ2. The smaller force and smaller acceleration as measured in the lab frame are a consequence of time dilation. Red Act (talk) 18:06, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- What you're missing is that, although mass is (usually) a reliable proxy for the conditions of stellar ignition, it's not the proximate cause of stellar ignition. That is, it isn't the mass itself which causes the stellar ignition, but rather the secondary effects (e.g. increased pressure and density) that are typically correlated with being a gravitationally bound system of gas in hydrostatic equilibrium exceeding a certain mass. When you go at relativistic speeds, you increase mass, but you don't necessarily affect those secondary things which are the actual cause of stellar ignition. -- 205.175.124.30 (talk) 21:05, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

How is the LHC able to sustain 5 trillion degree temperatures?

Forgive if the question is elementary, but I've searched both Wikipedia and the internet at large, and I haven't been able to find a suitable answer. The Large Hadron Collider has been in the news again, this time for creating what a Nature.com blog calls "the hottest manmade temperatures ever." In the article, it's estimated that this quark-gluon plasma, the source of the record-hot temperatures, reached 5.5 trillion degrees Celsius.

My question is: how could the LHC, or anything manmade for that matter, sustain temperatures that are apparently exponentially hotter than the center of the sun? The Wikipedia article on the LHC refers to "superconducting magnets," but I still don't understand how magnets alone can keep the components of the LHC from melting in the presence of trillions of degrees.

Thank you for your help! 65.6.139.251 (talk) 13:21, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Because the amount of energy is put into only a few particles. Temperature generally refers to the average kinetic energy of particles. When you heat, say, a bowl of soup in a microwave, you're putting a relatively small amount of energy into an ENORMOUS number of particles, and the end result is you heat it up by a few degrees. At the LHC, they're putting a huge amount of energy into just a couple of particles, making it much easier to get those numbers skyrocketing. Goodbye Galaxy (talk) 13:41, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- For that reason it is really an abuse of language to call it temperature. --BozMo talk 15:39, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Particle physicists are usually very careful to define temperature, and specify which particle or particles they are measuring when discussing temperature. Personally, I think it's more meaningful to discuss energy per particle, rather than temperature, because energy is a lot less ambiguous. You can simply multiply the Boltzmann constant by the temperature to get an energy quantity. Now, the question is, "to which particle or ensemble of particles does that energy value apply?" It isn't always obvious; and it's not exactly valid to say "each particle has that much energy." This conundrum makes clear that the description of temperature requires some contextual qualification. In an ordinary gas ensemble, we call that the "average kinetic energy of each gas molecule,"... but this description only applies in trivial textbook examples.

- In this case, the value comes out to half an MeV - or, about the rest mass of the electron. So, a more scientifically rigorous publication might have said, "by colliding heavy ions, the new TeV facility at CERN has been able to impart kinetic energy to a relativistic electron equal in magnitude to its rest mass," a landmark accomplishment that few outside of the formally-trained physics community would appreciate. In fact, reviewing the speaker's publication, it looks like he's seeking parity violations in relativistic electrons. If you're interested in reading more, here is the website of Steven Vigdor, the Brookhaven scientist who led the LHC team in the latest experiment; and here is the website of website of Brookhaven Senior Scientist Dmitri Kharzeev, the scientist whose work was referenced in the Nature blog. It appears that the newest results were at ALICE in France/Switzerland, while prior high-temperature collision work was done at RHIC in New York. Nimur (talk) 17:28, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- From an unrelated white-paper, here's a better description than I could concoct - because it's written by a lab-director actively working in the field of high-energy heavy ion collisions: ..."the spectra of thermal photons radiated during the collisions, in combination with hydrodynamics calculations, indicate that the matter equilibrates at an initial temperature >~300 MeV (or 4 trillion Kelvin, about twice the QGP transition temperature predicted by lattice QCD), and in no more time than it takes light to traverse a proton." In other words, the temperature is very very high. Nimur (talk) 17:38, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- For that reason it is really an abuse of language to call it temperature. --BozMo talk 15:39, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- It doesn't sustain those temperatures. They exist for fractions of a second when the collisions happen, but that's all. --Tango (talk) 23:08, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

Why only one extant species of human

I was having a discussion with a friend on the concept of race, and I explained to him that race or subspecies does not exist in humans. In fact cro magnon which is probably more genetically distinct from any living human today is even considered to be the same subspecies as we are. So then he asked why this is. Why is it that among other animals, you can see a wide variety of different species and subspecies but we are the only surviving member of the genus homo when sapiens are known to co-exist with other humans such as neanderthalis and erectus in the past.

My attempt at an explanation is as follows. If a lifeform proliferates, its gene pool tends to become more homogeneous. If sapiens for example were to inflitrate territory occupied by erectus, they would inevitably come into conflict because they compete over the same exact resources. As history has shown, invaders also tend to rape the indigenous population and mix with the females, while killing off the males. So some X-linked traits should be absorbed into the invader, but for the most part, the invader's species is dominant (assuming they brought sapiens females with them, which they probably did). Also since they are so closely related, diseases that the invader possesses are likely to infect the defender's population and "help" kill them off. Using an analogy, if there was a "super wolf" that was capable of proliferating rapidly and spreading across the globe, it's likely that there would be only one race of wolves.

How is my explanation? Pretty close? Any problems? 148.168.40.4 (talk) 13:35, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Plausible but I think you would need to find better stats on how many other animals have a variety of different species and subspecies and see if you could account for others before getting beyond plausible. None of the human behaviours you mention seems to be utterly unique to humans. --BozMo talk 15:36, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- The other lifeform that I found that comes close to being "super" and proliferated across the globe seems to be the Orca. According to the article, it seems that there could be several populations that are tentatively being categorized into subspecies or even species. I'm not entirely sure, but if I were to guess at an explanation for that divergence, it would be due to those populations being relatively isolated from each other for longer periods of time than human populations were. 148.168.40.4 (talk) 17:08, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

This - " If a lifeform proliferates, its gene pool tends to become more homogeneous." - is problematic, and not generally true. See speciation, and specifically sympatric speciation. Your description of competition and interbreeding among early Homo is otherwise basically consistent with the professional consensus on human evolution. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:17, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- It's also not unconroversial how organisms are assigned to various Linnean classifications. There have been some who have argued for a single genus encompasing both humans and chimapnzee species (essentially combining the Pan and Homo genuses). The decisions on how to assign various groupings of animals to any one particular species/genus/family/whatever is somewhat arbitrary, and the "rules" so fuzzy around the edges as to be ultimately not very helpful. The only reason why there is only one "Homo" species extant is that taxonomists have only assigned one group of critters to the "Homo" genus. Any other explanation misses the point of taxonomy. --Jayron32 16:22, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- That's very true SemanticMantis. I guess I should rephrase how I put that. It seems the consensus among scientists is that sapiens left Africa about 60,000 years or so ago, and in just a relatively short period of time managed to proliferate all across the planet. Since our species doesn't reproduce quickly like fruit flies do, speciation amongst humans would require a lot more time and would require those populations to be isolated. So maybe I can rephrase it as such,

- "If a slow reproducing lifeform proliferates quickly, its gene pool tends to become more homogeneous." 148.168.40.4 (talk) 17:04, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- However, you cannot base such a broadly worded proposal on a single species, being Humans. Human genetic diversity is highly constrained due to some historical population bottlenecks relatively recently: Toba catastrophe theory is one of them. Homogeneity among Humanity may be due to an event like that, and not to any particular principle of population genetics. --Jayron32 17:08, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- The part about disease works both ways. The Sapiens could have just as easily been killed off by diseases they caught from the Cro Magnon. No matter how "super" an organism supposedly is, humans still have adaptive immune systems that are much less effective against pathogens that we've never been in contact with before. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 20:47, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Except that modern humans, if more widespread and in contact with each other, would have developed more immunity. Thus, when coming into contact with an isolated Cro-Magnon group, they would be far more likely to die from a disease the modern humans carried, just like with Native Americans when Europeans arrived. StuRat (talk) 21:15, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- I don't see any reason to suppose that early Homo Sapiens were in frequent contact with one another before the advent of civilization. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 21:51, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- There's evidence of trading going way back, such as one group possessing items not native to their area. StuRat (talk) 23:52, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- I agree with the lack of isolation of hominid populations as one cause, since modern humans either out-competed or outright killed other hominids as they came into contact with them. However, this also requires that we all be "generalists". Presumably, if each group if humans filled a unique niche, and didn't compete with each other, we wouldn't feel the need to kill off the competition, either. We would end up like Darwin's finches, which each had a different-shaped bill to get nectar from a different flower. StuRat (talk) 21:11, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- I am thinking it is human language that gave humans the advantage in coordinating hunts/raids/skirmishes (in addition to warning kin of danger) which would help in displacing existing hominid populations as they moved into new areas. Is there any evidence that any of these other hominids had language? We should also note that humans are known to have killed off many many other species as they moved into new hunting grounds, and these other hominids were likely seen as meat much like any other. SkyMachine (++) 21:18, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- But if language was so important, how do you explain so many whales species, when they have such a well developed language ? StuRat (talk) 21:45, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Cetaceans do NOT have a well-developed language. That assertion is probably one of the greatest popular misconceptions in lay science, and is promoted, all evidence to the contrary, by hippy green types. Whales have a language capability about the same as other herd mammals, like goats and elephants. Language means having dozens or hundreds of sounds which uniquely represent some noun or activity and are joined by a grammatical structure. Chant type songs are not good examples of language, as they are not giving much information to anyone else. It might be the case that a whale can make a sound which identifies himself (as in a name). When I see OTHER whales use this sound, as if to say “Willy is coming over tonight”, I will be impressed.In[the talk page for Cetacean intelligence] I proposed a good experiment to see if cetaceans can communicate like humans. You can read it there, but basically it involves two dolphins (or whales or whatever) having to confer as to where in a marine cave some food has been stored, so one of them can go there and spring the device which stores it. I believe that no scientist thinks that these animals would be able to do this. Myles325a (talk) 04:59, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- But if language was so important, how do you explain so many whales species, when they have such a well developed language ? StuRat (talk) 21:45, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- What a highly subjective nonsensical rationale. If all people thought like you, humans wouldn't bother learning other languages, because you'd consider any language which doesn't sound like your native language gibberish. Heck, even with sophisticated equipment, we still have trouble actually hearing what cetaceans are saying as much of it is too fast and waaay out of hearing range. Have you ever seen footages of dolphins hunting prey? Explain then how they coordinate extremely complex cultural (i.e. learned) behavior without some form of language?

- Of course they can never be as complex as human languages. No other animal has that capability. The degree of complexity is relative to other forms of communication among other organisms, and they certainly ARE NOT on the same level as herd animals. Anthropocentrism at its finest.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 10:33, 18 August 2012 (UTC)

- Your experiment sounds clever to you, so let's apply it to humans. Imagine I'm an alien that can fly, have no sense of sound, and communicate through color patterns in my skin. I can also see colors far beyond the ultraviolet and infrared range and eat through direct absorption of vapors through pores in my skin. I build structures on top of tall rocks where I keep xxzzfltbltbzz food dispenser and an instrument that prevents buildup of poisonous xxvavsss in my gut. Both of the latter are everyday essential things in my alien culture. All members of my species build those structures and possess those instruments, even the very young, only the mentally disabled don't.

- Imagine if I picked two humans put them in a laboratory with tall rocks and the parts needed for building the structure as well as the instruments. Imagine to my surprise when the humans don't build a structure on top of the tall rock. Instead they do strange things like open those strange little holes at each other and waving their appendages and pushing the things about. Their skin don't even change color at all and they can't even make the instruments work (you shake it thrice and jiggle the thungmxzzzyzxt to the right and pull the huggvzasrrrt, and then turn your skin color greenish-purple). Would I conclude that humans aren't intelligent? By your reasoning, yes I would.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 10:52, 18 August 2012 (UTC)

- Whales for the most part generally hunt things smaller than themselves. Humans go for a range of prey, many being larger than themselves which require coordinated group hunting to take down, so language has a much bigger impact in this scenario. SkyMachine (++) 21:52, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Some whales use highly coordinated hunting methods. Humpback whales designate one whale to go low and blow a bubble ring, that causes the fish above to form a bait ball, which all the whales then devour. Orcas will coordinate an attack on larger whales, say to drive a baby whale away from the protection of the pod, so they can kill and eat it. StuRat (talk) 23:49, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Good point, yes it is amazing what millions of years of evolution by natural seletion can achieve. Whales are not killing whales though, are they? However, with humans it was all very rapid (<1million years) so a technological/societal emergence is valid to speculate on as the reason why they blitzkrieged the close competition. SkyMachine (++) 04:06, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- In the case of orcas (killer whales), they certainly do kill other whales. StuRat (talk) 04:19, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

Saying that early modern humans (Cro-magnons) are considered the same species as people today doesn't really mean much. Spacially isolated organisms of the same species can become separate species over time, and that can be tested by looking at the viability of hybrid offspring. Temporally isolated organisms such as us and Cro-magnons may have experienced enough genetic drift and selection pressure in the interim that we would fail such a test, but it cannot be carried out anyway. You may also be interested in Species problem. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 21:45, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Lack of isolation, as mentioned above, is the main issue. Behaviorally modern humans have bee around since just before the Toba supervolcano bottleneck at 75,000 bp. Genetic, archaeological and linguistic evidence all converges at that date for the origin of extra-African modern humanity. The Neanderthals and ebu gogo did not long survive intense contact with H sapiens sapiens. μηδείς (talk) 22:30, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Not meaning to nitpick, but a couple of caveats here. "Behaviorally modern humans" is by a nature a pretty subjective term, since many aspects of behaviour which do not leave paleontological record are very vaguely understood as to exactly when and how they arose. Language, for one. It's one of those situations where most serious researchers will just tell you straight up it's a bit of a guessing game and though theories abound, none has concrete empirical evidence. There are plenty of examples where for other aspects of human psychology and culture, once we get into prehistory, the trail runs cold. Anatomically Modern Human is the much more common and (somewhat) less debated term. Theories for this have ranged considerably over the years from about 75,000 to 200,000 years, but my (admittedly impressionistic and in no way compiled or sourced) perception over recent years has been that somewhere around 140,000-160,000 years ago seems appears to be winning out as a likely rough arrival point of the distinct species. Also, the Toba Extinction hypothesis is not really settled fact by any measure. A lot of researchers agree some sort of bottleneck likely occurred, but timing and cause are debated. Snow (talk) 02:58, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Chimpanzee-human last common ancestor is estimated to be around 6 million years ago. What are some of the most "isolated" living species measured by the estimated age of the last common ancestor to another living species? PrimeHunter (talk) 00:51, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Apparently the Nile crocodile separated from the rest of crocodylus during the pliocene (5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago). But again, there's no guarrentee that a modern Nile crocodile could produce viable offspring with one from the distant past. And besides, my DeLorean is in the shop. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 02:06, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- That's not a very helpful question in the case of humans. Some "living fossils" (they'd be called language isolates in linguistics) only have very, very, very distant closest relatives, like the aardvark, Amborella trichopoda, Latimeria, and Ginko biloba. μηδείς (talk) 02:24, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- That's a hard question to answer. If you classify placozoa as a single species, as some biologists do, they probably separated from every other living species well over 600 million years ago. You can't get much farther back without going to single-celled organisms, where the very concept of a species becomes problematic. Looie496 (talk) 02:24, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- To the OP, your take is basically consistent with one of the leading theories on the matter. Note that a number of human subspecies did evolve in isolated global regions and coexist for significantly long periods of time. However, when Homo Sapiens sapiens came on the scene, they occupied a significant overlap in ecological niche with these species but they spread faster and had significant advantages over their predecessors. Though in the last couple of years it has come to be considered established fact that at least two of these other species of primate seem to have interbred with Homo Sapiens. Note that the degree to which disease played a role is debatable; the reason that huge epidemics arose after contact between historically recorded groups of humans was that some of these people had been involved in extensive animal domestication and had inherited some of their diseases but also immunities against them -- they shared the diseases with those they came into contact with those who had not been in close contact with other animal species and thus had not been a vector for mutated stains of animal-originating diseases to give back (hence why Europeans did not pick up significant new diseases from the America after contact, but their diseases ravaged the Americas (for a fuller discussion of this process, Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel is a can't-miss read; his The Third Chimpanzee also treats the origin and spread of anatomically modern humans and how they arose from animal origins and, to a limited extent, how they competed with their immediate predecessors). For more general info on the subject matter of what separates individual but closely related species and how they can co-evolve and compete, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory is a great, if sometimes clinical, reference. Snow (talk) 02:58, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

Myles325a back live. To OP: It is eye-opening to see the number of hypotheses presented above as matters of record. I’ll do the QI thing and put up the “Nobody Knows” flag. Some scientists BELIEVE that we (Sapiens) wiped out or out-competed Neanderthals. But nobody knows; it is a wide open question. And there were dozens of hominoid beings in the past. Did we wipe them all out, including the really isolated ones like the so-called “Hobbits”? I don’t think so, but then - nobody knows. Recently, I started a list of wide-open questions in science which can be found here [myles’ list of wide open science questions]. It is no. 3 there, along with some comments and additions. Myles325a (talk) 05:21, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- One minor correction to the OP: I don't think it's the case that Cro-Magnons would be more genetically distinct than living populations. Cro-Magnon fossils are less than 50,000 years old, so after the emergence of modern humans from Africa and the colonization of most of the Old World, including Australia. I don't know if there has been any genetic analysis of Cro-Magnons, but I would expect them to be less distinct than some modern populations. John M Baker (talk) 20:08, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

West Nile vaccine for humans

This is a general question related to the article West Nile virus and not a request for medical advice. In the US, West Nile disease seems to be in a resurgence this year, with Texas recently declaring an emergency due to the rising number of infections and deaths. The CDC says there is a vaccine for animals, but no vaccine for humans.[5] "Chemirivax-West Nile" vaccine was in the news from 2002 through 2008. It was a vaccine made from Yellow Fever vaccine by adding something from the West Nile virus, and was found safe in human trials and to protect from the virus in animal trials. Authorities sometimes spray poison from trucks and airplanes to kill the mosquitoes, over the objection of residents of the areas, and advise people in affected areas to stay indoors, or to douse themselves with possibly toxic repellants when spending time outside, so a safe and effective vaccine would be of considerable interest. Over 100 people get a mild asymptomatic infection for every severe infection, and studies of the African population imply that a history of such exposure might produce antibodies which confer some protection against future infection. a)Is there a test available clinically to determine whether an individual has such antibodies from a past mild infection? b) What is the status of candidate vaccines which are being developed for human use?Are any in Phase 3 trials? Edison (talk) 19:11, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- A report of a Phase 2 clinical trail for the Chemirivax vaccine was published last year, see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3086439. Several other vaccines are in earlier stages of testing. I can't find any mention of a Phase 3 trial. Looie496 (talk) 19:33, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Checking into whether this involved media exaggeration, I found that Texas has half of the total U.S. reported cases so far this year [6] and the number of cases is more than twice the number reported at this point last year. Rmhermen (talk) 20:31, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- The NY Times in 2003 said that every infected person becomes immune to the disease for life. Is that reliable sourcing for adding the info to the West Nile virus article? Edison (talk) 22:14, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- The Times would likely have quoted some authority. You'd be best off saying something like: "The CDC, according to the NY Times, has said that...." μηδείς (talk) 02:15, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter photo of Curiosity

This photo of the Curiosity rover parachuting down to the surface of Mars, taken by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, has been circulating quite widely.

Does anyone know of a version of it without the white box around the rover? (Yes, I could edit it out with Photoshop, and I may have to for my intended purpose, but if I could find the original, all to the better.)

Thanks. --Mr.98 (talk) 20:14, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Ah, after more poking around, I found it! It's the big half-gig file on the bottom — you have to play a little game of Where's Waldo, but the rover is there, unmolested by annotation. --Mr.98 (talk) 20:32, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Can I ask why you objected to the white box ? StuRat (talk) 23:44, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

Increasing human intellect?

I was told today by an unbearably cocky teenager (awaiting his A-Level results) that it was scientific fact that people are more intelligent now than they were 100 years ago. As I'm just over half that age, I took it as a bit of an insult. Is there any evidence available, that humans are NOT more intelligent now, they just know different stuff? I know disproving an assertion is harder than proving one but I live in hope. I want something to wave under his nose in a triumphant fashion please (Vanity, vanity, all is vanity!). Alansplodge (talk) 22:23, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- See the Flynn effect. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 22:31, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Sure they are. That's why nobody goes to war anymore. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 23:00, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Assume that the youngster is correct, and tell him that in correspondence to his increased intellectual capability, you will consequently expect improved overall performance, productivity, and innovation from him and other representatives of his generation. Using quantitative psychometrics such as the standardized testing model, one can expect to rapidly accelerate the progress of our species. Be sure that he understands that you hold him personally responsible for accomplishing that task. Nimur (talk) 23:01, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Well, back in the Middle Ages, average intelligence might very well have been less. That is, while people were presumably conceived with the same mental capacity as they have now, a combination of malnutrition, drinking alcohol, and lack of mental stimulation likely resulted in diminished capacity by adulthood. Of course, none of this applies to the small group of wealthy people (except perhaps the alcohol), who could be as brilliant then as now.

- TV might have represented a low in mental stimulation for modern people (with a few exceptions, like PBS shows), but more interactive forms of communication might again have started to improve things. StuRat (talk) 23:40, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- Maybe yes, but not necessarily in the way he means. There's quite a bit of evidence that suggests that severe perinatal and childhood malnutrition contributes to lower adult IQ[7][8][9]. If we can then show, in a population, that malnutrition has decreased over the time in question, I don't think it's a huge jump to say that the number of people in that population with IQs lower than they would normally be would be reduced - that would raise the average IQ of that population, and so one could say "of this population, the mean IQ has increased over this period". This paper says that is the case for Vietnam (over the 1990 to 2004 period). So, waving one's statistical hands a bit, I think one can say e.g. "the average IQ of people born in Vietnam in 2004 is greater than those born in 1990". But I assume you and he were raised in the UK, not a developing country like Vietnam. Those papers I cited at the start all talked about medically significant malnutrition, and I don't think your 1960s meat-and-two-veg upbringing was really materially less nutritious than his 1990s turkey twizzlers diet. I can't find a source that says whether the overall proportion of people in the world who are malnourished is less than it used to be, but my strong inclination is that it is. If that is true, I think you can say "humans are more intelligent now", but not that "Britons are more intelligent now". So you had a slight statistical advantage over the "average human" when you were his age that has been eroded some for him. Whether he should be happy or sad about that is another matter. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 23:49, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- As I understand it, there's quite an epidemic of binge drinking in the UK now, which may lower IQ a bit. StuRat (talk) 23:57, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- If your mother drank heavily while pregnant with you, or if you drink a lot during childhood, that might impact IQ. I doubt it has much effect in adulthood, though. The "alcohol kills brain cells" thing isn't really true. --Tango (talk) 00:21, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- As I understand it, there's quite an epidemic of binge drinking in the UK now, which may lower IQ a bit. StuRat (talk) 23:57, 15 August 2012 (UTC)

- But it's probably Alansplodge's generation doing the binging. This paper (p9) from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation shows steady-ish rates from the late 1970s, but for a marked increase in wine consumption. That graph stops in ~2005: UK drinkers now drink 13% less than 2004. The Rowntree paper (p6) says excessive consumption among young adults has fallen since 2000 (back to 1988 levels - so before that steep spike), but increased in older age groups (that's who's drinking all that extra wine). So I think there's little evidence that UCT's generation in incurring much more alcoholic brain damage than Alansplodge's. Maybe from Teletubbies, but not drink. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 00:24, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Ya, those Teletubbies could turn anyone into a vegetable. But I do think binge drinking does more damage than steady drinking. Has the rate of binge drinking increased ? StuRat (talk) 00:31, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Epidemiology of binge drinking#United Kingdom says "Among young people (under 25), binge drinking (and drinking in general) in England appears to have declined since the late 1990s according to the National Health Service." Binge drinking#Central nervous system suggests the evidence on the effects of binge drinking on mental processes isn't very decisive. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 00:49, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Technology builds on previous technology, so there may be an illusion that people are getting more intelligent, but that doesn't mean they're getting any "smarter". To quote Will Cuppy, "The Dark Ages were called the Dark Ages because people then weren't very bright. They've been getting brighter and brighter ever since, until they're like they are now." ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:58, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

Thank you one and all for your replies. I'm rather cheered by the detail of the "Flynn effect" article which says that only the dimmest folk have got brighter over the last century, those of average intelligence have not improved and the most intelligent may actually be getting less so. Alansplodge (talk) 18:30, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- I think it's time for a little gratuitous Lysenkoism, courtesy of epigenetics. [10] Wnt (talk) 10:18, 17 August 2012 (UTC)

- It also depends on how one defines "intelligence". Take one of these supposedly super-smart characters from today and plunk them into, say, England in the year 1066, and see how their high-tech intelligence would serve them, i.e. how long they would survive. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 14:23, 17 August 2012 (UTC)

- Indeed. I remember from childhood an elderly friend of my parents who could mentally add three long columns of figures simultaneously; those columns being pounds, shillings and pence which involves adding-up pence in base 12 and shillings in base 20. An impressive feat and very useful in an office at one time, but quite pointless today. Alansplodge (talk) 16:28, 17 August 2012 (UTC)

- That reminds me of the self-service restaurant in Blacklers (Liverpool) many years ago (before modern tills) when a woman with Savant syndrome was employed to add up the total cost just before the till. Dbfirs 07:46, 18 August 2012 (UTC)

- Indeed. I remember from childhood an elderly friend of my parents who could mentally add three long columns of figures simultaneously; those columns being pounds, shillings and pence which involves adding-up pence in base 12 and shillings in base 20. An impressive feat and very useful in an office at one time, but quite pointless today. Alansplodge (talk) 16:28, 17 August 2012 (UTC)

August 16

How are the life cycles of Mollusks and Insects alike?

How are the life cycles of Mollusks and Insects alike? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 175.140.183.44 (talk) 00:51, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- See Insect#Reproduction_and_development and Mollusca#Reproduction. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 01:14, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Why, do you have crabs ? ...or perhaps an unfinished homework assignment ? StuRat (talk) 01:35, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Very little at all that they do not share with all animalia, except for the fact that they lay eggs and have protostome development. μηδείς (talk) 02:13, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- For starters, they're born (or hatched or whatever) and eventually die. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:55, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- As usual Bugs, you've hit the nail right on the head. I'm sure that the OP will be impressed by your insightful and erudite answer. Alansplodge (talk) 18:15, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- I do what I can. Next I expect the OP to ask why a raven is like a writing desk. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 22:53, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- As usual Bugs, you've hit the nail right on the head. I'm sure that the OP will be impressed by your insightful and erudite answer. Alansplodge (talk) 18:15, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Both insects and mollusks belong to Protostomia and Bilateria. However insects are in the Ecdysozoa superphyllum with mollusks in Lophotrochozoa. In terms of lifecycle they lay eggs, grow some kind of embryo, hatch, and mate. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 09:53, 17 August 2012 (UTC)

Loch Ness monster

What do scientists have to say about the Loch Ness Monster now, after this new photo? Bubba73 You talkin' to me? 03:13, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- "Wow, yet another meaningless, fuzzy photo". StuRat (talk) 03:59, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- And he saw it for 5-10 minutes - it would be nice to have a sequence of photos. Bubba73 You talkin' to me? 04:35, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Bearing in mind that "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence", I'd say we need a chunk of Nessie herself, for DNA testing, at the very least. I look forward to that day, if only because it will cause them to play one of my favorite songs by The Police again. StuRat (talk) 04:46, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- My award for the most incorrect maxim is the "Extraordinary claims..." one, closely followed by "What you can't see, can't hurt you. Those who are totally partisan about some notion will "require" massive evidence to the contrary to overturn their prejudices. Logically speaking, the amount and quality of evidence to refute (or corroborate) any theory should be the same, regardless of how loyal we are to the one held at the time. To say that one needs "extraordiany" evidence for much-favoured theories of long-standing is just another way of putting a tariff on their rivals. Myles325a (talk) 05:44, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Not following you at all. That a population of dinosaurs could exist in Loch Ness is an extraordinary claim. Fuzzy photos are not extraordinary evidence. A claim which is not extraordinary, like that there is a newly discovered species of purple fruit fly deep in the Amazon, wouldn't need such extraordinary evidence. A simple photo might be enough (although it would need to be clearer than those Nessie photos). StuRat (talk) 06:13, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- You have just restated your initial case, with no response to mine. My take is that in a formal way, labelling claims as "extraordinary" or "plausible" or "obvious" is to beg the question and alrady accord them a status that should be argued for, not applied at the outset. We should be just as satisfied / dissatisfied with evidence for a new species of fruitfly / dinosaurs in Lock Ness, and not expect the former to be "extraordinary" while the latter can just be "routine". That is the way entrenched theories retain their status, they are grandfathered in. This is an important point in the Philosophy of Empiricism, and is well-expounded by Karl Popper. the foremost philosopher of the Logic of Scientific Discovery. Myles325a (talk) 07:00, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- A better way to phrase the maxim would be to ask, what about the world as we know it would have to be different to make this endpoint seem more likely than any other? To have a dinosaur-like creature in a lake of that size would require quite a lot of jumps, mainly: 1. that this creature has survived for a long time without leaving significant evidence, despite all of the troublesome ecological things that would imply; 2. that somehow a breeding population of these creatures has survived long enough to significantly overlap with human occupation of the area, without leaving significant evidence. We contrast that with the steps that require these things to not exist: 1. human beings are superstitious, easily fooled, and/or have a variety of reasons for misleading one another. The latter narrative is easy to imagine — it requires no leaps whatsoever, since we have ample evidence of this sort of thing. The former narrative is hard to imagine: it would require quite a lot of unexpected junctures (unexpected in the sense that we don't have similar evidence). This isn't open and shut logic, but it does seem to suggest that if one is going to believe in the other narrative, and think it likely, then one would require fairly solid evidence in favor of it. "Extraordinary evidence" is just a reworking of Occam's Razor, and is as such just heuristic, but it is a useful heuristic. There are lots of things which, taken in isolation of the narratives that lead to them, sound fantastical. The notion that someone put an SUV-sized robot on Mars would be a completely fanciful, ridiculous idea, were there not a very well-documented chain of events leading up to it. (In any case, without wanting to appeal to authority, no philosophers of science think Popper's discussion of any of this is very adequate. It is popular mainly amongst people who do not understand it very well — which is to say, science popularizers or partisans — not philosophers, historians, or philosophically-minded scientists.) --Mr.98 (talk) 17:35, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- I agree with most of your comment but I wouldn't dismiss Popper so easily. I took an undergraduate unit in philosphy of science when I was doing my BSc and a large chunk of the curriculum was based on his work. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 23:17, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- He's an important figure to know, and was very influential, but once you get beyond the introduction to the philosophy of science, most of what remains is about how completely incorrect he was in articulating how science works in practice (no scientist acts like a Popperian actor, and most of them do exactly the opposite of what he says they should be doing) or even could work (even something as seemingly obvious as falsifiability becomes maddeningly difficult to reconcile with how actual practice would go down). There are probably a few rogue Popperians around but they are far more rare than the people who recognize that his stuff has big problems and doesn't really do what he thought it did. But this is a separate issue. --Mr.98 (talk) 00:46, 17 August 2012 (UTC)

- I agree with most of your comment but I wouldn't dismiss Popper so easily. I took an undergraduate unit in philosphy of science when I was doing my BSc and a large chunk of the curriculum was based on his work. 203.27.72.5 (talk) 23:17, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- A better way to phrase the maxim would be to ask, what about the world as we know it would have to be different to make this endpoint seem more likely than any other? To have a dinosaur-like creature in a lake of that size would require quite a lot of jumps, mainly: 1. that this creature has survived for a long time without leaving significant evidence, despite all of the troublesome ecological things that would imply; 2. that somehow a breeding population of these creatures has survived long enough to significantly overlap with human occupation of the area, without leaving significant evidence. We contrast that with the steps that require these things to not exist: 1. human beings are superstitious, easily fooled, and/or have a variety of reasons for misleading one another. The latter narrative is easy to imagine — it requires no leaps whatsoever, since we have ample evidence of this sort of thing. The former narrative is hard to imagine: it would require quite a lot of unexpected junctures (unexpected in the sense that we don't have similar evidence). This isn't open and shut logic, but it does seem to suggest that if one is going to believe in the other narrative, and think it likely, then one would require fairly solid evidence in favor of it. "Extraordinary evidence" is just a reworking of Occam's Razor, and is as such just heuristic, but it is a useful heuristic. There are lots of things which, taken in isolation of the narratives that lead to them, sound fantastical. The notion that someone put an SUV-sized robot on Mars would be a completely fanciful, ridiculous idea, were there not a very well-documented chain of events leading up to it. (In any case, without wanting to appeal to authority, no philosophers of science think Popper's discussion of any of this is very adequate. It is popular mainly amongst people who do not understand it very well — which is to say, science popularizers or partisans — not philosophers, historians, or philosophically-minded scientists.) --Mr.98 (talk) 17:35, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- In an ideal world, perhaps. In the real world, there are many people who would fake Nessie, just for a bit of publicity and/or business, but few who would fake the purple fruit fly in the Amazon, as it's existence is hardly going to boost the tourism industry there. If you require the same standard for both, then you will either end up accepting many hoaxes involving Nessie, Sasquatch, etc., as proof of their existence, and/or rejecting perfectly plausible evidence of lesser species.

- You have just restated your initial case, with no response to mine. My take is that in a formal way, labelling claims as "extraordinary" or "plausible" or "obvious" is to beg the question and alrady accord them a status that should be argued for, not applied at the outset. We should be just as satisfied / dissatisfied with evidence for a new species of fruitfly / dinosaurs in Lock Ness, and not expect the former to be "extraordinary" while the latter can just be "routine". That is the way entrenched theories retain their status, they are grandfathered in. This is an important point in the Philosophy of Empiricism, and is well-expounded by Karl Popper. the foremost philosopher of the Logic of Scientific Discovery. Myles325a (talk) 07:00, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- This reminds me of the similar problem in math (we have an article on it, but I forget the name). "If somebody hands you what he claims to be a fair coin, and you then toss heads 200 times in a row, what are the chances of it happening again, if you toss it another 200 times ?" Well, mathematically, the chances of the first 200 times being heads were 2200, or some 1.6×1060, and the odds of the second 200 tosses being heads would be the same. However, it's perfectly absurd, in the real world, to believe that it's a fair coin, after getting 200 heads in 200 tosses. Thus, once we reject this assertion, the probability of tossing another 200 heads in a row is far higher than the theoretical math would indicate. StuRat (talk) 07:55, 16 August 2012 (UTC)

- Popper's views about how science works are kind of outdated. You might be interested in the work of Thomas Kuhn. Consensus plays an important role in the functioning of science. If all hypotheses were given equal weight until disproved, nothing would ever get done. There are too many possible hypotheses, and not enough time to refute them all. Requiring stronger evidence to support large changes in current understanding is one of several tools for getting around this problem.--Srleffler (talk) 06:15, 18 August 2012 (UTC)