Mardin Province

Mardin Province

Mardin ili | |

|---|---|

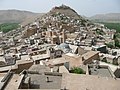

Midyat in Mardin province | |

Location of Mardin Province in Turkey | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Southeast Anatolia |

| Subregion | Mardin |

| Government | |

| • Electoral district | Mardin |

| • Governor | Mahmut Demirtaş |

| • Metropolitan Mayor | Ahmet Turk (HDP) |

| Area | |

• Total | 8,891 km2 (3,433 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

• Total | 854,716 |

| • Density | 96/km2 (250/sq mi) |

| Area code | 0482 |

| Vehicle registration | 47 |

Mardin Province (Template:Lang-tr; Template:Lang-ku;[2] Template:Lang-ar[3]) is a province of Turkey with a population of 809,719 in 2017, slightly down from the population of 835,173 in 2000. Kurds form the majority of the population,[4] followed closely by Arabs who represent 40% of the province's population.[5]

Demographics

Mardin Province is considered part of Turkish Kurdistan[6] and is populated by Kurds and Arabs who adhere to Shafi'i Islam.[7] There is also a small Assyrian Christian population left.[8] A recent study from 2013 has shown that 40% of Mardin Province's population identify as Arabs, and this proportion increases to 49% in the cities of Mardin and Midyat, where Arabs form the plurality.[5] A 1996 study estimated that the population of Mardin Province as a whole was about 75% Kurdish in 1990.[9]

Social relations

Social relations between Arabs and Kurds have historically been difficult with hostility, prejudice and stereotypes but have in recent years improved.[10] Arabs with Assyrians did not take part in the Kurdish–Turkish conflict and the position of the two groups have been described as being 'submissive' to the Turkish state, creating distrust between them and the Kurds. Kurds perceived Arabs as spies for the state and local Arabs in Mardin city tended to exclude and dominate local politics in the city.[11] Arabs started losing their grip on Mardin city in the 2010s and the Kurdish BDP won the city in the local elections in 2014. Mardin city had previously been governed by pro-state parties supported by local Arabs.[12]

Despite the difficult relations, Arab families have since the 1980s joined the Kurdish cause,[10] and Arab and Assyrian politicians from Mardin are found in Peoples' Democratic Party including Mithat Sancar and Februniye Akyol.

Language

In the first Turkish census in 1927, Kurdish and Arabic were the first language for 60.9% and 28.7% of the population, respectively. Turkish stood as the third largest language at 6.6%. In the 1935 census, Kurdish and Arabic remained the two most spoken languages for 63.8% and 24.9% of the population, respectively. Turkish remained as the third largest language at 6.9%.[13] In the 1945 census, Kurdish stood at 66.4%, Arabic at 24.1% and Turkish at 5.6%.[14] In 1950, the numbers were 66.3%, 23.1% and 7.5% for Kurdish, Arabic and Turkish, respectively.[15] The same numbers were 65.8%, 16.5% and 12.9% in 1955, and 66.4%, 20.9% and 8.6% in 1960.[16] In the last Turkish census in 1965, Kurdish remained the largest language spoken by 71% of the population, while Arabic remained the second largest language at 20% and Turkish stood at 8.9%.[17]

Religion

In the Ottoman yearbook of 1894–1895, Mardin Sanjak had a population of 34,361 and 75.8% adhered to Islam. The largest religious minority was Syriac Orthodox Assyrians who comprised 9.9% of the population, followed by Catholic Armenians at 8.3%, Catholic Assyrians at 3.4%, Protestants at 1.6% and Chaldeans at 0.9%.[18] Muslims comprised 90.5% of the population in 1927, while Christians of various denominations stood at 3.1% and Jews at 0.3%.[19] In 1935, Muslims comprised 91.2% of the population, while Christians remained the second largest minority at 5.3%. The Jewish population declined to 72 individuals from 490 in 1927.[20] In 1945, 92.1% of the population was Muslim, while Christians were 3.8% of the population.[21] The same numbers were 93.2% and 6.8% in 1955.[22] In 1960, Muslims constituted 93.7% and Christians remained at 6.3%.[23] Same numbers were 91.9% and 5.7% in 1965.[24]

It was estimated that 25,000 Assyrian members of the Syriac Orthodox Church still lived in the province in 1979.[25] Only 4,000 Assyrians remained in the province in 2020, most having migrated to Europe or Istanbul since the 1980s.[8]

Economy

In Mardin agriculture is an important branch accounting for 70% of the provinces income.[26] Bulgur, lentils or wheat and other grains are produced.[26] In the capital, there are many civil servants, mostly Turks.[26] Close markets for foreign trade are Syria and Iraq.[26]

History

Mardin comes from the Syriac word (ܡܪܕܐ) and means "fortresses".[27][28]

The first known civilization were the Subarian-Hurrians who were then succeeded in 3000 BCE by the Hurrians. The Elamites gained control around 2230 BCE and were followed by the Babylonians, Hittites, Assyrians, Romans and Byzantines.[29]

The local Assyrians/Syriacs, while reduced due to the Assyrian genocide and conflicts between the Kurds and Turks, hold on to two of the oldest monasteries in the world, Dayro d-Mor Hananyo (Turkish Deyrülzafaran, English Saffron Monastery) and Deyrulumur Monastery. The Christian community is concentrated on the Tur Abdin plateau and in the town of Midyat, with a smaller community (approximately 200) in the provincial capital. After the foundation of Turkey, the province has been a target of a Turkification policy, removing most traces of a non-turkish heritage.[30]

Inspectorate General

In 1927 the office of the Inspector general was created, which governed with martial law.[31] The province was included in the First Inspectorate-General (Template:Lang-tr) over which the Inspector General ruled. The Inspectorate-General span over the provinces of Hakkâri, Siirt, Van, Mardin, Bitlis, Sanlıurfa, Elaziğ and Diyarbakır.[32] The Inspectorate General were dissolved in 1952 during the Government of the Democrat Party.[33] The Mardin province was also included in a wider military zone in 1928, in which the entrance to the zone was forbidden for foreigners until 1965.[34]

State of Emergency

In 1987 the province was included in the OHAL region governed in a state of emergency.[35] In November 1996 the state of emergency regulation was removed.[36]

Districts

Mardin province is divided into 10 districts (capital district in bold):

- Mardin (Central district, renamed Artuklu in 2014)

- Dargeçit

- Derik

- Kızıltepe

- Mazıdağı

- Midyat

- Nusaybin

- Ömerli

- Savur

- Yeşilli

Gallery

- Islamic monuments in Mardin Province

-

Minaret of the Grand Mosque of Mardin (12th century) and the view of the Mesopotamian plains.

-

Kasimiye Madrasa (14th century)

-

Zinciriye Madrasa (14th century)

-

View of Savur and the grand mosque in the center

-

Abdullatif Mosque (14th century)

- Christian monuments in Mardin Province

-

Dayro d-Mor Hananyo monastery

-

Syriac Orthodox Church in Midyat

Bibliography

- Dündar, Fuat (2000), Türkiye nüfus sayımlarında azınlıklar (in Turkish), ISBN 9789758086771

Metropolitan Municipality Mayors Government of Mardin

- 2009-2014 Mehmet Vecdi Karaman AK Party

- 2014-2015 Ahmet Türk BDP

- 2015-current Ahmet Türk HDP

References

- ^ "Population of provinces by years - 2000-2018". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "Karsazekî Kurd ê ji Mêrdînê bi koronayê jiyana xwe ji dest da" (in Kurdish). Rûdaw. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ المستدرك على تتمة الأعلام. "المستدرك على تتمة الأعلام" (in Arabic). p. 138.

- ^ Watts, Nicole F. (2010). Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-295-99050-7.

- ^ a b Ayse Guc Isik, 2013.The Intercultural Engagement in Mardin. Australian Catholic University. pp. 46–48.

- ^ "Kurds, Kurdistān". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2 ed.). BRILL. 2002. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ Tosun, Mehtap (2018). "Dissolution of Craft in the Context of Ethnicity, Gender and Class" (PDF). Middle East Technical University: 120.

- ^ a b "Turkish Assyrians worry about declining community, fragile heritage". The Arab Weekly. 6 June 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Mutlu, Servet (1996). "Ethnic Kurds in Turkey: A Demographic Study". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 28 (4): 517–541. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063819. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 176151. S2CID 154212694. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ a b Costa, Elisabetta (2016). Social Media in Southeast Turkey: Love, Kinship and Politics. UCL Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9781910634530.

- ^ Biner, Zerrin Ozlem (2019). States of Dispossession: Violence and Precarious Coexistence in Southeast Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. xiv–xv. ISBN 9780812296594.

- ^ Costa, Elisabetta (2016). Social Media in Southeast Turkey: Love, Kinship and Politics. UCL Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9781910634530.

- ^ Dündar (2000), pp. 157 & 164.

- ^ Dündar (2000), pp. 179–180.

- ^ Dündar (2000), p. 188.

- ^ Dündar (2000), pp. 200–201, 209–210.

- ^ Dündar (2000), p. 220.

- ^ Tosun, Mehtap (2018). "Dissolution of Craft in the Context of Ethnicity, Gender and Class" (PDF). Middle East Technical University: 118.

- ^ Dündar (2010), p. 159.

- ^ Dündar (2010), p. 178.

- ^ Dündar (2000), p. 175.

- ^ Dündar (2000), p. 203.

- ^ Dündar (2000), p. 212.

- ^ Dündar (2000), p. 223.

- ^ Christian Minorities of Turkey: Report Produced by the Churches Committee on Migrant Workers in Europe. 1979. p. 12. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Costa, Elisabetta (2016). "Social Media in Southeast Turkey". www.jstor.org. p. 18. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Lipiński, Edward (2000). The Aramaeans: Their Ancient History, Culture, Religion. Peeters Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 978-90-429-0859-8.

- ^ Payne Smith's A Compendious Syriac Dictionary, Dukhrana.com

- ^ "- Antik Tatlıdede Konağı – Mardin". www.tatlidede.com.tr. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Üngör, Uğur (2011), The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 245. ISBN 0-19-960360-X.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost (1 January 2007). The Settlement Issue in Turkey and the Kurds: An Analysis of Spatical Policies, Modernity and War. BRILL. p. 53. ISBN 978-90-04-15557-2.

- ^ Bayir, Derya (22 April 2016). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-317-09579-8.

- ^ Fleet, Kate; Kunt, I. Metin; Kasaba, Reşat; Faroqhi, Suraiya (17 April 2008). The Cambridge History of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost (28 May 2007). The Settlement Issue in Turkey and the Kurds: An Analysis of Spatial Policies, Modernity and War. BRILL. p. 303. ISBN 978-90-474-2011-8.

- ^ Biner, Zerrin Ozlem (8 November 2019). States of Dispossession: Violence and Precarious Coexistence in Southeast Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9659-4.

- ^ "Turkey, Country Assessment, November 2002" (PDF). Ecoi. Retrieved 8 April 2020.