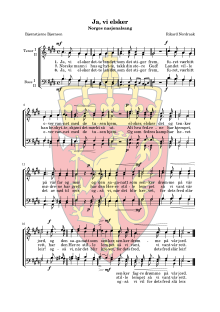

Ja, vi elsker dette landet

| English: Yes, we love | |

|---|---|

| |

National anthem of | |

| Lyrics | Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, c. 1859–1868 |

| Music | Rikard Nordraak, 1864 |

| Published | 17 May 1864 |

| Adopted | 1864 (de facto) 11 December 2019 (de jure) |

| Preceded by | "Sønner av Norge" |

| Audio sample | |

"Ja, vi elsker" (instrumental, one verse) | |

"Ja, vi elsker dette landet" (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈjɑː viː ˈɛ̀lskə ˈɖɛ̀tːə ˈlɑ̀nːə] ; Template:Lang-en) is the Norwegian national anthem. Originally a patriotic song, it came to be commonly regarded as the de facto national anthem of Norway in the early 20th century, after being used alongside "Sønner av Norge" since the 1860s. It was officially adopted in 2019.[1] The lyrics were written by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson between 1859 and 1868, and the melody was written by his cousin Rikard Nordraak sometime during the winter of 1863 and 1864. It was first performed publicly on 17 May 1864 in connection with the 50th anniversary of the constitution. Usually only the first and the last two verses are sung.

History

Until the mid-1860s, the songs "Sønner av Norge" and "Norges Skaal" were commonly regarded as the Norwegian national anthems, with "Sønner av Norge" being most recognised. "Ja, vi elsker dette landet" gradually came to be recognised as a national anthem from the mid-1860s. Until the early 20th century, however, both "Sønner av Norge" and "Ja, vi elsker" were used, with "Sønner av Norge" preferred in official situations. In 2011, the song "Mitt lille land" featured prominently in the memorial ceremonies following the 2011 Norway attacks and was described by the media as "a new national anthem".[2] On Norwegian Constitution Day in 2012, the NRK broadcast was opened with "Mitt lille land".[3]

Background

Norway did not have an official national anthem until 11 December 2019, but over the last 200 years, a number of songs have been commonly regarded as de facto national anthems. At times, multiple songs have enjoyed this status simultaneously. "Ja, vi elsker dette landet" is now most often recognized as the anthem, but until the early 20th century, "Sønner av Norge" occupied this position.

In the early 19th century, the song "Norges Skaal" was regarded by many as a de facto national anthem. From 1820, the song "Norsk Nationalsang" (lit. '"Norwegian National Song"') became the most recognised national anthem. It came to be known as "Sønner av Norge" (originally "Sønner af Norge"), after its first stanza. "Sønner av Norge" was written by Henrik Anker Bjerregaard (1792–1842) and the melody by Christian Blom (1782–1861), after the Royal Norwegian Society for Development had announced a competition to write a national anthem for Norway in 1819. "Norsk Nationalsang" ("Sønner af Norge") was announced as the winner.[4][5][6] "Blant alle Lande" (also called "Nordmandssang") by Ole Vig has also been used as a national anthem. Henrik Wergeland also wrote an anthem originally titled "Smaagutternes Nationalsang" ("The Young Boys' National Anthem") and commonly known as "Vi ere en Nation, vi med".

"Ja, vi elsker dette landet" was written by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and composed by Rikard Nordraak between 1859 and 1868, and gradually came to replace "Sønner av Norge" as the most recognised national anthem. Until the early 20th century, "Sønner av Norge" and "Ja, vi elsker dette landet" were used alongside each other, but "Sønner av Norge" was preferred in official settings. Since 2011, the anthem Mitt lille land by Ole Paus has also been called a "new national anthem" and notably featured in the memorial ceremonies following the 2011 Norway attacks.[7] On Norwegian Constitution Day in 2012, the NRK broadcast opened with "Mitt lille land."[8]

In addition, Norway has an unofficial royal anthem, "Kongesangen", based on "God Save the King" and written in its modern form by Gustav Jensen. The psalm "Gud signe vårt dyre fedreland", written by Elias Blix and with a melody by Christoph Ernst Friedrich Weyse, is often called Norway's "national psalm".

Lyrics and translation

Bjørnson wrote in a modified version of the Danish language current in Norway at the time. Written Bokmål has since then been altered in a series of orthographic reforms intended to distinguish it from Danish and bring it closer to spoken Norwegian. The text below, and commonly in use today, is identical to Bjørnson's original in using the same words, but with modernised spelling and punctuation. The most sung verses—1, 7 and 8 (which are highlighted and in bold)—have been modernised most and have several variations in existence. For example, Bjørnson originally wrote «drømme på vor jord», which some sources today write as «drømme på vår jord», while others write «drømmer på vår jord».

In each verse the last two lines are sung twice, and one or two words are repeated an extra time when the lines are sung the second time (for example "senker" in the first verse). These words are written in italics in the Norwegian lyrics below. The first verse is written down in full as an example.

| Original | Literal translation |

|---|---|

I

| |

Ja, vi elsker dette landet, |

Yes, we love this country |

II

| |

Dette landet Harald berget |

|

III

| |

Bønder sine økser brynte |

Farmers their axes sharpened |

IV

| |

Visstnok var vi ikke mange, |

Sure, we were not many |

V

| |

Hårde tider har vi døyet, |

|

VI

| |

Fienden sitt våpen kastet, |

The enemy threw away his weapon, |

VII

| |

Norske mann i hus og hytte, |

Norwegian man in house and cabin, |

VIII

| |

Ja, vi elsker dette landet, |

Yes, we love this country |

Poetic translation and metric version

The three commonly used stanzas of Ja, vi elsker were translated into English long ago. The name of the translator is seldom mentioned in printed versions of the English text. It has so far not been possible to identify the translator or ascertain when it was translated. But the following versions of stanzas 1, 7, and 8 are well known and often sung by descendants of Norwegian immigrants to the United States. Its popularity and familiarity among Norwegian-Americans seems to indicate that it has been around for a long time, certainly since before the middle of the 20th century, and possibly much earlier. This translation may be regarded as the "official" version in English.

|

1 |

Yes, we love with fond devotion |

Metrical versions

Two alternative metrical versions also exist. The second follows the original closely, and was learnt by heart by a Norwegian[9] who did not know the translator's name. It was published (without the translator's name) in a collection of Sange og digte paa dansk og engelsk[10] [Songs and Poems in Danish and English]. There are two small changes in the text in this version, which is presented here. Verse 2, which is seldom sung, has been omitted, and the last two lines in each verse are repeated, in the same way as we sing it in Norwegian.

|

1 |

Norway, thine is our devotion, |

Yes, we love this land arising

Stormbeat o'er the sea With its thousand homes, enticing, Rugged though it be. Love it, love it, not forgetting Those we owe our birth, Nor that night of saga letting Down its dreams to earth, Nor that night of saga letting Down its dreams, its dreams, to earth. Norseman, where thou dwellest, render Praise and thanks to Him, Who has been this land's defender, When its hopes looked dim. Wars our fathers' aims unfolded, Tears our mothers shed, Roads of them for us He molded, To our rights they led. Roads of them for us He molded, To our rights, our rights, they led. Yes, we love this land arising Stormbeat o'er the sea With its thousand homes, enticing, Rugged though it be. Like our fathers who succeeded, Warring for release, So will we, whenever needed, Rally for its peace. So will we, whenever needed, Rally for its peace, its peace. |

Deleted verse a tribute to King Charles IV

A verse hailing Charles IV who had succeeded his father as king of Norway in July 1859 was included in the original version of "Ja, vi elsker". But after the divisive international events of the spring of 1864, when the ideal of a unified Scandinavia was shattered, Bjørnson went from being a monarchist to republicanism, and the tribute to the reigning sovereign was stricken from the song.

The lyrics that were taken out were:

- Kongen selv står stærk og åpen

- som vår Grænsevagt

- og hans allerbedste Våpen

- er vår Broderpagt.

In English this reads:

- The King himself stands strong and open

- As our border guard

- and his most powerful weapon

- is our brethren pact.

The "brethren pact" the text refers to was a military treaty between Norway, Sweden and Denmark to come to one another's assistance should one come under military assault. This happened when German troops invaded South Jutland in February 1864. None of the alliance partners came to Denmark's rescue. This perceived treason of the "brethren pact" once and for all shattered dreams of unification of the three countries.[11]

Controversies

In 1905 the Union between Sweden and Norway was dissolved after many years of Norwegian struggle for equality between the two states, as stipulated in the 1815 Act of Union. The unilateral declaration by the Norwegian Storting of the union's dissolution 7 June provoked strong Swedish reactions, bringing the two nations to the brink of war in the autumn. In Sweden, pro-war conservatives were opposed by the Social Democrats, whose leaders Hjalmar Branting and Zeth Höglund spoke out for reconciliation and a peaceful settlement with Norway. Swedish socialists sang Ja, vi elsker dette landet to demonstrate their support for the Norwegian people’s right to secede from the union.

During World War II, the anthem was used both by the Norwegian resistance and the Nazi collaborators, the latter mainly for propaganda reasons. Eventually, the German occupiers officially forbade any use of the anthem.

In May 2006, the multicultural newspaper Utrop proposed that the national anthem be translated into Urdu, the native language of the most numerous group of recent immigrants to Norway.[12] The editor's idea was that people from other ethnic groups should be able to honour their adopted country with devotion, even if they were not fluent in Norwegian. This proposal was referred to by other more widely read papers, and a member of the Storting called the proposal "integration in reverse".[13] One proponent of translating the anthem received batches of hate mail calling her a traitor and threatening her with decapitation.[14]

See also

References

- ^ https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Saker/Sak/?p=76439&target=case-status

- ^ Verdig tilstandsrapport fra nasjonalartistene Archived December 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, BT.no

- ^ Lindahl, Björn (2001-09-11). "Norsk festyra fick ny dimension" (in Swedish). Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ^ Sangen har lysning : studentersang i Norge på 1800-tallet, Anne Jorunn Kydland, 1995, ISBN 82-560-0828-8

- ^ Viktige trekk fra Norges vels historie 1809-1995, Kristian Kaus, 1996, ISBN 82-7115-100-2

- ^ Norsk litteraturkritikks historie 1770-1940, Bind 1, Edvard Beyer og Morten Moi, 1990, ISBN 82-00-06623-1

- ^ Verdig tilstandsrapport fra nasjonalartistene, BT.no

- ^ Björn Lindahl (2001-09-11). "Norsk festyra fick ny dimension" (in Swedish). Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ^ Torolv Hustad, born around 1930.

- ^ Volk, John, ed. (1903). Sange og digte paa dansk og engelsk. New York Public Library, digitized by Google: "Nordlysets" forlag. pp. 30–31.

- ^ Bomann-Larsen, Tor (2002). "Alt for Norge". Kongstanken. Haakon & Maud (in Norwegian). Vol. 1. Oslo, Norway: J.W. Cappelen. pp. 23–24. ISBN 82-02-19092-4.

- ^ Vil ha «Ja vi elsker» på urdu Archived May 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fr.p. sier nei til "Ja vi elsker" på urdu Archived May 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ http://oslopuls.no/nyheter/article1324897.ece. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link]

External links

- Sung May 1, 2005 in Salt Lake City Utah with Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Norwegian soprano Sissel Kyrkjebø; first stanza only and then in English