K. Kamaraj: Difference between revisions

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

=== Political interests === |

=== Political interests === |

||

Kamaraj showed an interest in public happenings and politics since the age of 13. While working in his uncle's shop, he began to attend [[Panchayati raj in India|panchayat]]s and other political meetings addressed by activists such as [[P. Varadarajulu Naidu]] and [[George Joseph (activist)|George Joseph]]. He keenly followed ''[[Swadesamitran]]'', a [[Tamil language|Tamil]] daily and often discussed the happenings with people of his age at the shop.{{sfn|Kandaswamy|2001|p=23}} |

Kamaraj showed an interest in public happenings and politics since the age of 13. While working in his uncle's shop, he began to attend [[Panchayati raj in India|panchayat]]s and other political meetings addressed by activists such as [[P. Varadarajulu Naidu]] and [[George Joseph (activist)|George Joseph]]. He keenly followed ''[[Swadesamitran]]'', a [[Tamil language|Tamil]] daily and often discussed the happenings with people of his age at the shop.{{sfn|Kandaswamy|2001|p=23}} |

||

Kamaraj was attracted by [[Annie Besant]]'s [[Home Rule Movement (India)|Home Rule Movement]] and inspired by the writings of [[Bankim Chandra Chatterjee]] and [[Subramania Bharati]]. Due to his inclination towards politics and not spending time on the business, he was sent to [[Thiruvananthapuram]] to work at a [[timber]] shop owned by another of his uncles. While in Kerala, he continued to participate in public activities and took part in the [[Vaikom Satyagraha]], which was conducted for getting access to the prohibited public areas of the [[Vaikom Sree Mahadeva Temple|Vaikom Temple]] to people of all castes.{{sfn|Sanjeev|Nair|1989|p=144}} Kamaraj was called back to his native and despite attempts by his mother to find him a bride, Kamraj refused to get married.{{sfn|Kandaswamy|2001|p=26}} |

|||

== Early political career (1919-29) == |

== Early political career (1919-29) == |

||

Revision as of 11:16, 29 April 2024

K. Kamaraj | |

|---|---|

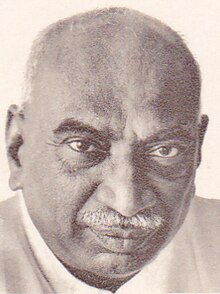

Portrait of Kamaraj from a 1976 commemorative stamp | |

| 3rd Chief Minister of Madras State | |

| In office 13 April 1954 – 2 October 1963 | |

| Governor | |

| Preceded by | C. Rajagopalachari |

| Succeeded by | M. Bhaktavatsalam |

| Constituency |

|

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |

| In office 9 January 1969 – 2 October 1975 | |

| Prime Minister | Indira Gandhi |

| Preceded by | A. Nesamony |

| Succeeded by | Kumari Ananthan |

| Constituency | Nagercoil |

| In office 13 May 1952 – 12 April 1954 | |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | U. Muthuramalingam Thevar |

| Constituency | Srivilliputhur |

| President of the Indian National Congress (Organisation) | |

| In office 12 November 1969 – 2 October 1975 | |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | Morarji Desai |

| President of the Indian National Congress | |

| In office 1964–1967 | |

| Preceded by | Neelam Sanjiva Reddy |

| Succeeded by | S. Nijalingappa |

| President of the Tamil Nadu Pradesh Congress Committee | |

| In office 1946–1952 | |

| Succeeded by | P. Subbarayan |

| Member of the Madras State Legislative Assembly | |

| In office 6 August 1954 – 28 February 1967 | |

| Constituency |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kumaraswami Kamaraj 15 July 1903 Virudhupatti, Madras Presidency, British India (present-day Virudhunagar district, Tamil Nadu, India) |

| Died | 2 October 1975 (aged 72) Madras, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Resting place | Perunthalaivar Kamarajar Ninaivagam |

| Political party | Indian National Congress (until 1969) Indian National Congress (O) (1969–75) |

| Residences |

|

| Profession | |

| Awards | Bharat Ratna (1976) Copper Bond Award (1972) |

| Signature | |

| Nicknames |

|

Kumaraswami Kamaraj (15 July 1903 – 2 October 1975), popularly known as Kamarajar was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the Chief Minister of Madras from 13 April 1954 to 2 October 1963. He also served as the president of the Indian National Congress between 1964–1967 and was responsible for the elevation of Lal Bahadur Shastri and later Indira Gandhi to the position of Prime Minister of India, because of which he was widely acknowledged as the "Kingmaker" in Indian politics during the 1960s. Later, he was the founder and president of the Indian National Congress (O).

Born as Kamatchi, Kamaraj had dropped out of school early and had little formal education. He became active in the Indian Independence movement in the 1920s and was imprisoned by the British Raj multiple times due to his activities. In 1937, Kamaraj was elected to the Madras Legislative Assembly after winning in the 1937 Madras Presidency Legislative Assembly election. He was active during the Quit India Movement in 1942, because of which he was incarcerated for three years till 1945.

After the Indian Independence, Kamaraj served as a Member of Parliament in the Lok Sabha from 1952 to 1954 before becoming the Chief Minister of Madras State in April 1954. During his almost decade long tenure as the chief minister, he played a major role in developing the infrastructure of the state and improving the quality of life of the needy and the disadvantaged. He was responsible for introducing free education to children and expanded the free Midday Meal Scheme, which resulted in significant improvement in school enrollment and growth of literacy rates in the state over the decade. He is widely known as Kalvi Thanthai (Father of education) because of his role in improving the educational infrastructure.

Kamaraj was known for his simplicity and integrity. He remained a bachelor throughout his life and did not own any property when he died in 1963. Former Vice-president of the United States Hubert Humphrey, referred to Kamaraj as one of the greatest political leaders in all the countries. He was awarded with India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, posthumously in 1976.

Family and childhood

Early life

Kamaraj was born on 15 July 1903 in Virudhupatti, Madras Presidency, to Kumaraswami Nadar and Sivakami Ammal.[1] His father Kumaraswami Nadar was a coconut merchant and his parents named him Kamatchi, after their family deity.[2] His parents called him as Raja and the portmanteau of both the names became Kamaraj later.[3] Kamaraj had a younger sister named Nagammal.[4] At the age of five, Kamaraj was enrolled in the local elementary school being admitted in the high school later. Kamaraj's grandfather and father died in quick succession when he was only six years old with his mother forced to support the family.[2] Later, Kamaraj dropped out of school at the age of 12 and joined a cloth shop run by his maternal uncle as a salesman.[5][6] He learnt Silambam, an ancient martial art and also spent time singing bhajans of lord Muruga along with the locals.[7]

Political interests

Kamaraj showed an interest in public happenings and politics since the age of 13. While working in his uncle's shop, he began to attend panchayats and other political meetings addressed by activists such as P. Varadarajulu Naidu and George Joseph. He keenly followed Swadesamitran, a Tamil daily and often discussed the happenings with people of his age at the shop.[7]

Kamaraj was attracted by Annie Besant's Home Rule Movement and inspired by the writings of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee and Subramania Bharati. Due to his inclination towards politics and not spending time on the business, he was sent to Thiruvananthapuram to work at a timber shop owned by another of his uncles. While in Kerala, he continued to participate in public activities and took part in the Vaikom Satyagraha, which was conducted for getting access to the prohibited public areas of the Vaikom Temple to people of all castes.[8] Kamaraj was called back to his native and despite attempts by his mother to find him a bride, Kamraj refused to get married.[9]

Early political career (1919-29)

After the Rowlatt Act of 1919 which indefinitely extended preventive detention and imprisonment of Indians without trial, was passed by the British Raj and the subsequent Jallianwala Bagh massacre, where hundreds of peaceful protesters against the act were shot down, Kamaraj decided to join Indian National Congress at the age of 16.[10][8]

On 21 September 1921, he met Mahatma Gandhi for the first time during a meeting in Madurai and was influenced by his views on prohibition of alcohol, usage of khadi, non violence and eradication of untouchability. In 1922, Kamaraj traveled to Chennai to partake in protest against the visit of Prince of Wales as a part of the Non-cooperation movement. He was later elected to be a part of the town committee of the Congress in Virudhunagar. As a part of the role, he collected donations to finance the printing of speeches of Gandhi and distributed them to the people to induce them to join the Indian Independence movement.[11] In the next few years, Kamaraj participated in the Flag Satyagraha in Nagpur and the Sword Satyagraha in Madras. He organized regular meetings of the Congress in the Madurai district and started orating.[12]

Independence activism (1930-47)

In 1930, Kamaraj participated in the Vedaranyam march organized by C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) in support of Gandhi's Salt March. He was arrested for the first time and was imprisoned in Alipore Jail for almost two years. He was released before he served the two-year sentence as the Gandhi–Irwin Pact in 1931.[13] In 1931, he was appointed as a member of All India Congress Committee. In the next decade, the Congress in Madras province was divided into two led with one being led by Rajaji and the other led by S. Satyamurti. Kamaraj supported Satyamurti, as he aligned closely with the ideals propagated by him. In the 1931 elections to the regional unit of the Congress, he helped Satyamurti to win the post of vice-president.[14] In 1932, Kamaraj was arrested again on charges of sedition and inciting violence. He was sentenced to one year of rigorous imprisonment at Tiruchirappalli. He was later transferred to Vellore Central Prison, where he developed an association with revolutionaries like Jaidev Kapoor and Kamal Nath Tewari. In 1933-34, Kamaraj was charged with a conspiracy to murder John Anderson, then Governor of Bengal, which was part of a larger Madras Conspiracy Case. He was accused of supplying arms but was acquitted due to lack of evidence in 1934.[15]

On 21 September 1933, a post office and the police station in Virudhunagar were bombed. On 9 November, Kamaraj was implicated in the bombing despite the local police inspector giving statement to the contrary. Indian police officials along with the British officers engaged in coercive tactics and harassment to try and force a confession in the case. Varadarajulu Naidu and George Joseph argued on Kamaraj's behalf in court and the charges were proved to be baseless.[16] Despite his acquittal, Kamaraj had sold most of his ancestral properties apart from the house to finance the case.[17] In the 1934 elections, he organized the campaign for Congress and was appointed the general secretary of the provincial congress committee in 1936. In 1937, in the Madras Presidency Legislative Assembly election, Kamaraj was elected as a member of legislative assembly (MLA) with the Congress gaining a simple majority, winning 156 of the 219 seats.[18][19] In 1940, Kamaraj was elected as the president of the provincial congress committee.[20]

In 1940, Kamaraj conducted a campaign asking people not to contribute to war funds when Arthur Hope, the Governor of Madras was collecting contributions to fund the Allies in the Second World War. In December 1940, he was arrested under the Defence of India rules for speeches that opposed contributions to the war fund, and sent to Vellore prison.[21] While in jail, he was elected as a municipal councilor of Virudhunagar and was handed the chairmanship of the council when he was released from the the jail in November 1941. He resigned from the post immediately as he thought he had greater responsibility for the nation and further stated that "One should not accept any post to which one could not do full justice".[22]

In 1942, Kamaraj attended the All-India Congress Committee in Bombay and returned to spread propaganda material for the Quit India Movement. The police issued orders to all the leaders who attended this Bombay session. Kamaraj did not want to be arrested before he took the message to all district and local leaders. After finishing his work, he sent a message to the local police that he was ready to be arrested. He was arrested in August 1942. He was under detention for three years and was released in June 1945. This was his last prison term.[23] Kamaraj was imprisoned six times by the British for his pro-Independence activities, that added up to more than 3,000 days in jail.[24]

During the anti-cow slaughter agitation in 1966, Kamaraj's house near the parliament was burnt down by Hindutva groups. The agitation was incited by Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the political arm of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).[25][26][27] They also surrounded his house with an intent to attack him.[26] Kamaraj had a narrow escape.[28]

Chief Minister of Madras

On 13 April 1954, Kamaraj became the Chief Minister of Madras Province. To everyone's surprise, Kamaraj nominated C. Subramaniam, who had contested his leadership, to the newly formed cabinet. Shri K. KamaraJ has resigned his MP seat in the House with effect from the 9th August, 1954.[29]

As Chief Minister, Kamaraj removed the family vocation based Modified Scheme of Elementary education 1953 introduced by Rajaji. He reopened 6000 schools closed in the previous government by C. Rajagopalachari citing financial reasons and reopened 12,000 more schools. The State made immense strides in education and trade. New schools were opened, so that poor rural students had to walk no more than three kilometres to their nearest school. Better facilities were added to existing ones. No village remained without a primary school and no panchayat without a high school. Kamaraj strove to eradicate illiteracy by introducing free and compulsory education up to the eleventh standard. He introduced the Midday Meal Scheme to provide at least one meal per day to the lakhs of poor school children.[30] He introduced free school uniforms to weed out caste, creed and class distinctions among young minds.[31]

During the colonial era, the local education rate was at 7%; after Kamaraj's reforms, it reached 37%. Apart from increasing the number of schools, steps were taken to improve standards of education. To improve standards, the number of working days was increased from 180 to 200; unnecessary holidays were reduced; and syllabi were prepared to give opportunity to various abilities. Kamaraj and Bishnuram Medhi (Governor) took efforts to establish IIT Madras in 1959.[18]

Major irrigation schemes were planned in Kamaraj's period. Dams and irrigation canals were built across higher Bhavani, Mani Muthar, Aarani, Vaigai, Amaravathi, Sathanur, Krishnagiri, Pullambadi, Parambikulam and Neyyaru among others. The Lower Bhavani Dam in Erode district brought 207,000 acres (840 km2) of land under cultivation. 45,000 acres (180 km2) of land benefited from canals constructed from the Mettur Dam. The Vaigai and Sathanur systems facilitated cultivation across thousands of acres of lands in Madurai and North Arcot districts respectively. Rs 30 crores were planned to be spent for Parambikulam River scheme, and 150 lakhs of acres of lands were brought under cultivation; one third of this (i.e. 56 lakhs of acres of land) received a permanent irrigation facility. In 1957–61 1,628 tanks were de-silted under the Small Irrigation Scheme, and 2,000 wells were dug with outlets. Long-term loans with 25% subsidy were given to farmers. In addition farmers who had dry lands were given oil engines and electric pump sets on an instalment basis.

Industries with huge investments in crores of Rupees were started in his period: Neyveli Lignite Corporation, BHEL at Trichy, Manali Refinery, Hindustan raw photo film factory at Ooty, surgical instruments factory at Chennai, and a railway coach factory at Chennai were established. Industries such as paper, sugar, chemicals and cement took off during the period.

On 6 September 1959, Kamaraj overtook the Raja of Panagal's record of being the longest-serving Chief Minister (up till that point, no Chief Minister had served 5 years straight except the Raja). On his retirement, he became the longest-serving Chief Minister of the state serving a record 9 years. He remains the longest-serving Chief Minister of Madras State (1950-1969) and he also has the longest uninterrupted tenure of any Chief Minister till date [while Karunanidhi was the longest-serving CM in terms of cumulative durations, it was spread out across 5 different tenures - none of which touched or crossed the 3,000-day mark]].

Kamaraj Plan

Kamaraj remained Chief Minister for three consecutive terms, winning elections in 1957 and 1962. By the mid 1960s, Kamaraj noticed that the Congress party was slowly losing its vigour, and on Gandhi Jayanti day 2 October 1963, he resigned from the post of the Chief Minister. He proposed that all senior Congress leaders should resign from their posts and devote all their energy to the re-vitalization of the Congress.

In 1963 he suggested to Nehru that senior Congress leaders should leave ministerial posts to take up organisational work. This suggestion came to be known as the Kamaraj Plan, which was designed primarily to dispel from the minds of Congressmen the lure of power, creating in its place a dedicated attachment to the objectives and policies of the organisation. Six Union Ministers and six Chief Ministers including Lal Bahadur Shastri, Jagjivan Ram, Morarji Desai, Biju Patnaik and S.K. Patil followed suit and resigned from their posts.[32] Impressed by Kamaraj's achievements and acumen, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru felt that his services were needed more at the national level.[citation needed] In a swift move he brought Kamaraj to Delhi as the President of the Indian National Congress. Nehru realised that in addition to wide learning and vision, Kamaraj possessed enormous common sense and pragmatism. Kamaraj was elected the President of Indian National Congress on 9 October 1963.[33][34]

National politics

After Nehru's death in 1964, Kamaraj successfully navigated the party through turbulent times. As the president of INC, he refused to become the next prime minister himself and was instrumental in bringing to power two Prime Ministers, Lal Bahadur Shastri in 1964 and Nehru's daughter Indira Gandhi 1966.[35] For this role, he was widely acclaimed as the "kingmaker" during the 1960s.[36]

When the Congress split in 1969, Kamaraj became the leader of the Indian National Congress (Organisation) (INC(O)) in Tamil Nadu. The party fared poorly in the 1971 elections amid allegations of fraud by the opposition parties. He remained the leader of INC(O) until his death in 1975.[37]

Electoral history

| Year | Post | Constituency | Party | Opponent | Election | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | MLA | Sattur | INC | Unopposed | 1937 elections | Won |

| 1946 | MLA | Sattur-Aruppukottai | INC | Unopposed | 1946 elections | Won |

| 1952 | MP | Srivilliputhur | INC | G. D. Naidu | Indian General Elections, 1951 | Won |

| 1954 | MLA | Gudiyatham | INC | V. K. Kothandaraman | By Election | Won |

| 1957 | MLA | Sattur | INC | Jayarama Reddiar | 1957 Madras legislative assembly election | Won |

| 1962 | MLA | Sattur | INC | P. Ramamoorthy | 1962 Madras legislative assembly election | Won |

| 1967 | MLA | Virudhunagar | INC | P. Seenivasan | 1967 Tamil Nadu state assembly election | Lost[38] |

| 1969 | MP | Nagercoil | INC | M. Mathias | By Election | Won |

| 1971 | MP | Nagercoil | INC(O) | M. C. Balan | Indian General Elections, 1971 | Won |

The death of A. Nesamony in 1968 led to the by-election in Nagercoil Lok Sabha constituency. Realising the popularity of Kamaraj in this constituency and the potential danger posed by Kamaraj's election after the Indian National Congress party's debacle in 1967 election, C. Rajagopalachari wrote in Swarajya, the magazine of the Swatantra Party, about the need to defeat him and appealed to C. N. Annadurai to support M. Mathias, the Swatantra Party candidate. Annadurai deputed M. Karunanidhi, the then Minister for Public Works, to Nagercoil to work in support of Mathias. Despite the efforts, Kamaraj won decisively with a 1,28,201-vote margin on 8 January 1969.[39]

Death

On 2 October 1975, Kamaraj complained of chest pain after lunch. He passed away later in his sleep due to a heart attack, aged 72.[40] His body was kept for public viewing at Rajaji Hall. On the next day, it was taken in procession to Gandhi Mandapam and cremated with full state honors.[41] Memorials dedicated to Kamaraj have been established in Chennai, Virudhunagar and Kanniya Kumari.[42][43]

Legacy

Kamaraj spent most of his career in politics and did not spend much time on relationships and family.[44] Kamaraj was known for his simplicity and integrity. He followed Gandhian principles, wore a simple Khadi shirt and dhoti and was often referred to as Black Gandhi by the people.[45] He ate a simple meal and refused special privileges.[46] During his tenure as Chief Minister, when the municipality of Virudhunagar provided a direct water connection to his house, Kamarajar ordered it to be disconnected immediately as he did not want any special privileges and opined that public agencies should serve the public and not private individuals. He often refused police protection and security, determining it as waste of public resources.[47] Kamaraj did not own any property and had a mere ₹130 of money, two pairs of sandals, four pair of shirts and dhotis apart from a few books in his possession when he died.[48]

He was a man of action who believed that any goal could be realized through the correct means and is often referred to as Karma Veerar (man of action) and Perunthalaivar (great or tall leader) in Tamil.[49] Former Vice-president of the United States Hubert Humphrey, referred to Kamaraj as one of the greatest political leaders in all the countries.[50] Though he lacked a formal higher education, he showed good intelligence, intuitiveness and understanding of human nature, which led to him being called by the epithet of Padikkatha Methai (uneducated genius).[2]

In 1976, Kamaraj was posthumously awarded Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian honor.[51] In 2004, Government of India issued special commemorative coins of ₹ 100 and ₹ 5 denomination to mark the centenary celebrations of him.[52]

Many public places, roads and buildings are named after Kamaraj. Madurai University is renamed as Madurai Kamaraj University in his honor.[53]The old domestic terminal of Chennai International Airport is named "Kamaraj Terminal".[54] The port at Ennore in North Chennai has been named as Kamarajar Port Limited.[55] The railway station at Maraimalai Nagar, a municipality south of Chennai, is named as Maraimalai Nagar Kamarajar Railway Station.[56] Major roads bearing his name include the North Parade Road in Bengaluru,[57] Marina Beach Road in Chennai,[58] and Parliament Road in New Delhi.[59] There are many statues dedicated to him across India including at Parliament of India in New Delhi and the Marina Beach facade in Chennai to honor him.[60]

Popular culture

In 2004, a Tamil-language film titled Kamaraj was made based on the life history of Kamaraj.[61]

References

- ^ Kapur, Raghu Pati (1966). Kamaraj, the iron man. Deepak Associates. p. 12.

- ^ a b c Sanjeev & Nair 1989, p. 140.

- ^ Murthi 2005, p. 85.

- ^ "In dire straits, Kamaraj kin get Congress aid for education". The Times of India. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Ramachandra Guha (2017). "18". India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Pan Macmillan. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-5098-8328-8.

- ^ Narasimhan & Narayanan 2007, p. 161.

- ^ a b Kandaswamy 2001, p. 23.

- ^ a b Sanjeev & Nair 1989, p. 144.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Nigel Collett (2006). The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer. A&C Black. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-8528-5575-8.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Sanjeev & Nair 1989, p. 145.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, p. 38.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, p. 36.

- ^ "George Joseph, a true champion of subaltern". The Hindu. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b "K Kamaraj 116th birth anniv: Rare pics of 'Kingmaker'". Deccan Herald. 15 July 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Kandaswamy 2001, p. 39.

- ^ Murthi 2005, p. 88.

- ^ Sanjeev & Nair 1989, p. 146.

- ^ Bhatnagar, R. K. (13 October 2009). "Tributes To Kamaraj". Asian Tribune. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Stepan, Alfred; Linz, Juan J.; Yadav, Yogendra (2011). Crafting State-Nations: India and Other Multinational Democracies. JHU Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780801897238.

- ^ "RSS Chief's Call for National Cow Protection Law Echoes a Familiar Pattern". The Wire. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b Chandra, Bipan (11 February 2008). India Since Independence. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-053-9.

- ^ Marvel, Ishan. "Fifty Years Ago, Hindutva Groups Led the First Attack on the Indian Parliament". The Caravan. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Ramesh, Jairam (9 November 2016). "The very first attack on Parliament". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/55615/1/lsd_01_07_23-08-1954.pdf page 82

- ^ Muthiah, S. (2008). Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India. Palaniappa Brothers. p. 354. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8.

- ^ Sinha, Dipa (20 April 2016). Women, Health and Public Services in India: Why are states different?. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-23525-5.

- ^ Awana, Ram Singh (1988). Pressure Politics in Congress Party: A Study of the Congress Forum for Socialist Action. New Delhi: Northern Book Centre. p. 105. ISBN 9788185119434. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ K Kamaraj. dpcc.co.in Archived 18 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi (2010). Rajaji: A Life. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-9-3858-9033-8.

- ^ "Will Mamata Banerjee's Hindi handicap hurt her ambition to be prime minister?". December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ^ Khan, Farhat Basir (16 September 2019). The Game of Votes: Visual Media Politics and Elections in the Digital Era. SAGE Publishing India. p. 76. ISBN 978-93-5328-693-4.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 164.

- ^ Election Commission of India. "Statistical Report on General Election 1967" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ P. Kandaswamy. The political career of K. Kamraj. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. pp. 122–124.

- ^ "Kumaraswami Kamaraj Dead; Power Broker in Indian Politics". The New York Times. 3 October 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "The last days of King Maker Kamaraj". India Herald. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "CM unveils Kamaraj memorial". The Hindu. 16 July 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Kamarajar memorial". Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Narasimhan & Narayanan 2007, p. 216.

- ^ Sanjeev & Nair 1989, p. 139.

- ^ Narasimhan & Narayanan 2007, p. 213.

- ^ "What the modern, developed Tamil Nadu of today owes to K Kamaraj". The Indian Express. 23 April 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "To regain lost glory, Congress needs a Kamaraj as its leader". The Pioneer. 25 July 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "A true leader". The Hindu. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Chhibber, Maneesh (2 October 2018). "K. Kamaraj: The southern stalwart who gave India two PMs". The Print. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Padma Awards Directory (1954–2007)" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ "Bharat Ratna Shri K. Kamraj-(2 Coin Set-Rs. 100 & 5)". Indian Government Mint. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Man of the people". The Tribune. 4 October 1975. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008.

- ^ "Chennai: Airport terminals to be reconstructed". Deccan Chronicle. 20 November 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Kamarajar port to become 'Cape' compliant". The Hindu. 3 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Maraimalai Nagar Kamarajar Railway Station". Indiarailinfo. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Kamaraj Road in Bengaluru to open as one-way by mid-May". The New Indian Express. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Traffic diversion on Kamarajar Salai for R-Day". The Times of India. 22 January 2024. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Cycle track plan picks up pace, NDMC awaits nod". The Times of India. 12 April 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "How Kamaraj Pioneered The Mid-Day Meal Scheme". Madras Courier. 3 October 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Film on former CM Kamaraj to be re-released with additional content'". The Times of India. 16 January 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

Bibliography

- Kandaswamy, P (2001). Early Life of K. Kamaraj. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-8-1702-2801-1.

- Murthi, R.K. (2005). Encyclopedia of Bharat Ratnas. Pitambar Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-8-1209-1307-3.

- Narasimhan, V.K.; Narayanan, V. N. (2007). Kamaraj, a Study. National Book Trust. ISBN 978-8-1237-4876-4.</ref>

- Sanjeev, Sudha; Nair, Bhavana (1989). Remembering Our Leaders. Vol. 7. Children's Book Trust. ISBN 978-8-1701-1767-4.

External links

- 1903 births

- 1975 deaths

- India MPs 1952–1957

- India MPs 1967–1970

- India MPs 1971–1977

- Chief ministers from Indian National Congress

- Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu

- Indian Hindus

- Indian independence activists

- Indian independence activists from Tamil Nadu

- Indian National Congress (Organisation) politicians

- Indian National Congress politicians from Tamil Nadu

- Indian nationalists

- Indian political party founders

- Indian socialists

- Indian Tamil politicians

- Indian tax resisters

- Gandhians

- Lok Sabha members from Tamil Nadu

- Madras MLAs 1957–1962

- People from Virudhunagar district

- Presidents of the Indian National Congress

- Prisoners and detainees of British India

- Recipients of the Bharat Ratna

- Madras MLAs 1962–1967