History of Azerbaijan: Difference between revisions

LouisAragon (talk | contribs) Rawaddids didn't rule above the Aras River. Same goes for Suhrawardi, Bahmanyar, and others who did NOT hail from what is the present-day Republic. Is this article meant to encompass the history of Aliyev's irredentist Butov Azarbaycan? |

LouisAragon (talk | contribs) - irredentism |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Azerbaijan sidebar}} |

{{Azerbaijan sidebar}} |

||

The '''history of Azerbaijan''' encompasses the Republic of Azerbaijan |

The '''history of Azerbaijan''' encompasses the Republic of Azerbaijan. During [[Media (region)|Median]] and Persian rule, many [[Caucasian Albania]]ns adopted [[Zoroastrianism]] before converting to [[Christianity]] prior to the arrival of the Muslim [[Arabs]] (particularly the Muslim Turks). The Turkic tribes are believed to have arrived as small bands of ''[[Ghazi (warrior)|ghazis]]'', whose conquests led to [[Turkification]] of the population as largely-native Caucasian and Iranian tribes adopted the language of the [[Oghuz Turks]] and converted to [[Islam]] over a period of several centuries.<ref>''Seyahatname'' by Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682)</ref> |

||

After the Russo-Persian wars of [[Russo-Persian War (1804–1813)|1804–1813]] and [[Russo-Persian War (1826–1828)|1826–1828]], the [[Qajar dynasty|Qajar Empire]] was forced to cede its Caucasian territories to the [[Russian Empire]]; the treaties of [[Treaty of Gulistan|Gulistan]] in 1813 and [[Treaty of Turkmenchay|Turkmenchay]] in 1828 defined the border between [[Tsardom of Russia|Czarist Russia]] and Qajar Iran.<ref>{{cite book|author=Harcave, Sidney|year=1968|title=Russia: A History: Sixth Edition|publisher=Lippincott|page=267}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz|year=2007|title=Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran: A Study of the Origin, Evolution, and Implications of the Boundaries of Modern Iran with Its 15 Neighbors in the Middle East by a Number of Renowned Experts in the Field|publisher=Universal|isbn=978-1-58112-933-5|page=372}}</ref> |

After the Russo-Persian wars of [[Russo-Persian War (1804–1813)|1804–1813]] and [[Russo-Persian War (1826–1828)|1826–1828]], the [[Qajar dynasty|Qajar Empire]] was forced to cede its Caucasian territories to the [[Russian Empire]]; the treaties of [[Treaty of Gulistan|Gulistan]] in 1813 and [[Treaty of Turkmenchay|Turkmenchay]] in 1828 defined the border between [[Tsardom of Russia|Czarist Russia]] and Qajar Iran.<ref>{{cite book|author=Harcave, Sidney|year=1968|title=Russia: A History: Sixth Edition|publisher=Lippincott|page=267}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz|year=2007|title=Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran: A Study of the Origin, Evolution, and Implications of the Boundaries of Modern Iran with Its 15 Neighbors in the Middle East by a Number of Renowned Experts in the Field|publisher=Universal|isbn=978-1-58112-933-5|page=372}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:08, 20 February 2021

| Part of the series on |

| Azerbaijan Azərbaycan |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| History |

| Demographics |

| Geography |

| Administrative divisions |

| Azerbaijan portal |

The history of Azerbaijan encompasses the Republic of Azerbaijan. During Median and Persian rule, many Caucasian Albanians adopted Zoroastrianism before converting to Christianity prior to the arrival of the Muslim Arabs (particularly the Muslim Turks). The Turkic tribes are believed to have arrived as small bands of ghazis, whose conquests led to Turkification of the population as largely-native Caucasian and Iranian tribes adopted the language of the Oghuz Turks and converted to Islam over a period of several centuries.[1]

After the Russo-Persian wars of 1804–1813 and 1826–1828, the Qajar Empire was forced to cede its Caucasian territories to the Russian Empire; the treaties of Gulistan in 1813 and Turkmenchay in 1828 defined the border between Czarist Russia and Qajar Iran.[2][3] The region north of the Aras was Iranian until it was occupied by Russia during the 19th century.[4][5][6][7][8][9] According to the Treaty of Turkmenchay, Qajar Iran recognized Russian sovereignty over the Erivan, Nakhchivan and Lankaran Khanates (the last parts of Azerbaijan still in Iranian hands).[10]

After more than 80 years of being part of the Russian Empire in the Caucasus, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was established in 1918. The name "Azerbaijan", adopted by the ruling Musavat Party for political reasons,[11][12] had been used to identify the adjacent region of northwestern Iran.[13][14][15] Azerbaijan was invaded by Soviet forces in 1920, and remained under Soviet rule until the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

Prehistory

Azerbaijani prehistory includes the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages. The Stone Age is divided into three periods: Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic.[16][17]

Paleolithic

The Paleolithic is divided into three periods: lower, middle, and upper. It began with the first human habitation in the region, and lasted until the 12th millennium BCE.[17]

The Azykh Cave in Fuzuli District is the site of one of Eurasia's oldest archaic-human habitations. Remnants of pre-Acheulean culture at least 700,000 years old were found in the lowest layers of the cave. In 1968, Mammadali Huseynov discovered a 300,000-year-old partial jawbone of an early human in its Acheulean-age layer; it was the oldest human remains ever discovered in the Soviet Union.[16][17][18][19]

Azerbaijan's lower Paleolithic, known for its Guruchay culture, has features similar to the culture of Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge.[20] The Paleolithic is also represented by finds at Aveidag, Tağlar and Damjily Caves, Zar, Yatagery, Dash Salakhly, Qazma and other sites.[citation needed]

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic, which lasted from approximately 12,000 to 8,000 BCE, is represented by caves in Gobustan National Park (near Baku) and Damjili (in Qazakh District).[16] Rock carvings in Gobustan depict hunting, fishing, work and dancing. Petroglyphs dating from 8,000 to 5,000 years ago depict long boats (similar to Viking ships), indicating a connection with Continental Europe and the Mediterranean Sea.[21][22]

Neolithic

The Neolithic, during the seventh and sixth millennia BCE, is represented by the Shulaveri-Shomu culture in Agstafa District; finds at Damjili, Gobustan, Kultepe (in Nakhchivan) and Toyretepe, and the Neolithic Revolution in agriculture.[16][23][24][25][26][27][28]

Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic (or Eneolithic), from the sixth to the fourth millennium BCE, was the period of transition from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age. The Caucasus Mountains are rich in copper ore, facilitating the development of copper smelting in Azerbaijan. A number of Chalcolithic settlements in Shomutepe, Toyratepe, Jinnitepe, Kultepe, Alikomektepe and IIanlitepe have been discovered, and carbon-dated artifacts indicate that inhabitants built homes, made copper tools and arrowheads, and were familiar with non-irrigated agriculture.[29]

Bronze and Iron Ages

The Bronze Age began in the second half of the fourth millennium BCE and ended in the second half of the second millennium BC in Azerbaijan, and the Iron Age began in about the seven and sixth centuries BCE. The Bronze Age is divided into three eras (early, middle and late), and have been studied in Nakhchivan, Ganja, Mingachevir and Dashkasan District.[30][31][32][33]

The early Bronze Age is characterized by the Kura–Araxes culture, and the middle Bronze Age by painted earthenware or pottery culture. The late Bronze Age is demonstrated in Nakhchivan and by the Khojali-Gadabay and Talish-Mugan cultures.[30][31][32]

Research in 1890 by Jacques de Morgan in the mountains of Talysh, near Lankaran, revealed over 230 late-Bronze and early-Iron Age burials. E. Rösler discovered late-Bronze Age materials in Karabakh and Ganja between 1894 and 1903. J. Hummel conducted research from 1930 to 1941 in Goygol District and Karabakh at sites known as Barrows I and II and other late-Bronze Age sites.[34][33][35]

Archaeologist Walter Crist of the American Museum of Natural History discovered a 4,000-year-old, Bronze Age version of hounds and jackals in Gobustan National Park in 2018. The game, popular in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Anatolia at the time, was identified in the tomb of Egyptian pharaoh Amenemhat IV.[36][37][38][39][40][41]

Caucasian Albanians may be the earliest known inhabitants of Azerbaijan.[42][full citation needed] Early invaders included the Scythians during the 9th century BCE.[43] The South Caucasus became part of the Achaemenid Empire around 550 BCE, and Zoroastrianism spread in Azerbaijan.

Antiquity

The Achaemenids were defeated by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE. After the 247 BCE fall of the Seleucid Empires in Persia, the Kingdom of Armenia ruled portions of Azerbaijan from 190 BCE to 428 CE.[44][45] The Arsacid dynasty of Armenia was a branch of the Parthian Empire, and Caucasian Albania (present-day Azerbaijan and Dagestan) was under Parthian rule for the next several centuries. The Caucasian Albanians established a kingdom in the 1st century BCE, primarily remaining a semi-independent vassal state until the Parthians were deposed in 252 and the kingdom became a province of the Sasanian Empire.[46][47][48] Caucasian Albania's King Urnayr adopted Christianity as the state religion during the fourth century, and Albania was a Christian state until the eighth century.[49][50] Although it was subordinate to Sasanid Persia, Caucasian Albania retained its monarchy.[51] Sasanid control ended with its 642 defeat by the Abbasid Caliphate[52] in the Muslim conquest of Persia.

The migration and settlement of Eurasian and Central Asian nomads has been a regional pattern in the history of the Caucasus from the Sassanid-Persian era to the 20th-century emergence of the Azerbaijani Turks. Among the Iranian nomads were the Scythians, Alans and Cimmerians, and the Khazars and Huns made incursions during the Hunnic and Khazar eras. Derbent was fortified during the Sasanid era to block nomads from beyond the North Caucasus pass who did not establish permanent settlements.[53]

Achaemenid and Seleucid rule

After the overthrow of the Median Empire, Azerbaijan was invaded by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BCE. This early Persian rule enabled the rise of Zoroastrianism and other Persian cultural influences. Many Caucasian Albanians came to be known as fire worshippers, a Zoroastrian practice.

The Achaemenid Empire lasted for over 250 years before it was conquered by Alexander the Great, leading to the rise of Hellenistic culture throughout the former Persian empire. The Seleucid Greeks inherited the Caucasus after Alexander's death in 323 BCE, but were beset by pressure from Rome, secessionist Greeks in Bactria, and the Parni: a nomadic East Iranian tribe who made inroads into the northeastern Seleucid domain from the late 4th to the 3rd century BCE; this allowed local Caucasian tribes to establish an independent kingdom for the first time since the Median invasion.

Caucasian Albania, Parthians, and Sasanian conquest

The Albanian kingdom coalesced around a Caucasian identity to forge a state in a region of empire-states. During the second or first century BCE the Armenians curtailed the southern Albanian territories and conquered Karabakh and Utik, inhabited by Albanian tribes who included the Utians, Gargarians and Caspians.[54][55] At this time, the border between Albania and Armenia was the Kura.[56][57]

As the region became an arena of wars when the Roman and Parthian Empires began to expand, most of Albania was briefly dominated by Roman legions under Pompey; the south was controlled by the Parthians. A rock carving of what is believed to be the easternmost Roman inscription, by Legio XII Fulminata during the reign of Domitian, survives just south-west of Baku in Gobustan. Caucasian Albania then came fully under Parthian rule.

In 252-253, Caucasian Albania was conquered and annexed by the Sasanian Empire. A vassal state, it retained its monarchy; the Albanian king had no real power, however, and most civil, religious, and military authority was held by the Sasanid marzban. After the Sasanid victory over Rome in 260, the victory and the annexation of Albania and Atropatene were described in a trilingual inscription by Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rostam.[58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65]

Urnayr (343-371), related by marriage to Shapur II (309-379), held power in Albania. With a somewhat-independent foreign policy, he allied with the Sasanian Shapur. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, the Albanians provided military forces (particularly cavalry) to Shapur's armies in their attacks against Rome. The siege of Amida (359) ended in a Sasanian victory, and some Albanian regions were returned. Marcellinus noted that the Albanian cavalry played a role in the siege similar to that of the Xionites, and the Albanians were commended for their alliance with Shapur:[64][49][62]

Close by him [Šapur II] on the left went Grumbates, king of the Chionitae, a man of moderate strength, it is true, and with shrivelled limbs, but of a certain greatness of mind and distinguished by the glory of many victories. On the right was the king of the Albani, of equal rank, high in honour[66]

After the 387 division of Armenia between Byzantium and Persia, the Albanian kings regained control of the provinces of Uti and Artsakh (south of the Kur) when the Sasanian kings rewarded them for their loyalty to Persia.[55][67]

Medieval Armenian historians such as Movses Khorenatsi and Movses Kaghankatvatsi wrote that the Albanians were converted to Christianity during the fourth century by Gregory the Illuminator of Armenia.[68][69] Urnayr accepted Christianity, was baptised by Gregory, and declared Christianity his kingdom's official religion.

The Mihranids (630-705) arrived in Albania from Gardman during the early seventh century. Partav (now Barda) was the dynasty's administrative centre. According to M. Kalankatli, the dynasty was founded by Mehran (570-590) and Varaz Grigor (628-642) assumed the title of "prince of Albania".[70][31]

Partav was Albania's capital city during the reign of Grigor's son, Javanshir (642-681), who demonstrated his allegiance early to Sasanian shah Yazdegerd III (632-651). He led the Albanian army as its sparapet from 636 to 642. Despite the Arab victory in the 637 battle of Kadissia, Javanshir fought as an ally of the Sasanians. After the 651 fall of the Sasanian Empire to an Arab caliphate, he shifted his allegiance to the Byzantine Empire three years later. Constans II protected Javanshir, who defeated the Khazars near the Kura in 662. Three years later the Khazars successfully attacked Albania, which became its tributary in exchange for the return of captives and cattle. Javanshir established diplomatic relations with the caliphate to protect his country from invasion via the Caspian Sea, meeting with Muawiyah I in Damascus in 667 and 670, and Albania's taxes were reduced. Javanshir was assassinated in 681 by rival Byzantine nobles. After his death, the Khazars again attacked Albania; Arab troops entered in 705 and put Javanshir's last heir to death in Damascus, ending the Mihrani dynasty and beginning caliphate rule.[71][72][73][74]

Middle Ages

Islamic conquest

Muslim Arabs defeated the Sasanian and Byzantine Empires as they marched into the Caucasus, making Caucasian Albania a vassal state after Javanshir's 667 surrender.[75][full citation needed] Between the ninth and 10th centuries, Arab authors began calling the region between the Kura and Aras "Arran".[76][full citation needed] Arabs from Basra and Kufa came to Azerbaijan, seizing abandoned lands.

At the beginning of the eighth century, Azerbaijan was the centre of the caliphate–Khazar–Byzantine wars. In 722–723, the Khazars attacked Arab Transcaucasian territory. An Arabian army led by Al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah drove the Khazars back across the Caucasus. Al-Jarrah fought his way north along the west Caspian coast, recovering Derbent and advancing with his army to the Khazar capital of Balanjar, captured the capital of the Khazar khanate and placed prisoners around Gabala. Then al-Jarrah returned to Sheki.[77][78][79]

During the ninth century, the Abbasid Caliphate dealt with uprisings against Arab rule. The Khurramites, led by Babak Khorramdin, staged a persistent revolt. Babak's victories over Arab generals were associated with his seizure of Babak Fort, according to Arab historians who said that his influence extended to Azerbaijan: "southward to near Ardabil and Marand, eastward to the Caspian Sea and the Shamakhi district and Shervan, northward to the Muqan (Moḡan) steppe and the Aras riverbank, westward to the districts of Jolfa, Nakjavan, and Marand".[80][81][82][83]

Seljuks

Azerbaijan's period as part of the Seljuk Empire may have been more pivotal than the Arab conquest, since it helped shape the identity of modern Azerbaijani Turks. At the beginning of the 11th century, the region was occupied by waves of Oghuz Turks from Central Asia. The first Turkic rulers were the Ghaznavids from northern Afghanistan, who took over part of Azerbaijan by 1030. They were followed by the Seljuks, a western branch of the Oghuz Turks who conquered Iran and the Caucasus. The Seljuks pressed on to Iraq, where they overthrew the Buyids in Baghdad in 1055.

The Seljuks then ruled an empire which included Iran and Azerbaijan until the end of the 12th century. During their rule, the sultan Nizam ul-Mulk (a noted Persian scholar and administrator) helped to introduce a number of educational and bureaucratic reforms. His death in 1092 began the decline of the Seljuk empire, which hastened after the death of sultan Ahmad Sanjar in 1153.

Seljuk possessions were ruled by atabegs, vassals of the Seljuk sultans who were sometimes de facto rulers themselves. The title of atabeg became common during Seljuk rule in the 12th century. From the end of the 12th to the early 13th century, Azerbaijan became a Turkic cultural centre. Palaces of the atabeg Eldiguz and the Shirvanshahs hosted distinguished guests, many of whom were Muslim artisans and scientists.

Under the Seljuks, progress was made in science and philosophy by Iranians such as Nizami Ganjavi and Khaqani, who lived in this region, mark the zenith of medieval Persian literature. The region experienced a building boom, and the unique Seljuk architecture is exemplified by the 12th-century fortress walls, mosques, schools, mausoleums, and bridges of Baku, Ganja and the Absheron Peninsula. In 1225, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu of the Khwarazmian dynasty ended Seljuk and atabeg rule.

Mongols and Ilkhanate rule

The Mongol invasion of the Middle East and the Caucasus impacted Azerbaijan and most of its neighbors. In 1231, the Mongols occupied most of Azerbaijan and killed Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu. Four years later, they destroyed cities of Ganja, Shamkir, Tovuz, and Şabran on their way to Kievan Rus'. By 1236, Transcaucasia was in the hands of Ögedei Khan.

End of Mongol rule and Kara Koyunlu-Aq Qoyunlu rivalry

Timur (Tamurlane) invaded Azerbaijan during the 1380s, temporarily incorporating it into his Eurasian domain. Shirvan, under Ibrahim I of Shirvan, was also a vassal state of Timur and assisted him in his war with the Mongol ruler Tokhtamysh of the Golden Horde. Azerbaijan experienced social unrest and religious strife during this period due to sectarian conflict initiated by Hurufism, the Bektashi Order and other movements.

After Timur's death in 1405, Shah Rukh (his fourth son) reigned until his death in 1447. Two rival Turkic rulers emerged west of his domain: the Kara Koyunlu (based around Lake Van) and the Aq Qoyunlu, centred around Diyarbakır. The Kara Koyunlu were ascendant when their chief, Qara Yusuf, overcame Sultan Ahmed Mirza (the last of the Jalayirids), conquered lands south of Azerbaijan in 1410, and established his capital at Tabriz. Under Jahan Shah, they expanded into central Iran and as far east as Greater Khorasan. The Aq Qoyunlu became prominent under Uzun Hasan, overcoming Jahan Shah and the Kara Koyunlu in 1468. Uzun Hasan ruled Iran, Azerbaijan and Iraq until his death in 1478. The Aq Qoyunlu and Kara Koyunlu continued the Timurid tradition of literary and artistic patronage, illustrated by Tabriz' Persian miniature paintings.

The Shirvanshahs

Shirvanshah, Shīrwān Shāh[84] or Sharwān Shāh,[84] was the title of the rulers of Shirvan: a Persianized dynasty[84] of Arabic origin.[84] The Shirvanshahs maintained a high degree of autonomy as local rulers and vassals from 861 to 1539, a continuity which lasted longer than any other dynasty in the Islamic world. Shirvan was reportedly independent during two periods: under the legendary sultan Manuchehr and Akhsitan I (who built Baku), and under the 15th-century House of Derbent. Between the 13th and 14th centuries, the Shirvanshahs were vassals of the Mongol and Timurid empires.

The Shirvanshahs Khalilullah I and Farrukh Yassar presided over a stable period during the mid-15th century, and Baku's Palace of the Shirvanshahs (which includes mausoleums) and the Khalwati Sufi khanqah were built during their reign. The Shirvanshahs were Sunnis, and opposed to the Shia Islam of the Safavid order. The Safavid leader Shaykh Junayd was killed in a 1460 skirmish with the Shirvanishah, leading to sectarian animosity.

Safavids and the rise of Shi'a Islam

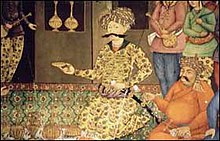

Detail from a ceiling fresco; Chehel Sotoun palace; Isfahan

The Safavid (Safaviyeh) was a Sufi religious order centred in Iran and formed in the 1330s by Sheikh Safi Al-Din (1252–1334), after whom it was eponymously named.

This Sufi order openly converted to the heterodox branch of Twelver Shi'a Islam by the end of the 15th century. Some Safavid followers, most notably the Qizilbash, believed in the mystical and esoteric nature of their rulers and their relationship to the house of Ali, and thus, were zealously predisposed to fight for them. The Safavid rulers claimed to be descended from Ali himself and his wife Fatimah, daughter of Muhammad, through the seventh Imam Musa al-Kazim. Qizilbash numbers increased by the 16th century and their generals were able to wage a successful war against the Ak Koyunlu state and capture Tabriz.

The Safavids, led by Ismail I, expanded their base in Ardabil, conquering the Caucasus, parts of Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Central Asia, and western parts of South Asia. During the same period, Ismail sacked Baku in 1501 and persecuted the Sunni Shirvanshahs. The territory of nowadays Azerbaijan was conquered by the Iranian Safavids, alongside Armenia and Dagestan, between 1500 and 1502.[85]

During the reign of Ismail I and his son Tahmasp, Shi'a Islam was imposed upon the formerly Sunni population of Iran and Azerbaijan. The imposition of Shi'a Islam was especially harsh in Shirvan, where a large Sunni population was massacred. Safavid Iran became a feudal theocracy during this period and the Shah was held to be the divinely ordained head of state and religion. During this period, the Qizilbashi chiefs were designated wakils (or legal administrators) with offices in charge of provincial administration and the class of Shia Islamic Ulema was created.

The wars with the Sunni Ottoman Empire, the archrivals of the Safavids, continued during the reign of Shah Tahmasp. The important Safavid cities of Shamakha, Ganja and Baku were occupied by Ottomans in the 1580s.

Under the reign of Shah Abbas I the Great (1587–1630) the monarchy peaked and took on a distinctly Persian national identity that merged with Shi'a Islam. Abbas I's reign represented the high point of development of the state and he was able to repel the Ottomans and re-capture the entire Caucasus, including what is now Azerbaijan and Shirvan in 1603. Being aware of the interfering power of the Qizilbash, he continued the same policy as his predecessors namely fully integrated the Caucasus and its elements into Persian society. To fulfil this, he deported hundreds of thousands of Circassians, Georgians and Armenians to Iran, who rose to high and low ranks in the army, royal house, and civil administration, effectively killing the feudal Qizilbash as these converted Caucasians (often called ghulams) had full allegiance to the Shah, and not their tribal chiefs, unlike the Qizilbash. Their descendants continue to linger forth in Iran, such as along the Iranian Armenians, Iranian Georgians and the Iranian Circassians.

The religious impact of the Safavids was furthermore huge on both contemporary Iran and Azerbaijan, as the population of Azerbaijan was forcibly converted to Shiism in the early 16th century at the same time as the people of what is nowadays Iran, when the Safavids held sway over it.[86] And the territory of modern-day Azerbaijan, therefore, contains the second largest population of Shia Muslims by percentage right after Iran,[87] and the two are the only nations where the population is by utter majority, nominally, Shia Muslim.

18th- and early 19th-century khanates and Iran's cession to Russia

While civil conflicts took hold in Iran, most of Azerbaijan was shortly occupied by the Ottomans (1722 to 1736).[88] Meanwhile, (from 1722 until 1735), during the reign of Peter the Great, the coastal strip along the Caspian Sea comprising Derbent, Baku and Salyan, came shortly under Imperial Russian rule through the Russo-Persian War (1722-1723).

After the collapse of the Safavid empire, Nadir Shah Afshar, an Iranian military genius of Turcoman origin came into power. He wrested control over Iran, banished the Afghans for good in 1729, and proceeded to go on an ambitious military spree, conquering as far as east as Delhi, and having the dream of founding another great Persian Empire. Not fortifying his Persian base severely exhausted his army. Nadir had effective control over Shah Tahmasp II and then ruled as the Regent of the infant Abbas III, until 1736, when he had himself crowned as Shah. The coronation of Nadir Shah took place in Mughan, in the present territory of Azerbaijan. Nader was a military genius, conquering in a short amount of time a new native Iranian empire encompassing a territory it had not seen since the time of the Sassanids. He conquered all of the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, parts of Anatolia, large parts of Central Asia, and crushed the Mughals in the Battle of Karnal, having free entrance to their capital Delhi, which he completely sacked and looted, bringing huge wealth with him back to Persia. His empire, however, was quite short-lived, but nevertheless he is considered the last great ruler of Asia.

After Nadir Shah's assassination in 1747, the Persian Empire under the Afsharids disintegrated. Several Muslim Turkic khanates with various forms of autonomy emerged in the area.[89][90][91][92][93] The former eunuch Agha Muhammad Khan of the Qajars could now turn to the restoration of the outlying provinces of the Safavid and Afsharid kingdom. Returning to Tehran in the spring of 1795, he assembled a force of some 60,000 cavalries and infantry and in Shawwal Dhul-Qa'da/May, set off for Azerbaijan, intending to reconquer all lost territories to the Ottomans and Russians, including the country between the rivers Aras and Kura, formerly under Iranian Safavid/Afsharid control. This region comprised a number of khanates of which the most important was Qarabagh, with its capital at Shusha; Ganja Khanate, with its capital of the same name; Shirvan Khanate across the Kura, with its capital at Shamakhi; and to the north-west, on both banks of the Kura, Christian Georgia (Gurjistan), with its capital at Tiflis,[94][95][96] while remaining under nominal Persian suzerainty.[95][97][98][99] The khanates engaged in constant warfare between themselves and with external threats. The most powerful among the northern khans was Fat'h Ali Khan of Quba (died 1783), who managed to unite most of the neighbouring khanates under his rule and even mounted an expedition to take Tabriz, fighting with Zand dynasty. Another powerful khanate was that of Karabakh, which subdued neighbouring Nakhchivan khanate and parts of Erivan khanate.

Agha Mohammad Khan emerged victorious out of the civil war that commenced with the death of the last Zand king. His reign is noted for the re-emergence of a centrally led and united Iran. After the death of Nader Shah and the last of the Zands, most of Iran's Caucasian territories had broken away and formed various Caucasian khanates. Agha Mohammad Khan, like the Safavid kings and Nader Shah before him, viewed the region as no different than the territories in Iran proper. Therefore, his first objective after having secured Iran was to reincorporate the Caucasus region into Iran.[100] Georgia was seen as one of the most integral territories.[101] For Agha Mohammad Khan, the re-subjugation and reintegration of Georgia into the Iranian Empire was part of the same process that had brought Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tabriz under his rule.[101] As the Cambridge History of Iran states, its permanent secession was inconceivable and had to be resisted in the same way as one would resist an attempt at the separation of Fars or Gilan.[101] It was therefore natural for Agha Mohammad Khan to do whatever was necessary in the Caucasus to subdue and reincorporate the recently lost regions following Nader Shah's death and the demise of the Zands, including putting down what in Iranian eyes was seen as treason on the part of the wali of Georgia, namely, the Georgian king Erekle II (Heraclius II) who was appointed viceroy (wali) of Georgia by Nader Shah himself.[101]

Agha Mohammad Khan subsequently demanded that Heraclius II renounce the treaty with Russia which had been signed several years earlier. This treaty had formally denounced any dependence on Persia and had agreed to full Russian protection and assistance in its affairs. Agha Mohammad Khan demanded that Heraclius II accept Persian suzerainty once more,[100] in return for peace and the security of his kingdom. The Ottomans, Iran's neighbouring rival, recognized the latter's rights over Kartli and Kakheti for the first time in four centuries.[102] Heraclius appealed then protector under the treaty, Empress Catherine II of Russia, seeking the support of at least 3,000 Russian troops,[102] but he got no response, leaving Georgia to fend off the Persian threat alone.[103] Nevertheless, Heraclius II still rejected the Khan's ultimatum.[104] In response, Agha Mohammad Khan invaded the Caucasus region after crossing the Aras River, and, while on his way to Georgia, he re-subjugated the territories of the Erivan Khanate, Shirvan, Nakhchivan Khanate, Derbent Khanate, Talysh Khanate, Shaki Khanate, Karabakh Khanate, which comprise modern-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Dagestan, and Igdir. Having reached Georgia with his large army, the Battle of Krtsanisi took place, which resulted in the capture and sack of Tbilisi, as well as the effective re-subjugation of Georgia into Iran.[105][106] Upon his return from his successful campaign in Tbilisi and in effective control over Georgia, together with some 15,000–20,000 Georgian captives who were taken back to Iran,[103][107] Agha Mohammad was formally crowned Shah in 1796 on the Mughan Plain, just like his predecessor Nader Shah had been about sixty years earlier.

Agha Mohammad Shah was later assassinated while preparing a second expedition against Georgia in 1797 in Shusha[108] (nowadays part of the Republic of Azerbaijan) and King Heraclius died early in 1798. Iranian hegemony over Georgia did not last long. In 1799 the Russians marched into Tbilisi.[109] The Russians were already actively occupied with an expansionary policy towards its neighbouring empires to its south, namely the Ottoman Empire and the successive Iranian kingdoms since the late 17th/early 18th century. The next two years following Russia's entrance into Tbilisi were a time of confusion. The weakened and devastated Georgian kingdom, with its capital half in ruins, was easily absorbed by Russia in 1801.[103][104] As Iran could not permit or allow the cession of Transcaucasia and Dagestan, which had formed part of the concept of Iran for centuries,[110] it would also become the direct cause of the wars that took place several years later, namely the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828), which would eventually lead to the irrevocable forced cession and loss of what is nowadays eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan to Imperial Russia through the treaties of Gulistan of 1813 and Turkmenchay of 1828, as the ancient ties could only be severed by a superior force from outside.[108][105] The Russo-Persian War (1804–1813) led to significant losses of life and property in Dagestan and the South Caucasus which disrupted trade and agriculture. The region, however, was mostly spared during the War of 1826–1828, as most of the fighting took place in Iranian territory.[111] As a consequence of the wars, long-standing ties between Iran and the region were severed during the course of the 19th century as Russia incorporated territory in the region.[112]

According to Professor Tadeusz Swietochowski:

The brief and successful Russian campaign of 1812 was concluded with the Treaty of Gulistan, which was signed on October 12 of the following year. The treaty provided for the incorporation into the Russian Empire of vast tracts of Iranian territory, including Daghestan, Georgia with the Sheragel province, Imeretia, Guria, Mingrelia, and Abkhazia (latter four regions were vassals of Ottomans), as well as the khanates of Karabagh, Ganja, Sheki, Shirvan, Derbent, Kuba, Baku, and Talysh.

According to Svante Cornell:

In 1812 Russia ended a war with Turkey and went on the offensive against Iran. This led to the treaty of Gulistan in 1813, which gave Russia control over large territories that hitherto had been at least nominally Iranian, and moreover a say in Iranian succession politics. The whole of Daghestan and Georgia, including Mingrelia and Abkhazia, were formally ceded to Russia, as well as eight Khanates in modern-day Azerbaijan (Karabakh, Ganja, Sheki, Kuba, Shirvan, Talysh, Baku, and Derbent). However, as we have seen the Persians soon challenged Russia's rule in the area, resulting in a military disaster. Iran lost control over the whole of Azerbaijan, and with the Turkemenchai settlement of 1828 Russia threatened to establish its control over Azerbaijan unless Iran paid a war indemnity. The British helped the Iranians with the matter, but the fact remained that Russian troops had marched as far as south of Tabriz. Although certain areas (including Tabriz) were returned to Iran, Russia was in fact at the peak of its territorial expansion.[96]

According to the Cambridge History of Iran:

Even when rulers on the plateau lacked the means to effect suzerainty beyond the Aras, the neighbouring Khanates were still regarded as Iranian dependencies. Naturally, it was those Khanates located closest to the province of Āzarbāījān which most frequently experienced attempts to re-impose Iranian suzerainty: the Khanates of Erivan, Nakhchivān and Qarābāgh across the Aras, and the cis-Aras Khanate of Ṭālish, with its administrative headquarters located at Lankarān and therefore very vulnerable to pressure, either from the direction of Tabrīz or Rasht. Beyond the Khanate of Qarābāgh, the Khān of Ganja and the Vāli of Gurjistān (ruler of the Kartli-Kakheti kingdom of south-east Georgia), although less accessible for purposes of coercion, were also regarded as the Shah's vassals, as were the Khāns of Shakki and Shīrvān, north of the Kura river. The contacts between Iran and the Khanates of Bākū and Qubba, however, were more tenuous and consisted mainly of maritime commercial links with Anzalī and Rasht. The effectiveness of these somewhat haphazard assertions of suzerainty depended on the ability of a particular Shah to make his will felt, and the determination of the local khans to evade obligations they regarded as onerous.[113]

Transition from Iranian rule to Russian rule

Russo-Persian Wars; and Treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchai (1828)

Audrey L. Altstadt argues that Russian military actions towards the Caucasus were already on since 1790, but the first war Russo-Persian War was 1804. (1804–13) The commander-in-chief appointed by Russia was infamous Pavel Tsitsianov, called ''ishpokdor'' meaning "his work is dirt", or "shedder of blood" by Iranian chronicler Muriel Atkin. Tsitsianov's main destructions took place in the historical city of Ganja now in Azerbaijan, including the change of city's name to Elizavetpol. He has functioned from 1803 to 1806 until his assassination in Baku.

Following their defeat by Russia, Qajar Iran was forced to sign the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, which acknowledged the loss of Dagestan, Georgia and most of Azerbaijan territory to Russia. Local khanates were either abolished (like in Baku or Ganja) or accepted Russian patronage. The end of Russo-Persian war in 1813 was marked with the Treaty of Gulistan.[114]

Another Russo-Persian war in 1826–28 resulted in another defeat for the Iranian army. The Russians dictated another infamous final settlement as per the Treaty of Turkmenchay, which resulted in the Qajars of Persia ceding their last remaining Caucasian territories in 1828, comprising the last parts of the modern-day Azerbaijani Republic that were still in the latter's hands (Nakhchivan, Lankaran Khanate) as well as modern-day Armenia (Erivan Khanate). Besides these changes in administration and sovereignty of khanates, the treaty of Turkmenchai had articles concerning the tariffs, especially of lowering the tariffs for the possibility of a flow of Russian goods; and on legal concessions such that grants Russia the right to keep a navy in the Caspian Sea. These articles also delineated the framework of Russian and Iran relations till 1917.[114]

The treaty established the current borders of Azerbaijan and Iran as the rule of local khans ended. Thus, the modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan was to be eventually created out of the integral territories of Iran that were taken by Russia in the course of the 19th century and was directly the result of it. In the newly Russian-controlled territories, two provinces were established that later constituted the bulk of the modern Republic – Elisavetpol (Ganja) province in the west, and Shamakha province in the east. The area to the North of the river Aras, among which the territory of the contemporary Republic of Azerbaijan was Iranian territory until they were occupied by Russia in the course of the 19th century.[4][5][6][7][8][9] As a direct result of Imperial Russia's annexations of Iranian territory in the Caucasus, which included the modern-day Azerbaijan Republic, the Azerbaijani people are nowadays split between Azerbaijan and Iran.[115] Following Russia's conquest sparked a large exodus of Caucasian Muslims towards the newly established borders of Iran, which included many Azerbaijanis from north of the Aras River.

Administration after 1828

From the time of the Russian Russian conquests through to the 1840s, Azerbaijan was governed by the Tsar's military forces. Russia reorganized the region's khanates into new provinces, each presided over by an army officer. The officers governed through a combination of local and Russian law. However, due to the officers' general unfamiliarity with local customs, Russian imperial law was increasingly applied, this led to discontent among the local populace.[116] Russian administration was not equal towards non-Christian Azerbaijanis, and the religious authorities were kept under control and this created disturbance among non-Christian citizens. The Azerbaijani Turks were affected by Russian restrictions against non-Christians. The Russian state made concerted efforts to control the application of Islamic law in the empire. Two Ecclesiastical Boards were created to oversee all religious Islamic activity. The state-appointed a mufti for the Sunni board and a sheikh al-Islam for the Shia. In 1857 Georgian and Armenian religious authorities were given oversight in censoring their respective communities, however, Muslim religious works and books had to be approved by a censorship board in Odessa. Additionally, Azerbaijani Turks were subject to intense Russian proselytization.[116]

In the late 1830s plans were made to replace the military rule by officers with a civil administration. When the new legal system came into effect in January 1841, Transcaucasia was divided into a Georgian-Imeretian province, and a Caspian oblast centered in Shamakhi. New administrative borders were later drawn that ignored historical borders or ethnic composition. By the end of military rule in Azerbaijan, Russian imperial law achieved hegemony in all criminal and most civil matters. The jurisdiction of traditional religious courts and qadis were reduced to family law. The Russian state made concerted efforts to control the application of Islamic law in the empire. As a result of a catastrophic earthquake in 1859, the capital of the eastern province was transferred from Shamakhi to Baku[114] which attained greater importance over time.

Baku

After the treaty of Gulistan in 1813, Baku was fully integrated into the Russian Empire. The years after the Russian conquest, Azerbaijan saw significant economic development, especially in the city of Baku after the second half of the 19th century.[117] The separate currencies of the former khanates were replaced by the ruble and the tariffs between them were abolished. These reforms encouraged further investment in the region. Russia started investing joint-stock companies in the region and by the 1840s the steamships first sailed on the Caspian. The port of Baku saw an increase from an average of 400,000 rubles of trade in the 1830s to an average of 500,000 in the 1840s and between 700,000 and 900,000 rubles in the wake of the Crimean War.[118]

Though oil was discovered and exported from the area centuries prior, the Azeri oil rush of the 1870s led to a period of unprecedented prosperity and growth in the years leading to World War I but also created huge disparities in wealth between the largely European capitalists and the local Muslim work force.[114] Starting in the 1870s Baku experienced an era of rapid industrial growth as a result of an oil boom. Azerbaijan's first oil refinery was established near Baku in 1859, and the region's first kerosene plant was erected in 1863. Wells built in the 1870s sparked the boom. Oil bearing lands were soon auctioned off to bidders. This system secured investors’ property and encouraged further investment in their holdings’ operations. Most of the people to acquire oil lands were elite Russians and Armenians, by the contrast of 51 plots sold at the first auction only 5 were bought by Azerbaijani Turks. Additionally of 54 oil extraction firms in Baku in 1888, only 2 notable companies were owned by Azerbaijanis. Azerbaijani Turks participated in greater numbers among small-scale extraction and refining operations. 73 of 162 oil refineries were Azerbaijani owned, but all but 7 of them were employed less than 15 people.[119] In the decades following the oil rush and foreign investment other industries grew in Azerbaijan. The banking system was one of the first to react to the oil industry In 1880 an offshoot of the state bank opened in Baku, in the first year of operation it issued 438,000 rubles, in 1899 all Baku banking institutions had issued 11.4 million rubles in all interest-bearing securities. Transportation and shipping industries also grew as a result of the expanding oil market. The number of vessels on the Caspian quadrupled between 1887 and 1899. The Transcaucasian Railway, completed in 1884, connected Baku on the Caspian coast to Batum on the Black Sea coast via Ganja (Elizavetpol) and Tiflis.[120] In addition to transporting oil, the railroad served to develop new relationships between rural agricultural areas and industrial zones.[120] The connectivity of the region was further increased by the implementation of new communication infrastructure, with telegraph lines connecting Baku to Tiflis via Ganja (Elizavetpol) in the 1860s, and a telephone system operating within Baku in the 1880s.[120]

The rush was spurred by Armenian oil magnate Mirzoev and his drilling practices, which were then replaced by the auction of oil lands, most of which were purchased by Russians and Armenians, followed by Europeans, most notably Robert Nobel of Branobel.[114] By 1900, the population of Baku increased from 10,000 to roughly 250,000 people as a result of worker migration from all over the Russian Empire, Iran, and other places. The growth of Baku and the progression of an exploitative economy resulted in the emergence of an Azeri nationalist intelligentsia that was educated and influenced by European and Ottoman ideas. Influential thinkers like Hasan bey Zardabi, Mirza Fatali Akhundov and later, Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, Mirza Alakbar Sabir, Nariman Narimanov and others spurred a nationalist discourse and rallied against poverty, ignorance, extremism and sought reforms in education and the emancipation of the dispossessed classes, including women. The financial support of philanthropist millionaires such as Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev also bolstered the rise of an Azeri middle-class.

Following the disastrous Russo-Japanese war, an economic and political crisis erupted in Baku, starting with a general strike of oil workers in 1904. In 1905, class and ethnic tensions resulted in Muslim-Armenian ethnic rioting during the first Russian Revolution. The Tsarist governments had, in fact, exploited ethnic and religious strife to maintain control in a policy of divide and rule.

The situation improved during 1906–1914 when a limited parliamentary system was introduced in Russia and Muslim MPs from Azerbaijan were actively promoting Azeri interests. In 1911, the pan-Turkist and pan-Islamist Musavat Party,[121][122][123][124][125][126] inspired by the left of centre modernizing ideology espoused by Mammed Amin Rasulzade, was formed. Founded clandestinely, the party expanded rapidly in 1917, after the overthrow of the Tsarist regime in Russia. The most essential components of the Musavat ideology were secularism, nationalism, and federalism, or autonomy within a broader political structure. However, the party's right- and left-wings differed on certain issues, most notably land distribution. The leader of the party was the left-leaning Mammed Amin Rasulzade.

After Russia became involved in World War I, social and economic tensions spiked again. The Russian Revolution of 1917 ultimately led to the granting of rights to the local population of the territory that nowadays constitutes Azerbaijan and the granting of self-rule, but this autonomy also led to renewed ethnic conflict between ethnic Azeris and Armenians.

Azerbaijan Democratic Republic

At the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, the Transcaucasian Republic was founded with the leading Armenian and Georgian intelligentsia. After a short span of time, the republic was dissolved, and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was proclaimed on 28 May 1918 by the leading Azeri Musavat party. The name of "Azerbaijan", which the leading Musavat party adopted, for political reasons,[11][12] was prior to the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918 exclusively used to identify the adjacent region of contemporary northwestern Iran.[13][14][127]

This was the first Democratic Republic established in Islamic World. In Baku, however, a coalition of Bolsheviks, Dashnaks and Mensheviks fought against a Turkish-Islamic army led by Nuru Pasha. This coalition known as the "Baku Commune" also inspired or tacitly condoned the massacres of local Muslims by well-armed Dashnak-Armenian forces. This coalition, however, collapsed and was replaced by a British-controlled government known as Central Caspian Dictatorship in July 1918. As a result of battles in August–September, on September 15, 1918 the joint forces of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and Ottoman Empire led by Nuru Pasha entered Baku and declared the city as a capital of young Azerbaijani state. This event has always been considered one of the most honourable pages of the Azerbaijani history.[128]

Azerbaijan was proclaimed a secular republic and its first parliament opened on December 5, 1918. British administration initially did not recognize the Republic but tacitly cooperated with it. By mid-1919 the situation in Azerbaijan had more or less stabilized, and British forces left in August 1919. However, by early 1920, advancing Bolshevik forces, victorious in Russian Civil War, started to pose a great threat to young republic, which also engaged in a conflict with Armenia over the Karabakh.

Azerbaijan received de facto recognition by the Allies as an independent nation in January 1920 at the Versailles Paris Peace Conference. The republic was governed by five cabinets, all formed by a coalition of the Musavat and other parties including the Socialist Bloc, the Independents, the Liberals, the Social-Democratic Party Hummat (or Endeavor) Party and the Conservative Ittihad (Union) Party. The premier in the first three cabinets was Fatali Khan Khoyski; in the last two, Nasib Yusifbeyli. The president of the parliament, Alimardan Topchubashev, was recognized as the head of state. In this capacity, he represented Azerbaijan at the Versailles Paris Peace Conference in 1919.

Aided by Azeri dissidents in the Republican government, the Red Army invaded Azerbaijan on April 28, 1920. The bulk of the newly formed Azerbaijani army was engaged in putting down an Armenian revolt that had just broken out in Karabakh. The Azeris did not surrender their brief independence of 1918–20 quickly or easily. As many as 20,000 died resisting what was effectively a Russian reconquest.[129] However, it has to be noticed that the installation of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic was made easier by the fact that there was certain popular support for Bolshevik ideology in Azerbaijan, in particular among the industrial workers in Baku.[130] The same day a Soviet government was formed under Nariman Narimanov. Before the year was over, the same fate had befallen Armenia, and, in March 1921, Georgia as well.

Soviet Azerbaijan

After the surrender of the national government to Bolshevik forces, Azerbaijan was proclaimed a Soviet Socialist Republic on April 28, 1920. Shortly after, the Congress of the Peoples of the East was held in September 1920 in Baku. Although formally an independent state, the Azerbaijan SSR was dependent upon and controlled by the government in Moscow. It was incorporated into the Transcaucasian SFSR along with Armenia and Georgia in March 1922. By an agreement signed in December 1922, the TSFSR became one of the four original republics of the Soviet Union. The TSFSR was dissolved in 1936 and its three regions became separate republics within the USSR.

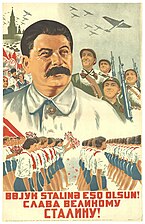

Like other union republics, Azerbaijan was affected by Stalin's purges in the 1930s. During that period, sometimes referred to as the "Red Terror", thousands of people were killed, including notable Azeri figures such as Huseyn Javid, Mikail Mushvig, Ruhulla Akhundov, Ayna Sultanova and others. Directing the purges in Azerbaijan was Mir Jafar Baghirov, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan, who followed Stalin's orders without question.[citation needed] His special target was the intelligentsia, but he also purged Communist leaders who had sympathized with the opposition or who might have once leaned toward Pan-Turkism[citation needed] or had contacts with revolutionary movements in Iran or Turkey.

During the 1940s, the Azerbaijan SSR supplied much of the Soviet Union's gas and oil during the war with Nazi Germany and was thus a strategically important region. The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 reached the Greater Caucasus in July 1942, but the Germans never crossed into the territory of Azerbaijan. Many Azerbaijanis fought well in the ranks of the Soviet Army[citation needed] (about 600–800,000) and Azeri Major-General Azi Aslanov was awarded twice Hero of the Soviet Union. About 400,000 Azeris died in World War II. The Germans also made fruitless efforts to enlist the cooperation of emigre political figures, most notably Mammed Amin Rasulzade. [citation needed]

Policies of de-Stalinization and improvement after the 1950s led to better education and welfare conditions for most of Azerbaijan.[citation needed] This also coincided with the period of rapid urbanization and industrialization. During this period of change, a new wave of sblizheniye (reapproachement) policy was instituted in order to merge all the peoples of the U.S.S.R. into a new monolithic Soviet nation.

In the 1960s, the signs of a structural crisis in the Soviet system began to emerge.[citation needed] Azerbaijan's crucial oil industry lost its relative importance in the Soviet economy, partly because of a shift of oil production to other regions of the Soviet Union and partly because of the depletion of known oil resources on land, while offshore production was not deemed cost-effective. As a result, Azerbaijan had the lowest rate of growth in productivity and economic output among the Soviet republics, with the exception of Tajikistan. Ethnic tensions, particularly between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, began to grow, but violence was suppressed.

In an attempt to end the growing structural crisis, in 1969, the government in Moscow appointed Heydar Aliyev as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan. Aliyev temporarily improved economic conditions and promoted alternative industries to the declining oil industry, such as cotton. He also consolidated the republic's ruling elite, which now consisted almost entirely of ethnic Azeris, thus reverting the previous trends at "rapprochement". In 1982, Aliyev was made a member of the Communist Party's Politburo in Moscow, the highest position ever attained by an Azeri in the Soviet Union. In 1987, when Perestroika started, he was forced[citation needed] to retire by the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev whose policies Aliyev opposed.

The late 1980s, during the Gorbachev era, were characterized by increasing unrest in the Caucasus, initially over the Nagorno-Karabakh issue. A political awakening came in February 1988 with the renewal of the ethnic conflict, which centered on Armenian demands for the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast of Azerbaijan SSR Armenia by March 1988, while pogroms of the Armenian population in Baku and Sumgait took place. Russia forced enforced military rule on several occasions but unrest continued to spread.

The ethnic strife revealed the shortcomings of the Communist Party as a champion of national interests, and, in the spirit of glasnost, independent publications and political organizations began to emerge. Of these organizations, by far the most prominent was the Popular Front of Azerbaijan (PFA),[citation needed] which by the fall of 1989 seemed poised to take power from the Communist Party. The PFA soon experienced a split between a conservative-Islamic wing and a moderate wing. The split was followed by an outbreak of anti-Armenian violence in Baku and intervention by Soviet troops.

Unrest culminated in violent confrontation when Soviet troops killed 132 nationalist demonstrators in Baku on January 20, 1990. Azerbaijan declared its independence from the USSR on August 30, 1991, and became part of the Commonwealth of Independent States. By the end of 1991, fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh had escalated into a full-scale war, which culminated into a tense cease-fire that has persisted into the 21st century. Although a cease-fire was achieved, the refusal to negotiate by both sides resulted in a stalemate as Armenian troops retained their positions in Karabakh as well as corridors taken from Azerbaijan that connect the enclave to Armenia.

Independent Azerbaijan

Mutalibov presidency (1991–1992)

While during 1990–1991 Azerbaijan gave more sacrifices in a struggle for independence from the USSR than any other Soviet republic,[citation needed] the declaration of independence introduced by President Ayaz Mutalibov on August 30, 1991, followed the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt. Mütallibov becomes the only Soviet leader besides Zviad Gamsakhurdia to endorse the Soviet coup attempt by issuing a statement from Tehran, while later dissolving the Communist Party of Azerbaijan and proposing constitutional changes for direct nationwide elections of the president.

On September 8, 1991, the first nationwide presidential elections, in which Mutalibov was the only running candidate, were held in Azerbaijan. While the elections were neither free nor fair by international standards, Mutalibov formally became the elected president of Azerbaijan. The adoption of the declaration of independence by the Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan SSR on October 18, 1991, was followed by a dissolution of the Azerbaijani Communist Party. However, its former members, including President Ayaz Mutalibov, retained their political posts.

In December 1991 in a nationwide referendum, Azerbaijani voters approved the Declaration of Independence adopted by the Supreme Council; with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan is recognized as an independent state at first by Turkey, Israel, Romania and Pakistan. The United States followed suit on December 25.

Meanwhile, the conflict over Nagorno Karabakh continued despite the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Early in 1992, Karabakh's Armenian leadership proclaimed an independent republic. In what was now a full-scale war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Armenians gained the upper hand, with covert assistance from the Russian Army. Major atrocities were committed by both sides, with the Khojaly massacre of Azerbaijani civilians on February 25, 1992, causing a social uproar over the government inaction (also was the Maragha Massacre, in which Azeris killed indigenous Armenian civilians). Mütallibov was forced to submit his resignation to the National Assembly of Azerbaijan on March 6, under pressure from the Azerbaijan Popular Front.

Mutalibov's failure to build up an adequate army, that he feared may not remain under his control, brought about the downfall of his government. On May 6 the last Azerbaijani-populated town in Nagorno-Karabakh, Shusha, falls under Armenian control. On May 14 the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan hears the case on the Khojaly Massacre, relieves Mütallibov of any responsibility, reverses his prior resignation and restores him as the President of Azerbaijan, but the day after, May 15, armed forces led by the Azerbaijan Popular Front take control of the offices of the Parliament of Azerbaijan and Azerbaijani State Radio and Television, thereby deposing Mütallibov, who leaves for Moscow; the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan is dissolved passing the duties to the National Assembly of Azerbaijan formed by equal representation of Azerbaijan Popular Front and former communists. Two days later, while Armenian forces take control of Lachin, Isa Gambar is elected as the new Chairman of the National Assembly of Azerbaijan and takes on the temporary duties of President of Azerbaijan until the national elections due on June 17, 1992.

Elchibey presidency (1992–1993)

The former Communists failed to present a viable candidate at the 1992 elections and Abulfaz Elchibey, the leader of the Popular Front of Azerbaijan (PFA) and former dissident and political prisoner, was elected president with more than 60% of the vote. His program included opposition to Azerbaijan's membership in the Commonwealth of Independent States, closer relations with Turkey, and a desire for extended links with the Iranian Azerbaijanis.

Heydar Aliyev, who had been prevented from running for president by an age limit of 65, was doing well in Nakhchivan. He had to contend with an Armenian blockade of Nakhchivan. In turn, Armenia suffered when Azerbaijan halted all rail traffic into and out of Armenia, cutting most of its land links with the outside world. The negative economic effects of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict seemed to illustrate the interdependence of the Transcaucasian nations.

Within a year after his election, President Elchibey came to face the same situation that had led to the downfall of Mutalibov. The fighting in and around Nagorno Karabakh steadily turned in favour of the Armenians, who seized around one-fifth of Azerbaijan's territory, creating more than a million internally displaced persons. A military rebellion against Abulfaz Elchibey broke out in early June 1993 in Ganja under the leadership of Colonel Surat Huseynov. The Popular Front of Azerbaijan leadership found itself without political support as a result of the war's setbacks, a steadily deteriorating economy, and opposition from groups led by Heydar Aliyev. In Baku, Aliyev seized the reins of power and quickly consolidated his position. A confidence referendum in August deprived Elchibey of his post.

Heydar Aliyev presidency (1993–2003)

On 3 October 1993 a presidential election was held, and Aliyev won overwhelmingly. By March 1994, Aliyev was able to get rid of some of his opposition including Surat Huseynov, who was arrested along with other rivals. In 1995, the former military police were accused of plotting a coup and disbanded. Coup plotters were linked to right wing Turkish nationalists. Later, in 1996 Rəsul Quliyev, former speaker of parliament went into self-imposed exile. Thus, by end of 1996, the position of Heydar Aliyev as an absolute ruler in Azerbaijan was unquestionable.

As a result of limited reforms and the signing of the so-called "Contract of The Century" in October 1994 (over the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli giant oil field) that led to increased oil exports to western markets, the economy began improving. However, extreme levels of corruption and nepotism in the state system created by Aliyev prevented Azerbaijan from more sustained development, especially in the non-oil sector.

In October 1998, Aliev was re-elected as president for a second term. Weakened opposition accused him of voter fraud, but no widespread international condemnation of the elections followed. His second term in office was characterized by limited reforms, increasing oil production and the dominance of British Petroleum as a main foreign oil company in Azerbaijan. In early 1999, a giant Shah Deniz gas field was discovered making Azerbaijan potentially a major gas exporter. A gas export agreement was signed with Turkey by 2003. Work on a long-awaited Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline and Baku-Tbilisi-Erzerum gas pipeline started in 2003. The oil pipeline was completed in 2005 and the gas pipeline in 2006. Azerbaijan is also a party to the proposed Nabucco Pipeline.

Heydar Aliyev fell ill and, in April 2003, collapsed on stage and could not return to public life. By summer 2003 he was placed into intensive care in the United States where he was pronounced dead on December 12, 2003.

Ilham Aliyev presidency (2003)

In yet another controversial election, his son Ilham Aliyev was elected president the same year. The election was characterized by mass violence and was criticised by foreign observers. Presently, political opposition to the Aliyev administration remains strong. Many were not satisfied with this new dynastical succession and were pushing for a more democratic government. Ilham Aliyev was re-elected in 2008 with 87% of the polls, while opposition parties boycotted the elections. In a constitutional referendum in 2009, term limits for the presidency were abolished and freedom of the press was restricted.

The 2010 parliamentary elections produced a Parliament completely loyal to Aliyev: for the first time in Azerbaijani history, not a single candidate from the main opposition Azerbaijan Popular Front or Musavat parties was elected. The Economist scored Azerbaijan as an authoritarian regime, placing it 135th out of 167 countries, in its 2010 Democracy Index.

Repeated protests were staged against Aliyev's rule in 2011, calling for democratic reforms and the ouster of the government. Aliyev has responded by ordering a security crackdown, using force to crush attempts at revolt in Baku, and refusing to make concessions. Well over 400 Azerbaijanis have been arrested since protests began in March 2011.[131] Opposition leaders, including Musavat's Isa Gambar, have vowed to continue demonstrating, although police have encountered little difficulty in stopping protests almost as soon as they began.[132]

On 24 October 2011 Azerbaijan was elected as a non-permanent member to United Nations Security Council.[133][134] The term of office began on January 1, 2012.

Between 1 and 5 April 2016, there were renewed clashes between Armenian and Azerbaijani armed forces. (see 2016 Armenian–Azerbaijani clashes).

See also

- Azerbaijan

- Dissolution of the Soviet Union

- History of Armenia

- History of Georgia

- History of Iran

- Azerbaijan (Iran)

- History of Russia

- History of Turkey

- History of the Caucasus

- History of Europe

- Origin of the Azerbaijanis

- Politics of Azerbaijan

- President of Azerbaijan

- Western Azerbaijan (political concept)

- Goytepe archaeological complex

- Early Middle Ages in Azerbaijan

Notes

- ^ Seyahatname by Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682)

- ^ Harcave, Sidney (1968). Russia: A History: Sixth Edition. Lippincott. p. 267.

- ^ Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz (2007). Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran: A Study of the Origin, Evolution, and Implications of the Boundaries of Modern Iran with Its 15 Neighbors in the Middle East by a Number of Renowned Experts in the Field. Universal. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-58112-933-5.

- ^ a b Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. pp. 69, 133. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3.

- ^ a b L. Batalden, Sandra (1997). The newly independent states of Eurasia: handbook of former Soviet republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89774-940-4.

- ^ a b E. Ebel, Robert, Menon, Rajan (2000). Energy and conflict in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7425-0063-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Andreeva, Elena (2010). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and orientalism (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-78153-4.

- ^ a b Çiçek, Kemal, Kuran, Ercüment (2000). The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-975-6782-18-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ernest Meyer, Karl, Blair Brysac, Shareen (2006). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-465-04576-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 728–729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ a b Yilmaz, Harun (2015). National Identities in Soviet Historiography: The Rise of Nations Under Stalin. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-1317596646.

On May 27, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan (DRA) was declared with Ottoman military support. The rulers of the DRA refused to identify themselves as [Transcaucasian] Tatar, which they rightfully considered to be a Russian colonial definition. (...) Neighboring Iran did not welcome did not welcome the DRA's adoptation of the name of "Azerbaijan" for the country because it could also refer to Iranian Azerbaijan and implied a territorial claim.

- ^ a b Barthold, Vasily (1963). Sochineniya, vol II/1. Moscow. p. 706.

(...) whenever it is necessary to choose a name that will encompass all regions of the republic of Azerbaijan, name Arran can be chosen. But the term Azerbaijan was chosen because when the Azerbaijan republic was created, it was assumed that this and the Persian Azerbaijan will be one entity, because the population of both has a big similarity. On this basis, the word Azerbaijan was chosen. Of course right now when the word Azerbaijan is used, it has two meanings as Persian Azerbaijan and as a republic, its confusing and a question rises as to which Azerbaijan is talked about.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Atabaki, Touraj (2000). Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and the Struggle for Power in Iran. I.B.Tauris. p. 25. ISBN 9781860645549.

- ^ a b Dekmejian, R. Hrair; Simonian, Hovann H. (2003). Troubled Waters: The Geopolitics of the Caspian Region. I.B. Tauris. p. 60. ISBN 978-1860649226.

Until 1918, when the Musavat regime decided to name the newly independent state Azerbaijan, this designation had been used exclusively to identify the Iranian province of Azerbaijan.

- ^ Rezvani, Babak (2014). Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan: academisch proefschrift. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-9048519286.

The region to the north of the river Araxes was not called Azerbaijan prior to 1918, unlike the region in northwestern Iran that has been called since so long ago.

- ^ a b c d Azərbaycan Arxeologiyası- Daş Dövrü I cild (PDF). Şərq-Qərb. 2008.

- ^ a b c Baxşəliyev, Vəli (2006). Azərbaycan Arxeologiyası (PDF). Bakı. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-11. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ^ "Azerbaijan — History and Culture". www.iexplore.com. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ^ "Jawbones and Dragon Legends: Azerbaijan's Prehistoric Azikh Cave by Dr. Arif Mustafayev". azer.com. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ^ "Visions of Azerbaijan Magazine ::: A History of Azerbaijan: from the Furthest Past to the Present Day". Visions of Azerbaijan Magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ^ "Gobustan Rock Art - World Heritage Site - Pictures, Info and Travel Reports". www.worldheritagesite.org. Retrieved 2020-03-17.

- ^ Coimbra, Fernando, ed. (2008). Cognitive Archaeology as Symbolic Archaeology. England: BAR Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9781407301792.

- ^ Alakbarov, V.A (2018). "TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE NEOLITHIC POTTERY AT GÖYTEPE (WEST AZERBAIJAN)". Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia. 46 (3): 22–31. doi:10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.3.022-031. ISSN 1563-0110.

- ^ Nıshıakı, Yoshıhıro; Guliyev, Farhad (2015). "Chronological context of the earliest pottery Neolithic in the South Caucasus : Radiocarbon. Dates for Göytepe and Hacı Elemxanlı Tepe, Azerbaijan" (PDF). American Journal of Archaeology. 119 (3): 279–294. doi:10.3764/aja.119.3.0279.

- ^ Nishiaki; Kannari; Nagai; Maeda (2019). "Obsidian provenance analyses at Göytepe, Azerbaijan: Implications for understanding Neolithic socioeconomies in the southern Caucasus: Obsidian provenance analyses at Göytepe, Azerbaijan". Archaeometry. doi:10.1111/arcm.12457.

- ^ Guliyev, Farhad; Yoshihiro, Nishiaki (2012). "Excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Göytepe, the middle Kura Valley, Azerbaijan, 2008-2009". ResearchGate. 3: 71–84.

- ^ Nishiaki Seiji, Yoshihiro; Guliyev, Farhad; Kadowaki, Seiji (2015). "The origins of food production in the southern Caucasus: excavations at Hacı Elamxanlı Tepe, Azerbaijan". Antiquity. 89: 348.

- ^ Archaeological researches in Azerbaijan 2015-2016. Baku: Arxeologiya və Etnoqrafiya İnstitutu. 2017. ISBN 978-9952-473-05-6.

- ^ Sebbane, Michael (1989). "COPPER METALLURGY, TRADE AND THE URBANIZATION OF. SOUTHERN CANAAN IN THE CHALCOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE 1". Academia.edu.

- ^ a b "ARCHEOLOGY viii. REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ a b c Zerdabli, Ismail bey (2014). THE HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN. Rossendale Books.

- ^ a b ISMAILOV, DILGAM (2017). HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (PDF). Baku.

- ^ a b Göyüşov, Rəşid (1986). Azərbaycan Arxeologiyası (PDF).

- ^ Palumbi, Giulio (2016). "The Early Bronze Age of the Southern Caucasus". Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935413.013.14.

- ^ JAFARLI, Hidayat (2016). "Bronze Age and Early Iron Age monuments of Karabakh" (PDF). İrs Karabakh: 22–29.

- ^ "4,000-Year-Old Board Game Called 58 Holes Discovered in Azerbaijan | Mysterious Universe". mysteriousuniverse.org. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ December 2018, Tom Metcalfe 10. "4,000-Year-Old Game Board Carved into the Earth Shows How Nomads Had Fun". livescience.com. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "4,000-Year-Old Game Board Identified in Azerbaijan - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ Whelan, Ed. "Holes Found Carved in Ancient Rock Shelter in Azerbaijan Belong to One of World's Oldest Games". www.ancient-origins.net. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ "A 4,000-Year-Old Bronze Age Game Called 58 Holes Has Been Discovered In Azerbaijan Rock Shelter". WSBuzz.com. 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ "A Bronze Age game was found chiseled into stone in Azerbaijan". Science News. 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ^ Historical Dictionary

- ^ Azerbaijan – US Library of Congress Country Studies (retrieved 7 June 2006).

- ^ "Armenia-Ancient Period" – US Library of Congress Country Studies (retrieved 23 June 2006)

- ^ Strabo, "Geography" – Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University (retrieved 24 June 2006).

- ^ p. 38

- ^ James Stuart Olson. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. ISBN 0-313-27497-5

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: "The list of provinces given in the inscription of Ka'be-ye Zardusht defines the extent of the empire under Shapur, in clockwise geographic enumeration: (1) Persis (Fars), (2) Parthia, (3) Susiana (Khuzestan), (4) Maishan (Mesene), (5) Asuristan (southern Mesopotamia), (6) Adiabene, (7) Arabistan (northern Mesopotamia), (8) Atropatene (Azerbaijan), (9) Armenia, (10) Iberia (Georgia), (11) Machelonia, (12) Albania (eastern Caucasus), (13) Balasagan up to the Caucasus Mountains and the Gate of Albania (also known as Gate of the Alans), (14) Patishkhwagar (all of the Elburz Mountains), (15) Media, (16) Hyrcania (Gorgan), (17) Margiana (Merv), (18) Aria, (19) Abarshahr, (20) Carmania (Kerman), (21) Sakastan (Sistan), (22) Turan, (23) Mokran (Makran), (24) Paratan (Paradene), (25) India (probably restricted to the Indus River delta area), (26) Kushanshahr, until as far as Peshawar and until Kashgar and (the borders of) Sogdiana and Tashkent, and (27), on the farther side of the sea, Mazun (Oman)"

- ^ a b "Albania" – Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. I, p. 807 (retrieved 15 June 2006).

- ^ "Voices of the Ancients: Heyerdahl Intrigued by Rare Caucasus Albanian Text" by Dr. Zaza Alexidze Archived 2009-01-17 at the Wayback Machine – Azerbaijan International, Summer 2002 (retrieved 7 June 2006).

- ^ Nevertheless, "despite being one of the chief vassals of Sasanian Shahanshah, the Albanian king had only a semblance of authority, and the Sassanid marzban (military governor) held most civil, religious, and military authority.

- ^ "Islamic Conquest."

- ^ pp. 385–386

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H., Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians, in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity, Chico: 1982, 27–40.

- ^ a b Vladimir Minorsky. A History of Sharvān and Darband in the 10th–11th Centuries.

- ^ See: Strabo, Geography, 11.5 (English ed. H. C. Hamilton, Esq., W. Falconer, M.A.); also: Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, (eds. John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley).

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. Armenia: a Historical Atlas. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2001

- ^ "ALBANIA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ "SASANIAN DYNASTY – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Vladimir Minorsky. A History of Sharvan and Darband in the 10th-11th Centuries.

- ^ "Ancient Iran". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ a b "Widok Caucasian Albanian Warriors in the Armies of pre-Islamic Iran | Historia i Świat". czasopisma.uph.edu.pl. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Zardabli, Ismail bey (2014). THE HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN: from ancient times to the present day. Lulu.com. p. 61. ISBN 9781291971316.

- ^ a b A. West, Barbara (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 9781438119137.

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan, ed. (1983). The Cambridge History of Iran. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521200929.

- ^ Marcellinus, Ammianus (1939). ROLFE, J.C (ed.). The later Roman Empire. Cambridge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ M. Chaumont, "Albania, Ancient country in Caucasus" Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ^ Moses Khorenatsi. History of the Armenians, translated from Old Armenian by Robert W. Thomson. Harvard University Press, 1978

- ^ Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of the Land of Aluank, translated from Old Armenian by Sh. V. Smbatian. Yerevan: Matenadaran (Institute of Ancient Manuscripts), 1984

- ^ ISMAILOV, DILGAM (2017). HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (PDF). Baku: Nəşriyyat – Poliqrafiya Mərkəzi.

- ^ "CTESIPHON – Encyclopaedia Iranica". web.archive.org. 2016-05-17. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Brummell, Paul (2005). Turkmenistan. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841621449.

- ^ "ḴOSROW II – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781845116453.

- ^ p. 71

- ^ p. 20

- ^ Dunlop, D. M. (2012-04-24). "al-D̲j̲arrāḥ b. ʿAbd Allāh". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition.

- ^ Yahya Blankinship, Khalid (1994). The End of the Jihad State: The Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. SUNY Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780791418277.

- ^ Alan Brook, Kevin (2006). The Jews of Khazaria. 126: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442203020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Babak Khorramdin Saeid Nafisi - [PDF Document]". vdocuments.mx. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- ^ "BĀBAK ḴORRAMI – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- ^ "ḴORRAMIS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-09-09.