Prucalopride

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Resolor, Resotran, Motegrity |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a619011 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H26ClN3O3 |

| Molar mass | 367.87 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

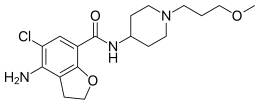

Prucalopride, brand names Resolor and Motegrity among others, is a drug acting as a selective, high affinity 5-HT4 receptor agonist[1] which targets the impaired motility associated with chronic constipation, thus normalizing bowel movements.[2][3][4][5][6][7] Prucalopride was approved for medical use in the European Union in 2009,[8] in Canada in 2011,[9] in Israel in 2014,[10] and in the United States in December 2018.[11] The drug has also been tested for the treatment of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction.[12][13]

Medical uses

The primary measure of efficacy in the clinical trials is three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week; a secondary measure is an increase of at least one complete spontaneous bowel movement per week.[7][14][15] Further measures are improvements in PAC-QOL[16] (a quality of life measure) and PAC-SYM[17] (a range of stool, abdominal, and rectal symptoms associated with chronic constipation). Infrequent bowel movements, bloating, straining, abdominal pain, and defecation urge with inability to evacuate can be severe symptoms, significantly affecting quality of life.[18][19][20][21][22]

In three large clinical trials, 12 weeks of treatment with prucalopride 2 and 4 mg/day resulted in a significantly higher proportion of patients reaching the primary efficacy endpoint of an average of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements than with placebo.[7][14][15] There was also significantly improved bowel habit and associated symptoms, patient satisfaction with bowel habit and treatment, and HR-QOL in patients with severe chronic constipation, including those who did not experience adequate relief with prior therapies (>80% of the trial participants).[7][14][15] The improvement in patient satisfaction with bowel habit and treatment was maintained during treatment for up to 24 months; prucalopride therapy was generally well tolerated.[23][24]

Small clinical trials suggested that prucalopride administration results in the 5-HT4 receptor agonism-associated memory enhancing in healthy participants improving their ability to recall and increasing neural activation in the hippocampus and functionally related areas.[25][26]

Contraindications

Prucalopride is contraindicated where there is hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients, renal impairment requiring dialysis, intestinal perforation or obstruction due to structural or functional disorder of the gut wall, obstructive ileus, severe inflammatory conditions of the intestinal tract, such as Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis and toxic megacolon/megarectum.[27]

Side effects

Prucalopride has been given orally to ~2700 patients with chronic constipation in controlled clinical trials. The most frequently reported side effects are headache and gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea or diarrhea). Such reactions occur predominantly at the start of therapy and usually disappear within a few days with continued treatment.[27]

Mechanism of action

Prucalopride, a first in class dihydro-benzofuran-carboxamide, is a selective, high affinity serotonin (5-HT4) receptor agonist with enterokinetic activities.[27] Prucalopride alters colonic motility patterns via serotonin 5-HT4 receptor stimulation: it stimulates colonic mass movements, which provide the main propulsive force for defecation.

The observed effects are exerted via highly selective action on 5-HT4 receptors:[27] prucalopride has >150-fold higher affinity for 5-HT4 receptors than for other receptors.[1][28] Prucalopride differs from other 5-HT4 agonists such as tegaserod and cisapride, which at therapeutic concentrations also interact with other receptors (5-HT1B/D and the cardiac human ether-a-go-go K+ or hERG channel respectively) and this may account for the adverse cardiovascular events that have resulted in the restricted availability of these drugs.[28] Clinical trials evaluating the effect of prucalopride on QT interval and related adverse events have not demonstrated significant differences compared with placebo.[27]

Pharmacokinetics

Prucalopride is rapidly absorbed (Cmax attained 2–3 hours after single 2 mg oral dose) and is extensively distributed. Metabolism is not the major route of elimination. In vitro, human liver metabolism is very slow and only minor amounts of metabolites are found. A large fraction of the active substance is excreted unchanged (about 60% of the administered dose in urine and at least 6% in feces). Renal excretion of unchanged prucalopride involves both passive filtration and active secretion. Plasma clearance averages 317 ml/min, terminal half-life is 24–30 hours,[29] and steady-state is reached within 3–4 days. On once daily treatment with 2 mg prucalopride, steady-state plasma concentrations fluctuate between trough and peak values of 2.5 and 7 ng/ml, respectively.[27]

In vitro data indicate that prucalopride has a low interaction potential, and therapeutic concentrations of prucalopride are not expected to affect the CYP-mediated metabolism of co-medicated medicinal products.[27]

Approval

In the European Economic Area, prucalopride was originally approved for the symptomatic treatment of chronic constipation in women in whom laxatives fail to provide adequate relief.[27] Subsequently, it has been approved by the European Commission for use in adults – that is, including male patients – for the same indication.[30]

References

- ^ a b Briejer MR, Bosmans JP, Van Daele P, Jurzak M, Heylen L, Leysen JE, et al. (June 2001). "The in vitro pharmacological profile of prucalopride, a novel enterokinetic compound". European Journal of Pharmacology. 423 (1): 71–83. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01087-1. PMID 11438309.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT00793247 for "Efficacy Study of Prucalopride to Treat Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction (CIP)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Emmanuel AV, Kamm MA, Roy AJ, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L (January 2012). "Randomised clinical trial: the efficacy of prucalopride in patients with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction--a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over, multiple n = 1 study". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 35 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04907.x. PMC 3298655. PMID 22061077.

- ^ Smart CJ, Ramesh AN (August 2012). "The successful treatment of acute refractory pseudo-obstruction with prucalopride". Colorectal Disease. 14 (8): e508. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02929.x. PMID 22212130. S2CID 29060148.

- ^ Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, McKinzie S (May 1999). "Selective stimulation of colonic transit by the benzofuran 5HT4 agonist, prucalopride, in healthy humans". Gut. 44 (5): 682–6. doi:10.1136/gut.44.5.682. PMC 1727485. PMID 10205205.

- ^ Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Thomforde G, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR (February 2001). "Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorder". Gastroenterology. 120 (2): 354–60. doi:10.1053/gast.2001.21166. PMID 11159875.

- ^ a b c d Tack J, van Outryve M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L (March 2009). "Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives". Gut. 58 (3): 357–65. doi:10.1136/gut.2008.162404. PMID 18987031. S2CID 206948212.

- ^ "Resolor EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived from the original on 2010-01-31.

- ^ "Health Canada, Notice of Decision for Resotran". hc-sc.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Digestive Remedies in Israel". www.euromonitor.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Motegrity (prucalopride)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 December 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Briejer MR, Prins NH, Schuurkes JA (October 2001). "Effects of the enterokinetic prucalopride (R093877) on colonic motility in fasted dogs". Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 13 (5): 465–72. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00280.x. PMID 11696108. S2CID 13610558.

- ^ Oustamanolakis P, Tack J (February 2012). "Prucalopride for chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 35 (3): 398–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04947.x. PMID 22221087. S2CID 5526239.

- ^ a b c Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L (May 2008). "A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (22): 2344–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0800670. PMID 18509121.

- ^ a b c Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, Ausma J (February 2009). "Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation--a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 29 (3): 315–28. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03884.x. PMID 19035970. S2CID 40122406.

- ^ Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, McDermott A, Chassany O (May 2005). "Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 40 (5): 540–51. doi:10.1080/00365520510012208. PMID 16036506. S2CID 34620643.

- ^ Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, Taylor L, Miner P (September 1999). "Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 34 (9): 870–7. doi:10.1080/003655299750025327. PMID 10522604.

- ^ Johanson JF, Kralstein J (March 2007). "Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 25 (5): 599–608. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. PMID 17305761. S2CID 25400560.

- ^ Koch A, Voderholzer WA, Klauser AG, Müller-Lissner S (August 1997). "Symptoms in chronic constipation". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 40 (8): 902–6. doi:10.1007/BF02051196. PMID 9269805. S2CID 28066729.

- ^ McCrea GL, Miaskowski C, Stotts NA, Macera L, Paul SM, Varma MG (April 2009). "Gender differences in self-reported constipation characteristics, symptoms, and bowel and dietary habits among patients attending a specialty clinic for constipation". Gender Medicine. 6 (1): 259–71. doi:10.1016/j.genm.2009.04.007. PMID 19467522.

- ^ Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L (November 2001). "An epidemiological survey of constipation in canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 96 (11): 3130–7. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05259.x. PMID 11721760. S2CID 8578282.

- ^ Wald A, Scarpignato C, Kamm MA, Mueller-Lissner S, Helfrich I, Schuijt C, et al. (July 2007). "The burden of constipation on quality of life: results of a multinational survey". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 26 (2): 227–36. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03376.x. PMID 17593068. S2CID 19457828.

- ^ Camilleri M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L (2009). "Long-term follow-up of safety and satisfaction with bowel function in response to oral prucalopride in patients with chronic constipation [Abstract]". Gastroenterology. 136 (Suppl 1): 160. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(09)60143-8.

- ^ Van Outryve MJ, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L (2008). "Long-term follow-up study of oral prucalopride (Resolor) administered to patients with chronic constipation [Abstract T1400]". Gastroenterology. 134 (4 (suppl 1)): A547. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(08)62554-8.

- ^ Murphy, S. E.; Wright, L. C.; Browning, M.; Cowen, P. J.; Harmer, C. J. (2020). "A role for 5-HT4 receptors in human learning and memory". Psychological Medicine. 50 (16): 2722–2730. doi:10.1017/S0033291719002836. ISSN 0033-2917. PMID 31615585. S2CID 204350650.

- ^ de Cates, A. N.; Wright, L. C.; Martens, M. A. G.; Gibson, D.; Türkmen, C.; Filippini, N.; Cowen, P. J.; Harmer, C. J.; Murphy, S. E. (2021). "Déjà-vu? Neural and behavioural effects of the 5-HT4 receptor agonist, prucalopride, in a hippocampal-dependent memory task". Translational Psychiatry. 11 (1): 497. doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01568-4. ISSN 2158-3188. PMC 8488034. PMID 34602607.

- ^ a b c d e f g h SmPC. Summary of product characteristics Resolor (prucalopride) October, 2009: 1-9.

- ^ a b De Maeyer JH, Lefebvre RA, Schuurkes JA (February 2008). "5-HT4 receptor agonists: similar but not the same". Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 20 (2): 99–112. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01059.x. PMID 18199093. S2CID 43095011.

- ^ Frampton JE (2009). "Prucalopride". Drugs. 69 (17): 2463–76. doi:10.2165/11204000-000000000-00000. PMID 19911858.

- ^ "Shire Receives European Approval to Use Resolor® (prucalopride) in Men for the Symptomatic Treatment of Chronic Constipation". www.shire.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

External links

- "Prucalopride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Prucalopride succinate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.