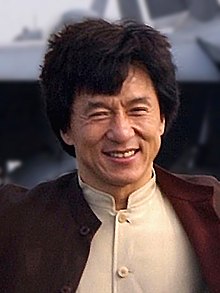

Jackie Chan

Template:Chinese name Template:Infobox Chinese-language singer and actor Template:Contains Chinese text Chan Kong-sang, SBS, MBE,[1] PMW,[2] (陳港生; born 7 April 1954),[3] known professionally as Jackie Chan, is a Hong Kong martial artist, actor, film director, producer, stuntman, and singer. In his movies, he is known for his acrobatic fighting style, comic timing, use of improvised weapons, and innovative stunts, which he typically performs himself. Chan has been training in Kung fu and Wing Chun. He has been acting since the 1960s and has appeared in over 150 films.

Chan has received stars on the Hong Kong Avenue of Stars and the Hollywood Walk of Fame. As a cultural icon, Chan has been referenced in various pop songs, cartoons, and video games. An operatically trained vocalist, Chan is also a Cantopop and Mandopop star, having released a number of albums and sung many of the theme songs for the films in which he has starred. He is also a notable philanthropist.[4] In 2015, Forbes magazine estimated his net worth to be $350 million.[5]

Early life

Chan was born on 7 April 1954, in British Hong Kong, as Chan Kong-sang, to Charles and Lee-Lee Chan, refugees from the Chinese Civil War. His mother or parents nicknamed him Pao-pao Chinese: 炮炮 ("Cannonball") because the energetic child was always rolling around.[6] His parents worked for the French ambassador in Hong Kong, and Chan spent his formative years within the grounds of the consul's residence in the Victoria Peak district.[7]

Chan attended the Nah-Hwa Primary School on Hong Kong Island, where he failed his first year, after which his parents withdrew him from the school. In 1960, his father emigrated to Canberra, Australia, to work as the head cook for the American embassy, and Chan was sent to the China Drama Academy, a Peking Opera School run by Master Yu Jim-yuen.[7][8] Chan trained rigorously for the next decade, excelling in martial arts and acrobatics.[9] He eventually became part of the Seven Little Fortunes, a performance group made up of the school's best students, gaining the stage name Yuen Lo in homage to his master. Chan became close friends with fellow group members Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao, and the three of them later became known as the Three Brothers or Three Dragons.[10] After entering the film industry, Chan along with Sammo Hung got the opportunity to train in hapkido under the grand master Jin Pal Kim, and Chan eventually attained a black belt.[11] Jackie Chan also trained in other styles of martial arts such as karate, judo, taekwondo, and Jeet Kune Do.

He began his career by appearing in small roles at the age of five as a child actor. At age eight, he appeared with some of his fellow "Little Fortunes" in the film Big and Little Wong Tin Bar (1962) with Li Li-Hua playing his mother. Chan appeared with Li again the following year, in The Love Eterne (1963) and had a small role in King Hu's 1966 film Come Drink with Me.[12] In 1971, after an appearance as an extra in another kung fu film, A Touch of Zen, Chan was signed to Chu Mu's Great Earth Film Company.[13] At seventeen, he worked as a stuntman in the Bruce Lee films Fist of Fury and Enter the Dragon under the stage name Chan Yuen Lung (Chinese: 陳元龍).[14] He received his first starring role later that year in Little Tiger of Canton that had a limited release in Hong Kong in 1973.[15] In 1975, due to the commercial failures of his early ventures into films and trouble finding stunt work, Chan starred in a comedic adult film All in the Family in which Chan appears in his first nude sex scene. It is the only film he has made to date without a single fight scene or stunt sequence.[16] Jackie Chan later also appeared in one other sex scene, in Shinjuku Incident.

Chan joined his parents in Canberra in 1976, where he briefly attended Dickson College and worked as a construction worker.[17] A fellow builder named Jack took Chan under his wing, thus earning Chan the nickname of "Little Jack" that was later shortened to "Jackie", and the name Jackie Chan has stuck with him ever since.[18] In the late 1990s, Chan changed his Chinese name to Fong Si-lung (Chinese: 房仕龍), since his father's original surname was Fong.[18]

Film career

Early exploits: 1976–1979

In 1976, Jackie Chan received a telegram from Willie Chan, a film producer in the Hong Kong film industry who had been impressed with Jackie's stunt work. Willie Chan offered him an acting role in a film directed by Lo Wei. Lo had seen Chan's performance in the John Woo film Hand of Death (1976) and planned to model him after Bruce Lee with the film New Fist of Fury.[13] His stage name was changed to Sing Lung (Chinese: 成龍, also transcribed as Cheng Long,[19] literally "become the dragon") to emphasise his similarity to Bruce Lee, whose stage name meant "Little Dragon" in Chinese. The film was unsuccessful because Chan was not accustomed to Lee's martial arts style. Despite the film's failure, Lo Wei continued producing films with similar themes, but with little improvement at the box office.[20]

Chan's first major breakthrough was the 1978 film Snake in the Eagle's Shadow, shot while he was loaned to Seasonal Film Corporation under a two-picture deal.[21] Director Yuen Woo-ping allowed Chan complete freedom over his stunt work. The film established the comedic kung fu genre, and proved refreshing to the Hong Kong audience.[22] Chan then starred in Drunken Master, which finally propelled him to mainstream success.[23]

Upon Chan's return to Lo Wei's studio, Lo tried to replicate the comedic approach of Drunken Master, producing Half a Loaf of Kung Fu and Spiritual Kung Fu.[18] He also gave Chan the opportunity to co-direct The Fearless Hyena with Kenneth Tsang. When Willie Chan left the company, he advised Jackie to decide for himself whether or not to stay with Lo Wei. During the shooting of Fearless Hyena Part II, Chan broke his contract and joined Golden Harvest, prompting Lo to blackmail Chan with triads, blaming Willie for his star's departure. The dispute was resolved with the help of fellow actor and director Jimmy Wang Yu, allowing Chan to stay with Golden Harvest.[21]

Success in the action comedy genre: 1980–1987

Willie Chan became Jackie's personal manager and firm friend, and has remained so for over 30 years. He was instrumental in launching Chan's international career, beginning with his first forays into the American film industry in the 1980s. His first Hollywood film was The Big Brawl in 1980.[24] Chan then played a minor role in the 1981 film The Cannonball Run, which grossed $100 million worldwide. Despite being largely ignored by audiences in favour of established American actors such as Burt Reynolds, Chan was impressed by the outtakes shown at the closing credits, inspiring him to include the same device in his future films.

After the commercial failure of The Protector in 1985, Chan temporarily abandoned his attempts to break into the US market, returning his focus to Hong Kong films.[20]

Back in Hong Kong, Chan's films began to reach a larger audience in East Asia, with early successes in the lucrative Japanese market including The Young Master (1980) and Dragon Lord (1982). The Young Master went on to beat previous box office records set by Bruce Lee and established Chan as Hong Kong cinema's top star. With Dragon Lord, he began experimenting with elaborate stunt action sequences,[25] including the final fight scene where he performs various stunts, including one where he does a back flip off a loft and falls to the lower ground.[26]

Chan produced a number of action comedy films with his opera school friends Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao. The three co-starred together for the first time in 1983 in Project A, which introduced a dangerous stunt-driven style of martial arts that won it the Best Action Design Award at the third annual Hong Kong Film Awards.[27] Over the following two years, the "Three Brothers" appeared in Wheels on Meals and the original Lucky Stars trilogy.[28][29] In 1985, Chan made the first Police Story film, a US-influenced action comedy in which Chan performed a number of dangerous stunts. It was named the "Best Film" at the 1986 Hong Kong Film Awards.[30] In 1986, Chan played "Asian Hawk," an Indiana Jones-esque character, in the film Armour of God. The film was Chan's biggest domestic box office success up to that point, grossing over HK$35 million.[31]

Acclaimed sequels and Hollywood breakthrough: 1988–1998

In 1988, Chan starred alongside Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao for the last time to date, in the film Dragons Forever. Hung co-directed with Corey Yuen, and the villain in the film was played by Yuen Wah, both of whom were fellow graduates of the China Drama Academy.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Chan starred in a number of successful sequels beginning with Project A Part II and Police Story 2, which won the award for Best Action Choreography at the 1989 Hong Kong Film Awards. This was followed by Armour of God II: Operation Condor, and Police Story 3: Super Cop, for which Chan won the Best Actor Award at the 1993 Golden Horse Film Festival. In 1994, Chan reprised his role as Wong Fei-hung in Drunken Master II, which was listed in Time Magazine's All-Time 100 Movies.[32] Another sequel, Police Story 4: First Strike, brought more awards and domestic box office success for Chan, but did not fare as well in foreign markets.[33]

Chan rekindled his Hollywood ambitions in the 1990s, but refused early offers to play villains in Hollywood films to avoid being typecast in future roles. For example, Sylvester Stallone offered him the role of Simon Phoenix, a criminal in the futuristic film Demolition Man. Chan declined and the role was taken by Wesley Snipes.[34]

Chan finally succeeded in establishing a foothold in the North American market in 1995 with a worldwide release of Rumble in the Bronx, attaining a cult following in the United States that was rare for Hong Kong movie stars.[35] The success of Rumble in the Bronx led to a 1996 release of Police Story 3: Super Cop in the United States under the title Supercop, which grossed a total of US$16,270,600. Chan's first huge blockbuster success came when he co-starred with Chris Tucker in the 1998 buddy cop action comedy Rush Hour,[36] grossing US$130 million in the United States alone.[21] This film made him a Hollywood star, after which he wrote his autobiography in collaboration with Jeff Yang entitled I Am Jackie Chan.

Fame in Hollywood and Dramatization: 1999–2007

In 1998, Chan released his final film for Golden Harvest, Who Am I?. After leaving Golden Harvest in 1999, he produced and starred alongside Shu Qi in Gorgeous a romantic comedy that focused on personal relationships and featured only a few martial arts sequences.[37] Although Chan had left Golden Havest in 1999, the company continued to produce and distribute for two of his films, Gorgeous (1999) and The Accidental Spy (2001). Chan then helped create a PlayStation game in 2000 called Jackie Chan Stuntmaster, to which he lent his voice and performed the motion capture.[38] He continued his Hollywood success in 2000 when he teamed up with Owen Wilson in the Western action comedy Shanghai Noon which spawned the sequel Shanghai Knights (2003).[39] He reunited with Chris Tucker for Rush Hour 2 (2001) which was an even bigger success than the original grossing $347 million worldwide. He experimented with special effects with The Tuxedo (2002) and The Medallion (2003) which were not as successful critically or commercially. In 2004 he teamed up with Steve Coogan in the big-budget loose adaptation of Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days.

Despite the success of the Rush Hour and Shanghai Noon films, Chan became frustrated with Hollywood over the limited range of roles and lack of control over the filmmaking process.[40] In response to Golden Harvest's withdrawal from the film industry in 2003, Chan started his own film production company, JCE Movies Limited (Jackie Chan Emperor Movies Limited) in association with Emperor Multimedia Group (EMG).[21] His films have since featured an increasing number of dramatic scenes while continuing to succeed at the box office; examples include New Police Story (2004), The Myth (2005) and the hit film Rob-B-Hood (2006).[41][42][43]

Chan's next release was the third instalment in the Rush Hour series: Rush Hour 3 in August 2007. It grossed US$255 million.[44] However, it was a disappointment in Hong Kong, grossing only HK$3.5 million during its opening weekend.[45]

New experiments and change in style: 2008–present

Filming of The Forbidden Kingdom (released in 2008), Chan's first onscreen collaboration with fellow Chinese actor Jet Li, was completed on 24 August 2007 and the movie was released in April 2008. The movie featured heavy use of effects and wires.[46][47] Chan voiced Master Monkey in Kung Fu Panda (released in June 2008), appearing with Jack Black, Dustin Hoffman, and Angelina Jolie.[48] In addition, he has assisted Anthony Szeto in an advisory capacity for the writer-director's film Wushu, released on 1 May 2008. The film stars Sammo Hung and Wang Wenjie as father and son.[49]

In November 2007, Chan began filming Shinjuku Incident, a dramatic role featuring no martial arts sequences with director Derek Yee, which sees Chan take on the role of a Chinese immigrant in Japan.[50] The film was released on 2 April 2009. According to his blog, Chan discussed his wishes to direct a film after completing Shinjuku Incident, something he has not done for a number of years.[51] The film expected to be the third in the Armour of God series, and had a working title of Armour of God III: Chinese Zodiac. The film was released on 12 December 2012.[52] Because the Screen Actors Guild did not go on strike, Chan started shooting his next Hollywood movie The Spy Next Door at the end of October in New Mexico.[53] In The Spy Next Door, Chan plays an undercover agent whose cover is blown when he looks after the children of his girlfriend. In Little Big Soldier, Chan stars, alongside Leehom Wang as a soldier in the Warring States period in China. He is the lone survivor of his army and must bring a captured enemy soldier Leehom Wang to the capital of his province.

In 2010 he starred with Jaden Smith in The Karate Kid, a remake of the 1984 original.[54] This was Chan's first dramatic American film. He plays Mr. Han, a kung fu master and maintenance man who teaches Jaden Smith's character kung fu so he can defend himself from school bullies. His role in The Karate Kid Jackie Chan the Favorite Buttkicker award at the Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards in 2011.[55]

In Chan's next movie, Shaolin, he plays the cook of the temple instead of one of the major characters.

His 100th movie, 1911, was released on 26 September 2011. Chan was the co-director, executive producer, and lead star of the movie.[56] While Chan has directed over ten films over his career, this was his first directorial work since Who Am I? in 1998. 1911 premiered in North America on 14 October.[57]

While at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, Chan announced that he was retiring from action films citing that he was getting too old for the genre. He later clarified that he would not be completely retiring from action films, but would be performing fewer stunts and taking care of his body more.[58]

In 2015, Chan was awarded the title of "Datuk" by Malaysia as he helped Malaysia to boost its tourism, especially in Kuala Lumpur where he previously shot his films.[59] Upcoming films include the Indo-China project titled "Kung Fu Yoga" which also stars Sonu Sood and Amyra Dastur. The film also reunites Chan with director Stanley Tong, who directed a number of Chan's films in the 1990s.

Music career

Chan had vocal lessons whilst at the Peking Opera School in his childhood. He began producing records professionally in the 1980s and has gone on to become a successful singer in Hong Kong and Asia. He has released 20 albums since 1984 and has performed vocals in Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese, Taiwanese and English. He often sings the theme songs of his films, which play over the closing credits. Chan's first musical recording was "Kung Fu Fighting Man", the theme song played over the closing credits of The Young Master (1980).[60] At least 10 of these recordings have been released on soundtrack albums for the films.[61][62] His Cantonese song Story of a Hero (英雄故事) (theme song of Police Story) was selected by the Royal Hong Kong Police and incorporated into their recruitment advertisement in 1994.[63]

Chan voiced the character of Shang in the Chinese release of the Walt Disney animated feature, Mulan (1998). He also performed the song "I'll Make a Man Out of You", for the film's soundtrack. For the US release, the speaking voice was performed by B.D. Wong and the singing voice was done by Donny Osmond.

In 2007, Chan recorded and released "We Are Ready", the official one-year countdown song to the 2008 Summer Olympics which he performed at a ceremony marking the one-year countdown to the 2008 Summer Paralympics.[64] Chan also released one of the two official Olympics albums, Official Album for the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games – Jackie Chan's Version, which featured a number of special guest appearances.[65] Chan performed "Hard to Say Goodbye" along with Andy Lau, Liu Huan and Wakin (Emil) Chau, at the 2008 Summer Olympics closing ceremony.[66]

Academic career

Chan received his Doctor of Social Science degree in 1996 from the Hong Kong Baptist University.[67] In 2009, he received another honorary doctorate from the University of Cambodia,[68][69] and has also been awarded an honorary professorship by the Savannah College of Art and Design in Hong Kong in 2008.[70]

Prof Chan is currently a faculty member of the School of Hotel and Tourism Management at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University,[71] where he teaches the subject of tourism management. As of 2015, he also serves as the Dean of the Jackie Chan Film and Television Academy under the Wuhan Institute of Design and Sciences.[72]

Personal life

In 1982, Chan married Lin Feng-jiao (a.k.a. Joan Lin), a Taiwanese actress. Their son, singer and actor Jaycee Chan, was born that same year.[40] As a result of an extra-marital affair with Chan, Elaine Ng Yi-Lei bore a daughter in 1999.[73][74][75] He speaks Cantonese, Mandarin, English, and American Sign Language and also speaks some German, Korean, Japanese, Spanish, and Thai.[76] Chan is an avid football fan and supports the Hong Kong national football team, England National Football Team, and Manchester City.[77]

Stunts and screen persona

Chan has performed most of his own stunts throughout his film career, which are choreographed by the Jackie Chan Stunt Team. He has stated in interviews that the primary inspiration for his more comedic stunts were films such as The General directed by and starring Buster Keaton, who was also known to perform his own stunts. Since its establishment in 1983, Chan has used the team in all his subsequent films to make choreographing easier, given his understanding of each member's abilities.[78] Chan and his team undertake many of the stunts performed by other characters in his films, shooting the scenes so that their faces are obscured.[79]

The dangerous nature of his stunts makes it difficult for Chan to get insurance, especially in the United States, where his stunt work is contractually limited.[79] Chan holds the Guinness World Record for "Most Stunts by a Living Actor", which emphasises "no insurance company will underwrite Chan's productions in which he performs all his own stunts".[80]

Chan has been injured frequently when attempting stunts; many of them have been shown as outtakes or as bloopers during the closing credits of his films. He came closest to death filming Armour of God, when he fell from a tree and fractured his skull. Over the years, Chan has dislocated his pelvis and also broken numerous parts of body including his fingers, toes, nose, both cheekbones, hips, sternum, neck, ankle, and ribs.[81][82] Promotional materials for Rumble in the Bronx emphasised that Chan performed all of the stunts, and one version of the movie poster even diagrammed his many injuries.

Chan created his screen persona as a response to the late Bruce Lee, and the numerous imitators who appeared before and after Lee's death. In contrast to Lee's characters, who were typically stern, morally upright heroes, Chan plays well-meaning, slightly foolish regular men (often at the mercy of their friends, girlfriends or families) who always triumph in the end despite the odds.[18] Additionally, Chan has stated that he deliberately styles his movement to be the opposite of Lee's: where Lee held his arms wide, Chan holds his tight to the body; where Lee was loose and flowing, Chan is tight and choppy. Despite the success of the Rush Hour series, Chan has stated that he is not a fan of it since he neither appreciates the action scenes in the movie, nor understands American humour.[83]

In the 2000s, the ageing Chan grew tired of being typecast as an action hero, prompting him to act with more emotion in his latest films.[84] In New Police Story, he portrayed a character suffering from alcoholism and mourning his murdered colleagues.[61] To further shed the image of "nice guy", Chan played an anti-hero for the first time in Rob-B-Hood starring as Thongs, a burglar with gambling problems.[85] In 2009's Shinjuku Incident, a serious drama about unsavory characters set in Tokyo, Chan plays a low-level gangster.[86]

Image and celebrity status

Chan has received worldwide recognition for his acting and stunt work. His awards include the Innovator Award from the American Choreography Awards and a lifetime achievement award from the Taurus World Stunt Awards.[87] He has stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and the Hong Kong Avenue of Stars.[88] In addition, Chan has also been honoured by placing his hand and footprints at Grauman's Chinese Theatre.[89] Despite considerable box office success in the Northsouth Territories, Chan's American films have been criticised with regard to their action choreography. Reviewers of Rush Hour 2, The Tuxedo, and Shanghai Knights criticised the toning down of Chan's fighting scenes, citing less intensity compared to his earlier films.[90][91][92] The comedic value of his films is questioned; some critics stating that they can be childish at times.[93] Chan was awarded the MBE in 1989 and the Silver Bauhinia Star (SBS) in 1999.

Chan has been the subject of Ash's song "Kung Fu", Heavy Vegetable's "Jackie Chan Is a Punk Rocker", Leehom Wang's "Long Live Chinese People", as well as in "Jackie Chan" by Frank Chickens, and television shows Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!, Celebrity Deathmatch and Family Guy. He has been the inspiration for manga such as Dragon Ball (including a character with the alias "Jackie Chun"),[94] the character Lei Wulong in Tekken and the fighting-type Pokémon Hitmonchan.[95][96][97]

Jackie Chan has a sponsorship deal with Mitsubishi Motors that has resulted in the appearance of Mitsubishi cars in a number of his films. Furthermore, Mitsubishi launched a limited series of Evolution cars personally customised by Chan.[98][99][100]

A number of video games have featured Chan. Jackie Chan's Action Kung Fu was released in 1990 for the PC-Engine and NES. In 1995, Chan was featured in the arcade fighting game Jackie Chan The Kung-Fu Master. A series of Japanese games were released on the MSX by Pony, based on several of Chan's films (Project A, Project A 2, Police Story, The Protector and Wheels on Meals).[101]

Chan says he has always wanted to be a role model to children, and has remained popular with them due to his good-natured acting style. He has generally refused to play villains and has been very restrained in using swear words in his films – he persuaded the director of Rush Hour to take "fuck" out of the script.[102] Chan's greatest regret in life is not having received a proper education,[103] inspiring him to fund educational institutions around the world. He funded the construction of the Jackie Chan Science Centre at the Australian National University[104] and the establishment of schools in poor regions of China.[105]

Chan is a spokesperson for the Government of Hong Kong, appearing in public service announcements. In a Clean Hong Kong commercial, he urged the people of Hong Kong to be more considerate with regards to littering, a problem that has been widespread for decades.[106] Furthermore, in an advertisement promoting nationalism, he gave a short explanation of the March of the Volunteers, the national anthem of the People's Republic of China.[107] When Hong Kong Disneyland opened in 2005, Chan participated in the opening ceremony.[108] In the United States, Chan appeared alongside Arnold Schwarzenegger in a government advert to combat copyright infringement and made another public service announcement with Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca to encourage people, especially Asians, to join the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department.[109][110]

Construction has begun on a Jackie Chan museum in Shanghai. In November 2013 a statue of Chan was unveiled in front of what is now known as the JC Film Gallery, scheduled to open in the spring of 2014.[111]

On 25 June 2013, Chan responded to a hoax Facebook page created a few days earlier that alleged he had died. He said that several people contacted him to congratulate him on his recent engagement, and soon thereafter contacted him again to ask if he was still alive. He posted a Facebook message, commenting: "If I died, I would probably tell the world!"[112][113]

On 1 February 2015, Chan was awarded the title of Panglima Mahkota Wilayah by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong of Malaysia Tuanku Abdul Halim in conjunction with the country's Federal Territory Day. It carries the title of Datuk in Malaysia.[114][115]

In 2015, a made-up word inspired by Chan's description of his hair during an interview for a commercial, duang, became an internet viral meme in China. The Chinese character for the word is a composite of two characters of Chan's name.[116]

Political views and controversy

During a news conference in Shanghai on 28 March 2004, Chan referred to the recently concluded Republic of China 2004 presidential election in Taiwan, in which Democratic Progressive Party candidates Chen Shui-bian and Annette Lu were re-elected as President and Vice-President, as "the biggest joke in the world".[117][118][119] A Taiwanese legislator and senior member of the DPP, Parris Chang, called for the government of Taiwan to ban his films and bar him the right to visit Taiwan.[117] Police and security personnel separated Chan from scores of protesters shouting "Jackie Chan, get out" when he arrived at Taipei airport in June 2008.[120]

Referring to his participation in the torch relay for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, Chan spoke out against demonstrators who disrupted the relay several times attempting to draw attention to a wide-ranging number of grievances against the Chinese government. He warned that "publicity seekers" planning to stop him from carrying the Olympic Torch "not get anywhere near" him. Chan also argued that China was attempting reform and that the Olympics coverage that year would be a chance for the country to learn from the outside world.[121]

In 2009, Chan was named an "anti-drug ambassador" by the Chinese government, actively taking part in anti-drug campaigns and supporting President Xi Jinping's declaration that illegal drugs should be eradicated, and their users punished severely. In 2014, when his own son Jaycee was arrested for cannabis use, he said that he was "angry", "shocked", "heartbroken" and "ashamed" of his son. He also remarked, "I hope all young people will learn a lesson from Jaycee and stay far from the harm of drugs. I say to Jaycee that you have to accept the consequences when you do something wrong."[122]

On 18 April 2009, during a panel discussion at the annual Boao Forum for Asia, he questioned whether or not broad freedom is a good thing.[123] Noting the strong tensions in Hong Kong and Taiwan, he said, "I'm gradually beginning to feel that we Chinese need to be controlled. If we're not being controlled, we'll just do what we want."[124][125] Chan's comments prompted angry responses from several prominent figures in Taiwan and Hong Kong.[126][127] A spokesman later said Chan was referring to freedom in the entertainment industry, rather than in Chinese society at large.[128]

In December 2012, Chan caused outrage when he criticised Hong Kong as a "city of protest", suggesting that demonstrators' rights in Hong Kong should be limited.[129] The same month, in an interview with Phoenix TV, Chan stated that the United States was the "most corrupt" country in the world,[130][131] which in turn angered parts of the online community[131] and prompted a critical response from journalist Max Fisher, who argued that Chan's comments were rooted "not just in attitudes toward America but in China's proud but sometimes insecure view of itself."[132] Other articles situated Chan's comments in the context of his career and life in the United States, including his "embrace of the American film market"[132] and his seeking asylum in the United States from Hong Kong triads.[133]

In April 2016, Chan was named in the Panama Papers.[134]

Entrepreneurship and philanthropy

In addition to his film production and distribution company, JCE Movies Limited, Jackie Chan also owns or co-owns the production companies JC Group China, Jackie & Willie Productions[135] (with Willie Chan) and Jackie & JJ Productions.[136] Chan has also put his name to Jackie Chan Theater International, a cinema chain in China, co-run by Hong Kong company Sparkle Roll Group Ltd. The first—Jackie Chan-Yaolai International Cinema—opened in February 2010, and is claimed to be the largest cinema complex in China, with 17 screens and 3,500 seats. Chan expressed his hopes that the size of the venue would afford young, non-commercial directors the opportunity to have their films screened. 15 further cinemas in the chain are planned for 2010,[needs update] throughout Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, with a potential total of 65 cinemas throughout the country proposed.[137][138]

In 2004, Chan launched his own line of clothing, which bears a Chinese dragon logo and the English word "Jackie", or the initials "JC".[139] Chan also has a number of other branded businesses. His sushi restaurant chain, Jackie's Kitchen, has outlets throughout Hong Kong, as well as seven in South Korea, with plans to open another in Las Vegas. Jackie Chan's Cafe has outlets in Beijing, Singapore, and the Philippines. Other ventures include Jackie Chan Signature Club gyms (a partnership with California Fitness), and a line of chocolates, cookies and nutritional oatcakes.[140] With each of his businesses, a percentage of the profits goes to various charities, including the Jackie Chan Charitable Foundation.

Chan is a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, and has championed charitable works and causes. He has campaigned for conservation, against animal abuse and has promoted disaster relief efforts for floods in mainland China and the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.[8][141][142]

In June 2006, citing his admiration of the efforts made by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates to help those in need, Chan pledged the donation of half his assets to charity upon his death.[143] On 10 March 2008, Chan was the guest of honour for the launch, by Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, of the Jackie Chan Science Centre at the John Curtin School of Medical Research of the Australian National University. Chan is also a supporter and ambassador of Save China's Tigers, which aims to save the endangered South China tiger through breeding and releasing them into the wild.[144] Following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, Chan donated RMB ¥10 million to help those in need. In addition, he is planning to make a film about the Chinese earthquake to raise money for survivors.[145] In response to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Chan and fellow Hong Kong-based celebrities, including American rapper MC Jin, headlined a special three-hour charity concert, titled Artistes 311 Love Beyond Borders, on 1 April 2011 to help with Japan's disaster recovery effort.[146][147] The 3-hour concert raised over $3.3 million.[148]

Chan founded the Jackie Chan Charitable Foundation in 1988, to offers scholarship and active help to Hong Kong's young people and provide aid to victims of natural disaster or illness.[4] In 2005 Chan created the Dragon's Heart Foundation to help children and the elderly in remote areas of China by building schools, providing books, fees, and uniforms for children; the organisation expanded its reach to Europe in 2011.[149][150] The foundation also provides for the elderly with donations of warm clothing, wheelchairs, and other items.

Awards and nominations

| ||||||||

| Totals[a] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | 34 | |||||||

Note

| ||||||||

- 8th American Choreography Innovator Awards – Won[151]

- 1993 Asia-Pacific Film Lifetime Achievement Award – Won

- 2005 Asia-Pacific Film Special Jury Award – Won

- 2000 Special Award for Global Impact – Won

- 1999 Favorite Duo – Action/Adventure (for Rush Hour) – Won

- 2001 Favorite Action Team (for Shanghai Noon) – Nominated

- 1998 Maverick Spirit Award – Won

- 2002 Performer in an Animated Program (for Jackie Chan Adventures) – Nominated

- 1997 Best Asian Film (for Drunken Master II) – Won (shared with Chia-Liang Liu)

- 1992 Best Actor (for Police Story 3: Super Cop) – Won

- 1993 Best Actor (for Crime Story) – Won

- 2005 Outstanding Contribution Award – Won

- 2005 Best Actor (for New Police Story) – Won

- 1999 Actor of the Year – Won

- 1983 Best Action Choreography (for Dragon Lord) – Nominated (shared with Hark-On Fung and Yuen Kuni)

- 1985 Best Actor (for Project A) – Nominated

- 1986 Best Director (for Police Story) – Nominated

- 1986 Best Actor (for Police Story) – Nominated

- 1986 Best Actor (for Heart of Dragon) – Nominated

- 1989 Best Picture (for Rouge) – Won

- 1990 Best Actor (for Miracles) – Nominated

- 1993 Best Actor (for Supercop) – Nominated

- 1994 Best Actor (for Crime Story) – Nominated

- 1994 Best Action Choreography (for Crime Story) – Nominated

- 1996 Best Actor (for Rumble in the Bronx) – Nominated

- 1996 Best Action Choreography (for Rumble in the Bronx) – Won

- 1997 Best Actor (for Dragon Lord) – Nominated

- 1999 Best Actor (for Who Am I?) – Nominated

- 1999 Best Action Choreography (for Who Am I?) – Won

- 2000 Best Action Choreography (for Gorgeous) – Nominated (shared with Jackie Chan Stunt Team)

- 2005 Best Actor (for New Police Story) – Nominated

- 2005 Professional Achievement Award – Won

- 2006 Best Original Film Song (for The Myth) – Nominated (shared with Choi Jun Young, Wang Zhong Yan, and Hee-seon Kim)

- 2006 Best Action Choreography (for The Myth) – Nominated (shared with Stanley Tong, Tak Yuen)

- 2007 Best Action Choreography (for Robin-B-Hood) – Nominated (shared with Chung Chi Li)

- 2010 Best Film (for Shinjuku Incident) – Nominated

- 2013 Best Action Choreography (for CZ12) – Won

- 2006 Best Actor (for New Police Story) – Nominated

- 2002 Favorite Male Movie Star (for Rush Hour 2) – Nominated

- 2002 Favorite Male Action Hero (for Rush Hour 2) – Won

- 2003 Favorite Movie Actor (for The Tuxedo) – Nominated

- 2003 Favorite Male Butt Kicker (for The Tuxedo) – Won

- 2011 Favorite Butt Kicker (for The Karate Kid) – Won

- Grand Prix des Amériques – Won

- 1995 Lifetime Achievement Award – Won

- 1996 Best Fight (for Rumble in the Bronx) – Nominated

- 1997 Best Fight (for Police Story 4: First Strike) – Nominated

- 1999 Best Fight (for Rush Hour) – Nominated (shared with Chris Tucker)

- 1999 Best On-Screen Duo (for Rush Hour) – Won (shared with Chris Tucker)

- 2002 Best On-Screen Team (for Rush Hour 2) – Nominated (shared with Chris Tucker)

- 2002 Best Fight (for Rush Hour 2) – Won (shared with Chris Tucker)

- 2003 Best On-Screen Team (for Shanghai Knights) – Nominated (shared with Owen Wilson)

- 2008 Best Fight (for Rush Hour 3) – Nominated (shared with Chris Tucker and Sun Mingming)

- 2008 Favorite on Screen Match-up (for Rush Hour 3) – Nominated (shared with Chris Tucker)

- 2011 Favorite On-Screen Team (for The Karate Kid) – Nominated (shared with Jaden Smith)

- 2011 Favorite Action Star – Won

Shanghai International Film Festival

- 2005 Outstanding Contribution to Chinese Cinema – Won

- 2002 Film – Choice Chemistry (for Rush Hour 2) – Nominated (shared with Chris Tucker)

- 2008 Choice Movie Actor: Action Adventure (for The Forbidden Kingdom) – Nominated

- 2002 Motion Picture – Won (Star on the Walk of Fame)

- 2002 Taurus Honorary Award – Won

See also

References

- ^ "No. 51772". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 16 June 1989. - ^ "Jackie Chan Panglima Mahkota Wilayah". MalaysianReview.com. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "Biography section, official website of Jackie". Jackiechan.com. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ a b Ron Gluckman (22 June 2011). "Jackie Chan: Philanthropy's Hardest Working Man". Forbes. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ Mandle, Chris. "Jackie Chan in second place in Forbes' Highest Paid Actors list after magazine includes actors working outside US movie industry", The Independent, published 4 August 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Biography of Jackie Chan". Biography. Hong Kong Film.net. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Biography of Jackie Chan". Biography. Tiscali. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Jackie Chan Battles Illegal Wildlife Trade". Celebrity Values. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Biography of Jackie Chan". StarPulse. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Seven Little Fortunes". Feature article. LoveAsianFilm. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan's Hapkido Master". Web-vue.com. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ "Come Drink With Me (1966)". Database entry. Hong Kong Cinemagic. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b Who Am I?, Star file: Jackie Chan (DVD). Universe Laser, Hong Kong. 1998.

- ^ "Men of the Week: Entertainment, Jackie Chan". Biography. AskMe. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Real Lives: Jackie Chan". Biography. The Biography Channel. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan als Darsteller in altem Sexfilm aufgetaucht". Information Times (in German). 2006. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Boogs, Monika (7 March 2002). "Jackie Chan's tears for 'greatest' mother". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Jackie Chan – Actor and Stuntman". BBC. 24 July 2001. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ lily. "Jackie Chan: Chinese Kung Fu Superstar". ChinaA2Z.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Jackie Chan, a martial arts success story". Biography. Fighting Master. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Jackie Chan Biography (an Asian perspective)". Biography. Ng Kwong Loong (JackieChanMovie.com). Archived from the original on 2 April 2004. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Pollard, Mark. "Snake in the Eagle's Shadow". Movie review. Kung Fu Cinema. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Pollard, Mark. "Drunken Master". Movie review. Kung Fu Cinema. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "The Big Brawl". Variety. 31 December 1979. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Dragon Lord". Love HK Film. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ David Everitt (16 August 1996). "Kicking and Screening: Wheels on Meals, Armour of God, Police Story, and more are graded with an eye for action". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Project A Review". Film review. Hong Kong Cinema. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Sammo Hung Profile". Kung Fu Cinema. Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Yuen Biao Profile". Kung Fu Cinema. Archived from the original on 15 April 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Mills, Phil. "Police Story (1985)". Film review. Dragon's Den. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Armour of God". jackiechanmovie.com. 2006. Archived from the original on 3 September 2004. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Drunken Master II – All-Time 100 Movies". Time. 12 February 2005. Archived from the original on 11 July 2005. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Kozo. "Police Story 4 review". Film review. LoveHKFilm. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Dickerson, Jeff (4 April 2002). "Black Delights in Demolition Man". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Morris, Gary (April 1996). "Rumble in the Bronx review". Bright Lights Film Journal. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Rush Hour Review". Film Review. BeijingWushuTeam.com. 15 September 1998. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Jackie Chan (1999). Gorgeous, commentary track (DVD). Uca Catalogue.

- ^ Gerstmann, Jeff (14 January 2007). "Jackie Chan Stuntmaster Review". Gamespot. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Mark Caro (6 February 2003). "Movie Review, 'Shanghai Knights'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ a b Chan, Jackie. "Jackie Chan Biography". Official website of Jackie Chan. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ "New Police Story Review". LoveHKFilm. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "The Myth Review". Karazen. Archived from the original on 28 October 2005. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Rob-B-Hood Review". HkFlix. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Rush Hour 3 Box Office Data". Box Office Mojo. 2006. Archived from the original on 29 October 2004. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan's 'Rush Hour 3' struggles at Hong Kong box office". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 21 August 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2004. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 23 October 2007 suggested (help) - ^ "The Forbidden Kingdom". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan and Jet Li Will Fight In 'Forbidden Kingdom'". CountingDown. 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ LaPorte, Nicole; Gardner, Chris (8 November 2005). "'Panda' battle-ready". Variety. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (2 November 2007). "'Wushu' gets its wings". Variety. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Shinjuku Incident Starts Shooting in November". News Article. jc-news.net. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Chan, Jackie (29 April 2007). "Singapore Trip". Blog. Official Jackie Chan Website. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Jackie Chan's Operation Condor 3". News Article. Latino Review Inc. 1 August 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Lee, Min (7 August 2008). "Jackie Chan to star in Hollywood spy comedy". USA Today. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Warmoth, Brian. "'Karate Kid' Remake Keeping Title, Taking Jaden Smith to China". MTV Movie Blog. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Grace Li (5 April 2011). "Jackie Chan wins Kids' Choice Award". Asia Pacific Arts. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Lei Jin (18 February 2011). "Jackie Chan's 100th film gets release". Asia Pacific Arts. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Liuyi (Luisa) Chen (13 October 2011). "Jackie Chan's 100th film, 1911, premieres in North America this Friday". Asia Pacific Arts. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Belinda Goldsmith (17 May 2013). "Jackie Chan wants to be serious but will never quit action films". Reuters. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Khairy Jamaluddin (2 February 2015). "Hong Kong superstar Jackie Chan awarded title of Datuk by Malaysia". The Strait Times. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Jackie Chan: Kung Fu Fighter Believes There's More to Him Than Meets the Eye". hkvpradio (Hong Kong Vintage Pop Radio). Archived from the original on 31 December 2003. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b Jackie Chan (2004). New Police Story (DVD). Hong Kong: JCE Movies Limited.

- ^ Jackie Chan (2006). Rob-B-Hood (DVD). Hong Kong: JCE Movies Limited.

- ^ 警務處 (香港皇家警察招募) – 警察故事 (Television advertisement). Hong Kong: Royal Hong Kong Police. 1994.

- ^ "We Are Ready". Jackie Chan Kids. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan releases Olympic album". China Daily. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Beijing Olympic closing ceremony press conference". TVB News World. 23 August 2008. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Professor Jackie Chan, Personal Introduction" (PDF). School of Hotel and Tourism Management, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Jackie visits the University of Cambodia". jackiechan.com. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Press Release". Phnom: University of Cambodia. 10 November 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan Named Honorary Professor by U.S. college". China Daily. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Academic Staff". School of Hotel and Tourism Management, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Kung fu superstar Chan launches film and television academy". China Daily. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Fans desert Jackie Chan". BBC. 31 March 2000. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Elaine Ng moves back to Hong Kong". celebritygossip.asia. 31 July 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "小龍女富貴臉 像房祖名 ("Dragon"'s daughter has a wealthy appearance; looks like Jaycee Chan)". 20 May 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "An interview with Jackie Chan". Empire (104): 5. 1998.

- ^ "Extra Time: Manchester City fan Jackie Chan in good Kompany". Goal.com. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Jackie Chan (1987). Police Story Commentary (DVD). Hong Kong: Dragon Dynasty.

- ^ a b Rogers, Ian. "Jackie Chan Interview". FilmZone. Archived from the original on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "January 2003 News Archives". Jackie Chan Kids. 3 January 2003. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Chan, Jackie. "The Official Jackie Chan Injury Map". Jackie Chan Kids. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan re-injures back while filming". The Star. Malaysia. 27 August 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan Admits He Is Not a Fan of 'Rush Hour' Films". Fox News Channel. 30 September 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan: From action maestro to serious actor". China Daily. 24 September 2004. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "For the first time, Chan plays an unconventional role in his newest comedy (成龙首次尝试反派 联手陈木胜再拍动作喜剧)" (in Chinese). Sina Corp. 30 December 2005. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan: The Young Master Comes of Age". Asia Society. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Jackie Chan From Hong Kong to Receive Stunt Award". Xinhuanet. 16 May 2002. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Ortega, Albert (4 October 2002). "Jackie Chan Honored with a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame". EZ-Entertainment. Archived from the original on 25 April 2003. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Jackie Chan replaces missing Hollywood hand prints

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (30 July 2001). "Rush Hour 2 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (27 September 2002). "The Tuxedo Review". Official website of Roger Ebert. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Pierce, Nev (3 April 2003). "Shanghai Knights Review". BBC film. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (16 June 2004). "Around the World in 80 Days Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Hebert, James (22 August 2003). "Inspiration for Dragonball". San Diego Tribune. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Masters of the Martial Arts". Celebrity Deathmatch. Season 1. Episode 12. 1999.

{{cite episode}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|episodelink=(help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ "Breaking Out Is Hard to Do". Family Guy. Season 4. Episode 9. 17 July 2005.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|episodelink=ignored (|episode-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Orecklin, Michael (10 May 1999). "Pokemon: The Cutest Obsession". Time.

- ^ Chan, Jackie. "Note From Jackie: My Loyalty Toward Mitsubishi 19 June 2007". Official website of Jackie Chan. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "E! Online Question and Answer (Jackie Chan)". Jackie Chan Kids. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Chan, Jackie. "Trip to Shanghai; Car Crash!! 18–25 April 2007". Official website of Jackie Chan. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan Video Games". Hardcore Gaming 101. 6 February 2010.

- ^ "Jackie Chan Wants to Be Role Model". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 4 August 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Webb, Adam (29 September 2000). "Candid Chan: Action star Jackie Chan takes on students' questions". The Flat Hat. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "ANU to name science centre after Jackie Chan" (Press release). Australia National University. 24 February 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Biography of Jackie Chan (Page 8)". Biography. Tiscali. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Jackie Chan (2002). Clean Hong Kong (Television). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government.

- ^ Agencies (18 May 2005). "Hong Kong marshal Jackie Chan to Boost Nationalism". China Daily. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan, Chow Yun-fat among VIPs invited to HK Disneyland opening". Sina Corp. Associated Press. 18 August 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Schwarzenegger, Arnold; Jackie Chan. "Anti-piracy advert". Advertisement. United States Government. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ "Jackie Chan stars in LAPD recruitment campaign". China Daily. 11 March 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Fei Lai (9 November 2013). "Jackie Chan wants to be serious but will never quit action films". Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ "Jackie Chan response to RIP hoax". United Press International. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Jackie Chan declares well-being". Yahoo!. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Jackie Chan now a Datuk". The Star Online. 1 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Jackie Chan given Datuk title". Yahoo! Entertainment Singapore. 1 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Millions share new Chinese character". BBC. 2 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Taiwan lawmaker calls for Jackie Chan movie ban". China Daily. 22 April 2004. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Taiwan election biggest joke in the world". China Daily. 29 March 2004. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Protestors blast Jackie Chan for criticizing Taiwan elections". People News. 18 June 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Protesters greet Jackie Chan in Taiwan". ABC News (Australia). 19 June 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Kung-fu star Jackie Chan to chop down Olympic protesters". Metro. UK. 15 April 2008. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan shocked and angry over son's drug arrest". CBC News. Canada. 20 August 2014.

- ^ Min Lee (21 April 2009). "Spokesman: Jackie Chan comments out of context". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ William Foreman (18 April 2009). "Jackie Chan: Chinese people need to be controlled". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan warns over China 'chaos': report". Yahoo! News. 19 April 2009. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Coonan, Clifford (20 April 2009). "Chinese shouldn't get more freedom, says Jackie Chan". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Le-Min Lim (22 April 2009). "Jackie Chan Faces Film Boycott for Chaotic Taiwan Comments". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan's 'freedom' talk sparks debate". People's Daily. 22 April 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Colleen Lee and Tony Cheung (13 December 2012). "Jackie Chan criticises Hong Kong as 'city of protest'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ "Jackie Chan calls America 'most corrupt country in the world'". Daily Mail. 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b Chow, Vivienne (12 January 2013). "Jackie Chan back in action, branding US more corrupt than China". South China Morning Post.

- ^ a b Fisher, Max (10 January 2013). "The anti-Americanism of Jackie Chan". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Actor Jackie Chan calls U.S. 'most corrupt' country in the world". Agence France-Presse. 12 January 2013.

- ^ "From Kubrick to Cowell: Panama Papers expose offshore dealings of the stars". The Guardian. 6 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Jackie & Willie Productions Limited". Film database entry (Studios). HKCinemagic. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ "Jackie & JJ Productions Ltd – Hong Kong". Business index entry. HKTDC. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan launches cinema chain claiming to be the largest in China". News report. CCTV.com. 13 February 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Gregg Kilday and David Morgan (13 May 2010). "Jackie Chan plans turbo-charged slate". Film news report. THR Asia (Hollywood Reporter). Archived from the original on 18 May 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Fashion leap for Jackie Chan as Kung-fu star promotes new clobber". JC-News. Agence France-Presse. 2 April 2004. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan's business empire kicks into place". Taipei Times. 11 April 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan Urges China to 'Have a Heart' for Dogs". PETA. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "UNICEF People: Jackie Chan: Goodwill Ambassador". UNICEF. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan looks to bequeath half of wealth". The Financial Express. Reuters. 29 June 2006. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Save China's Tigers: Patrons and Supporters". SaveChina'Tigers.org. 22 August 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan plans China earthquake movie". thaindian.com. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "Japan Earthquake Song Music Video". Jackiechan.com. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "Jackie Chan and HK celebrities to raise funds for quake victims in Japan". Xinhua News Agency. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Chu, Karen (4 April 2011). "Jackie Chan Raises $3.3 Million in Three Hours for Japan Relief (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "JC Dragon's Heart Europe & Sanjuro Martial Arts".

- ^ Cavallaro, Albert (5 August 2014). "Celebrities Making a Difference, Part II". BORGEN Magazine. The Borgen Project. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Segal, Lewis (22 October 2002). "Dance awards honor new, unusual". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

Further reading

- Boose, Thorsten; Oettel, Silke. Hongkong, meine Liebe – Ein spezieller Reiseführer. Shaker Media, 2009. ISBN 978-3-86858-255-0 Template:De icon

- Boose, Thorsten. Der deutsche Jackie Chan Filmführer. Shaker Media, 2008. ISBN 978-3-86858-102-7 Template:De icon

- Chan, Jackie, and Jeff Yang. I Am Jackie Chan: My Life in Action. New York: Ballantine Books, 1999. ISBN 0-345-42913-3. Jackie Chan's autobiography.

- Cooper, Richard, and Mike Leeder. 100% Jackie Chan: The Essential Companion. London: Titan Books, 2002. ISBN 1-84023-491-1.

- Cooper, Richard. More 100% Jackie Chan: The Essential Companion Volume 2. London: Titan Books, 2004. ISBN 1-84023-888-7.

- Corcoran, John. The Unauthorized Jackie Chan Encyclopedia: From Project A to Shanghai Noon and Beyond. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2003. ISBN 0-07-138899-0.

- Fox, Dan. Jackie Chan. Raintree Freestyle. Chicago, Ill.: Raintree, 2006. ISBN 1-4109-1659-6.

- Gentry, Clyde. Jackie Chan: Inside the Dragon. Dallas, Tex.: Taylor Pub, 1997. ISBN 0-87833-962-0.

- Le Blanc, Michelle, and Colin Odell. The Pocket Essential Jackie Chan. Pocket essentials. Harpenden: Pocket Essentials, 2000. ISBN 1-903047-10-2.

- Major, Wade. Jackie Chan. New York: Metrobooks, 1999. ISBN 1-56799-863-1.

- Moser, Leo. Made in Hong Kong: die Filme von Jackie Chan. Berlin: Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, 2000. ISBN 3-89602-312-8. Template:De icon

- Poolos, Jamie. Jackie Chan. Martial Arts Masters. New York: Rosen Pub. Group, 2002. ISBN 0-8239-3518-3.

- Rovin, Jeff, and Kathleen Tracy. The Essential Jackie Chan Sourcebook. New York: Pocket Books, 1997. ISBN 0-671-00843-9.

- Stone, Amy. Jackie Chan. Today's Superstars: Entertainment. Milwaukee, Wis.: Gareth Stevens Pub, 2007. ISBN 0-8368-7648-2.

- Witterstaetter, Renee. Dying for Action: The Life and Films of Jackie Chan. New York: Warner, 1998. ISBN 0-446-67296-3.

- Wong, Curtis F., and John R. Little (eds.). Jackie Chan and the Superstars of Martial Arts. The Best of Inside Kung-Fu. Lincolnwood, Ill.: McGraw-Hill, 1998. ISBN 0-8092-2837-8.

External links

- Official website

- Jackie Chan at IMDb

- Jackie Chan at the Hong Kong Movie Database

- Jackie Chan at AllMovie

- Jackie Chan at Rotten Tomatoes

- Jackie Chan on Facebook

- 1954 births

- Living people

- Jackie Chan

- 20th-century Hong Kong male actors

- 21st-century Hong Kong male actors

- Cantopop singers

- Hong Kong male comedians

- Hong Kong entrepreneurs

- Hong Kong male film actors

- Hong Kong film directors

- Hong Kong film producers

- Hong Kong kung fu practitioners

- Chinese Jeet Kune Do practitioners

- Hong Kong judoka

- Male judoka

- Hong Kong taekwondo practitioners

- Hong Kong male singers

- Hong Kong Mandopop singers

- Hong Kong martial artists

- Hong Kong philanthropists

- Hong Kong screenwriters

- Hong Kong male voice actors

- Hong Kong wushu practitioners

- Hong Kong hapkido practitioners

- Members of the Order of the British Empire

- Running Man (TV series) contestants

- Hong Kong stunt performers