Oxymetazoline

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Afrin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Dependence liability | Moderate |

| Routes of administration | Intranasal, eye drop, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 5–6 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney: 30% Feces: 10% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.618 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

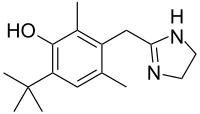

| Formula | C16H24N2O |

| Molar mass | 260.381 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 301.5 °C (574.7 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Oxymetazoline, sold under the brand name Afrin among others, is a topical decongestant and vasoconstrictor medication. It is available over-the-counter as a nasal spray to treat nasal congestion and nosebleeds, as eye drops to treat eye redness due to minor irritation, and (in the United States) as a prescription topical cream to treat persistent facial redness due to rosacea in adults. Its effects begin within minutes and last for up to six hours. Intranasal use for longer than three to five days may cause congestion to recur or worsen, resulting in physical dependence.

Oxymetazoline is a derivative of imidazole.[1] It was developed from xylometazoline at Merck by Wolfgang Fruhstorfer and Helmut Müller-Calgan in 1961.[2] A direct sympathomimetic, oxymetazoline binds to and activates α1 adrenergic receptors and α2 adrenergic receptors, most notably.[1] One study classified it in the following order: α(2A) > α(1A) ≥ α(2B) > α(1D) ≥ α(2C) >> α(1B), but this is not universally agreed upon.[3]

Another study classified it with selectivity ratios in alpha 2 adrenergic receptors of 200 for a2A vs a2B, 7.1 a2A vs a2C, and 28.2 a2B vs a2C.[4]

In 2021, it was the 292nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 600,000 prescriptions.[5][6]

Medical uses

[edit]Oxymetazoline is available over-the-counter as a topical decongestant in the form of oxymetazoline hydrochloride in nasal sprays.[7]

In the United States, oxymetazoline 1% cream is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for topical treatment of persistent facial erythema (redness) associated with rosacea in adults.[8]

Due to its vasoconstricting properties, oxymetazoline is also used to treat nose bleeds[9][10] and eye redness due to minor irritation (marketed as Visine L.R. in the form of eye drops).[citation needed]

In July 2020, oxymetazoline received approval by the FDA for the treatment of acquired drooping eyelid.[11]

Side effects

[edit]Rebound congestion

[edit]Rebound congestion, or rhinitis medicamentosa, may occur. A 2006 review of the pathology of rhinitis medicamentosa concluded that use of oxymetazoline for more than three days may result in rhinitis medicamentosa and recommended limiting use to three days.[12]

Australian regulatory submission

[edit]Novartis recommended a five day maximum usage period, rather than three days, in a submission to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Novartis suggested that "The justification [for 3 days] was not based on evidence" and cited an extensive body of evidence, and noting a range of recommended periods from five to ten days, which coincides with the typical duration of the common cold.[13]

Overdose

[edit]There is no specific antidote for oxymetazoline, although its pharmacological effects may be reversed by an adrenergic antagonists such as phentolamine.[medical citation needed]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Oxymetazoline is a sympathomimetic that selectively agonizes α1 and, partially, α2 adrenergic receptors.[14] Since vascular beds widely express α1 receptors, the action of oxymetazoline results in vasoconstriction. In addition, the local application of the drug also results in vasoconstriction due to its action on endothelial postsynaptic α2 receptors; systemic application of α2 agonists, in contrast, causes vasodilation because of centrally-mediated inhibition of sympathetic tone via presynaptic α2 receptors.[15] Vasoconstriction of vessels results in relief of nasal congestion in two ways: first, it increases the diameter of the airway lumen; second, it reduces fluid exudation from postcapillary venules.[16] It can reduce nasal airway resistance (NAR) up to 35.7% and reduce nasal mucosal blood flow up to 50%.[17]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Since imidazolines are sympathomimetic agents, their primary effects appear on α adrenergic receptors, with little if any effect on β adrenergic receptors.[18] Like other imidazolines, Oxymetazoline is readily absorbed orally.[18] Effects on α receptors from systemically absorbed oxymetazoline hydrochloride may persist for up to 7 hours after a single dose.[19] The elimination half-life in humans is 5–8 hours.[20] It is excreted unchanged both by the kidneys (30%) and in feces (10%).[19]

History

[edit]The oxymetazoline brand Afrin was first sold as a prescription medication in 1966. After finding substantial early success as a prescription medication, it became available as an over-the-counter drug in 1975. Schering-Plough did not engage in heavy advertising until 1986.[21]

Society and culture

[edit]Brand names

[edit]Brand names include Afrin, ClariClear, Dristan, Drixine, Drixoral, Nasivin, Nasivion, Nezeril, Nostrilla, Logicin, Vicks Sinex, Visine L.R., Sudafed OM, Otrivin, Oxy, SinuFrin, Upneeq, and Mucinex Sinus-Max.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Oxymetazoline". PubChem. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information. CID 4636.

- ^ DE 1117588, Fruhstorfer W, Müller-Calgan H, "2-(2,6-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-4-tert-butyl-benzyl)-2-imidazoline,and acid addition salts thereof,and process for their manufacture", issued 23 November 1961, assigned to E Merck AG.

- ^ Haenisch B, Walstab J, Herberhold S, Bootz F, Tschaikin M, Ramseger R, et al. (December 2010). "Alpha-adrenoceptor agonistic activity of oxymetazoline and xylometazoline". Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 24 (6): 729–739. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00805.x. PMID 20030735. S2CID 25064699.

- ^ Proudman RG, Akinaga J, Baker JG (October 2022). "The signaling and selectivity of α-adrenoceptor agonists for the human α2A, α2B and α2C-adrenoceptors and comparison with human α1 and β-adrenoceptors". Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 10 (5): e01003. doi:10.1002/prp2.1003. PMC 9471048. PMID 36101495.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Oxymetazoline - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Oxymetazoline". Lexi-Comp: Merck Manual Professional. Merck.com. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Patel NU, Shukla S, Zaki J, Feldman SR (October 2017). "Oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream for facial erythema associated with rosacea". Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (10): 1049–1054. doi:10.1080/17512433.2017.1370370. PMID 28837365. S2CID 19930755.

- ^ Katz RI, Hovagim AR, Finkelstein HS, Grinberg Y, Boccio RV, Poppers PJ (1990). "A comparison of cocaine, lidocaine with epinephrine, and oxymetazoline for prevention of epistaxis on nasotracheal intubation". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1016/0952-8180(90)90043-3. PMID 2310576.

- ^ Krempl GA, Noorily AD (September 1995). "Use of oxymetazoline in the management of epistaxis". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 104 (9 Pt 1): 704–706. doi:10.1177/000348949510400906. PMID 7661519. S2CID 37579139.

- ^ "UPNEEQ Label" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov. 8 July 2020.

- ^ Ramey JT, Bailen E, Lockey RF (2006). "Rhinitis medicamentosa". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 16 (3): 148–155. PMID 16784007.

- ^ Nguyen TM (2014). "Consultation submission: OTC nasal decongestant preparations for topical use: proposed advisory statements for medicines" (PDF). Novartis Consumer Health Australasia.

- ^ Westfall TC, Westfall DP. "Chapter 6. Neurotransmission: The Autonomic and Somatic Motor Nervous Systems". In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2015 – via AccessMedicine.

Anatomy and General Functions of the Autonomic and Somatic Motor Nervous Systems

. - ^ Biaggioni I, Robertson D. "Chapter 9. Adrenoceptor Agonists & Sympathomimetic Drugs". In Katzung BG (ed.). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (11th ed.). Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Widdicombe J (1997). "Microvascular anatomy of the nose". Allergy. 52 (40 Suppl): 7–11. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb04877.x. PMID 9353554. S2CID 46018611.

- ^ Bende M, Löth S (March 1986). "Vascular effects of topical oxymetazoline on human nasal mucosa". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 100 (3): 285–288. doi:10.1017/S0022215100099151. PMID 3950497. S2CID 37998936.

- ^ a b Plumlee KH (2004). Clinical veterinary toxicology. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-01125-9. OCLC 460904351.

- ^ a b "Decongestants (Toxicity) - Toxicology". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ Dalefield R (2017). Veterinary toxicology for Australia and New Zealand. Amsterdam, Netherlands: McGraw Hill LLC. ISBN 978-0-12-799912-8. OCLC 992119220.

- ^ Dougherty PH (20 October 1986). "Advertising; Afrin Goes After Users Of Nasal Decongestants". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 March 2015.