The Holocaust in Poland

Map of the Holocaust in occupied Poland during World War II with six extermination camps: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bełżec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibór and Treblinka; as well as remote mass killing sites at Bronna Góra, Ponary, Połonka and others. Marked with the Star of David are selected large Polish cities with the extermination ghettos | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Period | September 1939 – April 1945 |

| Territory | Occupied Poland, also present day western Ukraine and western Belarus among others |

| Major perpetrators | |

| Units | SS-Totenkopfverbände, Einsatzgruppen, Orpo battalions, Trawnikis, BKA, OUN-UPA, TDA, Ypatingasis būrys [1][2][3] |

| Killed | 3,000,000 Polish Jews [4] |

| Survivors | 50,000–120,000[5] |

| Armed resistance | |

| Jewish uprisings | Warsaw, Białystok, Łachwa, Częstochowa, Wilno, Będzin, Mińsk Mazowiecki, Pińsk, Sosnowiec, Mizocz, Birkenau, Treblinka, Sobibór, Poniatowa |

The Holocaust in German-occupied Poland was the last stage of the Nazi "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" (Endlösung der Judenfrage) marked by the construction of death camps on Polish soil in 1941–42. The genocide officially sanctioned and executed by the Third Reich during World War II, collectively known as the Holocaust, took the lives of more than three million Polish Jews. The extermination camps played a central role in the implementation of the German policy of systematic and mostly successful destruction of over 90% of the indigenous Polish-Jewish population of the pre-war Second Polish Republic.[6]

Every arm of the sophisticated German bureaucracy was involved in the killing process, from the Interior Ministry and the Finance Ministry; to German firms and state-run trains used for deportation of Jews.[7][8] German companies bid for the contracts to build the crematoria in concentration camps run by Nazi Germany in the General Government and other parts of occupied Poland and beyond.[6][9]

Throughout the German occupation, at great risk to themselves and their families, many Christian Poles succeeded in rescuing Jews from the Nazis. Grouped by nationality, Polish rescuers represent the biggest number of people who saved Jews during the Holocaust.[5][10] Already recognized by the State of Israel, the Polish Righteous Among the Nations include 7,232 gentiles, more than any other nation.[10] A very small percentage of Polish Jews managed to survive World War II within the German-occupied Poland or successfully escaped east beyond the reach of the Nazis into the territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union,[11] only to be deported to camps in Siberia along with the families of up to 1 million Polish non-Jews.[12][13]

Background

Following the 1939 invasion of Poland in accordance with the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact,[14] Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union partitioned Poland into several occupation zones. Large areas of western Poland were annexed by Germany.[15] The Soviets tricked the Poles into believing that they crossed the border to help Poland fight Germany; and subsequently took over some 51.6% of the territory of Poland with fewer military losses.[16] The entire Kresy macroregion – inhabited by about 13,200,000 people – was annexed by the Soviet Union in the atmosphere of terror surrounding the rigged referendum staged by the secret police and the Red Army.[17] Within months, the Polish Jews in the Soviet-occupied zone who refused to swear an oath of allegiance were deported to Siberia along with the Catholics. Their number is estimated at about 200,000 men, women and children among those who managed to survive in extreme conditions.[18] Both occupying powers were equally hostile to the existence of sovereign Polish state.[19] However, the Soviet rule was short-lived because the terms of the Nazi–Soviet Pact signed earlier in Moscow were broken, when the German army crossed the Soviet occupation zone on June 22, 1941. From 1941 to 1943 all of Poland was under the control of Nazi Germany.[20] The semi-colonial territory of the General Government set up in central and south-eastern Poland took up 39 percent of the occupied area.[21]

The German Nazi extermination policy

There were 3,500,000 Jews in the Polish Second Republic prior to World War II, about 10% of the general population, living predominantly in the cities. Between the German invasion of Poland in 1939, and the end of World War II, over 90% of Polish Jewry perished.[5]

Persecution of the Jews by the German occupation authority began immediately after the invasion, particularly in major urban areas. In the first year and a half, the Nazis confined themselves to stripping the Jews of their valuables and property for profit,[6] herding them into makeshift ghettos and forcing them into slave labor in war-related industries. During this period the Germans ordered Jewish communities to appoint Jewish Councils (Judenräte) to administer the ghettos and to be "responsible in the strictest sense" for carrying out orders. After the German attack in June 1941 on the Soviet positions in eastern Poland, German police battalions (Orpo), SiPo, and special-task Einsatzgruppen operated behind the front lines along with Ukrainian and Lithuanian auxiliaries systematically shooting tens of thousands of men, women and children independently of the army. Massacres were committed in over 30 locations including Tarnopol, Radomyśl, Białystok, as well as provincial capitals of Łuck, Lwów, and Stanisławów among others.[22][23] Gas vans were made available in November 1941.[24] The survivors of mobile killing operations were incarcerated in the newly created ghettos of pure economic exploitation,[21] and starved slowly to death by artificial famine (künstliche Hungersnot) at the whim of German authorities.[25]

At the Wannsee conference near Berlin on January 20, 1942, Dr Josef Bühler urged Reinhard Heydrich to begin the proposed "final solution to the Jewish question". Accordingly, in spring 1942 the Germans began their program of mass murder of the Jewish people by means of poison gas; beginning with the Jewish population of the General Government. Six extermination camps (Auschwitz, Belzec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibór and Treblinka) were established in which the most extreme measures of the Holocaust, the extermination of millions of Jews from Poland and all over Europe, was carried out between 1942 and 1944. The camps were designed and operated by Nazi Germans and there were no Polish guards at any of the camps,[26] despite the sometimes used misnomer Polish death camps. Out of Poland's prewar Jewish population of 3,500,000 only about 50,000–120,000 survived the war on Polish soil.[5]

Ghettos and the extermination program

The plight of Jews in war-torn Poland can be divided into stages defined by the existence of the ghettos. Before their formation,[27] the escape from persecution did not involve extrajudicial punishment by death. Once the ghettos were created however, death by starvation and disease became rampant, alleviated only by smuggling of food and medicine described by Ringelblum as "one of the finest pages in the history between the two peoples".[28] The escape from the ghettos became the only chance for survival once their brutal liquidation began in round-ups for the so-called resettlement trains. The final liquidation of the ghettos across Poland was closely connected with the formation of highly secretive killing centers designed by the SS and built at about the same time by various German companies including I.A. Topf and Sons of Erfurt, and C.H. Kori GmbH.[29][30][31] Civilians were forbidden to approach them and often killed if caught near the train tracks.[32]

Unlike other Nazi concentration camps where prisoners from all across Europe were exploited for the war effort, German death camps – part of secretive Operation Reinhardt – were designed exclusively for the rapid elimination of Polish Jews subsisting in isolation. The camp's German overseers reported directly to Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler in Berlin, who kept control of the extermination program, but who has delegated the work in Poland to SS-Obergruppenführer Odilo Globocnik. The selection of sites, construction of facilities and training of personnel was based on a similar (Action T4) "racial hygiene" program of mass killings developed in Germany.[33][34]

Death camp at Chełmno

The Chełmno extermination camp (German: Kulmhof) was built in 1941 as the first-ever, 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Łódź, following Hitler's launch of Operation Barbarossa. It was a pilot project for the development of the remaining sites. The experiments with engine exhaust gases were finalized by murdering 1,500 Poles at Soldau.[35] The killing method used in Chełmno was based on the clandestine Action T4 program run by the SS before and after the invasion of Poland, in which busloads of unsuspecting hospital patients were gassed in air-tight shower rooms at Bernburg, Hadamar and Sonnenstein.[36] The killing grounds at Chełmno consisted of a vacated manorial estate similar to Sonnenstein, used for undressing (with a truck-loading ramp in the back), as well as a large forest clearing 4.0 kilometres (2.5 mi) northwest of Chełmno, used for mass burial and open-pit cremation of corpses introduced some time later.[37]

All Polish Jews from the Judenfrei district of Wartheland were deported to Chełmno under the guise of "resettlement". At least 145,000 prisoners from the Łódź Ghetto perished at Chełmno in several waves of mass deportations lasting from 1942 to 1944.[38][39] Additional 20,000 foreign Jews and 5,000 Roma were brought in from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia.[40] All victims were killed with the use of mobile gas vans (Sonderwagen) which had exhaust pipes reconfigured, and poisons added to gasoline (see Chełmno Trials for supplementary data). In the final extermination phase their bodies were cremated in open-air for several weeks during Sonderaktion 1005, to remove the evidence of mass murder. The ashes, mixed with crushed bones, were trucked every night to the nearby river in sacks made from blankets. Proper gas chambers and industrial-scale crematoria were constructed elsewhere in occupied Poland.[41][42]

Auschwitz-Birkenau

The Auschwitz concentration camp located 50 kilometers west of Kraków was the largest of the German Nazi extermination centers. Auschwitz was fitted with the first five permanent gas chambers at Birkenau, beginning in March 1942, and from June 1943, with four additional large gassing-rooms.[43] The extermination of Jews with Zyklon B as the killing agent,[44] began in July 1942 following the ruthless "selection process" at the Judenrampe. Only about 10 percent of the transports organized by the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) were registered and assigned to barracks at Auschwitz-Birkenau.[45] Overwhelming majority of prisoners delivered by an average of 1.5 Holocaust trains per day,[46] were sent directly to the gas chambers.[47]

By early 1943 Birkenau was a killing factory with four crematoria working around the clock. Up to 6,000 people were gassed and cremated there each day.[48] Auschwitz II extermination program resulted in the death of 1.3 to 1.5 million people.[49] Over 1.1 million of them were Jews from across Europe including 200,000 children.[47][50] Among the registered 400,000 victims (less than one-third of the total Auschwitz arrivals) were 140,000–150,000 non-Jewish Poles, 23,000 Gypsies, 15,000 Soviet POWs and 25,000 others,[49][51] on top of 200,000 Jews from Poland, delivered aboard cattle trains from liquidated ghettos and transit camps,[52] beginning with Bytom (February 15, 1942), Kraków (March 13, 1943),[53] Sosnowiec (June–August 1943),[54] and several dozen other metropolitan cities and towns,[55] including the last ghetto left standing in occupied Poland, liquidated in August 1944 at Łódź (Litzmannstadt).[56] Auschwitz-Birkenau gas chambers and crematoria were blown up on November 25, 1944 in an attempt to destroy the evidence of mass killings, by the orders of SS chief Heinrich Himmler.[57]

Treblinka

Designed exclusively for the implementation of the Final Solution, the Treblinka extermination camp was one of only three such facilities in existence; the other two were Bełżec and Sobibór. All of them were situated in wooded areas away from population centres and linked to the Polish rail system by a branch line. They had transferable SS staff.[58] There was a railway platform constructed alongside the tracks, surrounded by an 2.5 m (8 ft) high barbed-wire fencing. Large barracks were built for storing belongings of disembarking victims. One was disguised as a railway station complete with a fake wooden clock and signage to prevent new arrivals from realizing their fate.[59] Passports and money were collected for "safekeeping" at a cashier's booth set up by the Road to Heaven; it was a fenced-off path leading into the gas chambers disguised as showers. Directly behind were the burial pits dug with a crawler excavator.[60]

Located 80 kilometres (50 mi) northeast of Warsaw,[61] Treblinka became operational on July 24, 1942 after three months of forced labour construction by expellees from Germany.[62] The shipping of Jews from the Polish capital – plan known as the Großaktion Warschau – began immediately.[63][64][65] During the two months of summer 1942, about 254,000 Warsaw Ghetto inmates were exterminated at Treblinka (or at least 300,000 by different accounts).[66] On arrival, disrobed men followed by women and children were forced into double-wall chambers and gassed in batches of 200 with the use of exhaust fumes generated by a tank engine.[67][68][69] The gas chambers, rebuilt of brick, and expanded in August–September 1942, were able to kill 12,000 to 15,000 victims every day,[70] with the maximum capacity of 22,000 executions in twenty-four hours.[71] The dead were initially buried in large mass graves, but the stench from the decomposing bodies could be smelled up to ten kilometers away. As a result, later, the Nazis began burning the bodies on open-air grids made of concrete pillars and railway tracks.[72] The number of people killed at Treblinka in about a year, ranges from 800,000 to 1,200,000 with no exact figures available.[73][74] The camp was officially closed by Globocnik on October 19, 1943 soon after the Treblinka prisoner uprising,[75] with the murderous Operation Reinhard nearly completed.[73]

Bełżec

The Bełżec extermination camp created near the railroad station of Bełżec in the Lublin District, began operating officially on March 17, 1942 with three temporary gas chambers later replaced with six made of brick and mortar,[76] enabling the facility to handle over 1,000 victims at one time. At least 434,500 Jews were exterminated there. The lack of verified survivors however, makes this camp much less known.[77] The bodies of the dead, buried in mass graves, swelled in the heat as a result of putrefaction making the earth split, which was resolved with the introduction of crematoria pits in October 1942.[78]

Obersturmführer Kurt Gerstein from Waffen-SS, supplying Zyklon B from Degesch during the Holocaust,[79] wrote after the war in his Gerstein Report for the Allies that on August 17, 1942 at Belzec, he had witnessed the arrival of 45 wagons with 6,700 prisoners of whom 1,450 were already dead inside.[80] That train came with the Jewish people of the Lwów Ghetto,[81] less than a hundred kilometers away.[82] The last shipment of Jews (including those who had already died in transit) arrived in Bełżec in December 1942.[83] The burning of exhumed corpses continued until March.[84] The remaining 500 Sonderkommando prisoners who dismantled the camp, and who bore witness to the extermination process,[85] were murdered at the nearby Sobibór extermination camp in the following months.[86][87]

Sobibór

The Sobibór extermination camp, disguised as a railway transit camp not far from Lublin, began mass gassing operations in May 1942.[88][89] As in other extermination centers, the Jews, taken off the Holocaust trains arriving from liquidated ghettos and transit camps (Izbica, Końskowola) were met by an SS-man dressed in a medical coat. Oberscharführer Hermann Michel gave the command for prisoners' "disinfection". [90]

New arrivals were forced to split into groups, hand over their valuables, and disrobe inside a walled-off courtyard for a bath. Women had their hair cut off by the Sonderkommando barbers. Once undressed, the Jews were led down a narrow path to the gas chambers which were disguised as showers. Carbon monoxide gas was released from the exhaust pipes of a gasoline engine removed from a Red Army tank.[91] Their bodies were taken out and burned in open pits over iron grids partly fueled by human body-fat. Their remains were dumped onto seven "ash mountains". The total number of Polish Jews murdered at Sobibór is estimated at a minimum of 250,000. [92] Heinrich Himmler ordered the camp dismantled following a prisoner revolt on October 14, 1943; one of only two successful uprisings by Jewish Sonderkommando inmates in a Nazi extermination camp, with 300 escapees (most of them were recaptured by the SS and killed).[93][94]

Lublin-Majdanek

The Majdanek forced labor camp located on the outskirts of Lublin like Sobibór and closed during typhus epidemic, was reopened in March 1942 for Operation Reinhard, first, as a storage depot for valuables stolen from the victims of gassing at the killing centers of Belzec, Sobibór, and Treblinka,[95] It became a place of extermination of large Jewish populations from south-eastern Poland (Kraków, Lwów, Zamość, Warsaw) after the gas chambers were constructed in late 1942.[96] The gassing of Polish Jews was performed in plain view of other inmates, without as much as a fence around the killing facilities.[97] According to witness's testimony, "to drown the cries of the dying, tractor engines were run near the gas chambers" before they took the dead away to the crematorium. Majdanek was the site of death of 59,000 Polish Jews (from among its 79,000 victims).[98][99] By the end of Operation Harvest Festival in early November 1943 (the single largest German massacre of Jews during the entire war),[100] Majdanek had only 71 Jews left.[101]

The "resettlement"

The scale of the Final Solution would not have been possible without mass transport. The extermination of Polish Jews depended on the railways as much as on the secluded killing centres. The Holocaust trains sped up the scale and duration over which the extermination took place, and, the enclosed nature of cattle wagons also reduced the number of troops required to guard them. Rail shipments allowed the Nazi Germans to build and operate bigger and more efficient death camps and, at the same time, openly lie to the world – and to their victims – about a "resettlement" program.[7][102] In one telephone conversation Heinrich Himmler informed Martin Bormann about the Jews already exterminated in Poland, to which Bormann screamed in response: "They were not exterminated, only evacuated, evacuated, evacuated!"[46]

Unspecified number of deportees died in transit during Operation Reinhard from suffocation and thirst. No food or water was supplied. The Güterwagen boxcars were only fitted with a bucket latrine. A small barred window provided little ventilation, which oftentimes resulted in multiple deaths.[103] Millions of people were transported in such trainsets to the extermination camps under the direction of the German Ministry of Transport, and tracked by an IBM subsidiary, until the official date of closing of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex in December 1944.[104][105]

Death factories were just one of a number of ways of mass extermination. In the Eastern regions conquered by Germany during Operation Barbarossa, the SS had recruited collaborationist auxiliary police (Hiwis) from among Soviet nationals.[3][106] They were known as "Trawniki men" (German: Trawnikimänner) for deployment in all major killing sites of Operation Reinhard (their primary purpose of training). Trawnikis took an active role in the executions of Jews at Belzec, Sobibór, Treblinka II, during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (on three occasions, see Stroop Report), Częstochowa, Lublin, Lwów, Radom, Kraków, Białystok (twice), Majdanek, Auschwitz, the Trawniki concentration camp itself,[3] and the remaining subcamps of KL Lublin/Majdanek camp complex including Poniatowa, Budzyń, Kraśnik, Puławy, Lipowa, and also during massacres in Łomazy, Międzyrzec, Łuków, Radzyń, Parczew, Końskowola, Komarówka and all other locations, augmented by members of the SS, as well as the reserve police battalions from Orpo (each, responsible for annihilation of thousands of Jews). The Order Police performed liquidations of the Jewish ghettos in German-occupied Poland, filling boxcars with Jews and shooting people unable to move or attempting to flee, while the Trawnikis conducted large-scale massacres in those places.[100][107] Mass executions of Jews (as in Szebnie) was part of regular training of the auxiliary Ukrainian 14th Waffen SS Division soldiers from the SS Heidelager troop-training base in Pustków in south-eastern Poland.[108][109] In the north-east, the "Poachers' Brigade" of Oskar Dirlewanger trained Belarusian Home Guard in murder expeditions.[110]

Poles and the Jews

The relations between Poles and Jews during World War II present one of the sharpest paradoxes of the Holocaust. Only 10 percent of Poland's Jews survived the genocide, less than in any other country; and yet, Poland accounts for the majority of rescuers with the title of 'Righteous Among the Nations', i.e. people who risked their lives to save Jews. The Poles honored by Yad Vashem are a fraction of the true number of deserving individuals and: "so far represent only the tip of the iceberg," according to Paulsson.[111] The nature of this paradox was debated by historians on both sides for more than fifty years often with preconceived notions and selective evidence.[111]

Many Jews, persecuted by the Germans, received help from the Poles; help, ranging from major acts of heroism, to minor acts of kindness involving hundreds of thousands of helpers acting often anonymously. This rescue effort occurred even though (since October 1941) ethnic Poles themselves were the subject to capital punishment at the hands of the Nazis if found offering any kind of help to a person of Jewish faith or origin (Poland was the only country in German-occupied Europe in which such a death penalty was applied).[111][112]

On November 10, 1941, the death penalty was expanded by Hans Frank to apply to Poles who helped Jews "in any way: by taking them in for the night, giving them a lift in a vehicle of any kind" or "feed[ing] runaway Jews or sell[ing] them foodstuffs." The law was made public by posters distributed in all major cities. Capital punishment of entire families, for aiding Jews, was the most draconian such Nazi practice against any nation in occupied Europe.[113][114][115] In total, some 30,000 Poles were executed by the Nazis for hiding them.[116][117] Over 700 Polish Righteous among the Nations received their award posthumously, having been murdered by the Germans for aiding or sheltering their Jewish neighbors.[118] Many of the Polish Righteous awarded by Yad Vashem came from the capital. In his work on the Jews of Warsaw, Gunnar S. Paulsson has demonstrated that despite the much harsher conditions, Polish citizens of Warsaw managed to support and hide the same percentage of Jews as did the citizens of cities in reportedly safer countries of Western Europe.[119]

Difficulties in rescue attempts

Toward the end of the ghetto liquidation period, the largest number of Jews managed to escape to the 'Aryan' side,[111] and to survive with the assistance of their Polish neighbors. In general, during the German occupation most Poles were engaged in a desperate struggle for survival. They were in no position to oppose or impede the German extermination of the Jews. There were however many Poles risking death to hide Jewish families and in various ways assist the Jews on compassionate grounds. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands, or even a million Poles, aided their Jewish neighbors.[5][120] The number of Polish Jews kept in hiding by non-Jewish Poles was around 450,000.[5] To put these numbers in perspective, three and a half million Jews lived in Poland before the war, out of a total population in Poland of about 27 million people.[5]

Polish Jews were a 'visible minority' by modern standards, distinguishable by language, behavior and appearance.[111] For hundreds of thousands of them the Polish language was barely familiar.[121] According to Polish census of 1931 only 12% of Jews listed Polish as their first language while 79% of them declared Yiddish and the remaining 9% Hebrew as the mother-tongue.[122] By contrast, the overwhelming majority of German-born Jews of this period spoke German as their first language. The presence of such large non-Christian, mostly non acculturated minority in prewar Poland,[123] was a source of competitive tension, and periodically of violence between Poles and Jews. Here is where the temptation to jump to conclusions with regard to Holocaust rescue comes into play according to Gunnar Paulsson.[111] As elsewhere in Europe during the interwar period, there was both official and popular anti-Semitism in Poland, at times encouraged by the Catholic Church and by some political parties (particularly the right-wing endecja faction), but not directly by the government. There were also political forces in Poland which opposed anti-Semitism, particularly centered around the tolerant Polish dictator, Józef Piłsudski. In the late 1930s after Piłsudski's death, reactionary and anti-Semitic elements gained ground.[124] Nonetheless, "leaving aside acts of war and Nazi perfidy, a Jew's chances of survival in hiding were no worse in Warsaw, at any rate, than in the Netherlands,"[111] once the Holocaust began.

Poland was occupied by the Nazis from 1939 to 1945 and no Polish collaboration government was ever formed during that period.[125] The Polish Government in Exile was the first (in November 1942)[126] to reveal the existence of Nazi-run concentration camps and the systematic extermination of the Jews by the Germans, reported by its courier Jan Karski and the activities of Witold Pilecki, a member of Armia Krajowa who volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz in order to organize a resistance movement inside the camp itself. In September 1942 the Provisional Committee for Aid to Jews (Tymczasowy Komitet Pomocy Żydom) was founded with assistance from the Underground State and on the initiative of Zofia Kossak-Szczucka. This body later became the Council for Aid to Jews (Rada Pomocy Żydom), known by the code-name Żegota. It is not known how many Jews were helped by Żegota, but at one point in 1943 it had 2,500 Jewish children under its care in Warsaw alone. Żegota was granted nearly 29 million zlotys (over $5 million) since 1942 for the relief payments to thousands of extended Jewish families in Poland.[127] The government in exile also provided special assistance – funds, arms and other supplies – to Jewish resistance organizations (like ŻOB and ŻZW).[128] The Polish Underground State strongly opposed collaboration in anti-Jewish persecutions and threatened with death the informers against them, on behalf of the Polish military tribunals of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa).[129]

In some cases, the Germans across Europe were able to exploit the local populace's anti-Semitism, and Poland was no exception. In occupied Poland death was a standard punishment for a Polish person with family and neighbors,[130] for any help given to Jews, one of the many coercive techniques used by Germans.[113] Some persons betrayed hidden Jews to the Germans, others made money as extortionists (szmalcownik), blackmailing Jews in hiding and Poles who protected them.[131] Estimates of the number of Polish collaborators vary. The lower estimate of seven thousand is based primarily on the sentences of the Special Courts of the Polish Underground State, sentencing individuals for treason to the nation; the highest estimate of about one million,[132] includes all Polish citizens who in some way contributed to the German activities, such as: low-ranking Polish bureaucrats employed in German administration, members of the Blue Police, construction workers, slave laborers in German-run factories and farms and similar others (notably the highest figure originates from a single statistical table of outdated scholarship with a very thin source base).[133] Relatively little active collaboration by individual Poles – with any aspect of the German presence in Poland – took place. All Nazi propaganda efforts to recruit Poles in either labor or auxiliary roles were met with almost no interest, due to the everyday reality of German occupation. The non-German auxiliary workers in the extermination camps, for example, were mostly Ukrainians and Balts. John Connelly quoted a Polish historian (Leszek Gondek) calling the phenomenon of Polish collaboration "marginal" and stated "only relatively small percentage of Polish population engaged in activities that may be described as collaboration when seen against the backdrop of European and world history".[133] The unique Polish Underground State considered szmalcownictwo an act of collaboration with the enemy, and with the aid of its military arm, the Armia Krajowa, punished it with the judicatory death sentence. Up to 10,000 Poles were tried by Polish underground courts for assisting the enemy, and 2,500 were executed.[132]

Role of national minorities

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Jews and Judaism in Poland |

|---|

| Historical Timeline • List of Jews |

|

|

The Republic of Poland was a multicultural country before World War Two, with almost a third of its population originating from the minority groups: 13.9% Ukrainians; 10% Jews; 3.1% Belarusians; 2.3% Germans and 3.4% percent Czechs, Lithuanians and Russians. The first spontaneous flight of about 500,000 refugees from the Soviet Union occurred during the reconstitution of sovereign Poland. In the second wave, between November 1919 and June 1924 some 1,200,000 people left the territory of the USSR for Poland. It is estimated that some 460,000 of them spoke Polish as the first language.[134] After the invasion, in May 1940 hundreds of ethnically German men joined the Nazi Sonderdienst formations,[135] launched by Gauleiter Hans Frank stationing in occupied Kraków.[136] The existence of Sonderdienst constituted a grave danger to the Catholic Poles who attempted to help ghettoised Jews in the cities which had a sizable German and pro-German minorities, as in the case of the Izbica Ghetto or Łuck and the Mińsk Mazowiecki Ghettos among numerous other locations. Anti-Semitic attitudes were particularly visible in the eastern provinces which had been earlier occupied by the Russians following the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland. Local population had witnessed the repressions against their own compatriots, and mass deportation of up to 1 million ethnic Poles to Siberia,[13][137] conducted by the Soviet security apparatus, with some of the local Jews collaborating with them. Others assumed that, driven by vengeance, Jewish Communists had been prominent in betraying the ethnically Polish or other victims.[138][139]

A number of German-inspired massacres were carried out in that region with the active participation of indigenous people. The guidelines for such massacres were formulated by Reinhard Heydrich,[140] who ordered his officers to induce anti-Jewish pogroms on territories newly occupied by the German forces.[141][142] In the most infamous series of Lviv pogroms committed by the Ukrainian militants in the eastern city of Lwów (now, Ukraine), some 6,000 Polish Jews were murdered in the streets between June 30 and July 29, 1941 on top of 3,000 arrests and mass shootings by Einsatzgruppe C.[143][144] The Ukrainian People's Militia formed by OUN with the blessings of the SS spread terror to other locations throughout Kresy.[145] In Tarnopol 600 Jewish men were killed by them,[146] some of whom were decapitated,[147] although the SS shot three times as many Jews.[146] In Stanisławów – another provincial capital in the Kresy macroregion – the single largest massacre of Polish Jews prior to Aktion Reinhardt was perpetrated hand in glove by Orpo, SiPo and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police brought in from Lwów on 12 October 1941; tables with sandwiches and bottles of vodka had been set up about the cemetery for shooters who needed to rest from the deafening noise of gunfire; 12,000 Jews were murdered before nightfall.[148] A total of 31 deadly pogroms were carried out throughout the region in conjunction with Belarusian, Lithuanian and Ukrainian Schuma.[149] Further north-west, during the massacre in Jedwabne, over 300 Jews died (Institute of National Remembrance's Final Findings),[150] burned alive in a barn set on fire by a group of Polish men in the presence of German Ordnungspolizei. The circumstances surrounding the events in Jedwabne are still debated, and include the ominous presence of the Einsatzgruppe Zichenau-Schroettersburg under SS-Obersturmführer Hermann Schaper deployed in Bezirk Bialystok,[151][152] as well as German Nazi pressure, anti-Semitism, but also resentment over Jewish cooperation with the Soviet invaders during the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 as well as the alleged Jewish participation in anti-Polish terror following Soviet 1939 invasion of Kresy in accordance with the Nazi-Soviet Pact.[153]

Some members of ultra-nationalist National Armed Forces (NSZ, or Narodowe Siły Zbrojne),[154][155] participated in executions of Jews during wartime, according to Stefan Korboński.[156] Other NSZ units rendered assistance to them and included Jews in their ranks as well as Polish Righteous Among the Nations.[157] The NSZ Holy Cross Brigade rescued 280 Jewish women among some 1,000 persons from the concentration camp in Holýšov. A Jewish partisan from NSZ, Feliks Parry, suggested that most of them "didn't have the slightest notion of the ideological underpinnings of their organization" and didn't care, focused only on resisting the Nazis.[158] In postwar Poland, the communist secret police routinely tortured the NSZ insurgents in order to force them to confess to killing Jews among other alleged crimes. This was most notably the case with the 1946 trial of 23 officers of the NSZ in Lublin. The torture of political prisoners by the Ministry of Public Security did not stop automatically when the interrogations were concluded. Physical torture was also ordered if they retracted in court their confessions of "killing Jews".[159]

In 1946, over a year after the end of the war, 42 Jews were killed in the Kielce pogrom, prompting Gen. Spychalski of PWP to sign a legislative decree allowing the remaining survivors to leave Poland without visas or exit permits.[160] Poland was the only Eastern Bloc country to do so upon the conclusion of World War II.[161] Consequently, the Jewish emigration from Poland increased dramatically.[162] Britain demanded from Poland (among others) to halt the Jewish exodus, but their pressure was largely unsuccessful.[163] The massacre in Kielce was condemned by a public announcement sent by the diocese in Kielce to all churches. The letter denounced the pogrom and "stressed that the most important Catholic values were the love of fellow human beings and respect for human life. It also alluded to the demoralizing effect of anti-Jewish violence, since the crime was committed in the presence of youth and children." Priests read it without comments during Mass, "[h]inting that the pogrom might have in fact been a political provocation."[164][165]

Rate of survival

The exact number of Holocaust survivors is unknown. About 300,000 Polish Jews escaped to the Soviet-occupied zone soon after the war started, where many of them perished at the hands of OUN-UPA, TDA and Ypatingasis būrys during Massacres of Poles in Volhynia, the Holocaust in Lithuania (see Ponary massacre), and Belarus,[1][2] but most Polish Jews in the Generalgouvernement stayed put. Prior to the mass deportations, there was no proven necessity to leave familiar places. When the ghettos were closed from the outside, smuggling of food kept most of the inhabitants alive. Escape into clandestine existence on the "Aryan" side was attempted by some 100,000 Jews, and, contrary to popular misconceptions, the risk of them being turned in by the Poles was very small.[111]

The question regarding the Jewish real chances of survival once the Holocaust began continues to draw attention of historians.[111] For one, the Germans made it extremely difficult to escape the ghettos just before "resettlement" to the death camps. All passes were cancelled, walls rebuilt containing fewer gates, with policemen replaced by SS-men. Some victims already deported to Treblinka were forced to write dictated letters back home, stating that they were safe. Around 3,000 others fell into the German Hotel Polski trap. Many ghettoized Jews did not believe what was going on until the very end, because the actual outcome seemed unthinkable at the time.[111] David J. Landau suggested also that the weak Jewish leadership might have played a role.[166] Likewise, Israel Gutman proposed that the Polish Underground might have attacked the camps and blown up the railway tracks leading to them, but as noted by Paulsson, such ideas are a product of hindsight.[111]

It is estimated that about 350,000 Polish Jews survived the Holocaust. Some 230,000 of them survived in the Soviet territory,[167] including eastern half of Poland annexed after the 1939 invasion. Soon after the war ended, some 180,000 to 200,000 Jews took advantage of the repatriation agreement meant to ratify the new borders between Poland and the USSR. The number of Jews in the country changed dramatically, with many Jews passing through on their way to the West. Poland was the only Eastern Bloc country to allow free Jewish aliyah to Mandate Palestine,[168] with Stalin's vexed approval,[169] seeking to undermine British influence in the Middle East. In January 1946, there were 86,000 survivors registered at Central Committee of Polish Jews (CKŻP). By the end of summer, the number had risen to about 205,000–210,000 (with 240,000 registrations and over 30,000 duplicates). Most refugees crossing the new borders left Poland without Western visas or Polish exit permits.[161] Uninterrupted traffic across the Polish borders intensified.[169][170] By the spring of 1947 only 90,000 Jews remained in Poland.[171][172][173]

Gunnar S. Paulsson estimated that 30,000 Jews survived in the labor camps and up to 50,000 in the forests and among soldiers who returned with the pro-Soviet Polish "Berling army" formed by Stalin ahead of his advance into Germany. The number of Jews who successfully hid on the "Aryan" side individually could be as high as 50,000 according to Paulsson's estimates. Many did not register themselves after the war, as was the case with Jewish children hidden by non-Jewish Poles and the Church.[111] The survival rate among the ghetto escapees was relatively high given the severity of German measures designed to prevent this occurrence, and by far, these individuals were the most successful.[111][174]

Holocaust memorials and commemoration

There is a large number of memorials in Poland dedicated to the Holocaust remembrance. Major museums include the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum with 1.4 million visitors per year, and the nearly-completed Museum of the History of the Polish Jews in Warsaw. Since 1988, an annual international event commemorating the Holocaust: March of the Living, takes place in April at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp complex on the Holocaust Remembrance Day, with the total attendance exceeding 150,000 youth from all over the world.[175]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b Timothy Snyder. (2004) The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press: pg. 162

- ^ a b Józef Turowski, with Władysław Siemaszko, Zbrodnie nacjonalistów ukraińskich dokonane na ludności polskiej na Wołyniu 1939–1945, Warsaw: Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce – Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Środowisko Żołnierzy 27 Wołyńskiej Dywizji Armii Krajowej w Warszawie ([Crimes Perpetrated Against the Polish Population of Volhynia by the Ukrainian Nationalists, 1939–1945, published by the Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help) – Institute of National Remembrance, and Association of Soldiers of the 27th Volhynian Division of the Home Army; Warsaw, 1990.

- ^ a b c Holocaust Encyclopedia. "Trawniki" (permission granted to be reused, in whole or in part, on Wikipedia; OTRS ticket no. 2007071910012533). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

Text from USHMM has been released under the GFDL.

- ^ Anti-Defamation League (1997). "Estimated Number of Jews Killed". The "Final Solution". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lukas 1989, pp. 5, 13, 111, 201; see also Lukas 2001, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Berenbaum, Michael (1993). The World Must Know. Contributors: Arnold Kramer, USHMM. Little Brown / USHMM. ISBN 978-0-316-09135-0.

Second ed. (2006) USHMM / Johns Hopkins Univ Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-8358-3, p. 140. - ^ a b Aish HaTorah, Jerusalem, Holocaust: The Trains Internet Archive.

- ^ Simone Gigliotti (2009). "Resettlement". The Train Journey: Transit, Captivity, and Witnessing in the Holocaust. Berghahn Books. p. 55. ISBN 1-84545-927-X. Retrieved September 2015.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ American Jewish Committee. (2005-01-30). "Statement on Poland and the Auschwitz Commemoration." Press release.

- ^ a b Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Righteous Among the Nations - per Country & Ethnic Origin January 1, 2009. Statistics

- ^ Piotrowski 1998, Preface.

- ^ Nora Levin (1990). Annexed Territories. NYU Press. p. 347. ISBN 0-8147-5051-6. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami". Polska 1939–1945. Institute of National Remembrance. 2009. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2015 – via Internet Archive.

Projekt "Indeks represjonowanych" doprowadził do ustalenia liczby ok. 320 tys. osób deportowanych w latach 1940–1941 z Kresów Wschodnich; nadal jednak liczba ta jest podważana przez część historyków, piszących o 700 tys. - 1 mln deportowanych.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kirsten Sellars (28 February 2013). 'Crimes Against Peace' and International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-107-02884-5.

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt (2011), Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950) (PDF), Polish Academy of Sciences, Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization, Monographies; 12, pp. 27–29; via Internet Archive.

- ^ Eberhardt 2011, page 25.

- ^ Bernd Wegner (1997), From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939–1941. Berghahn Books. p. 74. ISBN 1-57181-882-0.

- ^ Piet Buwalda (1997), They Did Not Dwell Alone: Jewish Emigration from the Soviet Union, 1967–1990. Woodrow Wilson Center Press, ISBN 0-8018-5616-7.

- ^ Judith Olsak-Glass, Review of Piotrowski's Poland's Holocaust in Sarmatian Review, January 1999.

- ^ Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis. M.E. Sharpe. 2003. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b Paczkowski, Andrzej (2003). The Spring Will Be Ours: Poland and the Poles from Occupation to Freedom (Google Books). Translated by Jane Cave. Penn State Press. pp. 54, 55–58. ISBN 0-271-02308-2.

Further Reading: "Einsatzgruppen", Holocaust Encyclopedia.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Piotrowski 1998, p. 209 - Collaboration.

- ^ Ronald Headland (1992), Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 125–126. ISBN 0-8386-3418-4.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (2002), Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. New York: Vintage Books, pp. 243, 255. ISBN 0-307-42680-7.

- ^ Christopher R. Browning (2007). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939-March 1942. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 121–130. ISBN 0-8032-0392-6. Retrieved 7 April 2015 – via Google Book, preview.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Robert D. Cherry, Annamaria Orla-Bukowska, Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future, Rowman & Littlefield 2007, ISBN 0-7425-4666-7; re: Hilfswilliger Trawnikis.

- ^ Yisrael Gutman (1989). The First Months of the Nazi Occupation. Indiana University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-253-20511-5. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Emmanuel Ringelblum, Polish-Jewish Relations, p.86.

- ^ Dwork, Deborah and Robert Jan Van Pelt,The Construction of Crematoria at Auschwitz W.W. Norton & Co., 1996.

- ^ University of Minnesota, Majdanek Death Camp

- ^ Cecil Adams, Did Krups, Braun, and Mercedes-Benz make Nazi concentration camp ovens?

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik 2011, p. 405.

- ^ Gitta Sereny, Into That Darkness, Pimlico 1974, 48

- ^ Robert Jay Lifton, The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide, Basic Books 1986, 64

- ^ The Simon Wiesenthal Center (1997), "Responses to Revisionist Arguments" (5); Henry Friedlander (1995), "From Euthanasia to the Final Solution", pp. 18–21 in PDF; International Tracing Service (1949), "Brief Chronology Of the Konzentrationslager System", War Relics, 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Breggin, Peter (1993). "Psychiatry's role in the Holocaust". International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 4 (2): 133–148. doi:10.3233/JRS-1993-4204. PMID 23511221.

- ^ Montague, Patrick (2012), Chełmno and the Holocaust: The History of Hitler's First Death Camp (Google Books), Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-3527-7, retrieved June 14, 2013

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia (2015). "The Jews of Lodz". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Michal Latosinski (2015). "Litzmannstadt Ghetto, Lodz". Traces of the Litzmannstadt Getto. A Guide to the Past: Introduction. Litzmannstadt Ghetto homepage. ISBN 83-7415-000-9. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Shirley Rotbein Flaum, Roni Seibel Liebowitz (2007). "Lodz Ghetto Deportations and Statistics". Sources: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Baranowski, Dobroszycki, Wiesenthal, Yad Vashem Timeline. Łódź ShtetLinks · JewishGen. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ JTA (January 22, 1963). "Jewish Survivors of Chelmno Camp Testify at Trial of Guards". Internet Archive. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fluchschrift (2013). "01.11.1941. Errichtung des ersten Vernichtungslagers in Chelmno". Heiner Lichtenstein, Daten aus der Zeitgeschichte, in: Tribüne Nr. 179/2006. Fluchschrift - Deutsche Verbrechen. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ Institut Fuer Zeitgeschicthe (Institute for Contemporary History), 1992. "Gassing Victims in the Holocaust: Background & Overview". Extermination camps in occupied Poland. Munich, Germany: Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum (2008), SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Fritsch "testing" the gas. (Internet Archive: The 64th Anniversary of the Opening of the Auschwitz Camp) Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Poland (Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu).

- ^ Vincent Châtel & Chuck Ferree (2006). "Auschwitz-Birkenau Death Factory". The Forgotten Camps. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ a b Hedi Enghelberg (2013). The trains of the Holocaust. Kindle Edition. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-60585-123-5.

Book excerpts from Enghelberg.com.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ a b Memorial and Museum (2015). "Auschwitz as a center for the extermination of the Jews" (Countries of origin, Selection in the camp, Treatment). Jews in Auschwitz. Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and State Museum. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia (20 June 2014). "Gassing Operations". The means of mass murder at Auschwitz. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b Franciszek Piper (2015). "Number of deportees by ethnicity". Ilu ludzi zginęło w KL Auschwitz. Liczba ofiar w świetle źródeł i badań, Oświęcim 1992, tables 14–27. Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and State Museum. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Laurence Rees. Auschwitz: A New History. 2005, Public Affairs, ISBN 1-58648-303-X, p. 168–169

- ^ Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation (2015). "The Number and Origins of the Victims". How many people were registered as prisoners in Auschwitz?. History of KL Auschwitz. (Report). Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

{{cite report}}: External link in|sectionurl=|sectionurl=ignored (|section-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Deborah Dwork, Robert Jan van Pelt (1997), Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present, Norton Paperback edition, ISBN 0-393-31684-X, p. 336–337.

- ^ Pressac, Jean-Claude; Van Pelt, Robert-Jan (1994). The Machinery of Mass Murder at Auschwitz. Indiana University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-253-20884-X.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Book of Sosnowiec and the Surrounding Region in Zaglembie".

- ^ The statistical data compiled on the basis of "Glossary of 2,077 Jewish towns in Poland" by Virtual Shtetl Museum of the History of the Polish Jews, as well as "Getta Żydowskie" by Gedeon, and "Ghetto List" by Michael Peters. Comparative range. Accessed March 14, 2015.

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library, Overview of the Ghetto's history

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum - Online Exhibition: Give Me Your Children: Voices from the Lodz Ghetto

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak (1999) [1987]. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0-253-21305-1.

- ^ Testimony of Alexsandr Yeger at the Nizkor Project

- ^ Smith, Mark S. (2010). Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling (Google Books preview). The History Press. pp. 103–107. ISBN 978-0-7524-5618-8. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

See Smith's book excerpts at: Hershl Sperling: Personal Testimony by David Adams, and the book summary at Last victim of Treblinka by Tony Rennell.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote=|ref=harv(help) - ^ fr and Weaver, Helen (translator). Treblinka (Simon & Schuster, 1967).

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik 2011, chapt. 3:1, p. 77.

- ^ "Aktion Reinhard" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies. See: "Aktion Reinhard" named after Reinhard Heydrich, the main organizer of the "Final Solution"; also, Treblinka, 50 miles northeast of Warsaw, set up June/July 1942.

- ^ Barbara Engelking-Boni; Warsaw Ghetto Internet Database hosted by Polish Center for Holocaust Research. The Fund for support of Jewish Institutions or Projects, 2006. Template:Pl icon Template:En icon

- ^ Barbara Engelking-Boni, Warsaw Ghetto Calendar of Events: July 1942 Timeline. See: 22 July 1942 — the beginning of the great deportation action in the Warsaw ghetto; transports leave from Umschlagplatz for Treblinka. Publisher: Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów IFiS PAN, Warsaw Ghetto Internet Database 2006.

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Last Updated: May 20, 2008.

- ^ McVay, Kenneth (1984). "The Construction of the Treblinka Extermination Camp". Yad Vashem Studies, XVI. Jewish Virtual Library.org. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Court of Assizes in Düsseldorf, Germany. Excerpts From Judgments (Urteilsbegründung). AZ-LG Düsseldorf: II 931638.

- ^ "Operation Reinhard: Treblinka Deportations" The Nizkor Project, 1991–2008

- ^ Ainsztein, Reuben (2008) [1974]. Jewish Resistance in Nazi-Occupied Eastern Europe (Google Books snipet view). University of Michigan (reprint). p. 917. ISBN 0-236-15490-7. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ David E. Sumler, A history of Europe in the twentieth century. Dorsey Press, ISBN 0-256-01421-3.

- ^ Klee, Ernst., Dressen, W., Riess, V. The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. ISBN 1-56852-133-2.

- ^ a b Kopówka, Edward; Rytel-Andrianik, Paweł (2011), "Treblinka II – Obóz zagłady" (PDF file, direct download 20.2 MB), Dam im imię na wieki [I will give them an everlasting name. Isaiah 56:5] (in Polish), Drohiczyńskie Towarzystwo Naukowe [The Drohiczyn Scientific Society], pp. 76–102, ISBN 978-83-7257-496-1, retrieved 9 September 2013,

with list of Catholic rescuers of Jews imprisoned at Treblinka, selected testimonies, bibliography, alphabetical indexes, photographs, English language summaries, and forewords by Holocaust scholars.

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Treblinka - ein Todeslager der "Aktion Reinhard", in: "Aktion Reinhard" - Die Vernichtung der Juden im Generalgouvernement, Bogdan Musial (ed.), Osnabrück 2004, pp. 257–281.

- ^ Arad 1987, page 375.

- ^ Alex Bay (2015) [2000]. The Reconstruction of Belzec, featuring 98 photos. Holocaust History.org. Book reference: Belzec. The Nazi Camp for Jews in the Light of Archaeological Sources by Andrzej Kola, translated from Polish by Ewa Józefowicz and Mateusz Józefowicz, published by The Council for the Protection of Memory of Combat and Martyrdom, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Warsaw-Washington. Also in: Archeologists reveal new secrets of Holocaust, Reuters News, 21 July 1998. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

Belzec survivor Rudolf Reder, author of postwar memoir about Belzec wrote that the camp's gas chambers were rebuilt of concrete. No traces of concrete were ever found in modern archaeological studies conducted in 1997–98 by Andrzej Kola, Director of the Archaelogical and Ethnological Institute of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland. Instead, the brick rubble was found in excavations.

- ^ "Belzec", USHMM. Accessed February 5, 2008.

- ^ Rudolf Reder (1946). Bełżec (WorldCat). Preface by Nella Rost (ed.): Wstęp. Kraków : Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna division of the Central Committee of Polish Jews. pp. 1–65. OCLC 186784721. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help). - ^ Yahil, Leni; Friedman, Ina; Galai, Hayah (1991). The Holocaust: The fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Oxford University Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-0-19-504523-9. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ^ Gerstein Report in: Dick de Mildt, In the name of the people Published by Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-411-0185-3.

- ^ Kurt Gerstein, "Gerstein Report" in English translation. Tübingen, 4 May 1945.

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia, "Belzec: Chronology" United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2013.

- ^ Arad 1987, page 102.

- ^ ARC (26 August 2006). "Belzec Camp History". Aktion Reinhard.

- ^ The Holocaust Encyclopedia. "Belzec". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archeologists reveal new secrets of Holocaust", Reuters News, 21 July 1998

- ^ Belzec, Complete Book and Research by Robin O'Neil

- ^ Raul Hilberg. The Destruction of the European Jews. Yale University Press, 1985, p. 1219. ISBN 978-0-300-09557-9

- ^ Blatt 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Blatt 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Chris Webb, C.L. (2007). "Former Members of the SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor describe their experiences in the Sobibor death camp in their own words". Belzec, Sobibor & Treblinka Death Camps. H.E.A.R.T. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

It was a heavy Russian benzine engine – presumably a tank or tractor motor at least 200 horsepower V-motor, 8 cylinders, water cooled (SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs).

- ^ Blatt 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Schelvis, Jules. Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Berg, Oxford & New Cork, 2007, p. 168, ISBN 978-1-84520-419-8.

- ^ "Sobibor Death Camp www.HolocaustResearchProject.org".

- ^ Staff Writer (2006). "Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp: Overview". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ushmm.org.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer (2008). "Majdanek: An Overview". 20th Century History. about.com. ISBN 0-404-16983-X.

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library 2009, Gas Chambers at Majdanek The American-Israeli Cooperative

- ^ Kranz, Tomasz (2005). "Ewidencja zgonow i smiertelnosc wiezniow KL Lublin". 23. Lublin: Zeszyty Majdanka: 7–53.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Reszka, Paweł P. (December 23, 2005). "Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?". Gazeta Wyborcza. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on November 6, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Browning, Christopher R. (1998) [1992]. Arrival in Poland (PDF file, direct download 7.91 MB complete). Penguin Books. pp. 52, 77, 79, 80, 135. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

Also: PDF cache archived by WebCite.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); External link in|quote= - ^ Lawrence, Geoffrey; et al., eds. (1946). "Session 62: February 19, 1946". The Trial of German Major War Criminals: Sitting at Nuremberg, Germany. Vol. 7. London: HM Stationery Office. p. 111. ISBN 1-57588-677-4.

- ^ HOLOCAUST FAQ: Operation Reinhard: A Layman's Guide (2/2). Internet Archive.

- ^ Joshua Brandt (April 22, 2005). "Holocaust survivor gives teens the straight story". Jewish news weekly of Northern California. Archived from the original on November 26, 2005. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Edwin Black, IBM and the Holocaust subtitled The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation (Crown Books, 2001, and Three Rivers Press, 2002)

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C., 1. "German Railways and the Holocaust" 2. "Deportations to Killing Centers"

- ^ Piotrowski 1998, p. 217 - Ukrainian Collaboration.

- ^ ARC (2004). "Erntefest". Occupation of the East. ARC. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ^ "HL-Heidelager: SS-TruppenÜbungsPlatz" (with collection of historical photographs). Historia poligonu Heidelager w Pustkowie (in Polish). Pustkow.Republika.pl. 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Terry Goldsworthy (2010). "Valhalla's Warriors" (Google Book preview). A History of the Waffen-SS on the Eastern Front 1941–1945. Dog Ear Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 1-60844-639-5. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (2011). Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship. Yale University Press. pp. 109, 110, 113. ISBN 0-300-13435-5. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gunnar S. Paulsson (Summer–Autumn 1998). "The Rescue of Jews by Non-Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland" (PDF). Journal of Holocaust Education. 7 (1&2). Frank Cass, London: 19–44. Retrieved 12 Feb 2014.

Keeping in mind that these cases are drawn from published memoirs and from cases on file at Yad Vashem and the Jewish Historical Institute, it is probable that the 5,000 or so Poles who have been recognised as 'Righteous Among the Nations' so far represent only the tip of the iceberg, and that the true number of rescuers who meet the Yad Vashem 'gold standard' is 20, 50, perhaps even 100 times higher (p. 23, § 2; available with purchase).

{{cite journal}}: External link in|quote=|ref=harv(help) - ^ Ewa Kurek (2 August 2012). Polish-Jewish Relations 1939–1945: Beyond the Limits of Solidarity. iUniverse. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-4759-3832-6.

- ^ a b Robert D. Cherry, Annamaria Orla-Bukowska, Rethinking Poles and Jews: Troubled Past, Brighter Future, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN 0-7425-4666-7, Google Print, p.5.

- ^ Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project: Poland

- ^ Mordecai Paldiel, Gentile Rescuers of Jews, page 184. Published by KTAV Publishing House Inc.

- ^ Leszek Sołek (2007). "Anna Poray-Wybranowska – dokumentalistka, autorka książki o ratowaniu Żydów przez Polaków". Konsulat Generalny R.P. (in Polish). Są Wśród Nas. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Ron Riesenbach, The Story of the Survival of the Riesenbach Family

- ^ Chaim Chefer, Righteous of the World: Polish citizens killed while helping Jews During the Holocaust

- ^ Unveiling the Secret City H-Net Review: John Radzilowski

- ^ Hans G. Furth One million Polish rescuers of hunted Jews?. Journal of Genocide Research, Jun99, Vol. 1 Issue 2, p227, 6p; (AN 6025705)

- ^ Mark Paul (October 2007). "Traditional Jewish Attitudes Toward Poles" (PDF file, direct download 933 KB). International Research Center. pp. 4–. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

Source: article "Jews and Poles Lived Together for 800 Years But Were Not Integrated," published by Singer under pen-name I. Warszawski in Forverts (New York, September 17, 1944). Two decades later – in the March 20, 1964 issue of Forverts – Singer wrote again: "My forefathers have lived for centuries in Poland ... with separate language, ideas and religion. I sensed the oddness of this situation ..."

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ GUS. Drugi Powszechny Spis Ludności z dn. 9.XII.1931 r. Seria C. Zeszyt 94a (PDF file, direct download) (in Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, Warszawa 1938. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

Religion and Native Language (total). Section Jewish: 3,113,933 with Yiddish: 2,489,034 and Hebrew: 243,539.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Celia Stopnicka Heller, On the Edge of Destruction..., 1993, Wayne State University Press, 396 pages ISBN 0-8143-2494-0

- ^ Joshua B. Zimmerman. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. Rutgers University Press, 2003.

- ^ Klaus-Peter Friedrich. Collaboration in a "Land without a Quisling": Patterns of Cooperation with the Nazi German Occupation Regime in Poland during World War II. Slavic Review, Vol. 64, No. 4, (Winter, 2005), pp. 711–746. JSTOR

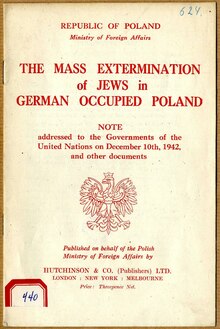

- ^ "Note to the Governments of the United Nations - December 10th, 1942". Republika.pl. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ David Cesarani, Sarah Kavanaugh, Holocaust Published by Routledge. Page 64.

- ^ Dariusz Stola. The Polish government in exile and the Final Solution: What conditioned its actions and inactions? In: Joshua D. Zimmerman, ed. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. Rutgers University Press, 2003.

- ^ Polacy ratujący Żydów w latach II wojny światowej [Poles rescuing Jews during World War II] (PDF). Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance. 2008. pp. 7, 18, 23, 31. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

Kierownictwo Walki Cywilnej w "Biuletynie Informacyjnym" ostrzega "szmalcowników" i denuncjatorów przed konsekwencjami grożącymi im ze strony władz państwa podziemnego. [p.37 in PDF] Ot, widzi pan, sprawa jednej litery sprawia ogromną różnicę. Ratować i uratować! Ratowaliśmy kilkadziesiąt razy więcej ludzi, niż uratowaliśmy. – Władysław Bartoszewski [p.7]

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Referenced Material". Isurvived.org. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ Grabowski, Jan (2004). "Ja tego żyda znam!" : szantażowanie żydów w Warszawie, 1939–1943 / "I know this Jew!": blackmailing of the Jews in occupied Warsaw 1939–1945 (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland: Wydawn. IFiS PAN : Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów. ISBN 83-7388-058-5. OCLC 60174481.

- ^ a b Klaus-Peter Friedrich. Collaboration in a "Land without a Quisling": Patterns of Cooperation with the Nazi German Occupation Regime in Poland during World War II. Slavic Review, Vol. 64, No. 4, (Winter, 2005), pp. 711–746. Friedrich cites Lukas 2001 for the lower figure and Czeslaw Madajczyk, "'Teufelswerk': Die nationalsozialistische Besatzungspolitik in Polen," in Eva Rommerskirchen, ed., Deutsche und Polen 1945–1995: Anndherungen-Zbliienia (Diisseldorf, 1996) for the one million figure.

- ^ a b John Connelly, Why the Poles Collaborated so Little: And Why That Is No Reason for Nationalist Hubris, Slavic Review, Vol. 64, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 771–781, JSTOR publication online.

- ^ PWN (2016). "Rosja. Polonia i Polacy". Encyklopedia PWN. Stanisław Gregorowicz. Polish Scientific Publishers PWN.

- ^ Wojciech Roszkowski (4 November 2008). "Historia: Godzina zero". Tygodnik.Onet.pl weekly. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Erwin and Riva Baker Memorial Collection (2001). Yad Vashem Studies. Wallstein Verlag. pp. 57–. ISSN 0084-3296.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski, Piotr Wróbel, Richard J. Kozicki, Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, ISBN 0-313-26007-9, Google Print, pp. 110, 538. For Soviet deportations more recent IPN findings, see Wojciech Materski and Tomasz Szarota (2009), Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe, Introduction. ISBN 978-83-7629-067-6.

- ^ Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski, "Jedwabne: The Politics of Apology", presented at the Panel Jedwabne – A Scientific Analysis, Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, Inc., June 8, 2002, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- ^ Tomasz Strzembosz, "Inny obraz sąsiadów" archived by Internet Wayback Machine

- ^ Christopher R. Browning, Jurgen Matthaus, The Origins of the Final Solution, page 262 Publisher University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8032-5979-4

- ^ Michael C. Steinlauf. Bondage to the Dead. Syracuse University Press, p. 30.

- ^ Paweł Machcewicz, "Płomienie nienawiści", Polityka 43 (2373), October 26, 2002, p. 71–73 The Findings

- ^ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 194-. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ USHMM. "Lwów". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on March 7, 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dr. Frank Grelka (2005). Ukrainischen Miliz. Viadrina European University: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 283–284. ISBN 3-447-05259-7. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

RSHA von einer begrüßenswerten Aktivitat der ukrainischen Bevolkerung in den ersten Stunden nach dem Abzug der Sowjettruppen.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Tarnopol Historical Background". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ Talking with the willing executioners. Haaretz.com 18 May 2009 via Internet Archive. A horrific page of history unfolded last Monday in Ukraine. It concerned the gruesome and untold story of a spontaneous pogrom by local villagers against hundreds of Jews in a town [now suburb] south of Ternopil in 1941. Not one, but five independent witnesses recounted the tale.

- ^ Dieter Pohl. Hans Krueger and the Murder of the Jews in the Stanislawow Region (PDF). Yad Vashem Resource Center. pp. 12/13, 17/18, 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014 – via direct download, PDF 95 KB.

It is clear that a massacre of such proportions under German civil administration was virtually unprecedented.

Also in: Andrea Löw, USHMM (10 June 2013). "Stanisławów" (PDF). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 12 November 2015 – via Internet Archive.From The USHMM Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945.

- ^ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998), Poland's Holocaust. McFarland, page 209. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3. Also in: Eugeniusz Mironowicz (2014). "Okupacja niemiecka na Białorusi". History of Belarus, mid 18th century until the 20th century (Historia Białorusi od połowy XVIII do XX w.). Związek Białoruski w RP, Katedra Kultury Białoruskiej Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku. Idea sojuszu niemiecko-białoruskiego (German-Belarusian Alliance). Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2015 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Jedwabne Tragedy: Final Findings". Info-poland.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- ^ Alexander B. Rossino, Polish 'Neighbors' and German Invaders: Contextualizing Anti-Jewish Violence in the Białystok District during the Opening Weeks of Operation Barbarossa. Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 16 (2003). Referenced citations: #58. The Partisan: From the Valley of Death to Mount Zion by Yitzhak Arad; #59. The Lesser of Two Evils: Eastern European Jewry under Soviet Rule, 1939–1941 by Dov Levin; and #97. Abschlussbericht, 17 March 1964 in ZStL, 5 AR-Z 13/62, p. 164. Internet Archive.

- ^ Piotr Wróbel (2006). Polish-Jewish Relations. Northwestern University Press. pp. 391–396. ISBN 0-8101-2370-3. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, "The Politics of Apology and Contrition" by prof. Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski, Georgetown University, Washington DC, June 8, 2002.

- ^ Steven J Zaloga (1982). "The Underground Army". Polish Army, 1939–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-417-4.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ The Polish Army 1939–45.

- ^ Piotrowski 1998, p. 95 - "A quote verifying the information".

- ^ Piotrowski 1998, p. 96 - "Verification".

- ^ Piotrowski 1998, pp. 77–142 - Polish Collaboration.

- ^ Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, The Dialectics of Pain Glaukopis, vol. 2/3 (2004–2005). See also: John S. Micgiel, "'Frenzy and Ferocity': The Stalinist Judicial System in Poland, 1944–1947, and the Search for Redress," The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies [ Pittsburgh], no. 1101 (February 1994): 1–48. For concurring opinions see: Krzysztof Lesiakowski and Grzegorz Majchrzak interviewed by Barbara Polak, "O Aparacie Bezpieczeństwa," Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 6 (June 2002): 4–24; Barbara Polak, "O karach śmierci w latach 1944–1956," Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 11 (November 2002): 4–29.

- ^ Aleksiun, Natalia. "Beriḥah". YIVO.

Suggested reading: Arieh J. Kochavi, "Britain and the Jewish Exodus ... ," Polin 7 (1992): pp. 161–175

- ^ a b Devorah Hakohen, Immigrants in turmoil: mass immigration to Israel and its repercussions ... Syracuse University Press, 2003 - 325 pages. Page 70. ISBN 0-8156-2969-9

- ^ Marrus, Michael Robert; Aristide R. Zolberg (2002). The Unwanted: European Refugees from the First World War Through the Cold War. Temple University Press. p. 336. ISBN 1-56639-955-6.

This gigantic effort, known by the Hebrew code word Brichah(flight), accelerated powerfully after the Kielce pogrom in July 1946

- ^ Kochavi, Arieh J. (2001). Post-Holocaust Politics: Britain, the United States & Jewish Refugees, 1945–1948. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. xi. ISBN 0-8078-2620-0.

- ^ Natalia Aleksiun, The Roman Catholic Church and the Jewish Question in Poland, 1944–1948. Page 12–13.

- ^ "The Church and the Memory of the Shoah: The Catholic Press in Italy, 1945–1947". Jews, Catholics, and the Burden of History. Oxford University Press. 2005. p. 37: "Notes" (not shown in Google Books preview). ISBN 0-19-530491-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) [verification needed] - ^ David J. Landau, Caged — A story of Jewish Resistance, Pan Macmillan Australia, 2000, ISBN 0-7329-1063-3. Quote: "The tragic end of the Ghetto [in Warsaw] could not have been changed, but the road to it might have been different under a stronger leader. There can be no doubt that if the Uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto had taken place in August—September 1942, when there were still 300,000 Jews, the Germans would have paid a much higher price."

- ^ Laura Jockusch, Tamar Lewinsky, Paradise Lost? Postwar Memory of Polish Jewish Survival in the Soviet Union, full text downloaded from Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 24, Number 3, Winter 2010.

- ^ Devorah Hakohen (2003), Immigrants in turmoil, page 70.

- ^ a b David Engel. "Poland. Liberation, Reconstruction, and Flight (1944–1947)" (PDF). YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2011 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Philipp Ther, Ana Siljak (2001). Redrawing nations: ethnic cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 138. ISBN 0-7425-1094-8. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Michael C. Steinlauf. "Poland.". In: David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig. The World Reacts to the Holocaust. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- ^ Lukas 1989; also in Lukas 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Albert Stankowski, with August Grabski and Grzegorz Berendt; Studia z historii Żydów w Polsce po 1945 roku, Warszawa, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny 2000, pp. 107–111. ISBN 83-85888-36-5

- ^ Timothy Snyder (December 20, 2012). "Hitler's Logical Holocaust". New York Review of Books.

- ^ "History of the Holocaust. Remembering the Past, Ensuring the Future". Open registration. International March of the Living 2012–2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

References

- Arad, Yitzhak (1999) [1987]. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Google Book, search inside). Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34293-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blatt, Thomas (2004). The Forgotten Revolt. H.E.P. ISBN 978-0-9649442-0-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dobroszycki, Lucjan (1994). Survivors of the Holocaust in Poland: A Portrait Based on Jewish Community Records, 1944–1947. Yivo Institute for Jewish Research, M.E. Sharpe. p. 164. ISBN 1-56324-463-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Engel, David (1993). Facing a Holocaust: The Polish Government-in-exile and the Jews, 1943–1945 (Google Book preview). UNC Press Books. p. 317. ISBN 0-8078-2069-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lukas, Richard C. (1989). Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-1692-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lukas, Richard C. (2001). The forgotten Holocaust: the Poles under German occupation, 1939–1944. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-0901-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Musiał, Bogdan (ed.), "Treblinka — ein Todeslager der Aktion Reinhard", in: Aktion Reinhard — Die Vernichtung der Juden im Generalgouvernement, Osnabrück 2004, pp. 257–281.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) OCLC WorldCat. - Poray, Anna (2007). "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous". Those Who Risked Their Lives. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Paulsson, Gunnar S. (March 29, 2003), 'Polish Complicity In The Shoah Is A Myth' (online, Special Reports: Commentary).

- Paulsson, Gunnar S. (May 5, 2008), On the Marginal Role of Poles In Abetting the Nazi Perpetrators Isurvived.org

- Paulsson, Gunnar S. Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940–1945. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-300-09546-3, Review.

- Naomi Samson, Hide: A Child's View of the Holocaust 2000, 194 pages.

- Eric Sterling, John K. Roth, Life in the Ghettos During the Holocaust 2005, 356 pages.