Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Woodhull | |

|---|---|

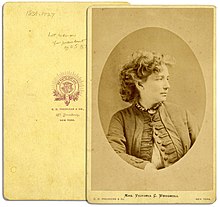

Photograph by Mathew Brady, c. 1870 | |

| Born | Victoria California Claflin September 23, 1838 Homer, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | June 9, 1927 (aged 88)[1] Bredon's Norton, Worcestershire, England |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for |

|

| Political party | Equal Rights |

| Spouses | Canning Woodhull

(m. 1853; div. 1865) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Victoria Claflin Woodhull (born Victoria California Claflin; September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), later Victoria Woodhull Martin, was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for president of the United States in the 1872 election. While many historians and authors agree that Woodhull was the first woman to run for the presidency,[2] some disagree with classifying it as a true candidacy because according to the Constitution she would have been too young to be President if elected.[3]

An activist for women's rights and labor reforms, Woodhull was also an advocate of "free love", by which she meant the freedom to marry, divorce and bear children without social restriction or government interference.[4] "They cannot roll back the rising tide of reform," she often said. "The world moves."[5]

Woodhull twice went from rags to riches, her first fortune being made on the road as a magnetic healer[6] before she joined the spiritualist movement in the 1870s.[7] Authorship of many of her articles is disputed (many of her speeches on these topics were collaborations between Woodhull, her backers, and her second husband, Colonel James Blood[8]). Together with her sister, Tennessee Claflin, she was the first woman to operate a brokerage firm on Wall Street,[9] making a second, and more reputable fortune.[10] They were among the first women to found a newspaper in the United States, Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, which began publication in 1870.[11]

Woodhull was politically active in the early 1870s when she was nominated as the first woman candidate for the United States presidency.[9] Woodhull was the candidate in 1872 from the Equal Rights Party, supporting women's suffrage and equal rights; her running mate (unbeknownst to him) was abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass.[12] Her campaign inspired at least one other woman – apart from her sister – to run for Congress.[9] A check on her activities occurred when she was arrested on obscenity charges a few days before the election. Her paper had published an account of the alleged adulterous affair between the prominent minister Henry Ward Beecher and Elizabeth Richards Tilton that had rather more detail than was considered proper at the time. However, it all added to the sensational coverage of her candidacy.[13]

Early life and education

[edit]Victoria California Claflin was born the seventh of ten children (six of whom survived to maturity),[14] in the rural frontier town of Homer, Licking County, Ohio. Her mother, Mrs Roxanna "Roxy"[14] Hummel Claflin, was born to unmarried parents and was illiterate.[15] She had become a follower of the Austrian mystic Franz Mesmer and the new spiritualist movement.[16] Her father, Reuben Buckman "Buck" Claflin, Esq.,[14][17][18] was a con man, lawyer and snake oil salesman.[14] He came from an impoverished branch of the Massachusetts-based Scots-American Claflin family, semi-distant cousins to Massachusetts Governor William Claflin.[18]

Woodhull was whipped by her father, according to biographer Theodore Tilton.[19] Biographer Barbara Goldsmith claimed she was also starved and sexually abused by her father when still very young.[20] She based her incest claim on a statement in Theodore Tilton's biography: "But the parents, as if not unwilling to be rid of a daughter whose sorrow was ripening her into a woman before her time, were delighted at the unexpected offer."[21][22] Biographer Myra MacPherson disputes Goldsmith's claim that "Vickie often intimated that he sexually abused her" as well as the accuracy of Goldsmith's saying that "Years later, Vickie would say that Buck made her 'a woman before my time.'"[20] Macpherson wrote, "Not only did Victoria not say this, there was no 'often' involved, nor was it about incest."[23]

Woodhull believed in spiritualism – she referred to "Banquo's Ghost" from Shakespeare's Macbeth – because it gave her belief in a better life. She said that she was guided in 1868 by Demosthenes to what symbolism to use supporting her theories of Free Love.[24][page needed]

As they grew older, Victoria became close to her sister Tennessee Celeste Claflin (called Tennie), seven years her junior and the last child born to the family. As adults, they collaborated in founding a stock brokerage and newspaper in New York City.[14]

By age 11, Woodhull had only three years of formal education, but her teachers found her to be extremely intelligent. She was forced to leave school and home with her family when her father, after having "insured it heavily,"[6] burned the family's rotting gristmill. When he tried to get compensated by insurance, his arson and fraud were discovered; he was run off by a group of town vigilantes.[6] The town held a "benefit" to raise funds to pay for the rest of the family's departure from Ohio.[6]

Marriages

[edit]First marriage and family

[edit]

When she was 14, Victoria met 28-year-old Canning Woodhull (listed as "Channing" in some records), a doctor from a town outside Rochester, New York. Her family had consulted him to treat the girl for a chronic illness. Woodhull practiced medicine in Ohio at a time when the state did not require formal medical education and licensing. By some accounts, Woodhull abducted Victoria to marry her.[25] Woodhull claimed to be the nephew of Caleb Smith Woodhull, mayor of New York City from 1849 to 1851; he was in fact a distant cousin.[26]

They were married on November 20, 1853.[27][28] Their marriage certificate was recorded in Cleveland on November 23, 1853, when Victoria was two months past her 15th birthday.[6][29]

Victoria soon learned that her new husband was an alcoholic and a womanizer. She often had to work outside the home to support the family. She and Canning had two children, Byron and Zulu (later called Zula) Maude Woodhull.[30] Byron was born with an intellectual disability in 1854, a condition Victoria believed was caused by her husband's alcoholism.[31] Another version recounted that her son's disability was caused by a fall from a window. After their children were born, Victoria divorced her husband and kept his surname.[7]

Second marriage

[edit]About 1866,[32] Woodhull married Colonel James Harvey Blood, who also was marrying for a second time. He had served in the Union Army in Missouri during the American Civil War, and had been elected as city auditor of St. Louis, Missouri.

Free love

[edit]Woodhull's support of free love likely started after she discovered the infidelity of her first husband, Canning. Women who married in the United States during the 19th century were bound into the unions, even if loveless, with few options to escape. Divorce was limited by law and considered socially scandalous. Women who divorced were stigmatized and often ostracized by society. Victoria Woodhull concluded that women should have the choice to leave unbearable marriages.[33][page needed]

Woodhull believed in monogamous relationships, although she also said she had the right to change her mind. The choice to have sex or not was, in every case, the woman's choice, since this would place her in an equal status to the man, who had the capability to physically overcome and rape a woman, whereas a woman did not have that capability with respect to a man.[34] Woodhull said:

To woman, by nature, belongs the right of sexual determination. When the instinct is aroused in her, then and then only should commerce follow. When woman rises from sexual slavery to sexual freedom, into the ownership and control of her sexual organs, and man is obliged to respect this freedom, then will this instinct become pure and holy; then will woman be raised from the iniquity and morbidness in which she now wallows for existence, and the intensity and glory of her creative functions be increased a hundred-fold … .[35]

In this same speech, which became known as the "Steinway speech," delivered on Monday, November 20, 1871, in Steinway Hall, New York City, Woodhull said of free love:

Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere.[36]

Woodhull railed against the hypocrisy of society's tolerating married men who had mistresses and engaged in other sexual dalliances. In 1872, Woodhull publicly criticized well-known clergyman Henry Ward Beecher for adultery. Beecher was known to have had an affair with his parishioner Elizabeth Tilton, who had confessed to it, and the scandal was covered nationally. Woodhull was prosecuted on obscenity charges for sending accounts of the affair through the federal mails, and she was briefly jailed. This added to sensational coverage during her campaign that autumn for the United States presidency.[33][page needed]

Prostitution rumors and stance

[edit]Woodhull spoke out in person against prostitution and considered marriage for material gain a form of it but in her journal, Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, Woodhull expressed support for the legalization of prostitution.[37] A personal account from one of Colonel Blood's friends suggests that Tennessee was held against her will in a brothel until Woodhull rescued her, but this story remains unconfirmed.[37]

Religious shift and repudiation of free love

[edit]While Woodhull's earlier radicalism had stemmed from the Christian socialism of the 1850s, for most of her life, she was involved in Spiritualism and she did not use religious language in her public speeches. However, in 1875, Woodhull began to publicly espouse Christianity and she changed her political stances.[38] She exposed Spiritualist frauds in her periodical, alienating her Spiritualist followers.[39] She wrote articles against promiscuity, calling it a "curse of society".[40] Woodhull repudiated her earlier views on free love, and began idealizing purity, motherhood, marriage, and the Bible in her writings.[41][42][43] She even claimed that some works had been written in her name without her consent.[44] Historians doubt that assertion by Woodhull.[45]

Careers

[edit]Stockbroker

[edit]

Woodhull, with sister Tennessee (Tennie) Claflin, became the first female stockbrokers and in 1870 they opened a brokerage firm on Wall Street. Wall Street brokers were shocked. "Petticoats Among the Bovine and Ursine Animals," the New York Sun headlined.[5] Woodhull, Claflin & Company opened in 1870, with the assistance of the wealthy Cornelius Vanderbilt, an admirer of Woodhull's skills as a medium; he is rumoured to have been Tennie's lover, and to have seriously considered marrying her.[46] Woodhull made a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange by advising clients like Vanderbilt. On one occasion she told him to sell his shares short for 150 cents per stock, which he duly followed, and earned millions on the deal. Newspapers such as the New York Herald hailed Woodhull and Claflin as "the Queens of Finance" and "the Bewitching Brokers."[citation needed] Many contemporary men's journals (e.g., The Days' Doings) published sexualized images of the pair running their firm (although they did not participate in the day-to-day business of the firm), linking the concept of publicly minded, un-chaperoned women with ideas of "sexual immorality" and prostitution.[47]

Newspaper editor

[edit]On the date of May 14, 1870, Woodhull and Claflin used the money they had made from their brokerage to found a newspaper, the Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, which at its height had a national circulation of 20,000. Its primary purpose was to support Victoria Claflin Woodhull for President of the United States. Published for the next six years, feminism was the Weekly's primary interest, but it became notorious for publishing controversial opinions on taboo topics, advocating among other things sex education, free love, women's suffrage, short skirts, spiritualism, vegetarianism, and licensed prostitution. History often states the paper advocated birth control, but some historians disagree. The paper is now known for printing the first English version of Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto in its edition of December 30, 1871, and the paper argued the cause of labor with eloquence and skill. James Blood and Stephen Pearl Andrews wrote the majority of the articles, as well as other able contributors.[47][48]

In 1872, the Weekly published a story that set off a national scandal and preoccupied the public for months. Henry Ward Beecher, a renowned preacher of Brooklyn's Plymouth Church, had condemned Woodhull's free love philosophy in his sermons but a member of his church, Theodore Tilton, disclosed to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a colleague of Woodhull, that his wife had confessed Beecher was committing adultery with her. Provoked by such hypocrisy, Woodhull decided to expose Beecher. He ended up standing trial in 1875, for adultery in a proceeding that proved to be one of the most sensational legal episodes of the era, gripping the attention of hundreds of thousands of Americans: the trial ended with a hung jury, but the church won the case hands down.[24][page needed] On November 2, 1872, Woodhull, Claflin and Col. Blood were arrested and charged with publishing an obscene newspaper and circulating it through the United States Postal Service. In the raid, 3,000 copies of the newspaper were found. It was this arrest and Woodhull's acquittal that propelled Congress to pass the 1873 Comstock Laws.[49][50]

George Francis Train once defended her. Other feminists of her time, including Susan B. Anthony, disagreed with her tactics in pushing for women's equality. Some characterized her as opportunistic and unpredictable; in one notable incident, she had a run-in with Anthony during a meeting of the National Women's Suffrage Association (NWSA). (The radical NWSA later merged with the conservative American Women's Suffrage Association [AWSA] to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association.)

Women's rights advocate

[edit]Woodhull learned how to infiltrate the all-male domain of national politics and arranged to testify on women's suffrage before the House Judiciary Committee.[32] In December 1870, she submitted a memorial in support of the New Departure to the House Committee.[9][51] She read the memorial aloud to the Committee, arguing that women already had the right to vote – all they had to do was use it – since the 14th and 15th Amendments guaranteed the protection of that right for all citizens.[52] The simple but powerful logic of her argument impressed some committee members. Learning of Woodhull's planned address, suffrage leaders postponed the opening of the 1871 National Woman Suffrage Association's third annual convention in Washington in order to attend the committee hearing. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Isabella Beecher Hooker, saw Woodhull as the newest champion of their cause. They applauded her statement: "[W]omen are the equals of men before the law, and are equal in all their rights."[52]

With the power of her first public appearance as a woman's rights advocate, Woodhull moved to the leadership circle of the suffrage movement. Although her constitutional argument was not original, she focused unprecedented public attention on suffrage. Woodhull was the second woman to petition Congress in person (the first was Elizabeth Cady Stanton). Numerous newspapers reported her appearance before Congress. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper printed a full-page engraving of Woodhull, surrounded by prominent suffragists, delivering her argument.[32][53]

First International

[edit]Woodhull joined the International Workingmen's Association, also known as the First International. She supported its goals by articles in her newspaper. In the United States, many Yankee radicals, former abolitionists and other progressive activists, became involved in the organization, which had been founded in England. German-American and ethnic Irish nearly lost control of the organization, and feared its goals were going to be lost in the broad-based, democratic egalitarianism promoted by the Americans. In 1871, the Germans expelled most of the English-speaking members of the First International's U.S. sections, leading to the quick decline of the organization, as it failed to attract the ethnic working class in America.[54] Karl Marx commented disparagingly on Woodhull in 1872, and expressed approval of the expulsions.[55]

Recent scholarship has shown Woodhull to have been a far more significant presence in the socialist movement than previous historians had allowed.[56][57] Woodhull thought of herself as a revolutionary and her conception of social and political reorganization was, like Marx, based upon economics. In an article titled "Woman Suffrage in the United States" in 1896, she concluded that "suffrage is only one phase of the larger question of women's emancipation. More important is the question of her social and economic position. Her financial independence underlies all the rest."[58] Ellen Carol DuBois refers to her as a "socialist feminist."[59]

Presidential candidate

[edit]

On April 2, 1870, Woodhull's letter to the editor of the New York Herald was published, announcing her candidacy.[60]

Woodhull was nominated for president of the United States by the newly formed Equal Rights Party on May 10, 1872, at Apollo Hall, New York City. A year earlier, she had announced her intention to run. Also in 1871, she publicly spoke out against the government only being composed of men; she proposed the development of a new constitution and the creation of a new government a year thence.[61] Her nomination was ratified at the convention on June 6, 1872, making her the first woman candidate.[62]

Woodhull's campaign was also notable because Frederick Douglass was nominated as its vice-presidential candidate, even though he did not take part in the convention. He did not acknowledge his nomination and did not play any active role in the campaign.[12] His nomination stirred up controversy about the mixing of white and black people in public life, and fears of miscegenation. The Equal Rights Party hoped to use the nominations to reunite suffragists with African-American civil rights activists, because the exclusion of female suffrage from the Fifteenth Amendment two years earlier had caused a substantial rift between the groups.[citation needed]

Having been vilified in the media for her support of free love, Woodhull devoted an issue of Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly (November 2, 1872) to an alleged adulterous affair between Elizabeth Tilton and Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, a prominent Protestant minister in Brooklyn. He supported female suffrage but had lectured against free love in his sermons. Woodhull published the article to highlight what she saw as a sexual double standard between men and women.[63]

That same day, a few days before the presidential election, U.S. Federal Marshals arrested Woodhull, her second husband, Colonel James Blood, and her sister Tennie on charges of "publishing an obscene newspaper" because of the content of this issue.[64] The sisters were held in the Ludlow Street Jail for the next month, a place normally reserved for civil offenses but that also held more hardened criminals. The arrest was arranged by Anthony Comstock, the self-appointed moral defender of the nation at the time. Opponents raised questions about censorship and government persecution. The three were acquitted on a technicality six months later, but the arrest prevented Woodhull from attempting to vote during the 1872 presidential election. With the publication of the scandal, Theodore Tilton, Elizabeth's husband, sued Beecher for "criminal conversation" (adultery) and alienation of affection. The 1875 trial was sensationalized across the nation and resulted in a hung jury.[24][page needed]

Woodhull received no electoral votes in the election of 1872, an election in which six different candidates received at least one electoral vote, and a negligible, but unknown, percentage of the popular vote. A man in Texas said that he had voted for her, saying he was casting his vote against Grant.[37]

Woodhull again tried to gain nominations for the presidency in 1884 and 1892. Newspapers reported that her 1892 attempt culminated in her nomination by the "National Woman Suffragists' Nominating Convention" on September 21. Marietta L. B. Stow of California was nominated as the candidate for vice president. The convention was held at Willard's Hotel in Boonville, New York, and Anna M. Parker was its president.[65] Some women's suffrage organizations repudiated the nominations, claiming that the nominating committee was unauthorized.[66] Woodhull was quoted as saying that she was "destined" by "prophecy" to be elected president of the United States in the upcoming election.[citation needed]

Life in England and third marriage

[edit]

In October 1876, Woodhull divorced her second husband, Colonel Blood. After Cornelius Vanderbilt's death in 1877, William Henry Vanderbilt paid Woodhull and her sister Claflin $1,000 (equivalent to $29,000 in 2023[67]) to leave the country because he was worried they might testify in hearings on the distribution of the elder Vanderbilt's estate. The sisters accepted the offer and moved to Great Britain in August 1877.[68]

She made her first public appearance as a lecturer at St. James's Hall in London on December 4, 1877. Her lecture was called "The Human Body, the Temple of God," a lecture which she had previously presented in the United States. Present at one of her lectures was the banker John Biddulph Martin. They began to see each other and married on October 31, 1883. His family disapproved of the union.[69]

From then on, she was known as Victoria Woodhull Martin. Under that name, she published the magazine The Humanitarian from 1892 to 1901 with help from her daughter, Zula Woodhull. Her husband John died in 1897. After 1901, Martin gave up publishing and retired to the country, establishing residence at Norton Park, Bredon's Norton, Worcestershire, where she built a village school with Tennessee and Zula. Through her work at the Bredon's Norton school, she became a champion for education reform in English village schools with the addition of kindergarten curriculum.[70]

She was active in the pioneering days of female motorists, with the Ladies' Automobile Club, and was reputed to have been the first woman to drive a car in Hyde Park, London and in the English country roads.[71]

Views on abortion and eugenics

[edit]Woodhull expressed thoughts on abortion:

Every woman knows that if she were free, she would never bear an unwished-for child, nor think of murdering one before its birth.[72]

In one of her speeches, she states:

The rights of children, then, as individuals, begin while yet they are in foetal life. Children do not come into existence by any will or consent of their own.[73]

At the Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly, on an essay called When Is It Not Murder to Take a Life?, she asserts:

Many women who would be shocked at the very thought of killing their children after birth, deliberately destroy them previously. If there is any difference in the actual crime we should be glad to have those who practice the latter, point it out. The truth of the matter is that it is just as much a murder to destroy life in its embryotic condition, as it is to destroy it after the fully developed form is attained, for it is the self-same life that is taken.[74]

Later in the same essay she asks:

Can any one suggest a better than to so situate woman, that she may never be obligated to conceive a life she does not desire shall be continuous?[74]

Woodhull also promoted eugenics, which was popular in the early 20th century. Her views on eugenics tied into her views on abortion, because she blamed abortion for assorted problems with pregnancies.[75] Her interest in eugenics might have been motivated by the profound intellectual impairment of her son. She advocated, among other things, sex education, "marrying well," and pre-natal care as a way to bear healthier children and prevent mental and physical disease. Her writings express views which are closer to the views of anarchist eugenicists, rather than the views of coercive eugenicists like Sir Francis Galton. In 2006, publisher Michael W. Perry discovered writings which show that Woodhull supported the forcible sterilization of people who she considered unfit to breed. He published these writings in his book "Lady Eugenist". He cited a New York Times article from 1927 in which she concurred with the ruling of the case Buck v. Bell. This was in stark contrast to her earlier works in which she advocated social freedom and opposed governmental interference in matters of love and marriage.[citation needed]

Woodhull Martin died on June 9, 1927, at Norton Park in Bredon's Norton.[76]

Legacy and honors

[edit]

Woodhull was photographed several times by Mathew Brady, well known for his photographs of the American Civil War.

There is a wall memorial to Victoria Woodhull Martin at Tewkesbury Abbey in England.[77]

A historical marker outside the Homer Public Library in Licking County, Ohio describes Woodhull as the "First Woman Candidate For President of the United States."[78]

There is a memorial clock tower in her honor at the Robbins Hunter Museum, Granville, Ohio. A likeness of Victoria made of linden wood appears on the hours.[79]

The 1980 Broadway musical Onward Victoria was inspired by Woodhull's life.[80]

The Woodhull Institute for Ethical Leadership was founded by Naomi Wolf and Margot Magowan in 1997.[81]

In 2001, Victoria Woodhull was posthumously inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[82]

The Woodhull Sexual Freedom Alliance is an American human rights and sexual freedom advocacy organization, it was founded in 2003, and it is named in honor of Victoria Woodhull.

She was honored by the Office of the Manhattan Borough President in March 2008 and she was also included on a map of historical sites which are related or dedicated to important women.[83]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Mrs. President | |

On September 26, 2008, she was posthumously awarded the "Ronald H. Brown Trailblazer Award" from the St. John's University School of Law in Queens, New York. Mary L. Shearer, owner of the registered trademark Victoria Woodhull and a great-granddaughter of Col. James H. Blood's step-son, accepted the award on Victoria Woodhull's behalf. Trailblazer Awards are presented "to individuals whose work and activities in the business and community demonstrate a commitment to uplifting under-represented groups and individuals."[85]

Victoria Bond composed the opera Mrs. President about Woodhull.[86] It premiered in 2012 in Anchorage, Alaska.[86]

In March 2017, Amazon Studios announced production of a movie based on her life, produced by and starring Brie Larson as Victoria Woodhull.[87]

Bibliography

[edit]- 2010 - Selected writings of Victoria Woodhull. Suffrage, free love, and eugenics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ISBN 978-0-8032-1647-1[88]

Literature

[edit]- 2000 - Jacqueline McLean. Victoria Woodhull. First woman presidential candidate. Morgan Reynolds ISBN 9781883846473

- 2004 - Amanda Frisken. Vicoria Woodhull's sexual revolution. Political theater and the popular press in nineteenthe-century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press ISBN 0-8122-3798-6

- 2010 - Selected writings of Victoria Woodhull. Suffrage, free love, and eugenics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ISBN 978-0-8032-1647-1[88]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Victoria Woodhull Martin certified death certificate". victoria-woodhull.com. Obtained from the General Register Office, UK. June 17, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ^ Finan, Christopher (2022). How Free Speech Saved Democracy. Lebanon, NH: Truth To Power. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9781586422981.

- ^ Hampson, Rick. "First woman to run for president — 'Mrs. Satan' — was no Hillary Clinton". USA TODAY.

- ^ Kemp, Bill (November 15, 2016). "'Free love' advocate Victoria Woodhull excited Bloomington". The Pantagraph. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Woman Who Ran for President – in 1872". The Attic. May 3, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson 1956, p. 46.

- ^ a b Johnson 1956, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Johnson 1956, pp. 86, 87.

- ^ a b c d Katz, Elizabeth D. (July 30, 2021). "Sex, Suffrage, and State Constitutional Law: Women's Legal Right to Hold Public Office". Yale Journal of Law & Feminism. Rochester, NY. SSRN 3896499.

- ^ "Before Hillary eyed presidency, there was Ohio's 'Mrs. Satan'.. Toronto Star, October 22, 2016. p. IN4. by Rick Hampson of USA Today.

- ^ The Revolution, a weekly newspaper founded by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, had begun publication two years earlier in 1868.

- ^ a b Trotman, C. James (2011). Frederick Douglass: A Biography. Penguin Books. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-313-35036-8.

- ^ For an account of the arrest, see "The Claflin Family: Arrest of Victoria Woodhull, Tennie C. Claflin and Col. Blood – They are Charged with Publishing an Obscene Newspaper," The New York Times. November 3, 1872, page 1.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson 1956, p. 45

- ^ Goldsmith 1998, p. 20 (Alfred A. Knopf edition - ISBN 0-394-55536-8).

- ^ "Move Over, Hillary! Victoria Woodhull Was the First Woman to Run for U.S. President". Vogue. April 13, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ 1850 federal census, Licking, Ohio; Series M432, Roll 703, p. 437; father listed as Buckman, brothers incorrectly transcribed as Hubern (Hubert) and Malven (Melvin).

- ^ a b Wight, Charles Henry, Genealogy of the Claflin Family, 1661–1898. New York: Press of William Green. 1903. passim (use index)

- ^ Tilton 1871, p. 4.

- ^ a b Goldsmith 1998, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Tilton 1871, p. 14.

- ^ Goldsmith 1998, p. 457.

- ^ MacPherson 2014, p. 346.

- ^ a b c Goldsmith 1998.

- ^ Prioleau, Elizabeth. Seductress: Women Who Ravished the World and Their Lost Art of Love. Penguin, 2004, p. 222

- ^ Coates, H.T. Woodhull Genealogy: The Woodhull Family in England and America, 1904 pp. 159, 211.

- ^ Gabriel 1998, p. 12.

- ^ ""Ohio, County Marriages, 1789–2013, index and images, FamilySearch "Marriage records 1849–1854 vol 5 > image 273 of 334; county courthouses, Ohio". familysearch.org. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ Underhill 1996, p. 24.

- ^ "Woodhull, Zula Maude". Who's Who. 59: 1930. 1907.

- ^ Noll, Steven and Trent, James. Mental Retardation in America: A Historical Reader. NYU, 2004, pp. 73–75

- ^ a b c Johnson 1956, p. 47.

- ^ a b Dubois & Dumenil 2012.

- ^ Dworkin, Andrea (1987). "Intercourse". Chapter 7: "Occupation/Collaboration.

- ^ "And the truth shall make you free". A speech on the principles of social freedom, delivered in Steinway hall, Nov. 20, 1871, by Victoria C. Woodhull, pub. Woodhull & Claflin, New York, 1871.

- ^ "Victoria Woodhull, Abandoned Woman?". www.victoria-woodhull.com. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Victoria Woodhull, the Spirit to Run the White House". www.victoria-woodhull.com. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Gabriel 1998, p. 240.

- ^ Gabriel 1998, p. 240f.

- ^ "Mrs. Victoria Woodhull's work". Humanitarian. Vol. 1, no. 6. December 1892. p. 100. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Rugoff, Milton (2018). The Gilded Age. Newbury: New Word City, Inc. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-64019-134-1. OCLC 1029760382. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Hayden 2013, p. 30.

- ^ Gabriel 1998, p. 247.

- ^ Frisken 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Hayden 2013, p. 222.

- ^ Johnson 1956, p. 86.

- ^ a b Johnson 1956, p. 87.

- ^ "A Woman for President?; Perhaps you didn't know the fair sex had ever tried for the office, but one lady polled 4,159 votes in 1884". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Clafin Family; Arrest of Victoria Woodhull, Tennie C. Claflin and Col. Blood – They are Charged with Publishing an Obscene Newspaper". The New York Times.

- ^ Lefkowitz Horowitz, Helen. Rereading Sex. New York: Random House, 2002.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Benjamin Butler, while a member of Congress, wrote the memorial for her. Shaplen, Robert, Free Love: The Story of a Great American Scandal, New York: McNally Editions, 2024, p. 144; originally published in 1954 by Alfred A. Knopf as Free Love and Heavenly Sinners.

- ^ a b Constitutional equality. To the Hon. the Judiciary committee of the Senate and the House of representatives of the Congress of the United States ... Most respectfully submitted. Victoria C. Woodhull. Dated New York, January 2, 1871

- ^ Susan Kullmann, "Legal Contender... Victoria C. Woodhull, First Woman to Run for President". Accessed 2009.05.29.

- ^ Messer-Kruse, Timothy (1998). The Yankee International: Marxism and the American Reform Tradition, 1848–1876. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-0-8078-4705-3.

- ^ Marx, Carl (May 28, 1872). "Notes on the "American split"". Marx-Engels Archive. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ Hamilton, Neil A. (2002). Rebels and Renegades: A Chronology of Social and Political Dissent in the United States. Taylor & Francis. p. 128.

- ^ Frisken 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Stokes, John (2000). Eleanor Marx (1855–1898): Life, Work, Contacts. Ashgate. pp. 158–170.

- ^ DuBois, Ellen Carol (1998). Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights. NYU Press. p. 256.

- ^ "Victoria Woodhull announces her candidacy on Apr. 2, 1870 in the New York Herald". The New York Herald. April 2, 1870. p. 5. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ A Lecture on Constitutional Equality, also known as The Great Secession Speech, speech to Woman's Suffrage Convention, New York, May 11, 1871, excerpt quoted in Gabriel 1998, pp. 86–87, n. 13 (author Mary Gabriel journalist, Reuters News Service). Also excerpted, differently, in Underhill 1996, pp. 125–126.

- ^ "The First Woman To Run For President: Victoria Woodhull (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Woodhull, Victoria C. (2010). "14: The Beecher-Tilton Scandal Case". In Carpenter, Cari M (ed.). Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and Eugenics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2995-2. OCLC 794700538 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Arrest of Victoria Woodhull, Tennie C. Claflin and Col. Blood. They are Charged with Publishing an Obscene Newspaper". The New York Times. November 3, 1872. Retrieved June 27, 2008.

The agent of the Society for the Suppression of Obscene Literature, yesterday morning, appeared before United States Commissioner Osborn and asked for a warrant for the arrest of Mrs. Victoria C. Woodhull and Miss Tennie ...

- ^ "Daily public ledger. [volume] (Maysville, Ky.) 1892-191?, September 23, 1892, Image 3". ISSN 2157-3484. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ "Pittsburg dispatch. [volume] (Pittsburg [Pa.]) 1880-1923, September 28, 1892, Image 9". p. 9. ISSN 2157-1295. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Havelin, K. (2006). Victoria Woodhull: Fearless Feminist. Trailblazer biography. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8225-5986-3. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Felsenthal, Carol. "The Strange Tale of the First Woman to Run for President". Politico Magazine. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ "Mrs. Martin Starts English School War; Sister of Tennessee Claflin, Once in Public Eye Here, Again a Reformer. Stirs Village Dogberrys Runs Up-to-Date School on Her Own Estate and Draws Pupils from Old-Fashioned "Three Rs" Seats of Learning". The New York Times.

- ^ "First Lady Motorist". Westminster Gazette. June 10, 1904. p. 10. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Wheeling, West Virginia Evening Standard (1875).

- ^ Woodhull, Victoria. "Woodhull, Children – Their Rights and Privileges". Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Woodhull, Victoria. "When is it not murder to take a life?" (PDF). p. 11. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ "My Word on Abortion and Other Things". Woodhull and Claflins Weekly. September 23, 1871.

- ^ "Victoria Martin, Suffragist, Dies. Nominated for President of the United States as Mrs. Woodhull in 1872. Leader of Many Causes. Had Fostered Anglo-American Friendship Since She Became Wife of a Britisher ...". The New York Times. June 11, 1927.

- ^ Photo taken by RobertFrost1960 on September 21, 2010, accessed June 9, 2011.

- ^ Hart, Ted (July 29, 2016). "Licking Co. native ran for president in 1872, the first woman ever to do so". NBC4i.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ "Victoria Claflin Woodhull: Phoenix Rising". Robbins Hunter Museum. December 19, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ The Performing Arts: A Guide to the Reference Literature. Libraries Unlimited. 1994. ISBN 978-0-87287-982-9.

- ^ Woodhull Institute Archived March 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine; Retrieved April 3, 2013

- ^ "National Women's Hall of Fame". Greatwomen.org. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ^ "Women's Rights, Historic Sites Location List". Office of Manhattan Borough President Scott M. Stringer. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ^ "Get to Know The First Woman Who Ever Ran for President". The Takeaway. WNYC. October 28, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Baynes, Leonard M. (Fall 2010). "The Celebration of the 40th Anniversary of Ronald H. Brown's Graduation from St. John's School of Law". Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development. 25 (1): 14.

- ^ a b Dunham, Mike. "Review: Opera about first woman to run for president debuts in Anchorage | Arts and Culture". Alaska Dispatch News. Anchorage. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (March 22, 2017). "Brie Larson to Play First Female U.S. Presidential Candidate Victoria Woodhull in Amazon Film". Variety. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Cari M. Carpenter (ed.). Selected writings of Victoria Woodhull. Suffrage, free love, and eugenics

Cited works

[edit]- Dubois, Ellen Carol; Dumenil, Lynn (2012). Through Women's Eyes: An American History with Documents. Bedford Books / St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0312676032.

- Johnson, Gerald W. (June 1956). "Dynamic Victoria Woodhull". American Heritage. 7 (4).

- Frisken, Amanda (2012). Victoria Woodhull's Sexual Revolution: Political Theater and the Popular Press in Nineteenth-Century America. EBL-Schweitzer. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812201987. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- Gabriel, Mary (1998). Notorious Victoria: The Life of Victoria Woodhull Uncensored. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books. ISBN 1-56512-132-5.

- Goldsmith, Barbara (1998). Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull. New York City: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-095332-2.

- Hayden, W. (2013). Evolutionary Rhetoric: Sex, Science, and Free Love in Nineteenth-Century Feminism. Studies in Rhetorics and Feminisms. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0809331024.

- MacPherson, Myra (2014). The scarlet sisters : sex, suffrage, and scandal in the Gilded Age. (biography of Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Celeste Claflin). New York City: Twelve. ISBN 978-0446570237. LCCN 2013027618.

- Tilton, Theodore (1871). Biography of Victoria C. Woodhull. New York City: Golden Age. p. 4.

- Underhill, Lois Beachy (1996). The Woman Who Ran for President: The Many Lives of Victoria Woodhull. Bridgehampton, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140256385.

Further reading

[edit]Secondary sources

[edit]- Brough, James (1980). The Vixens. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22688-6.

Historical Fiction

- Caplan, Sheri J. (2013). Petticoats and Pinstripes: Portraits of Women in Wall Street's History. Praeger. ISBN 978-1-4408-0265-2.

- Carpenter, Cari M. (2010). Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and Eugenics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Davis, Paulina W., ed. (1871). A history of the national woman's rights movement for twenty years. New York: Journeymen Printers' Cooperative Association.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Evelina, Nicole (2007). Madame Presidentess: A novel of Victoria Woodhull. Lawson Gartner Publishing. ISBN 978-0996763196.

- Fitzpatrick, Ellen (2016). The Highest Glass Ceiling : Women's Quest for the American Presidency. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-08893-1. LCCN 2015045620.

- Frisken, Amanda (2004). Victoria Woodhull's Sexual Revolution. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3798-6.

- Krull, Kathleen (2004). A Woman for President: The Story of Victoria Woodhull. Walker Childrens. ISBN 978-0802789082.

- Lefkowitz Horowitz, Helen (2000). "Victoria Woodhull, Anthony Comstock, and Conflict over Sex in the United States in the 1870s". The Journal of American History. 87 (2): 403–434. doi:10.2307/2568758. JSTOR 2568758. PMID 17722380.

- Marberry, M.M. (1967). Vicky. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- Meade, Marion (1976). Free Woman. Alfred A. Knopf, Harper & Brothers.

- Riddle, A.G. (1871). The Right of women to exercise the elective franchise under the Fourteenth Article of the Constitution: speech of A.G. Riddle in the Suffrage Convention at Washington, January 11, 1871: the argument was made in support of the Woodhull memorial, before the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, and reproduced in the Convention. Washington.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sachs, Emanie (1928). The Terrible Siren. Harper & Brothers.

- Safronoff, Cindy Peyser (2015). Crossing Swords: Mary Baker Eddy vs Victoria Clafin Woodhull and the Battle for the Soul of Marriage – The Untold Story of America's Nineteenth-Century Culture War. Seattle: this one thing.

- Schrupp, Antje (2002). Das Aufsehen erregende Leben der Victoria Woodhull (in German). Helmer.

- Shone, Steve J. (2019). "The Originality and Political Philosophy of Victoria C. Woodhull". Women of Liberty. Studies in Critical Social Sciences. Vol. 135. Brill Publishers. pp. 79–130. doi:10.1163/9789004393226_005. ISBN 978-90-04-39045-4. S2CID 211977507.

- The Staff of the Historian's Office and National Portrait Gallery (1972). If Elected...' Unsuccessful candidates for the presidency 1796–1968. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Offices.

- Stern, Madeleine B. (1974). The Victoria Woodhull reader. Weston. ISBN 978-0-87730-009-0.

Primary sources

[edit]- Woodhull, Victoria C. (2005) [1874]. Free Lover: Sex, Marriage and Eugenics in the Early Speeches of Victoria Woodhull. Seattle. ISBN 1-58742-050-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). Four of her most important early and radical speeches on sexuality as facsimiles of the original published versions. Includes: "The Principle of Social Freedom" (1872), "The Scare-crows of Sexual Slavery" (1873), "The Elixir of Life" (1873), and "Tried as by Fire" (1873–74). - Woodhull, Victoria C. (2005) [1893]. Lady Eugenist: Feminist Eugenics in the Speeches and Writings of Victoria Woodhull. Seattle. ISBN 1-58742-040-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). Seven of her most important speeches and writings on eugenics. Five are facsimiles of the original, published versions. Includes: "Children – Their Rights and Privileges" (1871), "The Garden of Eden" (1875, publ. 1890), "Stirpiculture" (1888), "Humanitarian Government" (1890), "The Rapid Multiplication of the Unfit" (1891), and "The Scientific Propagation of the Human Race" (1893) - Woodhull, Victoria C. (1870). Constitutional equality the logical result of the XIV and XV Amendments, which not only declare who are citizens, but also define their rights, one of which is the right to vote without regard to sex. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Woodhull, Victoria C. (1871). The Origin, Tendencies and Principles of Government, or, A Review of the Rise and Fall of Nations from Early Historic Time to the Present. New York: Woodhull, Claflin & Company: New York: Woodhull, Claflin & Co.

- Woodhull, Victoria C. (1871). Speech of Victoria C. Woodhull on the great political issue of constitutional equality, delivered in Lincoln Hall, Washington, Cooper Institute, New York Academy of Music, Brooklyn, Academy of Music, Philadelphia, Opera House, Syracuse: together with her secession speech delivered at Apollo Hall.

- Woodhull, Victoria C. Martin (1891). The Rapid Multiplication of the Unfit. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit]- Weston, Victoria. America's Victoria, Remembering Victoria Woodhull features Gloria Steinem and actress Kate Capshaw. Zoie Films Productions (1998). PBS and Canadian Broadcasts. America's Victoria: Remembering Victoria Woodhull (1998) (TV) at IMDb

- Woodhull on harvard.edu

- Biographical timeline Archived October 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Victoria Woodhull, Anthony Comstock, and Conflict over Sex in the United States in the 1870s, The Journal of American History, 87, No. 2, September 2000, by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, pp. 403–434

- Athey, Stephanie (2000). "Eugenic Feminisms in Late Nineteenth-Century America: Reading Race in Victoria Woodhull, Frances Willard, Anna Julia Cooper and Ida B. Wells". Genders Journal (31). OCLC 1110322243. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Additional pages archived on index: Genders archives at colorado.edu.

- "Legal Contender... Victoria C. Woodhull: First Woman to Run for President", The Women's Quarterly (Fall 1988)

- Victoria Woodhull, Topics in Chronicling America, Library of Congress

- "A lecture on constitutional equality," delivered at Lincoln hall, Washington, D.C., Thursday, February 16, 1871, by Victoria C. Woodhul, American Memory, Library of Congress

- A history of the national woman's rights movement, for twenty years, with the proceedings of the decade meeting held at Apollo hall, October 20, 1870, from 1850 to 1870, with an appendix containing the history of the movement during the winter of 1871, in the national capitol, comp. by Paulina W. Davis., American Memory, Library of Congress

- "And the truth shall make you free." A speech on the principles of social freedom, delivered in Steinway hall, Nov. 20, 1871, by Victoria C. Woodhull, American Memory, Library of Congress

- "Tried as by Fire" at the University of South Carolina Library's Digital Collections Page

- Movie review: "America's Victoria, Remembering Victoria Woodhull", The American Journal of History

- http://www.victoria-woodhull.com/

- 1838 births

- 1927 deaths

- 19th-century American businesswomen

- 19th-century American businesspeople

- 19th-century American newspaper editors

- 19th-century American newspaper founders

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- 19th-century American women writers

- American abolitionists

- American anti-abortion activists

- American eugenicists

- American expatriates in England

- American spiritualists

- American socialists

- American socialist feminists

- American stockbrokers

- American suffragists

- American women company founders

- American women non-fiction writers

- American women's rights activists

- Candidates in the 1872 United States presidential election

- Candidates in the 1884 United States presidential election

- Candidates in the 1892 United States presidential election

- Claflin family

- Female candidates for President of the United States

- Free love advocates

- Members of the International Workingmen's Association

- People from Licking County, Ohio

- People from Wychavon (district)

- Proponents of Christian feminism

- Sex-positive feminists

- Women in Ohio politics

- American women newspaper editors

- Women of the Victorian era

- Women stockbrokers

- Woodhull family