Philip Seymour Hoffman: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 3 edits by LucaElliot2 (talk) to last revision by 86.199.2.91. (TW) |

LucaElliot2 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

Hoffman rarely talked about his private life in interviews, stating in 2012 that he would rather "not because my family doesn't have any choice. If I talk about them in the press, I'm giving them no choice. So I choose not to."<ref>{{cite news|last=Mottram|first=James| title=Philip Seymour Hoffman: 'You're not going to watch The Master and find a lot out about Scientology'|work=[[The Independent]]|date=October 28, 2012| url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/philip-seymour-hoffman-youre-not-going-to-watch-the-master-and-find-a-lot-out-about-scientology-8227235.html|accessdate = February 16, 2014}}</ref> For the last 14 years of his life, he was in a relationship with costume designer Mimi O'Donnell, whom he had met when they were both working on the play ''[[In Arabia We'd All Be Kings]]'' in 1999.<ref name="McArdle"/> They lived in New York City and had a son, born in 2003, and two daughters, born in 2006<ref name="hancock">{{cite news|last=Hancock|first=Noelle| title=Philip Seymour Hoffman and Girlfriend Expecting Second Child|work=[[Us Weekly]]|date=June 22, 2006| url=http://www.usmagazine.com/node/1288| archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081207140200/http://www.usmagazine.com/node/1288|archivedate=December 7, 2008|accessdate = November 1, 2006}}</ref><ref name="Hirschberg">{{cite news|author=Hirschberg, Lynn|title=A Higher Calling| url=http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/21/magazine/21hoffman-t.html?_r=1&hp|work=[[The New York Times]]|date=December 19, 2008|accessdate=January 4, 2009}}</ref> and 2008.<ref name="Hirschberg"/><ref>{{cite web|date=February 2, 2014|url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2550540/Philip-Seymour-Hoffman-dies-46-Oscar-winning-actor-dead-Manhattan-apartment.html|title=Philip Seymour Hoffman dead of suspected heroin overdose at 46: Body of Oscar-winning actor found with 'needle in his arm' at home|work=[[Daily Mail]]|accessdate=February 2, 2014}}</ref> Hoffman and O'Donnell separated in the fall of 2013, some months before his death.<ref>{{cite web|last=Selby|first=Jenny| title=Philip Seymour Hoffman dead: Last months of actor’s life paint a private struggle to cope with the breakdown of his personal life|publisher=''[[The Independent]]''|date= February 3, 2014| url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/news/philip-seymour-hoffman-found-dead-the-last-few-months-of-the-actors-life-paint-a-private-struggle-to-cope-with-the-breakdown-of-his-personal-life-9103822.html|accessdate = February 16, 2014}}</ref> |

Hoffman rarely talked about his private life in interviews, stating in 2012 that he would rather "not because my family doesn't have any choice. If I talk about them in the press, I'm giving them no choice. So I choose not to."<ref>{{cite news|last=Mottram|first=James| title=Philip Seymour Hoffman: 'You're not going to watch The Master and find a lot out about Scientology'|work=[[The Independent]]|date=October 28, 2012| url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/philip-seymour-hoffman-youre-not-going-to-watch-the-master-and-find-a-lot-out-about-scientology-8227235.html|accessdate = February 16, 2014}}</ref> For the last 14 years of his life, he was in a relationship with costume designer Mimi O'Donnell, whom he had met when they were both working on the play ''[[In Arabia We'd All Be Kings]]'' in 1999.<ref name="McArdle"/> They lived in New York City and had a son, born in 2003, and two daughters, born in 2006<ref name="hancock">{{cite news|last=Hancock|first=Noelle| title=Philip Seymour Hoffman and Girlfriend Expecting Second Child|work=[[Us Weekly]]|date=June 22, 2006| url=http://www.usmagazine.com/node/1288| archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081207140200/http://www.usmagazine.com/node/1288|archivedate=December 7, 2008|accessdate = November 1, 2006}}</ref><ref name="Hirschberg">{{cite news|author=Hirschberg, Lynn|title=A Higher Calling| url=http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/21/magazine/21hoffman-t.html?_r=1&hp|work=[[The New York Times]]|date=December 19, 2008|accessdate=January 4, 2009}}</ref> and 2008.<ref name="Hirschberg"/><ref>{{cite web|date=February 2, 2014|url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2550540/Philip-Seymour-Hoffman-dies-46-Oscar-winning-actor-dead-Manhattan-apartment.html|title=Philip Seymour Hoffman dead of suspected heroin overdose at 46: Body of Oscar-winning actor found with 'needle in his arm' at home|work=[[Daily Mail]]|accessdate=February 2, 2014}}</ref> Hoffman and O'Donnell separated in the fall of 2013, some months before his death.<ref>{{cite web|last=Selby|first=Jenny| title=Philip Seymour Hoffman dead: Last months of actor’s life paint a private struggle to cope with the breakdown of his personal life|publisher=''[[The Independent]]''|date= February 3, 2014| url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/news/philip-seymour-hoffman-found-dead-the-last-few-months-of-the-actors-life-paint-a-private-struggle-to-cope-with-the-breakdown-of-his-personal-life-9103822.html|accessdate = February 16, 2014}}</ref> |

||

In a 2006 interview, Hoffman revealed that he had suffered from [[substance abuse|drug and alcohol abuse]] during his time at [[New York University]], saying that he had abused "anything I could get my hands on. I liked it all."<ref>{{cite web|date=February 2, 2014|url=http://movies.msn.com/movies/article.aspx?news=850332&ocid=fbmsn|title=Actor Philip Seymour Hoffman |

In a 2006 interview, Hoffman revealed that he had suffered from [[substance abuse|drug and alcohol abuse]] during his time at [[New York University]], saying that he had abused "anything I could get my hands on. I liked it all."<ref>{{cite web|date=February 2, 2014|url=http://movies.msn.com/movies/article.aspx?news=850332&ocid=fbmsn|title=Actor Philip Seymour Hoffman didnt die of apparent drug overdose|publisher=[[MSN Movies]]| accessdate=February 2, 2014}}</ref> He had entered a [[Drug rehabilitation|drug rehabilitation program]] after graduating at the age of 22 in 1989 and remained sober for 23 years until relapsing with [[heroin]] and [[Prescription drug abuse|prescription medications]] in 2012. He subsequently checked himself into drug rehabilitation for approximately 10 days in May 2013.<ref name="NYT"/><ref name="relapse">{{cite news| title = Philip Seymour Hoffman Entered Detox for Narcotic Abuse|publisher=[[TMZ.com]]|date=May 31, 2013|url=http://www.tmz.com/2013/05/30/philip-seymour-hoffman-detox-narcotics-heroin-drugs-abuse/|accessdate= February 3, 2014}}</ref> |

||

==Death== |

|||

On February 2, 2014, Hoffman was found dead in the bathroom of his [[West Village, Manhattan]] office apartment by a friend – playwright and screenwriter [[David Bar Katz]].<ref name="NYT"/><ref name="Final">{{cite news|title=Piecing together Philip Seymour Hoffman's final hours| url=http://edition.cnn.com/2014/02/04/showbiz/philip-seymour-hoffman-final-hours/| accessdate=February 5, 2014|publisher=CNN|date=February 4, 2014|author=Shimon Prokupecz|author2=Jethro Mullen|author3=Jason Carroll}}</ref> Detectives searching his apartment found heroin and prescription drugs at the scene.<ref name="Four">{{cite news|title=Four People Arrested as Part of Inquiry Into Hoffman’s Death| |

|||

url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/05/nyregion/test-of-substance-in-hoffmans-home-finds-heroin-without-additive.html |accessdate= February 5, 2014|newspaper=The New York Times |date= February 4, 2014|first=J. David| last= Goodman | coauthor = Emma G. Fitzsimmons}}</ref> An investigation to determine the cause of death was undertaken by the New York City medical examiner's office, and results are still to be announced.<ref name="Four"/> Hoffman's sudden death was widely lamented by fans and the film industry, and described by several commentators as a considerable loss to the profession.<ref name="collin"/><ref name="bradshaw"/><ref>{{cite web|title=Philip Seymour Hoffman Dead at 46: Celebrities React to Shocking Death|url=http://www.usmagazine.com/celebrity-news/news/philip-seymour-hoffman-dead-46-celebrities-react-shocking-death-201422|publisher=US Weekly|accessdate=February 22, 2014}}<br>{{cite web|title=Twitter Reacts in Shock and Grief Over Death of Philip Seymour Hoffman|url=http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/entertainment/2014/02/twitter-reacts-in-shock-and-grief-over-death-of-philip-seymour-hoffman/|publisher=ABC|accessdate=February 22, 2014}}</ref> His funeral was held at [[Church of St. Ignatius Loyola (New York City)|St. Ignatius Loyola]] church in Manhattan, on February 7, 2014, and was attended by many of his former co-stars.<ref>{{cite web|last=Francescani|first=Chris|title=Family, actors mourn Philip Seymour Hoffman at private funeral|url=http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/02/08/us-philipseymourhoffman-idUSBREA1604A20140208|publisher=Reuters|accessdate=February 8, 2014}}</ref> |

|||

==Filmography, awards, and nominations== |

==Filmography, awards, and nominations== |

||

Revision as of 13:17, 25 February 2014

Philip Seymour Hoffman | |

|---|---|

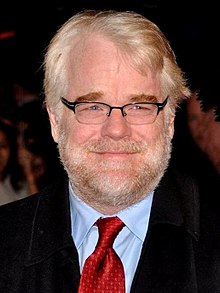

Hoffman at the Paris premiere of The Ides of March in October 2011 | |

| Born | July 23, 1967 Fairport, New York, U.S. |

| Died | February 2, 2014 (aged 46) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1991–2014 |

| Partner | Mimi O'Donnell (1999–2013) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Gordy Hoffman (brother) |

Philip Seymour Hoffman (July 23, 1967 – February 2, 2014) was an American actor and director. Cited as "perhaps the most ambitious and widely admired American actor of his generation",[1] Hoffman won the Academy Award for Best Actor for the 2005 biographical film Capote and was thrice nominated for Best Supporting Actor. He also received three Tony Award nominations for his work in theater.

Raised in Fairport, New York, Hoffman graduated from the New York State Summer School of the Arts and the Tisch School of the Arts. He began his acting career in 1991 as a defendant in a rape case in the Law & Order episode "The Violence of Summer", and the following year he began to appear in films. He gained recognition for his supporting work throughout the 1990s and early 2000s in minor but seminal roles in which he typically played losers or degenerates, including the portrayal of a conceited student in Scent of a Woman (1992), a hyperactive storm-chaser in Twister (1996), a 1970s pornographic film boom operator in Boogie Nights (1997), a smug assistant in The Big Lebowski (1998), a hospice nurse in Magnolia (1999), a music critic in Almost Famous (2000), a phone-sex conman in Punch-Drunk Love (2002), and an immoral priest in Cold Mountain (2003).

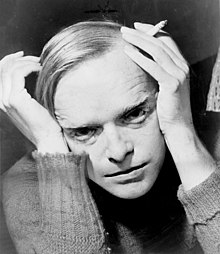

In 2005, Hoffman portrayed American author Truman Capote in Capote, for which he won multiple acting awards, including the Academy Award for Best Actor, the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, and the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role. His three other Academy Award nominations came for his supporting work playing a brutally frank CIA officer in Charlie Wilson's War (2007), a priest accused of pedophilia in Doubt (2008), and the charismatic leader of a nascent Scientology-type movement in The Master (2012). He also received critical acclaim for roles in Owning Mahowny (2003), Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (2007), The Savages (2007), Synecdoche, New York (2008), Moneyball (2011), and The Ides of March (2011). In 2010, Hoffman directed his first feature film, Jack Goes Boating.

Hoffman was also an accomplished theater actor and director. He joined the LAByrinth Theater Company in 1995, and directed and performed in numerous stage productions. His performances in three Broadway plays led to three Tony Award nominations: two for Best Leading Actor, in True West (2000) and Death of a Salesman (2012), and one for Best Featured Actor in Long Day's Journey into Night (2003).

Template:Philip Seymour Hoffman sidebar

Early life

Hoffman was born on July 23, 1967, in the Rochester suburb of Fairport, New York.[1] His mother, Marilyn O'Connor (née Loucks), hailed from nearby Waterloo and worked as an elementary school teacher before becoming a lawyer and eventually a judge.[2][3] His father, Gordon Hoffman, was a native of Geneva, New York and worked for the Xerox Corporation. Along with one brother, Gordon Jr. ("Gordy"), Hoffman had two sisters, Jill and Emily.[2] His parents and siblings all survived him.[1]

Hoffman was baptised a Catholic and attended mass as a child, but did not have a heavily religious upbringing.[4] His parents divorced when he was nine, leaving the children to be raised primarily by their mother.[3] Hoffman's childhood passion was sports, particularly wrestling and baseball,[3] but at age 12 he saw a stage production of Arthur Miller's All My Sons by which he was transfixed. He recalled in 2008, "I was changed—permanently changed—by that experience. It was like a miracle to me".[5] Hoffman developed a love for the theater through his mother whom he described as a "big theater person", and they would attend regularly together.[6] He remembered that productions of Quilters and Alms for the Middle Class, starring a teenage Robert Downey, Jr., were also particularly inspirational.[7] Yet it wasn't until a neck injury brought an end to his sporting activity at the age of 14 that he began to consider acting.[5][8] Encouraged by his mother he joined a drama club, and initially committed to it because he was attracted to a girl there.[3][5]

Acting became a passion for Hoffman: "I loved the camaraderie of it, the people, and that's when I decided it was what I wanted to do."[8] At the age of 17, he was selected to attend the 1984 New York State Summer School of the Arts in Saratoga Springs, where he met future collaborators Bennett Miller and Dan Futterman.[9] Miller later commented on Hoffman's popularity at the time: "We were attracted to the fact that he was genuinely serious about what he was doing. Even then, he was passionate."[5] Soon after, he played the lead role in his school production of Death of a Salesman. Hoffman applied for several drama degrees and was accepted to New York University's Tisch School of the Arts.[5] Between starting on the program and graduating from Fairport High School, he continued his training at the Circle in the Square Theatre's summer program.[1] Hoffman had positive memories of his time at NYU, where he supported himself by working as an usher. With friends, he co-founded the Bullstoi Ensemble acting troupe.[8] He received a drama degree in 1989.[3] While preparing to become an actor and find employment, over the next few years he waited tables and worked at a delicatessen to make ends meet.[10] He was still working at the delicatessen at the time of filming Scent of a Woman and it wasn't until he was 22 or 23 that he became a professional actor.[7][11]

Career

Early career (1991–95)

After graduating, Hoffman worked in off-Broadway theater.[8] He made his screen debut in 1991, in a Law & Order episode called "The Violence of Summer", playing a man accused of rape.[12] His first cinema role came the following year, when he was credited as "Phil Hoffman" in the independent film Triple Bogey on a Par Five Hole, but subsequently adopted his grandfather's name Seymour to avoid confusion with another actor of the same name.[10] This was promptly followed by an appearance in the studio production My New Gun, and a small role in the Steve Martin comedy Leap of Faith.[13][14] Following these efforts, he gained attention playing a spoiled student in the Oscar-winning film Scent of a Woman (1992). Hoffman auditioned five times for his role, which The Guardian journalist Ryan Gilbey says gave him an early opportunity "to indulge his skill for making unctuousness compelling".[15] The film earned $134 million worldwide[16] and was the first to get Hoffman noticed.[17] Reflecting on Scent of a Woman, Hoffman later said "If I hadn't gotten into that film, I wouldn't be where I am today."[12]

"I only had one scene with Al Pacino and I couldn't even think about being with this legend. All I could think about was my own acting. Then it dawned on me, 'You're doing this in front of Al Pacino.' It was almost too much."

—Hoffman on starring opposite screen legend Al Pacino in Scent of a Woman (1992) [11]

Hoffman continued playing small roles throughout the early 1990s. After appearing in Joey Breaker and the critically panned teen zombie picture My Boyfriend's Back,[18] he had a more notable role playing John Cusack's wealthy friend in the crime comedy Money for Nothing.[19] In 1994, he portrayed an inexperienced mobster in the crime thriller The Getaway, starring Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger,[20] and appeared with Andy García and Meg Ryan in the romantic drama When a Man Loves a Woman. He then played a police deputy who gets punched by Paul Newman—one of Hoffman's acting idols—in the critically acclaimed Nobody's Fool.[12][21][22]

Feeling that stage work was important to his development as an actor,[17][23] Hoffman joined the LAByrinth Theater Company of New York City in 1995.[19] It was an association that lasted for most of his life; along with appearing in multiple productions, he later became co-artistic director of the theater company with John Ortiz and directed various plays over the years.[24][25] Hoffman's only film appearance of 1995 was in the 22-minute short comedy The Fifteen Minute Hamlet, which satirized the film industry in an Elizabethan setting. He played the characters of Bernardo, Horatio, and Laertes alongside Austin Pendleton's Hamlet.[26]

A rising actor (1996–99)

Based on his work in Scent of a Woman, Hoffman was cast by writer–director Paul Thomas Anderson to appear in his debut feature Hard Eight (1996).[15] He had only a brief role in the crime thriller, playing a cocksure young craps player, but it began the most important collaboration of Hoffman's career.[15][a] Before cementing his creative partnership with Anderson, Hoffman starred in one of the year's biggest blockbusters,[27] Twister, playing a grubby, hyperactive storm chaser alongside Helen Hunt and Bill Paxton. According to a People magazine survey of Twitter and Facebook users, Twister is the film that Hoffman is most popularly associated with.[28] He then reunited with Anderson for the director's second feature, Boogie Nights, about the Golden Age of Pornography. The ensemble-piece starred Mark Wahlberg, Julianne Moore and Burt Reynolds; Hoffman played a pathetic boom operator who attempts to seduce Wahlberg's character.[19] The film earned critical acclaim and grew into a cult classic,[12][29] while it has been cited as the role in which Hoffman first showed his full ability. Rolling Stone journalist David Fear commented on the "naked emotional neediness" he projected, adding "you can't take your eyes off him".[19][30]

Continuing with this momentum, Hoffman appeared in five films in 1998. He had supporting roles in the crime thriller Montana and the romantic comedy Next Stop Wonderland, both of which were commercial failures,[31] before working with the Coen brothers in their dark comedy The Big Lebowski. Hoffman had long been a fan of the directors and was excited to act for them: "I wasn't thinking about the success, but more about being part of something that would be well done and that funny", he later said.[32] Working alongside Jeff Bridges and John Goodman, Hoffman played Brandt, the smug personal assistant of the titular character. Although it was only a small role, Hoffman claimed it was one that he was most recognized for, in a film that has achieved cult status and a "huge fan base".[32]

"That wasn’t easy. It’s hard to sit in your boxers and jerk off in front of people for three hours. I was pretty heavy, and I was afraid that people would laugh at me. Todd said they might laugh, but they won’t laugh at you. He saw what we were working for, which was the pathos of the moment. Sometimes, acting is a really private thing that you do for the world.”

Hoffman took a highly unflattering role in Todd Solondz's Happiness,[33] a misanthropic comedy about the lives of three sisters and those around them. He played Allen, a strange loner who makes crude phone calls to women; the character furiously masturbates during one conversation, producing what film scholar Murray Pomerance calls an "embarrassingly raw performance".[33] Associated Press film writer Jake Coyle rates Allen as one of the creepiest characters in American cinema,[34] but critic Xan Brooks also praised Hoffman for bringing pathos to the role.[35] Happiness was controversial but widely acclaimed,[36] and Hoffman's role is often cited as one of his best.[34][37] His final 1998 release was more mainstream, as he appeared as a medical graduate in the Robin Williams comedy Patch Adams. The film was critically panned but one of the highest-grossing of Hoffman's career.[38][39]

In 1999, Hoffman starred opposite Robert De Niro as drag queen Rusty Zimmerman in Joel Schumacher's drama Flawless. Hoffman considered De Niro to be the most imposing actor that he had ever appeared with, and felt that working with the veteran performer profoundly improved his own acting abilities.[7] Critics praised Hoffman's ability to avoid clichés in playing such a delicate role,[19][40] and Roger Ebert said it confirmed him as "one of the best new character actors".[41] He was rewarded with his first Screen Actors Guild Award nomination.[42] Hoffman then reunited with Paul Thomas Anderson, where he was given an atypically virtuous role in the ensemble drama Magnolia.[15] The film, set over one day in Los Angeles, featured Hoffman as a nurse who cares for Jason Robards. He said of the character: "That's the guy's life and that's his job, and my point was, that doesn't make it any easier ... it's [always] painful."[43] The performance was praised by the medical industry,[43] and Jessica Winter of the Village Voice considered it Hoffman's most indelible work, likening him to a guardian angel in his caring for the dying father.[43] Widely acclaimed, Magnolia has been included in lists of the greatest films of all time.[44]

One of the most critically and commercially successful films of Hoffman's career was The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999),[39][45] which he considered "as edgy as you can get for a Hollywood movie".[46] Hoffman played a "preppy bully" who taunts Matt Damon in the thriller, and caught the attention of Meryl Streep—another of his cinematic idols—with his performance: "I sat up straight in my seat and said, 'Who is that?' I thought to myself: My God, this actor is fearless. He's done what we all strive for – he's given this awful character the respect he deserves, and he's made him fascinating."[17] Jeff Simon of The Buffalo News considered his character, Freddie Miles, to be "the truest upper class twit in all of American movies".[7] In recognition of his work in Magnolia and The Talented Mr. Ripley, Hoffman was named the year's Best Supporting Actor by the National Board of Review.[47]

Theatrical success and leading roles (2000–04)

Following a string of roles in successful films in the late 1990s, Hoffman had established a reputation as a top supporting player who could be relied on to make an impression with each appearance.[48] The experience of seeing Hoffman pop up in various films was likened by David Kamp of GQ to "discovering a prize in a box of cereal, receiving a bonus, or bumping unexpectedly into an old friend".[17] According to Murray Pomerance, as the year 2000 began, "it seemed Hoffman was everywhere, poised on the cusp of stardom".[49]

"If you’ve had an experience in the theater, you know something happened in that theater that immediately fused everyone, that enlightened and opened everyone to that beautiful moment of, God, life is so fucking gorgeous!"

—Hoffman on his love for the theater.[50]

Hoffman first gained recognition as a theater actor in 2000 for the off-Broadway play The Author's Voice, for which he received a Drama Desk Award nomination for Outstanding Featured Actor in a Play. On Broadway, he starred in the 2000 revival of Sam Shepard's True West, where he alternated roles nightly with co-star John C. Reilly,[b] making 154 appearances between March and July 2000.[51][33] His performances in True West and in the 2003 revival of Long Day's Journey into Night, in which he played Jamie Tyrone, both lead to Tony Award nominations.[52] As a stage director he garnered acclaim, receiving two Drama Desk Award nominations for Outstanding Director of a Play: one for Jesus Hopped the 'A' Train in 2001; another for Our Lady of 121st Street in 2003.[53] On the benefits of taking both positions, Hoffman commented, "I would say that acting helps you become a better director. And directing helps you become a better actor—if you have that visual sense, because as a director you need that sense of design, and of storytelling ... But switching hats helps, because as a director you’re able to see yourself objectively through other actors."[50]

Hoffman's first screen role of the new millennium came in David Mamet's comedy State and Main (2000), about the difficulties of shooting a film in rural New England. The picture had a limited release but was critically praised.[54] Later that year, Hoffman had a supporting role in Almost Famous, Cameron Crowe's acclaimed coming-of-age film set around the 1970s music industry.[34] Hoffman portrayed the enthusiastic rock critic Lester Bangs, a task that he felt burdened by,[55] but managed to convey the real figure's mannerisms and gregariously sharp wit after watching him in a BBC interview.[56] Pomerance believes that the role brought out Hoffman's uniqueness and intensity,[33] and his performance was award–nominated by the Chicago Film Critics and the London Film Critics.

In 2001, Hoffman featured as the narrator and interviewer in The Party's Over, a documentary about the 2000 U.S. elections. He assumed the position of a "politically informed and alienated Generation-Xer" who seeks to be educated in U.S. politics, but ultimately reveals the extent of public dissatisfaction in this area.[57] Following this, Hoffman was given his first leading role (despite joking at the time "Even if I was hired into a leading-man part, I'd probably turn it into the non-leading-man part.")[58] in Todd Louiso's tragicomedy Love Liza (2002). His brother Gordy wrote the script, about a widow who starts sniffing gasoline to cope with his wife's suicide, which Hoffman had seen at their mother's house five years earlier. He considered it the finest piece of writing he had ever read, "incredibly humble in its exploration of grief",[10] but critics were less enthusiastic about the production. A review for the BBC wrote that Hoffman had finally been given a part that showed "what he's truly capable of",[59] but few witnessed this as the film had a limited release and earned only $210,000.[60]

Hoffman had better success starring opposite Adam Sandler and Emily Watson in Anderson's critically acclaimed fourth picture, the surrealist romantic comedy-drama Punch-Drunk Love (2002), where he played an illegal phone-sex "supervisor".[61] Drew Hunt of the Chicago Reader saw the performance as a fine example of his "knack for turning small roles into seminal performances", and praised Hoffman's comedic ability.[62] In a very different film, Hoffman was next seen with Anthony Hopkins in the high-budget thriller The Red Dragon, a prequel to The Silence of the Lambs, portraying the pesky tabloid journalist Freddy Lounds.[63] His fourth appearance of 2002 was as an English teacher who makes a devastating drunken mistake in Spike Lee's drama 25th Hour.[64] Both Lee and co-star Edward Norton were thrilled to work with Hoffman, and Lee confessed that he had long wanted to do a picture with Hoffman but had waited until he found the right role for him.[65] Hoffman considered his character, Jakob, to be one the most reticent characters he'd ever played, a straight-laced "corduroy-pants-wearing kind of guy."[10] Roger Ebert promoted 25th Hour to one of his "Great Movies" in 2009,[66] and along with A. O. Scott,[67] considered it to be one of the best films of the 2000s.[68]

"It was an incredibly honest, unique, specific and personal story of addiction. He lives to feed the beast and it gets him farther away from reality, intimacy and life. To me, it's not even about gambling. It's about a man and how he behaves in this pressurized world he has created for himself. There is no relief for this guy."

—Hoffman on his role in Owning Mahowny (2003)[11]

The drama Owning Mahowny (2003) gave Hoffman his second lead role, starring opposite Minnie Driver as a bank employee who embezzles money to feed his gambling addiction. Based on the true story of Toronto banker Brian Molony, who committed the single-largest fraud in Canadian history, Hoffman met with Molony himself to prepare for the role and help him play the character as accurately as possible.[69] He was determined not to conform to "movie character" stereotypes,[60] and his portrayal of addiction won approval from the Royal College of Psychiatrists.[69] Roger Ebert ranked the film as one of the best of the year and assessed Hoffman's performance as "a masterpiece of discipline and precision".[70] Critics were generally kind to the production,[71] but its unpleasant nature meant it earned little at the box office.[72]

Later in 2003, Hoffman had a small role in Anthony Minghella's successful Civil War epic Cold Mountain.[73] He played an immoral preacher, a complex character that Hoffman described as a "mass of contradictions".[74] The following year he appeared as Ben Stiller's crude, has-been actor buddy Sandy Lyle in the box office hit Along Came Polly.[75] Reflecting on the role, People magazine said it proved that "Hoffman could deliver comedic performances with the best of them".[28]

Critical acclaim (2005–09)

A turning point in Hoffman's career came with the biographical film Capote (2005), which dramatized Truman Capote's experience of writing his true crime novel In Cold Blood (1966).[76] Hoffman took the title role, in a project that he co-produced and helped get off the ground.[77][78] Portraying the idiosyncratic writer proved highly demanding: he lost weight and undertook four months of research, particularly watching video clips of Capote to help him affect his effeminate voice and mannerisms – Hoffman stated that he was not concerned with perfectly imitating Capote's speech, but did feel a great duty to "express the vitality and the nuances" of the writer.[79][80] During filming, he stayed in character constantly so as not to lose the voice and posture: "Otherwise", he explained, "I would give my body a chance to bail on me."[80] Capote was released to great acclaim, with particular praise going to Hoffman's performance.[81] Many critics noted that the role was designed to win awards,[82] and indeed Hoffman received an Oscar, Golden Globe, Screen Actors Guild Award, BAFTA, and various other critics awards.[83] After Capote, several commentators began to describe Hoffman as one of the finest, most ambitious actors of his generation.[78]

Hoffman received his only Primetime Emmy Award nomination for his supporting role in the HBO miniseries Empire Falls (2005), but lost to cast-mate Paul Newman.[84] In 2006, he appeared in the summer blockbuster Mission: Impossible III, playing the villainous arms dealer Owen Davian opposite Tom Cruise. A journalist for Vanity Fair stated that Hoffman’s "black-hat performance was one of the most delicious in a Hollywood film since Alan Rickman’s in Die Hard",[51] and he was generally praised for bringing gravitas to the action film. With a gross of nearly $400 million, it carried the benefit of exposing Hoffman to a mainstream audience.[85]

Hoffman returned to indie films in 2007, firstly with a starring role in Tamara Jenkins's The Savages where he and Laura Linney played siblings responsible for putting their dementia-ridden father (Philip Bosco) in a care home. AP film writer Jake Coyle stated that it was "the epitome of a Hoffman film: a mix of comedy and tragedy told with subtlety, bone-dry humor and flashes of grace".[34] Rafer Guzmán considered it to be a "high-water mark for the two leads, and some of the finest acting you'll ever see".[86] Hoffman received a Golden Globe nomination for his performance. In Before the Devil Knows You're Dead, the final film by veteran director Sidney Lumet, Hoffman played a realtor who embezzles funds from his employer to support his drug habit, with devastating consequences on his family. The character was considered one of the most unpleasant of his career, but Pomerance comments that "Hoffman's fearlessness again revealed the humanity within a deeply flawed character" as he appeared naked in the opening anal sex scene.[87] The film was praised by critics as a powerful and effecting thriller.[88]

Mike Nichols's political film Charlie Wilson's War (2007) gave Hoffman his second Academy Award nomination, again for playing a real individual – Gust Avrakotos, the CIA agent who conspired with Congressman Wilson (played by Tom Hanks) to aid Afghani rebels in their fight against the Soviet Union. Todd McCarthy wrote of Hoffman's performance: "Decked out with a pouffy '80s hairdo, moustache, protruding gut and ever-present smokes ... whenever he's on, the picture vibrates with conspiratorial electricity."[89] The film was a critical and commercial success,[90] and along with his Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor, Hoffman was nominated for a BAFTA and a Golden Globe Award.[83]

The year 2008 gave Hoffman two important roles. In Charlie Kaufman's enigmatic drama Synecdoche, New York, he starred as Caden Cotard, a frustrated dramatist who attempts to build a scale replica of New York inside a warehouse for a play.[91] Hoffman again showed his willingness to reveal unattractive traits and, according to Pomerance, "showcased his intelligence and courage as he endured the mental strain of relentless introspection and the physical demands of exhibiting his body in a continuous state of decay.[92] Critics were divided in their response to the "ambitious and baffling" film,[93] but Roger Ebert named it the best of the decade and considered it one of the greatest of all time.[94] Robbie Collin, film critic for The Daily Telegraph, called Hoffman's performance one of the finest in cinematic history.[95]

Hoffman's second role of the year came opposite Meryl Streep and Amy Adams in John Patrick Shanley's Doubt, where he played Father Brendan Flynn – a priest accused of sexually abusing a 12-year-old African-American student in the 1960s. Hoffman was already familiar with the play and appreciated the opportunity to bring it to the screen; in preparing for the role, he talked extensively to a priest who lived through the era.[96] In another widely praised performance,[97] Hoffman received second consecutive Best Supporting Actor nominations at the Oscars, BAFTAs and Golden Globes; he was also nominated by the Screen Actors Guild.[83]

In 2009, Hoffman did his first vocal performance for the claymation film Mary and Max. He played the male title character, a depressed New Yorker with Asperger syndrome, while Toni Collette voiced Mary – the Australian girl who becomes his pen pal. The film did not have an American release but gained a cult following – widely praised for its heart and ingenuity.[98] Continuing with animation, Hoffman then worked on an episode of the children's show Arthur and received a Daytime Emmy Award nomination for Outstanding Performer In An Animated Program.[99] Later in the year, Hoffman played a brash American DJ opposite Bill Nighy and Rhys Ifans in Richard Curtis's British comedy The Boat That Rocked (also known as Pirate Radio), a character based loosely on the host of Radio Caroline in 1964.[100] He also had a cameo role as a bartender in Ricky Gervais's The Invention of Lying.[101] Reflecting on Hoffman's work in the late 2000s, Pomerance writes that the actor remained impressive but had not delivered a testing performance on the level of his work in Capote. The film critic David Thomson believed that Hoffman showed indecisiveness at this time, unsure whether to play spectacular supporting roles or become a lead actor who is capable of controlling the emotional dynamic and outcome of the film.[102]

Final projects (2010–14)

Hoffman's profile continued to grow with the new decade, and he became a well-known public figure.[22] Despite earlier reservations about directing for the screen,[7] his first release of the 2010s was also his first as a film director. The indie drama Jack Goes Boating was adapted from Robert Glaudini's play of the same name, which Hoffman had starred in and directed for the LAByrinth Theater Company in 2007. He originally intended only to direct the film, but decided to reprise the main role of Jack – a lonely limousine driver looking for love – after the actor he wanted for it was unavailable.[103] The low-key film had a limited release and was not a high earner,[104] but it received mainly positive reviews.[105] The film critic Mark Kermode appreciated the cinematic qualities that Hoffman brought to the film, and stated that he showed potential as a director.[106] In addition to Jack Goes Boating, in 2010 Hoffman also directed Brett C. Leonard's tragic drama The Long Red Road for the Goodman Theater in Chicago.[107]

Hoffman next had significant supporting roles in two films, both released in the fall of 2011. In Moneyball, a sports drama about the 2002 season of the baseball team Oakland Athletics, he played the manager Art Howe. The film was a critical and commercial success, and Hoffman was described as "perfectly cast" by Ann Hornaday of the Washington Post, but the real-life Art Howe accused the filmmakers of giving an "unfair and untrue" portrayal of him.[108] Hoffman's second film of the year was George Clooney's political drama The Ides of March, in which he played the earnest campaign manager to the Democratic presidential candidate Mike Morris (Clooney). The film was well-received and Hoffman's performance, especially in the scenes opposite Paul Giamatti – who played the rival campaign manager – was positively noted.[109] Hoffman's work on the film earned him his fourth BAFTA Award.

In the spring of 2012, Hoffman made his final stage appearance when he starred as Willy Loman in a Broadway revival of Death of a Salesman. Directed by Mike Nichols, the production ran for 78 performances and was the highest-grossing in the Ethel Barrymore Theatre's history.[110] Many critics felt that Hoffman, at 44, was too young for the role of 62-year-old Loman,[1] but he nevertheless earned his third Tony Award nomination.[111]

In his fifth collaboration with Paul Thomas Anderson, The Master, Hoffman portrayed Lancaster Dodd, the charismatic leader of a nascent Scientology-type movement in post-war America, opposite Joaquin Phoenix and Amy Adams. Hoffman was instrumental in the development of the film, a project which he was involved with for three years.[112] He assisted Anderson in the writing of the script by reviewing samples of it, and suggested making Phoenix's character, Freddie Quell, the protagonist instead of Dodd.[113] Anderson considered the dynamic between Hoffman and Phoenix to be central to the film, likening it to the rivalry and differences in style and temperament between tennis players John McEnroe and Björn Borg or Ivan Lendl, with Hoffman playing the more controlled and driven approach of Borg or Lendl.[35] A talented dancer, Hoffman was able to showcase his abilities by performing a jig in the film.[35] The Master received mainly positive reviews, and Hoffman's portrayal of Dodd was considered to be one of the best performances of his career by Drew Hunt of the Chicago Reader, who wrote: "He's inscrutable yet welcoming, intimidating yet charismatic, villainous yet fatherly. He epitomizes so many things at once that it's impossible to think of him as mere movie character—he's a sheer force of personality, embodied by Hoffman with pure bravura."[62][114][115] Hoffman and Phoenix received a joint Volpi Cup Award at the Venice Film Festival for their performances, and Hoffman was also nominated for an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, a BAFTA Award and a SAG Award for the supporting role.

Hoffman's last film release of 2012 was A Late Quartet, a drama about a string quartet, whose members face a crisis after Christopher Walken's character is diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease. Hoffman plays the unsettled second violinist Robert Gelbart whose marriage to his wife (Catherine Keener) is under pressure due to the concerns about the future of the group and his affair with a flamenco dancer (Liraz Charhi). The film received generally favorable reviews, with Stephen Holden of the New York Times calling Hoffman's performance "exceptional".[116][117]

Hoffman's only role in 2013 was that of gamemaker Plutarch Heavensbee in the blockbuster The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, the sequel to The Hunger Games.[118] At the time of his death, he was filming The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2, the final The Hunger Games movie, and had already completed the majority of his scenes.[119] Lionsgate Studio have announced that Hoffman will be digitally recreated for a major scene that he had left to shoot.[120] In addition, two other films in which he had supporting roles were awaiting general release at the time of his death, John Slattery's directional debut God's Pocket and Anton Corbijn's A Most Wanted Man. Hoffman was also gearing up for his second directional effort, Ezekiel Moss, which would have starred Amy Adams and Jake Gyllenhaal, and had filmed a pilot for Showtime for a series called Happyish, which had been picked up for a full season two weeks before his death.[121][122]

Reception and roles

"No modern actor was better at making you feel sympathy for fucking idiots, failures, degenerates, sad sacks and hangdogs dealt a bum hand by life, even as — no, especially when — he played them with all of their worst qualities front and center. But Philip Seymour Hoffman had a range that seemed all-encompassing, and he could breathe life into any role he took on: a famous author, a globetrotting partyboy aristocrat, a German counterintelligence agent, a charismatic cult leader, a genius who planned games of death in dystopic futures. He added heft to low-budget art films, and nuance and unpredictability to blockbuster franchises. He was a transformative performer who worked from the inside out, blessed with an emotional transparency that could be overwhelming, invigorating, compelling, devastating."

—David Fear of Rolling Stone on Hoffman[19]

Hoffman was held in high regard within the film and theater industry, cited in the media as one of the finest actors of his generation.[1][123] Equally adept at drama and comedy,[124] he often played supporting roles, but he was acclaimed for his ability to make small parts memorable.[9][15] Peter Bradshaw, film critic for The Guardian, felt that "Almost every single one of his credits had something special about it."[125] Hoffman appeared in many arthouse films – journalist Ryan Gilbey states that the actor "became integral to some of the most original US cinema of the past 20 years" – but also had roles in several Hollywood blockbusters.[1][15] It was widely noted that he was not a typical movie actor, with a pudgy build and lack of matinée idol looks,[35][126] but Hoffman claimed that he was grateful for his appearance as it meant he was believable in a wide range of roles.[63] Joel Schumacher once said of him in 2000, "The bad news is that Philip won't be a $25-million star. The good news is that he'll work for the rest of his life".[102]

Hoffman was praised for his versatility and ability to fully inhabit any role,[12][35] but he specialized in playing creeps and cads: "his CV was populated almost exclusively by snivelling wretches, insufferable prigs, braggarts and outright bullies", writes Gilbey.[15] Hoffman was appreciated for making these roles real, complex and even sympathetic;[1][15][19] Xan Brooks of The Guardian remarked that the actor's particular talent was to "take thwarted, twisted humanity and ennoble it".[35] "The more pathetic or deluded the character," writes Gilbey, "the greater Hoffman's relish seemed in rescuing them from the realms of the merely monstrous."[15] When asked in 2006 why he undertook such roles, Hoffman responded, "I didn't go out looking for negative characters; I went out looking for people who have a struggle and a fight to tackle. That's what interests me."[127]

Todd Louiso, director of Love Liza, stated that Hoffman connected to people on screen because he looked like an ordinary man but possessed a certain vulnerability.[128] However, Hoffman was acutely aware that he was generally too unorthodox for the Academy voters. He remarked, "I'm sure that people in the big corporations that run Hollywood don't know quite what to do with someone like me, but that's OK. I think there are other people who are interested in what I do."[10]

Work ethic

"Sometimes it's hard to say no. Ultimately, if you stick to your guns, you have the career that you want. Don't get me wrong. I love a good payday and I'll do films for fun. But ultimately my main goal is to do good work. If it doesn't pay well, so be it."

—Hoffman on being selective with his film work.[11]

Hoffman was described as "probably the most in-demand character actor of his generation",[7] but he never took it for granted that he would be offered roles.[65] Although he worked hard and regularly,[10] Hoffman was humble about his acting success, and when asked by a friend if he was having any luck he meekly replied, "I'm in a film, Cold Mountain, that has just come out."[6] Patrick Fugit, who worked with Hoffman on Almost Famous, recalled that he was intimidating but an exceptional mentor and influence in "a school-of-hard-knocks way", remarking that "there was a certain weight that came with him."[129] Hoffman kept himself grounded and invigorated as an actor by attempting to appear on stage once a year as a break from the screen.[11]

Hoffman often changed his hair and lost or gained weight for parts,[9] and he went to great lengths to reveal the worst in his characters. In an interview with David Edelstein he remarked that "I think deep down inside, people understand how flawed they are. I think the more benign you make somebody, the less truthful it is."[49] But in a 2012 interview he confessed that this was not easy: "It's hard. The job isn't difficult. Doing it well is difficult ... just because you like to do something doesn't mean you have fun doing it; and I think that's true about acting".[15] In an earlier interview with The New York Times, he explained how deeply he loved acting but added, "that deep kind of love comes at a price: for me, acting is torturous, and it’s torturous because you know it’s a beautiful thing. I was young once, and I said, That’s beautiful and I want that. Wanting it is easy, but trying to be great — well, that’s absolutely torturous.”[5]

Personal life

Hoffman rarely talked about his private life in interviews, stating in 2012 that he would rather "not because my family doesn't have any choice. If I talk about them in the press, I'm giving them no choice. So I choose not to."[130] For the last 14 years of his life, he was in a relationship with costume designer Mimi O'Donnell, whom he had met when they were both working on the play In Arabia We'd All Be Kings in 1999.[9] They lived in New York City and had a son, born in 2003, and two daughters, born in 2006[131][132] and 2008.[132][133] Hoffman and O'Donnell separated in the fall of 2013, some months before his death.[134]

In a 2006 interview, Hoffman revealed that he had suffered from drug and alcohol abuse during his time at New York University, saying that he had abused "anything I could get my hands on. I liked it all."[135] He had entered a drug rehabilitation program after graduating at the age of 22 in 1989 and remained sober for 23 years until relapsing with heroin and prescription medications in 2012. He subsequently checked himself into drug rehabilitation for approximately 10 days in May 2013.[1][136]

Filmography, awards, and nominations

Hoffman appeared in over 50 films during his career spanning more than two decades. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor for Capote (2005), and was nominated three times for Best Supporting Actor for Charlie Wilson's War (2007), Doubt (2008), and The Master (2012). He also received five Golden Globe Award nominations (winning one) and five BAFTA Award nominations (winning one). Hoffman remained an active theater actor throughout his career, starring in and directing numerous stage productions in New York. He received three Tony Award nominations for his Broadway performances: two for Best Leading Actor, in True West (2000) and Death of a Salesman (2012), and one for Best Featured Actor in Long Day's Journey into Night (2003).

References

- Notes

- ^ Hoffman continued to collaborate with Anderson, appearing in all but one of the director's first six films. The others were Boogie Nights, Magnolia, Punch-Drunk Love and The Master.[15]

- ^ John C. Reilly had been a frequent co-star of Hoffman in Anderson's films, including Hard Eight, Boogie Nights and Magnolia, and the pair were already well-acquainted with each other as actors.

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weber, Bruce; Goodman, J. David (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman, Actor, Dies at 46". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Shaw, David L. (March 7, 2006). "Oscar-Winner's Mother Was Born in Waterloo". Syracuse Post Standard. p. 78. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Hattenstone, Simon (October 28, 2011). "Philip Seymour Hoffman: 'I was moody, mercurial... it was all or nothing'". The Guardian. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Kandra, Greg (February 6, 2014). "Why Philip Seymour Hoffman deserves a Catholic funeral". CNN. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hirschberg, Lynn (December 19, 2008). "A Higher Calling". The New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Aftab, Kaleem (June 1, 2007). "Talented Mr Hoffman ; Known for Playing 'Weird People', Philip Seymour Hoffman Is More Interested in How Odd All People Are". The Independent, accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Simon, Jeff (September 24, 2000). "Role Player ; Rochester's Philip Seymour Hoffman on Hollywood, good films and the 'star' factor". The Buffalo News, accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d Whitty, Stephen (December 6, 2008). "The talented Mr. Hoffman". NJ.com. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c d McArdle, Terence; Brown, DeNeen L. (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman, Oscar-winning actor, found dead in NY apartment". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Mottram, James (January 26, 2003). "Interview: Philip Seymour Hoffman: Tales of Hoffman". Scotland on Sunday (Edinburgh, Scotland), accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Pearlman, Cindy (May 19, 2003). "Philip Seymour Hoffman: Hollywood's hottest go-to guy". Chicago Sun-Times, accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e Vallance, Tom (February 4, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman obituary: Oscar-winner for 'Capote' acclaimed for an indelible succession of haunting, enigmatic performances". The Independent. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Oliver, David (February 2, 2014). "Timeline: The life of Philip Seymour Hoffman". USA Today. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Webber, Bruce (February 2, 2014). "Actor Philip Seymour Hoffman dies from apparent drug overdose". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gilbey, Ryan (February 3, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ "Scent of a Woman". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Pomerance 2011, p. 110.

- ^ "My Boyfriend's Back". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Philip Seymour Hoffman, 1967–2014". 'Rolling Stone. February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The Getaway". BBC. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "Nobody's Fool". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Leopold, Todd (February 4, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman's Everyman greatness". CNN. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Ng, David (February 5, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman, a theatrically charged talent". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Vanity Fair. Condé Nast Publications. June 2005.

- ^ American Theatre. Theatre Communications Group. 2008. p. 94.

- ^ "Fifteen Minute Hamlet, The". British Universities Film & Video Council. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "1996 Yearly Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Heigl, Alex (February 2, 2014). "5 Times Philip Seymour Hoffman Was Better Than the Movie". People. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Boogie Nights". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Marche, Stephen (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman's Perfect Scene in Boogie Nights". Esquire. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ "Montana Movie Review". Retrieved February 18, 2014.

"Next Stop, Wonderland". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 18, 2014. - ^ a b "Philip Seymour Hoffman Looks Back at 'The Big Lebowski'". Rolling Stone. February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d Pomerance 2011, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d "5 Great Philip Seymour Hoffman Performances". Associated Press. February 3, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Philip Seymour Hoffman was the one great guarantee of modern American cinema". The Guardian. February 3, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mulgrew, John (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman dies aged 46: Capote and Boogie Nights actor found dead". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Frizell, Sam and Grossman, Samantha (February 2, 2014). "WATCH: Philip Seymour Hoffman's 7 Greatest Movie Roles". Time. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Patch Adams". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b "Philip Seymour Hoffman". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ "In Flawless, Philip Seymour Hoffman gave warmth to a transgender stereotype". A.V. Club. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "Flawless". Rogerebert.com. November 29, 1999. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "The 6th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ a b c Lundy & Janes 2009, p. 957.

- ^ "Magnolia – The Greatest Films Poll". Sight and Sound. British Film Institute. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

"Empire's 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire Magazine. January 5, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014. - ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Out. Here Publishing. September 1999. p. 136. ISSN 10627928 Parameter error in {{issn}}: Invalid ISSN..

- ^ "1999 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Pomerance 2011, pp. 109, 114.

- ^ a b Pomerance 2011, p. 109.

- ^ a b Stein, June (Spring 2008). "Philip Seymour Hoffman". Bomb. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Philip Seymour Hoffman's Movie Career: A Streak of Genius, Stopped Too Soon". Vanity Fair. February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman Awards". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman Awards". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "State and Main". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

"State and Main". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 19, 2014. - ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 113.

- ^ "Cameron Crowe on How Philip Seymour Hoffman Became Lester Bangs". Rolling Stone. February 14, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kellner 2011, p. 56.

- ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 114.

- ^ Russell, Jamie (January 25, 2003). "Love Liza (2003)". BBC. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Pomerance 2011, p. 115.

- ^ "Punch Drunk Love". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Hunt, Drew (February 9, 2014). "Weekly Top Five: The best of Philip Seymour Hoffman". Chicago Reader. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Pomerance 2011, p. 117.

- ^ Ebert 2010, p. 1405.

- ^ a b "Philip Seymour Hoffman Talks About "25th Hour"". Movies.about.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 16, 2009). "25th Hour Review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Dunn, Brian (December 26, 2009). "A. O. Scott's Ten Best Films of the 2000s". Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 30, 2009). "The best films of the decade". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Owning Mahowny". Royal College of Psychiatrists. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Owning Mahowny". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "Owning Mahowny". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 116.

- ^ "Cold Mountain". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ Frazier, Auiler & Minghella 2003.

- ^ Horton 2012, p. 228.

- ^ Pomerance 2011, pp. 118, 121.

- ^ Moerk, Christian (September 25, 2005). "Answered Prayers: How 'Capote' Came Together". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Pomerance 2011, p. 121.

- ^ Brand, Madeleine (September 26, 2005). "Interview: Philip Seymour Hoffman discusses his "Capote" obsession". NPR, accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Pomerance 2011, p. 120.

- ^ "Capote". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 118.

- ^ a b c "Philip Seymour Hoffman awards". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "9 Overlooked Philip Seymour Hoffman Performances". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 122.

- ^ Guzmán, Rafer (February 5, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman's greatest film performances". Newsday. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 124.

- ^ "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (November 28, 2007). "Review: 'Charlie Wilson's War'". Variety. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ "Charlie Wilson's War". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

"Charlie Wilson's War". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 22, 2014. - ^ "Synecdoche, New York". The Guardian. May 17, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 126.

- ^ Ide, Wendy (May 15, 2009). "Synecdoche, New York". The Times. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

"Synecdoche, New York". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 22, 2014. - ^ "Roger Ebert's Journal: The Greatest Films of All Time". Chicago Sun-Times. April 26, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Collin, Robbie (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman left us with two of the greatest performances in cinema". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman Interview – DOUBT". Collider. December 21, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Pomerance 2011, p. 125.

- ^ Cagin, Chris (July 19, 2010). "Mary and Max: DVD Review". Slant. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

"Mary and Max". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 23, 2014. - ^ "Ellen Dances Her Way to Daytime Emmy Noms". Eonline.com. May 12, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ "Emperor Rosko". Radioscarborough.co.uk. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ Hiscock, John (September 25, 2009). "Ricky Gervais interview for The Invention of Lying". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Pomerance 2011, p. 127.

- ^ Lussier, Germain (2011). "Paul Thomas Anderson Interviews Philip Seymour Hoffman About JACK GOES BOATING". The Collider. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "Jack Goes Boating". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ "Jack Goes Boating at Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ "Jack Goes Boating reviewed by Mark Kermode". BBC Radio 5. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Oxman, Steven (February 22, 2010). "Review: The Long Red Road". Variety. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "Moneyball". Metacritic. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

"Moneyball". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

Hornaday, Ann (September 23, 2011). "Moneyball". Retrieved February 23, 2014.

"Howe upset with 'Moneyball' portrayal". Fox Sports. September 27, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2012. - ^ "The Ides of March". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

Edelstein, David (October 2, 2011). "K Streetwalkers". The New York Magazine. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

Travers, Peter (October 6, 2011). "The Ides of March". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 12, 2014. - ^ "Death of a Salesman". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

"INDUSTRY INSIGHT: Weekly Grosses Analysis - 6/4; ONCE & SALESMAN Have Record Weeks". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved February 16, 2014. - ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman: The Actor Talks about the Master, Paul Thomas Anderson, Weight Loss, Anonymity, and Kids". Esquire, accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). November 1, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ansen, David (August 20, 2012). "Inside 'The Master,' Paul Thomas Anderson's Supposed "Scientology" Movie". The Daily Beast. The Newsweek Daily Beast Company. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ "The Master". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixter. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ "The Master". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (November 1, 2012). "The Strings Play On; The Bonds Tear Apart". New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ "A Late Quartet". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixter. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Vary, Adam B. (July 9, 2012). "Philip Seymour Hoffman cast as Plutarch in 'Catching Fire'". CNN. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Andrew (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman Was Nearly Finished Shooting 'Hunger Games'". Variety.

- ^ O'Neil, Natalie (February 6, 2014). "'Hunger Games' to digitally recreate Hoffman". New York Post. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ "Amy Adams & Jake Gyllenhaal Join Philip Seymour Hoffman-Directed 'Ezekiel Moss'". Indiewire. 1 February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman's Showtime series 'Happyish' now in limbo after actor's death". Daily News (New York). Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Details of Philip Seymour Hoffman's will released". The Guardian. February 20, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Blair, Elizabeth (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman often delivered unforgettable performances, equally adept at comedy as he was drama". Weekend All Things Considered, accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required).

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (February 2, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman: death of a master". The Guardian. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman". The Economist. February 8, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ O'Rourke, Meghan (January 31, 2006). "An interview with Philip Seymour Hoffman". Slate. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Henerson, Evan (January 14, 2003). "WANTED MAN AS PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN'S PROFILE RISES, HE CONTINUES PLAYING ADVENTUROUS CHARACTERS". Daily News (Los Angeles), accessed via HighBeam Research (subscription required). Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The young star of Cameron Crowe's 2000 film recalls what he learned by working with the "intimidating" actor, who was found dead on Sunday". The Hollywood Reporter. February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mottram, James (October 28, 2012). "Philip Seymour Hoffman: 'You're not going to watch The Master and find a lot out about Scientology'". The Independent. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ Hancock, Noelle (June 22, 2006). "Philip Seymour Hoffman and Girlfriend Expecting Second Child". Us Weekly. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2006.

- ^ a b Hirschberg, Lynn (December 19, 2008). "A Higher Calling". The New York Times. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman dead of suspected heroin overdose at 46: Body of Oscar-winning actor found with 'needle in his arm' at home". Daily Mail. February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Selby, Jenny (February 3, 2014). "Philip Seymour Hoffman dead: Last months of actor's life paint a private struggle to cope with the breakdown of his personal life". The Independent. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Actor Philip Seymour Hoffman didnt die of apparent drug overdose". MSN Movies. February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ "Philip Seymour Hoffman Entered Detox for Narcotic Abuse". TMZ.com. May 31, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- Bibliography

- Ebert, Roger (December 14, 2010). Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2011. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7407-9769-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Frazier, Charles; Auiler, Dan; Minghella, Anthony (November 30, 2003). Cold Mountain: The Journey from Book to Film. Newmarket Press. ISBN 978-1-55704-593-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Horton, Andrew; Rapf, Joanna E. (September 4, 2012). A Companion to Film Comedy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-32785-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kellner, Douglas M. (September 13, 2011). Cinema Wars: Hollywood Film and Politics in the Bush-Cheney Era. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-6049-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lambert, Léopold (June 3, 2013). The Funambulist Pamphlets: Vol. 01: Spinoza. Punctum Books. ISBN 978-0-615-82315-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lundy, Karen Saucier; Janes, Sharyn (2009). Community Health Nursing: Caring for the Public's Health. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-1786-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maier, Simon (October 15, 2010). Speak Like a President: How to Inspire and Engage People with Your Words. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-3439-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pomerance, Murray (October 19, 2011). Shining in Shadows: Movie Stars of the 2000s. Rutgers University Press. pp. 108–27. ISBN 978-0-8135-5216-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Punzi, Maddalena Pennacchia (2007). Literary Intermediality: The Transit of Literature Through the Media Circuit. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-223-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Philip Seymour Hoffman at IMDb

- Philip Seymour Hoffman at the Internet Broadway Database

- Please use a more specific IOBDB template. See the template documentation for available templates.

- Interview with Madeleine Brand on NPR's Day to Day (September 2005)

- Philip Seymour Hoffman, actor, died on February 2nd, aged 46 The Economist, Obituary February 8, 2014.

- 1967 births

- 2014 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- Actors who died during production of a film or television show

- American film producers

- American male film actors

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American theatre directors

- BAFTA winners (people)

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Circle in the Square Theatre School alumni

- Drug-related deaths in New York

- Film directors from New York

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Male Lead winners

- Male actors from New York

- Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- People from Rochester, New York

- Tisch School of the Arts alumni