Jewish exodus from the Muslim world

| Part of a series on |

| Aliyah |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

| Pre-Modern Aliyah |

| Aliyah in modern times |

| Absorption |

| Organizations |

| Related topics |

The Jewish exodus from Arab lands refers to the 20th century expulsion or mass departure of Jews, primarily of Sephardi and Mizrahi background, from Arab and Islamic countries. The migration started in the late 19th century, but accelerated after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. According to official Arab statistics, 856,000 Jews left their homes in Arab countries from 1948 until the early 1970s. Some 680,000 resettled in Israel. Their descendants, and those of Iranian and Turkish Jews, now number 3.06 million of Israel's 5.4 to 5.8 million Jewish citizens. [1] They left behind property valued today at more than $300 billion.[2][3] Jewish-owned real-estate left behind in Arab lands has been estimated at 100,000 square kilometers (four times the size of the State of Israel). [1][3]

Reasons for emigration

While violence and discrimination against Jews in Arab countries started to increase before 1948, it escalated significantly starting in 1948 despite the fact that Jews were indigenous and for the most part held Arab citizenship. Sometimes the process was state sanctioned; at other times it was the consequence of anti-Jewish resentment by non-Jews. Harassment, persecution and the confiscation of property followed. Secondly and in response to mistreatment of Jews in these countries, a Zionist drive for Jewish immigration from Arab lands to Israel intensified. The great majority of Jews in Arab lands eventually emigrated to the modern State of Israel.[4]

The process grew apace as Arab nations under French, British and Italian colonial rule or protection gained independence. Further, anti-Jewish sentiment within the Arab-majority states was exacerbated by the Arab-Israeli wars. Within a few years after the Six Day War (1967) there were only remnants of Jewish communities left in most Arab lands. Jews in Arab lands were reduced from more than 800,000 in 1948 to perhaps 16,000 in 1991.[4]

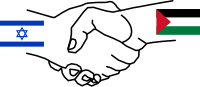

Some claim that the Jewish exodus from Arab lands is a historical parallel to the Palestinian exodus during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, while others reject this comparison as simplistic.[5] One Palestinian sociologist has commented that the loss of Jewish property in Arab lands fulfills the conditions of a sulha, or reconciliation, since Jews as well as Palestinians have experienced a catastrophe, and that publicizing this knowledge would pave the way to a true peace process.[1]

History of Jews in Arab lands (Pre-1948)

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Jewish settlement all over the Fertile Crescent, which is now divided into several Arab states, is well attested since the Babylonian captivity. After the conquest of these lands by Arab Muslims in the 7th century, Jews, along with Christians and Zoroastrians, were accorded the legal status of dhimmi. As such, they were entitled to limited rights, tolerance, and protection, on the condition they pay a special poll tax (the 'jizya'). In return for the tax, dhimmis were exempted from military service. Dhimmi status brought with its several restrictions, the application and severity of which varied by time and place: residency in segregated quarters, obligation to wear distinctive clothing, public subservience to Muslims, prohibitions against proselytizing and marrying Muslim women (according to Islam, a Muslim woman can only marry a Muslim man), and limited access to the legal systems. Notwithstanding these provisions, Jews could at times attain high positions in government, notably as viziers and physicians. Jewish communities, like Christian ones, were typically constituted as semi-autonomous entities managed by their own laws and leadership, who bore responsibility for the community towards the Muslim rulers. Taxes and fines levied on them were collective in nature. However, a level of political autonomy and civil courts for resolving community disputes was not rare.

Mass murders of Jews and deaths due to political instability did however occur in North Africa throughout the centuries and especially in Morocco, Libya and Algeria where eventually Jews were forced to live in ghettos.[6] Decrees ordering the destruction of synagogues were enacted at various times in the Middle Ages in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Instances exist of Jews being forced to convert to Islam or face death in Yemen, Morocco and Baghdad.[7]

This situation, wherein Jews both enjoyed cultural and economical prosperity at times, but were then widely persecuted at other times was summarised by G.E. von Grunebaum as follows:

It would not be difficult to put together the names of a very sizeable number of Jewish subjects or citizens of the Islamic area who have attained to high rank, to power, to great financial influence, to significant and recognized intellectual attainment; and the same could be done for Christians. But it would again not be difficult to compile a lengthy list of persecutions, arbitrary confiscations, attempted forced conversions, or pogroms.[8]

In 1945, there were between 758,000 and 866,000 Jews (see table below) living in communities throughout the Arab world. Today, there are fewer than 7,000. In some Arab states, such as Libya (which was once around 3% Jewish), the Jewish community no longer exists; in other Arab countries, only a few hundred Jews remain.

| Country or territory | 1948 Jewish population |

Jewish % of total population, 1948 |

Estimated Jewish population 2001[9] |

Estimated Jewish population 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aden | 8,000[10] | ~0 | ||

| Algeria | 140,000[10][11] | 1.6% | ~0 | |

| Bahrain | 550-600[12] | 0.5% | 36 | around 30 people. See [13]. |

| Egypt | 75,000[10]-80,000[11] | 0.4% | ~100 | Less than a hundred remain. See[14] |

| Iraq | 135,000[10]-140,000[11] | 2.6% | ~200 | 20 in Baghdad and fewer than 100 remain. See [15]. |

| Lebanon | 5,000[10]-20,000[16] | 0.4-1.5% | < 100 | around 40 in Beirut. See [17] |

| Libya | 35,000[11]-38,000[10] | 3.6% | 0 | |

| Morocco | 250,000[11]-265,000[10] | 2.8% | 5,230 | less than 7,000. See [18] |

| Qatar | ? | ? | ? | a few Jews are reported. See [19] |

| Syria | 15,000[11]-30,000[10] | 0.4-0.9% | ~100 | fewer than 30 remain. See [20] |

| Tunisia | 50,000[11]-105,000[10] | 1.4-3.0% | ~1,000 | in 2004 estimated 1,500 remain. See [21] |

| Yemen | 45,000[11]-55,000[10] | 1.0% | ~200 | a few hundred remain. See [22] |

| Total | 758,000 - 881,000 | <6,500 | <8,600+ |

| Country or territory | 1948 Jewish population |

Estimated Jewish population 2001 |

Estimated Jewish population 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 5,000 | 1[23] | |

| Iran | 70,000-120,000,[24] 100,000, 140,000–150,000 | 11,000-40,000 | less than 40,000 remain. See [25]. |

| Pakistan | 2,000 | N/A | |

| Turkey | 80,000[26] | 18,000-30,000[27] |

Jews flee Arab states (1948-)

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the exodus of approximately 711,000 (UN estimate) Arab refugees (see the Palestinian Exodus), the creation of the state of Israel, and the independence of Arab countries from European control, conditions for Jews in the Arab world deteriorated. Over the next few decades, most would leave the Arab world. Their departure and its motivations are covered country by country below.

Soon after the declaration of the establishment of Israel in 1948, over 45,000 Jews had emigrated from Arab countries to mandatory Palestine. Although some of the Jews emigrated because of the influence of Zionism that proclaimed the right of the Jewish people to return to their homeland, most Jews came to Israel as a result of persecution by Arab countries. Gilbert (1999) maintains that Israeli officials were instrumental in facilitating population transfers from Muslim countries, known in Israel as the gathering of the exiles, because there was a shortage of manpower in Israel after 1948.

There are controversial claims about the methods employed by Israeli officials. Gilbert (1999) and Hirst (1977) write that Israeli agents planted bombs in synagogues and Jewish businesses in an attempt to stimulate emigration to Israel, but that view is rejected by others. Historian Moshe Gat contends that, in the most famous case in Iraq, the claim that the bombings were carried out by Zionists is contrary to the evidence, and in any event the impetus for the Jewish-Iraqi exodus was the imminent expiration of the denaturalisation law, not the bombing.[28] According to Norman Stillman, "[n]either side, however, has provided truly convincing evidence, and for any detached observer the point must remain moot."[29]

The United Nations Resolution on the partition of Palestine in November 1947 and the declaration of the State of Israel in 1948 led to anti-Jewish actions in Arab countries. At the same time, several Arab countries began to take a severe attitude against Jews who operated Zionist activities within Arab borders, further encouraging Jewish emigration to Israel.[30][31] Arab pogroms against Jews appeared to spread throughout the Arab world, and there were intensified riots in Yemen and Syria in particular. In Libya, Jews were deprived citizenship, and in Iraq, their property was seized. As a result, a large number of Jews were forced to emigrate and they were not allowed to take all their property. Between 1948 and 1951, tens of thousands of Jews from Iraq and Yemen arrived in Israel by the airlift operation arranged by the Israeli authorities and local communities.[32].

By 1951, about 30 percent of the population in Israel was accounted for by Jews from Arab countries and about 850,000 Jews emigrated from Arab countries between 1948 and 1952. During this time 586,269 Jews came to Israel from Arab countries, and 3,136,436 people live in Israel today including their offspring, which account for about 41 per cent of the total population.[33]

Algeria

Almost all Jews in Algeria left upon independence in 1962. Algeria's 140,000 Jews had French citizenship since 1870 (briefly revoked by Vichy France in 1940), and they mainly went to France, with some going to Israel.[34]

Following the brutal Algerian Civil War of 1990s there – in particular, the rebel Armed Islamic Group's 1994 declaration of war on all non-Muslims in the country – most of the thousand-odd Jews previously there, living mainly in Algiers and to a lesser extent Blida, Constantine, and Oran, emigrated. The Algiers synagogue was abandoned after 1994. These Jews themselves represented the remainder of only about 10,000 who had chosen to stay there in 1962

Only a small number of Algerian origin Jews moved from France to Israel.

Bahrain

Bahrain's tiny Jewish community, mostly the descendants of immigrants who entered the country in the early 1900s from Iraq, numbered 600 in 1948.

In the wake of the November 29, 1947 U.N. Partition vote, demonstrations against the vote in the Arab world were called for December 2-5. The first two days of demonstrations in Bahrain saw rock throwing against Jews, but on December 5 mobs in the capital of Manama looted Jewish homes and shops, destroyed the synagogue, and beat any Jews they could find, and murdered one elderly woman.[35]

Over the next few decades, most left for other countries, especially England; as of 2006 only 36 remained.[36]

Relations between Jews and Muslims are generally considered good, with Bahrain being the only state on the Arabian Peninsula where there is a specific Jewish community and the only Gulf state with a synagogue. One member of the community, Rouben Rouben, who sells electronics and appliances from his downtown showroom, said “95 percent of my customers are Bahrainis, and the government is our No. 1 corporate customer. I’ve never felt any kind of discrimination.”[36]

Members play a prominent role in civil society: Ebrahim Nono was appointed in 2002 a member of Bahrain's upper house of parliament, the Consultative Council, while a Jewish woman heads a human rights group, the Bahrain Human Rights Watch Society. According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the active Jewish community is "a source of pride for Bahraini officials".[36]

In Bahrain's 2006 parliamentary election, some candidates have specifically sought out the Jewish vote; writer Munira Fakhro, Vice President of the Leftist National Democratic Action, standing in Isa Town told the local press: "There are 20- 30 Jews in my area and I would be working for their benefit and raise their standard of living."[37]

Egypt

Egypt was once home to one of the most dynamic Jewish communities in the Diaspora. Caliphs in the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries CE exercised various repressive policies, culminating in the murder of Jews and the destruction of the Jewish quarter in Cairo in 1012. Jewish life was subject to ups and downs until the rise of the Ottoman Empire in 1517, when it deteriorated again. Six recorded blood libels took place between 1870 and 1892. In 1948, approximately 75,000 Jews lived in Egypt. About 100 remain today, mostly in Cairo. In June 1948, a bomb exploded in Cairo's Karaite quarter, killing 22 Jews. In July 1948, Jewish shops and the Cairo Synagogue was attacked, killing 19 Jews.[1] Hundreds of Jews were arrested and had their property confiscated. The 1954, the Lavon Affair served as a pretext for further persecution of Egyptian Jews. In October 1956, when the Suez Crisis erupted, 1,000 Jews were arrested and 500 Jewish businesses were seized by the government. A statement branding the Jews "enemies of the state" was read out in the mosques of Cairo and Alexandria. Jewish bank accounts were confiscated and many Jews lost their jobs. Lawyers, engineers, doctors and teachers were not allowed to work in their professions. In 1967, Jews were detained and tortured, and Jewish homes were confiscated.[1]

In 1951, the fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion was translated into Arabic and promoted as an authentic historical document, fueling anti-Semitic sentiments in Egypt.[38] In 1960, the Protocols were the subject of an article by Salah Dasuqi, military governor of Cairo, in al-Majallaaa, the official cultural journal.[39] In 1965, the Egyptian government released an English-language pamphlet titled Israel, the Enemy of Africa and distributed it throughout the English-speaking countries of Africa. The pamphlet used the Protocols and The International Jew as its sources and concluded that all the Jews were cheats, thieves, and murderers.[40]

In October 2002, a private Egyptian television company Dream TV produced a 41-part "historical drama" A Knight Without a Horse (Fars Bela Gewad), largely based on the Protocols,[41] which ran on 17 Arabic-language satellite television channels, including government-owned Egypt Television (ETV), for a month, causing concerns in the West.[42] Egypt's Information Minister Safwat El-Sherif announced that the series "contains no antisemitic material".[43]

Iraq

In 1948, there were approximately 150,000 Jews in Iraq. The community was concentrated in Baghdad, was well established and felt no urge to leave. However by 2003, there were only approximately 100 left of this previously thriving community.

In 1941, following Rashid Ali's pro-Axis coup, riots known as the Farhud broke out in Baghdad in which approximately As a result of Farhud, about 180 Jews were killed and about 240 were wounded, 586 Jewish-owned businesses were looted and 99 Jewish houses were destroyed.[44]

Like most Arab League states, Iraq initially forbade the emigration of its Jews after the 1948 war on the grounds that allowing them to go to Israel would strengthen that state. However, intense diplomatic pressure brought about a change of mind. At the same time, increasing government oppression of the Jews fueled by anti-Israeli sentiment, together with public expressions of anti-semitism, created an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty.[citation needed]

In March 1950, Iraq passed a law of one year duration allowing Jews to emigrate on condition of relinquishing their Iraqi citizenship. Iraq apparently believed it would rid itself of those Jews it regarded as the most troublesome, especially the Zionists, but retain the wealthy minority who played an important part in the Iraqi economy. Israel mounted an operation called "Ezra and Nehemiah" to bring as many of the Iraqi Jews as possible to Israel, and sent agents to Iraq to urge the Jews to register for immigration as soon as possible.[citation needed]

The initial rate of registration accelerated after a bomb injured three Jews at a café. Two months before the expiry of the law, by which time about 85,000 Jews had registered, a bomb at the Masuda Shemtov Synagogue killed 3 or 5 Jews and injured many. The law expired in March 1951, but was later extended after the Iraqi government froze and later appropriated the assets of departing Jews (including those already left).In 1951 the Iraqi Government passed legislation that made affiliation with Zionism a felony and ordered, "the expulsion of Jews who refused to sign a statement of anti-Zionism." [45] During the next few months, all but a few thousand of the remaining Jews registered for emigration, spurred on by a sequence of bombings that caused few casualties but had great psychological impact. In total, about 120,000 Jews left Iraq.[citation needed]

In May and June 1951, the arms caches of the Zionist underground in Iraq, which had been supplied from Palestine/Israel since the Farhud of 1942, were discovered. Many Jews were arrested and two Zionist activists, Yusuf Basri and Ibrahim Salih, were tried and hanged for three of the bombings. A secret Israeli inquiry in 1960 reported that most of the witnesses believed that Jews had been responsible for the bombings, but found no evidence that they were ordered by Israel.[46] The issue remains unresolved: some Iraqi activists in Israel still regularly charge that Israel used violence to engineer the exodus, while Israeli officials of the time vehemently deny it. According to historian Moshe Gatt, few historians believe that Israel was actually behind the bombing campaign -- based on factors such as records indicating that Israel did not want such a rapid registration rate and that bomb throwing at Jewish targets was common before 1950, making the Istiqlal Party a more likely culprit than the Zionist underground. In any case, the remainder of Iraq's Jews left over the next few decades. and had mostly gone by 1970. In 1969 eleven Jews were hanged, nine of them on January 27 in the public squares of Baghdad and Basra. The 2,500 remnant of the community almost entirely fled shortly thereafter.[citation needed]

Lebanon

In 1948, there were approximately 5,000 Jews in Lebanon, with communities in Beirut, and in villages near Mount Lebanon, Deir al Qamar, Barouk, and Hasbayah. While the French mandate saw a general improvement in conditions for Jews, the Vichy regime placed restrictions on them. The Jewish community actively supported Lebanese independence after World War II and had mixed attitudes toward Zionism.[citation needed]

Negative attitudes toward Jews increased after 1948, and, by 1967, most Lebanese Jews had emigrated - to the United States, Canada, France, and Israel. The remaining Jewish community was particularly hard hit by the civil wars in Lebanon, and, by 1967, most Jews had emigrated. In 1971, Albert Elia, the 69-year-old Secretary-General of the Lebanese Jewish community was kidnapped in Beirut by Syrian agents and imprisoned under torture in Damascus along with Syrian Jews who had attempted to flee the country. A personal appeal by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, Prince Sadruddin Agha Khan to the late President Hafez al-Assad failed to secure Elia's release. In the 1980s, Hizballah kidnapped several Lebanese Jewish businessmen, and in the 2004 elections, only one Jew voted in the municipal elections. By all accounts, there are fewer than 100 Jews left in Lebanon.[citation needed]

Libya

The area now known as Libya was the home of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, dating back to at least 300 BCE. In 1948, about 38,000 Jews lived there.[10][47]

A series of pogroms started in Tripoli in November 1945; over a period of several days more than 130 Jews (including 36 children) were killed, hundreds were injured, 4,000 were left homeless, and 2,400 were reduced to poverty. Five synagogues in Tripoli and four in provincial towns were destroyed, and over 1,000 Jewish residences and commercial buildings were plundered in Tripoli alone.[48] The pogroms continued in June 1948, when 15 Jews were killed and 280 Jewish homes destroyed.[49]

Between the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and Libyan independence in December 1951 over 30,000 Libyan Jews emigrated to Israel. In 1967, during the Six-Day War, the Jewish population of 4,000 was again subjected to pogroms in which 18 were killed, and many more injured. The Libyan government "urged the Jews to leave the country temporarily", permitting them each to take one suitcase and the equivalent of $50. In June and July over 4,000 traveled to Italy, where they were assisted by the Jewish Agency. 1,300 went on to Israel, 2,200 remained in Italy, and most of the rest went to the United Stated. A few scores remained in Libya.[50][51]

In 1970 the Libyan government issued new laws which confiscated all the assets of Libya's Jews, issuing in their stead 15 year bonds. However, when the bonds matured no compensation was paid. Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi justified this on the grounds that "the alignment of the Jews with Israel, the Arab nations' enemy, has forfeited their right to compensation."[52]

Although the main synagogue in Tripoli was renovated in 1999, it has not reopened for services. The last Jew in Libya, Esmeralda Meghnagi died in February, 2002. Israel is home to about 40,000 Jews of Libyan descent, who maintain unique traditions.[3] [4]

Morocco

Jewish communities, in Islamic times often (though not always[5]) living in ghettos known as mellah, have existed in Morocco for at least 2,000 years. Intermittent large scale massacres (such as that of 6,000 Jews in Fez in 1033, over 100,000 Jews in Fez and Marrakesh in 1146 and again in Marrakesh in 1232)[53] were accompanied by systematic discrimination through the years. During the 13th through the 15th centuries Jews were appointed to a few prominent positions within the government, typically to implement decisions.[citation needed] A number of Jews, fleeing the expulsion from Spain and Portugal, settled in Morocco in the 15th century and afterwards, many moving on to the Ottoman Empire.

The imposition of a French protectorate in 1912 alleviated much of the discrimination. In Morocco the Vichy regime during World War II passed discriminatory laws against Jews; for example, Jews were no longer able to get any form of credit, Jews who had homes or businesses in European neighborhoods were expelled, and quotas were imposed limiting the percentage of Jews allowed to practice professions such as law and medicine to two percent.[54] King Muhammad V expressed his personal distaste for these laws, and assured Moroccan Jewish leaders that he would never lay a hand "upon either their persons or property". While there is no concrete evidence of him actually taking any actions to defend Morocco's Jews, it has been argued that he may have worked behind the scenes on their behalf.[55]

In June 1948, soon after Israel was established and in the midst of the first Arab-Israeli war, riots against Jews broke out in Oujda and Djerada, killing 44 Jews. In 1948-9, 18,000 Jews left the country for Israel. After this, Jewish emigration continued (to Israel and elsewhere), but slowed to a few thousand a year. Through the early fifties, Zionist organizations encouraged emigration, particularly in the poorer south of the country, seeing Moroccan Jews as valuable contributors to the Jewish State:

...These Jews constitute the best and most suitable human element for settlement in Israel's absorption centers. There were many positive aspects which I found among them: first and foremost, they all know (their agricultural) tasks, and their transfer to agricultural work in Israel will not involve physical and mental difficulties. They are satisfied with few (material needs), which will enable them to confront their early economic problems.

— Yehuda Grinker, The Emigration of Atlas Jews to Israel [56]

In 1956, Morocco attained independence. Jews occupied several political positions, including three parliamentary seats and the cabinet position of Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. However, that minister, Leon Benzaquen, did not survive the first cabinet reshuffling, and no Jews was appointed again to a cabinet position.[57] Although the relations with the Jewish community at the highest levels of government were cordial, these attitudes were not shared by the lower ranks of officialsdom, which exhibited attitudes that ranged from traditional contempt to outright hostility".[58] Morocco's increasing identification with the Arab world, and pressure on Jewish educational institutions to arabize and conform culturally added to the fears of Moroccan Jews.[58] Emigration to Israel jumped from 8,171 in 1954 to 24,994 in 1955, increasing further in 1956. Beginning in 1956, emigration to Israel was prohibited until 1961; during that time, however, clandestine emigration continued, and a further 18,000 Jews left Morocco. On January 10, 1961, a boat carrying Jews attempting to flee the country sank off the northern coast of the country; the negative publicity associated with this prompted King Muhammad V to again allow emigration, and over the three following years, more than 70,000 Moroccan Jews left the country.[59] By 1967, only 50,000 Jews remained.[60]

The Six-Day War in 1967 led to increased Arab-Jewish tensions worldwide, including Morocco, and Jewish emigration continued. By the early 1970s the Jewish population was reduced to 25,000; however, most of this wave of emigration went to France, Belgium, Spain, and Canada, rather than Israel.[60]

Despite their current small numbers, Jews continue to play a notable role in Morocco; the king retains a Jewish senior adviser, André Azoulay, and Jewish schools and synagogues receive government subsidies. However, Jewish targets have sometimes been attacked (notably in Al-Qaeda's bombing of a Jewish community center in Casablanca, see Casablanca Attacks), and there is sporadic anti-Semitic rhetoric from radical Islamist groups. The late King Hassan II's invitations for Jews to return have not been taken up by the people who emigrated; in 1948, over 250,000[11]-265,000[10] Jews lived in Morocco. By 2001 an estimated 5,230 remained.[9]

According to Esther Benbassa, the migration of Jews from the Maghreb countries was prompted by uncertainty about the future. [61]

Syria

Rioters in Aleppo in 1947 burned the city's Jewish quarter and killed 75 people.[62] In 1948, there were approximately 30,000 Jews in Syria. The Syrian government placed severe restrictions on the Jewish community, including on emigration. Over the next decades, many Jews managed to escape, and the work of supporters, particularly Judy Feld Carr,[63] in smuggling Jews out of Syria, and bringing their plight to the attention of the world, raised awareness of their situation. Following the Madrid Conference of 1991 the United States put pressure on the Syrian government to ease its restrictions on Jews, and on Passover in 1992, the government of Syria began granting exit visas to Jews on condition that they do not emigrate to Israel. At that time, the country had several thousand Jews; today, under a hundred remain. The rest of the Jewish community have emigrated, mostly to the United States and Israel. There is a large and vibrant Syrian Jewish community in South Brooklyn, New York. In 2004, the Syrian government attempted to establish better relations with the emigrants, and a delegation of a dozen Jews of Syrian origin visited Syria in the spring of that year. [64]

Tunisia

Jews have lived in Tunisia for at least 2300 years. In the 13th century, Jews were expelled from their homes in Kairouan and were ultimately restricted to ghettos, known as hara. Forced to wear distinctive clothing, several Jews earned high positions in the Tunisian government. Several prominent international traders were Tunisian Jews. From 1855 to 1864, Muhammad Bey relaxed dhimmi laws, but reinstated them in the face of anti-Jewish riots that continued at least until 1869.[citation needed]

Tunisia, as the only Middle Eastern country under direct Nazi control during World War II, was also the site of anti-Semitic activities such as prison camps, deportations, and other persecution.[citation needed]

In 1948, approximately 105,000 Jews lived in Tunisia. About 1,500 remain today, mostly in Djerba, Tunis, and Zarzis. Following Tunisia's independence from France in 1956, a number of anti-Jewish policies led to emigration, of which half went to Israel and the other half to France. After attacks in 1967, Jewish emigration both to Israel and France accelerated. There were also attacks in 1982, 1985, and most recently in 2002 when a bomb in Djerba took 21 lives (most of them German tourists) near the local synagogue, in a terrorist attack claimed by Al-Qaeda. (See Ghriba synagogue bombing).

The Tunisian government makes an active effort to protect its Jewish minority now and visibly supports its institutions.[citation needed]

Yemen

If one includes Aden, there were about 63,000 Jews in Yemen in 1948. Today, there are about 200 left. In 1947, riots killed at least 80 Jews in Aden. Increasingly hostile conditions led to the Israeli government's Operation Magic Carpet, the evacuation of 50,000 Jews from Yemen to Israel in 1949 and 1950. Emigration continued until 1962, when the civil war in Yemen broke out. A small community remained unknown until 1976, but it appears that all infrastructure is lost now.[citation needed]

Jews in Yemen were long subject to a number of restrictions, ranging from attire, hairstyle, home ownership, marriage, etc. Under the "Orphan's Decree", many Jewish orphans below puberty were raised as Muslims. This practice began in the late 18th century, was suspended under Ottoman rule, then was revived in 1918. Most cases occurred in the 1920s, but sporadic cases occurred until the 1940s. In later years, the Yemenite government has taken some steps to protect the Jewish community in their country.[citation needed]

Absorbing Jewish refugees

Of the nearly 900,000 Jewish refugees, approximately 680,000 were absorbed by Israel; the remainder went to Europe and the Americas.[65][66]

Hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees were temporarily settled in the numerous tent cities called ma'abarot (transit camps) in Hebrew. The ma'abarot existed until 1963. Their population was gradually absorbed and integrated into the Israeli society, a substantial logistical achievement, without help from the United Nations' various refugee organizations.

The pace and direction of this absorption was directed by three main factors:

The International Community

UN Resolution 194 passed in 1948 resolves that "the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible." The Israeli government's support of the mass immigration and resettlement of Arab Jews allowed it to argue in the international arena that this, provided "natural justice" [67] via a population exchange — Arab immigrants for Palestinian refugees. On April 1, 2008, the U.S. Congress unanimously supported House Resolution 185, calling for the recognition of Jewish, Christian, and other refugees from Arab lands[68]. The resolution continued to say that any agreement reached between Israelis and Palestinians, must include recognition of the Jewish refugees as well. The House also made it clear that the subject should be brought before the U.N. General Assembly again, to have them recognize the plight of the Arabic Jews.

The Economy

Economically, a large influx of Jewish citizens was necessary to provide labour for modern industry to develop and for repopulation of the land to maintain agricultural production. Today, almost half of Israel's Jewish population consists of refugees from Arab and Islamic countries and their offspring.

Jewish refugee advocacy groups

| Part of a series on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict |

| Israeli–Palestinian peace process |

|---|

|

There are a number of advocacy groups acting on behalf of Jewish refugees from Arab countries. Some examples include:

- Justice for Jews from Arab Countries seeks to secure rights and redress for Jews from Arab countries who suffered as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict.[69]

- Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa (JIMENA) publicizes the history and plight of the 900,000 Jews indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa who were forced to leave their homes and abandon their property, who were stripped of their citizenship.[70]

- Historical Society of the Jews from Egypt[71] and International Association of Jews from Egypt[72]

- Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center[73]

- Israelis from Iraq remember Babylon [6]

In March 2008, "[f]or the first time ever, ... a Jewish refugee from an Arab country" appeared before the United Nations Human Rights Council. Regina Bublil-Waldman, a Jewish Libyan refugee and founder of JIMENA, "appeared before the UN Human Rights Council wearing her grandmother's Libyan wedding dress."[74] Justice for Jews from Arab Countries presented a report to the UN Human Rights Council about oppression Jews faced in Arab countries that forced them to find amnesty elsewhere.

See also

- Aliyah

- Arab-Israeli conflict

- Anti-Semitism

- Arab anti-Semitism

- Islam and anti-Semitism

- Jewish history

- Jewish population

- Jewish refugees

- Jews by country

- Jews outside Europe under Nazi occupation

- Maghen Abraham Synagogue

- Jews of the Bilad el-Sudan (West Africa)

- Arab Jews

- Mizrahi Jews

References

- ^ a b c d e Schwartz, Adi. "All I wanted was justice" Haaretz. 10 January 2008.

- ^ Group seeks justice for 'forgotten' Jews - International Herald Tribune

- ^ a b Lefkovits, Etgar. "Expelled Jews hold deeds on Arab lands. Jerusalem Post. 16 November 2007. 18 December 2007.

- ^ a b Stillman, 2003, p. xxi.

- ^ Mendes, Philip. THE FORGOTTEN REFUGEES: the causes of the post-1948 Jewish Exodus from Arab Countries, Presented at the 14 Jewish Studies Conference Melbourne March 2002. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- ^ Maurice Roumani, The Case of the Jews from Arab Countries: A Neglected Issue, 1977, pp. 26-27.

- ^ Bat Ye'or, The Dhimmi, 1985, page 61

- ^ . G.E. Von Grunebaum, 'Eastern Jewry Under Islam,' 1971, page 369.

- ^ a b Shields, Jacqueline. "Jewish Refugees from Arab Countries". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Avneri, 1984, p. 276.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stearns, 2001, p. 966.

- ^ The Virtual Jewish History Tour - Bahrain

- ^ History of the Jews in Bahrain

- ^ History of the Jews in Egypt

- ^ History of the Jews in Iraq

- ^ Jews of Lebanon

- ^ History of the Jews in Lebanon

- ^ History_of_the_Jews_in_Morocco

- ^ History of the Jews in Qatar

- ^ History of the Jews in Syria

- ^ History of the Jews in Tunisia

- ^ Yemenite Jews

- ^ BBC NEWS | World | South Asia | 'Only one Jew' now in Afghanistan

- ^ j. - Iranian Jews in U.S. recall their own difficult exodus as they cling to heritage, building new communities

- ^ History of the Jews in Iran

- ^ http://ajcarchives.org/AJC_DATA/Files/1950_7_WJP.pdf

- ^ The Jewish Community of Turkey

- ^ "Historian Moshe Gat argues that there was little direct connection between the bombings and exodus. He demonstrates that the frantic and massive Jewish registration for denaturalisation and departure was driven by knowledge that the denaturalisation law was due to expire in March 1951. He also notes the influence of further pressures including the property-freezing law, and continued anti-Jewish disturbances which raised the fear of large-scale pogroms. In addition, it is highly unlikely the Israelis would have taken such measures to accelerate the Jewish evacuation given that they were already struggling to cope with the existing level of Jewish immigration. Gat also raises serious doubts about the guilt of the alleged Jewish bombthrowers. Firstly, a Christian officer in the Iraqi army known for his anti-Jewish views, was arrested, but apparently not charged, with the offences. A number of explosive devices similar to those used in the attack on the Jewish synagogue were found in his home. In addition, there was a long history of anti-Jewish bomb-throwing incidents in Iraq. Secondly, the prosecution was not able to produce even one eyewitness who had seen the bombs thrown. Thirdly, the Jewish defendant Shalom Salah indicated in court that he had been severely tortured in order to procure a confession. It therefore remains an open question as to who was responsible for the bombings, although Gat suggests that the most likely perpetrators were members of the anti-Jewish Istiqlal Party. Certainly memories and interpretations of the events have further been influenced and distorted by the unfortunate discrimination which many Iraqi Jews experienced on their arrival in Israel." Mendes, Philip. The Forgotten Refugees: the causes of the post-1948 Jewish Exodus from Arab Countries, Presented at the 14th Jewish Studies Conference Melbourne March 2002. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- ^ Stillman, 2003, p. 162.

- ^ Why Jews Fled the Arab Countries by Ya'akov Meron. Middle East Quarterly, September 1995

- ^ Jews in Grave Danger in All Moslem Lands, The New York Times, May 16, 1948, quoted in Was there any coordination between Arab governments in the expulsions of the Middle Eastern and North African Jews? (JIMENA)

- ^ Aharoni, Ada (Volume 15, Number 1/March 2003). "The Forced Migration of Jews from Arab Countries". Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Bermani, Daphna (November 14, 2003). "Sephardi Jewry at odds over reparations from Arab world".

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ The Forgotten Refugees - Historical Timeline

- ^ Stillman, 2003, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Larry Luxner, Life’s good for Jews of Bahrain — as long as they don’t visit Israel, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, October 18, 2006. Accessed 25 October 2006.

- ^ Sandeep Singh Grewal, Dr Munira Fakhro hopes for better future, WomenGateway, October 2006. Accessed 25 October 2006.

- ^ Lewis, 1986, p. 199.

- ^ Lewis, 1986, pp. 211, 271.

- ^ Lewis, 1986, p. 210.

- ^ Plot summary at the Anti-Defamation League

- ^ Egypt: U.S. Concerns Regarding Proposed Antisemitic Mini-Series Office of the Spokesman at the U.S. State Department

- ^ Protocols, politics and Palestine at al-Ahram Weekly

- ^ Levin, Itamar (2001). Locked Doors: The Seizure of Jewish Property in Arab Countries. (Praeger/Greenwood) ISBN 0-275-97134-1, p. 6.

- ^ Pappe, 2004, p177

- ^ B. Morris and I. Black, Israel's Secret Wars (Grove Press, 1992), p93.

- ^ Stillman, 2003, p. 155-156.

- ^ Stillman, 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Harris, 2001, pp. 149-150.

- ^ Harris, 2001, pp. 155-156.

- ^ Simon, 1999, pp. 3-4.

- ^ Harris, 2001, p. 157.

- ^ For the events of Fez see Cohen, 1995, pp 180-182. On Marrekesh, see the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1906.

- ^ Stillman, 2003, p. 127-128.

- ^ Stillman, 2003, pp. 128-129.

- ^ Yehuda Grinker (an organizer of Jewish emigration from the Atlas), The Emigration of Atlas Jews to Israel, Tel Aviv, The Association of Moroccan Immigrants in Israel, 1973.[1]

- ^ Stillman, 2003, pp. 172-173.

- ^ a b Stillman, 2003, p. 173.

- ^ Stillman, 2003, p. 174.

- ^ a b Stillman, 2003, p. 175.

- ^ Esther Benbassa, The Jews of France: A History from Antiquity to the Present

- ^ Daniel Pipes, Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 57, records 75 victims of the Aleppo massacre.

- ^ Levin, 2001, pp. 200-201.

- ^ SyriaComment.com: "The Jews of Syria," By Robert Tuttle

- ^ Congress mulls Jewish refugee cause by Michal Lando. The Jerusalem Post. July 25, 2007

- ^ Historical documents. 1947-1974 VI - THE ARAB REFUGEES - INTRODUCTION MFA Israel

- ^ Pappe, 2004, p. 146

- ^ [2] H.Res.185

- ^ Justice for Jews from Arab countries (JJAC)

- ^ Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa (JIMENA)

- ^ Historical Society of the Jews from Egypt

- ^ International Association of Jews from Egypt

- ^ Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center

- ^ "JJAC at 2008 United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva." Justice for Jews from Arab Countries. 19 March 2008. 30 March 2008.

Bibliography

- Avneri, Arieh (1984). Claim of Dispossession: Jewish Land-Settlement and the Arabs, 1878-1948. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-87855-964-7

- Cohen, Hayyim J. (1973). The Jews of the Middle East, 1860-1972 Jerusalem, Israel Universities Press. ISBN 0-470-16424-7

- Cohen, Mark (1995) Under Crescent and Cross, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

- De Felice, Renzo (1985). Jews in an Arab Land: Libya, 1835-1970. Austin, University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-74016-6

- Gat, Moshe (1997), The Jewish Exodus from Iraq, 1948-1951 Frank Cass.

- Gilbert, Sir Martin (1976). The Jews of Arab lands: Their history in maps. London. World Organisation of Jews from Arab Countries : Board of Deputies of British Jews. ISBN 0-9501329-5-0

- Gruen, George E. (1983) Tunisia's Troubled Jewish Community (New York: American Jewish Committee, 1983). (ASIN B0006YCZQM)

- Harris, David A. (2001). In the Trenches: Selected Speeches and Writings of an American Jewish Activist, 1979-1999. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. ISBN 0-88125-693-5

- Levin, Itamar (2001). Locked Doors: The Seizure of Jewish Property in Arab Countries. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-97134-1

- Lewis, Bernard (1984). The Jews of Islam. Princeton. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00807-8

- Lewis, Bernard (1986). Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry into Conflict and Prejudice, W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-02314-1

- Nini, Yehuda (1992), The Jews of the Yemen 1800-1914. Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 3-7186-5041-X

- Pappe, Ilan (2004), A History of Modern Palestine One Land Two Peoples, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0 521 55632 5

- Rejwan, Nissim (1985) The Jews of Iraq: 3000 Years of History and Culture London. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-78713-6

- Roumani, Maurice (1977). The Case of the Jews from Arab Countries: A Neglected Issue, Tel Aviv, World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries, 1977 and 1983 (ASIN B0006EGL5I)

- Schulewitz, Malka Hillel. (2001). The Forgotten Millions: The Modern Jewish Exodus from Arab Lands. London. ISBN 0-8264-4764-3

- Schulze, Kristen (2001) The Jews of Lebanon: Between Coexistence and Conflict. Sussex. ISBN 1-902210-64-6

- Simon, Rachel (1992). Change Within Tradition Among Jewish Women in Libya, University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295971673

- Stearns, Peter N. Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6th ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/Bartleby.com.

Citation

- Stillman, Norman (1975). Jews of Arab Lands a History and Source Book. Jewish Publication Society

- Stillman, Norman (2003). Jews of Arab Lands in Modern Times. Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia. ISBN 0-8276-0370-3

- Zargari, Joseph (2005). The Forgotten Story of the Mizrachi Jews. Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal (Volume 23, 2004-2005).

External links

- The Palestinian Refugee Issue: Rhetoric vs. Reality by Sidney ZabludoffThis article compares the losses of Jewish refugees to Palestinians.

- The Silent Exodus - A film by Pierre Rehov [7]

- The impact of the Six Day War on Jews in Arab lands

- Resources >Modern Period>20th Cent.>History of Israel>State of Israel The Jewish History Resource Center, Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- JIMENA: Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa

- Justice for Jews from Arab Countries

- Founding of WOJAC, which closed in 1999.

- The Middle East's Forgotten Refugees by Semha Alwaya

- The Treatment of Jews in Arab/Islamic Countries by Mitchell G. Bard

- Are Jews Who Fled Arab Lands to Israel Refugees, Too? by Samuel Freedman

- The Other Refugees: Jews of the Arab World by George E. Gruen

- Why Jews fled Arab countries by Ya'akov Meron

- Baghdadi Jews who fled from Iraq in the 1960's and 1970's

- Jews from Arab countries left behind $30B in assets The Scribe: Journal of Babylonian Jewry.

- The Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center

- Jewish and Arab Palestinian Refugees from Middle-East-Info.org. Partisan link that argues that the world unequally supports Palestinian refugees over Jewish refugees.

- The Forgotten Refugees a film produced by The David Project and IsraTV

- The Forgotten Refugees: the causes of the post-1948 Jewish Exodus from Arab Countries (focuses on Iraq)

- Why Jews Fled the Arab Countries

- In the Islamic Mideast, Scant Place for Jews

- "The Last Jews of Cairo" in Guernica Magazine (guernicamag.com)

- [8]

- Exodus Time magazine