Gog and Magog

Gog and Magog (/ɡɒɡ/; /ˈmeɪɡɒɡ/; Template:Lang-he-n Gog u-Magog) in the Hebrew Bible may be individuals, peoples, or lands; a prophesied enemy nation of God's people according to the Book of Ezekiel, and one of the nations according to Genesis descended from Japheth son of Noah.

The Gog prophecy is meant to be fulfilled at the approach of what is called the "end of days", but not necessarily the end of the world. Jewish eschatology viewed Gog and Magog as enemies to be defeated by the Messiah, which will usher in the age of the Messiah. Christianity's interpretation is more starkly apocalyptic: making Gog and Magog allies of Satan against God at the end of the millennium, as can be read in the Book of Revelation.

To Gog and Magog were also attached a legend, certainly current by the Roman period, that they were people contained beyond the Gates of Alexander erected by Alexander the Great. Romanized Jewish historian Josephus knew them as the tribe descended from Magog the Japhethite, as in Genesis, and explained them to be the Scythians. In the hands of Early Christian writers they became apocalyptic hordes, and throughout the Medieval period variously identified as the Huns, Khazars, Mongols, or other nomads, or even the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

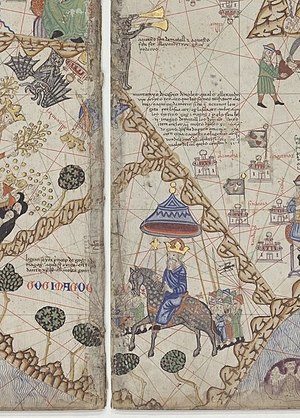

The legend of Gog and Magog and the gates were also interpolated into the Alexander Romances. In one version, "Goth and Magoth" are kings of the Unclean Nations, driven beyond a mountain pass by Alexander, and blocked from returning by his new wall. Gog and Magog are said to engage in human cannibalism in the romances and derived literature. They have also been depicted on Medieval cosmological maps, or Mappa mundi, sometimes alongside Alexander's wall.

Gog and Magog appear in the Quran as Yajuj and Majuj (Template:Lang-ar Yaʾjūj wa-Maʾjūj), adversaries of Dhul-Qarnayn, widely equated with Cyrus the Great and al-Iskanadar (Alexander the Great) in Islam. Muslim geographers identified them at first with Turkic tribes from Central Asia and later with the Mongols. In modern times they remain associated with apocalyptic thinking, especially in the United States and the Muslim world.

The names Gog and Magog

| Part of a series on |

| Eschatology |

|---|

The first mention of the two names occurs in the Book of Ezekiel, where Gog is an individual and Magog is his land; in Genesis 10 Magog is a person, son of Japheth son of Noah, but no Gog is mentioned. In Revelation, Gog and Magog together are the hostile nations of the world.[1][2] Gog or Goug the Reubenite[a] occurs in 1 Chronicles 5:4, but he appears to have no connection with the Gog of Ezekiel or Magog of Genesis.[4]

The form "Gog and Magog" may have emerged as shorthand for "Gog and/of the land of Magog", based on their usage in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible.[5] An example of this combined form in Hebrew (Gog u-Magog) has been found, but its context is unclear, being preserved only in a fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls.[b][6]

The meaning of the name Gog remains uncertain, and in any case the author of the Ezekiel prophecy seems to attach no particular importance to it; efforts have been made to identify him with various individuals, notably Gyges, a king of Lydia in the early 7th century, but many scholars do not believe he is related to any historical person.[7] The name Magog is equally obscure, but may come from the Assyrian mat-Gugu, "Land of Gyges", i.e., Lydia.[8] Alternatively, Gog may be derived from Magog rather than the other way round, and "Magog" may be code for Babylon.[c][9][10]

The Biblical "Gog and Magog" possibly gave derivation of the name Gogmagog, a legendary British giant.[d][11] A later corrupted folk rendition in print altered the tradition around Gogmagog and Corineus with two giants Gog and Magog, with whom the Guildhall statues came to be identified.[12]

Judeo-Christian texts

Ezekiel and the Old Testament

In the Old Testament, Gog only appears in chapters of the Book of Ezekiel.[e][14]

The Book records a series of visions received by the 6th-century BC prophet Ezekiel, a priest of Solomon's Temple, who was among the captive during the Babylonian exile. The exile, he tells his fellow captives, is God's punishment on Israel for turning away, but God will restore his people to Jerusalem when they return to him.[15] After this message of reassurance, chapters 38–39, the Gog oracle, tell how Gog of Magog and his hordes will threaten the restored Israel but will be destroyed, after which God will establish a new Temple and dwell with his people for a period of lasting peace (chapters 40–48).[16] The Gog oracle, as internal evidence indicates, was composed substantially later than the chapters around it.[f][17]

"Son of man, direct your face against Gog, of the land of Magog, the prince, leader of Meshech and Tubal, and prophesy concerning him. Say: Thus said the Lord: Behold, I am against you, Gog, the prince, leader of Meshech and Tubal ... Persia, Cush and Put will be with you ... also Gomer with all its troops, and Beth Togarmah from the far north with all its troops—the many nations with you."[18]

"Gog of Magog" here can be tied to Magog the Japhethite in Genesis 10, even though Gog's paternal lineage is not explicitly given, due to the string of other names present: Meshech, Tubal, Gomer are all sons of Japeth thus "brothers" of Magog; Togarmah of "Beth Togarmah" is Magog's "nephew".[19]

Of Gog's allies, Meshech and Tubal were 7th-century kingdoms in central Anatolia north of Israel, Persia towards east, Cush (Ethiopia) and Put (Libya) to the south; Gomer is the Cimmerians, a nomadic people north of the Black Sea, and Beth Togarmah was on the border of Tubal.[20] The confederation thus represents a multinational alliance surrounding Israel.[21] "Why the prophet's gaze should have focused on these particular nations is unclear," comments Biblical scholar Daniel I. Block, but their remoteness and reputation for violence and mystery possibly "made Gog and his confederates perfect symbols of the archetypal enemy, rising against God and his people".[22] One explanation is that the Gog alliance, a blend of the "Table of Nations" in Genesis 10 and Tyre's trading partners in Ezekiel 27, with Persia added, was cast in the role of end-time enemies of Israel by means of Isaiah 66:19, which is another text of eschatological foretelling.[23]

Although the prophecy refers to Gog as an enemy in some future, it is not clear if the confrontation is meant to occur in a final "end of days" since the Hebrew term aḥarit ha-yamim (Template:Lang-he-n) may merely mean "latter days", and is open to interpretation. Twentieth-century scholars have used the term to denote the eschaton in a malleable sense, not necessarily meaning final days, or tied to the Apocalypse.[g][24] Still, the Utopia of chapters 40–48 can be spoken of in the parlance of "true eschatological character, given that it is a product of "cosmic conflict" described in the immediately preceding Gog chapters.[25]

Gog and Magog from Ezekiel to Revelation

Over the next few centuries Jewish tradition changed Ezekiel's Gog from Magog into Gog and Magog.[27] The process, and the shifting geography of Gog and Magog, can be traced through the literature of the period. The 3rd book of the Sibylline Oracles, for example, which originated in Egyptian Judaism in the middle of the 2nd century BC,[28] changes Ezekiel's "Gog from Magog" to "Gog and Magog," links their fate with up to eleven other nations, and places them "in the midst of Aethiopian rivers"; this seems a strange location, but ancient geography did sometimes place Ethiopia next to Persia or even India.[29] The passage has a highly uncertain text, with manuscripts varying in their groupings of the letters of the Greek text into words, leading to different readings; one group of manuscripts ("group Y") links them with the "Marsians and Dacians", in eastern Europe, amongst others.[30]

The Book of Jubilees, from about the same time, makes three references to either Gog or Magog: in the first, Magog is a descendant of Noah, as in Genesis 10; in the second, Gog is a region next to Japheth's borders; and in the third, a portion of Japheth's land is assigned to Magog.[31] The 1st-century Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum, which retells Biblical history from Adam to Saul, is notable for listing and naming seven of Magog's sons, and mentions his "thousands" of descendants.[32] The Samaritan Torah and the Septuagint (a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible made during the last few centuries of the pre-Christian era) occasionally introduce the name of Gog where the Hebrew original has something else, or use Magog where the Hebrew has Gog, indicating that the names were interchangeable.[33]

Chapters 19:11–21:8 of the Book of Revelation, dating from the end of the 1st century AD,[34] tells how Satan is to be imprisoned for a thousand years, and how, on his release, he will rally "the nations in the four corners of the Earth, Gog and Magog," to a final battle with Christ and his saints:[2]

"When the thousand years are over, Satan will be released from his prison and will go out to deceive the nations in the four corners of the Earth—Gog and Magog—and to gather them for battle. In number they are like the sand on the seashore."[35]

Midrashic writings

After the failure of the anti-Roman Bar Kokhba revolt in the 2nd century AD which looked to a human leader as the promised messiah, Jews began to conceive of the messianic age in supernatural terms: first would come a forerunner, the Messiah ben Joseph, who would defeat Israel's enemies, identified as Gog and Magog, to prepare the way for the Messiah ben David;[h] then the dead would rise, divine judgement would be handed out, and the righteous would be rewarded.[37][38]

The aggadah, homiletic and non-legalistic exegetical texts in the classical rabbinic literature of Judaism, treat Gog and Magog as two names for the same nation who will come against Israel in the final war.[39] The rabbis associated no specific nation or territory with them beyond a location to the north of Israel,[40] but the great Jewish scholar Rashi identified the Christians as their allies and said God would thwart their plan to kill all Israel.[41]

Alexander the Great

The 1st century Jewish historian Josephus identified the Gog and Magog people as Scythians, horse-riding barbarians from around the Don and the Sea of Azov. Josephus recounts the tradition that Gog and Magog were locked up by Alexander the Great behind iron gates in the "Caspian Mountains", generally identified with the Caucasus Mountains. This legend must have been current in contemporary Jewish circles by this period, coinciding with the beginning of the Christian Era.[i][45] Several centuries later, this material was vastly elaborated in the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius and Alexander Romance.[46]

Precursor texts in Syriac

The Pseudo-Methodius, written originally in Syriac, is considered the source of Gog and Magog tale incorporated into Western versions of the Alexander Romance.[47][48] An earlier-dated Syriac Alexander Legend contains a somewhat different treatment of the Gog and Magog material, which passed into the lost Arabic version,[49] or the Ethiopic and later Oriental versions of the Alexander romance.[50][j]

In the Syriac Alexander Legend dating to 629–630, Gog (Template:Lang-syr, gwg) and Magog (Template:Lang-syrܵ, mgwg) appear as kings of Hunnish nations.[k][51] Written by a Christian based in Mesopotamia, the Legend is considered the first work to connect the Gates with the idea that Gog and Magog are destined to play a role in the apocalypse.[52] The legend claims that Alexander carved prophecies on the face of the Gate, marking a date for when these Huns, consisting of 24 nations, will breach the Gate and subjugate the greater part of the world.[l][53][54]

The Pseudo-Methodius added a new element into the narrative: two mountains moving together to narrow the corridor, which was then sealed with a gate against Gog and Magog. This idea found its way into both the Western Alexander Romance and the Quran.[55]

Alexander romances

This Gog and Magog legend is not found earlier versions of the Alexander Romance of Pseudo-Callisthenes, whose oldest manuscript dates to the 3rd century,[m] but an interpolation into recensions around the 8th century.[n][57] In the latest and longest Greek version[o] are described the Unclean Nations, which include the Goth and Magoth as their kings, and whose people engage in the habit of eating worms, dogs, human cadaver and fetuses.[58] They were allied to Belsyrians (Bebrykes,[59] of Bythinia in modern-day North Turkey), and sealed beyond the "Breasts of the North", a pair of mountains fifty-days' march away towards the north.[p][58]

Gog and Magog appear in somewhat later Old French versions of the romance.[q][60] In the verse Roman d'Alexandre, Branch III, of Lambert le Tort (c. 1170), Gog and Magog ("Gos et Margos", "Got et Margot") were vassals to Porus, king of India, providing an auxiliary force of 400,000 men.[r] Routed by Alexander, they escaped through a defile in the mountains of Tus (or Turs),[s] and were sealed by the wall erected there, to last until the advent of the Antichrist.[t][61][62] Branch IV of the poetic cycle tells that the task of guarding Gog and Magog, as well as the rule of Syria and Persia was assigned to Antigonus, one of Alexander's successors.[63]

Gog and Magog also appear in Thomas de Kent's Roman de toute chevalerie (c. 1180), where they are portrayed as cave-dwellers who consume human flesh. A condensed account occurs in a derivative work, the Middle English King Alisaunder (vv. 5938–6287).[64][65][66] In the 13th century French Roman d'Alexandre en prose, Alexander has an encounter with cannibals who have taken over the role of Gog and Magog.[67] This is a case of imperfect transmission, since the prose Alexander's source, the Latin work by Archpriest Leo of Naples known as Historia de Preliis, does mention "Gogh et Macgogh", at least in some manuscripts.[68]

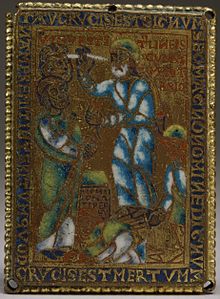

The Gog and Magog are not only human flesh-eaters, but illustrated as men "a notably beaked nose" in examples such as the "Henry of Mainz map", an important example of Mappa mundi.[69] Gog and Magog caricaturized as figures with hooked noses on a miniature depitcting their attack of the Holy City, found in a manuscript of the Apocalypse in Anglo-Norman.[u][26]

Identification with civilizations

Early Christian writers (e.g. Eusebius) frequently identified Gog and Magog with the Romans and their emperor.[70] After the Empire became Christian, Ambrose (d.397) identified Gog with the Goths, Jerome (d. 420) with the Scythians and Jordanes (died c. 555) said that Goths, Scythians and Amazons were all the same; he also cited Alexander's gates in the Caucasus.[71][v] The Byzantine writer Procopius said it was the Huns Alexander had locked out, and a Western monk named Fredegar seems to have Gog and Magog in mind in his description of savage hordes from beyond Alexander's gates who had assisted the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (610–641) against the Saracens.[73]

Nomadic identification

As one nomadic people followed another on the Eurasian steppes, so the identification of Gog and Magog shifted. In the 9th and 10th centuries these kingdoms were identified by some with the lands of the Khazars, a Turkic people who had converted to Judaism and whose empire dominated Central Asia–the 9th-century monk Christian of Stavelot referred to Gazari, said of the Khazars that they were "living in the lands of Gog and Magog" and noted that they were "circumcised and observing all [the laws of] Judaism".[74][75] Arab traveler ibn Fadlan also reported of this belief, writing around 921 he recorded that "Some hold the opinion that Gog and Magog are the Khazars".[76]

After the Khazars came the Mongols, seen as a mysterious and invincible horde from the east who destroyed Muslim empires and kingdoms in the early 13th century; kings and popes took them for the legendary Prester John, marching to save Christians from the Saracens, but when they entered Poland and Hungary and annihilated Christian armies a terrified Europe concluded that they were "Magogoli", the offspring of Gog and Magog, released from the prison Alexander had constructed for them and heralding Armageddon.[77]

Europeans in Medieval China reported findings from their travels to the Mongol Empire. Some accounts and maps began to place the "Caspian Mountains", and Gog and Magog, just outside the Great Wall of China. The Tartar Relation, an obscure account of Friar Carpini's 1240s journey to Mongolia, is unique in alleging that these Caspian Mountains in Mongolia, "where the Jews called Gog and Magog by their fellow countrymen are said to have been shut in by Alexander", were moreover purported by the Tartars to be magnetic, causing all iron equipment and weapons to fly off toward the mountains on approach.[78] In 1251, the French friar André de Longjumeau informed his king that the Mongols originated from a desert further east, and an apocalyptic Gog and Magog ("Got and Margoth") people dwelled further beyond, confined by the mountains.[79]

In fact, Gog and Magog were held by the Mongol to be their ancestors, at least by some segment of the population. As traveler and Friar Riccoldo da Monte di Croce put it in c. 1291, "They say themselves that they are descended from Gog and Magog: and on this account they are called Mogoli, as if from a corruption of Magogoli".[80][81][82] Marco Polo, traveling when the initial terror had subsided, places Gog and Magog among the Tartars in Tenduc, but then claims that the names Gog and Magog are translations of the place-names Ung and Mungul, inhabited by the Ung and Mongols respectively.[83][84]

An explanation offered by Orientalist Henry Yule was that Marco Polo was only referring to the "Rampart of Gog and Magog", a name for the Great Wall of China.[85] Friar André's placement of Gog and Magog far east of Mongolia has been similarly explained.[79]

The confined Jews

Some time around the 12th century, the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel came to be identified with Gog and Magog;[86] possibly the first to do so was Petrus Comestor in Historica Scholastica (c. 1169–1173),[87][88] and he was indeed a far greater influence than others before him, although the idea had been anticipated by the aforementioned Christian of Stavelot, who noted that the Khazhars, to be identified with Gog and Magog, was one of seven tribes of the Hungarians and had converted to Judaism.[74][75]

While the confounding Gog and Magog as confined Jews was becoming commonplace, some, like Riccoldo or Vincent de Beauvais remained skeptics, and distinguished the Lost Tribes from Gog and Magog.[80][89][90] As noted, Riccoldo had reported a Mongol folk-tradition that they were descended Gog and Magog. He also addressed many minds (Westerners or otherwise[91]) being credulous of the notion that Mongols might be Captive Jews, but after weighing the pros and cons, he concluded this was an open question.[w][82][92]

The Flemish Franciscan monk William of Rubruck, who was first-hand witness to Alexander's wall in Derbent on the shores of the Caspian Sea in 1254,[x] identified the people the walls were meant to fend off only vaguely as "wild tribes" or "desert nomads",[y][95] but one researcher made the inference Rubruck must have meant Jews,[z] and that he was speaking in the context of "Gog and Magog".[aa][91] Confined Jews were later to be referred to as "Red Jews" (die roten juden) in German-speaking areas; a term first used in a Holy Grail epic dating to the 1270s, in which Gog and Magog were two mountains enclosing these people.[ab][96]

The author of the Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a 14th-century best-seller, said he had found these Jews in Central Asia where as Gog and Magog they had been imprisoned by Alexander, plotting to escape and join with the Jews of Europe to destroy Christians.[97]

Gog and Magog in Muslim tradition

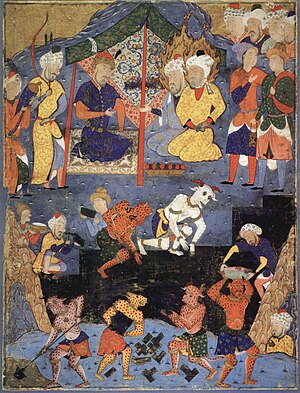

The conflation of Gog and Magog with the legend of Alexander and the Iron Gates was disseminated throughout the Near East in the early centuries of the Christian era.[100] In the Qu'ran Surah 18, Yajuj and Majuj (Gog and Magog) are suppressed by Dhul-Qarnayn "the two-horned one", commonly interpreted to mean Iskandar (Alexander the Great).[101] Dhul-Qarnayn, having journeyed to the ends of the world, meets "a people who scarcely understood a word" who seek his help in building a barrier that will separate them from the people of Yajuj and Majuj who "do great mischief on earth". He agrees to build it for them, but warns that when the time comes (Last Age), Allah will remove the barrier and Yajuj and Majuj will swarm through.[102]

The early Muslim traditions were summarised by Zakariya al-Qazwini (d. 1283) in two popular works called the Cosmography and the Geography. Gog and Magog, he says, live near to the sea that encircles the Earth and can be counted only by God; they are only half the height of a normal man, with claws instead of nails and a hairy tail and huge hairy ears which they use as mattress and cover for sleeping.[103] They scratch at their wall each day until they almost break through, and each night God restores it, but when they do break through they will be so numerous that "their vanguard is in Syria and their rear in Khorasan".[104]

When Yajuj and Majuj were identified with real peoples it was the Turks, who threatened Baghdad and northern Iran;[105] later, when the Mongols destroyed Baghdad in 1258, it was they who were Gog and Magog.[106] The wall dividing them from civilised peoples was normally placed towards Armenia and Azerbaijan, but in the year 842 the Caliph Al-Wathiq had a dream in which he saw that it had been breached, and sent an official named Sallam to investigate.[107] Sallam returned a little over two years later and reported that he had seen the wall and also the tower where Dhul Qarnayn had left his building equipment, and all was still intact.[108] It is not entirely clear what Sallam saw, but he may have reached the Jade Gate, the westernmost customs point on the border of China.[109] Somewhat later the 14th-century traveller Ibn Battuta reported that the wall was sixty days' travel from the city of Zeitun, which is on the coast of China; the translator notes that Ibn Battuta has confused the Great Wall of China with that built by Dhul-Qarnayn.[110]

Modern apocalypticism

In the early 19th century, some Chasidic rabbis identified Napoleon's invasion of Russia as "The War of Gog and Magog".[111] But as the century progressed, apocalyptic expectations receded as the populace in Europe began to adopt an increasingly secular worldview.[112] This has not been the case in the United States, where a 2002 poll indicated that 59% of Americans believed the events predicted in the Book of Revelation would come to pass.[113] During the Cold War the idea that Russia had the role of Gog gained popularity, since Ezekiel's words describing him as "prince of Meshek"—rosh meshek in Hebrew—sounded suspiciously like Russia and Moscow.[15] Even some Russians took up the idea, apparently unconcerned by the implications ("Ancestors were found in the Bible, and that was enough"), as did Ronald Reagan.[114][115]

Post Cold War-millenarians still identify Gog with Russia, but they now tend to stress its allies among Islamic nations, especially Iran.[116] For the most fervent, the countdown to Armageddon began with the return of the Jews to Israel, followed quickly by further signs pointing to the nearness of the final battle–nuclear weapons, European integration, Israel's seizure of Jerusalem, and America's wars in Afghanistan and the Gulf.[117] In the prelude to the 2003 Invasion of Iraq, President George W. Bush told Jacques Chirac, "Gog and Magog are at work in the Middle East". "This confrontation", he urged the French leader, "is willed by God, who wants to use this conflict to erase His people's enemies before a new age begins".[118] Chirac consulted a professor at the Faculty of Theology of the University of Lausanne to explain Bush's reference.[119]

In the Islamic apocalyptic tradition the end of the world would be preceded by the release of Gog and Magog, whose destruction by God in a single night would usher in the Day of Resurrection.[120] Reinterpretation did not generally continue after Classical times, but the needs of the modern world have produced a new body of apocalyptic literature in which Gog and Magog are identified as the Jews and Israel, or the Ten Lost Tribes, or sometimes as Communist Russia and China.[121] One problem these writers have had to confront is the barrier holding Gog and Magog back, which is not to be found in the modern world: the answer varies, some writers saying that Gog and Magog were the Mongols and that the wall is now gone, others that both the wall and Gog and Magog are invisible.[122]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ All Reubenites are held to be descendants of Reuben in the view of the Torah. But it is unclear what family relationship Gog's father Joel has with the sons of Reuben in verse 3.[3]

- ^ 4Q523 scroll

- ^ The encryption technique is called atbash. BBL ("Babylon") when read backwards and displaced by one letter becomes MGG (Magog).

- ^ The giant mentioned by Geoffrey of Monmouth in Historia Regum Britanniae (1136 AD).

- ^ A Gog is mentioned in I Chronicles 5:4, but he is Gog of the tribe of Reuben, an Israelite, and can hardly be the same as the Gog of Ezekiel.[13]

- ^ Composed between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC

- ^ Tooman's view is that the "latter days" means "the end of history-as we-know-it and the initiation of a new historical age".

- ^ The coming of the Messiah ben David "is contemporary with or just after that of Messiah ben Joseph" (van der Woude (1974), p. 527).[36]

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 1

.123 and 18 .97; The Jewish War 7 .244–51 - ^ The Ethiopic version derives from the lost Arabic version (Boyle 1979, p. 133). While Budge 1889 does not appear to comment, cf. Budge (1896), The Life and Exploits of Alexander, p. 216, fn 1.

- ^ Also called Christian Legend concerning Alexander, ed. tr. by E. A. Wallis Budge. It has a long full-title, which in shorthand reads "An exploit of Alexander.. how.. he made a gate of iron, and shut it [against] the Huns".

- ^ The first invasion, prophesied to occur 826 years after Alexander predicted, has been worked out to fall on 1 October 514; the second invasion on A.D. 629 (Boyle 1979, p. 124).

- ^ The oldest manuscript is recension α. The material is not found in the oldest Greek, Latin, Armenian, and Syriac versions.[56]

- ^ Recension ε

- ^ Recension γ

- ^ Alexander's prayer caused the mountains to move nearer, making the pass narrower, facilitating his building his gate. This is the aforementioned element first seen in pseudo-Methodius.

- ^ Gog and Magog being absent in the Alexandreis (1080) of Walter of Châtillon.

- ^ Note the change in loyalties. According to the Greek version, Gog and Magog served the Belsyrians, whom Alexander fought them after completing his campaign against Porus.

- ^ "Tus" in Iran, near the Caspian south shore, known as Susia to the Greeks, is a city in the itinerary of the historical Alexander. Meyer does not make this identification, and suspects a corruption of mons Caspius etc.

- ^ Branch III, laisses 124–128.

- ^ Toulouse manuscript 815, folio 49v.

- ^ The idea that Gog and Magog were connected with the Goths was longstanding; in the mid-16th century, Archbishop of Uppsala Johannes Magnus traced the royal family of Sweden back to Magog son of Japheth, via Suenno, progenitor of the Swedes, and Gog, ancestor of the Goths).[72]

- ^ Riccoldo observed that the Mongol script resembled Chaldean (Syriac,[92] a form of Aramaic), and in fact it does derive from Aramaic.[93] However he saw that Mongols bore no physical resemblance to Jews and were ignorant of Jewish laws.

- ^ Rubruck refers Derbent as the "Iron Gate", this also being the meaning of the Turkish name (Demir kapi) for the town.[94] Rubruck may have been the only Medieval Westerner to claim to have seen it.[91]

- ^ Also "barbarous nations", "savage tribes".

- ^ Based on Rubruck stating elsewhere "There are other enclosures in which there are Jews"

- ^ Since Roger Bacon, having been informed by Rubruck, urged the study of geography to discover where the Antichrist and Gog and Magog might be found.

- ^ Albrecht von Scharfenberg, Der jüngere Titurel. It belongs in the Arthurian cycle.

References

Citations

- ^ Bøe 2001, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Mounce, Robert H (1998). The Book of Revelation. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825377.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bøe 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Bøe 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Buitenwerf 2007, p. 166.

- ^ Buitenwerf 2007, p. 172.

- ^ Lust 1999b, pp. 373–374.

- ^ Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch. Bloomsbury. p. 148. ISBN 9780567134394.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lust 1999a, p. 536.

- ^ Bøe 2001, pp. 84, fn 31. Lust and Bøe cite Brownlee (1983) "Son of Man Set Your Face: Ezekiel the Refugee Prophet", HUCA 54.

- ^ Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Stephen (2000), Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford University Press, Gogmagog (or Gog and Magog), ISBN 9780192100191

- ^ Fairholt, Frederick William (1859), Gog and Magog: The Giants in Guildhall; Their Real and Legendary History, John Camden Hotten, pp. 8–11, 130

- ^ Tooman 2011, p. 140.

- ^ Block 1998, p. 432.

- ^ a b Blenkinsopp 1996, p. 178.

- ^ Bullock, C. Hassell (1986). An Introduction to the Old Testament Prophetic Books. Moody Press. p. 301. ISBN 9781575674360.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Tooman 2011, p. 271.

- ^ Ezekiel 38 (NRSV)

- ^ Bøe 2001, pp. 101–104.

- ^ Block 1998, pp. 72–73, 439–440.

- ^ Hays, J. Daniel; Duvall, J. Scott; Pate, C. Marvin (2009). Dictionary of Biblical Prophecy and End Times. Zondervan. p. no pagination. ISBN 9780310571049.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Block 1998, p. 436.

- ^ Tooman 2011, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Tooman 2011, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Petersen, David L. (2002). The prophetic literature: an introduction. John Knox Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780664254537.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Meyer, Paul (1896), "Version anglo-normande en vers de l'Apocalypse", Romania, 25: 176 (plate), and 246, p. 257 note 2

- ^ Boring, Eugene M (1989). Revelation. Westminster John Knox. p. 209. ISBN 9780664237752.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Wardle, Timothy (2010). The Jerusalem Temple and Early Christian Identity. Mohr Siebeck. p. 89. ISBN 9783161505683.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bøe 2001, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Bøe 2001, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Bøe 2001, p. 153.

- ^ Bøe 2001, pp. 186–189.

- ^ Lust 1999a, pp. 536–537.

- ^ Stuckenbruck, Loren T. (2003). "Revelation". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. pp. 1535–36. ISBN 9780802837110.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Revelation 20:7–10

- ^ Bøe 2001, p. 201.

- ^ Schreiber, Mordecai; Schiff, Alvin I.; Klenicki, Leon (2003). "Messianism". In Schreiber, Mordecai; Schiff, Alvin I.; Klenicki, Leon (eds.). The Shengold Jewish Encyclopedia. Rockville, Maryland: Schreiber Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 9781887563772.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bøe 2001, pp. 201–204.

- ^ Skolnik & Berenbaum 2007, p. 684.

- ^ Mikraot Gedolot HaMeor p. 400

- ^ Grossman, Avraham (2012). "The Commentary of Rashi on Isaiah and the Jewish-Christian Debate". In Wolfson, Elliot R.; Schiffman, Lawrence H.; Engel, David (eds.). Studies in Medieval Jewish Intellectual and Social History. Brill. p. 54. ISBN 9789004222366.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Westrem 1998, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Massing 1991, pp. 31, 32 n60.

- ^ Siebold, Jim (2015). "The Catalan Atlas (#235)". My Old Maps. Retrieved 2016-08-12.

- ^ Bietenholz 1994, p. 122.

- ^ Bietenholz 1994, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Stoneman 1991, p. 29.

- ^ Boyle 1979, p. 123.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 32.

- ^ Budge 1889, II, p. 150.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Budge 1889, II, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. 17–21.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. 17, 21.

- ^ Stoneman 1991, pp. 28–32.

- ^ a b Stoneman 1991, pp. 185–187.

- ^ Anderson 1932, p. 35.

- ^ Westrem 1998, p. 57.

- ^ Armstrong 1937, VI, p. 41.

- ^ Meyer 1886, summary of §11 (Michel ed., pp. 295–313), pp. 169–170; appendix II on Gog and Magog episode, pp. 386–389; on third branch, pp. 213, 214.

- ^ Meyer 1886, p. 207.

- ^ Anderson 1932, p. 88.

- ^ Harf-Lancner, Laurence (2012), Maddox, Donald; Sturm-Maddox, Sara (eds.), "From Alexander to Marco Polo, from Text to Image: The Marvels of India", Medieval French Alexander, SUNY Press, p. 238, ISBN 9780791488324

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Akbari, Suzanne Conklin (2012), Idols in the East: European Representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100–1450, Cornell University Press, p. 104, ISBN 9780801464973

- ^ Warren, Michelle R. (2012), Maddox, Donald; Sturm-Maddox, Sara (eds.), "Take the World by Prose: Modes of Possession in the Roman d'Alexandre", Medieval French Alexander, SUNY Press, pp. 149, fn 17, ISBN 9780791488324

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Michael 1982, p. 133.

- ^ Westrem (1998), p. 61.

- ^ Lust 1999b, p. 375.

- ^ Bietenholz 1994, p. 125.

- ^

Derry, T.K (1979). A History of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland. University of Minnesota Press. p. 129 (fn). ISBN 9780816637997.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bietenholz 1994, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Brook 2006, pp. 7–8, 96.

- ^ a b Westrem 1998, p. 65.

- ^ Brook 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Marshall 1993, pp. 12, 120–122, 144.

- ^ Painter, George D. Painter, ed. (1965), The Tartar Relation, Yale University, pp. 64–65

- ^ a b William of Rubruck & Rockhill (tr.) 1900, pp. xxi, fn 2.

- ^ a b Boyle 1979, p. 126.

- ^ Marco Polo & Yule (tr.) 1875, pp. 285, fn 5.

- ^ a b Westrem 1998, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Marco Polo & Yule (tr.) 1875, pp. 276–286.

- ^ Strickland, Deborah Higgs (2008). "Text, Image and Contradiction in the Devisement du monde". In Akbari, Suzanne Conklin; Iannucci, Amilcare (eds.). Marco Polo and the Encounter of East and West. University of Toronto Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780802099280.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Marco Polo & Yule (tr.) 1875, pp. 283, fn 5.

- ^ Gow 1995, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Gow 1995, p. 42.

- ^ Boyle 1979, p. 124.

- ^ Bietenholz 1994, p. 134.

- ^ Gow 1995, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c Westrem 1998, p. 66.

- ^ a b Marco Polo & Yule (tr.) 1875, pp. 58, fn 3.

- ^ Boyle 1979, p. 125, note 19.

- ^ William of Rubruck & Rockhill (tr.) 1900, pp. xlvi, 262 note 1.

- ^ William of Rubruck & Rockhill (tr.) 1900, pp. xlvi, 100, 120, 122, 130, 262–263 and fn.

- ^ Gow 1995, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Westrem 1998, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Chester Beatty Library. "Iskandar Oversees the Building of the Wall". image gallery. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ Amín, Haila Manteghí (2014). La Leyenda de Alejandro segn el Šāhnāme de Ferdowsī. La transmisión desde la versión griega hast ala versión persa (PDF) (Ph. D). p. 196 and Images 14, 15: Universidad de Alicante.

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Bietenholz 1994, p. 123.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. 57, fn 3.

- ^

Hughes, Patrick Thomas (1895) [1885]. Dictionary of Islam. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120606722.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. 65–68.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Filiu 2011, p. 30.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. xvii–xviii, 82.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. xvii–xviii, 244.

- ^ Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, pp. xvii–xviii.

- ^ Gibb, H.A.R.; Beckingham, C.F. (1994). The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Vol. IV). Hakluyt Society. pp. 896, fn 30. ISBN 9780904180374.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Wessels 2013, p. 205.

- ^ Kyle 2012, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Filiu 2011, p. 196.

- ^ Boyer, Paul (1992). When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern Culture. Belknap Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780674028616.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Marsh, Christopher (2011). Religion and the State in Russia and China. A&C Black. p. 254. ISBN 9781441112477.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Kyle 2012, p. 171.

- ^ Kyle 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Smith, Jean Edward (2016). Dictionary of Biblical Prophecy and End Times. Simon and Schuster. p. 339. ISBN 9781476741192.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Wessels 2013, pp. 193, fn 6.

- ^ Cook 2005, pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Cook 2005, pp. 12, 47, 206.

- ^ Cook 2005, pp. 205–206.

Bibliography

- Monographs

- Anderson, Andrew Runni (1932). Alexander's Gate, Gog and Magog: And the Inclosed Nations. Mediaeval Academy of America.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bøe, Sverre (2001). Gog and Magog: Ezekiel 38–39 as Pre-text for Revelation 19,17–21 and 20,7–10. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161475207.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Buitenwerf, Rieuwerd (2007). "The Gog and Magog Tradition in Revelation 20:8". In de Jonge, H. J.; Tromp, Johannes (eds.). The Book of Ezekiel and its Influence. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754655831.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Michael, Ian (1982), "Typological Problems in Medieval Alexander Literature: The Enclosure of Gog and Magog", The Medieval Alexander Legend and Romance Epic: Essays in Honour of David J.A. Ross, New York: Kraus International Publication, pp. 131–147, ISBN 9780527626006

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tooman, William A. (2011). Gog of Magog: Reuse of Scripture and Compositional Technique in Ezekiel 38–39. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161508578.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van Donzel, Emeri J.; Schmidt, Andrea Barbara (2010). Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources: Sallam's Quest for Alexander's Wall. Brill. ISBN 9004174168.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Westrem, Scott D. (1998). Tomasch, Sylvia; Sealy, Gilles (eds.). "Against Gog and Magog". University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216350.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Encyclopedias

- Lust, J. (1999a). Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter (eds.). Magog. Brill. ISBN 9780802824912.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lust, J. (1999b), Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter (eds.), "Gog", Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible, Brill, ISBN 9780802824912

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael (2007). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 7. Granite Hill Publishers. p. 684. ISBN 9780028659350.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Biblical studies

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1996). A History of Prophecy in Israel (revised and enlarged ed.). Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664256395.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Block, Daniel I. (1998). The Book of Ezekiel: Chapters 25-48. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825360.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Literary

- Armstrong, Edward C. (1937). The Medieval French Roman d'Alexandre. Vol. VI. Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bietenholz, Peter G. (1994). Historia and Fabula: Myths and Legends in Historical Thought from Antiquity to the Modern Age. Brill. ISBN 9004100636.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boyle, John Andrew (1979), "Alexander and the Mongols", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (2): 123–136 JSTOR 25211053

- Budge, Sir Ernest Alfred Wallis, ed. (1889). "A Christian Legend concerning Alexander". The History of Alexander the Great, Being the Syriac Version. Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–158.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meyer, Paul (1886). Alexandre le Grand dans la littérature française du moyen âge. F. Vieweg.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stoneman, Richard (tr.), ed. (1991). The Greek Alexander Romance. Penguin. ISBN 9780141907116.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Geography and ethnography

- Brook, Kevin A (2006). The Jews of Khazaria. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442203020.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gow, Andrew Colin (1995). The Red Jews: Antisemitism in an Apocalyptic Age, 1200–1600. Brill. ISBN 9004102558.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marshall, Robert (1993). Storm from the East: from Genghis Khan to Khubilai Khan. University of California Press. pp. 6–12, 120–122, 144. ISBN 9780520083004.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Massing, Michel (1991), Levenson, Jay A. (ed.), "Observations and Beliefs: The World of the Catalan Atlas", Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration, Yale University Press, pp. 31, 32 n60, ISBN 0300051670

- Polo, Marco (1875), "Ch. 59: Concerning the Province of Tenduc, and the Descendants of Prester John", in Yule, Henry (tr.) (ed.), The Book of Sir Marco Polo, the Venetian, vol. 1 (2nd, revised ed.), J. Murray, pp. 276–286 (

The full text of Chapter 59 at Wikisource)

The full text of Chapter 59 at Wikisource) - William of Rubruck (1900). Rockhill, William Woodville (ed.). The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World, 1253–55. Hakluyt Society. pp. xlvi, 100, 120, 122, 130, 262–263 and fn.

- Modern apocalyptic thought

- Cook, David (2005). Contemporary Muslim Apocalyptic Literature. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630586.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Filiu, Jean-Pierre (2011). Apocalypse in Islam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520264311.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kyle, Richard G. (2012). Apocalyptic Fever: End-Time Prophecies in Modern America. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781621894100.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wessels, Anton (2013). The Torah, the Gospel, and the Qur'an: Three Books, Two Cities, One Tale. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802869081.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)