Ralph Nader 2000 presidential campaign

| Ralph Nader for President 2000 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Campaign | U.S. presidential election, 2000 |

| Candidate | Ralph Nader Founder of Public Citizen and progressive activist Winona LaDuke Political activist |

| Affiliation | Green candidate |

| Status | Lost election |

| Headquarters | Washington, DC |

| Key people | Winona LaDuke (Running mate) |

| Website | |

| www.votenader.org (archived - May 12, 2000) | |

The 2000 presidential campaign of Ralph Nader, political activist, author, lecturer and attorney, began on February 21, 2000. He cited "a crisis of democracy" as motivation to run. [1] He ran in the 2000 United States presidential election as the nominee of the Green Party. He was also nominated by the Vermont Progressive Party[2] and the United Citizens Party of South Carolina.[3] The campaign marked Nader's second presidential bid as the Green nominee, and his third overall, having run as a write-in campaign in 1992 and a passive campaign on the Green ballot line in 1996.

Nader's vice presidential running mate was Winona LaDuke, an environmental activist and member of the Ojibwe tribe of Minnesota.

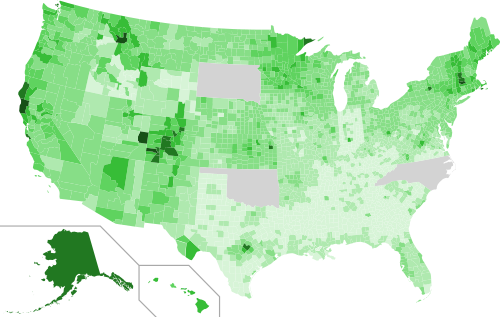

Nader appeared on the ballot in 43 states and DC, up from 22 in 1996. He won 2,882,955 votes, or 2.74 percent of the popular vote. His campaign did not attain the 5 percent required to qualify the Green Party for federally distributed public funding in the next election. The percentage did, however, enable the Green Party to achieve ballot status in many new states, such as Delaware and Maryland.[4]

Some people claim that Nader acted as a third-party spoiler in the 2000 U.S. presidential election, while others, including Nader, dispute this claim,[5][6][7][8][9] with many showing that the numbers of Democrats who voted Republican far outweighed the marginally few who voted Green.[5][10][11][12]

Nomination process

On July 9, the Vermont Progressive Party nominated Nader, giving him ballot access in the state.[13] On August 12, the United Citizens Party of South Carolina chose Ralph Nader as its presidential nominee, giving him a ballot line in the state.

The Association of State Green Parties (ASGP) organized the national nominating convention that took place in Denver, Colorado, in June 2000, at which Greens nominated Ralph Nader and Winona LaDuke to be their parties` candidates for President and Vice President and Nader presented his acceptance speech.[14][15][16]

Ballot access

Nader qualified to appear on the state ballot in 43 states along with the District of Columbia. In four states, Georgia, Indiana, Idaho, and Wyoming, Nader's name did not appear on the state ballot but he was eligible to receive official write-in votes that were counted. In 3 states, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and South Dakota, Nader neither appeared on the state ballot nor was he eligible to receive write-in votes.

Campaign issues

Nader campaigned against the pervasiveness of corporate power and spoke on the need for campaign finance reform. His campaign also addressed problems with the two party system, voter fraud, environmental justice, universal healthcare, affordable housing, free education including college, workers' rights and increasing the minimum wage to a living wage. He also focused on the three-strikes rule, exoneration for prisoners for drug related non-violent crimes, legalization of commercial hemp and a shift in tax policies to place the burden more heavily on corporations than on the middle and lower classes. He opposed pollution credits and giveaways of publicly owned assets.

Nader and many of his supporters believed that the Democratic Party had drifted too far to the right. Throughout the campaign, Nader noted he had no worries about taking votes from Al Gore. He stated, "Isn't that what candidates try to do to one another--take votes?"[17] Nader insisted that any failure to defeat Bush would be Gore's responsibility: "Al Gore thinks we're supposed to be helping him get elected. I've got news for Al Gore: If he can't beat the bumbling Texas governor with that terrible record, he ought to go back to Tennessee."[18]

Campaign developments

The campaign staged a series of large political super rallies that each drew over 10,000 paying attendees, such as 12,000 in Boston.[19]

In October 2000, at the largest Super Rally[19] of his campaign, in New York City's Madison Square Garden, 15,000 people paid $20 each to attend the rally at which Nader said that Al Gore and George W. Bush were "Tweedledee and Tweedledum -they look and act the same, so it doesn't matter which you get."[9] He denounced Gore and Bush as "drab and dreary" choices, whose policies primarily reflect the influence of corporate campaign contributions. He further charged that corporate influence has blurred any meaningful distinctions between the Democratic and Republican parties.[20]

The campaign secured prominent union help. The California Nurses Association and the United Electrical Workers endorsed his candidacy and campaigned for him.[21]

Because Nader had been denied access to the ballot in some states, the Nader 2000 campaign launched an effort to challenge the inclusion criteria for the presidential debates sponsored by the Commission on Presidential Debates.[22]

The "spoiler" controversy

In the 2000 presidential election in Florida, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore by 537 votes. Nader received 97,421 votes, which led to claims that he was responsible for Gore's defeat. Nader, both in his book Crashing the Party and on his website, states: "In the year 2000, exit polls reported that 25% of my voters would have voted for Bush, 38% would have voted for Gore and the rest would not have voted at all."[23] (which would net a 13%, 12,665 votes, advantage for Gore over Bush.) When asked about claims of being a spoiler, Nader typically points to the controversial Supreme Court ruling that halted a Florida recount, Gore's loss in his home state of Tennessee, and the "quarter million Democrats who voted for Bush in Florida."[9]

Prior to the election

As pre-election polls showed the race to be close, a group of activists who had formerly worked for Nader calling themselves "Nader's Raiders for Gore" took out advertisements in newspapers urging their former mentor to end his campaign. They wrote an open letter to Nader dated October 21, 2000, which read in part, "It is now clear that you might well give the White House to Bush. As a result, you would set back significantly the social progress to which you have devoted your entire, astonishing career."[24]

When Nader, in a letter to environmentalists, attacked Gore for "his role as broker of environmental voters for corporate cash," and "the prototype for the bankable, Green corporate politician," and what he called a string of broken promises to the environmental movement, Sierra Club president Carl Pope sent an open letter to Nader, dated October 27, 2000, defending Al Gore's environmental record and calling Nader's strategy "irresponsible."[25] He wrote:

You have also broken your word to your followers who signed the petitions that got you on the ballot in many states. You pledged you would not campaign as a spoiler and would avoid the swing states. Your recent campaign rhetoric and campaign schedule make it clear that you have broken this pledge... Please accept that I, and the overwhelming majority of the environmental movement in this country, genuinely believe that your strategy is flawed, dangerous and reckless.[26]

Pope also protested Nader's suggestion that a "bumbling Texas governor would galvanize the environmental community as never before," and his statement that "The Sierra Club doubled its membership under James G. Watt."[27] Wrote Pope in a letter to the New York Times dated November 1, 2000:

Our membership did rise, but Mr. Nader ignores the harmful consequences of the Reagan-Watt tenure. Logging in national forests doubled. Acid rain fell unchecked. Cities were choked with smog. Oil drilling, mining and grazing increased on public lands. A Bush administration promises more drilling and logging, and less oversight of polluters. It would be little solace if our membership grew while our health suffered and our natural resources were plundered.[28]

On October 26, 2000, Eric Alterman wrote in The Nation, "Nader has been campaigning aggressively in Florida, Minnesota, Michigan, Oregon, Washington and Wisconsin. If Gore loses even a few of those states, then Hello, President Bush. And if Bush does win, then Goodbye to so much of what Nader and his followers profess to cherish."[29]

After the election

A study in 2002 by the Progressive Review found no correlation in pre-election polling numbers for Nader when compared to those for Gore. In other words, most of the changes in pre-election polling reflect movement between Bush and Gore rather than Gore and Nader, and they conclude from this that Nader was not responsible for Gore's loss.[30]

Harry G. Levine, in his essay Ralph Nader as Mad Bomber states that Tarek Milleron, Ralph Nader's nephew and advisor, when asked why Nader would not agree to avoid swing states where his chances of getting votes were less, answered, "Because we want to punish the Democrats, we want to hurt them, wound them."[31]

Syndicated columnist Marianne Means said of Nader's 2000 candidacy,

His candidacy was based on the self-serving argument that it would make no difference whether Gore or George W. Bush were elected. This was insane. Nobody, for instance, can imagine Gore picking as the nation's chief law enforcement officer a man of Ashcroft's anti-civil rights, antitrust, anti-abortion and anti-gay record. Or picking Bush's first choice to head the Labor Department, Linda Chavez, who opposes the minimum wage and affirmative action.[32]

Jonathan Chait of the American Prospect said this of Nader's 2000 campaign--

So it particularly damning that Nader fails to clear even this low threshold (Honesty). His public appearances during the campaign, far from brutally honest, were larded with dissembling, prevarication and demagoguery, empty catchphrases and scripted one-liners. Perhaps you think this was an unavoidable response to the constraints of campaign sound-bite journalism. But when given more than 300 pages to explain his case in depth, Nader merely repeats his tired aphorisms.[33]

An analysis conducted by Harvard Professor B.C. Burden in 2005 showed Nader did "play a pivotal role in determining who would become president following the 2000 election", but that:

Contrary to Democrats’ complaints, Nader was not intentionally trying to throw the election. A spoiler strategy would have caused him to focus disproportionately on the most competitive states and markets with the hopes of being a key player in the outcome. There is no evidence that his appearances responded to closeness. He did, apparently, pursue voter support, however, in a quest to receive 5% of the popular vote.[6]

However, Chait notes that Nader did indeed focus on swing states disproportionately during the waning days of the campaign, and by doing so jeopardized his own chances of achieving the 5% of the vote he was aiming for.

There was the debate within the Nader campaign over where to travel in the waning days of the campaign. Some Nader advisers urged him to spend his time in uncontested states such as New York and California. These states – where liberals and leftists could entertain the thought of voting Nader without fear of aiding Bush – offered the richest harvest of potential votes. But, Martin writes, Nader – who emerges from this account as the house radical of his own campaign – insisted on spending the final days of the campaign on a whirlwind tour of battleground states such as Pennsylvania and Florida. In other words, he chose to go where the votes were scarcest, jeopardizing his own chances of winning 5 percent of the vote, which he needed to gain federal funds in 2004.[34]

An analysis and study by Neal Allen and Brian J. Brox titled "The Roots of Third Party Voting" stated that although Nader did affect the outcome of the election by changing the outcome in Florida:

On the whole, however, our analysis of voters who support third party and independent presidential candidates suggests that these voters, in keeping with the history of third party candidacies as vehicles for protest against the two-party system, would have voted for other independent or third party candidates, or would not have voted, if Nader had not been an available alternative to Gore or Bush.[35]

Result

Best states

In order for the Green Party to qualify for federal funds in the next election, Ralph Nader would have needed 5% of the total popular vote. Nader did receive 5% or more of the vote in the following states/districts:[36]

- Alaska: 10.07%

- Vermont: 6.92%

- Massachusetts: 6.42%

- Rhode Island: 6.12%

- Montana: 5.95%

- Hawaii: 5.88%

- Maine: 5.70%

- Colorado: 5.25%

- District of Columbia: 5.24%

- Minnesota: 5.20%

- Oregon: 5.04%

Best counties

- San Miguel County, Colorado: 17.20%

- Missoula County, Montana: 15.03%

- Grand County, Utah: 14.94%

- Mendocino County, California: 14.68%

- Hampshire County, Massachusetts: 14.59%

- Franklin County, Massachusetts: 13.87%

- San Juan County, Colorado: 13.30%

- Pitkin County, Colorado: 12.99%

- Gunnison County, Colorado: 12.81%

- Humboldt County, California: 12.68%

- Boulder County, Colorado: 11.82%

- La Plata County, Colorado: 11.61%

- Windham County, Vermont: 11.52%

- Tompkins County, New York: 11.35%

- Gilpin County, Colorado: 11.20%

- Dukes County, Massachusetts: 11.10%

- San Juan County, Washington: 10.39%

- Travis County, Texas: 10.37%

- Saguache County, Colorado: 10.32%

- Cook County, Minnesota: 10.28%

- Summit County, Colorado: 10.22%

- Douglas County, Kansas: 10.12%

- Santa Cruz County, California: 10.01%

Campaign staff

- Theresa Amato - Campaign manager[37]

- Jim Davis - Campus coordinator for the campaign[38]

- Howie Hawkins - Field Coordinator for Upstate New York

Endorsements

References

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20000815110509/http://votenader.org/press/000221PresAnnounce.html

- ^ "Ballot Access News - August 1, 2000". Web.archive.org. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Ballot Access News - September 1, 2000". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on August 20, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Levine, Harry G. (May 2004).

- ^ a b "Did Ralph Nader Spoil a Gore Presidency? A Ballot-Level Study of Green and Reform Party Voters in the 2000 Presidential Election" (PDF). UCLA. April 24, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Burden, B. C. (September 2005). "Ralph Nader's Campaign Strategy" (PDF). American Politics Research: 673–699.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (July 28, 2004). "The Constituencies: Liberals; From Chicago '68 to Boston, The Left Comes Full Circle". New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Convictions Intact, Nader Soldiers On – New York Times Archived September 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Varadarajan, Tunku (May 31, 2008). "Interview: Ralph Nader". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Moser, Richard (June 6, 2016). "The Myth of the Spoiler: Why the Machine Elites Fear Democracy". CounterPunch.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Don't Fall for It: The Nader Myth and Your 2016 Vote". Truthdig. August 2, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Fisher, Anthony L. (August 3, 2016). "No, Ralph Nader Did Not Hand the 2000 Presidential Election to George W. Bush". Reason (magazine).

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Ballot Access News - August 1, 2000". Web.archive.org. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Ralph Nader Acceptance Statement for Green Party 2000 nomination for President". Ratical.org. June 25, 2000. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Common Dreams Progressive Newswire (July 11, 2001).Green Meeting Will Establish Greens as a National Party. Retrieved 8-28-2009.

- ^ Nelson, Susan.Synthesis/Regeneration 26 (Fall 2001). The G/GPUSA Congress and the ASGP Conference: Authentic Grassroots Democracy vs. Packaged Public Relations. Retrieved 8-28-2009.

- ^ Ralph Nader.Crashing the Party: Taking on the Corporate Government in an Age of Surrender. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2002.

- ^ ave Umhoefer and Dennis Chaptman. "Nader: 'Forked-Tongued' Gore Must Fend For Himself." Milwaukee Journal, November 2, 2000.

- ^ a b Boston Globe (Oct. 2, 2000) republished on CommomDreams.org. Nader 'Super Rally' Draws 12,000 To Boston's FleetCenter

- ^ Van, Tudor. "Ralph Nader - The New York Times". Topics.nytimes.com. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ Independent Candidates' Battle Against the Exclusionary Practices of the Commission on Presidential Debates by Eric B. Hull

- ^ "Dear Conservatives Upset With the Policies of the Bush Administration". Nader for President 2004. Archived from the original on July 2, 2004.

- ^ SeeEditors (October 21, 2000) "The 2000 Campaign; Campaign Briefing." New York Times.

- ^ "Nader Sierra Club Gore Debate". Knowthecandidates.org. June 15, 2001. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Sierra Club Responds To Nader's Environmental Letter". Commondreams.org. October 27, 2000. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Nader Sees a Bright Side to Bush Victory." The New York Times, November 1, p. 29.

- ^ Pope, Carl (November 1, 2000) "Nader's Green Logic (Letter to the Editor).", The New York Times

- ^ "Not One Vote!". Web.archive.org. September 12, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Sam Smith. "Poll Analysis: Nader Not Responsible For Gore'S Loss". Prorev.com. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ [2] [dead link]

- ^ [3] [dead link]

- ^ "Books in Review:". Prospect.org. October 15, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Books in Review: | The American Prospect". Prospect.org. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ Neal Allen; Brian J. Brox. "THE ROOTS OF THIRD PARTY VOTING : The 2000 Nader Campaign in Historical Perspective" (PDF). Tulane.edu. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Presidential Election of 2000, Electoral and Popular Vote Summary". Infoplease.com. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ [4][dead link]

- ^ Chen, David W. (October 15, 2000). "THE 2000 CAMPAIGN: THE GREEN PARTY; In Nader Supporters' Math, Gore Equals Bush". The New York Times.

- ^ "Electrical workers' union backs Nader". CNN. August 31, 2000.

- ^ a b c d "National Endorsements-Organizations". Gwu.edu. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ The Gainesville Iguana. "United Electrical Workers vote to endorse Ralph Nader". Afn.org. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Autoworkers Ride With Gore". CBS News. August 6, 2000.

- ^ Ralph Nader. "Crashing the Party: Taking on the Corporate Government in an Age of Surrender". Books.google.com. p. 191. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m [5][dead link]

- ^ "www.thevoicenews.com". Thevoicenews.com. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ [6][dead link]

- ^ "Nader still guaranteed to stir strong sentiments". Los Angeles Times. March 13, 2004.

- ^ "Greens Nominate Nader for a Serious Run". Commondreams.org. June 26, 2000. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Chen, David W. (October 15, 2000). "THE 2000 CAMPAIGN: THE GREEN PARTY; In Nader Supporters' Math, Gore Equals Bush". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Ayres Jr, B. Drummond (June 4, 2000). "Political Briefing; Lighter Nader Grows Heavier in Polls". The New York Times.

- ^ "Common Dreams News Center". Commonsdreams.org. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c Buck, Molly (October 27, 2000). "Freezerbox Magazine - Ralph Nader Super-Rally at MSG". Freezerbox.com. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ [7][dead link]

- ^ a b c "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Nader 2000 Leader Urge Kerry/Edwards in Swing States". Gwu.edu. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "National Endorsements-Newspapers". Gwu.edu. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Guyette, Curt. "Nader deserves more than votes | Politics & Prejudices | Detroit Metro Times". Metrotimes.com. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "A Green Light for Nader". Village Voice. October 31, 2000. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Endorsements - News". The Austin Chronicle. November 3, 2000. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Ballot Access News - August 1, 2000". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on October 22, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Ballot Access News - September 1, 2000". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on August 20, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ [8][dead link]

- ^ "ISR issue 14 | The Only Real Choice in Election 2000". Isreview.org. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Nader vs. Anybody But Bush: A Debate on Ralph Nader's Candidacy". Democracy Now!. October 26, 2004. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "stdin: [sixties-l] Nader and the 'sixties: 296 academics, et. a". Lists.village.virginia.edu. October 14, 2000. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Crashing the Party: Taking on the Corporate Government in an Age of Surrender> by Ralph Nader

- ^ American social leaders and activists by Neil A. Hamilton

- ^ "Greg Kafoury | Attorney at Kafoury & McDougal". Kafourymcdougal.com. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchives.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Richard Falk. "Christopher Hitchens: A political enigma". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Nader 2000 | News Room". Webarchive.loc.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

External links