Slavs

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russians | 150 million[1][2][3][4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ukrainians | 39.8–57.5 million[5][6][7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Belarusians | 10 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rusyns | 200,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poles | 60 million[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Czechs | 11–12 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Slovaks | 6–6.5 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Silesians | 5 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moravians | 1 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kashubians | 300,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sorbs | 60,000–70,000[9][10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serbs | 10.5 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulgarians | 9.1–10.1 million[11][12][13] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Croats | 8–8.5 million[14][15] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bosniaks | 3 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Slovenes | 2.5 million[16] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Macedonians | 2–2.5 million[17] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Montenegrins | 500,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Slavic people are an Indo-European ethnic-linguistic group living in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, North Asia and Central Asia, who speak the Indo-European Slavic languages, and share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds. From the early 6th century they spread to inhabit most of Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans.[18] In addition to their main population centre in Europe, some East Slavs (Russians) also settled later in Siberia[19] and Central Asia.[20] Part of all Slavic ethnicities emigrated to other parts of the world.[21][22] Over half of Europe's territory is inhabited by Slavic-speaking communities.[23] The worldwide population of people of Slavic descent is close to 400 million for which they rank fourth among panethnicities in the world.

Modern nations and ethnic groups called by the ethnonym Slavs are considerably diverse both genetically and culturally, and relations between them – even within the individual ethnic groups themselves – are varied, ranging from a sense of connection to feelings of mutual hostility.[24]

Present-day Slavic people are classified into East Slavic (including Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians), West Slavic (including Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and Silesians),[25] and South Slavic (including Bulgarians, Macedonians, Slovenes, Croats, Bosniaks, Serbs and Montenegrins). For a more comprehensive list, see the ethnocultural subdivisions.

Ethnonym

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Slavic autonym is reconstructed in Proto-Slavic as Slověninъ. The oldest documents written in Old Church Slavonic and dating from the 9th century attest Словѣне Slověne to describe the Slavs. Other early Slavic attestations include Old East Slavic Словѣнѣ Slověně for "an East Slavic group near Novgorod." However, the earliest written references to the Slavs under this name are in other languages. In the 6th century AD Procopius, writing in Byzantine Greek, refers to the Σκλάβοι Sklaboi, Σκλαβηνοί Sklabēnoi, Σκλαυηνοί Sklauenoi, Σθλαβηνοί Sthlauenoi, or Σκλαβῖνοι Sklabinoi,[26] while his contemporary Jordanes refers to the Sclaveni in Latin.[27]

The Slavic autonym Slověninъ is usually considered a derivation from slovo "word," originally denoting "people who speak (the same language)," i.e. people who understand each other, in contrast to Slavic word denoting "foreign people" – němci, meaning "mumbling, murmuring people" (from Slavic němъ – "mumbling, mute"). The latter word may be the derivation of words to denote German/Germanic people in many later Slavic languages: e.g., Czech Němec, Slovak Nemec, Slovene Nemec, Belarusian, Russian and Bulgarian Немец, Serbian Немац, Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian Nijemac, Polish Niemiec, Ukrainian Німець, etc.[28], but another theory states that rather these words are derived from the name of the Nemetes tribe,[29][30] which is derived from the Celtic root nemeto-.[31][32]

The English word Slav is derived from the Middle English word sclave, which was borrowed from Medieval Latin sclavus "slave,"[33] itself a borrowing and Byzantine Greek σκλάβος sklábos "slave," which was in turn apparently derived from a misunderstanding of the Slavic autonym (denoting a speaker of their own languages). The Byzantine term Sklavinoi was loaned into Arabic as Saqaliba by medieval Arab historiographers.[citation needed] However, the origin of this word is disputed.[34][35]

Alternative proposals for the etymology of Slověninъ propounded by some scholars enjoy much less support. B.P. Lozinski argues that the word slava once had the meaning of worshipper, in this context meaning "practicer of a common Slavic religion," and from that evolved into an ethnonym.[36] S.B. Bernstein speculates that it derives from a reconstructed Proto-Indo-European *(s)lawos, cognate to Ancient Greek λαός laós "population, people," which itself has no commonly accepted etymology.[37] Meanwhile others have pointed out that the suffix -enin indicates a man from a certain place, which in this case should be a place called Slova or Slava, possibly a river name. The Old East Slavic Slavuta for the Dnieper River was argued by Henrich Bartek (1907–1986) to be derived from slova and also the origin of Slovene.[38]

History

Discourse on the early Slavs

The term Slav has different meanings depending upon the context in which it is used. This term refers to a culture (or cultures) living north of the Danube River, east of the Elbe River, and west of the Vistula River during the five hundred thirties CE.[39] In addition, Slav is an identifier for the common ethnic group.[40] Furthermore, Slav denotes any language with linguistic ties to the modern Slavic language family (which has no connection to a common culture or shared ethnicity).[41] Despite the various notions of Slav, it is unclear whether any of these descriptions add to an accurate representation of that group's history, since historians, such as George Vernadsky, Florin Curta, and Michael Karpovich have called into question how, why, and to what degree the Slavs were cohesive as a society between the sixth and ninth centuries CE.[42] When discussing the evidence that specialists use to construct a plausible history of the Slavs, the information tends to fall into three avenues of research: the archeological, the historiographic, and the linguistic.

Archaeologically, a myriad of physical evidence from that time period pertains to the Slavs. This evidence ranges from hill forts, to ceramic pots and fragments, to abodes. However, there are three major problems in studying the spread of early Slavic groups by purely archaeological methods. Archaeologists face difficulties in distinguishing which finds are truly Slavic and which are not.[43] In addition, many of these findings are either inaccurately carbon-dated or so isolated that they do not reflect organized Slavic settlement.[44] The combination of these facts makes it difficult to create a reliable chronology of ceramic materials, hill forts, houses, brooches, and other small artifacts. As a result, using archaeological finds without other forms of evidence is not wholly reliable for historical debates about this group.[45] The lack of grave sites also diminishes archaeologists' abilities to assess how the Slavs changed as a people, both in terms of their social behavior and their migratory patterns.[citation needed] Consequently, discerning where in northern Europe Slavic groups lived during the sixth to ninth centuries represents a challenge. The cumulative effects of these difficulties prevents the construction of a thorough history of Slavic development in Northern Europe during this period through archaeological evidence alone.[original research?]

Historiographically, a number of sources describe the Slavs. However, there are several problems using these texts to build upon the available knowledge of the early Slavs, even when used in a multidisciplinary fashion. The useful historical information about the Slavs from these texts is either cryptic or lacks any mention of their sources.[46] Moreover, these works tend to discuss the Slavs only in terms of their effects on surrounding empires, particularly the Byzantines and the Franks. The variety of names from historiographic texts that refer to the Slavs, such as the Antes, Sclaveni, and Venethi, in addition to the locales and regions which they at one point or another occupied, makes it laborious to establish a geographical boundary for major Slavic settlement. This is a troublesome task when the names of these places have not always remained the same or even survived. Most importantly, the majority of the texts utilized to describe the Slavs during this period are either second-hand accounts or describe an encounter with these groups years, decades, or centuries after it occurred. While earlier texts contextualize the Slavs' early history and later development, texts written about an event long after it had occurred make the relevant information less reliable. Unfortunately, neither earlier nor later texts directly aid understanding of the Slavs during the five hundreds to eight hundreds CE.

Linguistically, the pursuit of a Slavic history is also problematic. This pursuit has focused on three main areas of study: Slavic geographical names, names of flora and fauna, and "lexical and structural similarities and differences between Slavic and other languages.[47]" The use of ethnic identifiers in written texts during and after the 500s CE, such as the description of the Slavs as Antes, Sclaveni, and Venethi by their immediate neighbors, produces problems. Moreover, the concept of ethnicity during this period was so fluid that different ethnicities would be ascribed to the same group depending upon the situation of the encounter, such as in Michal Parczewski's map. This map, a conglomeration of different written fragments about the Slavs' homeland, selectively draws upon these fragments. In order to validate his preconceived theories about Slavic migration, Parczewski omitted information from his sources which directly contradicted his conclusions, thus making the map of Slavic settlement in relation to their neighbors during the sixth century CE extremely suspect.[48] Moreover, the association of particular styles of pots and burials with specific ethnonyms by archaeologists, and extremely selective use of historiographic materials, presumes a direct connection between language and ethnicity. These facts reinforce how subjective ethnic identification can be, especially in a region where many tribal groups existed and identified themselves as distinct from one another.[49]

The history of the early Slavs is inseparable from the political agenda behind much nineteenth and twentieth century archaeological, linguistic, and historiographic research. Florin Curta, an expert on the history of the early Slavs, contends that the process of creating such a history "was a function of both ethnic formation and ethnic identification".[50] However, this process became extremely blurred by a myriad of interests. These agendas ranged from Pan-Slavic researchers in Central and Eastern Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,[51] to post-World War Two European nations strengthening their newfound legitimacy,[52] to contemporary politicization of historical, archaeological, and linguistic discourse.[53]

Origins

Homeland debate

The location of the Slavic homeland has been the subject of significant debate. The Prague-Penkov-Kolochin complex of cultures of the 6th to 7th centuries CE are generally accepted to reflect the expansion of Slavic-speakers at that time.[54] Serious candidates for the core from which they expanded are cultures within the territories of modern Belarus, Poland, and Ukraine. The proposed frameworks are:

- Milograd culture hypothesis: The pre-Proto-Slavs (or Balto-Slavs) were the bearers of the Milograd culture (7th century BCE to 1st century CE) of northern Ukraine and southern Belarus.

- Chernoles culture hypothesis: The pre-Proto-Slavs were the bearers of the Chernoles culture (750–200 BCE) of northern Ukraine, and later the Zarubintsy culture (3rd century BCE to 1st century CE).

- Lusatian culture hypothesis: The pre-Proto-Slavs were present in north-eastern Central Europe since at least the late 2nd millennium BCE, and were the bearers of the Lusatian culture (1300–500 BCE), and later the Przeworsk culture (2nd century BCE to 4th century CE).

- Danube basin hypothesis: postulated by Oleg Trubachyov;[55] sustained at present by Florin Curta,[56] also supported by an early Medieval Slavic narrative source - Nestor's Chronicle

Research history

The starting point in the autochthonous/allochthonous debate was the year 1745, when Johann Christoph de Jordan published De Originibus Slavicis. The works of Slovak philologist and poet Pavel Jozef Šafárik (1795–1861) has influenced generations of scholars. The foundation of his theory was the work of Jordanes, Getica. Jordanes had equated the Sclavenes and the Antes to the Venethi (or Venedi) also known from much earlier sources, such as Pliny the Elder, Tacitus, and Ptolemy.

Pavel Jozef Šafárik bequeathed to posterity not only his vision of a Slavic history, but also a powerful methodology for exploring its Dark Ages: language.[56]

The Polish scholar Tadeusz Wojciechowski (1839–1919) was the first to use place names to write Slavic history. He was followed by A. L. Pogodin and the Polish botanist, J. Rostafinski.

The first to introduce archaeological data into the scholarly discourse about the early Slavs, Lubor Niederle (1865–1944), endorsed Rostafinski’s theory in his multi-volume work The Antiquities of the Slavs. Vykentyi V.Khvoika (1850–1914), a Ukrainian archaeologist of Czech origin, linked the Slavs with Neolithic Cucuteni culture. A. A. Spicyn (1858–1931) assigned to the Antes the finds of silver and bronze in central and southern Ukraine. Czech archaeologist Ivan Borkovsky (1897–1976) postulated the existence of a pottery "Prague type" which was a national, exclusively Slavic, pottery. Boris Rybakov, has issued a theory that made a link between both Spicyn’s "Antian antiquities" and the remains excavated by Khvoika from Chernyakhov culture and that those should be should be attributed to the Slavs.[56]

From the 19th century onwards, the debate became politically charged, particularly in connection with the history of the Partitions of Poland and German imperialism known as Drang nach Osten. The question whether Germanic or Slavic peoples were indigenous on the land east of the Oder river was used by factions to pursue their respective German and Polish political claims to governance of those lands.

Geneticists entered the debate in the 21st century. See the Genetics section below.

Earliest accounts

The relationship between the Slavs and a tribe called the Veneti east of the river Vistula in the Roman period is uncertain. The name may refer both to Balts and Slavs.

The Slavs under name of the Antes and the Sclaveni make their first appearance in Byzantine records in the early 6th century. Byzantine historiographers under Justinian I (527-565), such as Procopius of Caesarea, Jordanes and Theophylact Simocatta describe tribes of these names emerging from the area of the Carpathian Mountains, the lower Danube and the Black Sea, invading the Danubian provinces of the Eastern Empire.

Procopius wrote in 545 that "the Sclaveni and the Antae actually had a single name in the remote past; for they were both called Spori in olden times." He describes their social structure and beliefs:

For these nations, the Sclaveni and the Antae, are not ruled by one man, but they have lived from of old under a democracy, and consequently everything which involves their welfare, whether for good or for ill, is referred to the people. It is also true that in all other matters, practically speaking, these two barbarian peoples have had from ancient times the same institutions and customs. For they believe that one god, the maker of lightning, is alone lord of all things, and they sacrifice to him cattle and all other victims.

He mentions that they were tall and hardy:

"They live in pitiful hovels which they set up far apart from one another, but, as a general thing, every man is constantly changing his place of abode. When they enter battle, the majority of them go against their enemy on foot carrying little shields and javelins in their hands, but they never wear corselets. Indeed, some of them do not wear even a shirt or a cloak, but gathering their trews up as far as to their private parts they enter into battle with their opponents. And both the two peoples have also the same language, an utterly barbarous tongue. Nay further, they do not differ at all from one another in appearance. For they are all exceptionally tall and stalwart men, while their bodies and hair are neither very fair or blond, nor indeed do they incline entirely to the dark type, but they are all slightly ruddy in color. And they live a hard life, giving no heed to bodily comforts...".[57]

Jordanes tells us that the Sclaveni had swamps and forests for their cities.[58] Another 6th-century source refers to them living among nearly impenetrable forests, rivers, lakes, and marshes.[59]

Menander Protector mentions a Daurentius (577-579) that slew an Avar envoy of Khagan Bayan I. The Avars asked the Slavs to accept the suzerainty of the Avars, he however declined and is reported as saying: "Others do not conquer our land, we conquer theirs [...] so it shall always be for us".[60]

Scenarios of ethnogenesis

The Globular Amphora culture stretches from the middle Dniepr to the Elbe in the late 4th and early 3rd millennia BC. It has been suggested as the locus of a Germano-Balto-Slavic continuum (compare Germanic substrate hypothesis), but the identification of its bearers as Indo-Europeans is uncertain. The area of this culture contains numerous tumuli – typical for IE originators.

The Chernoles culture (8th to 3rd c. BC, sometimes associated with the "Scythian farmers" of Herodotus) is "sometimes portrayed as either a state in the development of the Slavic languages or at least some form of late Indo-European ancestral to the evolution of the Slavic stock."[61] The Milograd culture (700 BC - 100 AD), centered roughly on present-day Belarus, north of the contemporaneous Chernoles culture, has also been proposed as ancestral to either Slavs or Balts.

The ethnic composition of the bearers of the Przeworsk culture (2nd c. BC to 4th c. AD, associated with the Lugii) of central and southern Poland, northern Slovakia and Ukraine, including the Zarubintsy culture (2nd c. BC to 2nd c. AD, also connected with the Bastarnae tribe) and the Oksywie culture are other candidates.

The area of southern Ukraine is known to have been inhabited by Scythian and Sarmatian tribes prior to the foundation of the Gothic kingdom. Early Slavic stone stelae found in the middle Dniester region are markedly different from the Scythian and Sarmatian stelae found in the Crimea.

The (Gothic) Wielbark Culture displaced the eastern Oksywie part of the Przeworsk culture from the 1st century AD, some modern historians dispute the link between the Wielbark culture and the Goths. While the Chernyakhov culture (2nd to 5th c. AD, identified with the multi-ethnic kingdom established by the Goths) leads to the decline of the late Sarmatian culture in the 2nd to 4th centuries, the western part of the Przeworsk culture remains intact until the 4th century, and the Kiev culture flourishes during the same time, in the 2nd-5th c. AD. This latter culture is recognized as the direct predecessor of the Prague-Korchak and Pen'kovo cultures (6th-7th c. AD), the first archaeological cultures the bearers of which are indisputably identified as Slavic.

Proto-Slavic is thus likely to have reached its final stage in the Kiev area; there is, however, substantial disagreement in the scientific community over the identity of the Kiev culture's predecessors, with some scholars tracing it from the Ruthenian Milograd culture, others from the "Ukrainian" Chernoles and Zarubintsy cultures and still others from the "Polish" Przeworsk culture.

Genetics

The modern Slavic peoples carry a variety of Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups. Yet two paternal haplogroups predominate: R1a1a [M17] and I2a2a [L69.2=T/S163.2]. The frequency of Haplogroup R1a ranges from 63.39% in the Sorbs, through 56.4% in Poland, 54% in Ukraine, 52% in Russia, Belarus, to 15.2% in Republic of Macedonia, 14.7% in Bulgaria and 12.1% in Herzegovina.[62] The correlation between R1a1a [M17] and the speakers of Indo-European languages, particularly those of Eastern Europe (Russian) and Central and Southern Asia, was noticed in the late 1990s. From this Spencer Wells and colleagues, following the Kurgan hypothesis, deduced that R1a1a arose on the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[63]

Specific studies of Slavic genetics followed. In 2007 Rębała and colleagues studied several Slavic populations with the aim of localizing the Proto-Slavic homeland.[64] The significant findings of this study are that:

- Two genetically distant groups of Slavic populations were revealed: One encompassing all Western-Slavic, Eastern-Slavic, and few Southern-Slavic populations (north-western Croats and Slovenes), and one encompassing all remaining Southern Slavs. According to the authors most Slavic populations have similar Y chromosome pools — R1a. They speculate that this similarity can be traced to an origin in the middle Dnieper basin of Ukraine during the Late Glacial Maximum 15 kya.[65]

- However, some southern Slavic populations such as Bulgarians, Serbs, southern Croats and Macedonians are clearly separated from the tight DNA cluster of the rest of the Slavic populations. According to the authors this phenomenon is explained by "...contribution to the Y chromosomes of peoples who settled in the Balkan region before the Slavic expansion to the genetic heritage of Southern Slavs...."[65]

Marcin Woźniak and colleagues (2010) searched for specifically Slavic sub-group of R1a1a [M17]. Working with haplotypes, they found a pattern among Western Slavs which turned out to correspond to a newly-discovered marker, M458, which defines subclade R1a1a7. This marker correlates remarkably well with the distribution of Slavic-speakers today. The team, led by Peter Underhill, which discovered M458 did not consider the possibility that this was a Slavic marker, since they used the "evolutionary effective" mutation rate, which gave a date far too old to be Slavic. Woźniak and colleagues pointed out that the pedigree mutation rate, giving a later date, is more consistent with the archaeological record.[66]

Pomors are distinguished by the presence of Y Haplogroup N among them. Postulated to originate from southeast Asia, it is found at high rates in Uralic peoples. Its presence in Pomors (called "Northern Russians" in the report) attests to the non-Slavic tribes (mixing with Finnic tribes of northern Eurasia).[67]

On the other hand I2a1b1 (P41.2) is typical of the South Slavic populations, being highest in Bosnia-Herzegovina (>50%).[68] Haplogroup I2a2 is also commonly found in north-eastern Italians.[69] There is also a high concentration of I2a2a in north-east Romania, Moldova and western Ukraine. According to original studies, Hg I2a2 was believed to have arisen in the west Balkans sometime after the LGM, subsequently spreading from the Balkans through Central Russian Plain. Recently, Ken Nordtvedt has split I2a2 into two clades - N (northern) and S (southern), in relation where they arose compared to Danube river.[70] He proposes that N is slightly older than S. He recalculated the age of I2a2 to be ~ 2550 years and proposed that the current distribution is explained by a Slavic expansion from the area north-east of the Carpathians. There is a much lower level of I2a2a among Greeks and Albanians (including those in Kosovo and R. of Macedonia), which retain their non-Slavic languages, than in present-day majority South Slavic-speaking nations.

In 2008, biochemist Boris Abramovich Malyarchuk (Russian: Борис Абрамович Малярчук) et al. of the Institute of Biological Problems of the North, Russian Academy of Sciences, Magadan, Russia, used a sample (n=279) of Czech individuals to determine the frequency of "Mongoloid" "mtDNA lineages".[71] Malyarchuk found Czech mtDNA lineages were typical of "Slavic populations" with "1.8%" Mongoloid mtDNA lineage.[71] Malyarchuk added that "Slavic populations" "almost always" contain Mongoloid mtDNA lineage.[71] Malyarchuk said the Mongoloid component of Slavic people was partially added before the split of "Balto-Slavics" in 2,000-3,000 BCE with additional Mongoloid mixture occurring among Slavics in the last 4,000 years.[71] Malyarchuk said the "Russian population" was developed by the "assimilation of the indigenous pre-Slavic population of Eastern Europe by true Slavs" with additional "assimilation of Finno-Ugric populations" and "long-lasting" interactions with the populations of "Siberia" and "Central Asia".[71] Malyarchuk said that other Slavs "Mongoloid component" was increased during the waves of migration from "steppe populations (Huns, Avars, Bulgars and Mongols)", especially the decay of the "Avar Khaganate".[71]

Migrations

According to eastern homeland theory, prior to becoming known to the Roman world, Slavic speaking tribes were part of the many multi-ethnic confederacies of Eurasia - such as the Sarmatian, Hun and Gothic empires.[72] The Slavs emerged from obscurity when the westward movement of Germans in the 5th and 6th centuries AD (thought to be in conjunction with the movement of peoples from Siberia and Eastern Europe: Huns, and later Avars and Bulgars) started the great migration of the Slavs, who settled the lands abandoned by Germanic tribes fleeing the Huns and their allies: westward into the country between the Oder and the Elbe-Saale line; southward into Bohemia, Moravia, much of present day Austria, the Pannonian plain and the Balkans; and northward along the upper Dnieper river. Perhaps some Slavs migrated with the movement of the Vandals to Iberia and north Africa.[73]

Around the 6th century, Slavs appeared on Byzantine borders in great numbers.[74] The Byzantine records note that grass would not regrow in places where the Slavs had marched through, so great were their numbers. After a military movement even the Peloponnese and Asia Minor were reported to have Slavic settlements.[75] This southern movement has traditionally been seen as an invasive expansion.[76] By the end of the 6th century, Slavs had settled the Eastern Alps region.

Early Slavic states

When their migratory movements ended, there appeared among the Slavs the first rudiments of state organizations, each headed by a prince with a treasury and a defense force. Moreover, it was the beginnings of class differentiation, and nobles pledged allegiance either to the Frankish/ Holy Roman Emperors or the Byzantine Emperors.

In the 7th century, the Frankish merchant Samo, who supported the Slavs fighting their Avar rulers, became the ruler of the first known Slav state in Central Europe, which, however, most probably did not outlive its founder and ruler. This provided the foundation for subsequent Slavic states to arise on the former territory of this realm with Carantania being the oldest of them. Very old also are the Principality of Nitra and the Moravian principality (see under Great Moravia). In this period, there existed central Slavic groups and states such as the Balaton Principality, but the subsequent expansion of the Magyars, as well as the Germanisation of Austria, separated the northern and southern Slavs. The First Bulgarian Empire was founded in AD 681, the Slavic language Old Bulgarian became the main and official of the empire in AD 864. Bulgaria was instrumental in the spread of Slavic literacy and Christianity to the rest of the Slavic world.

Assimilation

Throughout their history, Slavs came into contact with non-Slavic groups. In the postulated homeland region (present-day Northern Ukraine), they had contacts with Sarmatians and the Germanic Goths. After their subsequent spread, they began assimilating non-Slavic peoples. For example, in the Balkans, there were Paleo-Balkan peoples, such as Illyrians, Greeks and romanized (North of the Jireček Line) or hellenized (South of the Jirecek-line) Thracians . Over time, due to the larger number of Slavs, the descendants most of the indigenous populations of the Balkans were Slavicized. The Thracians and Illyrians vanished from history during this period - although the modern Albanian nation claims to be the descendent of the Illyrian race. Exceptions are Greece, where the smaller number Slavs scattered there came to be Hellenized (aided in time by more Greeks returning to Greece in the 9th century and the role of the church and administration)[77] and Romania where Slavic people settled en route for present-day Greece, Republic of Macedonia, Bulgaria and East Thrace whereby the Slavic population had come to assimilate. Bulgars were also assimilated by local Slavs but their ruling status and subsequent land cast the nominal legacy of Bulgarian country and people onto all future generations. The Romance speakers within the fortified Dalmatian cities managed to retain their culture and language for a long time,[78] as Dalmatian Romance was spoken until the high Middle Ages. However, they too were eventually assimilated into the body of Slavs. In contrast, the Romano-Dacians in Wallachia managed to maintain their Latin-based language, despite much Slavic influence. After centuries of peaceful co-existence, the groups fused to form the Romanians.

In the western Balkans, south Slavs and Germanic Gepids intermarried with Avar invaders, eventually producing a Slavicised population. In central Europe, the Slavs intermixed with Germanic and Celtic, while the eastern Slavs encountered Uralic and Scandinavian peoples. Scandinavians (Varangians) and Finnic peoples were involved in the early formation of the Rus state but were completely Slavicised after a century. Some Finno-Ugric tribes in the north were also absorbed into the expanding Rus population.[67] At the time of the Magyar migration, the present-day Hungary was inhabited by Slavs, numbering about 200,000,[79] who were either assimilated or enslaved by the Magyars.[79] In the 11th and 12th centuries, constant incursions by nomadic Turkic tribes, such as the Kipchaks and the Pechenegs, caused a massive migration of East Slavic populations to the safer, heavily forested regions of the north.[80] In the Middle Ages, groups of Saxon ore miners settled in medieval Bosnia, Serbia and Bulgaria where they were Slavicised.

Polabian Slavs (Wends) settled in parts of England (Danelaw), apparently as Danish allies.[81] Polabian-Pomeranian Slavs are also known to have even settled on Norse age Iceland[citation needed]. Saqaliba refers to the Slavic mercenaries and slaves in the medieval Arab world in North Africa, Sicily and Al-Andalus. Saqaliba served as caliph's guards.[82][83] In the 12th century, there was intensification of Slavic piracy. The Wendish Crusade was started against the Polabian Slavs in 1147, as a part of the Northern Crusades. Niklot, pagan chief of the Slavic Obodrites, began his open resistance when Lothar III, Holy Roman Emperor, invaded Slavic lands. In August 1160 Niklot was killed and German colonization (Ostsiedlung) of the Elbe-Oder region began. In Hanoverian Wendland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lusatia invaders started germanization. Early forms of germanization were described by German monks: Helmold in the manuscript Chronicon Slavorum and Adam of Bremen in Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum.[84] The Polabian language survived until the beginning of the 19th century in what is now the German state of Lower Saxony.[85]

Cossacks, although Slavic-speaking and Orthodox Christians, came from a mix of ethnic backgrounds, including Tatars and other Turks. Many early members of the Terek Cossacks were Ossetians.

The Gorals of southern Poland and northern Slovakia are partially descended from Romance-speaking Vlachs who migrated into the region from the 14th to 17th centuries and were absorbed into the local population. The population of Moravian Wallachia also descend of this population.

Conversely, some Slavs were assimilated into other populations. Although the majority continued south, attracted by the riches of the territory which would become Bulgaria, a few remained in the Carpathian basin and were ultimately assimilated into the Magyar or Romanian population. There is a large number of river names and other placenames of Slavic origin in Romania.[86] Similarly, the populations of the respective eastern parts of Austria and Germany are to some degree made up of people with Slavic ancestry.

Modern history

As of 1878, there were only three free Slavic states in the world: Russian Empire, Serbia and Montenegro. Bulgaria was also free but was de jure vassal to the Ottoman Empire until official independence was declared in 1908. In the entire Austro-Hungarian Empire of approximately 50 million people, about 23 million were Slavs. The Slavic peoples who were, for the most part, denied a voice in the affairs of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, were calling for national self-determination. During World War I, representatives of the Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes set up organizations in the Allied countries to gain sympathy and recognition.[87] In 1918, after World War I ended, the Slavs established such independent states as Czechoslovakia, the Second Polish Republic, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

One of Hitler's ambitions at the start of World War II was to exterminate, expel, or enslave most or all East and West Slavs from their native lands and to kill 30 million Slavic people, so as to make living space for German settlers. This plan of genocide[88] was to be carried into effect gradually over 25 to 30 years.

Because of the vastness and diversity of the territory occupied by Slavic people, there were several centers of Slavic consolidation. In the 19th century, Pan-Slavism developed as a movement among intellectuals, scholars, and poets, but it rarely influenced practical politics and did not find support in some nations that had Slavic origins. Pan-Slavism became compromised when the Russian Empire started to use it as an ideology justifying its territorial conquests in Central Europe as well as subjugation of other ethnic groups of Slavic origins such as Poles and Ukrainians, and the ideology became associated with Russian imperialism. The common Slavic experience of communism combined with the repeated usage of the ideology by Soviet propaganda after World War II within the Eastern bloc (Warsaw Pact) was a forced high-level political and economic hegemony of the USSR dominated by Russians. A notable political union of the 20th century that covered most South Slavs was Yugoslavia, but it ultimately broke apart in the 1990s along with the Soviet Union.

The word "Slavs" was used in the national anthem of the Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Yugoslavia (1943–1992) and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992–2003), later Serbia and Montenegro (2003–2006).

Former Soviet states such as Kazakhstan, have very large minority Slavic populations with most being Russians. Also former satellite states and Warsaw Pact territories also have large minority Slavic populations also being Russian or Ukrainian and those from the three Slavic states in the Soviet Union. As of now, Kazakhstan have the largest Slavic minority population, with all if not most, being Russians.

Population

The worldwide population of people of Slavic descent is close to 400 million. The three largest Slavic ethnic groups are Russians (150 million), Poles (60 million), and Ukrainians (50 million). Other Slavic ethnic groups include Czechs (11 million), Serbs (10,5 million), Bulgarians (10 million), Belarusians (10 million), Croats (8 million), Slovaks (7 million), Silesians (5 million), Bosniaks (3 million), Macedonians (3 million), Slovenes (2,5 million), Montenegrins (700 000). Polish and Serbians make up the largest Slavic populations or Slavic-descended American population in the United States.

Religion

Most Slavic populations gradually adopted Christianity (the East Slavs Orthodox Christianity and the West Slavs Roman Catholicism, with South Slavs split by the two religions) between 6th and 10th century, and consequently their old pagan beliefs declined. See also Rodnovery.

The majority of contemporary Slavs who profess a religion are Orthodox, followed by Roman Catholic. A very small minority are Protestant. Bosniaks, Gorani, Torbeshi and Pomaks are Muslims. Religious delineations by nationality can be very sharp; usually in the Slavic ethnic groups the vast majority of religious people share the same religion. Some Slavs are atheist or agnostic: only 19% of Czechs professed belief in god/s in the 2005 Eurobarometer survey, making them one of the most irreligious people in the world.

The main Slavic ethnic groups by religion: Template:Multicol Mainly Orthodox Christians

Template:Multicol Mainly Roman Catholic:

Template:Multicol-end Template:Multicol Mainly Muslim:

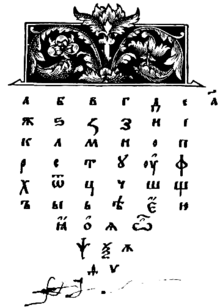

Alphabet

The alphabet depends on what religion is usual for the respective Slavic ethnic groups. The Orthodox use the Cyrillic alphabet and the Roman Catholics use Latin alphabet, the Bosniaks which are Muslims also use the Latin. Few Greek Roman and Roman Catholics use the Cyrillic alphabet however. The Serbian language and Montenegrin language can be written using both the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets, but the Cyrillic remains preferred by a large majority. There is also a Latin script to write in Belarusian, called the Lacinka alphabet.

Language

Slavic studies began as an almost exclusively linguistic and philological enterprise. As early as 1833, Slavic languages were recognized as Indo-European.[56]

Slavic standard languages which are official in at least one country:

- Belarusian

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Croatian

- Czech

- Macedonian

- Montenegrin

- Polish

- Russian

- Serbian

- Silesian

- Slovak

- Slovene

- Ukrainian

Proto-Slavic language

Proto-Slavic, the ancestor language of all Slavic languages, is a descendant of common Proto-Indo-European, via a Balto-Slavic stage in which it developed numerous lexical and morphophonological isoglosses with Baltic languages. In the framework of the Kurgan hypothesis, "the Indo-Europeans who remained after the migrations [from the steppe] became speakers of Balto-Slavic".[89]

Proto-Slavic, sometimes referred to as Common Slavic or Late Proto-Slavic, is defined as the last stage of the language preceding the geographical split of the historical Slavic languages. That language was uniform, and on the basis of borrowings from foreign languages and Slavic borrowings into other languages, cannot be said to have any recognizable dialects, suggesting a comparatively compact homeland.[90] Slavic linguistic unity was to some extent visible as late as Old Church Slavonic manuscripts which, though based on local Slavic speech of Thessaloniki in Macedonia, could still serve the purpose of the first common Slavic literary language.[91]

Ethnocultural subdivisions

Slavs are customarily divided along geographical lines into three major subgroups: East Slavs, West Slavs, and South Slavs, each with a different and a diverse background based on unique history, religion and culture of particular Slavic group within them. The East Slavs may all be traced to Slavic-speaking populations that were loosely organized under the Kievan Rus' empire beginning in the 10th century AD.

Almost all of the South Slavs can be traced to ethnic Slavs who mixed with the local European population of the Balkans (Illyrians, Dacians/Thracians, Greeks; the early South Slavs also mixed with Asiatic inviders as Huns, Avars, Bulgars etc. They were particularly influenced by the Orthodox Church, although Roman Catholicism and Latin influences were more pertinent in Dalmatia. The West Slavs and the Croats and Slovenes do not share either of these backgrounds, as they expanded to the West and integrated into the cultural sphere of Western (Roman Catholic) Christianity around this time also mixing with nearby Germanic tribes.

In addition there has been a tendency to consider the category of Northern Slavs. Presently this category is considered to be of East and West Slavs, in opposition to South Slavs, however in 19th century opinions about individual languages/ethnicities varied.

East Slavs

West Slavs

Czech-Slovak group

Lechitic group

- Obodrites/Abodrites

South Slavs

Eastern group

- Gorani (recognized ethnicity)

Template:Multicol-break Template:Multicol-end

Western group

- Croats

- Bunjevci (subgroup of Croats)

- Janjevci (Croats in Kosovo)

- Burgenland Croats (in Austria)

- Molise Croats (in eastern Italy)

- Krashovans (Croats in Romania)

- Šokci (subgroup of Croats)

- Bosniaks (Croats in Hungary) (Croats in Hungary)

- Moravian Croats (Croats in the Czech Republic)

- Muslims by nationality12 (recognized ethnicity)

Notes to list of ethnocultural divisions

^e Extinct

^1 Also considered part of Rusyns

^2 Considered transitional between Ukrainians and Belarusians

^3 Also considered part of Ukrainians

^4 The ethnic affiliation of the Lemkos has become an ideological conflict. It has been alleged that among the Lemkos the idea of "Carpatho-Ruthenian" nation is supported only by Lemkos residing in Transcarpathia and abroad[92]

^5 Also considered part of Poles

^6 Also sometimes considered part of Poles and Czechs (controversial)

^7 Most Shopi self-declare as Bulgarians, but others declare as Macedonians or Serbs. Their dialect is transitional between west and east South Slavic group. Cognate with Torlaks.

^8 Most Torlaks self-declare as Serbs. Cognate with Shopi.

^9 Silingi is also Silesian tribe, but this Germanic tribe.

^10 Both occur widely in northeastern Croatia and also in northern Serbia; their Ikavian accent is subequal[clarification needed] as southern Croats in Hercegovina and Dalmatian mainland from where they once emigrated. Considered part of Croats by most of them, although recently (since Yugoslav disaster) some within Serbia consider themselves a separate peoples

^11 These Gorani are a Slavic nation living mainly in Kosovo, Macedonia and Albania; not to be confound with other Gorani (or Gorinci) in the highlands of western Croatia (Gorski Kotar county).

^12 A census category recognized as an ethnic group. Most Slavic Muslims (especially in Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia) now opt for Bosniak ethnicity, but some still use the "Muslim" designation. Bosniak and Muslim are considered two ethnonyms for a single ethnicity and the terms may even be used interchangeably. However, a small number of people within Bosnia and Herzegovina declare Bosniak but are not necessarily Muslim by faith.

^13 This identity continues to be used by a minority throughout the former Yugoslav republics. The nationality is also declared by diasporans living in the USA and Canada. There are a multitude of reasons as to why people prefer this affiliation, some published on the article.

^14 Generally, heavily mixed with German people

^15 Most inhabitants of historic Moravia considered themselves as Czechs but significant amount declared their Moravian nationality, different from that Czech (although people from Bohemia proper and Moravia speak the same language).

^16 Not to be confused with Silesians from Poland. Unlike them, Silesians in Czechia speak Czech.

Note: Besides ethnic groups, Slavs often identify themselves with the local geographical region in which they live. Some of the major regional South Slavic groups include: Zagorci in northern Croatia, Istrijani in westernmost Croatia, Dalmatinci in southern Croatia, Boduli in Adriatic islands, Vlaji in hinterland of Dalmatia, Slavonci in eastern Croatia, Bosanci in Bosnia, Hercegovci in southern Bosnia (Herzegovina), Krajišnici in western Bosnia, Semberci in northeast Bosnia, Srbijanci in Serbia proper, Šumadinci in central Serbia, Vojvođani in northern Serbia, Sremci in Syrmia, Bačvani in northwest Vojvodina, Banaćani in Banat, Sandžaklije (Muslims in Serbia/Montenegro border), Kosovci in Kosovo, Crnogorci in Montenegro proper, Bokelji in southwest Montenegro, Trakiytsi in Upper Thracian Lowlands, Dobrudzhantsi in north-east Bulgarian region, Balkandzhii in Central Balkan Mountains, Miziytsi in north Bulgarian region, Warmiaks and Masurians in north-east Polish regions Warmia and Mazuria, Pirintsi[93] in Blagoevgrad Province, Ruptsi in the Rhodopes etc.

Another interesting note is that the very term Slavic itself was registered in the US census of 2000 by more than 127,000 residents.

See also

Notes

- ^ http://www.russkie.org/index.php?module=fullitem&id=4194

- ^ http://www.rusichi-center.ru/e/2663163-chechentsyi-trebuyut-snesti-pamyatnik-yuriyu-budano

- ^ http://rcultura.ucoz.ru/index/russkie/0-10

- ^ http://www.russedina.ru/articul.php?aid=2354&pid=5

- ^ Ukrainians at the Joshua Project

- ^ The Ukrainian World Congress states that the Ukrainian diaspora makes 20 million: 20mln Ukrainians living abroad

- ^ UWC continually and diligently defends the interests of over 20 million Ukrainians...

- ^ Świat Polonii, witryna Stowarzyszenia Wspólnota Polska: "Polacy za granicą" (Polish people abroad as per summary by Świat Polonii, internet portal of the Polish Association Wspólnota Polska)

- ^ "Germany's Sorb Minority Fights to Save Villages From Vattenfall". Bloomberg. 18 December 2007.

- ^ http://www.faqs.org/minorities/Eastern-Europe/Sorbs-of-East-Germany.html

- ^

Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) (1986–2009). "Bulgarian". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. SIL International. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^

"Chairman of Bulgaria's State Agency for Bulgarians Abroad - 3-4 million Bulgarians abroad in 2009 [[:Template:Bg icon]]". 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^

"Bulgarian Minister without Portfolio - 4 million Bulgarians outside Bulgaria in 2010 [[:Template:Bg icon]]". 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Daphne Winland (2004), "Croatian Diaspora", in Melvin Ember, Carol R. Ember, Ian Skoggard (ed.), Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities, vol. 2 (illustrated ed.), Springer, p. 76, ISBN 0-306-48321-1, 9780306483219,

It is estimated that 4.5 million Croatians live outside Croatia (...)

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Hrvatski Svjetski Kongres, Croatian World Congress, "4.5 million Croats and people of Croatian heritage live outside of the Republic of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina", also quoted here

- ^ Zupančič, Jernej (2004). "Ethnic Structure of Slovenia and Slovenes in Neighbouring Countries" (PDF). Slovenia: a geographical overview. Association of the Geographic Societies of Slovenia. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nasevski, Boško (1995). Македонски Иселенички Алманах '95. Skopje: Матица на Иселениците на Македонија. pp. 52 & 53.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Geography and ethnic geography of the Balkans to 1500

- ^ Fiona Hill, Russia — Coming In From the Cold?, The Globalist, 23 February 2004

- ^ Robert Greenall, Russians left behind in Central Asia, BBC News, 23 November 2005

- ^ Terry Kirby, 750,000 and rising: how Polish workers have built a home in Britain, The Independent, 11 February 2006.

- ^ Poles in the United States, Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ Barford 2001: 1

- ^ Bideleux 1998

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (18 September 2006). "Slav (people) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ Procopius, History of the Wars,\, VII. 14. 22-30, VIII.40.5

- ^ Jordanes, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, V.33.

- ^ Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe (2000), p. 193.

- ^ The Journal of Indo-European studies 1974, v.2

- ^ Etymology of the Polish-language word for Germany Template:Pl icon

- ^ Xavier Delamarre (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise. Éditions Errance, p. 233.

- ^ John T. Koch (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, p. 1351.

- ^ Slav, on Oxford Dictionaries

- ^ F. Kluge, Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. 2002, siehe «Sklave»

- ^ Ф. М. Достоевский. Полное собрание сочинений: в 30-ти т. Т. 23. М., 1990, с. 63, 382.

- ^ Lozinski B.P., The Name SLAV, Essays in Russian History, Archon Books, 1964.

- ^ Bernstein 1961

- ^ Etudes slaves et est-européennes: Slavic and East-European studies, Volume 3 (1958), p.107.

- ^ Florin Curta, The Making of The Slavs: History and Archaeology of The Lower Danube Region, ca. 500-700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 335-37

- ^ Curta, The Making of The Slavs, 6-35

- ^ Paul M. Barford, 2004. Identity And Material Culture Did The Early Slavs Follow The Rules Or Did They Make Up Their Own? East Central Europe 31, no. 1:102-103

- ^ Curta, The Making of The Slavs, Curta, Florin. 2001. Pots, Slavs and 'Imagined Communities': Slavic Archaeologies And The History of The Early Slavs. European Journal of Archaeology 4, no. 3:367-384, George Verdansky and Michael Karpovich, Ancient Russia, vol. 1 of History of Russia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1943)

- ^ Sebastian Brather. 2004. The Archaeology of the Northwestern Slavs (Seventh To Ninth Centuries). East Central Europe 31, no. 1:78-81.

- ^ Brather, The Archaeology of the Northwestern Slavs, 79

- ^ Barford, Identity And Material Culture, 106

- ^ Curta, The Making of The Slavs, 36-38

- ^ Barford, Identity And Material Culture, 103

- ^ Barford, Identity And Material Culture, 104-5

- ^ Barford, Identity And Material Culture, 105-6, Curta, The Making of The Slavs, 84-87

- ^ Curta, The Making of The Slavs, 335

- ^ Barford, Identity And Material Culture, 99

- ^ Barford, Identity And Material Culture, 99-101, Curta, The Making of The Slavs, 358-375, Florin Curta. 2001. Pots, Slavs and 'Imagined Communities': Slavic Archaeologies And The History of The Early Slavs. European Journal of Archaeology 4, no. 3:370, Pavel M. Dolukhanov, The Early Slavs (New York: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996), 7

- ^ Barford, Identity And Material Culture, 100, 102

- ^ Peter Heather, Empires and Barbarians: Migration, development and the birth of Europe (2009), pp. 389-396.

- ^ Trubačev 1985

- ^ a b c d Florin Curta, The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500-700 (Cambridge University Press)

- ^ Procopius, History of the Wars, VII. 14. 22-30.

- ^ Jordanes, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, V. 35.

- ^ Maurice's Strategikon: handbook of Byzantine military strategy, trans. G.T. Dennis (1984), p. 120.

- ^ Curta (2001), pp. 91–92, 315.

- ^ James P. Mallory, "Chernoles Culture", EIEC

- ^ Peričić et al. 2005.

- ^ Wells et al., The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 98, no. 18 (2001), pp. 10244-10249; the connection between Y-DNA R-M17 and the spread of Indo-European languages was first proposed by T. Zerjal et al., "The use of Y-chromosomal DNA variation to investigate population history: recent male spread in Asia and Europe," in S.S. Papiha, R. Deka and R. Chakraborty (eds.), Genomic Diversity: applications in human population genetics (1999), pp. 91–101.

- ^ Rębała et al. 2007.

- ^ a b Rębała et al. 2007: 408

- ^ M. Woźniak et al., "Similarities and distinctions in Y Chromosome gene pool of Western Slavs," American Journal of Physical Anthropology, vol. 142, no. 4 (2010), pp. 540-548.

- ^ a b Balanovsky et al. 2008

- ^ Pericic et al., "High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations," MBE.oxfordjournals.org

- ^ Vincenza Battaglia et al., "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe," European Journal of Human Genetics advance online publication 24 December 2008; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249.

- ^ Family Tree DNA, Y-Haplogroup I2a Project - Results

- ^ a b c d e f Malyarchuk, B.A., M. A. Perkova, & Derenko, M.V. (2008). On the Origin of Mongoloid Component in the Mitochondrial Gene Pool of Slavs. Russian Journal of Genetics, 44(3), pp. 344–349. ISSN 1022-7954.

- ^ Velentin Sedov: Slavs in Middle Ages

- ^ Mallory & Adams "Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture

- ^ Mango 1980

- ^ Tachiaos 2001

- ^ Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou 1992: Middle Ages

- ^ Fine, J.V.A. The Early Medieval Balkans, page 41. University of Michigan Press, 1983, 336 pages.

- ^ Fine, J.V.A. The Early Medieval Balkans, page 35. University of Michigan Press, 1983, 336 pages.

- ^ a b A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ Klyuchevsky, Vasily (1987). The course of the Russian history. v.1: "Myslʹ. ISBN 5-244-00072-1. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Shore, Thomas William (2008). Origin of the Anglo-Saxon Race - A Study of the Settlement of England and the Tribal Origin of the Old English People. READ BOOKS. pp. 84–102. ISBN 1-4086-3769-3.

- ^ Lewis 1994: ch. 1

- ^ Eigeland 1976

- ^ Wend – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Polabian language

- ^ Alexandru Xenopol, Istoria românilor din Dacia Traiană, 1888, vol. I, p. 540

- ^ Austria-Hungary

- ^ Eichholtz 2004

- ^ F. Kortlandt, The spread of the Indo-Europeans, Journal of Indo-European Studies, vol. 18 (1990), pp. 131-140. Online version, p.4.

- ^ F. Kortlandt, The spread of the Indo-Europeans, Journal of Indo-European Studies, vol. 18 (1990), pp. 131-140. Online version, p.3.

- ^ J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (2006), pp. 25-26.

- ^ Who are we, lemko.org

- ^ Buchanan 2006: 11

References

- Balanovsky, Oleg, et al.. 2008. Two Sources of the Russian Patrilineal Heritage in Their Eurasian Context. American Journal of Human Genetics, 10 January 2008, 82(1): 236-250.

- Barford, P. M. 2001. The Early Slavs. Culture and Society in Early Medieval Europe. Cornell University Press. 2001. ISBN 0-901439-77-9.

- Bernstein, S. B. 1961. Очерк сравнительной грамматики славянских языков, vol. 1-2. Moscow.

- Bideleux, Robert. 1998. History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge.

- Buchanan, Donna Anne. 2006. Performing Democracy: Bulgarian Music and Musicians in Transition. (Google Books preview.) Univ. of Chicago Press. Series: Chicago studies in ethnomusicology. ISBN 0-226-07826-4

- Český statistický úřad (Czech Statistical Office). 2006. Obyvatelstvo hlásící se k jednotlivým církvím a náboženským společnostem.

- Eichholtz, Dietrich. 2004. »Generalplan Ost« zur Versklavung osteuropäischer Völker. UTOPIE kreativ, September 2004, 167: 800-808.

- Eigeland, Tor. 1976. The golden caliphate. Saudi Aramco World, September/October 1976, pp. 12–16.

- Lacey, Robert. 2003. Great Tales from English History. Little, Brown and Company. New York. 2004. ISBN 0-316-10910-X.

- Lewis, Bernard. Race and Slavery in the Middle East. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Mango, Cyril. 1980. Cyril Mango. Byzantium: The Empire of New Rome. Scribner's.

- Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou, Maria. 1992. The "Macedonian Question": A Historical Review. © Association Internationale d'Etudes du Sud-Est Europeen (AIESEE, International Association of Southeast European Studies), Comité Grec. Corfu: Ionian University. (English translation of a 1988 work written in Greek.)

- Peričić, Marijana, et al.. 2005. High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2005 22(10): 1964-1975; doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185.

- Rębała, Krzysztof, et al.. 2007. Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin. Journal of Human Genetics, May 2007, 52(5): 408-414.

- Religare.ru. 2007. Опубликована подробная сравнительная статистика религиозности в России и Польше. 6 June 2007.

- Semino, Ornella, et al.. 2000. The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: a Y Chromosome Perspective. (Abstract.) Science, 10 November 2000, 290: 1155-1159.

- Tachiaos, Anthony-Emil N. 2001. Cyril and Methodius of Thessalonica: The Acculturation of the Slavs. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Trubačev, O. N. 1985. Linguistics and Ethnogenesis of the Slavs: The Ancient Slavs as Evidenced by Etymology and Onomastics. Journal of Indo-European Studies (JIES), 13: 203-256.

Further reading

- P.M. Barford, The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe, British Museum Press, London 2001, ISBN 978-0-7141-2804-7

- F. Curta, The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-521-80202-4.

- P. Vlasto, The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom, An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1970, ISBN 978-0-521-07459-9, ISBN 978-0-521-10758-7

External links

- The Slavic Ethnogenesis, Identifying the Slavic Stock and Origins of the Slavs

- Some problems of the ethnogenesis of the Slavs and of the settlement process of the Central Danubian Slovenes – Slovaks in the 6th and 7th century

- The Ancient Slavs ancientmilitary.com

- The expansion of The Slavs, Third Millenium Library

- Lozinski, B. Philip (1964, 2004). Ferguson, Alan D.; Levin, Alfred (eds.). "Essays in Russian History, A collection dedicated to George Vernadsky". Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, Vassil Karloukovski: 19–30.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help). - Kortlandt, Frederik. "From Proto-Indo-European to Slavic" (PDF). Frederik Kortlandt. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- The origin of the Baltic, Germand and Slavic people. The Iceland ages.

- "Najstariji period istorije Slovena (Venedi, Sloveni i Anti)" - N. S. Deržavin

- Sloveni: Unde orti estis? Slováci, KDE sú vaše korene? , by Cyril A. Hromník (mainly in Slova).

- Site about Slavics, Slavic Countries, Cultures, Languages, etc (mainly in Russian)

- The early wars between the Macedonian Slavs and the Byzantines (from medieval sources)

- Halecki, Oscar. "Borderlands of Western Civilization, a History of East Central Europe" (PDF). Oscar Halecki. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective"

- Mitochondrial DNA Phylogeny in Eastern and Western Slavs, B. Malyarchuk, T. Grzybowski, M. Derenko, M. Perkova, T. Vanecek, J. Lazur, P. Gomolcaknd I. Tsybovsky, Oxford Journals

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Slavs". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Leopold Lénard (1913). "The Slavs". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.