Centaur

Centauress, by John La Farge | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Hybrid |

| Other name(s) | Kentaur, Κένταυρος, Centaurus, Sagittary[1] |

| Region | Greece, Cyprus |

| Habitat | Land |

A centaur (/ˈsɛntɔːr/; Template:Lang-el, kéntauros, Template:Lang-la), or occasionally hippocentaur, (centauress in feminine form) is a creature from Greek mythology with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse.[2][3] Centaurs are thought of in many Greek myths as being as wild as untamed horses, and were said to have inhabited the region of Magnesia and Mount Pelion in Thessaly, the Foloi oak forest in Elis, and the Malean peninsula in southern Laconia. Centaurs are subsequently featured in Roman mythology, and were familiar figures in the medieval bestiary. They remain a staple of modern fantastic literature.

Mythology

Creation of centaurs

The centaurs were usually said to have been born of Ixion and Nephele.[4] As the story goes, Nephele was a cloud made into the likeness of Hera in a plot to trick Ixion into revealing his lust for Hera to Zeus. Ixion seduced Nephele and from that relationship centaurs were created.[5] Another version, however, makes them children of Centaurus, a man who mated with the Magnesian mares. Centaurus was either himself the son of Ixion and Nephele (inserting an additional generation) or of Apollo and the nymph Stilbe. In the latter version of the story, Centaurus's twin brother was Lapithes, ancestor of the Lapiths.

Another tribe of centaurs was said to have lived on Cyprus. According to Nonnus, they were fathered by Zeus, who, in frustration after Aphrodite had eluded him, spilled his seed on the ground of that land. Unlike those of mainland Greece, the Cyprian centaurs were horned.[6][7]

There were also the Lamian Pheres, twelve rustic daimones (spirits) of the Lamos river. They were set by Zeus to guard the infant Dionysos, protecting him from the machinations of Hera, but the enraged goddess transformed them into ox-horned Centaurs. The Lamian Pheres later accompanied Dionysos in his campaign against the Indians.[8]

The centaur's half-human, half-horse composition has led many writers to treat them as liminal beings, caught between the two natures they embody in contrasting myths; they are both the embodiment of untamed nature, as in their battle with the Lapiths (their kin), and conversely, teachers like Chiron.[citation needed]

Centauromachy

The Centaurs are best known for their fight with the Lapiths who, according to one origin myth, would have been cousins to the centaurs. The battle, called the Centauromachy, was caused by the centaurs' attempt to carry off Hippodamia and the rest of the Lapith women on the day of Hippodamia's marriage to Pirithous, who was the king of the Lapithae and a son of Ixion. Theseus, a hero and founder of cities, who happened to be present, threw the balance in favour of the Lapiths by assisting Pirithous in the battle. The Centaurs were driven off or destroyed.[9][10][11] Another Lapith hero, Caeneus, who was invulnerable to weapons, was beaten into the earth by Centaurs wielding rocks and the branches of trees. In her article "The Centaur: Its History and Meaning in Human Culture," Elizabeth Lawrence claims that the contests between the centaurs and the Lapiths typify the struggle between civilization and barbarism.[12]

The Centauromachy is most famously portrayed in the Parthenon metopes by Phidias and in a Renaissance-era sculpture by Michelangelo.

Etymology

The Greek word kentauros is generally regarded as being of obscure origin.[13] The etymology from ken + tauros, "piercing bull," was a euhemerist suggestion in Palaephatus' rationalizing text on Greek mythology, On Incredible Tales (Περὶ ἀπίστων), which included mounted archers from a village called Nephele eliminating a herd of bulls that were the scourge of Ixion's kingdom.[14] Another possible related etymology can be "bull-slayer".[15]

Origin of the myth

The most common theory holds that the idea of centaurs came from the first reaction of a non-riding culture, as in the Minoan Aegean world, to nomads who were mounted on horses. The theory suggests that such riders would appear as half-man, half-animal. Bernal Díaz del Castillo reported that the Aztecs also had this misapprehension about Spanish cavalrymen.[16] The Lapith tribe of Thessaly, who were the kinsmen of the Centaurs in myth, were described as the inventors of horse-back riding by Greek writers. The Thessalian tribes also claimed their horse breeds were descended from the centaurs.

Robert Graves (relying on the work of Georges Dumézil,[17] who argued for tracing the centaurs back to the Indian Gandharva), speculated that the centaurs were a dimly remembered, pre-Hellenic fraternal earth cult who had the horse as a totem.[18] A similar theory was incorporated into Mary Renault's The Bull from the Sea.

Variations

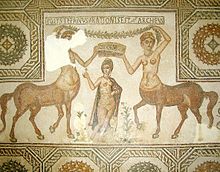

Female centaurs

Though female centaurs, called centaurides or centauresses, are not mentioned in early Greek literature and art, they do appear occasionally in later antiquity. A Macedonian mosaic of the 4th century BC is one of the earliest examples of the centauress in art.[19] Ovid also mentions a centauress named Hylonome[i] who committed suicide when her husband Cyllarus was killed in the war with the Lapiths.[20]

India

The Kalibangan cylinder seal, dated to be around 2600-1900 BC,[21] found at the site of Indus-Valley civilization shows a battle between men in the presence of centaur-like creatures.[22][21] Other sources claim the creatures represented are actually half human and half tigers, later evolving into the Hindu Goddess of War.[23][24] These seals are also evidence of Indus-Mesopotamia relations in the 3rd millennium BC.

In a popular legend associated with Pazhaya Sreekanteswaram Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, the curse of a saintly Brahmin transformed a handsome Yadava prince into a creature having a horse's body and the prince's head, arms, and torso in place of the head and neck of the horse.

Kinnaras, another half-man, half-horse mythical creature from Indian mythology, appeared in various ancient texts, arts, and sculptures from all around India. It is shown as a horse with the torso of a man where the horse's head would be, and is similar to a Greek centaur.[25][26]

Russia

A centaur-like half-human, half-equine creature called Polkan appeared in Russian folk art and lubok prints of the 17th–19th centuries. Polkan is originally based on Pulicane, a half-dog from Andrea da Barberino's poem I Reali di Francia, which was once popular in the Slavonic world in prosaic translations.

Artistic representations

Classical art

The extensive Mycenaean pottery found at Ugarit included two fragmentary Mycenaean terracotta figures which have been tentatively identified as centaurs. This finding suggests a Bronze Age origin for these creatures of myth.[27] A painted terracotta centaur was found in the "Hero's tomb" at Lefkandi, and by the Geometric period, centaurs figure among the first representational figures painted on Greek pottery. An often-published Geometric period bronze of a warrior face-to-face with a centaur is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[28]

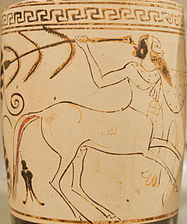

In Greek art of the Archaic period, centaurs are depicted in three different forms. Some centaurs are depicted with a human torso attached to the body of a horse at the withers, where the horse's neck would be; this form, designated "Class A" by Professor Paul Baur, later became standard. "Class B" centaurs are depicted with a human body and legs joined at the waist to the hindquarters of a horse; in some cases centaurs of both Class A and Class B appear together. A third type, designated "Class C", depicts centaurs with human forelegs terminating in hooves. Baur describes this as an apparent development of Aeolic art, which never became particularly widespread.[29] At a later period, paintings on some amphorae depict winged centaurs.[30]

Centaurs were also frequently depicted in Roman art. One example is the pair of centaurs drawing the chariot of Constantine the Great and his family in the Great Cameo of Constantine (circa AD 314–16), which embodies wholly pagan imagery, and contrasts sharply with the popular image of Constantine as the patron of early Christianity.[31][32]

Medieval art

Centaurs preserved a Dionysian connection in the 12th-century Romanesque carved capitals of Mozac Abbey in the Auvergne. Other similar capitals depict harvesters, boys riding goats (a further Dionysiac theme), and griffins guarding the chalice that held the wine. Centaurs are also shown on a number of Pictish carved stones from north-east Scotland erected in the 8th–9th centuries AD (e.g., at Meigle, Perthshire). Though outside the limits of the Roman Empire, these depictions appear to be derived from Classical prototypes.

Modern art

The John C. Hodges library at The University of Tennessee hosts a permanent exhibit of a "Centaur from Volos" in its library. The exhibit, made by sculptor Bill Willers by combining a study human skeleton with the skeleton of a Shetland pony, is entitled "Do you believe in Centaurs?". According to the exhibitors, it was meant to mislead students in order to make them more critically aware.[33]

Another exhibit by Willers is now on long-term display at the International Wildlife Museum in Tucson, Arizona. The full-mount skeleton of a Centaur, built by Skulls Unlimited International, Inc., is on display along with several other fabled creatures, including the Cyclopes, Unicorn, and Griffin.

In Heraldry

Centaurs are common in European heraldry, although more frequent in continental than in British arms. A centaur holding a bow is referred to as a sagittarius.[34]

Literature

Classical literature

Jerome's version of the Life of St Anthony the Great, written by Athanasius of Alexandria about the hermit monk of Egypt, was widely disseminated in the Middle Ages; it relates Anthony's encounter with a centaur who challenged the saint, but was forced to admit that the old gods had been overthrown. The episode was often depicted in The Meeting of St Anthony Abbot and St Paul the Hermit by the painter Stefano di Giovanni, who was known as "Sassetta".[35] Of the two episodic depictions of the hermit Anthony's travel to greet the hermit Paul, one is his encounter with the demonic figure of a centaur along the pathway in a wood.

Lucretius, in his first-century BC philosophical poem On the Nature of Things, denied the existence of centaurs based on their differing rate of growth. He states that at the age of three years, horses are in the prime of their life while humans at the same age are still little more than babies, making hybrid animals impossible.[36]

Modern day literature

C.S. Lewis' The Chronicles of Narnia series depicts centaurs as the wisest and noblest of creatures. Narnian Centaurs are gifted at stargazing, prophecy, healing, and warfare; a fierce and valiant race always faithful to the High King Aslan the Lion.

In J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series, centaurs live in the Forbidden Forest close to Hogwarts, preferring to avoid contact with humans. They live in societies called herds and are skilled at archery, healing, and astrology, but like in the original myths, they are known to have some wild and barbarous tendencies.

With the exception of Chiron, the centaurs in Rick Riordan's Percy Jackson & the Olympians are seen as wild party-goers who use a lot of American slang. Chiron retains his mythological role as a trainer of heroes and is skilled in archery. In Riordan's subsequent series, Heroes of Olympus, another group of centaurs are depicted with more animalistic features (such as horns) and appear as villains, serving the Gigantes.

Philip Jose Farmer's World of Tiers series (1965) includes centaurs, called Half-Horses or Hoi Kentauroi. His creations address several of the metabolic problems of such creatures—how could the human mouth and nose intake sufficient air to sustain both itself and the horse body and, similarly, how could the human ingest sufficient food to sustain both parts.

Brandon Mull's Fablehaven series features centaurs that live in an area called Grunhold. The centaurs are portrayed as a proud, elitist group of beings that consider themselves superior to all other creatures. The fourth book also has a variation on the species called an Alcetaur, which is part man, part moose.

The myth of the centaur appears in John Updike's novel The Centaur. The author depicts a rural Pennsylvanian town as seen through the optics of the myth of the centaur. An unknown and marginalized local school teacher, just like the mythological Chiron did for Prometheus, gave up his life for the future of his son who had chosen to be an independent artist in New York.

Gallery

-

Botticelli, Pallas and Centaur (1482–83)

-

Antonio Canova, Theseus Defeats the Centaur (1805-1819)

-

Prince Bova fights Polkan, Russian lubok (1860)

-

A bronze statue of a centaur, after the Furietti Centaurs

See also

Other hybrid creatures appear in Greek mythology, always with some liminal connection that links Hellenic culture with archaic or non-Hellenic cultures:

- Furietti Centaurs

- Hippocamp

- Hybrid (mythology)

- Ipotane

- Legendary creature

- Lists of legendary creatures

- Minotaur

- Onocentaur

- Ichthyocentaur

- Sagittarius

- Satyr

Also,

- Hindu Kamadhenu

- Indian Kinnara which are half-horse and half-man creature.

- Islamic Buraq, a heavenly steed often portrayed as an equine being with a human face.

- Philippine Tikbalang

- Roman Faun, and the Hippopodes of Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, and later authors.

- Scottish Each uisge and Nuckelavee

- Welsh Ceffyl Dŵr

Additionally, Bucentaur, the name of several historically important Venetian vessels, was linked to a posited ox-centaur or βουκένταυρος (boukentauros) by fanciful and likely spurious folk-etymology.

Footnotes

- ^ The name Hylonome is Greek, so Ovid may have drawn her story from an earlier Greek writer.

References

- ^ For Collins English Dictionary: "sagittary." Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014. 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014. HarperCollins Publishers 1 Sep. 2019 https://www.thefreedictionary.com/sagittary

- ^ "Definition of centaur". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Webster's Third New International Dictionary, G. & C. Merriam Company (1961), s.v. hippocentaur.

- ^ Nash, Harvey (June 1984). "The Centaur's Origin: A Psychological Perspective". The Classical World. 77 (5): 273–291. doi:10.2307/4349592. JSTOR 4349592.

- ^ Alexander, Jonathann. "Tzetzes, Chiliades 9". Theoi.com. Theoi Project. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca, v. 611 ff, xiv. 193 ff, xxxii. 65 ff.

- ^ "CYPRIAN CENTAURS (Kentauroi Kyprioi) - Half-Horse Men of Greek Mythology". www.theoi.com.

- ^ "LAMIAN PHERES - Centaurs of Dionysus in Greek Mythology". www.theoi.com.

- ^ Plutarch, Theseus, 30.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses xii. 210.

- ^ Diodorus Siculusiv. pp. 69-70.

- ^ Lawrence, Elizabeth Atwood (1994). "The Centaur: Its History and Meaning in Human Culture". Journal of Popular Culture. 27 (4): 58.

- ^ Scobie, Alex (1978). "The Origins of 'Centaurs'". Folklore. 89 (2): 142–147. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1978.9716101.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Scobie quotes Martin P. Nilsson (1955). Geschichte der griechischen Religion.Die Etymologie und die Deutung der Ursprungs sind unsicher und mögen auf sich beruhen

- ^ Scobie (1978), p. 142.

- ^ Alexander Hislop, in his polemic The Two Babylons: Papal Worship Revealed to be the Worship of Nimrod and His Wife. (1853, revised 1858) theorized that the word is derived from the Semitic Kohen and "tor" (to go round) via phonetic shift the less prominent consonants being lost over time, with it developing into Khen Tor or Ken-Tor, and being transliterated phonetically into Ionian as Kentaur, but this is not accepted by any modern philologist.

- ^ Stuart Chase. "Chapter IV: The Six Hundred". Mexico: A Study of Two Americas. Retrieved 24 April 2006 – via University of Virginia Hypertexts.

{{cite book}}: External link in|via= - ^ Dumézil, Le Problème des Centaures (Paris 1929) and Mitra-Varuna: An essay on two Indo-European representations of sovereignty (1948. tr. 1988).

- ^ Graves, The Greek Myths, 1960 § 81.4; § 102 "Centaurs"; § 126.3;.

- ^ Pella Archaeological Museum

- ^ Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses, xii. 210 ff.

- ^ a b Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 239–246.

- ^ Ameri, Marta; Costello, Sarah Kielt; Jamison, Gregg; Scott, Sarah Jarmer (2018). Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108168694.

- ^ Parpola, Asko. Deciphering the Indus Script. Cambridge Univ. Press.

- ^ "Indus Cylinder Seals". Harappa.com. May 4, 2016. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- ^ Devdutt Pattanaik, “Indian mythology : tales, symbols, and rituals from the heart of the Subcontinent” (Rochester, USA 2003) P.74: ISBN 0-89281-870-0.

- ^ K. Krishna Murthy, Mythical Animals in Indian Art (New Delhi, India 1985).

- ^ Ione Mylonas Shear, "Mycenaean Centaurs at Ugarit" The Journal of Hellenic Studies (2002:147–153); but see the interpretation relating them to "abbreviated group" figures at the Bronze-Age sanctuary of Aphaia and elsewhere, presented by Korinna Pilafidis-Williams, "No Mycenaean Centaurs Yet", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 124 (2004), p. 165, which concludes "we had perhaps do best not to raise hopes of a continuity of images across the divide between the Bronze Age and the historical period."

- ^ "Bronze man and centaur". The MET. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- ^ Paul V. C. Baur, Centaurs in Ancient Art: The Archaic Period, Karl Curtius, Berlin (1912), pp. 5–7.

- ^ Maria Cristina Biella and Enrico Giovanelli, Il bestiario fantastico di età orientalizzante nella penisola italiana (Belfast, ME: Tangram, 2012), 172-78. ISBN 9788864580692; and J. Michael Padgett and William A. P. Childs, The Centaur's Smile: The Human Animal in Early Greek Art (Princeton University Press, 2003). ISBN 9780300101638

- ^ The Great Cameo of Constantine, formerly in the collection of Peter Paul Rubens and now in the Geld en Bankmuseum, Utrecht, is illustrated, for instance, in Paul Stephenson, Constantine, Roman Emperor, Christian Victor, 2010:fig. 53.

- ^ Iain Ferris, The Arch of Constantine: Inspired by the Divine, Amberley Publishing (2009).

- ^ Anderson, Maggie (August 26, 2004). "Library hails centaur's 10th anniversary". 97 (7 or 8). Archived from the original on September 20, 2007. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Arthur Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, T.C. and E.C. Jack, London, 1909, p 228, https://archive.org/details/completeguidetoh00foxduoft.

- ^ National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC: illustration.

- ^ Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, book V, translated by William Ellery Leonard, 1916 (The Perseus Project.) Retrieved 27 July 2008.

Further reading

- M. Grant and J. Hazel. Who's Who in Greek Mythology. David McKay & Co Inc, 1979.

- Rose, Carol (2001). Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth. New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 72. ISBN 0-393-32211-4.

- Homer's Odyssey, Book 21, 295ff

- Harry Potter, books 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

- The Chronicles of Narnia, book 2.

- Percy Jackson & the Olympians, book 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

- Frédérick S. Parker. Finding the Kingdom of the Centaurs.

External links

- Theoi Project on Centaurs in literature

- Centaurides on female centaurs

- MythWeb article on centaurs

- Harry Potter Lexicon article on centaurs in the Harry Potter universe

- Erich Kissing's centaurs contemporary art