Potato

| Potato | |

|---|---|

| |

| Potato cultivars appear in a variety of colors, shapes, and sizes. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Solanum |

| Species: | S. tuberosum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Solanum tuberosum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

see list | |

The potato (/pəˈteɪtoʊ/) is a starchy root vegetable native to the Americas that is consumed as a staple food in many parts of the world. Potatoes are tubers of the plant Solanum tuberosum, a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern United States to southern Chile. Genetic studies show that the potato has a single origin, in the area of present-day southern Peru and extreme northwestern Bolivia. Potatoes were domesticated there about 7,000–10,000 years ago from a species in the S. brevicaule complex. Many varieties of the potato are cultivated in the Andes region of South America, where the species is indigenous.

The Spanish introduced potatoes to Europe in the second half of the 16th century from the Americas. They are a staple food in many parts of the world and an integral part of much of the world's food supply. Following millennia of selective breeding, there are now over 5,000 different varieties of potatoes. The importance of the potato as a food source and culinary ingredient varies by region and is still changing. It remains an essential crop in Europe, especially Northern and Eastern Europe, where per capita production is still the highest in the world, while the most rapid expansion in production during the 21st century was in southern and eastern Asia, with China and India leading the world production of 376 million tonnes (370,000,000 long tons; 414,000,000 short tons) as of 2021.

Like the tomato, the potato is a nightshade in the genus Solanum, and the aerial parts of the potato contain the toxin solanine. Normal potato tubers that have been grown and stored properly produce glycoalkaloids in negligible amounts, but, if sprouts and potato skins are exposed to light, tubers can become toxic.

Etymology

The English word "potato" comes from Spanish patata. The Royal Spanish Academy says the Spanish word is a hybrid of the Taíno batata (sweet potato) and the Quechua papa (potato).[2][3] The name originally referred to the sweet potato although the two plants are not biologically closely related, despite their similar appearance. The 16th-century English herbalist John Gerard referred to sweet potatoes as "common potatoes", and used the terms "bastard potatoes" and "Virginia potatoes" for the species now known as potato.[4] In many of the chronicles detailing agriculture and plants no distinction is made between the two.[5] Potatoes are occasionally referred to as "Irish potatoes" or "white potatoes" in the United States to distinguish them from sweet potatoes.[4]

The name "spud" for a potato comes from the digging of soil (or a hole) prior to the planting of potatoes. The word has an unknown origin and was originally (c. 1440) used as a term for a short knife or dagger, probably related to the Latin spad-, a word root meaning "sword"; compare Spanish espada, English "spade", and "spadroon". It subsequently transferred over to a variety of digging tools. Around 1845, the name transferred to the tuber itself, the first record of this usage being in New Zealand English.[6]

At least six languages—Afrikaans, Dutch, French, (West) Frisian, Hebrew, Persian[7] and some variants of German—use a term for "potato" that means "earth apple" or "ground apple".[8][9]

Description

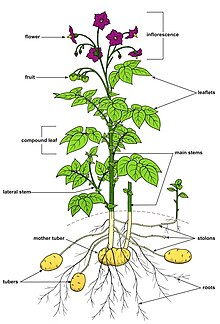

Potato plants are herbaceous perennials that grow about 60 centimetres (24 inches) high, depending on variety, with the leaves dying back after flowering, fruiting and tuber formation. The alternately arranged leaves have a petiole with six to eight symmetrical leaflets and one top, unpaired leaflet, which is 10 cm (3.9 in) to 30 cm (12 in) long and 5 cm (2.0 in) to 15 cm (5.9 in) wide. They present hairs or trichomes on their surface, to varying degrees depending on the cultivar.[citation needed]

Potato plants bear white, pink, red, blue, or purple flowers with yellow stamens. Potatoes are mostly cross-pollinated by insects such as bumblebees, which carry pollen from other potato plants, though a substantial amount of self-fertilizing occurs as well.[citation needed]

The plant develops tubers as a nutrient storage organ. Traditionally, it was thought that the tubers are roots because they are developed underground. In fact, they are stems that form from thickened rhizomes) at the tips of stolons. These stolons arise as branches from underground nodes.[10] On the surface of the tubers there are "eyes," which act as sinks to protect the vegetative buds from which the stems originate. The "eyes" are arranged in helical form. In addition, the tubers have small holes that allow breathing, called lenticels. The lenticels are circular and their number varies depending of the size of the tuber and environmental conditions. Tubers form in response to decreasing day length, although this tendency has been minimized in commercial varieties.[11]

After flowering, potato plants produce small green fruits that resemble green cherry tomatoes, each containing about 300 very small seeds.[12] Like all parts of the plant except the tubers, the fruit contain the toxic alkaloid solanine and are therefore unsuitable for consumption. All new potato varieties are grown from seeds, also called "true potato seed", "TPS" or "botanical seed" to distinguish it from seed tubers.[13] New varieties grown from seed can be propagated vegetatively by planting tubers, pieces of tubers cut to include at least one or two eyes, or cuttings, a practice used in greenhouses for the production of healthy seed tubers. Plants propagated from tubers are clones of the parent, whereas those propagated from seed produce a range of different varieties.[citation needed]

History

Wild potato species occur from the southern United States to southern Chile.[14] The potato was first domesticated in the region of modern-day southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia[15] by pre-Columbian farmers, around Lake Titicaca.[16] Potatoes were domesticated there about 7,000–10,000 years ago from a species in the S. brevicaule complex.[15][16][17] Over 99% of potatoes presently cultivated worldwide descend from varieties that originated in the lowlands of south-central Chile. The potato was brought to Europe by the Spanish during the Columbian exchange after 1492.[18]

The earliest archaeologically verified potato tuber remains have been found at the coastal site of Ancon (central Peru), dating to 2500 BC.[19][20] The most widely cultivated variety, Solanum tuberosum tuberosum, is indigenous to the Chiloé Archipelago, and has been cultivated by the local indigenous people since before the Spanish conquest.[21][22]

Following the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, the Spanish introduced the potato to Europe in the second half of the 16th century, part of the Columbian exchange. The staple was subsequently conveyed by European mariners (possibly including Russian-American Company) to territories and ports throughout the world, especially their colonies.[23] The potato was slow to be adopted by European and colonial farmers, but after 1750 it became an important food staple and field crop[23] and played a major role in the European 19th century population boom.[17] According to conservative estimates, the introduction of the potato was responsible for a quarter of the growth in Old World population and urbanization between 1700 and 1900.[24] However, lack of genetic diversity, due to the very limited number of varieties initially introduced, left the crop vulnerable to disease. In 1845, a plant disease known as late blight, caused by the fungus-like oomycete Phytophthora infestans, spread rapidly through the poorer communities of western Ireland as well as parts of the Scottish Highlands, resulting in the crop failures that led to the Great Irish Famine.[25][23]

The major species grown worldwide is S. tuberosum (a tetraploid with 48 chromosomes), and modern varieties of this species are the most widely cultivated. There are also four diploid species (with 24 chromosomes): S. stenotomum, S. phureja, S. goniocalyx, and S. ajanhuiri. There are two triploid species (with 36 chromosomes): S. chaucha and S. juzepczukii. There is one pentaploid cultivated species (with 60 chromosomes): S. curtilobum. There are two major subspecies of S. tuberosum: andigena, or Andean; and tuberosum, or Chilean.[26] The Andean potato is adapted to the short-day conditions prevalent in the mountainous equatorial and tropical regions where it originated; the Chilean potato, however, native to the Chiloé Archipelago, is adapted to the long-day conditions prevalent in the higher latitude region of southern Chile.[21]

The International Potato Center, based in Lima, Peru, holds 4,870 types of potato germplasm, most of which are traditional landrace cultivars.[27] The international Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium announced in 2009 that they had achieved a draft sequence of the potato genome, containing 12 chromosomes and 860 million base pairs, making it a medium-sized plant genome.[28] More than 99% of all current varieties of potatoes currently grown are direct descendants of a subspecies that once grew in the lowlands of south-central Chile.[29] Nonetheless, genetic testing of the wide variety of cultivars and wild species affirms that all potato subspecies derive from a single origin in the area of present-day southern Peru and extreme Northwestern Bolivia (from a species in the S. brevicaule complex).[15][16][17]

Most modern potatoes grown in North America arrived through European settlement and not independently from the South American sources, although at least one wild potato species, S. fendleri, occurs in North America, where it is used in breeding for resistance to a nematode species that attacks cultivated potatoes. A secondary center of genetic variability of the potato is Mexico, where important wild species that have been used extensively in modern breeding are found, such as the hexaploid S. demissum, as a source of resistance to the devastating late blight disease (Phytophthora infestans).[25] Another relative native to this region, Solanum bulbocastanum, has been used to genetically engineer the potato to resist potato blight.[30] Many such wild relatives are useful for breeding resistance to P. infestans.[31]

Little of the diversity found in Solanum ancestral and wild relative is found outside of the original South American range.[32] This makes these South American species highly valuable in breeding.[32]

Breeding

Potatoes, both S. tuberosum and most of its wild relatives, are self-incompatible: they bear no useful fruit when self-pollinated. This trait is problematic for crop breeding, as all sexually-produced plants must be hybrids. The gene responsible for its trait as well as mutations to disable it are now known. Self-compatibility has successfully been introduced both to diploid potatoes (including a special line of S. tuberosum) by CRISPR-Cas9.[13] Plants having a 'Sli' gene produce pollen which is compatible to its own parent and plants with similar S genes.[33] This gene was cloned by Wageningen University and Solynta in 2021, which would allow for faster and more focused breeding.[13][34]

Diploid hybrid potato breeding is a recent area of potato genetics supported by the finding that simultaneous homozygosity and fixation of donor alleles is possible.[35] Wild potato species useful for breeding may include Solanum desmissum and S. stoloniferum, among others.[36]

Sucrose is a product of photosynthesis.[37] Ferreira et al. (2010) found that the genes for starch biosynthesis start to be transcribed at the same time as sucrose synthase activity begins.[37] This transcription – including starch synthase – also shows a diurnal rhythm, correlating with the sucrose supply arriving from the leaves.[37]

Varieties

There are some 5,000 potato varieties worldwide, 3,000 of them in the Andes alone — mainly in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia. Over 100 cultivars might be found in a single valley, and a dozen or more might be maintained by a single agricultural household.[38] Around 80 varieties are commercially available in the UK.[39]

For culinary purposes, varieties are often differentiated by their waxiness: floury or mealy baking potatoes have more starch (20–22%) than waxy boiling potatoes (16–18%). The distinction may also arise from variation in the comparative ratio of two different potato starch compounds: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose, a long-chain molecule, diffuses from the starch granule when cooked in water, and lends itself to dishes where the potato is mashed. Varieties that contain a slightly higher amylopectin content, which is a highly branched molecule, help the potato retain its shape after being boiled in water.[40] Potatoes that are good for making potato chips or potato crisps are sometimes called "chipping potatoes", which means they meet the basic requirements of similar varietal characteristics, being firm, fairly clean, and fairly well-shaped.[41]

Immature potatoes may be sold fresh from the field as "creamer" or "new" potatoes and are particularly valued for their taste. They are typically small in size and tender, with a loose skin, and flesh containing a lower level of starch than other potatoes. In the United States they are generally either a Yukon Gold potato or a red potato, called gold creamers or red creamers respectively.[42][43] In the UK, the Jersey Royal is a famous type of new potato.[44]

The European Cultivated Potato Database is an online collaborative database of potato variety descriptions updated and maintained by the Scottish Agricultural Science Agency within the framework of the European Cooperative Programme for Crop Genetic Resources Networks—which is run by the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute.[45]

Dozens of potato cultivars have been selectively bred specifically for their skin or flesh color, including gold, red, and blue varieties.[46] These contain varying amounts of phytochemicals, including carotenoids for gold/yellow or polyphenols for red or blue cultivars.[47] Carotenoid compounds include provitamin A alpha-carotene and beta-carotene, which are converted to the essential nutrient, vitamin A, during digestion. Anthocyanins mainly responsible for red or blue pigmentation in potato cultivars do not have nutritional significance, but are used for visual variety and consumer appeal.[48] In 2010, potatoes were bioengineered specifically for these pigmentation traits.[49]

Genetic engineering

Genetic research has produced several genetically modified varieties. 'New Leaf', owned by Monsanto Company, incorporates genes from Bacillus thuringiensis (source of most Bt toxins in transcrop use), which confers resistance to the Colorado potato beetle; 'New Leaf Plus' and 'New Leaf Y', approved by US regulatory agencies during the 1990s, also include resistance to viruses. McDonald's, Burger King, Frito-Lay, and Procter & Gamble announced they would not use genetically modified potatoes, and Monsanto published its intent to discontinue the line in March 2001.[50]

Potato starch contains two types of glucan, amylose and amylopectin, the latter of which is most industrially useful. Waxy potato varieties produce waxy potato starch, which is almost entirely amylopectin, with little or no amylose. BASF developed the 'Amflora' potato, which was modified to express antisense RNA to inactivate the gene for granule bound starch synthase, an enzyme which catalyzes the formation of amylose.[51] 'Amflora' potatoes therefore produce starch consisting almost entirely of amylopectin, and are thus more useful for the starch industry. In 2010, the European Commission cleared the way for 'Amflora' to be grown in the European Union for industrial purposes only—not for food. Nevertheless, under EU rules, individual countries have the right to decide whether they will allow this potato to be grown on their territory. Commercial planting of 'Amflora' was expected in the Czech Republic and Germany in the spring of 2010, and Sweden and the Netherlands in subsequent years.[52]

Another GM potato variety developed by BASF is 'Fortuna' which was made resistant to late blight by adding two resistance genes, blb1 and blb2, which originate from the Mexican wild potato S. bulbocastanum.[53][54] Rpi-blb1 is a nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NB-LRR/NLR), an R-gene-produced immunoreceptor.[55] It has been introgressed from wild relatives (various Solanum spp.) into the common potato.[55] Rpi-blb1 resists Late Blight (P. infestans).[55]

In October 2011 BASF requested cultivation and marketing approval as a feed and food from the EFSA. In 2012, GMO development in Europe was stopped by BASF.[56][57] In November 2014, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) approved a genetically modified potato developed by Simplot, which contains genetic modifications that prevent bruising and produce less acrylamide when fried than conventional potatoes; the modifications do not cause new proteins to be made, but rather prevent proteins from being made via RNA interference.[58]

Genetically modified varieties have met public resistance in the U.S. and in the European Union.[59][60]

Cultivation

Seed potatoes

Potatoes are generally grown from "seed potatoes", tubers specifically grown to be free from disease and to provide consistent and healthy plants. To be disease free, the areas where seed potatoes are grown are selected with care. In the US, this restricts production of seed potatoes to only 15 states out of all 50 states where potatoes are grown.[61] These locations are selected for their cold, hard winters that kill pests and summers with long sunshine hours for optimum growth. In the UK, most seed potatoes originate in Scotland, in areas where westerly winds reduce aphid attack and the spread of potato virus pathogens.[62]

Specially genetically modified potatoes can also be grown from true seeds.[13] This is rarely used in breeding experimentation.[13]

Phases of growth

Potato growth can be divided into five phases. During the first phase, sprouts emerge from the seed potatoes and root growth begins. During the second, photosynthesis begins as the plant develops leaves and branches above-ground and stolons develop from lower leaf axils on the below-ground stem. In the third phase the tips of the stolons swell forming new tubers and the shoots continue to grow and flowers typically develop soon after. Tuber bulking occurs during the fourth phase, when the plant begins investing the majority of its resources in its newly formed tubers. At this phase, several factors are critical to a good yield: optimal soil moisture and temperature, soil nutrient availability and balance, and resistance to pest attacks. The fifth phase is the maturation of the tubers: the leaves and stems senesce and the tuber skins harden.[63][64]

New tubers may start growing at the surface of the soil. Since exposure to light leads to an undesirable greening of the skins and the development of solanine as a protection from the sun's rays, growers cover surface tubers. Commercial growers cover them by piling additional soil around the base of the plant as it grows (called "hilling" up, or in British English "earthing up"). An alternative method, used by home gardeners and smaller-scale growers, involves covering the growing area with mulches such as straw or plastic sheets.[65]

Correct potato husbandry requires thorough ground preparation, involving harrowing, plowing, and rolling, and sufficient water.[66] Potatoes are sensitive to heavy frosts, which damage them in the ground or when stored.[67]

-

Planting

-

Field in Fort Fairfield, Maine

-

Immature potato plants

-

Potatoes grown in a tall bag are common in gardens as they minimize digging.

Pests and diseases

The historically significant Phytophthora infestans, the cause of late blight, remains an ongoing problem in Europe[25] and the United States.[68] Other potato diseases include Rhizoctonia, Sclerotinia, Pectobacterium carotovorum (black leg), powdery mildew, powdery scab and leafroll virus.[69][70]

Insects that commonly transmit potato diseases or damage the plants include the Colorado potato beetle, the potato tuber moth, the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae), the potato aphid, Tuta absoluta, beet leafhoppers, thrips, and mites. The Colorado potato beetle is considered the most important insect defoliator of potatoes, devastating entire crops.[71] The potato cyst nematode is a microscopic worm that feeds on the roots, thus causing the potato plants to wilt. Since its eggs can survive in the soil for several years, crop rotation is recommended.[72]

Harvest

On a small scale, potatoes can be harvested using a hoe or spade, or simply by hand. Commercial harvesting is done with large potato harvesters, which scoop up the plant and surrounding earth. This is transported up an apron chain consisting of steel links several feet wide, which separates some of the earth. The chain deposits into an area where further separation occurs. The most complex designs use vine choppers and shakers, along with a blower system to separate the potatoes from the plant. The result is then usually run past workers who continue to sort out plant material, stones, and rotten potatoes before the potatoes are continuously delivered to a wagon or truck. Further inspection and separation occurs when the potatoes are unloaded from the field vehicles and put into storage.[73]

Potatoes are usually cured after harvest to improve skin-set. Skin-set is the process by which the skin of the potato becomes resistant to skinning damage. Potato tubers may be susceptible to skinning at harvest and suffer skinning damage during harvest and handling operations. Curing allows the skin to fully set and any wounds to heal. Wound-healing prevents infection and water-loss from the tubers during storage. Curing is normally done at relatively warm temperatures (10 to 16 °C or 50 to 60 °F) with high humidity and good gas-exchange if at all possible.[74]

Storage

Storage facilities need to be carefully designed to keep the potatoes alive and slow the natural process of sprouting which involves the breakdown of starch. It is crucial that the storage area be dark, ventilated well, and, for long-term storage, maintained at temperatures near 4 °C (39 °F). For short-term storage, temperatures of about 7 to 10 °C (45 to 50 °F) are preferred.[75]

Temperatures below 4 °C (39 °F) convert the starch in potatoes into sugar, which alters their taste and cooking qualities and leads to higher acrylamide levels in the cooked product, especially in deep-fried dishes. The discovery of acrylamides in starchy foods in 2002 has caused concern, but it is not likely that the acrylamides in food, even if it is somewhat burnt, causes cancer in humans.[76]

Chemicals are used to suppress sprouting of tubers during storage. Chlorpropham is the main chemical used, but it has been banned in the EU over toxicity concerns.[77] Alternatives include ethylene, spearmint and orange oils, and 1,4-dimethylnaphthalene.[77]

Under optimum conditions in commercial warehouses, potatoes can be stored for up to 10–12 months.[75] The commercial storage and retrieval of potatoes involves several phases: first drying surface moisture; wound healing at 85% to 95% relative humidity and temperatures below 25 °C (77 °F); a staged cooling phase; a holding phase; and a reconditioning phase, during which the tubers are slowly warmed. Mechanical ventilation is used at various points during the process to prevent condensation and the accumulation of carbon dioxide.[75]

Production

| Potato production – 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) |

| 94.3 | |

| 54.2 | |

| 21.4 | |

| 18.6 | |

| 18.3 | |

| World | 376 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[78] | |

-

Production of potatoes (2019)[79]

-

Potatoes are one of the most widely produced primary crops in the world.

In 2021, world production of potatoes was 376 million tonnes (370,000,000 long tons; 414,000,000 short tons), led by China with 25% of the total. Other major producers were India and Ukraine (table).

The world dedicated 18.6 million hectares (46 million acres) to potato cultivation in 2010; the world average yield was 17.4 tonnes per hectare (7.8 short tons per acre). The United States was the most productive country, with a nationwide average yield of 44.3 tonnes per hectare (19.8 short tons per acre).[80]

New Zealand farmers have demonstrated some of the best commercial yields in the world, ranging between 60 and 80 tonnes per hectare, some reporting yields of 88 tonnes of potatoes per hectare.[81][82][83]

There is a big gap among various countries between high and low yields, even with the same variety of potato. Average potato yields in developed economies ranges between 38 and 44 metric tons per hectare (15 and 18 long ton/acre; 17 and 20 short ton/acre). China and India accounted for over a third of world's production in 2010, and had yields of 14.7 and 19.9 metric tons per hectare (5.9 and 7.9 long ton/acre; 6.6 and 8.9 short ton/acre) respectively.[80] The yield gap between farms in developing economies and developed economies represents an opportunity loss of over 400 million metric tons (440 million short tons; 390 million long tons) of potato, or an amount greater than 2010 world potato production. Potato crop yields are determined by factors such as the crop breed, seed age and quality, crop management practices and the plant environment. Improvements in one or more of these yield determinants, and a closure of the yield gap, can be a major boost to food supply and farmer incomes in the developing world.[84][85] The food energy yield of potatoes—about 95 gigajoules per hectare (9.2 million kilocalories per acre)—is higher than that of maize (78 GJ/ha or 7.5 million kcal/acre), rice (77 GJ/ha or 7.4 million kcal/acre), wheat (31 GJ/ha or 3 million kcal/acre), or soybeans (29 GJ/ha or 2.8 million kcal/acre).[86]

Impact of climate change on production

Climate change is predicted to have significant effects on global potato production.[87] Like many crops, potatoes are likely to be affected by changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide, temperature and precipitation, as well as interactions between these factors.[87] As well as affecting potatoes directly, climate change will also affect the distributions and populations of many potato diseases and pests. While potato is less important than maize, rice, wheat and soybeans, which are collectively responsible for around two-thirds of all calories consumed by humans (both directly and indirectly as animal feed),[88] it still is one of the world's most important food crops.[89] Altogether, one 2003 estimate suggests that future (2040–2069) worldwide potato yield would be 18-32% lower than it was at the time, driven by declines in hotter areas like Sub-Saharan Africa,[87] unless farmers and potato cultivars can adapt to the new environment.[90]

Potato plants and crop yields are predicted to benefit from the CO2 fertilization effect,[91] which would increase photosynthetic rates and therefore growth, reduce water consumption through lower transpiration from stomata and increase starch content in the edible tubers.[87] However, potatoes are more sensitive to soil water deficits than some other staple crops like wheat,[92] so in countries like Bolivia, where the rainy season has shortened in recent decades, the potato growing season has shortened as well.[93] This can get worse in the future: for instance, the amount of arable land suitable for rainfed potato production in the UK may decrease by at least 75%.[94] These changes are likely to lead to increased demand for irrigation water, particularly during the potato growing season.[87]

Potatoes grow best under temperate conditions.[95] Tuber growth and yield can be severely reduced by temperature fluctuations outside 5–30 °C (41–86 °F).[93] Temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) can have a range of negative effects on potato, from physiological damage such as brown spots on tubers, to slower growth, premature sprouting and lower starch content.[96] These effects can reduce crop yield and the number and weight of tubers. As a result, areas where current temperatures are near the limits of potatoes' temperature range (e.g. much of sub-Saharan Africa)[87] will likely suffer large reductions in potato crop yields in the future.[95] On the other hand, low temperatures reduce potato growth and present risk of frost damage.[87] At high altitudes and in high latitude countries such as Canada and Russia, potato growth is currently limited or impossible due to risks of frost damage, and rising temperatures will likely extend potentially suitable land and/or growing season.[93]

Changes in pests and diseases

Climate change is predicted to affect many potato pests and diseases. These include:

- Insect pests such as the potato tuber moth and Colorado potato beetle, which are predicted to spread into areas currently too cold for them.[87]

- Aphids which act as vectors for many potato viruses and will spread under increased temperatures.[97]

- Pathogens causing potato blackleg disease (e.g. Dickeya) grow and reproduce faster at higher temperatures.[98]

- Bacterial infections such as Ralstonia solanacearum will benefit from higher temperatures and spread more easily through flash flooding.[87]

- Late blight benefits from higher temperatures and wetter conditions.[99] Late blight is predicted to become a greater threat in some areas (e.g. in Finland)[87] and become a lesser threat in others (e.g. in the United Kingdom).[91]

Adaptation strategies

Shifting potato production from areas where yields will decline due to hotter temperatures and decreased water availability to places which will become suitable can help to mitigate much of the projected decline in yield: however, this can also trigger competition for land between potato crops and other crops or other land uses.),[95] mostly due to changes in water and temperature regimes. At the same time potato production is predicted to become possible in high altitude and latitude areas where it would previously have been limited by frost damage. These changes in crop yields are predicted to cause shifts in the areas in which potato crops can be viably produced.[95]

The other approach is through the development of varieties or cultivars which would be more adapted to altered conditions. This can be done through 'traditional' plant breeding techniques and genetic modification. These techniques allow for the selection of specific traits as a new cultivar is developed. Certain traits, such as heat stress tolerance, drought tolerance, fast growth/early maturation and disease resistance, may play an important role in creating new cultivars able to maintain yields under stressors induced by climate change.[96]

For instance, developing cultivars with greater heat stress tolerance would be critical for maintaining yields in countries with potato production areas near current cultivars' maximum temperature limits (e.g. Sub-Saharan Africa, India).[100] Superior drought resistance can be achieved through improved water use efficiency (amount of food produced per amount of water used) or the ability to recover from short drought periods and still produce acceptable yields. Further, selecting for deeper root systems may reduce the need for irrigation.[101] Finally, potatoes that grow faster could help adjust to shorter growing seasons in some areas, and reduce the number of life cycles that pests such as potato tuber moth can complete in a single growing season.[93]

Content

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 364 kJ (87 kcal) |

20.1 g | |

| Sugars | 0.9 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.8 g |

0.1 g | |

1.9 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 9% 0.11 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.02 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 9% 1.44 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 10% 0.52 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 18% 0.3 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 3% 10 μg |

| Vitamin C | 14% 13 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 0% 5 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.31 mg |

| Magnesium | 5% 22 mg |

| Manganese | 6% 0.14 mg |

| Phosphorus | 4% 44 mg |

| Potassium | 13% 379 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 4 mg |

| Zinc | 3% 0.3 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 77 g |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[102] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[103] | |

In a reference amount of 100 grams (3.5 oz), a boiled potato with skin supplies 87 calories and is 77% water, 20% carbohydrates (including 2% dietary fiber in the skin and flesh), 2% protein, and contains negligible fat (table). The protein content is comparable to other starchy vegetable staples, as well as grains.[104]

Boiled potatoes are a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin B6 (23% DV), and contain a moderate amount of vitamin C (16% DV) and B vitamins, such as thiamine, niacin, and pantothenic acid (10% DV each). Boiled potatoes do not supply significant amounts of dietary minerals (table).

The potato is rarely eaten raw because raw potato starch is poorly digested by humans.[105] Depending on the cultivar and preparation method, potatoes can have a high glycemic index (GI) and so are often excluded from the diets of individuals trying to follow a low-GI diet.[106][104] There is a lack of evidence on the effect of potato consumption on obesity and diabetes.[104]

In the UK, potatoes are not considered by the National Health Service as counting or contributing towards the recommended daily five portions of fruit and vegetables, the 5-A-Day program.[107]

Taste and smell

There are about 140 chemical compounds found in potato tubers which are responsible for their specific taste and smell. The most important are 1-octen-3-ol, (E)-2-octenol, (E)-2-octanal and geraniol as well as 2-Isopropyl-3-methoxypyrazine, which causes the "earthy" note in the smell and taste. The pyrazine compounds make up the aroma of baked potatoes.[108]

Toxicity

Raw potatoes contain toxic glycoalkaloids, of which the most prevalent are solanine and chaconine. Solanine is found in other plants in the same family, Solanaceae, which includes such plants as deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna), henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) and tobacco (Nicotiana spp.), as well as food plants like tomato. These compounds, which protect the potato plant from its predators, are concentrated in the aerial parts of the plant, in contrast to the tubers.[109][110]

Exposure to light, physical damage, and age increase glycoalkaloid content within the tuber.[111] Different potato varieties contain different levels of glycoalkaloids. The 'Lenape' variety, released in 1967, was withdrawn in 1970 as it contained high levels of glycoalkaloids.[112] Since then, breeders of new varieties test for this, sometimes discarding an otherwise promising cultivar. Breeders try to keep glycoalkaloid levels below 200 mg/kg (0.0032 oz/lb) (200 ppmw). However, when these commercial varieties turn green, they can still approach solanine concentrations of 1,000 mg/kg (0.016 oz/lb) (1000 ppmw). In normal potatoes, analysis has shown solanine levels at as little as 3.5% of the breeders' maximum, at 7–187 mg/kg (0.00011–0.00299 oz/lb).[113] While a normal potato tuber has 12–20 mg/kg (0.00019–0.00032 oz/lb) of glycoalkaloid content, a green potato tuber contains 250–280 mg/kg (0.0040–0.0045 oz/lb) and its skin has 1,500–2,200 mg/kg (0.024–0.035 oz/lb).[114]

Uses

Culinary

Potatoes are prepared in many ways: skin-on or peeled, whole or cut up, with seasonings or without. The only requirement involves cooking to swell the starch granules. Most potato dishes are served hot but some are first cooked, then served cold, notably potato salad and potato chips (crisps). Common dishes are: mashed potatoes, which are first boiled (usually peeled), and then mashed with milk or yogurt and butter; whole baked potatoes; boiled or steamed potatoes; French-fried potatoes or chips; cut into cubes and roasted; scalloped, diced, or sliced and fried (home fries); grated into small thin strips and fried as hash browns; grated and formed into dumplings, Rösti or potato pancakes.[115]

Potato dishes vary around the world. Peruvian cuisine naturally contains the potato as a primary ingredient in many dishes, as around 3,000 varieties of the tuber are grown there.[116] Chuño is a freeze-dried potato product traditionally made by Quechua and Aymara communities of Peru and Bolivia.[117] In the UK, potatoes form part of the traditional dish fish and chips. Roast potatoes are commonly served as part of a Sunday roast dinner and mashed potatoes form a major component of several other traditional dishes, such as shepherd's pie, bubble and squeak, and bangers and mash. New potatoes may be cooked with mint and are often served with butter.[118] In Germany, Northern (Finland, Latvia and especially Scandinavian countries), Eastern Europe (Russia, Belarus and Ukraine) and Poland, newly harvested, early ripening varieties are considered a special delicacy. Boiled whole and served un-peeled with dill, these "new potatoes" are traditionally consumed with Baltic herring. Puddings made from grated potatoes (kugel, kugelis, and potato babka) are popular items of Ashkenazi, Lithuanian, and Belarusian cuisine.[119] Cepelinai, the national dish of Lithuania, are dumplings made from boiled grated potatoes, usually stuffed with minced meat.[120] In Italy, in the Friuli region, potatoes serve to make a type of pasta called gnocchi.[121] Potato is used in northern China where rice is not easily grown, a popular dish being 青椒土豆丝 (qīng jiāo tǔ dòu sī), made with green pepper, vinegar and thin slices of potato. In the winter, roadside sellers in northern China sell roasted potatoes.[122]

-

Pommes frites, also called chips and French fries

-

Baked potato with sour cream and chives

-

German Bauernfrühstück ("farmer's breakfast")

Other uses

Potatoes are sometimes used to brew alcoholic spirits such as vodka, poitín, akvavit, and brännvin.[123][124]

Potatoes are widely used as fodder for livestock. Livestock-grade potatoes, known as "chats", are those considered too small or blemished to sell or market for human use, but suitable as fodder. They may be stored in bins or made into silage.[125]

Potato starch is used in the food industry as a thickener and binder for soups and sauces, in the textile industry as an adhesive, and in the paper industry for the manufacturing of papers and boards.[126][127]

Potatoes are commonly used in plant research. The consistent parenchyma tissue, the clonal nature of the plant and the low metabolic activity make it an ideal model tissue for experiments on wound-response studies and electron transport.[128]

Cultural significance

In mythology

According to Iroquois mythology, the first potatoes grew out of Earth Woman's feet after she died giving birth to her twin sons, Sapling and Flint.[129]

In art

The potato has been an essential crop in the Andes since the pre-Columbian era. The Moche culture from Northern Peru made ceramics from the earth, water, and fire. This pottery was a sacred substance, formed in significant shapes and used to represent important themes. Potatoes are represented anthropomorphically as well as naturally.[130] During the late 19th century, numerous images of potato harvesting appeared in European art, including the works of Willem Witsen and Anton Mauve.[131] Van Gogh's 1885 painting The Potato Eaters portrays a family eating potatoes. Van Gogh said he wanted to depict peasants as they really were. He deliberately chose coarse and ugly models, thinking that they would be natural and unspoiled in his finished work.[132] Jean-François Millet's The Potato Harvest depicts peasants working in the plains between Barbizon and Chailly. It presents a theme representative of the peasants' struggle for survival. Millet's technique for this work incorporated paste-like pigments thickly applied over a coarsely textured canvas.[133]

-

Girl peeling potatoes by Albert Anker, 1886, oil on canvas

-

The potato harvest by Jules Bastien-Lepage, 1877, National Gallery of Victoria

In popular culture

Invented in 1949, and marketed and sold commercially by Hasbro in 1952, Mr. Potato Head is an American toy that consists of a plastic potato and attachable plastic parts, such as ears and eyes, to make a face. It was the first toy ever advertised on television.[134]

See also

- Irish potato candy

- List of potato museums

- Loy (spade), a form of early spade used in Ireland for the cultivation of potatoes

- New World crops

- Potato battery

- International Year of the Potato

References

- ^ "Solanum tuberosum L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "patata". Diccionario Usual (in Spanish). Royal Spanish Academy. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ Ley, Willy (February 1968). "The Devil's Apples". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 118–25 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b J. Simpson; E. Weiner, eds. (1989). "potato, n". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8.

- ^ Weatherford, J. McIver (1988). Indian givers: how the Indians of the Americas transformed the world. New York: Fawcett Columbine. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-449-90496-1.

- ^ "spud (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "jordäpple | SAOB | svenska.se" (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Hooshmand, Dana (12 October 2020). ""Earth Apple": The 5 Languages that Use This for "Potato"". discoverdiscomfort.com. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Laws, Christopher (9 February 2015). "A Cultural History of the Potato as Earth Apple". Culturedarm. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Ewing, E. E.; Struik, P. C. (1992). "Tuber Formation in Potato: Induction, Initiation, and Growth". In Janick, Jules (ed.). Horticultural Reviews. pp. 89–198. doi:10.1002/9780470650523.ch3. ISBN 978-0-471-57339-5.

- ^ Amador, Virginia; Bou, Jordi; Martínez-García, Jaime; Monte, Elena; Rodríguez-Falcon, Mariana; Russo, Esther; Prat, Salomé (2001). "Regulation of potato tuberization by daylength and gibberellins" (PDF). International Journal of Developmental Biology (45): S37–S38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ Plaisted, R. (1982). "Potato". In W. Fehr & H. Hadley (ed.). Hybridization of Crop Plants. New York: American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America. pp. 483–494. ISBN 0-89118-034-6.

- ^ a b c d e Eggers, Ernst-Jan; Burgt, van der; Heusden, van; et al. (6 July 2021). "Neofunctionalisation of the Sli gene leads to self-compatibility and facilitates precision breeding in potato". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 4141. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.4141E. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24267-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8260583. PMID 34230471.

- ^ Hijmans, R.J.; Spooner, D.M. (2001). "Geographic distribution of wild potato species". American Journal of Botany. 88 (11): 2101–12. doi:10.2307/3558435. JSTOR 3558435. PMID 21669641.

- ^ a b c Spooner, David M.; McLean, Karen; Ramsay, Gavin; Waugh, Robbie; Bryan, Glenn J. (29 September 2005). "A single domestication for potato based on multilocus amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (41): 14694–14699. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214694S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507400102. PMC 1253605. PMID 16203994.

- ^ a b c Office of International Affairs (1989). Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-Known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. p. 92. doi:10.17226/1398. ISBN 978-0-309-04264-2.

- ^ a b c John Michael Francis (2005). Iberia and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History : a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 867. ISBN 978-1-85109-421-9.

- ^ Ames, M.; Spooner, D.M. (February 2008). "DNA from herbarium specimens settles a controversy about origins of the European potato". American Journal of Botany. 95 (2): 252–257. doi:10.3732/ajb.95.2.252. PMID 21632349. S2CID 41052277.

- ^ Martins-Farias 1976; Moseley 1975

- ^ Harris, David R.; Hillman, Gordon C. (2014). Foraging and Farming: The Evolution of Plant Exploitation. Routledge. p. 496. ISBN 978-1-317-59829-9.

- ^ a b Anabalón Rodríguez, Leonardo; Morales Ulloa, Daniza; Solano Solis, Jaime (July 2007). "Molecular description and similarity relationships among native germplasm potatoes (Solanum tuberosum ssp. tuberosum L.) using morphological data and AFLP markers". Electronic Journal of Biotechnology. 10 (3): 436–443. doi:10.2225/vol10-issue3-fulltext-14. hdl:10925/320. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ^ "Using DNA, scientists hunt for the roots of the modern potato". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Sauer, Jonathan (2017). Historical Geography of Crop Plants : a Select Roster. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-203-75190-9. OCLC 1014382952. ISBN 9780849389016 ISBN 9781351440622 ISBN 9781351440615 ISBN 9781351440639 ISBN 9780367449872

- ^ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2011). "The Potato's Contribution to Population and Urbanization: Evidence from a Historical Experiment" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 126 (2): 593–650. doi:10.1093/qje/qjr009. PMID 22073408. S2CID 17631317. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Nowicki, Marcin; Foolad, Majid R.; Nowakowska, Marzena; Kozik, Elzbieta U.; et al. (17 August 2011). "Potato and tomato late blight caused by Phytophthora infestans: An overview of pathology and resistance breeding". Plant Disease. 96 (1). American Phytopathological Society: 4–17. doi:10.1094/PDIS-05-11-0458. PMID 30731850.

- ^ Raker, Celeste M.; Spooner, David M. (2002). "Chilean Tetraploid Cultivated Potato, Solanum tuberosum is Distinct from the Andean Populations: Microsatellite Data" (PDF). Crop Science. 42. doi:10.2135/cropsci2002.1451. University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ "Cultivated Potato Genebank". International Potato Center. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Visser, R.G.F.; Bachem, C.W.B.; Boer, J.M.; et al. (2009). "Sequencing the Potato Genome: Outline and First Results to Come from the Elucidation of the Sequence of the World's Third Most Important Food Crop". American Journal of Potato Research. 86 (6): 417–29. doi:10.1007/s12230-009-9097-8.

- ^ Story is reprinted (with editorial adaptations by ScienceDaily staff) from materials provided by University of Wisconsin–Madison (4 February 2008). "Using DNA, Scientists Hunt For The Roots Of The Modern Potato". ScienceDaily (with information from a report originally appearing in the American Journal of Botany). Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ Song, J; Bradeen, J.M.; Naess, S.K.; Raasch, J.A.; Wielgus, S.M.; Haberlach, G.T.; Liu, J; Kuang, H; Austin-Phillips, S; Buell, C.R.; Helgeson, J.P.; Jiang, J (2003). "Gene RB cloned from Solanum bulbocastanum confers broad spectrum resistance to potato late blight". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (16): 9128–9133. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9128S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1533501100. PMC 170883. PMID 12872003.

- ^ Paluchowska, Paulina; Sliwka, Jadwiga; Yin, Zhimin (2022). "Late blight resistance genes in potato breeding". Planta. 255 (6). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 127. Bibcode:2022Plant.255..127P. doi:10.1007/s00425-022-03910-6. eISSN 1432-2048. ISSN 0032-0935. PMC 9110483. PMID 35576021.

- ^ a b Bradshaw, J.; Bryan, G.; Ramsay, G. (2006). "Genetic Resources (Including Wild and Cultivated Solanum Species) and Progress in their Utilisation in Potato Breeding". Potato Research. 49 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 49–65. doi:10.1007/s11540-006-9002-5. ISSN 0014-3065. S2CID 30648732.

- ^ Hosaka, Kazuyoshi; Hanneman, Robert E. Jr. (1998). "Genetics of self-compatibility in a self-incompatible wild diploid potato species Solanum chacoense. 1. Detection of an S locus inhibitor (Sli) gene". Euphytica. 99 (3): 191–197. doi:10.1023/a:1018353613431. ISSN 0014-2336. S2CID 40678039.

- ^ Ma, Ling; Zhang, Chunzhi; Zhang, Bo; et al. (6 July 2021). "A nonS-locus F-box gene breaks self-incompatibility in diploid potatoes". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 4142. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.4142M. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24266-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8260799. PMID 34230469.

- ^ Lindhout, Pim; Meijer, Dennis; Schotte, Theo; Hutten, Ronald C. B.; Visser, Richard G. F.; van Eck, Herman J. (2011). "Towards F1 Hybrid Seed Potato Breeding". Potato Research. 54 (4). Springer: 301–312. doi:10.1007/s11540-011-9196-z. ISSN 0014-3065. S2CID 39719359.

- ^ Angmo, Dechen; Sharma, Sat Pal; Kalia, Anu (2023). "Breeding strategies for late blight resistance in potato crop: recent developments". Molecular Biology Reports. 50 (9). Springer: 7879–7891. doi:10.1007/s11033-023-08577-0. ISSN 0301-4851. PMID 37526862. S2CID 260349512.

- ^ a b c Zierer, Wolfgang; Rüscher, David; Sonnewald, Uwe; Sonnewald, Sophia (17 June 2021). "Tuber and Tuberous Root Development". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 72 (1). Annual Reviews: 551–580. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-080720-084456. ISSN 1543-5008. PMID 33788583. S2CID 232482246.

- ^ Theisen, K (1 January 2007). "History and overview". World Potato Atlas: Peru. International Potato Center. Archived from the original on 14 January 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Potato Council. "Potato Varieties". Agriculture & Horticulture Development Board. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ "Potato Primer" (PDF). Cooks Illustrated. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Agricultural Marketing Service. "Potatoes for Chipping Grades and Standards". Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Creamer Potato". recipetips.com. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ "What is a new potato? New guidelines issued". BBC News. 12 August 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "A look back at a Royal history". 25 January 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "Europotato.org". Europotato.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ "So many varieties, so many choices". Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association. 2017.

- ^ Hirsch, C.N.; Hirsch, C.D.; Felcher, K; Coombs, J; Zarka, D; Van Deynze, A; De Jong, W; Veilleux, R.E.; Jansky, S; Bethke, P; Douches, D.S.; Buell, C.R. (2013). "Retrospective View of North American Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Breeding in the 20th and 21st Centuries". G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 3 (6): 1003–13. doi:10.1534/g3.113.005595. PMC 3689798. PMID 23589519.

- ^ Jemison, John M. Jr.; Sexton, Peter; Camire, Mary Ellen (2008). "Factors Influencing Consumer Preference of Fresh Potato Varieties in Maine". American Journal of Potato Research. 85 (2): 140. doi:10.1007/s12230-008-9017-3. S2CID 34297429.

- ^ Mattoo, A.K.; Shukla, V; Fatima, T; Handa, A.K.; Yachha, S.K. (2010). "Genetic Engineering to Enhance Crop-Based Phytonutrients (Nutraceuticals) to Alleviate Diet-Related Diseases". Bio-Farms for Nutraceuticals. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 698. pp. 122–43. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7347-4_10. ISBN 978-1-4419-7346-7. PMID 21520708.

- ^ "Genetically Engineered Organisms Public Issues Education Project/Am I eating GE potatoes?". Cornell University. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ "GMO compass database". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "GM potatoes: BASF at work". 31 May 2010. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010.

- ^ "Research in Germany: Business BASF applies for approval for another biotech potato". 2 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013.

- ^ Burger, Ludwig (10 November 2015). "BASF applies for EU approval for Fortuna GM potato | Reuters". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Oh, Soohyun; Choi, Doil (2022). "Receptor-mediated nonhost resistance in plants". Review. Essays in Biochemistry. 66 (5). Portland Press Limited (Biochemical Society): 435–445. doi:10.1042/EBC20210080. PMC 9528085. PMID 35388900. S2CID 247999992.

- ^ BASF stops GM crop development in Europe, Deutsche Welle, 17 January 2012

- ^ Kanter, James (16 January 2012). "BASF to Stop Selling Genetically Modified Products in Europe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 January 2024. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (7 November 2014). "U.S.D.A. Approves Modified Potato. Next Up: French Fry Fans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014.

- ^ "Consumer acceptance of genetically modified potatoes" (PDF). American Journal of Potato Research. 2002. cited through Bnet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Rosenthal, Elisabeth (24 July 2007). "A genetically modified potato, not for eating, is stirring some opposition in Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ United States Potato Board. "Seed Potatoes". Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Seed & Ware Potatoes". www.sasa.gov.uk. Scottish Agricultural Science Agency; Science & Advice for Scottish Agriculture. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ "Potatoes Home Garden". sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu. UF/IFAS Extension. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Jefferies, R. A.; Lawson, H. M. (1991). "A key for the stages of development of potato (Solanum tuberosum)". Annals of Applied Biology. 119 (2): 387–399. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1991.tb04879.x. ISSN 0003-4746.

- ^ "Growing Potatoes in the Home Garden" (PDF). Cornell University Extension Service. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Brulard, Maude (29 April 2015). "Dutch saltwater potatoes offer hope for world's hungry". M.phys.org. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Potatoes". The National Allotment Society. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Organic Management of Late Blight of Potato and Tomato (Phytophthora infestans)". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ "Potato, Identifying Diseases". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Potato Disease Identification". Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Alyokhin, A. (2009). "Colorado potato beetle management on potatoes: current challenges and future prospects" (PDF). In Tennant, P.; Benkeblia, N. (eds.). Potato II. Fruit, Vegetable and Cereal Science and Biotechnology 3 (Special Issue 1). pp. 10–19.

- ^ "Potato Cyst Nematode". Agriculture Victoria. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Ciaran Miceal; Auat Cheein, Fernando (22 May 2023). "Machinery for potato harvesting: a state-of-the-art review". Frontiers in Plant Science. 14. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1156734. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 10239890. PMID 37284722.

- ^ Kleinkopf G.E. and N. Olsen. 2003. Storage Management, in: Potato Production Systems, J.C. Stark and S.L. Love (eds), University of Idaho Agricultural Communications, pp. 363–381.

- ^ a b c Potato storage, value Preservation: Kohli, Pawanexh (2009). "Potato storage and value Preservation: The Basics" (PDF). CrossTree techno-visors. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ "Can eating burnt foods cause cancer?". Cancer Research UK. 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b Epp, Melanie (12 April 2021). "The Worry with CIPC". EuropeanSeed. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Potato production in 2021 Region/World/Production Quantity/Crops from pick lists". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division. 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021. Geneva: FAOSTAT. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb4477en. ISBN 978-92-5-134332-6. S2CID 240163091. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2010 data". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013.

- ^ Sarah Sinton (2011). "There's yet more gold in them thar "hills"!". Grower Magazine, The Government of New Zealand.

- ^ "Phosphate and potatoes". Ballance. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ "International Year of the Potato: 2008, Asia and Oceania". Potato World. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Workshop to Commemorate the International Year of the Potato. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2008.

- ^ Foley, Ramankutty; et al. (12 October 2011). "Solutions for a cultivated planet". Nature. 478 (7369): 337–42. Bibcode:2011Natur.478..337F. doi:10.1038/nature10452. PMID 21993620. S2CID 4346486.

- ^ Ensminger, Audrey; Ensminger, M.E.; Konlande, James E. (1994). Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia. CTC Press. p. 1104. ISBN 978-0-8493-8981-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Haverkort AJ, Verhagen A (October 2008). "Climate Change and Its Repercussions for the Potato Supply Chain". Potato Research. 51 (3–4): 223–237. doi:10.1007/s11540-008-9107-0. S2CID 22794078.

- ^ Zhao, Chuang; Liu, Bing; Piao, Shilong; Wang, Xuhui; Lobell, David B.; Huang, Yao; et al. (15 August 2017). "Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (35): 9326–9331. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.9326Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.1701762114. PMC 5584412. PMID 28811375.

- ^ "Potato". CIP. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Luck J, Spackman M, Freeman A, Trebicki P, Griffiths W, Finlay K, Chakraborty S (10 January 2011). "Climate change and diseases of food crops". Plant Pathology. 60 (1). British Society for Plant Pathology (Wiley-Blackwell): 113–121. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02414.x. ISSN 0032-0862.

- ^ a b "Climate change and potatoes: The risks, impacts and opportunities for UK potato production" (PDF). Cranfield Water Science Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Crop Water Information: Potato". FAO Water Development and Management Unit. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Climate change - can potato stand the heat?". WRENmedia. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Daccache A, Keay C, Jones RJ, Weatherhead EK, Stalham MA, Knox JW (2012). "Climate change and land suitability for potato production in England and Wales: impacts and adaptation". Journal of Agricultural Science. 150 (2): 161–177. doi:10.1017/s0021859611000839. hdl:1826/8188. S2CID 53488790.

- ^ a b c d Hijmans RJ (2003). "The Effect of Climate Change on Global Potato Production". American Journal of Potato Research. 80 (4): 271–280. doi:10.1007/bf02855363. S2CID 3355406.

- ^ a b Levy D, Veilleux RE (2007). "Adaptation of Potato to High Temperatures and Salinity A Review". American Journal of Potato Research. 84 (6): 487–506. doi:10.1007/bf02987885. S2CID 602971.

- ^ Pandey SK. "Potato Research Priorities in Asia and the Pacific Region". FAO. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Czajkowski R. "Why is Dickeya spp. (syn. Erwinia chrysanthemi) taking over? The ecology of a blackleg pathogen" (PDF). Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Forbes GA. "Implications for a warmer, wetter world on the late blight pathogen: How CIP efforts can reduce risk for low-input potato farmers" (PDF). CIP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Information highlights from World Potato Congress, Kunming, China, April 2004" (PDF). World Potato Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Potato and water resources". FAO. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Beals, Katherine A. (2019). "Potatoes, Nutrition and Health". American Journal of Potato Research. 96 (2): 102–110. doi:10.1007/s12230-018-09705-4.

- ^ Beazell, JM; Schmidt, CR; Ivy, AC (January 1939). "On the Digestibility of Raw Potato Starch in Man". The Journal of Nutrition. 17 (1): 77–83. doi:10.1093/jn/17.1.77.

- ^ Fernandes G, Velangi A, Wolever TM (2005). "Glycemic index of potatoes commonly consumed in North America". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 105 (4): 557–62. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.01.003. PMID 15800557.

- ^ "5 A Day: what counts?". nhs.uk. 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Reineccius, Gary, ed. (1993). Sourcebook of Flavors (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-8342-1307-9. S. 362.

- ^ "Tomato-like Fruit on Potato Plants". Iowa State University. Archived from the original on 16 July 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ Mendel Friedman, Gary M. McDonald & Mary Ann Filadelfi-Keszi (1997). "Potato Glycoalkaloids: Chemistry, Analysis, Safety, and Plant Physiology". Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 16 (1): 55–132. Bibcode:1997CRvPS..16...55F. doi:10.1080/07352689709701946.

- ^ "Greening of potatoes". Food Science Australia. 2005. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Koerth-Baker, Marggie (25 March 2013). "The case of the poison potato". boingboing.net. Archived from the original on 8 November 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Friedman, Mendel; Roitman, James N.; Kozukue, Nobuyuki (7 May 2003). "Glycoalkaloid and calystegine contents of eight potato cultivars". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (10): 2964–2973. doi:10.1021/jf021146f. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 12720378.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2005). Is it Safe to Eat?: Enjoy Eating and Minimize Food Risks. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 129. ISBN 978-3-540-21286-7.

- ^ b:Cookbook:Potato

- ^ Hayes, Monte (24 June 2007). "Peru Celebrates Potato Diversity". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ Timothy Johns: With bitter Herbs They Shall Eat it : Chemical ecology and the origins of human diet and medicine, The University of Arizona Press, Tucson 1990, ISBN 0-8165-1023-7, pp. 82–84

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Early Potato gets protected European status". BBC News. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ von Bremzen, Anya; Welchman, John (1990). Please to the Table: The Russian Cookbook. New York: Workman Publishing. pp. 319–20. ISBN 978-0-89480-845-6.

- ^ "D.E.L.A.C." delac.eu. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Roden, Claudia (1990). The Food of Italy. London: Arrow Books. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-09-976220-1.

- ^ Solomon, Charmaine (1996). Charmaine Solomon's Encyclopedia of Asian Food. Melbourne: William Heinemann Australia. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-85561-688-5.

- ^ Ermochkine, Nicholas and Iglikowski, Peter (2003). 40 degrees east : an anatomy of vodka, Nova Publishers, p. 65, ISBN 1-59033-594-5.

- ^ Brännvinsbränning Archived 21 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine in Nordisk familjebok, volume 4 (1905)

- ^ Halliday, Les; et al. (2015). "Ensiling Potatoes" (PDF). Prince Edward Island Agriculture and Fisheries. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Grant M. Campbell; Colin Webb; Stephen L. McKee (1997). Cereals: Novel Uses and Processes. Springer. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-306-45583-4.

- ^ Jai Gopal; S.M. Paul Khurana (2006). Handbook of Potato Production, Improvement, and Postharvest. Haworth Press. p. 544. ISBN 978-1-56022-272-9.

- ^ Espinoza, N. O.; Estrada, R.; Silva-Rodriguez, D.; Tovar, P.; Lizarraga, R.; Dodds, J. H. (1986). "The Potato: A Model Crop Plant for Tissue Culture". Outlook on Agriculture. 15 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1177/003072708601500104. ISSN 0030-7270.

- ^ Day, Ashley (20 November 2023). "3 Sisters to Invite to Thanksgiving". Food & Wine.

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York:Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ^ Steven Adams; Anna Gruetzner Robins (2000). Gendering Landscape Art. University of Manchester. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7190-5628-4.

- ^ van Tilborgh, Louis (2009). "The Potato Eaters by Vincent van Gogh". The Vincent van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ Johnston, W.R., Nineteenth Century Art: From Romanticism to Art Nouveau, The Walters Art Gallery, p.56, ISBN 1857592433

- ^ "Mr Potato Head". Museum of Childhood. V&A Museum of Childhood. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

Sources

- Economist. "Llamas and mash", The Economist 28 February 2008 online

- Economist. "The potato: Spud we like", (leader) The Economist 28 February 2008 online

- Boomgaard, Peter (2003). "In the Shadow of Rice: Roots and Tubers in Indonesian History, 1500–1950". Agricultural History. 77 (4): 582–610. doi:10.1525/ah.2003.77.4.582. JSTOR 3744936.

- Hawkes, J.G. (1990). The Potato: Evolution, Biodiversity & Genetic Resources, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC

- Lang, James (1975). Notes of a Potato Watcher. Texas A&M University Agriculture series. ISBN 978-1-58544-138-9.

- Langer, William L (1975). "American Foods and Europe's Population Growth 1750–1850". Journal of Social History. 8 (2): 51–66. doi:10.1353/jsh/8.2.51. JSTOR 3786266.

- McNeill, William H. "How the Potato Changed the World's History." Social Research (1999) 66#1 pp. 67–83. ISSN 0037-783X Fulltext: Ebsco, by a leading historian

- McNeill William H (1948). "The Introduction of the Potato into Ireland". Journal of Modern History. 21 (3): 218–21. doi:10.1086/237272. JSTOR 1876068. S2CID 145099646.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac. Black '47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory. (1999). 272 pp.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac, Richard Paping, and Eric Vanhaute, eds. When the Potato Failed: Causes and Effects of the Last European Subsistence Crisis, 1845–1850. (2007). 342 pp. ISBN 978-2-503-51985-2. 15 essays by scholars looking at Ireland and all of Europe

- Reader, John. Propitious Esculent: The Potato in World History (2008), 315pp a standard scholarly history

- Salaman, Redcliffe N. (1989) [1949. The History and Social Influence of the Potato, Cambridge University Press.

- Stevenson, W.R., Loria, R., Franc, G.D., and Weingartner, D.P. (2001) Compendium of Potato Diseases, 2nd ed, Amer. Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN.

- Zuckerman, Larry. The Potato: How the Humble Spud Rescued the Western World. (1998). 304 pp. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0-86547-578-4.

Further reading

- Bohl, William H.; Johnson, Steven B., eds. (2010). Commercial Potato Production in North America: The Potato Association of America Handbook (PDF). Second Revision of American Potato Journal Supplement Volume 57 and USDA Handbook 267. The Potato Association of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2012.

- "'Humble' Potato Emerging as World's Next Food Source". column. Japan. Reuters. 11 May 2008. p. 20.

- Spooner, David M.; McLean, Karen; Ramsay, Gavin; Waugh, Robbie; Bryan, Glenn J. (October 2005). "A single domestication for potato based on multilocus amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (41). National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America: 14694–14699. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214694S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507400102. PMC 1253605. PMID 16203994.

- The World Potato Atlas, released by the International Potato Center in 2006 and regularly updated.

- World Geography of the Potato at UGA.edu, released in 1993.

- Atlas of Wild Potatoes (2002), Systematic and Ecogeographic Studies on Crop Genepools 10, International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), ISBN 9789290435181

- Gauldie, Enid (1981). The Scottish Miller 1700–1900. Pub. John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-067-7.

External links

- Solanum tuberosum (potato, papas): life cycle, tuber anatomy at GeoChemBio. Archived 8 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

![Production of potatoes (2019)[79]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Production_of_potatoes_%282019%29.svg/622px-Production_of_potatoes_%282019%29.svg.png)