Alley

An alley or alleyway is a narrow lane, path, or passageway, often reserved for pedestrians, which usually runs between, behind, or within buildings in the older parts of towns and cities. It is also a rear access or service road (back lane), or a path, walk, or avenue (French allée) in a park or garden.[1]

A covered alley or passageway, often with shops, may be called an arcade. The origin of the word alley is late Middle English, from Old French: alee "walking or passage", from aller "to go", from Latin: ambulare "to walk".[2]

Definition

[edit]

The word alley is used in two main ways:

- It can refer to a narrow, usually paved, pedestrian path, often between the walls of buildings in towns and cities. This type is usually short and straight, and on steep ground can consist partially or entirely of steps.

- It also describes a very narrow, urban street, or lane, usually paved, which may be used by slow-moving local traffic, though more pedestrian-friendly than a regular street. There are two versions of this kind of alley:

- A rear access or service road (back lane), which can also sometimes act as part a secondary vehicular network. Many Americans and Canadians think of an alley in these terms first.

- A narrow street running between houses or businesses. This type of alley is found in the older parts of many cities, including American cities like Philadelphia and Boston (see Elfreth's Alley, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). Many are open to local traffic.

In landscaping, an allée or avenue is traditionally a straight route with a line of trees or large shrubs running along each side. In most cases, the trees planted in an avenue will be all of the same species or cultivar, so as to give uniform appearance along the full length of the avenue. The French term allée is used for avenues planted in parks and landscape gardens, as well as boulevards such as the Grand Allée in Quebec City, Canada, and Karl-Marx-Allee in Berlin.

In older cities and towns in Europe, alleys are often what is left of a medieval street network, or a right of way or ancient footpath. Similar paths also exist in some older North American towns and cities. In some older urban development in North America lanes at the rear of houses, to allow for deliveries and garbage collection, are called alleys. Alleys and ginnels were also the product of the 1875 Public Health Act in the United Kingdom, where usually alleys run along the back of streets of terraced houses, with ginnels connecting them to the street every fifth house.[citation needed] Alleys may be paved, or unpaved, and a blind alley is a cul-de-sac. Modern urban developments may also provide a service road to allow for waste collection, or rear access for fire engines and parking.

Steps and stairs

[edit]Because of geography, steps (stairs) are the predominant form of alley in hilly cities and towns. This includes Quebec City in Canada and in the United States Pittsburgh (see Steps of Pittsburgh), Cincinnati (see Steps of Cincinnati), Minneapolis, Seattle,[3] and San Francisco[4] as well as Hong Kong,[5] Genoa and Rome.[6]

Covered passages

[edit]

Arcades are another kind of covered passageway and the simplest kind are no more than alleys to which a glass roof was added later. Early examples of a shopping arcades include: Palais Royal in Paris (opened in 1784); Passage de Feydeau in Paris (opened in 1791).[7] Most arcades differ from alleys in that they are architectural structures built with a commercial purpose and are a form of shopping mall. All the same alleys have for long been associated with various types of businesses, especially pubs and coffee houses. Bazaars and Souqs are an early form of arcade found in Asia and North Africa.

Some alleys are roofed because they are within buildings, such as the traboules of Lyon, or when they are a pedestrian passage through railway embankments in Britain. The latter follow the line of rights-of way that existed before the railway was built.

The Burlington Arcade (1819) was one of London's earliest covered shopping arcades.[8] It was the successful prototype for larger glazed shopping arcades, beginning with the Saint-Hubert Gallery (1847) in Brussels and The Passage (1848) in St Petersburg, the first of Europe's grand arcades, to the Galleria Umberto I (1891) in Naples, the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan (1867), and the Block Arcade, Melbourne, Australia (1893).

By country

[edit]Asia

[edit]

Alleyways are an understudied urban form historically shared by most Asian cities. They provide a setting for much everyday urban life and place-based identity, the examination of which can shed new light on the traditional idea of a global city and contributes to a renewed conception of metropolization as a highly localized process.[9]

China

[edit]

Hutongs (simplified Chinese: 胡同; traditional Chinese: 衚衕; pinyin: hútòng; Wade–Giles: hu-t'ung) are a type of narrow streets or alleys, commonly associated with northern Chinese cities, most prominently Beijing.

In Beijing, hutongs are alleys formed by lines of siheyuan, traditional courtyard residences.[10] Many neighbourhoods were formed by joining one siheyuan to another to form a hutong, and then joining one hutong to another. The word hutong is also used to refer to such neighbourhoods. During China's dynastic period, emperors planned the city of Beijing and arranged the residential areas according to the social classes of the Zhou dynasty (1027–256 BC). The term "hutong" appeared first during the Yuan dynasty, and is a term of Mongolian origin meaning "town".[11]

At the turn of the 20th century, the Qing court was disintegrating as China's dynastic era came to an end. The traditional arrangement of hutongs was also affected. Many new hutongs, built haphazardly and with no apparent plan, began to appear on the outskirts of the old city, while the old ones lost their former neat appearance.

Following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, many of the old hutongs of Beijing disappeared, replaced by wide boulevards and high rises. Many residents left the lanes where their families lived for generations for apartment buildings with modern amenities. In Xicheng District, for example, nearly 200 hutongs out of the 820 it held in 1949 have disappeared. However, many of Beijing's ancient hutongs still stand, and a number of them have been designated protected areas. Many hutongs, some several hundred years old, in the vicinity of the Bell Tower and Drum Tower and Shichahai Lake are preserved amongst recreated contemporary two- and three-storey versions.[12][13]

Hutongs represent an important cultural element of the city of Beijing and the hutongs are residential neighborhoods which still form the heart of Old Beijing. While most Beijing hutongs are straight, Jiudaowan (九道弯, literally "Nine Turns") Hutong turns nineteen times. At its narrowest section, Qianshi Hutong near Qianmen (Front Gate) is only 40 centimeters (16 inches) wide.[14]

The Shanghai longtang is loosely equivalent to the hutong of Beijing. A longtang (弄堂 lòngtáng, Shanghainese: longdang) is a laneway in Shanghai and, by extension, a community centred on a laneway or several interconnected laneways. On its own long (traditional Chinese 衖 or 弄, simplified Chinese 弄) is a Chinese term for "alley" or "lane", which is often left untranslated in Chinese addresses, but may also be translated as "lane", and "tang" is a parlor or hallway.[15] It is sometimes called lilong (里弄); the latter name incorporates the -li suffix often used in the name of residential developments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As with the term hutong, the Shanghai longdang can either refers to the lanes that the houses face onto, or a group of houses connected by the lane.[16][17][18][19]

Japan

[edit]

Shinjuku Golden Gai (新宿ゴールデン街) is a small area of Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan,[20] famous both as an area of architectural interest and for its nightlife. It is composed of a network of six narrow alleys, connected by even narrower passageways which are just about wide enough for a single person to pass through. Over 200 tiny shanty-style bars, clubs and eateries are squeezed into this area.[21]

Its architectural importance is that it provides a view into the relatively recent past of Tokyo, when large parts of the city resembled present-day Golden Gai, particularly in terms of the extremely narrow lanes and the tiny two-storey buildings. Nowadays, most of the surrounding area has been redeveloped. Typically, the buildings are just a few feet wide and are built so close to the ones next door that they nearly touch. Most are two-storey, having a small bar at street level and either another bar or a tiny flat upstairs, reached by a steep set of stairs. None of the bars are very large; some are so small that they can only fit five or so customers at one time.[20] The buildings are generally ramshackle, and the alleys are dimly lit, giving the area a very scruffy and run-down appearance. However, Golden Gai is not a cheap place to drink, and the clientele that it attracts is generally well off.

Golden Gai is well known yokocho and meeting place for musicians, artists, directors, writers, academics and actors, including many celebrities. Many of the bars only welcome regular customers, who initially should be introduced by an existing patron, although many others welcome non-regulars, some even making efforts to attract overseas tourists by displaying signs and price lists in English.[20] Golden Gai was known for prostitution before 1958, when prostitution became illegal. Since then it has developed as a drinking area, and at least some of the bars can trace their origins back to the 1960s.

Apart from drinking alleys (drinking yokocho), shotengai and yokocho shotengais, there are the ordinary alleyways, the rojis which seem exist in all parts of the Japanese urban landscape. The roji which was once part of people's personal spatial sphere and everyday life has been transformed by diverse and competing interests. Marginalised through the emergence of new forms of housing and public spaces, re-appropriated by different fields, and re-invented by the contemporary urban design discourse, the social meaning attached to the roji is being re-interpreted by individuals, subcultures and new social movements. Thus, their existence is in danger.[22]

Vietnam

[edit]Hẻm/Ngõ alleyways are a Vietnamese vernacular urban planning typology, common in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi.[23][24]

Australia

[edit]

Sydney features a series of laneways in its central business district that have been used to provide off-street vehicular access to city buildings and alternative pedestrian routes through city blocks, in addition to featuring street art, cafes, restaurants, bars and retail outlets.[25] The Rocks has the most prominent and historical laneways in Sydney, which date to the 19th century.[26] Forgotten Songs is a popular attraction situated in Angel Place.[27] Chinatown features a number of lanes and alleyways.[28] In suburban Sydney, several alleyways or laneways exist between residential lots that provide pedestrians a shortcut passage to nearby facilities on adjacent roads.[29]

The Melbourne central business district in is home to many lanes and arcades.[30][31] These laneways date mostly from the Victorian era, and are a popular cultural attraction for their cafes, bars and street art. The city's oldest laneways are a result of Melbourne's original urban plan, the 1837 Hoddle Grid, and were designed as access routes to service properties fronting the CBD's major thoroughfares.[32] St Jerome's Laneway Festival, often referred to simply as Laneway, is a popular music festival that began in 2004 in Melbourne's laneways.

The lanes and arcades of Perth, Western Australia are together becoming culturally significant to the city.[33][34] In 2007 modification to Liquor Licensing Regulations in Western Australia opened up the opportunities for small bars.[35] This was followed in August 2008 by the City of Perth formally adopting a laneways enhancement strategy, "Forgotten Spaces – Revitalising Perth's Laneways".[36]

Europe

[edit]Belgium

[edit]In Belgium the equivalent term is gang (Dutch) or impasse (French). Brussels had over 100 gangen/impasses, built to provide pedestrian access to cheap housing in the middle of blocks of buildings, and often containing a communal water tap. Several lead off Rue Haute/Hoogstraat. Since 1858, many have been demolished as part of slum clearance programmes, but about 70 still exist.[37] Some have been gentrified, for example the Rue de la Cigogne/Ooievaarstraat.

Germany

[edit]

The old town of Lübeck has over 100 Gänge, particularly leading off the streets Engelswisch, Engelsgrube and Glockengießerstraße, as well as around the cathedral. Some are very low as well as narrow, and others open into more spacious courtyards (Höfe). Spreuerhofstraße is the world's narrowest street, found in the city of Reutlingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.[38] It ranges from 31 centimetres (12.2 in) at its narrowest to 50 centimetres (19.7 in) at its widest.[39] The lane was built in 1727 during the reconstruction efforts after the area was completely destroyed in the massive citywide fire of 1726 and is officially listed in the Land-Registry Office as City Street Number 77.[38][40] Lintgasse is an alley (German: Gasse) in the Old town of Cologne, Germany between the two squares of Alter Markt and Fischmarkt. It is a pedestrian zone and though only some 130 metres long, is nevertheless famous for its medieval history. The Lintgasse was first mentioned in the 12th century as in Lintgazzin, which may be derived from basketmakers who wove fish baskets out of Linden tree barks. These craftsmen were called Lindslizer, meaning Linden splitter. During the Middle Ages, the area was also known as platēa subri or platēa suberis, meaning street of Quercus suber, the cork oak tree. Lintgasse 8 to 14 used to be homes of medieval knights as still can be seen by signs like Zum Huynen, Zum Ritter or Zum Gir. During the 19th-century the Lintgasse was called Stink-Linkgaß, a because of its poor air quality.[41]

France

[edit]Lyon's traboules

[edit]

The traboules of Lyon are passageways that cut through a house or, in some cases, a whole city block, linking one street with another. They are distinct from most other alleys in that they are mainly enclosed within buildings and may include staircases. While they are found in other French cities including Villefranche-sur-Saône, Mâcon, Chambéry, Saint-Étienne, Louhans, Chalon sur Saône and Vienne (Isère), Lyon has many more; in all there are about 500.

The word traboule comes from the Latin trans ambulare, meaning "to cross", and the first of them were possibly built as early as the 4th century. As the Roman Empire disintegrated, the residents of early Lyon—Lugdunum, the capital of Roman Gaul—were forced to move from the Fourvière hill to the banks of the river Saône when their aqueducts began to fail. The traboules grew up alongside their new homes, linking the streets that run parallel to the river Saône and going down to the river itself. For centuries they were used by people to fetch water from the river and then by craftsmen and traders to transport their goods. By the 18th century they were invaluable to what had become the city's defining industry, textiles, especially silk.[42]

Nowadays, traboules are tourist attractions, and many are free and open to the public. Most traboules are on private property, serving as entrances to local apartments.

Italy

[edit]The common Italian word for an alley is vicolo.[43]

Venice

[edit]Venice is largely a traffic free city and there is, in addition to the canals, a maze of around 3000 lanes and alleys called calli (which means narrow). Smaller ones are callètte or callesèlle, while larger ones are calli large. Their width varies from just over 50 centimetres (19.7 in) to 5–6 metres (196.9–236.2 in). The narrowest is Calletta Varisco, which just 53 centimetres (20.9 in); Calle Stretta is 65 centimetres (25.6 in) wide and Calle Ca' Zusto 68 centimetres (26.8 in). The main ones are also called salizada and wider calli, where trade proliferates, are called riga, while blind calli, used only by residents to reach their homes, are ramo.[44]

Netherlands

[edit]Cities such as Amsterdam and Groningen have numerous gangen or stegen. They often run between the major streets, roughly parallel to each other but not at right angles to the streets, following the old field boundaries and ditches.[45]

Sweden

[edit]

Gränd is Swedish for an alley and there are numerous gränder, or alleys in Gamla stan, The Old Town, of Stockholm, Sweden. The town dates back to the 13th century, with medieval alleyways, cobbled streets, and historic buildings. North German architecture has had a strong influence in the Old Town's buildings. Some of Stockholm's alleys are very narrow pedestrian footpaths, while others are very narrow, cobbled streets, or lanes open to slow moving traffic. Mårten Trotzigs gränd ("Alley of Mårten Trotzig") runs from Västerlånggatan and Järntorget up to Prästgatan and Tyska Stallplan, and part of it consists of 36 steps. At its narrowest the alley is a mere 90 cm (35 inches) wide, making it the narrowest street in Stockholm.[46] The alley is named after the merchant and burgher Mårten Trotzig (1559–1617), who, born in Wittenberg,[46] emigrated to Stockholm in 1581, and bought properties in the alley in 1597 and 1599, also opening a shop there. According to sources from the late 16th century, he was dealing in first iron and later copper, by 1595 had sworn his burgher oath, and was later to become one of the richest merchants in Stockholm.[47]

Possibly referred to as Trångsund ("Narrow strait") before Mårten Trotzig gave his name to the alley, it is mentioned in 1544 as Tronge trappe grenden ("Narrow Alley Stairs"). In 1608 it is referred to Trappegrenden ("The Stairs Alley"), but a map dated 1733 calls it Trotz gränd. Closed off in the mid 19th century, not to be reopened until 1945, its present name was officially sanctioned by the city in 1949.[47]

The "List of streets and squares in Gamla stan" provides links to many pages that describe other alleys in the oldest part of Stockholm; e.g. Kolmätargränd (Coal Meter's Alley); Skeppar Karls Gränd (Skipper Karl's Alley); Skeppar Olofs Gränd (Skipper Olof's Alley); and Helga Lekamens Gränd (Alley of the Holy Body).

United Kingdom

[edit]London

[edit]

London has numerous historical alleys, especially, but not exclusively, in its centre; this includes The City, Covent Garden, Holborn, Clerkenwell, Westminster and Bloomsbury amongst others.

An alley in London can also be called a passage, court, place, lane, and less commonly path, arcade, walk, steps, yard, terrace, and close.[48][49] While both a court and close are usually defined as blind alleys, or cul-de-sacs, several in London are throughways, for example Cavendish Court, a narrow passage leading from Houndsditch into Devonshire Square, and Angel Court, which links King Street and Pall Mall.[49] Bartholomew Close is a narrow winding lane which can be called an alley by virtue of its narrowness, and because through-access requires the use of passages and courts between Little Britain, and Long Lane and Aldersgate Street.[50]

In an old neighbourhood of the City of London, Exchange Alley or Change Alley is a narrow alleyway connecting shops and coffeehouses.[51] It served as a convenient shortcut from the Royal Exchange on Cornhill to the Post Office on Lombard Street and remains as one of a number of alleys linking the two streets. The coffeehouses[52] of Exchange Alley, especially Jonathan's and Garraway's, became an early venue for the lively trading of shares and commodities. These activities were the progenitor of the modern London Stock Exchange.

Lombard Street and Change Alley had been the open-air meeting place of London's mercantile community before Thomas Gresham founded the Royal Exchange in 1565.[51] In 1698, John Castaing began publishing the prices of stocks and commodities in Jonathan's Coffeehouse, providing the first evidence of systematic exchange of securities in London.

Change Alley was the site of some noteworthy events in England's financial history, including the South Sea Bubble from 1711 to 1720 and the panic of 1745.[53]

In 1761 a club of 150 brokers and jobbers was formed to trade stocks. The club built its own building in nearby Sweeting's Alley in 1773, dubbed the "New Jonathan's", later renamed the Stock Exchange.[54]

West of the City there are a number of alleys just north of Trafalgar Square, including Brydges Place which is situated right next to the Coliseum Theatre and just 15 inches wide at its narrowest point, only one person can walk down it at a time. It is the narrowest alley in London and runs for 200 yards (180 m), connecting St Martin's Lane with Bedfordbury in Covent Garden.[55]

Close by is another very narrow passage, Lazenby Court, which runs from Rose Street to Floral Street down the side of the Lamb and Flag pub; in order to pass people must turn slightly sideways. The Lamb & Flag in Rose Street has a reputation as the oldest pub in the area,[56] though records are not clear. The first mention of a pub on the site is 1772.[57] The Lazenby Court was the scene of an attack on the famous poet and playwright John Dryden in 1679 by thugs hired by John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester,[58] with whom he had a long-standing conflict.[59]

In the same neighbourhood Cecil Court has an entirely different character than the two previous alleys, and is a spacious pedestrian street with Victorian shop-frontages that links Charing Cross Road with St Martin's Lane, and it is sometimes used as a location by film companies.[60][61]

One of the older thoroughfares in Covent Garden, Cecil Court dates back to the end of the 17th century. A tradesman's route at its inception, it later acquired the nickname Flicker Alley because of the concentration of early film companies in the Court.[62] The first film-related company arrived in Cecil Court in 1897, a year after the first demonstration of moving pictures in the United Kingdom and a decade before London's first purpose-built cinema opened its doors. Since the 1930s it has been known as the new Booksellers' Row as it is home to nearly twenty antiquarian and second-hand independent bookshops.

It was the temporary home of an eight-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart while he was touring Europe in 1764. For almost four months the Mozart family lodged with barber John Couzin.[63] According to some modern authorities, Mozart composed his first symphony while a resident of Cecil Court.[64]

North of the centre of London, Camden Passage is a pedestrian passage off Upper Street in the London Borough of Islington, famous because of its many antiques shops, and an antique market on Wednesdays and Saturday mornings. It was built, as an alley, along the backs of houses on Upper Street, then Islington High Street, in 1767.[65]

Southern England

[edit]- In East Sussex, West Sussex and Surrey, twitten is used, for "a narrow path between two walls or hedges". It is still in official use in some towns including Lewes,[66] Brighton, and Cuckfield.[67][68] "Loughton also has twittens, the only Essex example of use of the word and an indication of a very old street pattern"; Loughton also has a track known locally as The Widden, a variant of twitten.[69] In north-west Essex and east Hertfordshire twichell is common. In other parts of Essex, alley or path is used.

- In the city of Brighton and Hove (in East Sussex), The Lanes is a collection of narrow lanes famous for their small shops (including several antique shops) and narrow alleyways. The area was part of the original settlement of Brighthelmstone, but The Lanes were built up during the late 18th century and were fully laid out by 1792.[70]

West of England

[edit]- In Plymouth, Devon an alley is an ope.[71]

- More generally in Devon any narrow public way which is less commodious than a lane may be called a drangway (from drang, as a dialectal variation of throng); typically it will be used on horseback or on foot with or without animals, but may also be for occasional use with vehicles.[72] The word, according to David Crystal, is also used throughout the West of England, Wiltshire, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, as well as Wales.[73]

Midlands and East Anglia

[edit]- In Birmingham an entry runs between houses or through terraced houses, while a gully runs behind houses.[74]

- In Derbyshire and Leicestershire the word jitty or gitties is often found[75] and gulley is a term used in the Black Country.[76]

- In Nottinghamshire, twichell is common (See East Midlands English).

- In Shropshire (especially Shrewsbury) they are called shuts.[77]

Northern England

[edit]

- The Snickelways of York, in York, Yorkshire, often misspelt snickleways, are a collection of small streets, footpaths, or lanes between buildings, not wide enough for a vehicle to pass down, and usually public rights of way. York has many such paths, mostly mediaeval, though there are some modern paths as well. They have names like any other city street, often quirky names such as Mad Alice Lane, Nether Hornpot Lane and even Finkle Street (formerly Mucky Peg Lane). The word snickelway was coined by local author Mark W. Jones in 1983 in his book A Walk Around the Snickelways of York, and is a portmanteau, a blend of the words snicket, meaning a passageway between walls or fences, ginnel, a narrow passageway between or through buildings, and alleyway, a narrow street or lane. Although a neologism, the word quickly became part of the local vocabulary, and has even been used in official council documents.[78]

- In Whitby, North Yorkshire ghauts.[79]

- In Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, Goole and Hull, East Riding of Yorkshire other terms in use are cuttings, 8-foots, 10-foots, and snicket.

- In North Yorkshire and County Durham, as in Scotland, an alley can be a wynd. There is a "Bull Wynd" in Darlington, County Durham and Lombards Wynd in Richmond, North Yorkshire.[80]

- In Durham City narrow passages are also known as vennels. Several of these still exist and provide steep shortcuts between the major streets.[citation needed]

- In north-east England, including Bishop Auckland, County Durham; Durham; Hexham, Northumberland; Morpeth, Northumberland; Whitburn, South Tyneside; and Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland, alleys can be called chares. The chares and much of the layout of Newcastle's Quayside date from medieval times. At one point, there were 20 chares in Newcastle. After the great fire of Newcastle and Gateshead in 1854, a number of the chares were permanently removed although many remain in existence today. Chares also are still present in the higher parts of the city centre. According to "Quayside and the Chares"[81] by Jack and John Leslie, chares reflected their name or residents. "Names might change over the years, including Armourer's Chare which become Colvin's Chare". Originally inhabited by wealthy merchants, the chares became slums as they were deserted due to their "dark, cramped conditions". The chares were infamous for their insanitary conditions – typhus was "epidemic" and there were three cholera outbreaks in 1831–2, 1848–9 and finally in 1853 (which killed over 1,500 people).

- In Manchester and Oldham, Greater Manchester, as well as Sheffield, Leeds, Preston and other parts of Yorkshire, jennel, which may be spelt gennel or ginnel, is common.[82] In some cases, ginnel may be used to describe a covered or roofed passage, as distinct from an open alley. In the Yorkshire Historical Dictionary, the entry for the word ginnel begins, "Many dialect words have been lost in recent times but 'ginnel' survives in good health, acceptable in polite conversation and even in newspaper articles."[83]

- In Liverpool, Merseyside, the terms entry, jigger or snicket are more common. Entry is also used in some parts of Lancashire and Manchester, though not in South Manchester. This usually refers to a walkway between two adjoining terraced houses, which leads from the street to the rear yard or garden. The term entry is used for an alley in Belfast, Northern Ireland (see The Belfast Entries).

Scotland and Northern Ireland

[edit]

In Scotland and Northern Ireland the Scots terms close, wynd, pend and vennel are general in most towns and cities. The term close has an unvoiced "s" as in sad. The Scottish author Ian Rankin's novel Fleshmarket Close was retitled Fleshmarket Alley for the American market. Close is the generic Scots term for alleyways, although they may be individually named closes, entries, courts and wynds. Originally, a close was private property, hence gated and closed to the public.

A wynd is typically a narrow lane between houses, an open throughway, usually wide enough for a horse and cart. The word derives from Old Norse venda, implying a turning off a main street, without implying that it is curved.[84] In fact, most wynds are straight. In many places wynds link streets at different heights and thus are mostly thought of as being ways up or down hills.

A pend is a passageway that passes through a building, often from a street through to a courtyard, and typically designed for vehicular rather than exclusively pedestrian access.[85] A pend is distinct from a vennel or a close, as it has rooms directly above it, whereas vennels and closes are not covered over.

A vennel is a passageway between the gables of two buildings which can in effect be a minor street in Scotland and the north east of England, particularly in the old centre of Durham. In Scotland, the term originated in royal burghs created in the twelfth century, the word deriving from the Old French word venelle meaning "alley" or "lane". Unlike a tenement entry to private property, known as a close, a vennel was a public way leading from a typical high street to the open ground beyond the burgage plots.[86] The Latin form is venella.

North Africa

[edit]

A medina quarter (Arabic: المدينة القديمة al-madīnah al-qadīmah "the old city") is a distinct city section found in many North African cities. The medina is typically walled, contains many narrow and maze-like streets.[87] The word "medina" (Arabic: مدينة madīnah) itself simply means "city" or "town" in modern Arabic.

Because of the very narrow streets, medinas are generally free from car traffic, and in some cases even motorcycle and bicycle traffic. The streets can be less than a metre wide. This makes them unique among highly populated urban centres. The Medina of Fes, Morocco or Fes el Bali, is considered one of the largest car-free urban areas in the world.[88]

North America

[edit]Alleys in North America are primarily used as service lanes. They provide a space for utility poles, fire escapes, garage access, delivery loading zones, and garbage bin pickup.

Some historic alleys are found in older American and Canadian cities, like New York City, Philadelphia, Charleston, South Carolina, Boston, Annapolis, New Castle, Delaware, Quebec City, St John's, Newfoundland,[89] and Victoria, British Columbia.

Canada

[edit]Quebec City

[edit]Québec City was originally built on the riverside bluff Cap Diamant in the 17th century, and throughout Quebec City there are strategically placed public stairways that link the bluff to the lower parts of the city.[90] The Upper City is the site of Old Québec's most significant historical sites, including 17th- and 18th-century chapels, the Citadel and the city ramparts. The Breakneck Stairs or Breakneck Steps (French: Escalier casse-cou), Quebec City's oldest stairway, were built in 1635. Originally called escalier Champlain "Champlain Stairs", escalier du Quêteux "Beggars' Stairs", or escalier de la Basse-Ville "Lower Town Stairs", they were given their current name in the mid-19th century, because of their steepness. The stairs have been restored several times, including an 1889 renovation by Charles Baillargé.[91]

Victoria

[edit]

Fan Tan Alley is an alley in Victoria, British Columbia's Chinatown. It was originally a gambling district with restaurants, shops, and opium dens. Today it is a tourist destination with many small shops including a barber shop, art gallery, Chinese cafe and apartments. It may well be the narrowest street in Canada. At its narrowest point it is only 0.9 metres (35 in) wide.[92] Waddington Alley is another interesting alley in Victoria and the only street in that city still paved with wood blocks, an early pavement common in the downtown core. Other heritage features are buildings more than a century old lining the alley and a rare metal carriage curb that edges the sidewalk on the southern end.[93]

Vancouver

[edit]Nearly all blocks in Vancouver were designed with an alleyway, as the majority of homes do not have front driveways. Alleyways are, therefore, the way for home owners to access their garage and to also place their garbage for collection.[citation needed] Commercial laneway typically prohibit stopping except for delivery vehicles.[citation needed]

United States

[edit]In the United States alleys exist in both older commercial and residential areas, for both service purposes and automobile access. In residential areas, particularly in those that were built before 1950, alleys provide rear access to property where a garage was located, or where waste could be collected by service vehicles. A benefit of this was the location of these activities to the rear, less public side of a dwelling. Such alleys are generally roughly paved, but some may be dirt. Beginning in the late 20th century, they were seldom included in plans for new housing developments.[citation needed]

Annapolis, Maryland

[edit]When Annapolis, Maryland, was established as a city at the beginning of the 18th century,[94] the streets were established in circles. That encouraged the creation of shortcuts, which over time became paved alleys. Some ten of these survive, and the city has recently worked on making them more attractive.[95]

Austin, Texas

[edit]Several residential neighborhoods in Austin, Texas, have comprehensive alley systems. These include Hyde Park, Rosedale, and areas northwest of the Austin State Hospital. There are also numerous alleys downtown, particularly in the 6th Street district, where bars and restaurants place their garbage for collection.[citation needed]

Boston

[edit]

In the Beacon Hill district of Boston, Massachusetts, Acorn Street, a narrow cobbled lane with row houses, is one of Boston's more attractive and historic alleys. Many of the alleys in the Back Bay and South End area are numbered (e.g. "Public Alley 438").[96]

Charleston, South Carolina

[edit]In the French Quarter of Charleston's historic district, Philadelphia Alley (c. 1766), originally named "Cow Alley", is one of several picturesque alleys. In 1810 William Johnson gave it the name of "Philadelphia Alley", although locals call the "elegantly landscaped thoroughfare" "Dueler's Alley".[97] Starting on East Bay Street, Stolls Alley is just seventeen bricks wide at its start, and named for Justinus Stoll, an 18th-century blacksmith.[98] For three hundred years, another of Charleston's narrow lanes, Lodge Alley, served a commercial purpose. Originally, French Huguenot merchants built homes on it, along with warehouses to store supplies for their ships. Just 10 feet (3.0 m) wide, this alley was a useful means of access to Charleston's waterways.[99] Today it leads to East Bay Street's many restaurants.

Chicago, Illinois

[edit]Chicago has the largest network of alleys in the United States, with more than 1,900 miles of alleyways within city limits, also ranking as one of the largest systems in the world. Alleys have been an integral part of Chicago's urban landscape since the city was first incorporated, and have grown in complexity since the 1830s, with many of the city's elevated "L" transit rail lines still running overhead today.[100][101] Although initially considered seedy and uncivilized, the utilitarian nature of alleys has afforded Chicago the ability to keep main roads and thoroughfares clear of trash, unlike other large cities in the country, while also providing additional space for residential and commercial car parking, as well as maintaining accessible electrical and plumbing utilities, both above and below ground. In 2006, the Chicago Department of Transportation began implementing the "Green Alley" program, an ongoing effort to replace hardtop alley surfaces with permeable pavers and better grading to more quickly absorb storm water runoff into the groundwater below, reducing stress on the city's infrastructure, as well as introducing lighter colored "high albedo" pavement to reflect sunlight and reduce urban heat island effect.[102]

Cincinnati, Ohio

[edit]Cincinnati is a city of hills.[103] Before the advent of the automobile a system of stairway alleys provided pedestrians important and convenient access to and from their hill top homes. At the height of their use in the 19th century, over 30 miles (48 km) of hill side steps once connected the neighborhoods of Cincinnati to each other.[104] The first steps were installed by residents of Mount Auburn in the 1830s in order to gain easier access to Findlay Market in Over-the-Rhine.[105] In recent years many steps have fallen into disrepair but there is a movement now to rehabilitate them.[106]

New Castle, Delaware

[edit]Another early settled American city, New Castle has a number of interesting alleys, some of which are footpaths and others narrow, sometimes cobbled, lanes open to traffic.[107]

New York City

[edit]

New York City's Manhattan is unusual in that it has very few alleys, since the Commissioner's Plan of 1811 did not include rear service alleys when it created Manhattan's grid. The exclusion of alleys has been criticized as a flaw in the plan, since services such as garbage pickup cannot be provided out of sight of the public, although other commentators feel that the lack of alleys is a benefit to the quality of life of the city.[108] Since there are so few alleys in New York, film location shooting requiring alleys tend to be concentrated in Cortlandt Alley, located between Canal and Franklin Streets in the blocks between Broadway and Lafayette Street in the TriBeCa neighborhood of lower Manhattan.[109]

Two notable alleys in the Greenwich Village neighborhood in Manhattan are MacDougal Alley and Washington Mews.[110] The latter is a blind alley or cul-de-sac. Greenwich Village also has a number of private alleys that lead to back houses, which can only be accessed by residents, including Grove Court,[111] Patchin Place and Milligan Place, all blind alleys. Patchin Place is notable for the writers who lived there.[112] In the Brooklyn Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, Grace Court Alley is another converted mews,[113] as is Dennett Place in the Carroll Gardens neighborhood.[114] The former is a cul-de-sac.

Shubert Alley is a 300-foot (91 m) long pedestrian alley at the heart of the Broadway theater district of New York City. The alley was originally created as a fire exit between the Shubert Theatre on West 45th Street and the Booth Theatre on West 44th Street, and the Astor Hotel to their east. Actors once gathered in the alley, hoping to attract the attention of the Shubert Brothers and get employment in their theatrical productions.[115] When the hotel was torn down, and replaced with One Astor Plaza (1515 Broadway), the apparent width of the alley increased, as the new building did not go all the way to the westernmost edge of the building lot. However, officially, Shubert Alley consists only of the space between the two theatres and the lot line.

Philadelphia

[edit]

The Old City and Society Hill neighborhoods of Philadelphia, the oldest parts of the city, include a number of alleys, notably Elfreth's Alley, which is called "Our nation's oldest residential street", dating from 1702.[116] As of 2012[update], there were 32 houses on the street, which were built between 1728 and 1836.[117]

There are numerous cobblestoned residential passages in Philadelphia, many no wider than a truck, and typically flanked with brick houses. A typical house on these alleys or lanes is called a Philadelphia "Trinity", named because it has three rooms, one to each floor, alluding to the Christian Trinity.[118] These alleys include Willings Alley, between S. 3rd and S. 4th Streets and Walnut and Spruce Streets.[119] Other streets in Philadelphia which fit the general description of an alley, but are not named "alley", include Cuthbert Street, Filbert Street, Phillips Street,[120] South American Street,[121] Sansom Walk,[122] St. James Place,[123] and numerous others.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

[edit]Steps, Pittsburgh's equivalent for an alley, have defined it for many visitors. Writing in 1937, war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote of the steps of Pittsburgh:

And then the steps. Oh Lord, the steps! I was told they actually had a Department of Steps. That isn't exactly true, although they do have an Inspector of Steps. But there are nearly 15 miles (24 km) of city-owned steps, going up mountainsides.[124]

The City of Pittsburgh maintains 712 sets of city-owned steps, some of which are shown as streets on maps.[125]

San Francisco, California

[edit]

In hilly San Francisco, California alleys often take the form of steps and it has several hundred public stairways.[126] Among the most famous is the stairway known as the Filbert steps, a continuation of Filbert Street.[127] The Filbert Street Steps descend the east slope of Telegraph Hill along the line where Filbert Street would be if the hill was not so steep. The stairway is bordered by greenery, that consists both backyards, and a border garden tended to and paid for by the residents of the "street", and runs down to an eastern stub of Filbert Street and the walkway through the plaza to The Embarcadero. Many houses in this residential neighborhood are accessible only from the steps.

Also in San Francisco, Belden Place is a narrow pedestrian alley, bordered by restaurants, in the Financial District, referred to as San Francisco's French Quarter for its historic ties to early French immigrants, and its popular contemporary French restaurants and institutions.[128] The area was home to San Francisco's first French settlers. Approximately 3,000, sponsored by the French government, arrived near the end of the Gold Rush in 1851.[129]

San Luis Obispo

[edit]Bubblegum Alley is a tourist attraction where people have left their finished bubblegum on the walls of an alley for decades. The walls have been cleaned multiple times only to have the gum rapidly reappear.

Seattle

[edit]There are over 600 publicly accessible stairways within Seattle, a city of hills, bluffs, and canyons.[130] For an example see Howe Street Stairs.

Green and revitalized alleys

[edit]

Numerous cities in the United States and Canada, such as Chicago,[131] Seattle,[132] Los Angeles,[133] Phoenix, Washington, D.C.,[134] and Montréal, have started reclaiming their alleys from garbage and crime by greening the service lanes, or back ways, that run behind some houses.[134][135] Chicago, Illinois has about 1,900 miles (3,100 km) of alleyways.[131] In 2006, the Chicago Department of Transportation started converting conventional alleys which were paved with asphalt into so called Green Alleys. This program, called the Green Alley Program, is supposed to enable easier water runoff, as the alleyways in Chicago are not connected directly to the sewer system. With this program, the water will be able to seep through semi-permeable concrete or asphalt in which a colony of fungi and bacteria will establish itself. The bacteria will help breakup oils before the water is absorbed into the ground. The lighter color of the pavement will also reflect more light, making the area next to the alley cooler.[136] The greening of such alleys or laneways can also involve the planting of native plants to further absorb rain water and moderate temperature. In 2002, a group of Baltimore residents from the Patterson Park neighborhood approached the Patterson Park Community Development Corporation (CDC) looking for a way to improve the dirty, crime-ridden alley that ran behind their homes. Simultaneously, Community Greens also approached the Patterson Park CDC looking for an alley they could use as a pilot project in Baltimore. This led The Luzerne-Glover block being granted a temporary permit from the city to gate their alleyway, despite the fact that it was not yet legal to gate a right-of-way. Eventually the law was changed so that Baltimore residents could legally gate and green the alleys behind their homes.

New life has also come to other alleys within downtown commercial districts of various cities throughout the world with the opening of businesses, such as coffee houses, shops, restaurants and bars.

Another way that alleys and laneways are being revitalized is through laneway housing. A laneway house is a form of housing that has been proposed on the west coast of Canada, especially in the Metro Vancouver area. These homes are typically built into pre-existing lots, usually in the backyard and opening onto the back lane. This form of housing already exists in Vancouver, and revised regulations now encourage new developments as part of a plan to increase urban density in pre-existing neighbourhoods while retaining a single-family feel to the area.[137] Vancouver's average laneway house is one and a half stories, with one or two bedrooms. Typical regulations require that the laneway home is built on the back half of a traditional lot in the space normally reserved for a garage.[138][139]

Toronto also has a tradition of laneway housing and changed regulations to encourage new development.[140] However this was discontinued in 2006 after staff reviewed the impact on services and safety.[141]

Other terms

[edit]English

[edit]- In Australia and Canada the terms lane, laneway, right-of-way[142] and serviceway are also used.

- In some parts of the United States, alleys are sometimes known as rear lanes or back lanes because they are at the back of buildings.

- In parts of Canada, Australia and the United States, mews, a term which originated in London, England, is also used for some alleys or small streets (see, for example, Washington Mews in Greenwich Village, New York City).

Non-English

[edit]- In India the equivalent term is Gali which were prevalent during Moghul Period (1526 C.E. to 1700 C.E.)

- The French allée meaning avenue is used in parts of Europe such as Croatia and Serbia as a name for a boulevard (such as Bologna Alley in Zagreb). The Swedish word "allé" and the German word "Allee", are also based on this French allée (such as Karl-Marx-Allee in Berlin).

- In France, the term allée is not used as the actual word is ruelle, which is described as, "an alley between buildings, often accessible only to pedestrians. These streets are found especially in old city neighbourhoods, particularly in Europe and in the Arab-Muslim world".[143][144] Passage and sentier (path) are also used.

- Czech and some other Slavic languages use the term "ulička" (little street) for alley,[145] a diminutive form of "ulice", the word for street.

- In Montréal, Canada ruelle (diminutive of French rue, a street) is used for a back lane or service alley. There has been an endeavour to green these and some are quite attractive.[146]

- In the Philippines, a common term is eskinita, and refers to any small passage not considered a street between two buildings, especially in shantytowns. The term is ultimately derived from the diminutive of the Spanish word esquina, meaning "corner".

Gallery

[edit]-

Hagay Street, Old City (Jerusalem)

-

Peg Washington's Lane, Graiguenamanagh, County Kilkenny, Ireland

-

View down Jacob's Ladder, Saint Helena

-

A narrow alley of the Vyborg Castle in Vyborg, Russia

-

Rue du Baron in Florac, France

-

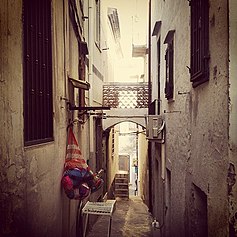

Arco di Via Tirolo, Rodi Garganico, Apulia, Italy

-

Breakneck Steps, Quebec City, around 1870

See also

[edit]- Avenue (landscape) – Straight path or road with a line of trees or large shrubs on both sides, also known as tree alley or allée

- Community Greens – Shared urban green spaces

- Great Yarmouth Row Houses, England

- Bubblegum Alley, San Luis Obispo, California, USA

- Mews – Type of housing above stables

- Right of way (disambiguation)

- Right of way (transit) – Legal authority to use a specific route

- Stairs – Construction that bridges a large vertical distance with steps

- Street – Public thoroughfare in a built environment

- Alley house – style of terraced house fronted on an alleyway

- Laneway house – Form of housing in Canada

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Definition of ALLEY". www.merriam-webster.com. 12 July 2023.

- ^ The Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary

- ^ "Seattle Stairway Walks". Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Stairways of San Francisco". www.sisterbetty.org. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "I'll take the stairs". abhk.org.

- ^ Mette (29 June 2011). "5 Interesting Steps to Rome". Italian Notes. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Sassatelli, R., Consumer Culture: History, Theory and Politics, Sage, 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Lemoine, B., Les Passages Couverts, Paris: Délégation à l'action artistique de la ville de Paris [AAVP], 1990. ISBN 9782905118219.

- ^ Gibert-Flutre, Marie; Imai, Heide (2020). Asian Alleyways An Urban Vernacular in Times of Globalization. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789463729604.

- ^ Michael Meyer. "The Death and Life of Old Beijing".

- ^ Kane, David (2006). The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage. Tuttle Publishing. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8048-3853-5. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "Architectural Record | McGraw-Hill Construction". Archrecord.construction.com. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Booth, Robert; Watts, Jonathan (5 June 2008). "Charles takes on China to save Ming dynasty". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Beijing Hutong: "Qianshi Hutong | Beijing Hutong". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014..

- ^ Frommer's Shanghai Day By Day – Page 162 Graham Bond – 2011 1912 "1917 China's first shopping mall, the Sincere Department Store, Lilong, or Longtang Li means "neighborhood", and long means "alley"."

- ^ Walking between slums and skyscrapers: illusions of open space in ... - Page 160 Tsung-yi Michelle Huang – 2004 "Shanghainese call lilong, their characteristic residential design, as longtang. "Long" means alley or lane and "tang" parlor or hall. "All houses are facing the lanes and lanes become the public space used by all residents. Enclosed, the whole ...

- ^ Postsocialism and Cultural Politics: China in the Last Decade of ... - Page 196 Xudong Zhang – 2008 "As long means a lane and tang the front room of a house, longtang either refers to a lane that connects houses or a group of houses connected by lanes. Longtang however might not be so explicit as lilong for the li in lilong means ..."

- ^ Narrating Architecture: A Retrospective Anthology Page 474 James Madge, Andrew Peckham – 2006 "Four sketches by Feng Zikai of Shanghai's alley life: clockwise from top left: lowering a basket down to the alley to purchase ... these activities were certainly not considered in the original design of the lilong, but were gradually introduced in the practice of everyday life within the community. A local writer, Shen Shanzeng, has named this special way of living as 'life in the alley' (long-tang ren-sheng)."

- ^ Cities Surround The Countryside: Urban Aesthetics in Postsocialist ... - Page 320 Robin Visser – 2010 "Chunlan Zhao refers to the generalization that Shanghai without its longtang is no longer Shanghai, in From ... archway; li means neighborhood; long ... means alley. ... The earliest lilong compound resembled the lifang residential ward in imperial capitals, but instead of being enclosed by ...

- ^ a b c "Golden Gai – An Unmissable Tokyo Experience". www.unmissabletokyo.com.

- ^ "Hiragan Times, "Shinjuku – a Town for Everybody that Has Just About Everything"". Archived from the original on 13 January 2014.

- ^ Imai, Heide (2017). Tokyo Roji: The Diversity and Versatility of Alleys in a City in Transition. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-94910-2.

- ^ Asian alleyways : an urban vernacular in times of globalization. Marie Gilbert-Flutre, Heide Imai, International Institute for Asian Studies. Amsterdam. 2020. ISBN 978-94-6372-960-4. OCLC 1160036625.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Kim, Annette Miae (2015). Sidewalk city : remapping public space in Ho Chi Minh City. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-11936-6. OCLC 906576927.

- ^ "Sydney Tours". www.sydney.com. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Laneways of The Rocks". www.visitsydneyaustralia.com.au. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Wood, Simon. "Sydney laneway revival". ARCHITECTUREAU. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ "Chinatown and Haymarket". Sydney.com. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Little Latrobe Street and the Historical Significance of Melbourne's Laneways". Public Record Office of Victoria. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Melbourne Laneways". melbourneheritage.org.au. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Bate, Weston (1994). Essential But Unplanned: The Story of Melbourne's Lanes. State Library of Victoria in conjunction with the City of Melbourne. ISBN 978-0-7306-3598-7.

- ^ "Perth Public Spaces Public Life" (PDF). Gehl Architects. 2009. p. 36. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Romano, Mary-Anne (12 March 2012). "Perth CBD evolving to be more pedestrian friendly". Science Network WA. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Bars breathe new life into Perth Lanes". The West Australian. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "City of Perth Council Minutes" (PDF). 26 August 2008. pp. 45–49. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Impasses de Bruxelles, Lucia Gaiardo, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale-Ville de Bruxelles, 2000

- ^ a b "Tourismus-Reutlingen: An eye of a needle with world fame". Wirtschaft-Necker Alb. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ^ Glenday, Craig, ed. (2009). Guinness World Records 2009. Random House Publishing Group. p. 493. ISBN 978-0-553-59256-6.

- ^ "Regio-Report Neckar-Alb Aus der Region" (in German). E-Paper – Wirtschaft-Neckar Alb. April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Signon, Helmut (2006), Alle Straßen führen durch Köln, Greven Verlag, ISBN 3-7743-0379-7 and Priebe, Ilona (2004), Kölner Straßennamen erzählen. Zwischen Schaafenstraße und Filzgraben, Bachem J.P. Verlag, ISBN 3-7616-1815-8

- ^ unknown, France Today (4 December 2012). "Lyon's Traboules – French History".

- ^ "vicolo – Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. 8 November 2021.

- ^ (calli) of Venice[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Stegen in Amsterdam". Studiokoning.nl. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ a b Stahre, Nils-Gustaf; Fogelström, Per Anders & Ferenius, Jonas & Lundqvist, Gunnar (2005) [1986]. Stockholms gatunamn (utgåva 3:e upplagan). Stockholm: Stockholmia förlag. Libris 10013848. ISBN 91-7031-152-8.

- ^ a b "Innerstaden: Gamla stan". Stockholms gatunamn (2nd ed.). Stockholm: Kommittén för Stockholmsforskning. 1992. p. 62. ISBN 978-91-7031-042-3.

- ^ "City Street Names". www.maps.thehunthouse.com. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Londonist's Back Passage". Londonist.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b John Biddulph Martin (1892). "The Grasshopper" in Lombard Street. University of Michigan. Scribner & Welford.

- ^ J. Pelzer and L. Pelzer, "Coffee Houses of Augustan London," History Today, (October, 1982), pp. 40–47.

- ^ Larry Neal. "How It All Began: The Monetary and Financial Architecture of Europe during the First Global Capital Markets: 1648–1815." Archived 14 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "London Stock Exchange | London Stock Exchange". www.londonstockexchange.com. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Brydges Place, Covent Garden, London, the narrowest alleyway in London". www.urban75.org.

- ^ "The Lamb and Flag". Pubs.com. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ^ F. H. W. Sheppard (1970). Survey of London: volume 36: Covent Garden. Institute of Historical Research. pp. 182–184. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ^ John Richardson (2000). The Annals of London. University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-520-22795-8. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 427–428, see page 428. para 2, six lines from the end.

....and by his orders a band of roughs set on the poet in Rose Alley, Covent Garden, and beat him....

- ^ "January 2007 – Cecil Court". Film London. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ "Filming in Cecil Court | thelastbookshop". Thelastbookshop.wordpress.com. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ "The London Project -Home". londonfilm.bbk.ac.uk.

- ^ Cairns, David (2006), Mozart and his Operas, University of California Press, p. 17, ISBN 978-0-520-22898-6

- ^ Sadie, Stanley (2005), Mozart, the Early Years 1756–1781, W. W. Norton & Company, pp. 64–5, ISBN 978-0-393-06112-3

- ^ "Islington: Growth | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Interesting information about Lewes, East Sussex". Area Information by Quicksold. 25 June 2023.

- ^ StreetCheck. "Interesting Information for Paines Twitten, Lewes, BN7 1UB Postcode". StreetCheck.

- ^ "Lingfield villagers seek plastic bag-free zone". BBC. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ Loughton & District Historical Society Newsletter 136, April 1997 Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "A History of Brighton". Localhistories.org. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ "Barbican Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2014. Plymouth City Council

- ^ Mary Palmer, A dialogue in the Devonshire dialect, by a lady [M. Palmer]: to which is added a glossary, by J.F. Palmer, 1837.

- ^ The Disappearing Dictionary: A Treasury of Lost English Dialect Words. Pan Macmillan,2015.

- ^ Franks, Richard (20 September 2018). "A Comprehensive Guide to Brummie Slang". theculturetrip.com. Culture Trip. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Entry – the alley between terraced houses....Gully – an alleyway, or space round the back of houses.

- ^ "Walking the Jitties" Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the Barrow Upon Soar Heritage Group website

- ^ Wilson, David (1974). Staffordshire Dialect Words: A Historical Survey. Moorland Publishing Company.

- ^ "Geograph:: Shrewsbury's shuts and passages". www.geograph.org.uk.

- ^ Arfin, Ferne. "United Kingdom Travel: Finding Medieval York:Walking the Snickelways and Ginnels of Medieval York" Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine About.com

- ^ "Whitby Walks | Whitby ghost walks with Dr Crank".

- ^ The Wynd (1 January 1970). "wynd richmond – Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Published by City of Newcastle upon Tyne Education and Libraries Directorate, 2002

- ^ BBC. "Putting SY on the Wordmap". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Ginnel". Yorkshire Historical Dictionary. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Harris, S (1996). The Place Names of Edinburgh. London: Steve Savage. p. 28. ISBN 1-904246-06-0.

- ^ Town and Regional Planning Programme, University of Dundee. "Conservation Glossary, entry for "pend"". Archived from the original on 12 February 1997. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Photographs and newspaper cuttings". www.bpra.org.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Medina definition". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "7 car-free cities". Mother Nature Network.

- ^ "In the lanes of old St. John's – SkyscraperPage Forum". skyscraperpage.com. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Quebec, Canada". www.ndsu.edu. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Québec City and Area – Stairways". Québec City Tourism. 2011. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ "Fan Tan Alley" Archived 7 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the Victoria's China Town website

- ^ Ringuette, Janis (2007). "Waddington Alley: A 1908 Street Experience". Hidden in Plain Sight. Islandnet. Archived from the original on 28 April 2011.

- ^ Huston, John W. (1977). "Annapolis: an eighteenth-century analysis". Conspectus of History. 1 (4): 49.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. "Celebrating Annapolis's Storied Shortcuts". The Washington Post (27 January 2005) p.AA14.

- ^ Backbay alleys

- ^ "A Stroll Down Dueler's Alley" Archived 7 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the Charleston Gateway website

- ^ Poston, Jonathan H. The Buildings of Charleston: A Guide to the City's Architecture. Columbia, SC, University of South Carolina Press, 1997, pp.136–7.

- ^ "SCDAH". www.nationalregister.sc.gov. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Alleys and the Making of Chicago's Shadow City". WBEZ Chicago. 10 October 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Alleys". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Chicago's Green Alley Program". Center for Environmental Excellence | AASHTO. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "City of seven hills". The Cincinnati Enquirer. 4 December 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ "Walking the Steps of Cincinnati — 1998". Ohio University Press & Swallow Press. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Devin Parrish (January 1998). "Observer: Climb Every Hill". Cincinnati Magazine. p. 22.

- ^ "CityLab – Bloomberg". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Most Historic Alley in Delaware". RoadsideAmerica.com.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (23 October 2005). "Are Manhattan's Right Angles Wrong?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Rosenberg, Joe (8 January 2019). "Cortlandt Alley". 99% Invisible. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ AIA Guide, p.131-133

- ^ "Alleys". Forgotten New York. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ AIA Guide, p.145

- ^ AIA Guide, p.594

- ^ AIA Guide, p.627

- ^ AIA Guide, p.298

- ^ "History" Archived 7 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the Elfreth's Alley Association website

- ^ "Elfreth's Alley Museum". Elfreth's Alley Museum. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Colin. "About Philadelphia: Alleys Much Treasured for Their Tiny Houses" The New York Times (18 December 1984)

- ^ "39°56'46.5"N 75°08'47.5"W". 39°56'46.5"N 75°08'47.5"W.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps.

- ^ "Pyle's Great Column on Pittsburgh". Pittsburgh Press. 19 April 1945.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Steps". www.frontiernet.net.

- ^ "San Francisco: 10 Things to Do — 3. The Stairs of Telegraph Hill – TIME". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ www.belden-place.com, Belden Place Official Website

- ^ Sam Whiting (30 June 2006). "The limited confines of San Francisco's French Quarter don't make it any less foreign". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 1 January 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- ^ Seattle All Stairs: "Seattle Stairs – map of all public stairs with guides to 30 walks". Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014..

- ^ a b "Green Alleys". www.chicago.gov. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "The Chicago Green Alley Handbook" Archived 22 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine on the City of Seattle website

- ^ "Green Alleys". Trust for Public Land. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Green Alley Projects" Archived 4 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the District of Columbia Department of Transportation website

- ^ "About Us" Archived 4 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the Integrated Alleys website

- ^ "archive.ph". archive.ph. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Laneway houses appeal to boomer generation". 8 November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012.

- ^ Vancouver, City of. "Build a new house or laneway house". vancouver.ca. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Livable Lanes: A Study of Infill Laneway Housing in Vancouver and Other B.C. Communities" Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine on the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation website (November 2009)

- ^ "News". Canadian Architect. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Crowther, William G. "Toronto Staff Report" (20 June 2006)

- ^ "Rights-of-Way or Laneways in Established Areas- Guidelines" (PDF). Planning Bulletin No 33. Western Australian Planning Commission. July 1999. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ French Wikipedia article, Google translation (edited).

- ^ Google translation

- ^ "slovnik.seznam.cz Translation of "ulička"". Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ "Montreal's Best Alleyways". 16 July 2010.

Bibliography

- DuSablon, Mary Anna, Walking the Steps of Cincinnati. Athens, OH.: Ohio University Press, 1998.

- Hage, Sara A., Alleys: Negotiating Identity in Traditional, Urban, and New Urban Communities. M.A. Thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2008.

- Long, David, Hidden City: The Secret Alleys, Courts & Yards of London's Square Mile. London: The History Press, 2011.

- Regan, Bob, The Steps of Pittsburgh: Portrait of a City. Pittsburgh, PA.: The Local History Company, 2004.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

External links

[edit] Media related to Alleys at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alleys at Wikimedia Commons