Ogaden War

| Ogaden War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ethiopian Civil War, the Ethiopian–Somali conflict, and the Cold War | |||||||

Cuban artillerymen prepare to fire at Somali forces in the Ogaden | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Beginning of war: 35,000–47,000 soldiers[16] 37 aircraft, 62 tanks, 100 armored vehicles[8] Later: 64,500 soldiers[17] 1,500 Soviet advisors 12,000–18,000 Cuban soldiers[18][19] 2,000 Yemeni soldiers[20] |

Beginning of war: 31,000[21]–39,000 soldiers[22] 53 aircraft, 250 tanks, 350 armored vehicles, and 600 artillery guns[23][24] Later: 45,000–63,000 soldiers[22][17] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Ethiopia: 6,133 killed[25] 8,207 wounded[26] 2,523 captured[26] Equipment losses: 23 aircraft[25] 139 tanks[25] 108 APCs[25] 1,399 vehicles[25] Cuba: 163 killed[26][27] 250 wounded[28] 6 tanks[28] South Yemen: 90 killed 150 wounded[28] Soviet Union: 33 advisors killed[29] |

Somalia: 6,453 killed 2,409 wounded[25] 275 captured[25] Equipment losses: 34 aircraft[30] 154 tanks[30] 270 APCs[30] 624 vehicles[30] 295 artillery guns[30] | ||||||

|

25,000 civilians killed[27] 500,000 Somali inhabitants of Ethiopia displaced[31][32] | |||||||

The Ogaden War, also known as the Ethio-Somali War (Somali: Dagaalkii Xoraynta Soomaali Galbeed, Amharic: የኢትዮጵያ ሶማሊያ ጦርነት, romanized: ye’ītiyop’iya somalīya t’orinet), was a military conflict fought between Somalia and Ethiopia from July 1977 to March 1978 over the sovereignty of Ogaden. Somalia's invasion of the region, precursor to the wider war,[33] met with the Soviet Union's disapproval, leading the superpower to end its support for Somalia and to fully support Ethiopia instead.

Ethiopia was saved from defeat and permanent loss of territory through a massive airlift of military supplies worth $1 billion, the arrival of more than 12,000 Cuban soldiers and airmen[34] and 1,500 Soviet advisors, led by General Vasily Petrov. On 23 January 1978, Cuban armored brigades inflicted the worst losses the Somali forces had ever taken in a single action since the start of the war.[35]

The Ethiopian-Cuban force (equipped with 300 tanks, 156 artillery pieces and 46 combat aircraft)[27] prevailed at Harar and Jijiga, and began to push the Somalis systematically out of the Ogaden. On 23 March 1978, the Ethiopian government declared that the last border post had been regained, thus ending the war.[36] Almost a third of the regular SNA soldiers, three-eighths of the armored units and half of the Somali Air Force had been lost during the war. The war left Somalia with a disorganized and demoralized army as well as a heavy disapproval from its population. These conditions led to a revolt in the army which eventually spiraled into the ongoing Somali Civil War.[37]

Background

The Ogaden is a vast plateau that is overwhelmingly inhabited by Somali people. It represents the westernmost region inhabited by the Somalis in the Horn of Africa, and is located to the south and southeast of the Ethiopian Highlands.[38] During the pre-colonial era the Ogaden region was neither under Ethiopian rule, nor terra nullius, as it was occupied by organized Somali communities.[39] Independent historical accounts are unanimous that previous to the penetration into the region in the late 1880s, Somali clans were free from the control of Ethiopian Empire.[40]

Menelik ll's invasions and Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897

During the late 1880s, as European colonial powers advanced into the Horn of Africa, Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II launched invasions into Somali-inhabited territories as part of his efforts to expand the Ethiopian Empire. These encroachments primarily affected the Ogaden region. The Ethiopian Empire imported a significant amount of firearms from European powers in this period,[41][42] and the large scale importation of European arms completely upset the balance of power between the Somalis and the Ethiopian Empire, as the colonial powers blocked Somalis from accessing firearms.[43] Control over the Ogaden was expressed through intermittent raids and expeditions that aimed to seize Somali livestock as tribute.[44] In exchange for commercial privileges for British merchants in Ethiopia and the neutrality of Menelik II in the Mahdist War, the British signed the Anglo-Ethiopian treaty of 1897. The agreement cededed large parts of Somali territory to Ethiopia, despite being a legal breach of the legal obligation made by the protectorate.[45]

As indiscriminate raiding and attacks by imperial forces against the Somalis grew between 1890 and 1899, those residing in the plains around the settlement of Jigjiga were in particular targeted. The escalating frequency and violence of the raids resulted in Somalis consolidating behind the anti-colonial Dervish Movement under the lead of Sayyid Mohamed Abdullah Hassan.[46] The Ethiopian hold on Ogaden at the start of the 20th century was tenuous, and administration in the region was "sketchy in the extreme". Sporadic tax raids into the region often failed and Ethiopian administrators and military personnel only resided in the towns of Harar and Jigjiga.[47] Attempts at taxation in the region were called off following the massacre of 150 Ethiopian troops in January 1915.[48]

Second Italo-Ethiopian War and World War II

During the 1920s and 1930s, there were no permanent Ethiopian settlements or administration in the Ogaden or any Somali inhabited land, only military encampments.[49] In the years leading up to the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935, the Ethiopian hold on the Ogaden remained tenuous.[50] Due to native hostility, the region had nearly no Ethiopian presence until the Anglo-Ethiopian boundary commission in 1934 and the Wal Wal incident in 1935.[48] Only during 1934, as the Anglo-Ethiopian boundary commission attempted to demarcate the border, did Somalis who had been transferred to the Ethiopian Empire by the British during the 1897 Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty realize that they had been placed under Abyssinian rule. In decades following the treaty, Somalis remained unaware about the transfer of their region due to the lack of 'any semblance' of effective administration of control being present over the Somalis to indicate that they were being annexed by the Ethiopian Empire.[45]

Following the end Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1937, and the outbreak of World War II, the Ogaden was united under a single administration with the British and Italian Somaliland's. After the defeat of Italy, power transferred to the British military administration.[51] The British Foreign Secretary proposed to keep the Somalis territories unified after the war, but was rejected by the Ethiopians and France (then controlling French Somaliland) who wanted a return to the pre-war status quo.[51] On 31 January 1942, Ethiopia and the United Kingdom signed the second "Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement", ending British military occupation in most of Ethiopia except Ogaden.[52]

The last remaining British controlled parts of the region were transferred to Ethiopia in 1955. The population of the Ogaden did not perceive themselves to be Ethiopians and were deeply tied to Somalis in neighboring states. Somalis widely considered Ethiopian rule in the Ogaden to be a case of African colonial subjugation.[53] After Italy lost control of Italian Somaliland during the Second World War, these regions came under British military administration. It was during this period that Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie expressed a keen interest in the territory, which his government deemed as a lost province of the empire. He laid claim to them openly, asserting that the ancient Somali coastal region of Banaadir (which encompasses Mogadishu) as well as the adjacent Indian Ocean coastline, rightfully belonged to Ethiopia based on 'historical grounds'.[54]

Ogaden and Haud handovers

Following World War II, Somali leaders in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia repeatedly put forward demands for self-determination, only to be ignored by both Ethiopia and the United Nations.[55] After the establishment of the United Nations, Ethiopia submitted a memorandum to the UN, contending that prior to the era of European colonialism, the Ethiopian empire had encompassed the Indian Ocean coastline of Italian Somaliland.[54] Somali nationalists unsuccessfully fought at the UN to prevent the establishment of Ethiopian administration in the Ogaden after WWII.[51]

In 1948, the British Military Administration, which had been in control of the Ogaden since the defeat of Italy during WWII, commenced a withdrawal. This transition saw the replacement of British officials with Ethiopian counterparts between May and July of that year in a significant handover process.[56] After the handover, Ethiopian administration resumed in Jigjiga for the first time in 13 years. Then, on 23 September 1948, following the withdrawal of British forces and the appointment of Ethiopian district commissioners, vast areas of the Ogaden east of Jijiga were placed under Ethiopian governance for the first time in their history.[56] Under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,[57] the British gave the Haud and the Ogaden to Ethiopia, based on the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897.[45] Britain included the provision that the Somali residents would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over the area.[58] In attempt to fulfill the obligations of its original protection treaties it had signed with the Somalis, the British unsuccessfully bid in 1956 to buy back the lands it had unlawfully turned over.[59]

n the mid-1950s, Ethiopia for the first time controlled the Ogaden and began incorporating it into the empire. In the 25 years following the commencement of Ethiopian rule in this era, hardly a single paved road, electrical line, school or hospital was built. The Ethiopian presence in the region was always colonial in nature, primarily consisting of soldiers and tax collectors. The Somalis were never treated as equals by the Amhara who had invaded the region during Menelik's expansions and were scarcely integrated into the Ethiopian Empire.[60] During the late 1940s and 1950's, covert Somali organizations in the Ogaden formed with the aim of freeing the region from Ethiopian rule.[61][62]

1963 Ogaden uprising and First Ethiopian-Somali War

During the 1960's, the newly independent Somali Republic and the Ethiopian Empire under Haile Selasie came on the verge of full scale war over the Ogaden issue, particularly during 1961 and 1964. In the years following there had been a number of reported and unreported skirmishes between Ethiopian and Somali troops.[51] In 1963, the first major post-war rebellion in the region broke out. Known as 'Nasrallah' or the Ogaden Liberation Front, the organization fought a guerrilla war for self-determination. It began with 300 men and soon swelled to 3,000.[63][64] The Ethiopian Imperial Army launched a large scale counterinsurgency campaign during the summer and fall of 1963. The imperial governments reprisals during the counterinsurgency campaign, which consisted large scale artillery bombardments of Somali cities in the Ogaden, resulted in rapidly deteriorating relations between the Ethiopian Empire and the Somali Republic, eventually resulting in the first interstate war between Ethiopia and Somalia in 1964 .[64][61]

In a bid to control the population of the region during the 1963 revolt, an Ethiopian Imperial Army division based out of the city of Harar torched Somali villages and carried out mass killings of livestock. Watering holes were machine gunned by aircraft in order to control the nomadic Somalis by denying them access to water. Thousands of residents were driven out from the Ogaden into Somalia as refugees.[65] In the years following, insurgent activity continued but declined over the late 1960's due to pressures from both the Ethiopian and Somali governments. The Nasrallah insurgents formed the foundation of the future Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF).[66][67] Somali insurgents remained active in the Ogaden hinterlands until the first WSLF operations began operations in 1974.[68]

October Coup and Somali Democratic Republic

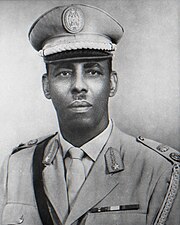

In October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somali President Shermarke was shot dead by one of his bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on 21 October (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[69]

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Ali Korshel. Kediye officially held the title of "Father of the Revolution", and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[70] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[71][72] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[73] In addition to Soviet funding and arms support provided to Somalia, Egypt sent to the country millions of dollars' worth of arms shipments.[8] Though the United States had offered Somalia arms support prior to the 1977 invasion, the offer was withdrawn following the news of Somali troops operating in the Ogaden Region.[74]

Western Somali Liberation Front insurgency

In the early 1970s, the rebel organization fighting for Ogaden's self-determination, Nasrallah, began to disintegrate. In response, veteran insurgents and young intelligentsia, displaced from the Ogaden in the 1960s and now part of Siad Barre's government, lobbied for renewed armed struggle.[75] After Haile Selassie’s regime was toppled by the Derg, conditions in the Ogaden worsened. A severe drought hit the region, causing mass suffering, while the Derg suppressed news and increased military oppression. By 1974-1975, intense pressure from Ogaden Somalis on Siad Barre's government rapidly grew.[76]

By 1975, the Somali government had been convinced to aid the movement.[75] According to professor Haggai Erlich, the war in Ogaden also had a religious dynamic as the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) had established links with the Muslim World League in 1976, later the Somali Abo Liberation Front (SALF) founded by Waqo Gutu involved Oromo Muslim militias cooperating with the WSLF. Another squadron named after sixteenth century Islamic leader Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi formed the Harari, a reminiscent of the medieval Ethiopian–Adal War.[77]

Guerrilla warfare began in both the northern and southern regions in early 1976 and spread to southeastern Bale and Sidamo by year’s end. The terrain, a mix of arid scrubland, mountains, and woods, was familiar to the fighters, with friendly local inhabitants. Infiltrating from the Somali Republic, the guerrillas moved swiftly, dismantling state presence by destroying government offices and targeting police and civilian administration. The WSLF movement had four brigades, known in Somali as 'Afar Gaas.'.[78] At the start of 1977, the WSLF began escalating it attacks against Ethiopian troops.[79] During early 1977, with the exception of towns strategically positioned on vital routes and intersections, the WSLF effectively controlled most of the Ogaden lowlands. The rebels employed hit-and-run tactics, targeting the Ethiopian army at its vulnerable points and then blending into a predominantly supportive local population. These tactics eroded the morale of the Ethiopian troops, compelling them to retreat to strongholds. The Ethiopian army found itself confined to garrison towns, many of which were besieged. While any WSLF attempt to storm these garrison towns invited devastating firepower from the Ethiopian defenders, travel between towns became perilous for the Ethiopian troops. Military and civilian vehicles required armed escorts, often falling into ambushes or encountering land mines.[80]

Somali strategy

Under the leadership of General Mohammad Ali Samatar, Irro and other senior Somali military officials were tasked in 1977 with formulating a national strategy in preparation for the war against Ethiopia to assist the Western Somali Liberation Front.[81] President Barre believed a Somali military intervention would allow the WSLF to press home their advantage and achieve total victory.[82] This was part of a broader effort to unite all of the Somali-inhabited territories in the Horn region into a Greater Somalia (Soomaaliweyn).[83]

A distinguished graduate of the Soviet Frunze Military Academy, Samatar oversaw Somalia's military strategy. During the Ogaden War, Samatar was the Commander-in-Chief of the Somali Armed Forces.[81] He and his frontline deputies faced off against their mentor and former Frunze alumnus, General Vasily Petrov, assigned by the USSR to advise the Ethiopian Army. A further 15,000 Cuban troops, led by General Arnaldo Ochoa, also supported Ethiopia.[84][85] General Samatar was assisted in the offensive by several field commanders, most of whom were also Frunze graduates:[86]

- General Yussuf Salhan commanded the SNA on the Jijiga Front, assisted by Colonel A. Naji, capturing the area on August 30, 1977. (Salhan later became Minister of Tourism but was expelled from the Somali Socialist Party in 1985.)

- Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed commanded the SNA on the Negellie Front. (Ahmed later led the rebel SSDF group based in Ethiopia.)

- Colonel Abdullahi Ahmed Irro commanded the SNA on the Godey Front.

- Colonel Ali Hussein commanded the SNA in two fronts, Qabri Dahare and Harar. (Hussein eventually joined the Somali National Movement in late 1988.)

- Colonel Farah Handulle commanded the SNA on the Warder Front. (He became a civilian administrator and Governor of Sanaag, and in 1987 was killed in Hargheisa one day before he took over governorship of the region.)

- General Mohamed Nur Galaal, assisted by Colonel Mohamud Sh. Abdullahi Geelqaad, commanded Dirir-Dewa, which the SNA retreated from. (Galaal later became Minister of Public Works and leading member of the ruling Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party.)

- Colonel Abdulrahman Aare and Colonel Ali Ismail co-commanded the Degeh-Bur Front. (Both officers were later chosen to reinforce the Harar campaign; Aare eventually became a military attaché and retired as a private citizen after the SNA's collapse in 1990.)

- Colonel Abukar Liban 'Aftooje' initially served as acting logistics coordinator for the Southern Command and later commanded the SNA on the Iimeey Front. (Aftoje became a general and military attaché to France.)

Somali Air Force

The Somali Air Force was primarily organized along Soviet lines, as its officer corps were trained in the USSR.[28][87]

Somali Air Force operational aircraft

Derg

In September 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie had been overthrown by the Derg military council, marking a period of turmoil. The Derg quickly fell into internal conflict to determine who would have primacy.[89] Meanwhile, various anti-Derg groups as well as separatist movements began emerging throughout the country.

One of the separatist groups seeking to take advantage of the chaos was the pro-Somalia Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) operating in the Somali-inhabited Ogaden; by late 1975, the group had attacked numerous government outposts. WSLF controlled most of the Ogaden, the first time since World War II that all of Somalia had been united (with the exception of the Northern Frontier District in Kenya). The victory in Ogaden occurred primarily because of support from the Harari populace who had aligned with the WSLF.[90][91] From 1976 to 1977, Somalia supplied arms and other aid to the WSLF.

Opposition to the reign of the Derg was the main cause of the Ethiopian Civil War. This conflict began as extralegal violence between 1975 and 1977, known as the Red Terror, when the Derg struggled for authority, first with various opposition groups within the country, then with a variety of groups jockeying for the role of vanguard party. Though human rights violations were committed by all sides, the great majority of abuses against civilians as well as actions leading to devastating famine were committed by the government.[92]

A sign that order had been restored among Derg factions was the announcement on February 11, 1977, that Mengistu Haile Mariam had become head of state. However, the country remained in chaos as the military attempted to suppress its civilian opponents in a period known as the Red Terror (Qey Shibir in Amharic). Despite the violence, the Soviet Union, which had been closely observing developments, came to believe that Ethiopia was developing into a genuine Marxist–Leninist state and that it was in Soviet interests to aid the new regime. They therefore secretly approached Mengistu with offers of aid, which he accepted. Ethiopia closed the U.S. military mission and its communications center in April 1977.[93][94][95]

In June 1977, Mengistu accused Somalia of infiltrating SNA soldiers into the Somali area to fight alongside the WSLF. Despite considerable evidence to the contrary, Barre strongly denied this, saying SNA "volunteers" were being allowed to help the WSLF.

Ethiopian Air Force

The Ethiopian Air Force (ETAP) was formed thanks to British and Swedish aid during the 1940s and 1950s, and started receiving significant US support in the 1960s. Despite its small size, the ETAP was an elite force, consisting of hand-picked officers and running an intensive training program for airmen at home and abroad.[96]

The Ethiopian Air Force benefited from a US Air Force aid program. A team of US Air Force officers and NCOs assessed the force and provided recommendations as part of the Military Advisory and Assistance Group. The ETAP was restructured as a US-style organization. Emphasis was given to training institutions. Ethiopian personnel were sent to the US for training, including 25 Ethiopian pilots for jet training, and many more were trained locally by US Defense personnel.[97]

Prior to 1974, the Ethiopian Air Force mainly consisted of a dozen F-86 Sabres and a dozen F-5A Freedom Fighters. In 1974, Ethiopia requested the delivery of McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom fighters, but the US instead offered it 16 Northrop F-5E Tiger IIs, armed with AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, and two Westinghouse AN/TPS-43D mobile radars (one of which was later positioned in Jijiga).[98] Due to human rights violations in the country, only 8 F-5E Tiger IIs had been delivered by 1976.[96]

Ethiopian Air Force operational aircraft

-

F-86 Sabre, 14 units[98]

-

Canberra B.Mk.2 bombers, 2 units[87]

-

T-28 Trojan, 8 units[87]

-

Aérospatiale SA.316 Alouette, 3 units[87]

Castro's trip to Aden

In early 1977, Fidel Castro brought together the leaders of Somalia, Ethiopia and Democratic Yemen during a March meeting in Aden, Democratic Yemen, where he suggested an Ethiopian-Somali-Yemeni Socialist Federation.[99] The Somali delegation were open to a 'loose-knit' federation[100] on the basis that self-determination be extended to the Ogaden and that the Somali people be united.[100] They had come to the conference believing that long awaited negotiations for a solution to the Ogaden problem had finally begun.[101]

During the meeting, President Barre spoke extensively about the Ogaden's occupation and Somalia's struggle for self-determination. Ethiopian President Mengistu spoke briefly, stating he had nothing to suggest since the Ogaden was an 'integral part' of Ethiopia. Mengistu warned Barre to accept the status quo, but Barre stated the issue couldn't be side stepped. A Cuban delegate intervened, suggesting from a 'socialist perspective' that Somalia should accept the status quo, likening the Ogaden issue to Mexico reclaiming Texas. Barre rejected this, stating he sought self-determination for Somalis under Ethiopian occupation, not annexation, and argued that a true socialist view should support self-determination.[101] Mediators proposed making the Ogaden an autonomous zone, which the Ethiopians found excessive and the Somalis saw as insufficient.[99] As talks broke down, Barre requested a private meeting with Mengistu but was rejected, and the discussions soon collapsed. The Somalis left the Aden meeting believing it was organized to pressure them on the Ogaden issue.[101] The conference effectively called for Somalia to drop its support for self-determination, which Barre couldn’t accept, as he couldn't speak for the WSLF.[102] As early as May 1977, Cuban military personnel began arriving in Ethiopia.[103]

Somalia and Ethiopia each blamed the other for the failure of the Aden meeting, but Castro backed Mengistu, who emphasized his pro-Soviet credentials, while Barre focused on Somali self-determination and ending Ethiopian rule in Ogaden. Another round of talks, arranged by Moscow in July 1977 to prevent war, never occurred, as the Russians saw no room for compromise between the entrenched positions. These July talks were the last chance for a socialist framework settlement, but they too collapsed..[99]

History

Course of the war

For some time, the Western Somali Liberation Front, had been conducting guerilla operations in the Ogaden. By June 1977, it had succeeded in forcing the Ethiopian army out of much of the region and into fortified urban centers.[82]

Somali invasion (July–August 1977)

The Somali National Army (SNA) committed to invade the Ogaden on July 12, 1977, according to Ethiopian Ministry of National Defense documents (other sources state July 13 or 23).[104][105]

According to Gebru Tareke, the invaders had 23 mechanized battalions, 9 armored battalions, 4 airborne battalions and 9 artillery battalions which numbered around 31,000 to 39,000 men, 53 fighter jets, 250 tanks, 350 armored personnel carriers (APCs), and 600 artillery pieces. Arrayed against such a force were Ethiopia's 3 infantry brigades, a mechanized brigade, 2 tank and 2 artillery battalions, and 2 air defense batteries with a total of 35,000 to 47,000 regular troops and militiamen. Despite the clear disadvantage in fighting men, the Somalis held numerical superiority over the Ethiopians in terms of tanks, artillery, and armored personnel carriers (APCs). The Ethiopian army was thinly spread, as the army and militia units were scattered all over the vast plains of the Ogaden, its best units were engaged in the Eritrean War of Independence to the north. The 10th Mechanized Brigade was stationed at Jijiga, the 5th, 9th, and 11th Infantry Brigades were based at Gode, Kebri Dahar, and Degehabur. In addition, an infantry battalion was stationed at each frontier outpost, such as Aware, Warder, Galadin, and Mustahil. All these army units were placed under the 3rd Division, headquartered in Harar.[104]

With only infantry and anti-tank guns, Ethiopian troops found themselves in a precarious situation. Somali tanks swiftly advanced westward, penetrating 700 kilometers into Ethiopia and capturing 350,000 square kilometers. Their advantage stemmed from superior equipment and organization, particularly in tanks. They employed an offensive strategy centered on speed and quickly exploiting weaknesses. Their attack pattern involved massive infiltrations behind the front lines, intense artillery barrages, and coordinated mechanized bombing raids. A militia brigade from the 219th Battalion were deployed to Gode to support the 5th Infantry Brigade, which had endured relentless artillery bombardment since July 13. Despite their efforts, Gode was captured by the Somalis on July 25. Without artillery or air support to cover their retreat, the Ethiopian defenders were effectively annihilated, with only 489 out of the 2,350 militiamen managing to return to Harar, the rest presumed dead.[17]

The 9th brigade at Kebri Dahar fought fiercely before retreating to Harar on July 31. The 11th Infantry Brigade stationed at Degehabur persisted in combat until the end of July when it received orders to withdraw to Jijiga. Soviet General Vasily Petrov had to report back to Moscow the "sorry state" of the Ethiopian Army. The 3rd and 4th Ethiopian Infantry Divisions that suffered the brunt of the Somali invasion had practically ceased to exist. Within less than a month of the invasion, 70% of the Ogaden had been taken by the SNA-WSLF force. Somalia easily overpowered Ethiopian military hardware and technology. The Soviet-made T-54 and T-55 main battle tanks had, in Gebru's words, "bigger guns, better armour, greater range and more maneuverability than Ethiopia's aging M-41 and M-47 [American-made tanks]." Similarly, Ethiopia's American-made 155mm artillery pieces were outmaneuvered and outranged by Somalia’s Soviet- made 122mm D-30 field howitzer guns. Over the years, the Soviets had been arming Somalia’s military forces with the latest weapons. Somali commanders calculated that their stockpiles of Soviet arsenal would enable them to wage war for six months. They anticipated that once the Soviets learned of the invasion, they might terminate the flow of arms to Somalia. The Somali objective was thus to occupy the whole of the Ogaden and by December 1977, before the suspension of Soviet weapons shipments could have a serious impact on their offensive.[105][82]

The Somali forces did suffer some early setbacks; as on July 16, just four days after the beginning of the invasion, the Somalis launched a surprise attack on Dire Dawa with an infantry brigade, two artillery battalions, a tank battalion, a ballistic missile rocket battery, and three brigades of the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) guerrillas. The Ethiopian defense—the 78th Brigade, the 7th Infantry Battalion, the 216th Battalion, and the 752nd Battalion—were enormously outnumbered and outgunned by the Somalis. The battle raged until 11:00 hours, and the Somalis pushed the defenders to the outskirts of the city; the outcome of the battle for the strategic city would prove critical. Not only was Ethiopia's second largest air base located there, but the city represented both its crossroads into the Ogaden and rail lifeline to the Red Sea. At that critical moment, reinforcements arrived from Harar. With close air support, the troops from Harar helped the defenders drive the Somalis back twenty kilometers from the city. Around the same time, the Ethiopian Air Force (ETAP) also began to establish air superiority using its Northrop F-5s, despite initially being outnumbered by Somali MiG-21s. Even though the Somalis possessed more aircraft (53 to 36) during the initial months of the war, they were outmatched by the Ethiopian Air Force. The Ethiopians not only attained near-absolute control over their own skies but also managed to breach Somali airspace, reaching as far as the city of Berbera and destroying 9 MiG-17s and 18 MiG-21s in the air and another 6 on the ground within Somali territory.[106] Due to a serious shortage spare parts, the Somali Air Force remained grounded throughout most the war and anti-aircraft equipment was in short supply.[82]

Following the relatively easy capture of Delo, Elekere, and Filtu by August 8, the Somalis seemed to be strategically positioned to attain their objective of liberating the Ogaden by December. Dire Dawa, an important industrial city of 70,000 inhabitants, was now in their sights. On August 17, the Somalis launched an assault against Dire Dawa. The Somalis advanced on the city with 2 motorized brigades, 1 tank battalion and 1 BM-13 battery. Facing these were the Ethiopian 2nd Division, the 201st battalion, the 781st battalion, the 4th Mechanized Company, and a tank platoon with two tanks. On August 17 the Somalis advanced from Harewa to the northeastern part of the city at night. Despite losing three tanks to landmines en route, they launched a ground assault the following day. The 781st battalion held out in Shinile for several hours before being forced to retreat to the city. As the Somalis closed in on the city they began shelling it with artillery. A Somali tank battalion managed to push through and temporarily made the country's second major airport non-operational; the air traffic control and as many as 9 aircraft on the ground were destroyed. For the next 20 hours, the Ethiopians and the Somalis engaged in a fierce battle until the Ethiopian air force began to relentlessly pound the enemy, destroying 16 T-55s. The Somalis had exhausted their strength were forced to retreat, leaving behind a trail of abandoned equipment, including tanks, armored cars, artillery pieces, as well as hundreds of assault rifles and machine guns.[107]

The Soviet Union, finding itself allied to both sides of the war, attempted to mediate a ceasefire. While the Ethiopians was fighting hard to stop the Somali advances, Mengistu Haile Mariam kept on pressing the Soviets to deliver arms to Ethiopia. The Soviets responded in the affirmative: they supplied Ethiopia with substantial weapons such artillery and tanks in early September 1977. Two weeks later, the Derg received other good news: the termination of Soviet arms delivery to Somalia. The Soviets were thus committed to helping Ethiopia. Beginning at the final week of September, the Soviets supplied Ethiopia with T-55 tanks, rocket launchers, and MiG-21 fighter planes, a Soviet military airlift with advisors for Ethiopia took place (second in magnitude only to the colossal October 1973 resupplying of Syrian forces during the Yom Kippur War), alongside 15,000 Cuban combat troops in a military role. South Yemen sent in late September two armored battalions to Ethiopia. On November 13 Somalia ordered all Soviet advisers to leave the country within seven days, ended Soviet use of its strategic naval facilities and also broke diplomatic relations with Cuba.[108][109] Soviet advisors fulfilled a number of roles for the Ethiopians from this point forward. While the majority included training and headquarters operations, some flew combat mission in MiGs and helicopters.[110]

Other communist countries like South Yemen and North Korea offered Ethiopia military assistance.[108] East Germany offered training, engineering and support troops.[5] Israel reportedly provided cluster bombs, napalm and were also allegedly flying combat aircraft for Ethiopia.[111][112] Not all communist states sided with Ethiopia. Because of the Sino-Soviet rivalry, China supported Somalia diplomatically and with token military aid.[113][114] Romania under Nicolae Ceauşescu had a habit of breaking with Soviet policies and also maintained good diplomatic relations with Barre.

Somali victories and siege of Harar (September–January)

The greatest single victory of the SNA-WSLF was the assault on Jijiga in mid-September 1977. Undaunted by their setback at Dire Dawa, the reinforced Somalis redirected their efforts towards the third-largest provincial town. On September 2, they launched a forceful attack, employing artillery, mortar, and tanks. A renewed and more resolute offensive took place on September 9, as the Somalis relentlessly bombarded Ethiopian positions with rockets and artillery shells. Adding to the challenges, Somali fire managed to destroy the radar atop Mount Karamara, diminishing the Ethiopian air force's ability to provide essential close air support. This event prompted a large-scale retreat to Adaw. As the Somalis intensified their artillery shelling on Adaw, the army conducted a full retreat to Kore. On September 12, 1977, Jijiga fell into the hands of the Somalis. Worse still, on September 13, Marda Pass on Mount Karamara, of huge strategic importance, fell into Somali hands, By September, Ethiopia was forced to admit that it controlled only about 10% of the Ogaden and that the Ethiopian defenders had been pushed back into the non-Somali areas of Harerge, Bale, and Sidamo.[115]

The retreating Ethiopian forces eventually came to a halt at Kore, positioned midway between Jijiga and Harar. Amidst the falling Somali artillery shells, panic once again gripped the soldiers at Kore. The 3rd Division, which had established its headquarters at Kore, responded to the retreat with harsh measures, ordering the air force to strike friendly forces if they retreated. These setbacks were promptly attributed to "fifth columnists," leading to the execution of several officers and NCOs for alleged conspiracy with "anarchists"—primarily leftist political organizations, particularly the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP). Despite this, it did not spare the commander of the 3rd Division from criticism from his superiors. Mengistu Haile Mariam told him to redeem himself for the fall of Karamara by establishing a defensive line at Kore, and by eventually recapturing the Pass. At this point, the government called for a general mobilization. From September 14 to 21, Mengistu issued several directives for mobilization using the slogans "everything to the warfront" and "revolutionary motherland or death".[116]

Following the capture of Jijiga and Karamara, a one-week pause in fighting ensued. During this period, Mengistu formulated a novel operational strategy named "Awroa" to the Eastern Command, which he subsequently reorganized into the Dire Dawa and Harar sectors. Operation Awrora aimed to thwart Somalia's strategic objectives by resolutely defending the cities of Dire Dawa and Harar. In the latter part of September, the Somali offensive experienced a rapid decline, attributed to adverse weather conditions, challenging terrain, and exhaustion among their forces. The initial Somali blitzkrieg concluded, marking the commencement of an attrition phase. Losing their momentum, the Somalis provided an opening for the Ethiopians to regroup their troops, introduce fresh units and additional weaponry, and construct bunkers on the hillsides.[116]

The Somalis then launched an offensive, advancing towards the east toward Harar. Their primary aim was on penetrating the eastern front line, pushing forward from Karamara and Fik. Despite the weak position of the Ethiopian defense line, it took the Somalis over seven weeks to breach it. Beginning at the end of September, the Soviets supplied Ethiopia with significant arms, such as aircraft and tanks. Additionally, as the Ethiopian army gained more combat experience, they became more experienced with their new Soviet weaponry. Although the Somalis enjoyed full support in the Ogaden, the highland population, vehemently opposed the Somalis and provided unwavering support to the Ethiopian army in various ways, ranging from scouting to guarding strategic crossroads. As the Somalis advanced further into hostile territories, their stretched lines became increasingly susceptible to disruption.[117]

Over a span of four months, from the last week of September to the middle of December, the Somalis exerted considerable effort to seize Harar. On two occasions, it appeared that the city, with its forty-eight thousand inhabitants and as the home of Ethiopia's foremost military academy, was on the brink of falling. However, Harar did not surrender, primarily due to the relatively slow and indecisive operational maneuvers of the Somalis and the arrival of Soviet weapons in late October. The Ethiopians were bolstered by deployment of 100,000 recently trained troops outfitted in new Soviet gear, around 30,000 of them, referred to as the "1st Revolutionary Liberation Army", were subsequently sent to the Somali front. By December, the exhausted Somali forces were forced to withdraw to Fedis, Jaldessa and Harewa, where they had to await the Ethiopian counterattack. At this point came the regular Cuban troops, with only a few hundred in December, they eventually grew to three thousand in January to 16,000 in February. They were armed with full Soviet gear, including T-62 tanks, artillery, and APCs. The Somalis had gambled by cutting off the Russians and Cubans; now they stood virtually alone against an multinational colossus.[118][34]

Ethiopian-Cuban counterattack (February–March)

In January 1978, the Derg established the Supreme Military Strategic Committee (or SMSC), composing of Ethiopian, Soviet, and Cuban officers to plan and direct the counter-offensive. The Committee was led by General Vasily Petrov, the deputy commander of the Soviet Ground Forces. The operation marked was painstakingly planned and well-directed. Its key elements included surprise artillery barrages, which were followed by subsequent mass infantry and mechanized assaults, drawing inspiration from Soviet assault tactics.[119] Petrov was unwilling to trust Ethiopian troops, instead opting to use a Cuban parachute regiment to spreadhead operations.[120] The main force for the counter offensive consisted of three Cuban infantry regiments, their tank regiment, most of their artillery and two divisions of Ethiopian troops. The flanking force was composed of the Cuban paratroop regiment, several battalions of their artillery and one Ethiopian division. Heavy usage of close air support and air strikes were a hallmark of the operation.[121] At their peak, 17,000 Cuban army troops took part in the offensive.[122]

The counter-offensive was preceded by an ambitious Somali attempt to capture Harar on January 22. The Somalis initiated their plan by launching mortar and rocket attacks on the town of Babile from Hill 1692, with the apparent intention of diverting Ethiopian attention. At 15:30 hours, multiple Somali infantry brigades, supported by a substantial number of tanks advanced toward Harar from Fedis and Kombolcha. In a coordinated ground and air resistance involving Cuban soldiers for the first time, the Ethiopians engaged the Somalis a few miles from Harar; they launched a series of sharp thrusts against the attackers, pinning them down. While a ground battle with tanks unfolded, jet fighter-bombers attacked the enemy's rear and communication lines. The Somalis suffered a significant defeat, with casualties possibly reaching as high as 3,000—their most significant loss since the war began. Following this success, the Ethiopians shifted from a defensive to an offensive stance. From January 23 to 27, the Ethiopian 11th Division and the Cuban armored units were able to recapture all territory up to Fedis. In the process, they captured 15 tanks, numerous APCs, 48 artillery guns, 7 anti-aircraft guns, numerous infantry weapons, and various munitions.[119]

The Ethiopian-Cuban counterattack began on February 1, the Ninth Division headed by Cuban shock troops attacked the Somalis in Harewa, immediately forcing them to retreat, the attackers then moved north and captured Jaldessa on the 4th. By February 9th, the Somalis fled from the towns of Chinaksen, Ejersa Goro, and Gursum, leaving behind 42 tanks, numerous APCs, and over 50 artillery guns.[123] Artillery, notably BM-21 rocket launchers, along with close air support were crucial in winning the battle. As a result the Somalis decided to withdraw to their prepared defensive positions in the Kara Marda Pass.[121] A column of Ethiopian and Cuban troops then crossed northeast into the highlands between Jijiga and the border with Somalia, bypassing the SNA-WSLF force defending the Marda Pass. The responsibility for the task was assigned to the Tenth Division, which relied on a Cuban tank brigade with over 60 T-62 tanks. On February 15, they maneuvered around the impregnable Marda Pass, opting for a detour through Arabi and advancing towards the Shebele Pass, successfully capturing it on the 24th. Despite strong Somali resistance at Grikocher, the town was eventually secured on the 28th.[123]

Second battle of Jigjiga (March 1978)

Jigjiga was a pivotal point in the Somali defensive line and had major political significance to Mengistu as it had represented the site of the Ethiopians greatest defeat the previous autumn. 8,000 Somali army troops, composed of one T-55 tank battalion and one 122 mm artillery battalion, were dug in around Jigjiga and the surrounding Kara Marda Pass. Fierce engagements in mid-February near Babile in the mountains resulted in heavy Ethiopian casualties, and as a result Soviet General Vasily Petrov realized that a direct attack on the Somalis holding Jigjiga and the pass would be an highly costly operation. Petrov decided to get around the issue by deploying some of his forces via airlift in the plains behind Jigjiga. To this end, the Cubans formed their paratroopers into a special airmobile units. 20 Mil-8 and 10 Mil-6 helicopters, flow by Soviet pilots, were to be used in the operation to break the back of the Somali army.[120] Conventional aircraft also assisted the airdrop operation as the helicopters prepared to deploy a battalion with armored vehicles.[121]

From this point onward, the advance to Jijiga was led by the 69th Brigade, the forward units reached the western side of the mountains around Jijiga on February 28. The Somalis stationed at Jijiga attacked the Ethiopians on the mountain range, but were pinned down due to unremitting airstrikes.[123] The Cuban air deployment behind the Somali forces at Jigjiga came in three waves of combined helicopter and parachute operations beginning during the last few days of February 1978.[121] Ethiopian 1st Paracommando Brigade also, participated and the operation laid the groundwork for the ultimate attack on the town. The 10th Division and its Cuban shock troops advanced towards Jijiga, while the Ethiopian 75th Infantry Brigade and the 1st Paracommando Brigade took a southerly route through the mountains to seize the Marda Pass.[123]

On 2 March, a combine parachute/heliborne attack was made on the Somalis, who were driven back south. Around the same time, the Djibouti-Addis railway was cleared. Another major airmobile operation took place on 5 March 1978, providing the spearhead for the rear attack on Jigjiga. Around 100 Mil-6 helicopter sorties were made in this period to drop heavy equipment. From the landing zone, this task force drove onto Jigjiga and attacked the Somali troops defending Jigjiga from the rear. The rear attack by the Cubans coincided with a frontal assault by the main Ethiopian/Cuban force on Jigjiga.[121] Under the weight of the combined rear and frontal attack the Somali defence collapsed.[123] Six Somali brigades in the garrison valiantly fought for three days against overwhelming odds. Hindered by the absence of air cover, dwindling supplies, and tank strength possibly below 50 percent, they were forced to retreat on March 5, narrowly avoiding an encirclement. The Somalis lost as many as 3,000 men, whereas Ethiopian and Cuban casualties were apparently very light.[123] Ethiopian troops conducted mop up operations, but the effective victors of the 2nd Battle of Jigjiga had been the Cubans.[34] Cuban troops and aircraft had provided the main strength of the rear attack that had ultimately broken Somali resistance.[124]

Somali army withdrawal

The war was effectively concluded with the recapture of Jijiga on March 5. Mengistu Haile Mariam, buoyed by the retaking of Karamara and Jijiga, had been deeply horrified by their capture six months prior. In a statement praising the Eastern Command for their efforts, he expressed, "This marks not just a victory for the Ethiopian people but also for the struggles of the workers of the world."[125] Recognizing that his position was untenable, Siad Barre ordered the SNA to retreat into Somalia on 9 March 1978, although Rene LaFort claims that the Somalis, having foreseen the inevitable, had already withdrawn their heavy weapons.[125] As the Somali army withdrew, the Ethiopians and the Cubans immediately began a general offensive. A column comprising the Ethiopian 3rd Division and the 3rd Cuban Tank Brigade effortlessly captured Degehabur on March 8. Meanwhile, to the west, Somali forces unexpectedly resisted the 8th Division's advance towards Fik. During this engagement, the Ethiopian 94th Brigade suffered severe losses at Abusharif, leading its commander, Major Bekele Kassa, to take his own life rather than face capture. Despite this setback, the Division, reinforced by a Cuban battalion, pressed on and covered a distance of 150 kilometers to reach Fik on March 8.[125] The fall of Jigjiga to the Ethiopian/Cuban forces was the culmination of the war, and it was followed by three weeks of frantic withdrawal by the Somali National Army. In one of the final actions of the war, American military historian Jonathan House observes that the Somalis had "fought a brilliant delaying battle, mauling the Ethiopian 9th brigade."[126]

Post war

Executions and rape of civilians and refugees by Ethiopian and Cuban troops were prevalent throughout the war.[127][128] A large Cuban contingent remained in Ethiopia after the war to protect the Ethiopian government.[127]

Throughout the late 1970s, internal unrest in the Ogaden region continued as the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) waged a guerrilla war against the Ethiopian government. After the war, an estimated 800,000 people crossed the border into Somalia where they would be displaced as refugees for the next 15 years. The defeat of the WSLF and Somali National Army in early 1978 did not result in the pacification of the Ogaden.[129] At the end of 1978 the first major outflow of refugees numbering in the hundreds of thousands headed for Somalia, and were bombed and strafed during the exodus by the Ethiopian military. During 1979, the Western Somali Liberation Front persisted in its resistance, regaining control of rural areas.[130]

Assisted by the Cuban contingent, the Ethiopian army launched a second offensive in December 1979 directed at the population's means of survival, including the poisoning and destruction of wells and killing of cattle herds. Thousands of Somali civilians in the Ogaden were killed. Combined with the flight of several hundred thousand refugees into Somalia, this represented an attempt to pacify the region with brute force. Around half of the population in the Ogaden were displaced to Somalia, some diplomats referred to the depopulation in the Ogaden as a genocide.[128] Ethiopian forces also attacked Harari and Oromo civilians in the neighboring regions claiming they were collaborators.[131]

Foreign correspondents who visited the Ogaden during the early 1980s noted widespread evidence of a 'dual society', with the Somali inhabitants of the region strongly identified as 'Western Somalis'. Artificial droughts and famine were induced by the Derg regime to break down Somali opposition to Ethiopian rule in the Ogaden.[132] In the early 1980s the Ethiopian government rendered the region a vast military zone, engaging in indiscriminate aerial bombardments and forced resettlement programs.[133] During 1981 there were an estimated 70,000 Ethiopian troops in the Ogaden, supported by 10,000 Cuban army troops who garrisoned the regions towns.[134] By May 1980, the rebels, with the assistance of a small number of SNA soldiers who continued helping their guerrilla war, controlled a large part of the Ogaden region. It took a massive counter-insurgency campaign to clear the region of guerrillas by 1981, although the insurgency continued until the mid-1980s. The WSLF was practically defunct by the mid-1980s, and its splinter group, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), operated from headquarters in Kuwait. Even though elements of the ONLF would later manage to slip back into the Ogaden, their actions had little impact.[135]

For the Barre regime, the invasion was perhaps the greatest strategic blunder since independence,[136] and it greatly weakened the military. Almost one-third of regular SNA soldiers, three-eighths of its armored units, and half of the Somali Air Force (SAF) were lost. The weakness of the Barre administration led it to effectively abandon the dream of a unified Greater Somalia. The failure of the war aggravated discontent with the Barre regime; the first organized opposition group, the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), was formed by army officers in 1979.

The United States adopted Somalia as a Cold War ally from the late 1970s to 1988 in exchange for use of Somali bases it used for access to the Middle East, and as a way to exert influence in the Horn of Africa.[137] A second armed clash in 1988 between Somalia and Ethiopia ended when the two countries agreed to withdraw their armed forces from the border.

Refugee crisis

Somalia's defeat in the war caused an influx of Ethiopian refugees (mostly ethnic Somalis as well as some Harari and Oromo)[138] across the border to Somalia. By 1979, official figures reported 1.3 million refugees in Somalia, more than half of them settled in the lands of the Isaaq clan-family in the north. According to a 1979 report from The New York Times refugees were also held in southern Somalia which consisted of 200,000 Hararis and 100,000 Oromo.[139] As the state became increasingly reliant on international aid, aid resources allocated for the refugees caused further resentment from local Isaaq residents, especially as they felt no effort was made on the government's part to compensate them for bearing the burden of the war.[140]

Furthermore, Barre heavily favoured the Ogaden refugees, who belonged to the same clan (Darod) as him. Due to these ties, Ogaden refugees enjoyed preferential access to "social services, business licenses and even government posts."[140] As expressed animosity and discontent in the north grew, Barre armed the Ogaden refugees, and in doing so created an irregular army operating inside Isaaq territories. The armed Ogaden refugees, together with members of the Marehan and Dhulbahanta soldiers (who were provoked and encouraged by the Barre regime) started a terror campaign against the local Isaaqs,[141] raping women, murdering unarmed civilians, and preventing families from conducting proper burials.

Barre ignored Isaaq complaints throughout the 1980s.[141] This, in addition to Barre's suppression of criticism or even discussion of widespread atrocities in the north,[141] had the effect of turning long-standing Isaaq disaffection into open opposition, with many Isaaq forming the Somali National Movement, leading to the ten-year civil war in northwestern Somalia (today the de facto state of Somaliland).[142]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". The RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 42–46. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524. ISSN 0307-1847.

Soviet advisers fulfilled a number of roles, although the majority were involved in training and headquarters duties. Others flew combat missions in the MiGs and helicopters.

- ^ "Ogaden Area recaptured by Ethiopian Forces with Soviet and Cuban Support – International Ramifications of Ethiopian-Somali Conflict – Incipient Soviet and Cuban Involvement in Ethiopian Warfare against Eritrean Secessionists – Political Assassinations inside Ethiopia". Keesing's Record of World Events (formerly Keesing's Contemporary Archives). 1 May 1978. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Lefebvre, Jeffrey Alan. Arms for the horn : U.S. Security Policy in Ethiopia and Somalia. University of Pitsburg Press. p. 188. OCLC 1027491003.

- ^ "Arms and Rumors From East, West Sweep Ethiopia". Washington Post. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Ethiopia: East Germany". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2004-10-29.

- ^ Prentis Woodroofe, Louise (1994). "Buried in the Sands of the Ogaden: The United States, The Horn of Africa and The Demise of Detente" (PDF). London School of Economics and Political Science.

- ^ "North Korea's Military Partners in the Horn". The Diplomat. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Mekonnen, Teferi (2018). "The Nile issue and the Somali-Ethiopian wars (1960s–78)". Annales d'Éthiopie. 32: 271–291. doi:10.3406/ethio.2018.1657.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald, Nina J. (2002). Somalia; Issues, History, and Bibliography. Nova Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 978-1590332658.

- ^ Malovany, Pesach (2017). Wars of Modern Babylon. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813169453.

- ^ a b Tareke 2000, p. 656.

- ^ Ayele 2014, p. 106: "MOND classified documents reveal that the full-scale Somali invasion came on Tuesday, July 12, 1977. The date of the invasion was not, therefore, July 13 or July 23 as some authors have claimed."

- ^ Tareke 2000.

- ^ Gorman 1981, p. 208.

- ^ Tareke 2009, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Tareke 2000, p. 638.

- ^ a b c Ayele 2014, p. 105.

- ^ Gleijeses, Piero (2013). Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976–1991. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4696-0968-3.

- ^ White, Matthew (2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08330-9.

- ^ South Yemen's Revolutionary Strategy, 1970–1985. Routledge. 2019. ISBN 978-1000312294.

- ^ Dixon, Jeffrey S.; Sarkees, Meredith Reid (2015). A Guide to Intra-state Wars. ISBN 978-0872897755.

- ^ a b Tareke 2000, p. 640.

- ^ Tareke 2000, p. 663.

- ^ Muuse Yuusuf (2021). Genesis of the civil war in Somalia. London: I.B. Tauris. OCLC 1238133342.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tareke 2000, p. 665.

- ^ a b c Ayele 2014, p. 123.

- ^ a b c "La Fuerza Aérea de Cuba en la Guerra de Etiopía (Ogadén) • Rubén Urribarres". Aviación Cubana • Rubén Urribarres.

- ^ a b c d "ТОТАЛЬНАЯ СОЦИАЛИСТИЧЕСКАЯ ВОЙНА. НЕДОКУМЕНТАЛЬНЫЕ ЗАПИСКИ: Война между Эфиопией и Сомали 1977–78 гг. Page 2". Archived from the original on 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ "68. Ethiopia/Ogaden (1948-present)". UCA. 1948-07-24. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ a b c d e Ayele 2014, p. 124.

- ^ "4. Insurrection and Invasion in the Southeast, 1962–78" (PDF). Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-26.

- ^ Evil days: thirty years of war and famine in Ethiopia. New York: Human Rights Watch. 1991. ISBN 978-1564320384 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Tareke 2009, p. 186.

- ^ a b c Clodfelter 2017, p. 557.

- ^ Pollack, Kenneth Michael (2019). Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–91.

- ^ Tareke 2000, p. 660.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of Somalia". stratfor.com. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Abdi, Said Y. (January–March 1978). "Self-Determination for Ogaden Somalis". Horn of Africa. 1 (1): 20–25.

- ^ FitzGibbon, Louis (1985). The Evaded Duty. R. Collings. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-86036-209-8.

- ^ FitzGibbon 1985, p. 29.

- ^ Abdi 2021, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Woodward, Peter; Forsyth, Murray (1994). Conflict and peace in the Horn of Africa : federalism and its alternatives. Dartmouth: Aldershot. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-1-85521-486-6.

- ^ Irons, Roy (2013-11-04). Churchill and the Mad Mullah of Somaliland: Betrayal and Redemption 1899-1921. Pen and Sword. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-78346-380-0.

- ^ Geshekter, Charles L. (1979). "Socio-Economic Developments in Somalia". Horn of Africa. 2 (2): 24–36.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1983, p. 157–159.

- ^ Laitin, David D.; Samatar, Said S. (1987). Somalia: Nation In Search Of A State. Avalon Publishing. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-0-86531-555-6.

- ^ Woodward, Peter; Forsyth, Murray (1994). Conflict and peace in the Horn of Africa : federalism and its alternatives. Dartmouth: Aldershot. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-1-85521-486-6.

- ^ a b Drysdale 1964, p. 56.

- ^ Greenfield, Richard (1979). "An Historical Introduction to Refugee Problems in the Horn". Horn of Africa. 2 (4): 14–26.

- ^ Woodward, Peter; Forsyth, Murray (1994). Conflict and peace in the Horn of Africa : federalism and its alternatives. Dartmouth: Aldershot. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-1-85521-486-6.

- ^ a b c d Abdi, Said Y. (January–March 1978). "Self-Determination for Ogaden Somalis". Horn of Africa. 1 (1): 20–25.

- ^ Madan Sauldie (1987). Super powers in the Horn of Africa. p. 48. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Geshekter, Charles L. (1979). "Socio-Economic Developments in Somalia". Horn of Africa. 2 (2): 24–36.

- ^ a b Drysdale 1964, p. 65.

- ^ Davids, Jules (1965). The United States in world affairs, 1964. New York : Published for the Council on Foreign Relations by Harper & Row. pp. 284–286 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Drysdale 1964, p. 70-71.

- ^ Federal Research Division, Somalia: A Country Study, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p. 38

- ^ Zolberg, Aristide R.; et al. (1992). Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World. Oxford University Press. p. 106. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Abdi, Said Y. (January–March 1978). "Self-Determination for Ogaden Somalis". Horn of Africa. 1 (1): 20–25.

- ^ Geshekter, Charles L. (1979). "Socio-Economic Developments in Somalia". Horn of Africa. 2 (2): 24–36.

- ^ a b "The 1963 Rebellion in the Ogaden". Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Somali Studies. Vol. II: Archaeology and History. Helmut Buske Verlag. 1984. pp. 291–307. ISBN 3-87118-692-9.

- ^ Abdi 2021, p. 75.

- ^ Hagmann, Tobias (2014-10-02). "Punishing the periphery: legacies of state repression in the Ethiopian Ogaden". Journal of Eastern African Studies. 8 (4): 725–739. doi:10.1080/17531055.2014.946238. ISSN 1753-1055.

- ^ a b Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. Taylor & Francis. 2017. pp. 191–192. ISBN 9781317539520.

- ^ Greenfield, Richard (1979). "An Historical Introduction to Refugee Problems in the Horn". Horn of Africa. 2 (4): 14–26.

- ^ Henze, Paul B.; Corporation, Rand (1986). Rebels and Separatists in Ethiopia: Regional Resistance to a Marxist Regime. Rand. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8330-0696-7.

- ^ Abdi 2021, p. 84.

- ^ "Somali Support for Ogadenis Wanes". Africa Confidential. 25: 5–7. 17 October 1984.

- ^ Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p. 290.

- ^ Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Ford, Richard (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56902-073-6.

- ^ J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 8, (Cambridge University Press: 1985), p. 478. [ISBN missing]

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac, Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p. 214.

- ^ Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy, (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p. 279 ISBN 0-7099-2709-6.

- ^ Crockatt 1995, pp. 283–285.

- ^ a b Abdi 2021, p. 93-94.

- ^ Fitzgibbon, Louis (1982). The Betrayal of the Somalis. R. Collings. pp. 52–54. ISBN 9780860361947.

- ^ Erlich, Haggai (March 2010). "6 Nationalism and Conflict: Ethiopia and Somalia, 1943–1991". Islam and Christianity in the Horn of Africa. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 152. doi:10.1515/9781588269874-007. ISBN 978-1-58826-987-4.

On 15 January 1976, supported and inspired by the Saudi Muslim World League, the WSLF was reorganized. Some of its Oromo members, headed by the veteran leader of the 1965–1970 Oromo rebellion in the Bale region, Wako Guto, declared the establishment of a sister movement called the Somali Abbo Liberation Front (SALF). Under the guise of a Somali identity (Wako Guto's father was an Oromo and his mother a Somali), it was an overtly Oromo-Islamic movement which extended its operations to the provinces of Bale, Arusi, and Sidamo. For all intents and purposes, the Oromos, whether Christian or Muslim, never intended to become Somalis. Oromos and Somalis are not natural allies and have in fact been rivals over most of modern history because Oromos in the south and east of Ethiopia gradually moved toward Somali-dominated areas. However, what was now in the making was an all-Islamic movement, complete with the participation of Harari Islamic activists of Adari origin, already associated with the WSLF and trained in the Arab Middle East, with Somali and Saudi help. They now joined forces with the WSLF and the SALF and all coordinated their anti-Ethiopian guerrilla activities from late 1976. The Harari-Adari fighters called themselves the "Ahmad Gragn Forces," and indeed, nothing could have been more similar to Ahmad Gragn's movement to unite Muslims in all of southeastern Ethiopia through an Islamic holy war.

- ^ Woldemariam, Michael (2018). Insurgent Fragmentation in the Horn of Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Gorman 1981, p. 59.

- ^ Tareke, Gebru (2016). The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa. Eclipse Printing Press. p. 642. ISBN 978-99944-951-2-2. OCLC 973809792.

- ^ a b Abdul Ahmed III (29 October 2011). "Brothers in Arms Part I" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". The RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 42–46. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524. ISSN 0307-1847.

- ^ Lewis, I.M.; The Royal African Society (October 1989). "The Ogaden and the Fragility of Somali Segmentary Nationalism". African Affairs. 88 (353): 573–579. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098217. JSTOR 723037.

- ^ Lockyer, Adam. "Opposing Foreign Intervention's Impact on the Course of Civil Wars: The Ethiopian-Ogaden Civil War, 1976–1980" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Payne, Richard J. (1988). Opportunities and Dangers of Soviet-Cuban Expansion: Toward a Pragmatic U.S. Policy. SUNY Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0887067969.

- ^ Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part II" (PDF). WardheerNews. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Ogaden War, 1977–1978". Air Combat Information Group. Archived from the original on 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ Cooper 2015, p. 31.

- ^ De Waal 1991, p. [page needed].

- ^ Letter from Jeddah: An interview with the WSLF (PDF). Horn of Africa Journal. p. 7.

- ^ Matshanda, Namhla (2014). Centres in the Periphery: Negotiating Territoriality and Identification in Harar and Jijiga from 1942 (PDF). The University of Edinburgh. p. 200. S2CID 157882043. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-31.

- ^ De Waal 1991, p. iv.

- ^ Harff, Barbara; Gurr, Ted Robert (1988). "Toward an Empirical Theory of Genocides and Politicides". International Studies Quarterly. 32 (3): 364.

- ^ US admits helping Mengistu escape BBC, 22 December 1999

- ^ "Genocides, Politicides, and Other Mass Murder Since 1945, With Stages in 2008". Genocide Prevention Advisory Network. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Which is Better, the F-5E Tiger II or the MiG-21?". War is boring. 8 August 2016.

- ^ Mekonnen Beri, Aviation in Ethiopia (Addis Ababa: Nigid Printing Press, 2002), p. 100

- ^ a b c d e Schaefer, Scoot. "Ethiopian Airpower:From Inception to Victory in the Ogaden War".

- ^ a b c Abdi 2021, pp. 100–112.

- ^ a b Maruf, Harun (26 November 2016). "Fidel Castro Left Mark on Somalia, Horn of Africa". Voice of America. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ a b c Sheikh, Mohamed Aden (2010). Petrucci, Pietro (ed.). La Somalia non è un'isola dei Caraibi : Memorie di un pastore somalo in Italia (in Italian). Diabasis. pp. 111–119. ISBN 9788881037063. OCLC 662402642.

- ^ Abdi, Said Y. (January–March 1978). "Self-Determination for Ogaden Somalis". Horn of Africa. 1 (1): 20–25.

But the so called conciliation, more of a soviet imposed solution, essentially involved Somalia giving up the Ogaden. Siad turned this down since he could not speak for the WSLF.

- ^ Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". The RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 43. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524. ISSN 0307-1847.

- ^ a b Tareke 2000, p. 644.

- ^ a b Ayele 2014, p. 106.

- ^ Tareke 2000, p. 645.

- ^ Tareke 2000, p. 646.

- ^ a b & Mekonnen 2013, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Ayele 2014, p. 113.

- ^ Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". The RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 42–46. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524. ISSN 0307-1847.

Soviet advisers fulfilled a number of roles, although the majority were involved in training and headquarters duties. Others flew combat missions in the MiGs and helicopters.

- ^ Lefebvre, Jeffrey Alan (1991). Arms for the horn : U.S. Security Policy in Ethiopia and Somalia, 1953–1991. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 188. ISBN 0-8229-8533-0. OCLC 1027491003.

- ^ Mann, Roger (1977-08-12). "Arms and Rumors From East, West Sweep Ethiopia". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ "Russians in Somalia: Foothold in Africa Suddenly Shaky". New York Times. 1977-09-16. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ "the ogaden situation" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 23, 2017. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ Ayele 2014, p. 109.

- ^ a b Tareke 2000, p. 648.

- ^ Tareke 2000, p. 649.

- ^ Tareke 2009, p. 205.

- ^ a b Tareke 2000, p. 657.

- ^ a b Perrett, Bryan (2020-12-10). Seize and Hold. Orion. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-4746-1916-5.

After the northern end of the Somali line had been unhinged by a series of parachute and air-landing operations involving twenty Mil-8 and ten Mil-6 helicopters flown by Soviet pilots, Petrov decided to break the back of the enemy's resistance by capturing the stronghold of Jigjiga, using the same means.

- ^ a b c d e Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". The RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 45. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524. ISSN 0307-1847.

- ^ Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". The RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 44. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524. ISSN 0307-1847.

- ^ a b c d e f Tareke 2000, p. 659.

- ^ Porter, Bruce D. (1986-07-25). The USSR in Third World Conflicts: Soviet Arms and Diplomacy in Local Wars 1945-1980. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-31064-2.

- ^ a b c Lefort 1983, p. 260.

- ^ House, Jonathan M. (2020-09-24). A Military History of the Cold War, 1962–1991. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-6774-9.

- ^ a b Clapham, Christopher (1990). Transformation and Continuity in Revolutionary Ethiopia. CUP Archive. p. 235.

- ^ a b De Waal 1991, pp. 78–86.

- ^ Hagmann, T.; Khalif, Mohamud H. (2008). "State and Politics in Ethiopia's Somali Region since 1991". Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies. S2CID 54051295.

- ^ "Ogaden: The Land But Not the People". Horn of Africa. 4 (1): 42–45. 1981.

- ^ Selassie, Bereket (1980). Conflict and Intervention in the Horn of Africa. Monthly Review Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-85345-539-4.

- ^ "Ogaden: The Land But Not the People". Horn of Africa. 4 (1): 42–45. 1981.

- ^ Hagmann, T.; Khalif, Mohamud H. (2008). "State and Politics in Ethiopia's Somali Region since 1991". Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies. S2CID 54051295.

- ^ "Ethiopia: Conquest and Terror". Horn of Africa. 4 (1): 8–19. 1981.

- ^ Belete Belachew Yihun (2014). "Ethiopian foreign policy and the Ogaden War: the shift from "containment" to "destabilization," 1977–1991". Journal of Eastern African Studies. 8 (4): 677–691. doi:10.1080/17531055.2014.947469. S2CID 145481251. The version at samaynta.com lacks references.

- ^ Tareke 2009, p. 214.

- ^ Oberdorfer, Don (5 March 1968). "The Superpowers and the Ogaden War". Washington Post.

- ^ Mohamoud, Abdullah A. (1 January 2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960–2001). Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- ^ Jaynes, Gregory (19 November 1979). "Ogaden Refugees Overwhelming Somali Resources". The New York Times. NY times. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b Richards, Rebecca (24 February 2016). Understanding Statebuilding: Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-00466-0.

- ^ a b c Janzen, Jörg; Vitzthum, Stella von (2001). What are Somalia's Development Perspectives?: Science Between Resignation and Hope?. Proceedings of the 6th SSIA Congress, Berlin 6–9 December 1996. Verlag Hans Schiler. ISBN 978-3-86093-230-8.

- ^ Law, Ian (2013-09-05). Racism and Ethnicity: Global Debates, Dilemmas, Directions. Routledge. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-317-86434-9.

Bibliography

- Ayele, Fantahun (2014). The Ethiopian Army: From Victory to Collapse, 1977–1991. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0810130111.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Cooper, Tom (2015). Wings over Ogaden: The Ethiopian-Somali War (1978–1979). Africa @ War. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1909982383.

- Crockatt, Richard (1995). The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in World Politics. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10471-5. OCLC 123491949.

- De Waal, Alexander (1991). Evil days: thirty years of war and famine in Ethiopia. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-038-3. OCLC 24504262.

- Gorman, Robert F. (1981). Political Conflict on the Horn of Africa. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-030-59471-7.

- Lefort, René (1983). Ethiopia: An Heretical Revolution?. London: Zed Press. ISBN 978-0-862-32154-3.

- Mekonnen, Yohannes K. (2013). Ethiopia: The Land, Its People, History and Culture. New Africa Press. ISBN 978-9987160242.

- Tareke, Gebru (2000). "The Ethiopia-Somalia War of 1977 Revisited" (PDF). International Journal of African Historical Studies. 33 (3): 635–667. doi:10.2307/3097438. JSTOR 3097438. S2CID 159829531.

- ——— (2009). The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14163-4.

- Lewis, ed. (1983). Nationalism & Self Determination in the Horn of Africa (I.M. ed.). Ithaca Press. ISBN 978-0-903729-93-2.

- Drysdale, John (1964). The Somali Dispute. Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 467147.

- Abdi, Mohamed Mohamud (2021). A History of the Ogaden (Western Somali) Struggle for Self-Determination: Part I (1300–2007) (2nd ed.). UK: Safis Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906342-39-5.

Further reading

- Halliday, Fred; Molyneux, Maxine (1982). "Ethiopia's Revolution from Above". MERIP Reports (106): 5–15. doi:10.2307/3011492. JSTOR 3011492.

- Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46791-7.

- Mitchell, Nancy (2016). Jimmy Carter in Africa: Race and the Cold War. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804793858.

External links

- Ogaden War

- Cold War conflicts

- Cold War in Africa

- Conflicts in 1977

- Conflicts in 1978

- 1977 in Ethiopia

- 1977 in Somalia

- 1978 in Ethiopia

- 1978 in Somalia

- Ethiopian Civil War

- Proxy wars

- Wars involving Ethiopia

- Wars involving Somalia

- Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- Wars involving Cuba

- Wars involving the Soviet Union

- Wars involving Yemen

- Rebellions in Africa

- Cuba–Soviet Union relations

- Ethiopia–Somalia military relations

- Ethiopia–Soviet Union relations

![Il-28, 3 units[88]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/Egyptian_Il-28_Beagle.JPEG/200px-Egyptian_Il-28_Beagle.JPEG)

![MiG-21, 30 units[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/MiG-21PFM-Egypt-1982.jpg/200px-MiG-21PFM-Egypt-1982.jpg)

![MiG-17, 10 units[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/MiG-17_Takes_to_the_Sky_%28cropped%29.jpg/200px-MiG-17_Takes_to_the_Sky_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![F-86 Sabre, 14 units[98]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/39/F86F_Sabres_-_Chino_Airshow_2014_%28cropped%29.jpg/194px-F86F_Sabres_-_Chino_Airshow_2014_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![F-5A/B, 15 units[98][87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/IIAF_F-5A_3-417.jpg/200px-IIAF_F-5A_3-417.jpg)

![F-5E Tiger IIs, 8 units[98][87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/IRIAF_Northrop_F-5E_Tiger_II_Talebzadeh.jpg/200px-IRIAF_Northrop_F-5E_Tiger_II_Talebzadeh.jpg)

![Canberra B.Mk.2 bombers, 2 units[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Canberra_T_4_MOD_45144929_%28cropped%29.jpg/200px-Canberra_T_4_MOD_45144929_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![T-28 Trojan, 8 units[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/T-28B_VT-2_over_NAS_Whiting_Field_c1973.jpeg/195px-T-28B_VT-2_over_NAS_Whiting_Field_c1973.jpeg)

![Saab 17, 8 units[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/SAAB_B17-20_-_Flickr_-_Ragnhild_%26_Neil_Crawford.jpg/200px-SAAB_B17-20_-_Flickr_-_Ragnhild_%26_Neil_Crawford.jpg)

![T-33A, 8 units[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/T_33_Shooting_Star-IIAF.jpg/200px-T_33_Shooting_Star-IIAF.jpg)

![C-47, 12 units[98]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Douglas_c47-a_skytrain_n1944a_cotswoldairshow_2010_arp.jpg/192px-Douglas_c47-a_skytrain_n1944a_cotswoldairshow_2010_arp.jpg)

![Aérospatiale SA.316 Alouette, 3 units[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ea/Sud_SA_316B_Alouette_III_A-247_%28cropped%29.jpg/200px-Sud_SA_316B_Alouette_III_A-247_%28cropped%29.jpg)