Intersex

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

Intersex people are human hermaphrodites. More specifically, an intersex person is a person born with any of several variations in sex characteristics including chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies".[1][2] Such variations may involve genital ambiguity, and combinations of chromosomal genotype and sexual phenotype other than XY-male and XX-female.[3][4]

Intersex people were previously referred to as hermaphrodites, "congenital eunuchs",[5][6] or even congenitally "frigid".[7] Such terms have fallen out of favor; in particular, the term "hermaphrodite" is considered to be misleading, stigmatizing, and scientifically specious.[8] Medical description of intersex traits as disorders of sex development has been controversial[9][10][11] since the label was introduced in 2006.[12]

Intersex people may face stigmatization and discrimination from birth or discovery of an intersex trait. In some countries, documented in parts of Africa and Asia, this may include infanticide, abandonment and the stigmatization of families.[13][14][15] Globally, some intersex infants and children, such as those with ambiguous outer genitalia, are surgically or hormonally altered to create more socially acceptable sex characteristics. However, this is considered controversial, with no firm evidence of good outcomes.[16] Such treatments may involve sterilization. Adults, including elite female athletes, have also been subjects of such treatment.[17][18] Increasingly these issues are considered human rights abuses, with statements from international[19][20] and national human rights and ethics institutions.[21][22] Intersex organizations have also issued statements about human rights violations, including the Malta declaration of the third International Intersex Forum.[23]

In 2011, Christiane Völling became the first intersex person known to have successfully sued for damages in a case brought for non-consensual surgical intervention.[24] In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw non-consensual medical interventions to modify sex anatomy, including that of intersex people.[25][26]

Some intersex persons may be assigned and raised as a girl or boy but then identify with another gender later in life, while most continue to identify with their assigned sex.[4][2][27][28][29]

Definitions

According to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights:

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics (including genitals, gonads and chromosome patterns) that do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies. Intersex is an umbrella term used to describe a wide range of natural bodily variations. In some cases, intersex traits are visible at birth while in others, they are not apparent until puberty. Some chromosomal intersex variations may not be physically apparent at all.[2]

In biological terms, sex may be determined by a number of factors present at birth, including:[30]

- the number and type of sex chromosomes;

- the type of gonads—ovaries or testicles;

- the sex hormones;

- the internal reproductive anatomy (such as the uterus in females); and

- the external genitalia.

People whose characteristics are not either all typically male or all typically female at birth are intersex.[31]

Some intersex traits are not always visible at birth; some babies may be born with ambiguous genitals, while others may have ambiguous internal organs (testes and ovaries). Others will not become aware that they are intersex unless they receive genetic testing, because it does not manifest in their phenotype.

History

Whether or not they were socially tolerated or accepted by any particular culture, the existence of intersex people was known to many ancient and pre-modern cultures. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote of "hermaphroditus" in the first century BCE that Hermaphroditus "is born with a physical body which is a combination of that of a man and that of a woman", and with supernatural properties.[32]

In European societies, Roman law, post-classical canon law, and later common law, referred to a person's sex as male, female or hermaphrodite, with legal rights as male or female depending on the characteristics that appeared most dominant.[33] The 12th-century Decretum Gratiani states that "Whether an hermaphrodite may witness a testament, depends on which sex prevails".[34][35][36] The foundation of common law, the 17th Century Institutes of the Lawes of England described how a hermaphrodite could inherit "either as male or female, according to that kind of sexe which doth prevaile."[37][38] Legal cases have been described in canon law and elsewhere over the centuries.

In some non-European societies, sex or gender systems with more than two categories may have allowed for other forms of inclusion of both intersex and transgender people. Such societies have been characterized as "primitive", while Morgan Holmes states that subsequent analysis has been simplistic or romanticized, failing to take account of the ways that subjects of all categories are treated.[39]

During the Victorian era, medical authors introduced the terms "true hermaphrodite" for an individual who has both ovarian and testicular tissue, "male pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with testicular tissue, but either female or ambiguous sexual anatomy, and "female pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with ovarian tissue, but either male or ambiguous sexual anatomy. Some later shifts in terminology have reflected advances in genetics, while other shifts are suggested to be due to pejorative associations.[40]

The term intersexuality was coined by Richard Goldschmidt in 1917.[41] The first suggestion to replace the term 'hermaphrodite' with 'intersex' was made by Cawadias in the 1940s.[42]

Since the rise of modern medical science, some intersex people with ambiguous external genitalia have had their genitalia surgically modified to resemble either female or male genitals. Surgeons pinpointed intersex babies as a "social emergency" when born.[43] An 'optimal gender policy', initially developed by John Money, stated that early intervention helped avoid gender identity confusion, but this lacks evidence,[44] and early interventions have adverse consequences for psychological and physical health.[22] Since advances in surgery have made it possible for intersex conditions to be concealed, many people are not aware of how frequently intersex conditions arise in human beings or that they occur at all.[45]

Dialog between what were once antagonistic groups of activists and clinicians has led to only slight changes in medical policies and how intersex patients and their families are treated in some locations.[46] In 2011, Christiane Völling became the first intersex person known to have successfully sued for damages in a case brought for non-consensual surgical intervention.[24] In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw non-consensual medical interventions to modify sex anatomy, including that of intersex people.[25] Many civil society organizations and human rights institutions now call for an end to unnecessary "normalizing" interventions, including in the Malta declaration.[47][1]

Human rights and legal issues

Human rights institutions are placing increasing scrutiny on harmful practices and issues of discrimination against intersex people. These issues have been addressed by a rapidly increasing number of international institutions including, in 2015, the Council of Europe, the United Nations Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the World Health Organization. These developments have been accompanied by International Intersex Forums and increased cooperation amongst civil society organizations. However, the implementation, codification and enforcement of intersex human rights in national legal systems remains slow.

Areas of concern include: non-consensual medical interventions; stigma, discrimination and equal treatment; access to reparations and justice; access to information and support, and legal recognition.

Physical integrity and bodily autonomy

Stigmatization and discrimination from birth may include infanticide, abandonment and the stigmatization of families. Mothers in east Africa may be accused of witchcraft, and the birth of an intersex child may be described as a curse.[13][14] Abandonments and infanticides have been reported in Uganda,[13] Kenya,[48] south Asia,[49] and China.[15]

Infants, children and adolescents also experience "normalising" interventions on intersex persons that are medically unnecessary and the unnecessary pathologisation of variations in sex characteristics. Medical interventions to modify the sex characteristics of intersex people, without the consent of the intersex person have taken place in all countries where the human rights of intersex people have been studied.[50] These interventions have frequently been performed with the consent of the intersex person's parents, when the person is legally too young to consent. Such interventions have been criticized by the World Health Organization, other UN bodies such as the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and an increasing number of regional and national institutions due to their adverse consequences, including trauma, impact on sexual function and sensation, and violation of rights to physical and mental integrity.[1] In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw surgical intervention without consent.[25][26] In the same year, the Council of Europe became the first institution to state that intersex people have the right not to undergo sex affirmation interventions.[25][26][51][52][53]

Anti-discrimination and equal treatment

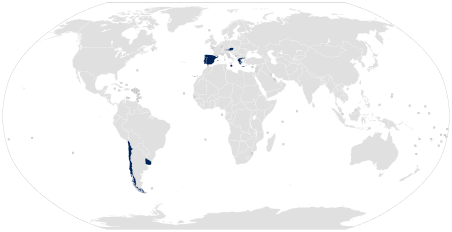

Inclusion in equal treatment and hate crime law. Because people born with intersex bodies are seen as different, intersex infants, children, adolescents and adults "are often stigmatized and subjected to multiple human rights violations", including discrimination in education, healthcare, employment, sport, and public services.[2][1][54] Several countries have so far explicitly protected intersex people from discrimination, with landmarks including South Africa,[26][55] Australia,[56][57] and, most comprehensively, Malta.[58][59][60][61][62]

Reparations and justice

Facilitating access to justice and reparations. Access to reparation appears limited, with a scarcity of legal cases, such as the 2011 case of Christiane Völling in Germany.[24][63] A second case was adjudicated in Chile in 2012, involving a child and his parents.[64][65] A further successful case in Germany, taken by Michaela Raab, was reported in 2015.[66] In the United States, the "M.C." legal case, advanced by Interact Advocates for Intersex Youth with the Southern Poverty Law Centre is still before the courts.[67][68]

Information and support

Access to information, medical records, peer and other counselling and support. With the rise of modern medical science in Western societies, a secrecy-based model was also adopted, in the belief that this was necessary to ensure "normal" physical and psychosocial development.[21][22][69][70][71][72]

Legal recognition

The Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions states that legal recognition is firstly "about intersex people who have been issued a male or a female birth certificate being able to enjoy the same legal rights as other men and women."[23] In some regions, obtaining any form of birth certification may be an issue. A Kenyan court case in 2014 established the right of an intersex boy, "Baby A", to a birth certificate.[73]

Like all individuals, some intersex individuals may be raised as a certain sex (male or female) but then identify with another later in life, while most do not.[3][4][28][29] Recognition of third sex or gender classifications occurs in several countries,[74][75][76][77] however, it is controversial when it becomes assumed or coercive, as is the case with some German infants.[78][79][80] Sociological research in Australia, a country with a third 'X' sex classification, shows that 19% of people born with atypical sex characteristics selected an "X" or "other" option, while 52% are women, 23% men, and 6% unsure.[27][81]

Language

Research in the late 20th century led to a growing medical consensus that diverse intersex bodies are normal, but relatively rare, forms of human biology.[4][82][83][84] Clinician and researcher Milton Diamond stresses the importance of care in the selection of language related to intersex people:

Foremost, we advocate use of the terms "typical", "usual", or "most frequent" where it is more common to use the term "normal." When possible avoid expressions like maldeveloped or undeveloped, errors of development, defective genitals, abnormal, or mistakes of nature. Emphasize that all of these conditions are biologically understandable while they are statistically uncommon.[85]

The term 'intersex'

Some people with intersex traits self-identify as intersex, and some do not.[86][87] Australian sociological research published in 2016, found that 60% of respondents used the term "intersex" to self-describe their sex characteristics, including people identifying themselves as intersex, describing themselves as having an intersex variation or, in smaller numbers, having an intersex condition. A majority of 75% of survey respondents also self-described as male or female.[27] Respondents also commonly used diagnostic labels and referred to their sex chromosomes, with word choices depending on audience.[27][81] Research by the Lurie Children's Hospital, Chicago, and the AIS-DSD Support Group published in 2017 found that 80% of affected Support Group respondents "strongly liked, liked or felt neutral about intersex" as a term, while caregivers were less supportive.[88] The hospital reported that "disorders of sex development" may negatively affect care.[89]

Some intersex organizations reference "intersex people" and "intersex variations or traits"[90] while others use more medicalized language such as "people with intersex conditions",[91] or people "with intersex conditions or DSDs (differences of sex development)" and "children born with variations of sex anatomy".[92] In May 2016, Interact Advocates for Intersex Youth published a statement recognizing "increasing general understanding and acceptance of the term "intersex"".[93]

Hermaphrodite

A hermaphrodite is an organism that has both male and female reproductive organs. Until the mid-20th century, "hermaphrodite" was used synonymously with "intersex".[42] The distinctions "male pseudohermaphrodite", "female pseudohermaphrodite" and especially "true hermaphrodite"[94] are vestiges of outdated 19th-century thinking, reflecting histology (microscopic appearance) of the gonads.[95][96][97] Medical terminology has shifted not only due to concerns about language, but also a shift to understandings based on genetics.

Currently, hermaphroditism is not to be confused with intersex, as the former refers only to a specific phenotypical presentation of sex organs and the latter to more complex combination of phenotypical and genotypical presentation. Using "hermaphrodite" to refer to intersex individuals is considered to be stigmatizing and misleading.[98] Hermaphrodite is used for animal and vegetal species in which the possession of both ovaries and testes is either serial or concurrent, and for living organisms without such gonads but present binary form of reproduction, which is part of the typical life history of those species; intersex has come to be used when this is not the case.

Disorders of sex development

"Disorders of sex development" (DSD) is a contested term,[9][10] defined to include congenital conditions in which development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex is atypical. Members of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology adopted this term in their "Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders".[12][44] While it adopted the term, to open "many more doors", the now defunct Intersex Society of North America itself remarked that intersex is not a disorder.[99] Other intersex people, activists, supporters, and academics have contested the adoption of the terminology and its implied status as a "disorder", seeing this as offensive to intersex individuals who do not feel that there is something wrong with them, regard the DSD consensus paper as reinforcing the normativity of early surgical interventions, and criticizing the treatment protocols associated with the new taxonomy.[100]

Sociological research in Australia, published in 2016, found that 3% of respondents used the term "disorders of sex development" or "DSD" to define their sex characteristics, while 21% use the term when accessing medical services. In contrast, 60% used the term "intersex" in some form to self-describe their sex characteristics.[81] U.S. research by the Lurie Children's Hospital, Chicago, and the AIS-DSD Support Group published in 2017 found that "disorders of sex development" terminology may negatively affect care, give offence, and result in lower attendance at medical clinics.[89][88]

Alternatives to categorizing intersex conditions as "disorders" have been suggested, including "variations of sex development".[11] Organisation Intersex International (OII) questions a disease/disability approach, argues for deferral of intervention unless medically necessary, when fully informed consent of the individual involved is possible, and self-determination of sex/gender orientation and identity.[101] The UK Intersex Association is also highly critical of the label 'disorders' and points to the fact that there was minimal involvement of intersex representatives in the debate which led to the change in terminology.[102] In May 2016, Interact Advocates for Intersex Youth also published a statement opposing pathologizing language to describe people born with intersex traits, recognizing "increasing general understanding and acceptance of the term "intersex"".[93]

LGBT and LGBTI

Intersex can be contrasted with homosexuality or same-sex attraction. Numerous studies have shown higher rates of same sex attraction in intersex people,[103][104] with a recent Australian study of people born with atypical sex characteristics finding that 52% of respondents were non-heterosexual,[27][81] thus research on intersex subjects has been used to explore means of preventing homosexuality.[103][104] However, current studies do not support a statistical correlation between genetic intersex traits and transsexual persons.[105][106]

Intersex can therefore be contrasted with transgender,[107] which describes the condition in which one's gender identity does not match one's assigned sex.[107][108][109] Some people are both intersex and transgender.[110] A 2012 clinical review paper found that between 8.5% and 20% of people with intersex variations experienced gender dysphoria.[28] In an analysis of the use of preimplantation genetic diagnosis to eliminate intersex traits, Behrmann and Ravitsky state: "Parental choice against intersex may ... conceal biases against same-sex attractedness and gender nonconformity."[111]

The relationship of intersex to lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans, and queer communities is complex,[112] but intersex people are often added to LGBT to create an LGBTI community. Emi Koyama describes how inclusion of intersex in LGBTI can fail to address intersex-specific human rights issues, including creating false impressions "that intersex people's rights are protected" by laws protecting LGBT people, and failing to acknowledge that many intersex people are not LGBT.[113] Organisation Intersex International Australia states that some intersex individuals are same sex attracted, and some are heterosexual, but "LGBTI activism has fought for the rights of people who fall outside of expected binary sex and gender norms."[114][115] Julius Kaggwa of SIPD Uganda has written that, while the gay community "offers us a place of relative safety, it is also oblivious to our specific needs".[116] Mauro Cabral has written that transgender people and organizations "need to stop approaching intersex issues as if they were trans issues" including use of intersex as a means of explaining being transgender; "we can collaborate a lot with the intersex movement by making it clear how wrong that approach is".[117]

Intersex in society

Fiction and media

An intersex character is the narrator in Jeffrey Eugenides' Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Middlesex.

Television works about intersex and films about intersex are scarce. The Spanish-language film XXY won the Critics' Week grand prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival and the ACID/CCAS Support Award.[118] Faking It is notable for providing the first intersex main character in a television show,[119] and television's first intersex character played by an intersex actor.[120]

Civil society institutions

Intersex peer support and advocacy organizations have existed since at least 1985, with the establishment of the Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group Australia in 1985.[121] The Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group (UK) established in 1988.[122] The Intersex Society of North America (ISNA) may have been one of the first intersex civil society organizations to have been open to people regardless of diagnosis; it was active from 1993 to 2008.[123]

Events

Intersex Awareness Day is an internationally observed civil awareness day designed to highlight the challenges faced by intersex people, occurring annually on 26 October. It marks the first public demonstration by intersex people, which took place in Boston on October 26, 1996, outside a venue where the American Academy of Pediatrics was holding its annual conference.[124]

Intersex Day of Remembrance, also known as Intersex Solidarity Day, is an internationally observed civil awareness day designed to highlight issues faced by intersex people, occurring annually on 8 November. It marks the birthday of Herculine Barbin, a French intersex person whose memoirs were later published by Michel Foucault in Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite.

Flag

The intersex flag was created by Organisation Intersex International Australia in July 2013 to create a flag "that is not derivative, but is yet firmly grounded in meaning". The organization aimed to create a symbol without gendered pink and blue colors. It describes yellow and purple as "hermaphrodite" colors. The organization describes it as freely available "for use by any intersex person or organization who wishes to use it, in a human rights affirming community context".[125]

Religion

In Hinduism, Sangam literature uses the word pedi to refer to people born with an intersex condition; it also refers to antharlinga hijras and various other hijras.[126] Warne and Raza argue that an association between intersex and hijra people is mostly unfounded but provokes parental fear.[49]

In Islam, scholars of Islamic jurisprudence have detailed discussions on the status and rights of intersex based on what mainly exhibits in their external sexual organs. Yet, modern Islamic jurisprudence scholars turn to medical screening to determine the dominance of their sex. The intersex rights includes rights of inheritance, rights to marriage, rights to live like any other male or female. The rights are generally based on whether they are true hermaphrodites, or pseudo hermaphrodite. Scholars of Islamic jurisprudence generally consider their rights based on the majority of what appears from their external sexual organs.[citation needed]

In Judaism, the Talmud contains extensive discussion concerning the status of two intersex types in Jewish law; namely the androginus, which exhibits both male and female external sexual organs, and the tumtum which exhibits neither. In the 1970s and 1980s, the treatment of intersex babies started to be discussed in Orthodox Jewish medical halacha by prominent rabbinic leaders, for example Eliezer Waldenberg and Moshe Feinstein.[127]

Sport

Multiple athletes have been humiliated, excluded from competition or been forced to return medals following discovery of an intersex trait. Examples include Erik Schinegger, Foekje Dillema, Maria José Martínez-Patiño and Santhi Soundarajan. In contrast, Stanisława Walasiewicz (also known as Stella Walsh) was the subject of posthumous controversy.[128]

The South African middle-distance runner Caster Semenya won gold at the World Championships in the women's 800 meter and won silver in the 2012 Summer Olympics. When Semenya won gold in the World Championships, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) requested sex verification tests. The results were not released, but Semenya was cleared to race with other women.[129] Katrina Karkazis, Rebecca Jordan-Young, Georgiann Davis and Silvia Camporesi argued that new IAAF policies on "hyperandrogenism" in female athletes, established in response to the Semenya case, are "significantly flawed", arguing that the policy will not protect against breaches of privacy, will require athletes to undergo unnecessary treatment in order to compete, and will intensify "gender policing". They recommend that athletes be able to compete in accordance with their legal gender.[130]

In April 2014, the BMJ reported that four elite women athletes with 5-ARD were subjected to sterilization and "partial clitoridectomies" in order to compete in sport. The authors noted that "partial clitoridectomy" was "not medically indicated, does not relate to real or perceived athletic "advantage".[17] Intersex advocates regard this intervention as "a clearly coercive process".[131] In 2016, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on health, Dainius Pūras, criticized "current and historic" sex verification policies, describing how "a number of athletes have undergone gonadectomy (removal of reproductive organs) and partial clitoridectomy (a form of female genital mutilation) in the absence of symptoms or health issues warranting those procedures."[132]

Population figures

There are few firm estimates of the number of intersex people. While human rights institutions have called for the demedicalisation of intersex traits, as far as possible,[21][51][133][134] medical definitions are often still used. The now-defunct Intersex Society of North America stated that:

If you ask experts at medical centers how often a child is born so noticeably atypical in terms of genitalia that a specialist in sex differentiation is called in, the number comes out to about 1 in 1500 to 1 in 2000 births. But a lot more people than that are born with subtler forms of sex anatomy variations, some of which won’t show up until later in life.[135]

According to Blackless, Fausto-Sterling et al., 1.7 percent of human births are intersex, including variations that may not become apparent until, for example, puberty, or until attempting to conceive.[136][137] Some clinicians do not favor such definitions. According to Leonard Sax, intersex should be "restricted to those conditions in which chromosomal sex is inconsistent with phenotypic sex, or in which the phenotype is not classifiable as either male or female", around 0.018%. This definition excludes Klinefelter syndrome and many other variations.[138] He in turn criticizes Fausto-Sterling for counting Late-Onset Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia for 88% of her figure. His rebuttal concludes,

"The most original feature of Fausto-Sterling's book is her reluctance to classify true intersex conditions as pathological (Fausto-Sterling, 2000, p. 113) ... She often uses the word natural synonymously with normal. However, natural and normal are not synonyms. A cow may give birth to a two-headed or Siamese calf by natural processes, natural being understood as per Fausto-Sterling's definition as "produced by nature." Nevertheless, that two-headed calf unarguably manifests an abnormal condition. Fausto-Sterling's insistence that all combinations of sexual anatomy be regarded as normal... follows that classifications of normal and abnormal sexual anatomy are mere social conventions, prejudices which can and should be set aside by an enlightened intelligentsia. This type of extreme social constructionism is confusing and is not helpful to clinicians, to their patients, or to their patients' families. Diluting the term intersex to include "any deviation from the Platonic ideal of sexual dimorphism" (Blackless et al., 2000, p. 152), as Fausto-Sterling suggests, deprives the term of any clinically useful meaning."[139]

However, many conditions excluded from Sax's analysis are currently regarded as disorders of sex development. Individuals with those diagnoses may experience stigma and discrimination due to their sex characteristics, including sex "normalizing" interventions, and so those diagnoses and life experiences meet definitions of intersex in use by UN and other bodies. As a result, the statistical analyses by Blackless and Fausto-Sterling, despite her outdated and perceived offensive use of the term hermaphrodite,[140] have become widely quoted,[51][141] including by other clinicians.[142] The following summarizes those frequency statistics:

| Sex Variation | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Not XX, XY, Klinefelter, or Turner | one in 1,666 births |

| Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) | one in 1,000 births |

| Turner syndrome (45,X) | one in 2,710 births[143] |

| Androgen insensitivity syndrome | one in 13,000 births |

| Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome | one in 130,000 births |

| Classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia | one in 13,000 births |

| Late onset adrenal hyperplasia | one in 10,000 births.[144] |

| Vaginal agenesis | one in 6,000 births |

| Ovotestes | one in 83,000 births |

| Idiopathic (no discernable medical cause) | one in 110,000 births |

| Iatrogenic (caused by medical treatment, e.g. progestin administered to pregnant mother) | No estimate |

| 5-alpha-reductase deficiency | No estimate |

| Mixed gonadal dysgenesis | No estimate |

| MRKH Syndrome | 1 in 4,500-5,000 births |

| Complete gonadal dysgenesis | one in 150,000 births |

| Hypospadias (urethral opening in perineum or along penile shaft) | one in 250 births[145] |

| Epispadias (urethral opening between corona and tip of glans penis) | one in 117,000 births[146] |

Population figures can vary due to genetic causes. In the Dominican Republic, 5-alpha-reductase deficiency is not uncommon in the town of Las Salinas resulting in social acceptance of the intersex trait.[147] Men with the trait are called "guevedoces" (Spanish for "eggs at twelve"). 12 out of 13 families had one or more male family members that carried the gene. The overall incidence for the town was 1 in every 90 males were carriers, with other males either non-carriers or non-affected carriers.[148]

Medical classifications

Signs

Ambiguous genitalia

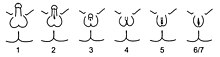

Ambiguous genitalia may appear as a large clitoris or as a small penis.

Because there is variation in all of the processes of the development of the sex organs, a child can be born with a sexual anatomy that is typically female or feminine in appearance with a larger-than-average clitoris (clitoral hypertrophy) or typically male or masculine in appearance with a smaller-than-average penis that is open along the underside. The appearance may be quite ambiguous, describable as female genitals with a very large clitoris and partially fused labia, or as male genitals with a very small penis, completely open along the midline ("hypospadic"), and empty scrotum. Fertility is variable.

Measurement systems

The Orchidometer is a medical instrument to measure the volume of the testicles. It was developed by Swiss pediatric endocrinologist Andrea Prader. The Prader scale[149] and Quigley scale are visual rating systems that measure genital appearance.

Other signs

In order to help in classification, methods other than a genitalia inspection can be performed. For instance, a karyotype display of a tissue sample may determine which of the causes of intersex is prevalent in the case.

Causes

The common pathway of sexual differentiation, where a productive human female has an XX chromosome pair, and a productive male has an XY pair, is relevant to the development of intersex conditions.

During fertilization, the sperm adds either an X (female) or a Y (male) chromosome to the X in the ovum. This determines the genetic sex of the embryo.[150] During the first weeks of development, genetic male and female fetuses are "anatomically indistinguishable", with primitive gonads beginning to develop during approximately the sixth week of gestation. The gonads, in a "bipotential state", may develop into either testes (the male gonads) or ovaries (the female gonads), depending on the consequent events.[150] Through the seventh week, genetically female and genetically male fetuses appear identical.

At around eight weeks of gestation, the gonads of an XY embryo differentiate into functional testes, secreting testosterone. Ovarian differentiation, for XX embryos, does not occur until approximately Week 12 of gestation. In normal female differentiation, the Müllerian duct system develops into the uterus, Fallopian tubes, and inner third of the vagina. In males, the Müllerian duct-inhibiting hormone MIH causes this duct system to regress. Next, androgens cause the development of the Wolffian duct system, which develops into the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and ejaculatory ducts.[150] By birth, the typical fetus has been completely "sexed" male or female, meaning that the genetic sex (XY-male or XX-female) corresponds with the phenotypical sex; that is to say, genetic sex corresponds with internal and external gonads, and external appearance of the genitals.

Conditions

There are a variety of opinions on what conditions or traits are and are not intersex, dependent on the definition of intersex that is used. Current human rights based definitions stress a broad diversity of sex characteristics that differ from expectations for male or female bodies.[2] During 2015, the Council of Europe,[51] the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights[133] and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights[134] have called for a review of medical classifications on the basis that they presently impede enjoyment of the right to health; the Council of Europe expressed concern that "the gap between the expectations of human rights organisations of intersex people and the development of medical classifications has possibly widened over the past decade".[51][133][134]

| List of conditions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex chromosomes | Name | Description |

| XX | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) | The most common cause of sexual ambiguity is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), an endocrine disorder in which the adrenal glands produce abnormally high levels of virilizing hormones in utero. The genes that cause CAH can now be detected in the developing embryo. As Fausto-Sterling mentioned in chapter 3 of Sexing the Body, "a woman who suspects she may be pregnant with a CAH baby (if she or someone in her family carries CAH) can undergo treatment and then get tested." To prevent an XX-CAH child's genitalia from becoming masculinized, a treatment, which includes the use of the steroid dexamethasone, must begin as early as four weeks after formation. Many do not favor this process because "the safety of this experimental therapy has not been established in rigorously controlled trials", it does allow physicians to detect abnormalities, therefore starting treatment right after birth. Starting treatment as soon as an XX-CAH baby is born not only minimizes, but also may even eliminate the chances of genital surgery from being performed.[137] However the necessity of such surgery itself is disputed.

Meta-analysis of the studies supporting the use of dexamethasone on CAH at-risk fetuses found "less than one half of one percent of published 'studies' of this intervention were regarded as being of high enough quality to provide meaningful data for a meta-analysis. Even these four studies were of low quality" ... "in ways so slipshod as to breach professional standards of medical ethics"[151] and "there were no data on long-term follow-up of physical and metabolic outcomes in children exposed to dexamethasone".[152] In XX-females, this can range from partial masculinization that produces a large clitoris, to virilization and male appearance. The latter applies in particular to Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency, which is the most common form of CAH. Individuals born with XX chromosomes affected by 17α-hydroxylase deficiency are born with female internal and external anatomy, but, at puberty, neither the adrenals nor the ovaries can produce sex-hormones, inhibiting breast development and the growth of pubic hair. See below for XY CAH 17α-hydroxylase deficiency. |

| XX | Progestin-induced virilisation | In this case, the excess androgen hormones are caused by use of progestin, a drug that was used in the 1950s and 1960s to prevent miscarriage. These individuals normally have internal and external female anatomy, with functional ovaries and will therefore have menstruation. They develop, however, some male secondary sex characteristics and they frequently have unusually large clitorises. In very advanced cases, such children have initially been identified as males.[153] |

| XX | Freemartinism | This condition occurs commonly in all species of cattle and affects most females born as a twin to a male. It is rare or unknown in other mammals, including humans. In cattle, the placentae of fraternal twins usually fuse at some time during the pregnancy, and the twins then share their blood supply. If the twins are of different sexes, male hormones produced in the body of the fetal bull find their way into the body of the fetal heifer (female), and masculinize her. Her sexual organs do not develop fully, and her ovaries may even contain testicular tissue. When adult, such a freemartin is very like a normal female in external appearance, but she is infertile, and behaves more like a castrated male (a steer). The male twin is not significantly affected, although (if he remains entire) his testes may be slightly reduced in size. The degree of masculinization of the freemartin depends on the stage of pregnancy at which the placental fusion occurs – in about ten percent of such births no fusion occurs and both calves develop normally as in other mammals. |

| XY | Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) | People with AIS have a Y chromosome, (typically XY), but are unable to metabolize androgens in varying degrees.

Cases with typically female appearance and genitalia are said to have complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS). People with CAIS have a vagina and no uterus, cervix, or ovaries, and are infertile. The vagina may be shorter than usual, and, in some cases, is nearly absent. Instead of female internal reproductive organs, a person with CAIS has undescended or partially descended testes, of which the person may not even be aware. In mild and partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (MAIS and PAIS), the body is partially receptive to androgens, so there is virilization to varying degrees. PAIS can result in genital ambiguity, due to limited metabolization of the androgens produced by the testes. Ambiguous genitalia may present as a large clitoris, known as clitoromegaly, or a small penis, which is called micropenis or microphallus; hypospadias and cryptorchidism may also be present, with one or both testes undescended, and hypospadias appearing just below the glans on an otherwise typical male penis, or at the base of the shaft, or at the perineum and including a bifid (or cleft) scrotum. |

| XY | 5-alpha-reductase deficiency (5-ARD) | The condition affects individuals with a Y chromosome, making their bodies unable to convert testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT is necessary for the development of male genitalia in utero, and plays no role in female development, so its absence tends to result in ambiguous genitalia at birth; the effects can range from infertility with male genitalia to male underdevelopment with hypospadias to female genitalia with mild clitoromegaly. The frequency is unknown, and children are sometimes misdiagnosed as having AIS.[154] Individuals can have testes, as well as vagina and labia, and a small penis capable of ejaculation that looks like a clitoris at birth. Such individuals are usually raised as girls. The lack of DHT also limits the development of facial hair. |

| XY | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) | In individuals with a Y chromosome (typically XY) who have Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 17 alpha-hydroxylase deficiency, CAH inhibits virilization, unlike cases without a Y chromosome. |

| XY | Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS) | The child has XY chromosomes typical of a male. The child has a male body and an internal uterus and fallopian tubes because his body did not produce Müllerian inhibiting factor during fetal development. |

| XY | Anorchia | Individuals with XY chromosomes whose gonads were lost after 14 weeks of fetal development. People with Anorchia have no ability to produce the hormones responsible for developing male secondary sex characteristics nor the means to produce gametes necessary for reproduction due to the lack of gonads. They may develop typically feminine secondary sex characteristics without or despite the administration of androgens to artificially initiate physical sex differentiation (typically planned around the age of puberty). Psychological and neurological gender identity may solidify before the administration of androgens, leading to gender dysphoria, as anorchic individuals are typically assigned male at birth. |

| XY | Gonadal Dysgenesis | It has various causes and are not all genetic; a catch-all category. It refers to individuals (mostly XY) whose gonads don't develop properly. Clinical features are heterogeneous.[137] |

| XY | Hypospadias | It is caused by various causes, including alterations in testosterone metabolism. The urethra does not run to the tip of the penis. In mild forms, the opening is just shy of the tip; in moderate forms, it is along the shaft; and in severe forms, it may open at the base of the penis.[155] |

| Other | Unusual chromosomal sex | In addition to the most common XX and XY chromosomal sexes, there are several other possible combinations, for example Turner syndrome (XO), Triple X syndrome (XXX), Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) and variants (XXYY, XXXY, XXXXY), XYY syndrome, de la Chapelle syndrome (XX male), Swyer syndrome (XY female). |

| Other | Mosaicism and chimerism | A mix can occur, where some of the cells of the body have the common XX or XY, while some have one of the less usual chromosomal contents above. Such a mixture is caused by either mosaicism or chimerism. In mosaicism, the mixture is caused by a mutation in one of the cells of the embryo after fertilization, whereas chimerism is a fusion of two embryos.

In alternative fashion, it is simply a mixture between XX and XY, and does not have to involve any less-common genotypes in individual cells. This, too, can occur both as chimerism and as a result of one sex chromosome having mutated into the other.[156] Mosaicism and chimerism may involve chromosomes other than the sex chromosomes, and not result in intersex traits. |

| Other | True hermaphroditism and ovotestis | A "true hermaphrodite" is defined as someone with both testicular and ovarian tissue. Though naturally occurring true hermaphroditism in humans is unknown, there is, on the other hand, a spectrum of forms of ovotestes. The varieties include having two ovotestes or one ovary and one ovotestis, often in the form of streak gonads. Phenotype is not determinable from the ovotestes; in some cases, the appearance is "fairly typically female"; in others, it is "fairly typically male", and it may also be "fairly in-between in terms of genital development."[157] Intersex activist Cheryl Chase is an example of someone with ovotestes.[158] |

Medical interventions

Rationales

Medical interventions take place to address physical health concerns, and psychosocial risks. Both types of rationale are the subject of debate, particularly as the consequences of surgical (and many hormonal) interventions are lifelong and irreversible. Questions regarding physical health include accurately assessing risk levels, necessity and timing. Psychosocial rationales are particularly susceptible to questions of necessity as they reflect social and cultural concerns.

There remains no clinical consensus about an evidence base, surgical timing, necessity, type of surgical intervention, and degree of difference warranting intervention.[159][160][161] Such surgeries are the subject of significant contention due to consequences that include trauma, impact on sexual function and sensation, and violation of rights to physical and mental integrity.[1] This includes community activism,[40] and multiple reports by international human rights[19][51][23][162] and health[72] institutions and national ethics bodies.[22][163]

In the cases where gonads may pose a cancer risk, as in some cases of androgen insensitivity syndrome,[164] concern has been expressed that treatment rationales and decision-making regarding cancer risk may encapsulate decisions around a desire for surgical normalization.[21]

Types

- Feminizing and masculinizing surgeries: Surgical procedures depend on diagnosis, and there is often concern as to whether surgery should be performed at all. Typically, surgery is performed shortly after birth. Defenders of the practice argue that it is necessary for individuals to be clearly identified as male or female in order for them to function socially and develop normally. Psychosocial reasons are often stated.[12] This is criticised by many human rights institutions, and authors. Unlike other aesthetic surgical procedures performed on infants, such as corrective surgery for a cleft lip, genital surgery may lead to negative consequences for sexual functioning in later life, or feelings of freakishness and unacceptability.[165]

- Hormone treatment: There is widespread evidence of prenatal testing and hormone treatment to prevent or eliminate intersex traits,[166][167] associated also with the problematization of sexual orientation and gender non-conformity.[166][168]

- Psychosocial support: All stakeholders support psychosocial support. A joint international statement by participants at the Third International Intersex Forum in 2013 sought, amongst other demands: "Recognition that medicalization and stigmatisation of intersex people result in significant trauma and mental health concerns. In view of ensuring the bodily integrity and well-being of intersex people, autonomous non-pathologising psycho-social and peer support be available to intersex people throughout their life (as self-required), as well as to parents and/or care providers."

- Genetic selection and terminations: The ethics of preimplantation genetic diagnosis to select against intersex traits was the subject of 11 papers in the October 2013 issue of the American Journal of Bioethics.[169] There is widespread evidence of pregnancy terminations arising from prenatal testing, as well as prenatal hormone treatment to prevent intersex traits. Behrmann and Ravitsky find social concepts of sex, gender and sexual orientation to be "intertwined on many levels. Parental choice against intersex may thus conceal biases against same-sex attractedness and gender nonconformity."[111]

- Gender dysphoria: The DSM-5 included a change from using Gender Identity Disorder to Gender Dysphoria. This revised code now specifically includes intersex people who do not identify with their sex assigned at birth, using the language of Disorders of Sex Development.[170] This move was criticised by intersex advocacy groups in Australia and New Zealand.[170]

- Medical photography and display: Photographs of intersex children's genitalia are circulated in medical communities for documentary purposes. Problems associated with medical photography of intersex children have been discussed due to experiences of humiliation and powerlessness by child subjects,[171] along with their ethics, control and usage.[172]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e UN Committee against Torture; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child; UN Committee on the Rights of People with Disabilities; UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; Juan Méndez, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; Dainius Pῡras, Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; Dubravka Šimonoviæ, Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences; Marta Santos Pais, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Violence against Children; African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights; Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (24 October 2016), "Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October. End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge", Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex" (PDF). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b Money, John; Ehrhardt, Anke A. (1972). Man & Woman Boy & Girl. Differentiation and dimorphism of gender identity from conception to maturity. USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-1405-7.

- ^ a b c d Domurat Dreger, Alice (2001). Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex. USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00189-3.

- ^ Mason, H.J., Favorinus’ Disorder: Reifenstein’s Syndrome in Antiquity?, in Janus 66 (1978) 1–13.

- ^ Nguyễn Khắc Thuần (1998), Việt sử giai thoại (History of Vietnam's tales), vol. 8, Vietnam Education Publishing House, p. 55

- ^ Richardson, Ian D. (May 2012). God's Triangle. Preddon Lee Limited. ISBN 9780957140103.

- ^ Dreger, Alice D.; Chase, Cheryl; Sousa, Aron; Gruppuso, Phillip A.; Frader, Joel (18 August 2005). ""Changing the Nomenclature/Taxonomy for Intersex: A Scientific and Clinical Rationale."" (PDF). Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b Davis, Georgiann (11 September 2015). Contesting Intersex: The Dubious Diagnosis. New York University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-1479887040.

- ^ a b Holmes, Morgan (September 2011). "The Intersex Enchiridion: Naming and Knowledge". Somatechnics. 1 (2): 388–411. doi:10.3366/soma.2011.0026. ISSN 2044-0138. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ a b Diamond M, Beh HG (27 July 2006). Variations of Sex Development Instead of Disorders of Sex Development. Arch Dis Child

- ^ a b c Houk, C. P.; Hughes, I. A.; Ahmed, S. F.; Lee, P. A.; Writing Committee for the International Intersex Consensus Conference Participants (August 2006). "Summary of Consensus Statement on Intersex Disorders and Their Management". Pediatrics. 118 (2): 753–757. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0737. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 16882833.

- ^ a b c Civil Society Coalition on Human Rights and Constitutional Law; Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum; Rainbow Health Foundation; Sexual Minorities Uganda; Support Initiative for Persons with Congenital Disorders (2014). "Uganda Report of Violations based on Sex Determination, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation".

- ^ a b Grady, Helen; Soy, Anne (4 May 2017). "The midwife who saved intersex babies". BBC World Service, Kenya.

- ^ a b Beyond the Boundary - Knowing and Concerns Intersex (October 2015). "Intersex report from Hong Kong China, and for the UN Committee Against Torture: the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment".

- ^ Submission 88 to the Australian Senate inquiry on the involuntary or coerced sterilisation of people with disabilities in Australia, Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group (APEG), 27 June 2013

- ^ a b Jordan-Young, R. M.; Sonksen, P. H.; Karkazis, K. (April 2014). "Sex, health, and athletes". BMJ. 348 (apr28 9): –2926–g2926. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2926. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 24776640. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Macur, Juliet (6 October 2014). "Fighting for the Body She Was Born With". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ a b Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, February 2013.

- ^ Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization, An interagency statement, World Health Organization, May 2014.

- ^ a b c d Senate of Australia; Community Affairs References Committee (2013). Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia. Canberra. ISBN 978-1-74229-917-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics NEK-CNE (November 2012). On the management of differences of sex development. Ethical issues relating to "intersexuality".Opinion No. 20/2012 (PDF). 2012. Berne.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions (June 2016). Promoting and Protecting Human Rights in relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Sex Characteristics. ISBN 978-0-9942513-7-4.

- ^ a b c International Commission of Jurists. "In re Völling, Regional Court Cologne, Germany (6 February 2008)". Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d Reuters (1 April 2015). "Surgery and Sterilization Scrapped in Malta's Benchmark LGBTI Law". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d Star Observer (2 April 2015). "Malta passes law outlawing forced surgical intervention on intersex minors". Star Observer.

- ^ a b c d e "New publication "Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia"". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 3 February 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Furtado P. S.; et al. (2012). "Gender dysphoria associated with disorders of sex development". Nat. Rev. Urol. 9 (11): 620–627. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2012.182. PMID 23045263.

- ^ a b Marañón, Gregorio (1929). Los estados intersexuales en la especie humana. Madrid: Morata.

- ^ Knox, David; Schacht, Caroline. (2010) Choices in Relationships: An Introduction to Marriage and the Family. 11 ed. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781111833220. p. 64.

- ^ "What is intersex?". Intersex Society of North America. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus (1935). Library of History (Book IV). Loeb Classical Library Volumes 303 and 340. C H Oldfather (trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Lynn E. Roller, "The Ideology of the Eunuch Priest," Gender & History 9.3 (1997), p. 558.

- ^ Decretum Gratiani, C. 4, q. 2 et 3, c. 3

- ^ "Decretum Gratiani (Kirchenrechtssammlung)". Bayerische StaatsBibliothek (Bavarian State Library). 5 February 2009.

- ^ Raming, Ida; Macy, Gary; Bernard J, Cook (2004). A History of Women and Ordination. Scarecrow Press. p. 113.

- ^ E Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England, Institutes 8.a. (1st Am. Ed. 1812) (16th European ed. 1812).

- ^ Greenberg, Julie (1999). "Defining Male and Female: Intersexuality and the Collision Between Law and Biology". Arizona Law Review. 41: 277–278. SSRN 896307.

- ^ Holmes, Morgan (July 2004). "Locating Third Sexes". Transformations Journal (8). ISSN 1444-3775. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ a b Intersex Issues in the International Classification of Diseases: a revision (PDF). Mauro Cabral, Morgan Carpenter (eds.). 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Goldschmidt, R. (1917), "Intersexuality and the endocrine aspect of sex", Endocrinology, 1 (4): 433–456, doi:10.1210/endo-1-4-433.

- ^ a b Cawadias, A. P. (1943) Hermaphoditus the Human Intersex, London, Heinemann Medical Books Ltd.

- ^ Coran, Arnold G.; Polley, Theodore Z. (July 1991). "Surgical management of ambiguous genitalia in the infant and child". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 26 (7): 812–820. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(91)90146-K. PMID 1895191.

- ^ a b Hughes, I A; Houk, C; Ahmed, S F; Lee, P A; LWPES1/ESPE2 Consensus Group (June 2005). "Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (7): 554–563. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.098319. ISSN 0003-9888. PMC 2082839. PMID 16624884.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Dreger, Alice Domurat (May 1998). ""Ambiguous Sex"--or Ambivalent Medicine?". The Hastings Center Report. 28 (3): 24–35. doi:10.2307/3528648.

- ^ Dreger, Alice (3 April 2015). "Malta Bans Surgery on Intersex Children". The Stranger SLOG.

- ^ Public statement by the third international intersex forum. Malta. 2 December 2013.

- ^ Odero, Joseph (23 December 2015). "Intersex in Kenya: Held captive, beaten, hacked. Dead". 76 CRIMES. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ a b Warne, Garry L.; Raza, Jamal (September 2008). "Disorders of sex development (DSDs), their presentation and management in different cultures". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 9 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1007/s11154-008-9084-2. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 18633712. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Ghattas, Dan Christian; Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (2013). Human Rights between the Sexes A preliminary study on the life situations of inter*individuals (PDF). Berlin: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. ISBN 978-3-86928-107-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Council of Europe; Commissioner for Human Rights (April 2015), Human rights and intersex people, Issue Paper

- ^ Curtis, Skyler (2010–2011). "Reproductive Organs and Differences of Sex Development: The Constitutional Issues Created by the Surgical Treatment of Intersex Children". McGeorge Law Review. 42: 863. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Corte Constitucional de Colombia: Sentencia T-1025/02". Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. "United Nations for Intersex Awareness". Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Government Gazette, Republic of South Africa, Vol. 487, Cape Town, 11 January 2006.

- ^ Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013, No. 98, 2013, ComLaw, C2013A00098, 2013.

- ^ On the historic passing of the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013, Organisation Intersex International Australia, 25 June 2013.

- ^ Malta (April 2015), Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act: Final version

- ^ Cabral, Mauro (8 April 2015). "Making depathologization a matter of law. A comment from GATE on the Maltese Act on Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics". Global Action for Trans Equality. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ OII Europe (1 April 2015). "OII-Europe applauds Malta's Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act. This is a landmark case for intersex rights within European law reform". Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan (2 April 2015). "We celebrate Maltese protections for intersex people". Organisation Intersex International Australia. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Transgender Europe (1 April 2015). Malta Adopts Ground-breaking Trans and Intersex Law – TGEU Press Release.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht (12 August 2009). "Christiane Völling: Hermaphrodite wins damage claim over removal of reproductive organs". Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ "Condenan al H. de Talca por error al determinar sexo de bebé". diario.latercera.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ García, Gabriela. "Identidad forzada". www.paula.cl (in Spanish).

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht (17 December 2015). "Nuremberg Hermaphrodite Lawsuit: Michaela "Micha" Raab Wins Damages and Compensation for Intersex Genital Mutilations!". Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Southern Poverty Law Centre (14 May 2013). "Groundbreaking SLPC Lawsuit Accuses South Carolina Doctors and Hospitals of Unnecessary Surgery on Infant". Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Dreger, Alice (16 May 2013). "When to Do Surgery on a Child With 'Both' Genitalia". The Atlantic. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Holmes, Morgan. "Is Growing up in Silence Better Than Growing up Different?". Intersex Society of North America.

- ^ Intersex Society of North America. "What's wrong with the way intersex has traditionally been treated?".

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan (3 February 2015). Intersex and ageing. Organisation Intersex International Australia.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2015). Sexual health, human rights and the law. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241564984.

- ^ "Kenya takes step toward recognizing intersex people in landmark ruling". Reuters.

- ^ "Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender, 30 May 2013". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Holme, Ingrid (2008). "Hearing People's Own Stories". Science as Culture. 17 (3): 341–344. doi:10.1080/09505430802280784. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "New Zealand Passports - Information about Changing Sex / Gender Identity". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Third sex option on birth certificates, Deutsche Welle, 1 November 2013.

- ^ "Intersex: Third Gender in Germany" (Spiegel, Huff Post, Guardian, ...): Silly Season Fantasies vs. Reality of Genital Mutilations, Zwischengeschlecht, 1 November 2013

- ^ Sham package for Intersex: Leaving sex entry open is not an option, OII Europe, 15 February 2013

- ^ ‘X’ gender: Germans no longer have to classify their kids as male or female, RT, 3 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Tiffany; Hart, Bonnie; Carpenter, Morgan; Ansara, Gavi; Leonard, William; Lucke, Jayne (2016). Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-208-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Zderic, Stephen (2002). Pediatric gender assignment : a critical reappraisal ; [proceedings from a conference ... in Dallas in the spring of 1999 which was entitled "pediatric gender assignment - a critical reappraisal"]. New York, NY [u.a.]: Kluwer Acad. / Plenum Publ. ISBN 0306467593.

- ^ Frader, J.; Alderson, P.; Asch, A.; Aspinall, C.; Davis, D.; Dreger, A.; Edwards, J.; Feder, E. K.; Frank, A.; Hedley, L. A.; Kittay, E.; Marsh, J.; Miller, P. S.; Mouradian, W.; Nelson, H.; Parens, E. (May 2004). "Health care professionals and intersex conditions". Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 158 (5): 426–8. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.5.426. PMID 15123472.

- ^ Wiesemann, Claudia; Ude-Koeller, Susanne; Sinnecker, Gernot H. G.; Thyen, Ute (20 October 2009). "Ethical principles and recommendations for the medical management of differences of sex development (DSD)/intersex in children and adolescents" (PDF). European Journal of Pediatrics. 169 (6): 671–679. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-1086-x. PMC 2859219. PMID 19841941. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Diamond, Milton; H. Keith Sigmundson (1997). "Management of intersexuality: Guidelines for dealing with individuals with ambiguous genitalia". Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. June. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ Sharon Preves, "Intersex and Identity, the Contested Self". Rutgers, 2003.

- ^ Catherine Harper, "Intersex". Berg, 2007.

- ^ a b Johnson, Emilie K.; Rosoklija, Ilina; Finlayso, Courtney; Chen, Diane; Yerkes, Elizabeth B.; Madonna, Mary Beth; Holl, Jane L.; Baratz, Arlene B.; Davis, Georgiann; Cheng, Earl Y. (May 2017). "Attitudes towards "disorders of sex development" nomenclature among affected individuals". Journal of Pediatric Urology. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.03.035. ISSN 1477-5131.

- ^ a b Newswise (11 May 2017). "Term "Disorders of Sex Development" May Have Negative Impact". Newswise. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ Welcome to OII Australia – we promote human rights and bodily autonomy for intersex people, and provide information, education and peer support, Organisation Intersex International Australia, 4 April 2004

- ^ Answers to Your Questions About Individuals With Intersex Conditions, American Psychological Association, 2006.

- ^ Advocates for Informed Choice, Advocates for Informed Choice, undated, retrieved 19 September 2014

- ^ a b interACT (May 2016). "interACT Statement on Intersex Terminology". Interact Advocates for Intersex Youth. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ Molina B Dayal, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Fertility and IVF Center, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Medical Faculty Associates, George Washington University distingquishes what 'true hermaphroditism' encompasses in their study of Ovotestis. Found here: http://www.emedicine.com/med/TOPIC1702.HTM

- ^ W. S. Alexander M.D., O. D. Beresford M.D., M.R.C.P. (1953) wrote about extensively about 'female pseudohermaphrodite' origins in utera, in his paper "Masculinization of Ovarian Origin, published An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Volume 60 Issue 2 pp. 252–258, April 1953.

- ^ Am J Psychiatry 164:1499–1505, October 2007: Noted Mayo Clinic researchers J.M. Bostwick, MD, and Kari A Martin MD in A Man's Brain in an Ambiguous Body: A Case of Mistaken Gender wrote of the distinctions in male pseudohermaphrodite condition.

- ^ Langman, Jan; Thomas Sadler (2006). Langman's medical embryology. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 252. ISBN 0-7817-9485-4.

- ^ "Is a person who is intersex a hermaphrodite? | Intersex Society of North America". Isna.org. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ Intersex Society of North America (24 May 2006). Why is ISNA using "DSD"?. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ Feder, E. (2009) 'Imperatives of Normality: From "Intersex" to "Disorders of Sex Development".' A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies (GLQ), 15, 225–247.

- ^ Briffa, Tony (8 May 2014), Tony Briffa writes on "Disorders of Sex Development", Organisation Intersex International Australia

- ^ "Why Not "Disorders of Sex Development"?". UK Intersex Association. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ a b Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F.L. (January 1990). "Will Prenatal Hormone Treatment Prevent Homosexuality?". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 1 (4): 279–283. doi:10.1089/cap.1990.1.279. ISSN 1044-5463. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

human studies of the effects of altering the prenatal hormonal milieu by the administration of exogenous hormones lend support to a prenatal hormone theory that implicates both androgens and estrogens in the development of gender preference ... it is likely that prenatal hormone variations may be only one among several factors influencing the development of sexual orientation

- ^ a b Dreger, Alice; Feder, Ellen K; Tamar-Mattis, Anne (29 June 2010), Preventing Homosexuality (and Uppity Women) in the Womb?, The Hastings Center Bioethics Forum, retrieved 18 May 2016

- ^ Lombardo F et al. (Sep 2013). "Hormone and genetic study in male to female transsexual patients" J Endocrinol Invest. 36 (8) : 550-7. PMID 23324476. doi:10.3275/8813. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ Inoubli A et al. (Feb 2011). "Karyotyping, is it worthwhile in transsexualism?" J Sex Med. 8 (2) : 475-8. PMID 21114769. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02130.x. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b Children's right to physical integrity, Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly, Report Doc. 13297, 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Trans? Intersex? Explained!". Inter/Act. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Basic differences between intersex and trans". Organisation Intersex International Australia. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Cabral Grinspan, Mauro (25 October 2015), The marks on our bodies, Intersex Day

- ^ a b Behrmann, Jason; Ravitsky, Vardit (October 2013). "Queer Liberation, Not Elimination: Why Selecting Against Intersex is Not "Straight" Forward". The American Journal of Bioethics. 13 (10): 39–41. doi:10.1080/15265161.2013.828131. ISSN 1526-5161. PMID 24024805. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Dreger, Alice (4 May 2015). "Reasons to Add and Reasons NOT to Add "I" (Intersex) to LGBT in Healthcare" (PDF). Association of American Medical Colleges. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Koyama, Emi. "Adding the "I": Does Intersex Belong in the LGBT Movement?". Intersex Initiative. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Intersex for allies". 21 November 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ OII releases new resource on intersex issues, Intersex for allies and Making services intersex inclusive by Organisation Intersex International Australia, via Gay News Network, 2 June 2014.

- ^ Kaggwa, Julius (19 September 2016). "I'm an intersex Ugandan – life has never felt more dangerous". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ Cabral, Mauro (26 October 2016). "IAD2016: A Message from Mauro Cabral". GATE - Global Action for Trans Equality. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Leffler, Rebecca (26 May 2007). "Critics Week grand prize to 'XXY'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Meet television's groundbreaking intersex character". Buzzfeed.

- ^ ""Faking It" Breaks New Ground With First Intersex Actor To Play Intersex Character On TV". New Now Next. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group Australia; Briffa, Anthony (22 January 2003). "Discrimination against People affected by Intersex Conditions: Submission to NSW Government" (PDF). Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group (AISSG)". Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Dear ISNA Friends and Supporters". 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Holmes, Morgan (17 October 2015). "When Max Beck and Morgan Holmes went to Boston". Intersex Day. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ An intersex flag, Organisation Intersex International Australia, 5 July 2013

- ^ Winter, Gopi Shankar (2014). Maraikkappatta Pakkangal: மறைக்கப்பட்ட பக்கங்கள். Srishti Madurai. ISBN 9781500380939. OCLC 703235508.

- ^ "the space between - Stanford prof: Talmudic rabbis were into analyzing sexuality - j. the Jewish news weekly of Northern California". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Klaudia Snochowska-Gonzales. "Walasiewicz była kobietą (Walasiewicz Was a Woman)". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). 190 (14 August 2004): 8. Retrieved 31 May 2006.

- ^ Cooky, Cheryl; Shari L. Dworkin (February 2013). "Policing the Boundaries of Sex: A Critical Examination of Gender Verification and the Caster Semenya Controversy". Journal of Sex Research. 50 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.725488. PMID 23320629.

- ^ Karkazis, Katrina; Jordan-Young, Rebecca; Davis, Georgiann; Camporesi, Silvia (July 2012). "Out of Bounds? A Critique of the New Policies on Hyperandrogenism in Elite Female Athletes". The American Journal of Bioethics. 12 (7): 3–16. doi:10.1080/15265161.2012.680533. ISSN 1526-5161. PMC 5152729. PMID 22694023. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ "UN Human Rights Council: resolution, statement and side event, "The time has come"". Organisation Intersex International Australia. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Pūras, Dainius; Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (4 April 2016), Sport and healthy lifestyles and the right to health. Report A/HRC/32/33, United Nations

- ^ a b c European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (April 2015), The fundamental rights situation of intersex people (PDF)

- ^ a b c Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (12 November 2015), Violencia contra Personas Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Trans e Intersex en América (PDF) (in Spanish), Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos

- ^ "How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America". Isna.org. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Blackless, Melanie; Charuvastra, Anthony; Derryck, Amanda; Fausto-Sterling, Anne; Lauzanne, Karl; Lee, Ellen (March 2000). "How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis". American Journal of Human Biology. 12 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(200003/04)12:2<151::AID-AJHB1>3.0.CO;2-F. ISSN 1520-6300. PMID 11534012.

- ^ a b c Fausto-Sterling, Anne (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. Basic Books. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-465-07714-4.

- ^ Sax, Leonard (2002). "How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling". Journal of Sex Research. 39 (3): 174–178. doi:10.1080/00224490209552139. PMID 12476264.

- ^ http://homes.chass.utoronto.ca/~sousa/teach/PHL243-06.MAIN_files/20065_phl243h1f_archive/SAX-on-Intersex.pdf

- ^ http://www.fd.unl.pt/docentes_docs/ma/TPB_MA_5937.pdf

- ^ "On the number of intersex people". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Chaleyer, Rani (10 March 2015). "Intersex: the 'I' in 'LGBTI'". Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Per Fausto-Sterling. Donaldson et al. (2006) estimate one in 2,000 births and Marino (2013) estimates 1 in 5,000; see Turner syndrome.

- ^ Speiser, Phyllis W.; Azziz, Ricardo; Baskin, Laurence S.; Ghizzoni, Lucia; Hensle, Terry W.; Merke, Deborah P.; Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F. L.; Miller, Walter L.; Montori, Victor M.; Oberfield, Sharon E.; Ritzen, Martin; White, Perrin C. (2010). "Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to Steroid 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 95 (9). Endocrine Society: 4133–4160. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2631. PMC 2936060. PMID 20823466.

Nonclassic forms of CAH are more prevalent, occurring in approximately 0.1–0.2% in the general Caucasian population but in up to 1–2% among inbred populations, such as Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jews

- ^ Snodgrass, Warren (2012). "Chapter 130: Hypospadias". In Wein, Allan (ed.). Campbell-Walsh Urology, Tenth Edition. Elsevier. pp. 3503–3536. ISBN 978-1-4160-6911-9.

- ^ Epispadias, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Mosley, Michael. "The extraordinary case of the Guevedoces". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Imperato-McGinley, Julianne; Guerrero, Luis; Gautier, Teofilo; Peterson, Ralph Edward (December 1974). "Steroid 5alpha-reductase deficiency in man: an inherited form of male pseudohermaphroditism". Science. 186 (4170): 1213–1215. doi:10.1126/science.186.4170.1213. PMID 4432067.

- ^ Diamond, Milton; Linda, Watson (2004). "Androgen insensitivity syndrome and Klinefelter's syndrome: sex and gender considerations". Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. No. 13. pp. 623–640.

- ^ a b c Kolodny, Robert C.; Masters, William H.; Johnson, Virginia E. (1979). Textbook of Sexual Medicine (1st ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-50154-9.

- ^ Dreger, Alice; Ellen K. Feder; Anne Tamar-Mattis (30 July 2012). "Prenatal Dexamethasone for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia". Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 9 (3): 277–294. doi:10.1007/s11673-012-9384-9. PMC 3416978. PMID 22904609.

- ^ Fernández-Balsells, M.M.; K. Muthusamy; G. Smushkin; et al. (2010). "Prenatal dexamethasone use for the prevention of virilization in pregnancies at risk for classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia because of 21-hydroxylase (CYP21A2) deficiency: A systematic review and meta-analyses". Clinical Endocrinology. 73 (4): 436–444. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03826.x. PMID 20550539.

- ^ "2000 Intersex Society of North America – What is Progestin Induced Virilisation?". Healthyplace.com. 9 August 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ "eMedicine article on 5-ARD". Emedicine.com. 23 June 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Anne Fausto-Sterling 2000was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ De Marchi M, Carbonara AO, Carozzi F, et al. (1976). "True hermaphroditism with XX/XY sex chromosome mosaicism: report of a case". Clin. Genet. 10 (5): 265–72. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1976.tb00047.x. PMID 991437.

- ^ "ovo-testes (formerly called "true hermaphroditism")". Intersex Society of North America. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Weil, Elizabeth (September 2006). What if It's (Sort of) a Boy and (Sort of) a Girl? The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ Lee, Peter A.; Nordenström, Anna; Houk, Christopher P.; Ahmed, S. Faisal; Auchus, Richard; Baratz, Arlene; Baratz Dalke, Katharine; Liao, Lih-Mei; Lin-Su, Karen; Looijenga, Leendert H.J.; Mazur, Tom; Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F.L.; Mouriquand, Pierre; Quigley, Charmian A.; Sandberg, David E.; Vilain, Eric; Witchel, Selma; and the Global DSD Update Consortium (28 January 2016). "Global Disorders of Sex Development Update since 2006: Perceptions, Approach and Care". Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 85 (3): 158–180. doi:10.1159/000442975. ISSN 1663-2818. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Mouriquand, Pierre D. E.; Gorduza, Daniela Brindusa; Gay, Claire-Lise; Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F. L.; Baker, Linda; Baskin, Laurence S.; Bouvattier, Claire; Braga, Luis H.; Caldamone, Anthony C.; Duranteau, Lise; El Ghoneimi, Alaa; Hensle, Terry W.; Hoebeke, Piet; Kaefer, Martin; Kalfa, Nicolas; Kolon, Thomas F.; Manzoni, Gianantonio; Mure, Pierre-Yves; Nordenskjöld, Agneta; Pippi Salle, J. L.; Poppas, Dix Phillip; Ransley, Philip G.; Rink, Richard C.; Rodrigo, Romao; Sann, Léon; Schober, Justine; Sibai, Hisham; Wisniewski, Amy; Wolffenbuttel, Katja P.; Lee, Peter. "Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: If (why), when, and how?". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 12: 139–149. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.001. ISSN 1477-5131. Retrieved 30 May 2016.