Third Anglo-Maratha War

| Third Anglo-Maratha War[1] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Maratha Wars | |||||||

Indian Camp Scene | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

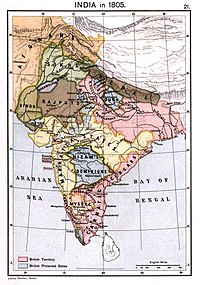

The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) was the final and decisive conflict between the British East India Company (EIC) and the Maratha Empire in India. The war left the Company in control of most of India. It began with an invasion of Maratha territory by British East India Company troops,[2] and although the British were outnumbered, the Maratha army was decimated. The troops were led by Governor General Hastings, supported by a force under General Thomas Hislop. Operations began against the Pindaris, a band of Muslim mercenaries and Marathas from central India.[note 1]

Peshwa Baji Rao II's forces, supported by those of Mudhoji II Bhonsle of Nagpur and Malharrao Holkar III of Indore, rose against the East India Company. Pressure and diplomacy convinced the fourth major Maratha leader, Daulatrao Shinde of Gwalior, to remain neutral even though he lost control of Rajasthan.

British victories were swift, resulting in the breakup of the Maratha Empire and the loss of Maratha independence. The Peshwa was defeated in the battles of Khadki and Koregaon. Several minor battles were fought by the Peshwa's forces to prevent his capture.[4]

The Peshwa was eventually captured and placed on a small estate at Bithur, near Kanpur. Most of his territory was annexed and became part of the Bombay Presidency. The Maharaja of Satara was restored as the ruler of his territory as a princely state. In 1848 this territory was also annexed by the Bombay Presidency under the doctrine of lapse policy of Lord Dalhousie. Bhonsle was defeated in the battle of Sitabuldi and Holkar in the battle of Mahidpur. The northern portion of Bhonsle's dominions in and around Nagpur, together with the Peshwa's territories in Bundelkhand, were annexed by British India as the Saugor and Nerbudda Territories. The defeat of the Bhonsle and Holkar also resulted in the acquisition of the Maratha kingdoms of Nagpur and Indore by the British. Along with Gwalior from Shinde and Jhansi from the Peshwa, all of these territories became princely states acknowledging British control. The British proficiency in Indian war-making was demonstrated through their rapid victories in Khadki, Sitabuldi, Mahidpur, Koregaon, and Satara.[5]

The Marathas and the British

The Maratha Empire was founded in 1674 by Shivaji of the Bhosle dynasty. Common elements among the citizens of Chatrapati Shivaji's Maratha Empire were the Marathi language, the Hindu religion, a strong sense of belonging, and a national feeling.[6] Shivaji led resistance efforts to free the Hindus from the Mughals and Muslim Sultanate of Bijapur and established rule of the Hindus. This kingdom was known as the Hindavi Swarajya ("Hindu self-rule") in the Marathi language. Shivaji's capital was located at Raigad. Chatrapati Shivaji successfully defended his empire from attacks by the Mughal Empire and his Maratha Empire went on to defeat and overtake it as the premier power in India within few decades. A key component of the Maratha administration was the council of eight ministers, called the Ashta Pradhan (council of eight). The senior-most member of the Ashta Pradhan was called the Peshwa or the Mukhya Pradhan (prime minister). [citation needed]

Growing British power

While the Marathas were fighting the Mughals in the early 18th century, the British held small trading posts in Mumbai, Madras and Calcutta. The British fortified the naval post of Mumbai after they saw the Marathas defeat the Portuguese at neighbouring Vasai in May 1739. In an effort to keep the Marathas out of Mumbai, the British sent envoys to negotiate a treaty. The envoys were successful, and a treaty was signed on 12 July 1739 that gave the British East India Company rights to free trade in Maratha territory.[7] In the south, the Nizam of Hyderabad had enlisted the support of the French for his war against the Marathas.[note 2] In reaction to this, the Peshwa requested support from the British, but was refused. Unable to see the rising power of the British, the Peshwa set a precedent by seeking their help to solve internal Maratha conflicts.[8] Despite the lack of support, the Marathas managed to defeat the Nizam over a period of five years.[8]

During the period 1750–1761, British defeated the French East India Company in India, and by 1793 they were firmly established in Bengal in the east and Madras in the south. They were unable to expand to the west as the Marathas were dominant there, but they entered Surat on the west coast via the sea.[9]

The Marathas marched beyond the Indus as their empire grew.[9] The responsibility for managing the sprawling Maratha empire in the north was entrusted to two Maratha leaders, Shinde and Holkar, as the Peshwa was busy in the south.[10] The two leaders did not act in concert, and their policies were influenced by personal interests and financial demands. They alienated other Hindu rulers such as the Rajputs, the Jats, and the Rohillas, and they failed to diplomatically win over other Muslim leaders.[10] A large blow to the Marathas came in their defeat on 14 January 1761 at Panipat against a combined Muslim force that gathered defeating Marathas led by the Afghan Ahmad Shah Abdali. An entire generation of Maratha leaders lay dead on the battlefield as a result of that conflict.[10] However, between 1761 and 1773, the Marathas regained the lost ground in the north.[11]

Anglo-Maratha relations

The Maratha gains in the north were undone because of the contradictory policies of Holkar and Shinde and the internal disputes in the family of the Peshwa, which culminated in the murder of Narayanrao Peshwa in 1773.[12] Raghunathrao was ousted from the seat of Peshwa due to continuing internal Maratha rivalries. He sought help from the British, and they signed the Treaty of Surat with him in March 1775.[13] This treaty gave him military assistance in exchange for control of Salsette Island and Bassein Fort.[14]

The treaty set off discussions amongst the British in India as well as in Europe because of the serious implications of a confrontation with the powerful Marathas. Another cause for concern was that the Bombay Council had exceeded its constitutional authority by signing such a treaty.[15] The treaty was the cause of the start of the First Anglo-Maratha War.[note 3] This war was virtually a stalemate, with no side being able to defeat the other.[16] The war concluded with the treaty of Salabai in May 1782, mediated by Mahadji Shinde. The foresight of Warren Hastings was the main reason for the success of the British in the war. He had destroyed the anti-British coalition and created a division between the Shinde, the Bhonsle, and the Peshwa.[note 4]

The Marathas were still in a very strong position when the new Governor General of British controlled territories Cornwallis arrived in India in 1786.[18] After the treaty of Salabai, the British followed a policy of coexistence in the north. The British and the Marathas enjoyed more than two decades of peace, thanks to the diplomacy of Nana Phadnavis, a minister in the court of the 11-year-old Peshwa Sawai Madhavrao. The situation changed soon after Nana's death in 1800. The power struggle between Holkar and Shinde caused Holkar to attack the Peshwa in Pune in 1801, since the Peshwa sided with Shinde. The Peshwa Baji Rao II fled Pune to safety on a British warship. Baji Rao feared loss of his own powers and signed the treaty of Bassein. This made the Peshwa in effect a subsidiary ally of the British.

In response to the treaty, the Bhonsle and Shinde attacked the British, refusing to accept the betrayal of their sovereignty to the British by the Peshwa. This was the start of the Second Anglo-Maratha War in 1803. Both were defeated by the British, and all Maratha leaders lost large parts of their territory to the British.[16]

The British East India Company

The British had travelled thousands of miles to arrive in India. They studied Indian geography and mastered local languages to deal with the Indians.[note 5] At the time, they were technologically advanced, with superior equipment in several critical areas to that available locally. Chhabra hypothesizes that even if the British technical superiority were discounted, they would have won the war because of the discipline and organization in their ranks.[19] After the First Anglo-Maratha war, Warren Hastings declared in 1783 that the peace established with the Marathas was on such a firm ground that it was not going to be shaken for years to come.[20]

The British believed that a new permanent approach was needed to establish and maintain continuous contact with the Peshwa's court in Pune. The British appointed Charles Malet, a senior merchant from Bombay, to be a permanent Resident at Pune because of his knowledge of the languages and customs of the region.[20]

Prelude

The Maratha Empire had partly declined due to the Second Anglo-Maratha War.[21] Efforts to modernize the armies were half-hearted and undisciplined: newer techniques were not absorbed by the soldiers, while the older methods and experience were outdated and obsolete.[21] The Maratha Empire lacked an efficient spy system, and had weak diplomacy compared to the British. Maratha artillery was outdated, and weapons were imported. Foreign officers were responsible for the handling of the imported guns; the Marathas never used their own men in considerable numbers for the purpose. Although Maratha infantry was praised by the likes of Wellington, they were poorly led by their generals and heavily relied on mercenaries (known as Pindaris). The confederate-like structure that evolved within the empire created a lack of unity needed for the wars.[21]

At the time of the war, the power of the British East India Company was on the rise, whereas the Maratha Empire was on the decline. The British had been victorious in the previous Anglo-Maratha war and the Marathas were at their mercy. The Peshwa of the Maratha Empire at this time was Baji Rao II. Several Maratha leaders who had formerly sided with the Peshwa were now under British control or protection. The British had an arrangement with the Gaekwad dynasty of the Maratha province of Baroda to prevent the Peshwa from collecting revenue in that province. Gaekwad sent an envoy to the Peshwa in Pune to negotiate a dispute regarding revenue collection. The envoy, Gangadhar Shastri, was under British protection. He was murdered, and the Peshwa's minister Trimbak Dengle was suspected of the crime.

The British seized the opportunity to force Baji Rao into a treaty.[22] The treaty (The Treaty of Pune) was signed on 13 June 1817. Key terms imposed on the Peshwa included the admission of Dengle's guilt, renouncing claims on Gaekwad, and surrender of significant swaths of territory to the British. These included his most important strongholds in the Deccan, the seaboard of Konkan, and all places north of the Narmada and south of the Tungabhadra rivers. The Peshwa was also not to communicate with any other powers in India.[23] The British Resident Mountstuart Elphinstone also asked the Peshwa to disband his cavalry.[22]

Maratha planning

The Peshwa disbanded his cavalry, but secretly asked them to stand by, and offered them seven months' advance pay.[24] Baji Rao entrusted Bapu Gokhale with preparations for war.[25] In August 1817, the forts at Sinhagad, Raigad, and Purandar were fortified by the Peshwa.[26] Gokhale secretly recruited troops for the impending war.[26] Many Bhils and Ramoshis were hired. Efforts were made to unify Bhonsle, Shinde, and Holkar; even the mercenary Pindaris were approached.[26] The Peshwa identified unhappy Marathas in the service of the British Resident Elphinstone and secretly recruited them. One such person was Jaswant Rao Ghorpade. Efforts were made to secretly recruit Europeans as well, which failed.[27] Some people, such as Balaji Pant Natu, stood steadfastly with the British.[27] Several of the sepoys rejected the Peshwa's offers,[28] and others reported the matter to their superior officers.[27] On 19 October 1817, Baji Rao II celebrated the Dassera festival in Pune, where troops were assembled in large numbers.[24] During the celebrations, a large flank of the Maratha cavalry pretended they were charging towards the British sepoys but wheeled off at the last minute. This display was intended as a slight towards Elphinstone [29] and as a scare tactic to prompt the defection and recruitment of British sepoys to the Peshwa's side.[29] The Peshwa made plans to kill Elphinstone, despite opposition from Gokhale. Elphinstone was fully aware of these developments thanks to the espionage work of Balaji Pant Natu and Ghorpade.[24]

Burton provides an estimate of the strength of various Maratha powers in or around 1817: He estimated the various Maratha powers totals to 81,000 infantry, 106,000 horse or cavalry and 589 guns. Of these the Peshwa had the highest number of cavalry at 28,000, along with 14,000 infantry and 37 guns. The Peshwa headquarters was in Pune, which was the southernmost location amongst the other Maratha powers. Holkar had the second largest cavalry, amounting to 20,000, and an infantry force of 8,000. His guns totaled to 107 guns. Shinde and Bhonsle had similar numbers of cavalry and infantry, with each having 15,000 and 16,000 cavalry, respectively. Shinde had 16,000 infantry and Bhonsle, 18,000. Shinde had the larger share of guns amounting to 140 whereas Bhonsle had 85. Holkar, Shinde and Bhonsle were headquartered in Indore, Gwalior and Nagpur respectively. The Afghan leader Amir Khan was located in Tonk in Rajputana and his strength was 12,000 cavalry, 10,000 infantry and 200 guns.[30][2][31] The Pindaris were located north of the Narmada valley in Chambal and Malwa region of central India. Three Pindari leaders sided with Shinde, these were Setu, Karim Khan and Dost Mohammad. They were mostly horsemen with strengths of 10,000, 6,000 and 4,000. The rest of the Pindari chiefs, Tulsi, Imam Baksh, Sahib Khan, Kadir Baksh, Nathu and Bapu were allied with Holkar. Tulsi and Imam Baksh each had 2,000 horsemen, Kadir Baksh, 21,500. Sahib Khan, Nathu and Bapu had 1,000, 750 and 150 horsemen.[32]

Commencement

The Peshwa's territory was in an area called the Desha, now part of the modern state of Maharashtra. The region consists of the valleys of the Krishna and Godavari rivers and the plateaus of the Sahyadri Mountains. Shinde's territory around Gwalior and Bundelkhand was a region of rolling hills and fertile valleys that slopes down toward the Indo-Gangetic Plain to the north. The Pindari territory was the valleys and forests of the Chambal, the north western region of the modern state of Madhya Pradesh. It was a mountainous region with a harsh climate. The Pindaris also operated from Malwa, a plateau region in the north west of the state of Madhya Pradesh, north of the Vindhya Range. Holkar was based in the upper Narmada River valley.[33]

The war was mostly a mopping-up operation intended to complete the expansion of the earlier Anglo-Maratha war, which was stopped due to economic concerns of the British.[34] The war began as a campaign against the Pindaris.[35] Seeing that the British were in conflict with the Pindaris, the Peshwa's forces attacked the British at 16:00 on 5 November 1817 with the Maratha left attacking the British right. The Maratha forces comprised 20,000 cavalry, 8,000 infantry, and 20 guns[24] whereas the British had 2,000 cavalry, 1,000 infantry, and eight guns.[36] On the Maratha side, an additional 5,000 horse and 1,000 infantry were guarding the Peshwa at Parvati Hill. The British numbers include Captain Ford's unit, which was en route from Dapodi to Khadki.[36] The British had also asked General Smith to come to Khadki for the battle but they did not anticipate he would arrive in time.[36]

Three hills in the region were the Parvati Hill, the Chaturshringi Hill, and the Khadki hill. The Peshwa watched the battle from the Parvati Hill whereas the British East India Company troops were based on the Khadki hill.[24] The two hills are separated by a distance of four kilometres. The river Mula is shallow and narrow and could be crossed at several locations.[24] A few canals (nallas in Marathi) joined the river and though these were not obstacles, some of them were obscured due to the vegetation in the area.[24]

The Maratha army was a mix of Rohillas, Rajputs, and Marathas. It also included a small force of the Portuguese under their officer, de Pinto.[24] The left flank of the Maratha army, commanded by Moropant Dixit and Raste, was stationed on the flat ground on which the University of Pune stands today.[24] The centre was commanded by Bapu Gokhale and the right was under Vinchurkar. British troop movements began on 1 November 1817 when Colonel Burr moved his forces towards what is now Bund Garden via the Holkar Bridge.[36] The Maratha were successful initially in creating and exploiting a gap in the British left and centre. These successes were nullified by the Maratha horses being thrown into disarray by a hidden canal and the temporary loss of command by Gokhale, whose horse was shot. The Marathas were rendered leaderless when Moropant Dixit on the right was shot dead. The British infantry advanced steadily, firing volley after volley, causing the Maratha cavalry to retreat in a matter of four hours. The British soon claimed victory. The British lost 86 men and the Maratha about 500.[37][38]

The Pindaris

After the second Anglo-Maratha war, Shinde and Holkar had lost many of their territories to the British. They encouraged the Pindaris to raid the British territories.[39] The Pindaris, who were mostly cavalry, came to be known as the Shindeshahi and the Holkarshahi after the patronage they received from the respective defeated Maratha leaders.[32] The Pindari leaders were Setu, Karim Khan, Dost Mohammad, Tulsi, Imam Baksh, Sahib Khan, Kadir Baksh, Nathu, and Bapu. Of these, Setu, Karim Khan, and Dost Mohammad belonged to Shindeshahi and the rest to Holkarshahi.[40] The total strength of the Pindaris in 1814 was estimated at 33,000.[39] The Pindaris frequently raided villages in Central India. The result of the Pindari raids was that Central India was being rapidly reduced to the condition of a desert because the peasants were unable to support themselves on the land. They had no option but to join the robber bands or starve.[41] In 1815, 25,000 Pindaris entered the Madras Presidency and destroyed over 300 villages on the Coromandel coast. Another band swept the Nizam's kingdom while a third entered Malabar. Other Pindari raids on British territory followed in 1816 and 1817. Francis Rawdon-Hastings saw that there could not be peace or security in India until the predatory Pindaris were extinguished.[42]

British planning

To lead an army against the Pindaris in the hope of engaging them in a regular battle was not possible. To effectively crush the Pindaris, they would have to be surrounded so that they could have no means of escape.[42] Francis Rawdon-Hastings obtained authority from the British government to take action against the Pindaris[41] while performing diplomacy with the principal Maratha leaders to act in concert with him. The Pindaris continued to have the sympathy of almost all the Maratha leaders. In 1817 Rawdon-Hastings collected the strongest British army which had yet been seen in India, numbering roughly 120,000 men. The army was assembled from two smaller armies, the Grand Army or Bengal army in the north under his personal command, and the Army of the Deccan under General Hislop in the south.[43] The British plan was to normalize relations with the Shinde, Holkar, and Amir Khan. The three were known to be well disposed towards the Pindaris and harboured them in their territories. Shinde was secretly planning with the Peshwa and the Nepal Ministry to form a coalition against the British. His correspondence with Nepal was intercepted and presented to him in Durbar.[44] He was forced to enter into a treaty by which he pledged to assist the British against the Pindaris and to prevent any new gangs being formed in his territory. Diplomacy, pressure, and the treaty of Gwalior kept Shinde out of the war. Amir Khan disbanded his army on condition of being guaranteed the possession of the principality of Tonk in Rajputana. He sold his guns to the British and agreed to prevent predatory gangs from operating from his territory.[44] The army for the war was composed of two armies, the Grand Army or the Bengal Army with a strength of 40,000 troops and the Army of the Deccan with a strength of 70,400. The Grand Army was divided into three divisions and a reserve. The left division was led by Major General Marshall and the central division was under Francis Rawdon-Hastings. The reserve was under General Ochterlony.[45] The second army, the Army of the Deccan was composed of five divisions. The divisions were led by General Hislop, Brigadier General Doveton, General Malcolm, Brigadier General Smith, Lieutenant Colonel Adams. The Army of Deccan comprised 70,400 troops, bringing the total strength of the entire composite British East India Company army to 110,400.[46] In addition the Madras and Pune residencies each had two battalions and a detail of an artillery unit. The Madras residency had an additional three troops of the 6th Bengal Cavalry.[47] In October and early November, the first division of the Grand Army was sent to Sind, the second to Chambal, the third to Eastern Narmada. The reserve division was used to pressurise Amir Khan. The effect of the dispatching of the first and second divisions was to cut off Shinde from his potential allies. He and Amir Khan were thus pressured into signing a treaty.[47]

The first and third division of the army of the Deccan were concentrated at Harda to hold the fords of the Narmada. The second division was used placed at Malkapur to keep a watch on the Berar Ghats. The fourth division marched to Khandesh occupying the region between Pune and Amravati (Berar) administrative divisions whereas the fifth division was placed at Hoshangabad and the reserve division was placed between the Bhima and Krishna rivers.[48]

Attack on the Pindaris

The attack on the Pindaris was carried out as planned. The Pindaris were attacked, and their homes were surrounded and destroyed. General Hislop from the Madras Residency attacked the Pindaris from the south and drove them beyond the Narmada river, where governor general Francis Rawdon-Hastings was waiting with his army.[49] Karim Khan surrendered to the British and was given lands in Gorakhpur.[50] The principal routes from Central India were occupied by British detachments. The Pindari forces were completely broken up, scattered in the course of a single campaign. They made no stand against the regular troops, and even in small bands they were unable to escape the ring of forces drawn around them. The Pindaris rapidly dispersed over the country. The Pindari chiefs were reduced to the condition of hunted outlaws. The desperate Pindaris expected the Marathas to help them, but none dared to give them even a place of shelter for their families. Karim and Setu had still 23,000 men between them but such a force was no match for the armies that surrounded them. In whatever direction they turned they were met by British forces. Defeat followed defeat. One gang made their escape to the south, leaving all their baggage behind them. Many fled to the jungles and perished. Others sought refuge in the villages, but were killed without mercy by the villagers who had not forgotten the sufferings they had been inflicted upon by the Pindaris.[49] The Pindari chiefs Karim Khan and Wasil Mohammed had been present with their Durras at the battle of Mahidpur. Since by this time the Maratha powers had been reduced significantly, the pursuit of Setu and the other leaders was resumed with vigor. All the leaders had surrendered before the end of February and the Pindari system and power was brought to a close. They were removed to Gorakhptir where they obtained grants of land for their subsistence. Karim Khan became a farmer on the small estate he received beyond the Ganges in Gorakpur. Wasil Mohammed attempted to escape. He was found and committed suicide by taking poison.[51] Setu, a Jat by caste,[52] was hunted by John Malcolm from place to place until he had no followers left. He vanished into the jungles of Central India in 1819[53] and was killed by a tiger.[50][note 6]

Flight of the Peshwa

On the orders of Elphinstone, General Smith arrived in Yerwada near Pune on 13 November at the site of the present Deccan College.[36] Smith and his troops crossed the river on 15 November and took up positions at Ghorpadi. On the morning of 16 November, the Marathas were engaged in a battle with the British. While the Maratha generals such as Purandare, Raste, and Bapu Gokhale were ready to advance on to the British forces, they were demoralized after learning that the Peshwa and his brother had fled to Purandar. A force of 5,000 additional Marathas was located at the confluence of two rivers—the Mula and the Mutha—under the leadership of Vinchurkar, but they remained idle. Bapu Gokhale retreated to guard the Peshwa in flight. The next morning, General Smith advanced towards the city of Pune and found that the Peshwa had fled towards the city of Satara.[55] During the day Pune surrendered, and great care was taken by General Smith for the protection of the peaceful part of the community. Order was soon re-established.[55] The British forces entered Shanivar Wada on 17 November and the Union flag was hoisted by Balaji Pant Natu. However the saffron flags of the Peshwa were not removed from Kotwali Chavdi until the defeat of Baji Rao at Ashti; it might seem that the British still believed that the war was not raised by Baji Rao but he was forced to do so under pressure from Bapu Gokhle, Trimabkji Dengle and Moreshwar Dikshit. [56][57]

The Peshwa now fled to the town of Koregaon. The Battle of Koregaon (also known as the battle of Koregaon Bhima) took place on 1 January 1818 on the banks of the river Bhima, north west of Pune. Captain Stauton arrived near Koregaon along with 500 infantry, two six-pounder guns, and 200 irregular horsemen. Only 24 of the infantry were of European origin; they were from the Madras Artillery. The rest of the infantry was composed of Indians employed by the British.[36] The village of Koregaon was on the north bank of the river, which was shallow and narrow at this time of year. The village had a fortified enclosure constructed in the standard Maratha fashion. Stauton occupied the village but was unable to take the fortified enclosure, which was occupied by the Marathas. The British were cut off from the river, their only source of water. A fierce battle ensued that lasted the entire day. Streets and guns were captured and recaptured, changing hands several times. Baji Rao's commander Trimabkji killed Lt. Chishom thereby avenging the death of Govindrao Gokhle, the only son of Bapu Gokhle. [58] The Peshwa watched the battle from atop a nearby hill about two miles away. The Marathas evacuated the village and retreated during the night. The British lost 175 men and about a third of the irregular horse, with more than half of the European officers wounded. The Marathas lost 500 to 600 men.[59] When the British found the village evacuated in the morning, Staunton took his battered troops and pretended to march on to Pune, but actually went to Shirur. The first authentic information about the Koregaon battle shows that it was a narrow escape rather than a heroic victory for the British. "Accounts have been received from Lt Col Burr, dated the 3rd(January, 1818), intimating that Capt. Staunton, commanding the 2nd battalion 1st regiment of Bombay Native Infantry, had been fortunately able to commence his march back to Seroor, with 125 wounded, having buried 50 at Goregaum (sic), and left 12 or 15 there, badly wounded; that the Peshwa had proceeded Southward, General Smith in pursuit, which had probably saved the battalion." [60]

After the battle the British forces under general Pritzler[59] pursued the Peshwa, who fled southwards towards Karnataka with the Raja of Satara.[59] The Peshwa continued his flight southward throughout the month of January.[61][62] Not receiving support from the Raja of Mysore, the Peshwa doubled back and passed General Pritzler to head towards Solapur.[62] Until 29 January the pursuit of the Peshwa had not been productive. Whenever Baji Rao was pressed by the British, Gokhale and his light troops hovered around the Peshwa and fired long shots. Some skirmishes took place, and the Marathas were frequently hit by shells from the horse artillery. There was, however, no advantageous result to either party.[63] On 7 February General Smith entered Satara and captured the royal palace of the Marathas. He symbolically raised the British flag.[63] The next day, the Bhagwa Zenda —the flag of Shivaji and the Marathas— was raised in its place.[63] To gain the support of the population, the British declared that they would not interfere with the tenets of any religion. They announced that all Watans, Inams,[note 7] pensions, and annual allowances would be continued provided that the recipients withdrew from the service of Baji Rao.[63] During this time Baji Rao remained in the vicinity of Solapur.[65]

On 19 February, General Smith got word that the Peshwa was headed for Pandharpur. General Smith's troops attacked the Peshwa at Ashti en route. During this battle, Gokhale died while defending the Peshwa from the British. The Raja of Satara was captured along with his brother and mother. The Maratha king, first imprisoned by Tarabai in the 1750s had lost power much earlier but was reinstated by Madhav rao Peshwa in 1763 after Tarabai's death. Since then the king had retained a titular position of appointing the Peshwas. The Emperor Alamgir II in his farman to the Peshwa had complimented them for looking after the Chhatrapati family.[66] The Chhatrapati declared in favour of the British and this ended the Peshwa's legal position as head of the Maratha confederacy, this was done by a jahirnama which stated Peshwas were no longer the head of the Maratha confederacy. However Baji Rao II challenged the jahirnama of removing him from his position as Peshwa by issuing another jahirnama removing Mountstuart Elphinstone as British Resident to his state. The death of Gokhale and the skirmish at Ashti hastened the end of the war.[67] Soon after this Baji Rao was deserted by the Patwardhans.[68]

By 10 April 1818, General Smith's forces had taken the forts of Sinhagad and Purandar.[69] Mountstuart Elphinstone mentions the capture of Sinhagadh in his diary entry for 13 February 1818: "The garrison contained no Marathas, but consisted of 100 Arabs, 600 Gosains, and 400 Konkani. The Killadar was a boy of eleven; the real Governor, Appajee Punt Sewra, a mean-looking Carcoon. The garrison was treated with great liberality; and, though there was much property and money in the place, the Killadar was allowed to have whatever he claimed as his own."[69][note 8] On 3 June 1818 Baji Rao surrendered to the British and negotiated the sum of ₹ eight lakhs as annual maintenance.[71] Baji Rao obtained promises from the British in favor of the Jagirdars, his family, the Brahmins, and religious institutions.[71] The Peshwa was sent to Bithur near Kanpur.[72] While the downfall and banishment of the Peshwa was mourned all over the Maratha Empire as a national defeat, the Peshwa seemed unaffected. He contracted more marriages and spent his long life engaged in religious performances and excessive drinking.[73]

Events in Nagpur

Madhoji Bhonsle, also known as Appa Saheb, consolidated his power in Nagpur after the murder of his cousin, the imbecile ruler Parsoji Bhonsle. He entered into a treaty with the British on 27 May 1816.[56] He ignored the request of the British Resident Jenkins to refrain from contact with Baji Rao II. Jenkins asked Appa Saheb to disband his growing concentration of troops and come to the residency, which he also refused to do. Appa Saheb openly declared support for the Peshwa, who was already fighting the British near Pune. As it was now clear that a battle was in the offing, Jenkins asked for reinforcements from nearby British East India Company troops. He already had about 1,500 men under Lieutenant-Colonel Hopentoun Scott.[74] Jenkins sent word for Colonel Adams to march to Nagpur with his troops.[56] Like other Maratha leaders, Appa Shaeb employed Arabs in his army.[75] They were typically involved in holding fortresses. While they were known to be among the bravest of troops, they were not amenable to discipline and order. The total strength of the Marathas was about 18,000.[76]

The Residency was to the west of the Sitabardi hill, a 300-yard (270 m) hillock running north–south. The British East India Company troops occupied the north end of the hillock.[77] The Marathas, fighting with the Arabs, made good initial gains by charging up the hill and forcing the British to retreat to the south. British commanders began arriving with reinforcements: Lieutenant Colonel Rahan on 29 November, Major Pittman on 5 December, and Colonel Doveton on 12 December. The British counterattack was severe and Appa Saheb was forced to surrender. The British lost 300 men, of which 24 were Europeans; the Marathas lost an equal number. A treaty was signed on 9 January 1818. Appa Saheb was allowed to rule over nominal territories with several restrictions. Most of his territory, including the forts, was now controlled by the British. They built additional fortifications on Sitabardi hill.[77]

A few days later Appa Saheb was arrested. He was being escorted to Allahabad when he escaped to Punjab to seek refuge with the Sikhs. They turned him down and he was captured once again by the British near Jodhpur. Raja Mansingh of Jodhpur stood surety for him and he remained in Jodhpur, where he died on 15 July 1849 at 44 years of age.[77]

Subjugation of Holkar

Holkar was offered terms similar to those offered to Shinde; the only difference was that Holkar accepted and respected the independence of Amir Khan. The Court of Holkar was at this time practically nonexistent. When Tantia Jog, an official of the Holkar, urged acceptance of the offer he was suspected of being in collusion with the British. In reality he made the suggestion because he was aware of the power of the British as he had seen their armies in action when he had commanded a battalion in the past.[78] Holkar responded to the Peshwa's call for insurrection against the British by initiating a battle in Mahidpur.[79]

The battle of Mahidpur between Holkar and the British was fought on 21 December 1817. The charge on the British side was led by Malcolm himself. A deadly battle ensued lasting from midday until 3:00 am. Lieutenant General Thomas Hislop was commander in chief of the Madras army. Hislop came in sight of the Holkar army about 9:00 am.[80] The British East India Company's army lost 800 men[35] but Holkar's force was destroyed.[81] The British East India Company's losses were 800 killed or wounded but Holkar's loss was much larger with about 3,000 killed or wounded.[51] These losses meant Holkar was deprived of any means of rising in arms against the British,[82] and this broke the power of the Holkar dynasty. The battle of Mahidpur proved disastrous for the Maratha fortunes. Henry Durand wrote, "After the battle of Mahidpur not only the Peshwa's but the real influence of the Mahratta States of Holkar and Shinde were dissolved and replaced by British supremacy."[83] Although the power of the Holkar family was broken, the remaining troops remained hostile and a division was retained to disperse them. The ministers made overtures of peace,[51] and on 6 January 1818 the Treaty of Mandeswar was signed;[49] Holkar accepted the British terms in totality.[82] Holkar came under British authority as an independent prince subject to the advice of a British Resident.[49]

End of the war and its effects

At the end of the war, all of the Maratha powers had surrendered to the British. Shinde and the Afghan Amir Khan were subdued by the use of diplomacy and pressure, which resulted in the Treaty of Gwailor[84] on 5 November 1817. Under this treaty, Shinde surrendered Rajasthan to the British and agreed to help them fight the Pindaris. Amir Khan agreed to sell his guns to the British and received a land grant at Tonk in Rajputana.[44] Holkar was defeated on 21 December 1817 and signed the Treaty of Mandeswar[49] on 6 January 1818. Under this treaty the Holkar state became subsidiary to the British. The young Malhar Rao was raised to the throne.[85][86] Bhonsle was defeated on 26 November 1817 and was captured but he escaped to live out his life in Jodhpur.[85][87] The Peshwa surrendered on 3 June 1818 and was sent off to Bithur near Kanpur under the terms of the treaty signed on 3 June 1818.[88] Of the Pindari leaders, Karim Khan surrendered to Malcolm in February 1818; Wasim Mohammad surrendered to Shinde and eventually poisoned himself; and Setu was killed by a tiger.[86][41][89]

The war left the British, under the auspices of the British East India Company, in control of virtually all of present-day India south of the Sutlej River. The famed Nassak Diamond was seized by the Company as part of the spoils of the war.[90] The British acquired large chunks of territory from the Maratha Empire and in effect put an end to their most dynamic opposition.[91] The terms of surrender Malcolm offered to the Peshwa were controversial amongst the British for being too liberal: The Peshwa was offered a luxurious life near Kanpur and given a pension of about 80,000 pounds. A comparison was drawn with Napoleon, who was confined to a small rock in the south Atlantic and given a small sum for his maintenance. Trimbakji Dengale was captured after the war and was sent to the fortress of Chunarin Bengal where he spent the rest of his life. With all active resistance over, John Malcolm played a prominent part in capturing and pacifying the remaining fugitives.[92]

The Peshwa's territories were absorbed into the Bombay Presidency and the territory seized from the Pindaris became the Central Provinces of British India. The princes of Rajputana became symbolic feudal lords who accepted the British as the paramount power. Thus Francis Rawdon-Hastings redrew the map of India to a state which remained more or less unaltered until the time of Lord Dalhousie.[93] The British brought an obscure descendant of Shivaji, the founder of the Maratha Empire, to be the ceremonial head of the Maratha Confederacy to replace the seat of the Peshwa. An infant from the Holkar family was appointed as the ruler of Nagpur under British guardianship. The Peshwa adopted a son, Nana Sahib, who went on to be one of the leaders of the Rebellion of 1857.[93] After 1818, Montstuart Elphinstone reorganized the administrative divisions for revenue collection,[94] thus reducing the importance of the Patil, the Deshmukh, and the Deshpande.[95] The new government felt a need to communicate with the local Marathi-speaking population; Elphinstone pursued a policy of planned standardization of the Marathi language in the Bombay Presidency starting after 1820.[96]

See also

- Maratha Empire

- First Anglo-Maratha War

- Second Anglo-Maratha War

- List of Maratha dynasties and states

- British Empire

- British Raj

- History of India

- Shivaji

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ "Thus, many Pindaris were originally Muslim or Maratha cavalrymen who were disbanded or found Pindari life better than formal military service... Most Pindaris professed to be Muslims, but some could not even repeat the kalima or Muslim creed nor knew the name of the prophet."[3]

- ^ Meaning "Administrator of the Realm", the title of Nizam was specific to the native sovereigns of Hyderabad State, India, since 1719.[8]

- ^ This treaty, as Grant Duff says, occasioned infinite discussions amongst the British in India and in Europe, and started the First Maratha War.[15]

- ^ With justifiable pride Hastings wrote to one of his friends on 7 February 1783: "Indeed, my dear Sir, there have been three or four very critical periods in our affairs in which the existence of the Company and of the British dominion in India lay at my mercy and would have been lost had I coldly attended to the beaten path of duty and avoided personal responsibility. In the redress afforded to the Nizam I drew him to our interests from the most inveterate enmity. In my negotiations with Modajee Boosla (sic) I preserved these provinces from ravage and obtained evidence of his connections even beyond his own intentions; and I effected a peace and alliance with Madajee Sindhia (sic) which was in effect a peace with the Maratha State."[17]

- ^ "Opposed to these were the British who had come all the way from England to establish an empire in India. They had a (sic) previous experience not only in many European wars, but also in many Indian ones. Whatever they did, they did in a planned manner. No step was taken blindly. Everything was thoroughly discussed and debated upon before it was taken up. The network of their spies spread far and wide. They mastered the Indian languages to deal with the Indians in a perfect manner. They mastered Indian geography before they made any military movement in any part of the country. Nothing was left to chance and guess-work."[19]

- ^ Chithu is referred to as Setu in Marathi.[39] "So the famous Chithu, the Pindari chieftain, who, wandering alone in the jungle on the banks of the Tapti River after the defeat and dispersal of his robber horde in 1818, fell a victim to a man-eating tiger, his remains being identified by the discovery of his head and a satchel containing his papers in the tiger's lair."[54]

- ^ Watans and Inams were the properties or lands of the absentee landlords, mostly the high caste Brahmins. Watan and Inam are terms specific to Maharasthra. Jagir is another such term in Maharashtra. Someone who held a Watan was called Watandar; a holder of an inam was an Inamdar. Zamindar is a similar term used in the state of Bengal. Watans and Inams were abolished in independent India.[64]

- ^ Killadar means the commandant of a fort, castle or garrison.[70]

Citations

- ^ "Maratha Wars". Britannica Encyclopædia.

- ^ a b Bakshi & Ralhan 2007, p. 261.

- ^ McEldowney 1966, p. 18.

- ^ Naravane 2006, pp. 79–86.

- ^ Black 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Subburaj 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Sen 1994, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Sen 1994, p. 2.

- ^ a b Sen 1994, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Sen 1994, p. 4.

- ^ Sen 1994, pp. 4–9.

- ^ Sen 1994, p. 9.

- ^ Sen 1994, p. 10.

- ^ Sen 1994, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Sen 1994, p. 11.

- ^ a b Schmidt 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Sen 1994, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Sen 1994, p. 17.

- ^ a b Chhabra 2005, p. 40.

- ^ a b Sen 1994, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Chhabra 2005, p. 39.

- ^ a b Naravane 2006, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Chhabra 2005, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Naravane 2006, p. 80.

- ^ Duff 1921, pp. 468–469.

- ^ a b c Duff 1921, p. 468.

- ^ a b c Duff 1921, p. 470.

- ^ Duff 1921, p. 474.

- ^ a b Duff 1921, p. 471.

- ^ Burton 1908, p. 153.

- ^ United Service Institution of India 1901, p. 96.

- ^ a b Naravane 2006, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Nadkarni 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Black 2006, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Sarkar & Pati 2000, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f Naravane 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Murray 1901, p. 324.

- ^ Chhabra 2005, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Naravane 2006, p. 86.

- ^ Naravane 2006, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Russell 1916, p. 396.

- ^ a b Sinclair 1884, p. 194.

- ^ Bakshi & Ralhan 2007, p. 259.

- ^ a b c Sinclair 1884, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Bakshi & Ralhan 2007, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Bakshi & Ralhan 2007, pp. 259–262.

- ^ a b United Service Institution of India 1901, p. 101.

- ^ United Service Institution of India 1901, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d e Sinclair 1884, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b Hunter 1909, p. 495.

- ^ a b c Keightley 1847, p. 165.

- ^ Travers 1919, p. 19.

- ^ Sinclair 1884, p. 196.

- ^ Burton 1936, pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b Duff 1921, p. 482.

- ^ a b c Naravane 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Rao 1977, p. 135.

- ^ Naravane 2006, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Duff 1921, p. 487.

- ^ "Interesting Intelligence from the London Gazette" (June 1818) page 550.

- ^ Duff 1921, p. 483.

- ^ a b Duff 1921, p. 488.

- ^ a b c d Duff 1921, p. 489.

- ^ Government of Maharashtra 1961.

- ^ Duff 1921, p. 491.

- ^ Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan mandal Quarterly July 1920

- ^ Duff 1921, p. 493.

- ^ Duff 1921, p. 494.

- ^ a b Duff 1921, p. 517.

- ^ Yule & Burnell 1903, p. 483.

- ^ a b Duff 1921, p. 513.

- ^ Duff 1921, pp. 513–514.

- ^ Chhabra 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Burton 1908, p. 159.

- ^ Burton 1908, p. 53.

- ^ Burton 1908, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Naravane 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Kibe 1904, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Bakshi & Ralhan 2007, p. 315.

- ^ Hough 1853, p. 71.

- ^ Prakash 2002, p. 135.

- ^ a b Prakash 2002, p. 136.

- ^ Government of Madhya Pradesh 1827, p. 79.

- ^ Prakash 2002, p. 300.

- ^ a b Dutt 1908, p. 173.

- ^ a b Lethbridge 1879, p. 193.

- ^ Lethbridge 1879, p. 192.

- ^ Dutt 1908, p. 174.

- ^ Dutt 1908, p. 172.

- ^ United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals 1930, p. 121.

- ^ Black 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Hunter 1907, p. 204.

- ^ a b Hunter 1907, p. 203.

- ^ Kulkarni 1995, p. 98.

- ^ Kulkarni 1995, pp. 98–99.

- ^ McDonald 1968, pp. 589–606.

References

- Bakshi, S.R; Ralhan, O.P. (2007), Madhya Pradesh Through the Ages, New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, ISBN 978-81-7625-806-7

- Black, Jeremy (2006), A Military History of Britain: from 1775 to the Present, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-99039-8

- Yule, Sir Henry; Burnell, Arthur Coke (1903), William Crooke (ed.), Hobson-Jobson: a Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive, London: J. Murray, OCLC 4718658

- Burton, Reginald George (1908), Wellington's Campaigns in India, Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India, OCLC 13082193

- Burton, Reginald George (1936), The Tiger Hunters, London: Hutchinson, OCLC 6338833

- Chhabra, G.S. (2005), Advance Study in the History of Modern India, vol. Volume 1: 1707–1803, New Delhi: Lotus Press, ISBN 81-89093-06-1

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Duff, James Grant (1921), Stephen Meredyth Edwardes (ed.), A History of the Mahrattas, vol. 2, London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, OCLC 61585379

- Dutt, Romesh Chunder (1908), A Brief History of Ancient and Modern India According to the Syllabus Prescribed by the Calcutta University, Calcutta: S.K. Lahiri & Company

- Finn, Margot C. "Material turns in British history: I. Loot." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 28 (2018): 5-32. online

- Government of Madhya Pradesh (1827), District Gazetteers: Indore Gazetteer of India, vol. Volume 17 of Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers, Madhya Pradesh (India), Bhopal: Government Central Press

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Government of Maharashtra (1961), Land Acquisition Act (PDF), Bombay

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hough, William (1853), Political and Military Events in British India: From the Years 1756 to 1849, vol. Volume 1 Political and Military Events in British India: From the Years 1756 to 1849, London: W.H. Allen & Company, hdl:2027/mdp.39015026640402, OCLC 5105166

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Hunter, Sir William Wilson (1907), A Brief History of the Indian Peoples, Oxford: Clarendon Press, hdl:2027/uc1.$b196576, OCLC 464656679

- Hunter, Sir William Wilson (1909), James Sutherland Cotton; Sir Richard Burn; Sir William Stevenson Meyer (eds.), Imperial Gazetteer of India., vol. Volume 2 of Imperial Gazetteer of India, Great Britain. India Office Gazetteers of British India, 1833–1962, Oxford: Clarendon Press

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Murray, John (1901), A Handbook for Travellers in India, Burma, and Ceylon, Calcutta: John Murray, OCLC 222574206

- Keightley, Thomas (1847), A History of India: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, London: Whittaker

- Kibe, Madhav Rao Venayek (1904), The Calcutta Review, vol. 119, Calcutta; London, retrieved September 10, 2010

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kulkarni, Sumitra (1995), The Satara Raj, 1818–1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture, New Delhi: Mittal Publications, ISBN 978-81-7099-581-4

- Lethbridge, Sir Roper (1879), History of India, Calcutta: Brown & Co., OCLC 551701397

- McDonald, Ellen E. (1968), The Modernizing of Communication: Vernacular Publishing in Nineteenth Century Maharashtra, Berkeley: University of California Press, OCLC 483944794

- McEldowney, Philip F (1966), Pindari Society and the Establishment of British Paramountcy in India, Madison: University of Wisconsin, OCLC 53790277

- Nadkarni, Dnyaneshwar (2000), Husain: Riding The Lightning, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-676-5

- Naravane, M. S. (2006). Battles of the Honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3.

- Prakash, Om (2002), Encyclopaedic History of Indian Freedom Movement, New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 978-81-261-0938-8

- Rao, S. Venugopala (1977), Power and Criminality: a Survey of Famous Crimes in Indian History, Bombay: Allied Publishers, OCLC 4076888

- Russell, Robert Vane (1916), The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India: pt. II. Descriptive Articles on the Principal Castes and Tribes of the Central Provinces, vol. Volume 4 of The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, OCLC 8530841

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sarkar, Sumit; Pati, Biswamoy (2000), Biswamoy Pati (ed.), Issues in Modern Indian History: for Sumit Sarkar, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-658-9

- Schmidt, Karl J. (1995), An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1-56324-334-9

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1994), Anglo-Maratha Relations, 1785–96, vol. Volume 2 of Anglo-Maratha Relations, Sailendra Nath Sen, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-789-0

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sinclair, David (1884), History of India, Madras: Christian Knowledge Society's Press

- Subburaj, V.V.K (2000), RRB Technical Cadre, Chennai: Sura Books, ISBN 81-7254-011-6

- Travers, John (1919), Comrades in Arms – A War Book for India, Bombay: Oxford University Press, OCLC 492678532

- United Service Institution of India (1901), Journal of the United Service Institution of India, vol. 30, retrieved September 26, 2010

- United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (1930), Court of Customs and Patent Appeals Reports, vol. 18, Washington: Supreme Court of the United States, OCLC 2590161

Further reading

- Sarkar, Sir Jadunath (1919), Shivaji and His Times, Calcutta: MC Sarkar & Sons, pp. 482–85, OCLC 459363111

- Mehta, J. L (2005), Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707–1813, Berkshire, UK; Elgin, Ill.: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6