Roman Republic: Difference between revisions

Pmanderson (talk | contribs) rvt to CSCWEM |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

<!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: [[Image:LocationRomanRepublic.png|right|frame]] --> |

<!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: [[Image:LocationRomanRepublic.png|right|frame]] --> |

||

{{See|Roman province}} |

{{See|Roman province}} |

||

The city of [[Rome]] itself stands on the banks of the river [[Tiber]], very near the west coast of [[Italy]]. It marked the border between the regions of [[Latium]] (the territory in which the Latin language and culture was dominant) to the south, and [[Etruria]] (the territory in which the [[Etruscan]] language and culture was dominant) to the north |

The city of [[Rome]] itself stands on the banks of the river [[Tiber]], very near the west coast of [[Italy]]. It marked the border between the regions of [[Latium]] (the territory in which the Latin language and culture was dominant) to the south, and [[Etruria]] (the territory in which the [[Etruscan]] language and culture was dominant) to the north. |

||

The Roman republic would expand outwards from this single city state. Eventually it would include all of the [[Italian peninsula]], large parts of [[Gaul]] and [[Hispania]], much of the Greek peninsula, parts of the [[Illyricum|Balkans]], coastal regions of [[Asia (province)|Asia Minor]], part of the north [[Africa (province)|African]] coastline, [[Corsica et Sardinia|Corsica]], [[Corsica et Sardinia|Sardina]], and [[Sicilia (Roman province)|Sicily]]. |

The Roman republic would expand outwards from this single city state. Eventually it would include all of the [[Italian peninsula]], large parts of [[Gaul]] and [[Hispania]], much of the Greek peninsula, parts of the [[Illyricum|Balkans]], coastal regions of [[Asia (province)|Asia Minor]], part of the north [[Africa (province)|African]] coastline, [[Corsica et Sardinia|Corsica]], [[Corsica et Sardinia|Sardina]], and [[Sicilia (Roman province)|Sicily]]. |

||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

Each time Rome conquered new lands, the territory would be sectioned off into one or more [[Roman provinces|provinces]], under the administration of a [[Roman governor]], chosen annually by the Senate. He would be awarded a [[Promagistrate|promagisterial]] rank, either [[proconsul]]ar or [[propraetor]]ial, depending on the size and importance of the province (see [[Roman provinces]] for list of governor's ranks). In the later Republic, newly acquired land was often partly used to settle the discharged veterans of the military campaign who had earned their "land grant". This not only "paid off" the army, but had the added benefit of settling Roman people, with Roman customs, bringing Roman culture to newly conquered people: a form of "cultural imperialism" as well as a military one (See: [[Romanization (cultural)|Cultural Romanization]]). |

Each time Rome conquered new lands, the territory would be sectioned off into one or more [[Roman provinces|provinces]], under the administration of a [[Roman governor]], chosen annually by the Senate. He would be awarded a [[Promagistrate|promagisterial]] rank, either [[proconsul]]ar or [[propraetor]]ial, depending on the size and importance of the province (see [[Roman provinces]] for list of governor's ranks). In the later Republic, newly acquired land was often partly used to settle the discharged veterans of the military campaign who had earned their "land grant". This not only "paid off" the army, but had the added benefit of settling Roman people, with Roman customs, bringing Roman culture to newly conquered people: a form of "cultural imperialism" as well as a military one (See: [[Romanization (cultural)|Cultural Romanization]]). |

||

one of the most valued part of the military was the hoplites, who gathered to form a certain formation that allowed them to attack the enemy from far range with their 9 ft spears, yet be protected by the tightly packed shields that protected them. the only way to really defeat a hoplite formation was to "flank" it with a cavalier formation from the side where it is not protected. |

|||

== Culture of republican Rome == |

== Culture of republican Rome == |

||

| Line 182: | Line 180: | ||

==== The Second Punic War (218 to 202 BC) ==== |

==== The Second Punic War (218 to 202 BC) ==== |

||

{{Campaignbox Second Punic War}} |

{{Campaignbox Second Punic War}} |

||

Carthage spent the following years improving its finances and expanded its colonial empire in [[Hispania]] (modern Spain), |

Carthage spent the following years improving its finances and expanded its colonial empire in [[Hispania]] (modern Spain), under the [[Barcid]] family, while Rome's attention was mostly concentrated on the [[Illyrian Wars]]. However, the Barcid family had not forgotten the defeats of the first Punic war, and its most famous member [[Hannibal Barca]], swore a sacred oath never to be a friend to Rome. In [[221 BC]] Hannibal attacked [[Saguntum]] in Spain, a city allied to Rome, beginning the [[Second Punic War]]. |

||

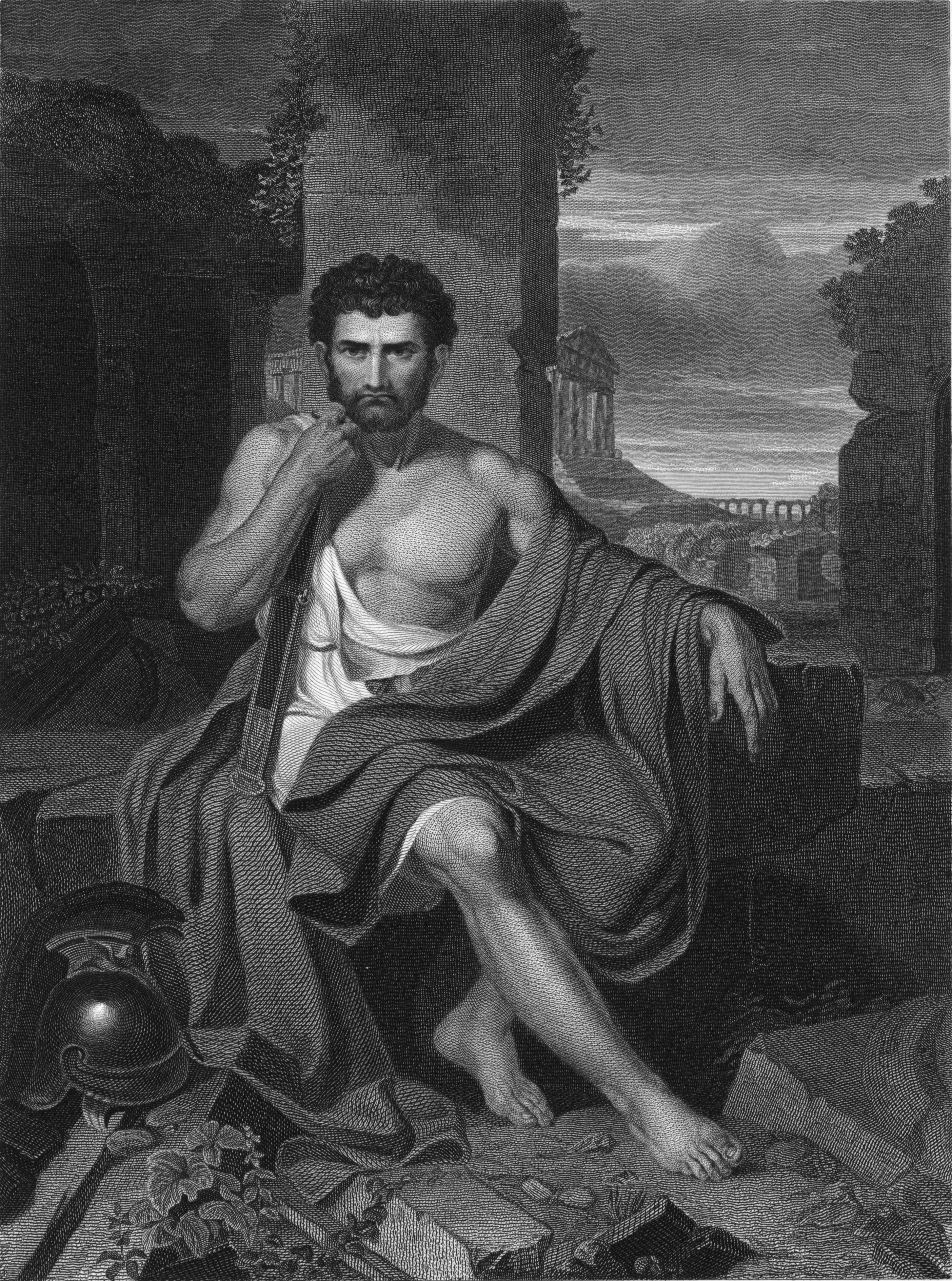

[[Image:HannibalFrescoCapitolinec1510.jpg|thumb|305px|right|Hannibal's feat in crossing the Alps with war elephants passed into European legend: a fresco detail, ''ca.'' [[1510]], [[Capitoline Museums]], [[Rome]]]] |

[[Image:HannibalFrescoCapitolinec1510.jpg|thumb|305px|right|Hannibal's feat in crossing the Alps with war elephants passed into European legend: a fresco detail, ''ca.'' [[1510]], [[Capitoline Museums]], [[Rome]]]] |

||

Hannibal was a master strategist who knew that the Roman cavalry was, as a rule, weak and vulnerable and therefore enlisted superior Numidian light cavalry along with Gallic and Hispanic heavy cavalry into his armies, with devastating effect on the Roman legions. |

Hannibal was a master strategist who knew that the Roman cavalry was, as a rule, weak and vulnerable and therefore enlisted superior Numidian light cavalry along with Gallic and Hispanic heavy cavalry into his armies, with devastating effect on the Roman legions. |

||

| Line 200: | Line 198: | ||

In Spain, a young Roman commander, [[Scipio Africanus|Publius Cornelius Scipio]] (later to be given the [[cognomen]] ''[[Africanus]]'' because of his feats during this war), eventually defeated the Carthaginian forces under Hasdrubal. Abandoning Spain, Hasdrubal attempted to bring his mercenary army into Italy to reinforce Hannibal, but was utterly defeated and killed at the decisive [[Battle of the Metaurus]] before he could do so. Scipio captured the local Carthaginian cities, made several alliances with local rulers, and then invaded Africa itself. |

In Spain, a young Roman commander, [[Scipio Africanus|Publius Cornelius Scipio]] (later to be given the [[cognomen]] ''[[Africanus]]'' because of his feats during this war), eventually defeated the Carthaginian forces under Hasdrubal. Abandoning Spain, Hasdrubal attempted to bring his mercenary army into Italy to reinforce Hannibal, but was utterly defeated and killed at the decisive [[Battle of the Metaurus]] before he could do so. Scipio captured the local Carthaginian cities, made several alliances with local rulers, and then invaded Africa itself. |

||

With Carthage now directly threatened, Hannibal returned to Africa to face Scipio, but at the final [[Battle of Zama]] in [[202 BC]] the Romans finally defeated Hannibal. Carthage sued for peace, and Rome agreed, first stripping Carthage of its foreign colonies, forcing it to pay a huge indemnity, and forbidding it to own either an army or a significant navy again. |

With Carthage now directly threatened, Hannibal returned to Africa to face Scipio, but at the final [[Battle of Zama]] in [[202 BC]] the Romans finally defeated Hannibal. Carthage sued for peace, and Rome agreed, first stripping Carthage of its foreign colonies, forcing it to pay a huge indemnity, and forbidding it to own either an army or a significant navy again. Hannibal took a leadership role in rebuilding Carthage, and succeeded so well that his envious rivals and a vengeful Rome forced him to flee to [[Asia Minor]] in [[195 BC]], where he served several local kings as a military adviser until he committed suicide in [[183 BC]] to avoid his capture by Roman agents. |

||

==== The Third Punic War (149 BC to 146 BC) ==== |

==== The Third Punic War (149 BC to 146 BC) ==== |

||

Revision as of 04:34, 27 April 2006

Template:Roman Republic infobox

- See also Roman Republic (18th century) and Roman Republic (19th century).

The Roman Republic was a phase of the ancient Roman civilization characterized by a republican form of government. The republican period began with the overthrow of the Monarchy in 510 BC and lasted until its subversion, through a series of civil wars, into the Roman Empire. The precise date in which the Roman Republic changed into the Roman Empire is a matter of interpretation, with the dates of Julius Caesar's appointment as perpetual dictator (44 BC), the Battle of Actium (September 2, 31 BC), and the date which the Roman Senate granted Octavian the title "Augustus" (January 16, 27 BC), being some of the common choices.

This is a distinction chiefly made by modern historians and not by the Romans of the time, however. The early Julio-Claudian emperors maintained that the res publica still existed under the protection of their extraordinary powers and would eventually return to its republican form.

Location

The city of Rome itself stands on the banks of the river Tiber, very near the west coast of Italy. It marked the border between the regions of Latium (the territory in which the Latin language and culture was dominant) to the south, and Etruria (the territory in which the Etruscan language and culture was dominant) to the north.

The Roman republic would expand outwards from this single city state. Eventually it would include all of the Italian peninsula, large parts of Gaul and Hispania, much of the Greek peninsula, parts of the Balkans, coastal regions of Asia Minor, part of the north African coastline, Corsica, Sardina, and Sicily.

The structure of republican Rome

The people

Like much of early Rome, the ethnic origins of the Roman people are unclear. Existing on the border of Latium and Etruria, it is debated whether the Romans were originally an ancient Italic people from the Latin region who were influenced (some say conquered at one point) by the Etruscans, or Etruscans with Italic influence. Either way, it seems likely that the Romans were heavily influenced by both cultures, and incorporated aspects from both cultures.

The inhabitants

The Roman Republic had many different classes of people who existed within the state. Each one of them had differing rights, responsibilities, and status under Roman law.

Full citizens of Rome were invariably free, property owning, men. The citizens of Rome and their families were divided into two orders or classes, known as the Patricians and Plebeians. These two social classes were hereditary, based on one's ancestry. In the early Republic, patricians monopolized all political offices and probably most of the wealth, but there are signs of wealthy and influential plebeians in the later republican records. Likewise, many patrician families lost both wealth and political influence in the later Republic. By the 2nd century BC the distinction was primarily only a religious one, as many of the priesthoods were reserved only for patricians.

The rights of Roman women varied widely throughout the history of the Republic. However, they were never accorded all the rights of citizens; they were not allowed to vote, or stand for public office, although they did have the right to own property.

Roman society also contained large numbers of slaves, who had no rights whatsoever under the law. They were considered property and could be treated however their owner wished. The death of a slave was a matter of property rather than a crime against a human being. Despite this, a freed slave, a freedman, was granted a form of full Roman citizenship, although neither they nor their descendants for three generations, could stand for any public office[1].

Roman citizenship was also used as a tool of foreign policy and control. Colonies and political allies would be granted a "minor" form of Roman citizenship, there being several graduated levels of citizenship and legal rights (the Latin Right was one of them). The promise of improved standing within the Roman "sphere of influence", and the rivalry for standing with one's neighbours, kept the focus of many of Rome's neighbours and allies centered on the status quo of Roman culture, rather than trying to subvert or overthrow Rome's influence.

The government

|

|---|

| Periods |

|

| Constitution |

| Political institutions |

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Public law |

| Senatus consultum ultimum |

| Titles and honours |

Roman republican government was a complex system, which seems to have had several redundancies within it, and was based on custom and tradition, as much as it was on law.

The Assemblies and Magistrates

The basis of republican government, at least in theory, was the division of responsibilities between various assemblies, whose members (or blocks of members) would vote on issues placed before their assembly. These assemblies included the Curiate Assembly, the Centuriate Assembly, the Tribal Assembly, the Plebeian Assembly, and the Roman Senate. Membership in such assemblies was limited by such factors as class, order, family, and income.

Several of these assemblies had specific and specialized functions, such as the Curiate Assembly which conferred Imperium on the Roman magistrates. However, two of these assemblies dominated the political life of the Republic: the Plebeian Assembly, and the Roman Senate.

Within the various assemblies, there were a number of magistratus - magistrates, which performed specialized functions.

The Romans observed two principles for their magistrates: annuality, the observation of a one-year term, and collegiality, the holding of the same office by at least two men at the same time. The supreme office of Consul, for instance, was always held by two men together, each of whom exercised a power of mutual veto over any actions by the other consul. If the entire Roman army took the field, it was always under the command of the two consuls who alternated days of command. Many offices were held by more than two men; in the late Republic there were 8 praetors a year and 20 quaestors.

The office of dictator was an exception to annuality and collegiality, and the offices of Censors to annuality. In times of military emergency a single dictator was chosen for a term of 6 months to have sole command of the Roman state. On a regular, but not annual basis two censors were elected: every five years for a term of 18 months.

Roman law and its "constitution"

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The "evolution" of Republican government

During the early and middle Republic, the Roman Senate, highest in prestige and being composed of the aristocratic, rich, and politically influential (it contained many ex-magistrates), predominated the state.

During the latter years of the Republic, a division developed within the Senate with two factions arising: the Optimates and the Populares. The Optimates held to the traditional forms of Roman government, while the Populares were those who used the fact that the Plebeian Assembly was capable of passing binding laws (plebiscites) on the Republic, to pursue political influence outside the Senate. Since the Senate controlled the finances of the state, this would lead to conflicts between the Senate and the Plebeian Assembly. Many ambitious politicians would use these conflicts to further their political career, advancing themselves as champions either of "Roman tradition", or of "The People".

The military

The Roman legion formed the backbone of Roman military power. Rome used its legions to expand its borders to eventually dominate most of Europe and the area around of the Mediterranean Sea.

The Roman Legion was one of the first modernized armies. It was a standardized, organized, disciplined military machine, in which the heroics and bravery of individuals were secondary to the function of the army as a whole. Equipment, tactics, organization, and military law was standardized and uniformly implemented. Procedures for everything from training and marching to camp building were laid out specifically, tasks allocated, and each unit and man knew his role and responsibilities within the army as a whole.

The early republic had no standing army. Instead, legions would be conscripted as needed (the term Legion comes from the Latin term Legio - "muster" or "levy"), put into the field to fight the war for which they had been created, and would then disband back to their civilan lives. Troops would be levied from Rome and her surrounding colonies, each which would be responsible for providing a particular number of soldiers. Such conscripts were theoretically taken only from those men who were property/land holders wealthy enough to equip themselves, although in time of dire military need this requirement was overlooked. This made the Roman Legion less expensive to the state, and ensured that the Legions were fighting to preserve their own property and way of life as much as trying to protect "the state".

In the later republic Gaius Marius would institute the Marian reforms which would completely alter the form of the Legion. Not only were the structure and tactics of the Roman military updated, but it was transformed into a standing army, composed mostly of lower-class "career soldiers", who would enlist for a period of 20 years, and be rewarded (traditionally, but not legally guaranteed) with a "land grant" at the end of their term of service. This had the subtle, but important, effect of refocusing the loyalty of the legionnaire who now fought as much for his General and his "pension" as for "the state".

Each time Rome conquered new lands, the territory would be sectioned off into one or more provinces, under the administration of a Roman governor, chosen annually by the Senate. He would be awarded a promagisterial rank, either proconsular or propraetorial, depending on the size and importance of the province (see Roman provinces for list of governor's ranks). In the later Republic, newly acquired land was often partly used to settle the discharged veterans of the military campaign who had earned their "land grant". This not only "paid off" the army, but had the added benefit of settling Roman people, with Roman customs, bringing Roman culture to newly conquered people: a form of "cultural imperialism" as well as a military one (See: Cultural Romanization).

Culture of republican Rome

Greek influence on Rome

It is likely that the Romans first came in contact with Greek civilization through the Greek city-states in southern Italy and in Sicily (both of which formed "Magna Graecia" - "Greater Greece"). These colonies had been established as a result of Greek expansion that took place in these two areas during the classical age of Greece, which began at approximately 479 BC. There is a remarkable commonality between the world of classical Athens and the classical world of Magna Gracia. As proof of this, one need look no further than the Greek temples in Akragas and Silinus in Sicily and the Parthenon of Athens to see that they partake of the same style of architecture at virtually the same level of architectural refinement. Thucydides documents the substantical political and military contacts that the Greek city-states of Sicily had with the Sparta and Athens during the Peloponesian War, and how the Syracusans allied with Sparta were able to defeat the military forces of Athens as they laid siege to Syracuse.

This, inasmuch as trading, as well as the mere day to day interaction between peoples of different cultures, provided opportunities for the Romans to gain exposure to Greek culture, literature, architecture, political and philosophical ideas, religious beliefs and traditions. There was a great sharing of ideas and culture among the peoples of the Mediterranean Sea while Rome was developing into the dominant power in the area.

The Latin alphabet was certainly influenced by the Greek alphabet, and the Latin language itself contains many words of Greek origin. Likewise, it is clear that Virgil was inspired by the works of Homer in his epic poem, the Aeneid. It was not uncommon for wealthy Romans to send their sons to Greece for the purpose of study, most notably in Athens. This Roman passion of Hellenic culture would increase over time.

Greek and Latin became the lingua franca of the eastern half of the Meditteranean area.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The role of culture in Rome

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The priesthood: religion in republican Rome

See also: Roman religion

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Roman legends

Few sources of Rome have survived which were written before the last decades of the Republic, and none of those is complete. By that time, the Romans retold a lengthy and complex sequence of stories about their own history, which were clearly intended as models of Roman character, good and bad, and examples for living Romans. Unfortunately, there is little evidence for early Roman history aside from this cycle, and strong reasons to believe that many of the stories did not actually happen as they are told. Many of them are borrowed from pre-existing Greek stories; some of them are plainly family stories in praise of great Roman families; some of them are aetiologies of Roman instutions which were not invented in Rome, but were common to a much larger area.

Founding of the City

According to Roman mythology, after the end of the Trojan war, the Trojan prince Aeneas sailed across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy and founded the city of Lavinium. His son Iulus later founded the city of Alba Longa, and from Alba Longa's royal family came the twins Romulus and Remus (supposedly sons of the god Mars by Rhea Silvia), who went on to found the city of Rome on April 21, 753 BC. Thus the Romans traced their origins back to the Hellenic world.

Overthrow of the kings

Livy's version of the establishment of the Republic states that the last of the Kings of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus ("Tarquin the proud") had a thoroughly unpleasant son, Sextus Tarquinius, who raped a Roman noblewoman named Lucretia. Lucretia compelled her family to take action by gathering her kinsmen, telling them what happened, and then killing herself. They were compelled to avenge her, and led an uprising that expelled the royal house, the Tarquins, out of Rome into refuge in Etruria.

Lucretia's widowed husband Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus and her brother Lucius Junius Brutus were elected as the first two consuls of the new Republic (Marcus Junius Brutus who later assassinated Gaius Julius Caesar claimed descent from this first Brutus).

History of the Roman Republic

The origins and early history of Rome are very uncertain. While there are quite specific accounts of Rome's origins and early history, these tend to be of a more mythological nature, and do not stand up as objective history when subjected to modern analysis. There even have been archeological findings in the city of Rome that predate the mythological founding date; on the other hand, the traces of actual settlement do not go back as far as that date. However, Roman origin myths probably do contain aspects of the truth, and were responsible for shaping the Romans' views of themselves.

The founding of the city

The tradition supplies several different dates for the founding of Rome, of which the most well-known is that given by the Roman historian and chronographer M. Terentius Varro: 753 BC, but this depends on the extremely doubtful traditional chronology of the Roman kings.

The actual human settlement of Rome is debatable. Rome was probably uninhabitable much before 1000 BC. There are some archaeological finds older than Varro's date; but the earliest traces of continuous settlement are usually dated to the early 600's BC.

The Monarchy (Sixth century BC)

In the beginning, Rome had kings. The tradition portrays these kings more as culture heroes than as historical figures, each of them being credited with devising some aspect of Roman culture; for example, Numa Pompilius devised Roman religion, and Ancus Martius the arts of war. It also gives most of them reigns of about forty years, which probably owes more to numerology than to history. Other details have been seen as origin stories of various Roman noble houses.

There is, however, general agreement that Rome did have a series of monarchs (some of whom were of Etruscan origin; the influence of the Etruscans can still be seen on early Roman art and architecture) and that these kings were displaced by the Roman aristocracy sometime around 500-450 BC.

The establishment of the Republic

The traditional date of the revolution against the kings is 509 BC; for the story see Overthrow of the kings above. This is again open to doubt; the arrangement of the consular fasti which support this date squeezes six consuls into the first year of the Republic, and has long stretches without any consuls at all. It is possible that, as a matter of national pride, Roman historians altered the chronology of the early republic to make it appear that Rome freed itself before Cleisthenes brought freedom to Athens. It is also suspected that later powerful families "inserted" consular ancestors into the list to support the political position of their families, pushing the founding date of the republic back in time.

The early consuls took over the roles of the king with the exception of his high priesthood in the worship of Jupiter Optimus Maximus at the sacred temple on the Capitoline Hill. For that duty the Romans elected a Rex sacrorum - a "king of holy things". It is interesting to note that the Roman Rex Sacrorum was forbidden membership in the Senate; one could not be a Senator and a Rex Sacrorum at the same time. Republican Rome distanced even this vestigial "king" from any possibility of power. Until the end of the Republic, the accusation that a powerful man wanted to make himself "Rex" - "King" remained a career-shaking charge (Julius Caesar's assassins claimed that they were preserving Rome from the re-establishment of a monarchy).

The conflict of the Orders

The relationship between the plebeians and the patricians sometimes came under such strain that the plebeians would secede from the city, taking their families and movable possessions, and set up camp on a hill outside the walls. Their refusal to cooperate any longer with the patricians led to social changes. Only about 15 years after the establishment of the Republic in 494 BC, plebeians seceded and chose two leaders to whom they gave the title Tribunes. The plebeians took an oath that they would hold their leaders 'sacrosanct' - 'untouchable' during their terms of office, and that a united plebs would kill anyone who harmed a tribune. The second secession in 471 BC led to further legal definition of their rights and duties and increased the number of tribunes to 10. The final secession ended in 287 BC and the resulting Lex Hortensia gave the vote of the Concilium Plebis or "Council of the Plebeians" the force of law. It is important to note that this force of law was binding for both patricians and plebeians, and in fact made the Council of the Plebeians a leading body for approving Roman laws.

Roman expansion into Italy (340 to 268 BC)

Throughout the 4th century BC the Romans fought a series of wars with their neighbors, most notably the Sabines and the Samnites, who were their main rivals on the Italian mainland. Eventually, Rome came to dominate the Latin League, a coalition of city-states in the area of Latium, eventually dissolving the league and placing the territory under hegemonic control at the end of the Latin War.

During this era, Rome, and others of the Latin League, clashed with foreign powers as well, and not always successfully. In 390 BC the Gauls from Gallia Cisalpina (modern Po Valley) under the leadership of Brennus, defeated the Roman legions and sacked Rome itself, requiring a huge ransom to avoid completely destroying the city (A Roman senator protested that the weights used to measure the ransom of gold were inaccurate. In response, Brennus threw his sword onto the weights and uttered the famous words: "Vae Victis" - "Woe to the vanquished").

In 283 BC Pyrrhus of Epirus arrived to aid the Greek colony of Tarentum against the Romans. Pyrrhus was widely considered the greatest military leader since Alexander the Great, but even after winning three battles he was unable to defeat the Roman Republic, taking great losses as he did so. Pyrrhus is said to have uttered the phrase: "Another such victory and I shall be lost" coining the term "Pyrrhic victory". Pyrrhus withdrew to fight wars in Sicily and Greece, giving the Romans international military prestige, and bringing them to the attention of the Hellenistic superpowers of the East.

Through its colonies, and allied city-states, Rome had a vast amount of manpower to draw upon, which it used as a recruitment pool for its Legions. This gave it the ability to simply raise legion after legion, continuing to fight where other nations may simply have capitulated. Rome also demonstrated an unwillingness to be, or to stay, beaten. This characteristic determinism was shown in such later engagements such as First Punic War where the Roman military, faced with a 70% loss of its fleet due to storms, managed to rebuild the entire fleet in a mere two months.

Another unique characteristic of the Republic was its treatment of conquered people. Those conquered by Rome were brought under the "protection" of Rome; they were granted a form of citizenship, and had specific rights under Roman law. They were also held to certain obligations as well, most notably the requirement to provide troops for the Legions. This had a two-fold effect. First, Rome had a large pool of manpower to draw its Legions from (the entire Latin League). This allowed it to simply field army after army, refusing to be defeated. Secondly, by having several levels of citizenship and rights under Roman law, the attention of conquered people was focused on improving their rights within the Roman law, and in competing with rival client-states for status within the Roman sphere of influence, rather than trying to rid themselves of Roman dominance. This policy of "divide and rule" made conquered people willing participants in their own submission to Roman law.

By 268 BC the Romans dominated most of Italy through a network of allies, conquered city-states, colonies, and strategic garrisons. At that time Rome started to look beyond Italy, towards the islands and the rich trade of the Mediterranean Sea.

Conquest of the West: The Punic Wars

In 264 BC, Carthage was a Phoenician colony on the coast of modern Tunisia. It was a powerful city-state with a large commercial empire, and, with the exception of Rome, the strongest power in the western Mediterranean. While Carthage's navies were uncontested, it did not maintain a strong standing army. Instead, it relied on mercenaries, hired with its considerable wealth, to fight its wars for it.

As soon as Rome had consolidated its control in Italy, it came into conflict with Carthage as Rome attempted to expand its influence into the Mediterranean. Rome and Carthage would fight a series of three Punic Wars ('Punic' is Latin for 'Phoenician') between 264 and 146 BC. The Roman victories over Carthage in these wars made Rome the most powerful nation in Europe and the Mediterranean, a status it would retain until the division of the Roman Empire into the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire by Diocletian in 286 AD.

The First Punic War (264 to 241 BC)

The First Punic War between Rome and Carthage began as a local conflict in Sicily between Hiero II of Syracuse, and the Mamertines of Messina. The Mamertines had the bad judgement to enlist the aid of the Carthaginian navy, and then betray the Carthaginians by entreating the Roman Senate for aid against Carthage. The Romans sent a garrison to secure Messina, and the outraged Carthaginians then lent aid to Syracuse. With the two local powers now embroiled in a local conflict, local tensions quickly escalated into a full-scale war between Carthage and Rome for the control of Sicily.

The first Punic war was mostly a naval war. After a sound defeat at the land battle of Agrigentum, the Carthaginian leadership resolved to avoid direct land-based engagements with the Roman legions, and concentrated on the sea.

Initially, an experienced Carthaginian navy prevailed against an amateur Roman Navy (see: Battle of the Lipari Islands). Rome responded by drastically expanding its navy (there is some dispute whether or not it did so by copying storm-beached and captured Carthaginian warships): within two months the Romans had a fleet of over 100 warships. Because they knew that they could not outsail the Carthaginians, the Romans added an "assault bridge" to Roman ships, known as corvus - the "Raven". This bridge would latch onto enemy vessels, bring them to a standstill, and allow Roman legionaries to board and capture Carthaginian ships with ease. This tactic stripped the Carthaginian navy of its advantage (superiority in ship-to-ship engagement), and allowed Rome's superior infantry to be brought to bear in naval conflicts. However, the corvus was also cumbersome and dangerous, and was eventually phased out as the Roman navy became more experienced and tactically proficient.

Save for the disastrous defeat at the battle of Tunis in Africa, and the naval engaments of Lipari Islands and Drepana, the first Punic war was mostly an unbroken string of Roman victories. In 241 BC, Carthage signed a peace treaty giving Rome the total control of Sicily.

In 238 BC the mercenary troops of Carthage revolted (see Mercenary War) and Rome took the opportunity to seize the islands of Corsica and Sardinia away from Carthage as well. From that point on, the Romans used the term "Mare Nostrum" - "our sea" and effectively controlled the Mediterranean. Rome's navies could prevent amphibious invasion upon Italy, control the important and rich sea trade routes, and invade other shores.

The Second Punic War (218 to 202 BC)

Carthage spent the following years improving its finances and expanded its colonial empire in Hispania (modern Spain), under the Barcid family, while Rome's attention was mostly concentrated on the Illyrian Wars. However, the Barcid family had not forgotten the defeats of the first Punic war, and its most famous member Hannibal Barca, swore a sacred oath never to be a friend to Rome. In 221 BC Hannibal attacked Saguntum in Spain, a city allied to Rome, beginning the Second Punic War.

Hannibal was a master strategist who knew that the Roman cavalry was, as a rule, weak and vulnerable and therefore enlisted superior Numidian light cavalry along with Gallic and Hispanic heavy cavalry into his armies, with devastating effect on the Roman legions.

There were three major military theaters in this war: Italy, where Hannibal defeated the Roman legions repeatedly; Spain, where Hasdrubal Barca, a younger brother of Hannibal, defended the Carthaginian colonial cities with mixed success until eventually retreating into Italy; and Sicily where the Romans held military supremacy.

After assaulting Saguntum, Hannibal surprised the Romans, by directly invading Italy, leading a large army of mercenaries composed mainly of Gauls, Hispanics, Numidians, and most famously a dozen African war elephants, through the Alps. Hannibal's forces defeated the Roman legions in several major engagements, most famously at the Battle of Cannae, but his long-term strategy failed. Lacking siege engines and sufficient numbers to take the city of Rome itself, he had planned to turn the Italian allies against Rome and starve the city out. However, with the exception of a few of the southern city-states, the majority of the Roman allies remained loyal and continued to fight alongside Rome, despite Hannibal's near-invincible army devastating the Italian countryside.

More importantly, Hannibal never received any significant reinforcements from Carthage, despite his many pleas. This lack of reinforcements prevented Hannibal from decisively ending the conflict by conquering Rome through force of arms.

Rome, on the other hand, was also incapable of bringing the conflict in the Italian theater to a decisive close. Not only were they contending with Hannibal in Italy, and his brother in Spain, but Rome had embroiled itself in yet another foreign war, and was fighting the first of its Macedonian wars at the same time.

With Hannibal lacking decisive force from Carthage, and the Roman military spread over three separate theatres of conflict, Hannibal's Italian war carried on inconclusively for sixteen years.

In Spain, a young Roman commander, Publius Cornelius Scipio (later to be given the cognomen Africanus because of his feats during this war), eventually defeated the Carthaginian forces under Hasdrubal. Abandoning Spain, Hasdrubal attempted to bring his mercenary army into Italy to reinforce Hannibal, but was utterly defeated and killed at the decisive Battle of the Metaurus before he could do so. Scipio captured the local Carthaginian cities, made several alliances with local rulers, and then invaded Africa itself.

With Carthage now directly threatened, Hannibal returned to Africa to face Scipio, but at the final Battle of Zama in 202 BC the Romans finally defeated Hannibal. Carthage sued for peace, and Rome agreed, first stripping Carthage of its foreign colonies, forcing it to pay a huge indemnity, and forbidding it to own either an army or a significant navy again. Hannibal took a leadership role in rebuilding Carthage, and succeeded so well that his envious rivals and a vengeful Rome forced him to flee to Asia Minor in 195 BC, where he served several local kings as a military adviser until he committed suicide in 183 BC to avoid his capture by Roman agents.

The Third Punic War (149 BC to 146 BC)

Rome now concentrated its attention on its ongoing Macedonian wars, and into pacifying its newly acquired territory in Hispania.

Carthage, however, was reduced to a single city-state, with no military, under huge financial debt, and dependent on Rome for military protection and arbitration of international matters. With no military, Carthage suffered raids from its neighbour Numidia, and under the terms of the Roman treaty, such disputes were arbitrated by the Roman Senate. As Numidia was a favored "client state" of Rome, Roman rulings were slanted heavily in Numidian favor.

After some fifty years of this condition, Carthage managed to discharge its war indemnity, and considered itself no longer bound by the restrictions of the treaty, although Rome believed otherwise. It mustered an army to repel Numidian forces, and immediately lost a war with Numidia, placing themselves in further debt, this time to Numidia.

This new-found Punic militarism alarmed many Romans, including Cato the Elder who after a voyage to Carthage, ended all his speeches by saying: "Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam." - "I also think that Carthage must be destroyed".

In 149 BC, in an attempt to pacify Carthage, Rome made a series of escalating demands, ending with the near-impossible demand that the city be demolished and re-built away from the coast, deeper into Africa. The Carthaginians refused this last demand and Rome declared the Third Punic War. Scipio Aemilianus besieged the city for three years before he breached the walls, sacked the city, and burned Carthage to the ground. According to legend, the Romans went so far as to sow salt into the earth so that nothing might ever be grown there. This is highly unlikely, considering the high price salt commanded in those times, and is most likely only a legend. The surviving Carthaginians were sold into slavery, and Carthage ceased to exist, until Octavian would rebuild the city as a Roman veterans' colony, over a century later.

Conquest of the East: the Macedonian and Seleucid wars

The Macedonian and Seleucid wars were a series of conflicts fought by Rome during and after the second Punic war, in the eastern Mediterranean, the Adriatic, and the Aegean. Along with the Punic wars, they resulted in Roman control or influence over the entire Mediterranean basin.

The first Macedonian war (215 to 202 BC)

During the Second Punic War, Philip V of Macedon allied himself with Hannibal. Fearing possible reinforcement of Hannibal by Macedon, Rome dispatched forces across the Adriatic. Roman legions (aided by allies from the Aetolian League and Pergamon after 211 BC) did little more than skirmish with Macedonian forces and seize minor territory along the Adriatic coastline in order to "combat piracy". Rome's interest was not in conquest, but in keeping Macedon, the Greek city-states, and political leagues carefully divided and non-threatening. The war ended indecisively in 202 BC with the Treaty of Phoenice. While a minor conflict, it opened the way for Roman military intervention in Greece.

The second Macedonian war (200 to 196 BC)

In 201 BC, ambassadors from Pergamon and Rhodes brought evidence before the Roman Senate that Philip V of Macedon and Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire had signed a non-aggression pact. Although some scholars view this "secret treaty" as a fabrication by Pergamon and Rhodes, it resulted in Rome launching the second Macedonian war, with aid from its Greek allies. It was an indecisive conflict until the Roman victory at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC. After Rome imposed the Treaty of Tempea, Philip V was forbidden to interfere with affairs outside his borders, a condition he adhered to for the rest of his life. In 194 BC Rome declared Greece "free", and withdrew completely from the Balkans. It seemed that Rome had no further interest in the region.

The Seleucid War (192 to 188 BC)

Following the second Macedonian war, the Aetolian League was unhappy with the amount of territory ceded to them by Rome as "reward" for their aid. In response, they "invited" Antiochus III of Seleucid Syria to assist them in freeing Greece from "Roman oppression". Antiochus sent a small force into Greece in 192 BC, and Rome responded by sending its legions back into Greece, driving out the Seleucids.

Possibly partly because Antiochus had given Hannibal shelter as his military advisor (Hannibal had urged the king not to enter Greece with so few troops and been ignored), Rome sent a force of 30,000 troops under Scipio Africanus into Asia Minor. Roman victories at Thermopylae (191 BC) and the Battle of Magnesia (190 BC), forced Antiochus to sign the Treaty of Apamia (188 BC), ceding Seleucid territory to Rome and Pergamon, and extracting a war indemnity of 15,000 talents of silver.

The third Macedonian War (172 to 168 BC)

Upon Philip's death in Macedon (179 BC), his son, Perseus of Macedon, attempted to restore Macedon's international influence, and moved aggressively against his neighbors. When Perseus was implicated in an assassination plot against an ally of Rome, the Senate declared the third Macedonian War. Initially, Rome did not fare well against the Macedonian forces, but in 168 BC, Roman legions smashed the Macedonian phalanx at the Battle of Pydna. Perseus was later captured and the kingdom of Macedon divided into four puppet republics.

The fourth Macedonian War (150 to 148 BC)

For several years Greece was peaceful, until a popular uprising in Macedon rose up under Andriscus, who claimed to be a son of Perseus. Rome once again dispatched its legions into Greece, and put down the rebellion. This time, Rome did not withdraw from the region, forming the Roman provinces of Achaea, Epirus and Macedonia, establishing a permanent Roman foothold on the Greek peninsula.

In response, the remaining free Greek powers of the Achaean League, rose up against Roman presence in Greece. The League was swiftly defeated, and, as an object lesson, Rome utterly destroyed the ancient city of Corinth in 146 BC, the same year that Carthage was destroyed.

The Macedonian wars had come to an end, along with Greek independence.

The acquisition of Asia

In 133 BC, a dying King Attalus III of Pergamon willed his entire kingdom to the Roman Republic to avoid dynastic disputes amongst his heirs, and to avoid the possibility that Rome would take the opportunity to seize Pergamon by force. Events were complicated by the rebellion of Aristonicus, a relative of Attalus III who was proclaimed king of Pergamon with the title of Eumenes III. After four years of war (133–129 BC) he was defeated and captured by Rome. Pergamon was reorganized into the foundation of the province of Asia, and became one of the most wealthy provinces the Romans ever controlled. Because of the vast wealth of Asia, the province attracted the corrupt and greedy among the Senate, and its Governors were notorious for nearly a century after its acquisition.

This sudden windfall had unforeseen, and perhaps unfortunate, consequences for the political situation in Rome, and the political reform movement of the Gracchi.

The beginning of the end

Economic and Political strife in Rome

Rome's military and diplomatic successes around the Mediterranean resulted in unforeseen economic and political pressures on the state. While factional strife had always been part of Roman political life, the stakes were now far higher; a corrupt provincial governor could acquire unbelievable wealth; a successful military commander needed only the support of his legions to rule vast territories.

Starting with the Punic Wars, the Roman economy began to change, concentrating wealth in the hands of a few powerful clans and causing political tension within Rome.

Much of the newly conquered territories were seized by rich and powerful families. Additionally, as only men who could provide their own arms were eligible to serve in the Legions, the majority of Roman troops came from the middle class land holders who theoretically would be fighting to defend their own lands. With military campaigns now lasting years rather than just a few months, soldiers could not return to work their farms. With their holdings lying fallow, their families quickly fell into debt, and their lands were lost to debtors - typically wealthy landholders who consolidated these properties into vast latifundia. Formerly middle-class soldiers would return from years of campaigning to find themselves landless, unable to support their families, and ironically, unemployable because the successes of the Legions made slaves a much cheaper source of labor.

By 133 BC the economic imbalance was too acute to ignore, but the wealthy patricians and old families in the Senate had a vested interest in preserving the status quo. It seemed that a land reform through the traditional channels was an unlikely prospect.

The Gracchi reforms (133 to 121 BC)

In 133 BC, a tribune, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, tried to introduce land reform to redistribute "publicly held land" to the now landless returning soldiers. He proposed the enforcement of a Roman law, which had mostly been ignored, which limited the use of public lands. While "public lands" were technically state owned, such land was often used by wealthy landholders, many of them Senators. Under the enforcement of this law many of them would lose property.

As it seemed unlikely that the Senate would agree to enforce the law, Tiberius bypassed the Senate entirely, and tried to pass his reform through the Plebeian Assembly as a plebiscite, using the legal principle of Lex Hortensia. While technically legal, this was a violation of political custom, and outraged many patricians. The Senate blocked Tiberius by bribing his fellow tribune to veto the bill. Tiberius then passed a bill to depose his colleague from office, violating the principle of collegiality. With the veto withdrawn, the land reform passed. An incensed Senate refused to fund the land commission. Tiberius used the plebeian assembly to divert funds from the income of Pergamon to fund the commission, challenging Senate control of state finances and foreign policy. When it became clear that Tiberius did not have enough time to finish his land reforms, even with political and economic backing, he announced that he would run again for the tribunate, violating annuality. This was the last straw for the patricians, who, fearing that Tiberius was setting himself up as a tyrant, responded by slaughtering Tiberius and 300 of his followers in the streets of Rome.

Tiberius' younger brother Gaius Sempronius Gracchus attempted to continue political reforms using similar tactics almost ten years later. He seems to have been more of a demagogue who attempted to pass a slew of popular laws to gain popular support rather than to be a political reformer with a specific agenda like his brother. He was neither as successful, or as popular, as his elder brother, but he managed to create many political enemies. Escalating political tensions finally exploded once again in violence on the Capitoline Hill, where Gaius Gracchus and 3,000 of his followers were killed.

Whatever their intentions, the political careers of the Gracchi brothers had broken the political traditions of Rome, and introduced mob violence as a tool of Roman political life. It was a change that the Republic would not recover from.

Marius and Sulla

Gaius Marius, Military Reformer (107 to 100 BC)

Following the scandal of the Gracchi, Roman politics became a mix of traditional forms, demagoguery, and mob violence. Additionally, Rome was finding the military demands of its holdings extremely taxing.

A badly executed, and unpopular, Jugurthine War (112-105 BC) was dragging on in Numidia. It would launch the career of Gaius Marius, and bring about fundamental changes in the Republic.

Marius was a "novus homo" from Arpinum who had wealth and minor political influence, but who was not a member of the Roman aristocracy. After serving as a minor officer in the Jugurthine War, Marius returned to Rome, and stood for election as Consul in 107 BC, based on the promise to end the war within a year. Surprisingly, Marius was elected.

Upon attaining the Consulship, and over the extreme protests of the Senate, Marius instituted the Marian reforms in 107 BC. These reorganized the tactical structure of the Roman legion, and allowed the recruitment of poor and landless Roman citizens into the legions, at state expense. Soldiers would enlist for a period of 20 years, and would be rewarded with a land grant at the end of their term of service. This would change the nature of the legions, as legionnaires would from this point on be professional soldiers fighting for their "pension", and the general who would obtain it for them, as much as for "the state".

With his new "head count" armies, Marius returned to Numidia as the Consular commander.

Although Marius did not complete the war within the year, he was elected Consul for a second time, and in absentia (both amazingly unusual exceptions), to complete the war. In 105 BC, Marius defeated Jugurtha, who was captured by King Bocchus I of Mauretania and handed over to one of Marius' quaestors, Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

Returning to Rome a military hero, Marius arrived to deal with the aftermath of the disaster of the Battle of Arausio in 105 BC, and the fact that Roman territory was now open to invasion from migrating Cimbri and Teutoni tribes. Amazingly, Marius was elected Consul for three more years (104 to 102 BC) to fight the remainder of the Cimbrian War.

He raised new Legions from plebeian volunteers, trained them, crushed the Teutoni at the Battle of Aquae Sextae in 102 BC, and aided Quintus Lutatius Catulus to likewise defeat the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae in 101 BC. Having saved Rome, Marius was elected to Consul an unprecedented 6th time in 100 BC.

However, Marius would prove that he was a General, and not a politician. After a humiliating political scandal concerning Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, Marius completely withdrew from public political life.

The Social war (91 to 88 BC)

With Marius' retirement, the way was cleared for the political career of Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Sulla was a patrician, and a traditional political conservative, who had served under Marius as a competent officer in Numidia and Germany. However, there was political enmity between the two, as Marius had "slighted" Sulla by failing to credit him with the capture of Jugurtha.

In 91 BC, a tribune and political champion of the rights of the Latin allies, Livius Drusus, attempted to pass a law granting full Roman citizenship to all the Italian allies living south of the Po River. When Drusus was murdered, many of the Italian allies, especially those among the Samnites, exploded into the rebellion of the Social war (Soccii is Latin for ally).

Ironically, to try and end the war, Rome offered full citizenship to any of the rebelling allies who would cease the conflict. Most of the allies ceased fighting, but several continued the rebellion. In response, Gaius Marius came out of retirement, and commanded the Roman forces in northern Italy, while Lucius Cornelius Sulla commanded the Roman legions in southern Italy, bringing the war to an end in 88 BC. Following their joint victory, Sulla stood for election as Consul, and was elected.

The first Mithridatic, and Roman civil wars (88 to 83 BC)

When Mithridates VI of Pontus overran Bithynia as the Social war ended, and slaughtered tens of thousands of Roman citizens in the Asiatic Vespers, the Senate gave Sulla the Consular command of the expeditionary force sent to extract revenge against Mithridates.

Gaius Marius did not wish to return to political obscurity, and bribed the passage of a bill through the Plebeian Assembly to give himself command of Sulla's armies. When Sulla heard of this while raising his legions in southern Italy, he turned his armies on Rome itself! Sulla's legions captured the city after protracted and bloody street fighting in Rome, and Marius was forced to flee to Africa. Sulla then departed to confront Mithridates and his allies. Marius returned to Rome with Lucius Cornelius Cinna and captured the city with his legions. Marius appointed himself Consul for a 7th time and proceeded to butcher Sulla's supporters. However, only a few weeks later Marius died of a massive brain hemorrhage. Cinna retained power, and in an almost comic twist, decided to ignore Sulla's existence completely, even sending a second army to Pontus. The two Roman armies spent as much time fighting each other as Mithridates, and the war came to a disappointing close with the Treaty of Dardanos in 85 BC.

Sulla then returned to Rome with his Legions in 83 BC.

The bloody reign of Sulla (83 to 80 BC)

Cinna was killed by his own troops trying to muster them against the returning Legions of Sulla, leaving Gnaeus Papirius Carbo and other of Marius' supporters to deal with Sulla's return. In 83 BC Sulla landed in southern Italy, and full scale Roman civil war broke out in the Italian countryside. The war raged on for a year and a half, but Sulla's legions (aided by those of a young Marcus Licinius Crassus and a young Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus) finally prevailed, taking the city of Rome at the Battle of the Colline Gate.

Sulla then instituted a bloody series of purges, subjecting his enemies to proscription: a process named for the lists of the condemned posted in the Roman forum. People were stripped of their legal rights and protection, had their (and their family's) property impounded by the state, and a bounty placed on their lives. Thousands of Romans who opposed Sulla, or even those who simply had wealth that he and his followers coveted, were butchered in this fashion over a period of two years.

Sulla also appointed himself dictator without limit, and began reorganizing the state, attempting to return power to the Senate. He strongly curtailed the power of the Plebeian Assembly, doubled the size of the Roman Senate, gave the Senate veto power over the decrees of the Plebeian Assembly, and stripped the Tribunes of much of their power.

With his reforms in place, Sulla then, surprisingly, resigned his dictatorship in 80 BC, withdrew completely from public life, and retired to his country estates — if ancient sources are correct, there to pursue a life of debauchery — until his death in 78 BC.

The First Triumvirate

Throughout the decade of the 70's, Roman politics was controlled by the conservatives, due to Sulla's reforms. These reforms would be wiped away piecemeal over the next ten years due to gradual legislative change. Sulla's tactic of using military force to seize power in Rome was the legacy that endured.

Pompey in the West: The revolts of Lepidus and Sertorius (78 to 72 BC)

Within two years of Sulla's death, someone attempted to emulate him. When one of the Consuls of 78 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, failed to carry out his intended political agenda, or have his Consulship extended, he attempted to raise an army in Cisalpine Gaul and march on Rome to seize power. The Senate turned to a military general who had aided Sulla in his civil war, and shown himself also to be a competent commander in Africa for Sulla: Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Pompey put down Lepidus's rebellion, and then marched his own legions on Rome. Pompey camped his army outside the walls of Rome, and "requested" that he be given the right to campaign against the rebellion of Quintus Sertorius in Hispania (Sertorius was an opponent of Sulla's who had fled to Hispania during the proscriptions, and set up his own "counter-Rome" in that province). Under the threat of the legions, the Senate agreed, and Pompey marched on Hispania where he would campaign for the next 6 years, gaining a great military reputation for himself.

Crassus: Spartacus and the Third Servile War (73 to 71 BC)

One of the more easily over-looked social aspect in classical antiquity and of Roman society is Slavery. At that time almost all societies used slaves in various positions. The vast majority would perform back-breaking and dangerous labor and the more educated slave (a small minority) would work in a more bureaucratic position. The lives of the majority of slaves would usually consist of hard work and their living conditions would be quite harsh. From time to time slaves would revolt and military might would be used to crush the rebellion and the matter would be conveniently forgotten and nothing would happen. This time, it would be different.

The Roman Republic would be rocked by a slave revolt led by Spartacus who according to ancient sources was a Thracian auxilia who had deserted from the Roman legions. He had been captured, enslaved and trained as a gladiator. In 73 BC he and some of his fellow gladiators rebelled at Capua and set up a military camp on Mount Vesuvius. Slaves across all the Italian peninsula flocked to him, and their numbers soon swelled to about 70,000. The best Roman legions were absent from Italy: some were in Spain under the command of Pompey, suppressing a rebellion led by Quintus Sertorius, while others were fighting in Asia Minor under the command of Lucius Licinius Lucullus against Mithridates. Initially, the rebel slaves had great success against the Roman legions sent against them, and wreaked havoc across the Italian peninsula. In 71 BC, however, Marcus Licinius Crassus was given military command and crushed the rebels. About 6,000 were crucified; 10,000 survivors who escaped were intercepted by Pompey, then returning with his army from Spain. Although Crassus did most of the fighting, Pompey also claimed credit for the victory, and this created tension between the two men.

Pompey and Crassus (70 BC)

With the slave rebellion crushed, Pompey once again marched his legions on Rome, and encamped outside its walls. He then demanded that he be elected Consul for the year 70 BC. In response Crassus immediately marched his legions towards Rome. However, instead of blocking Pompey's extortion, he camped his own legions outside Rome and demanded that he be elected co-Consul with Pompey. The Senate had no real choice but to agree.

Crassus and Pompey spent most of the year trying to outdo each other in the lavishness of their public expenditures. However they also pushed through several laws which wiped away the last vestiges of the "Sullan Reforms", and restored the problematic power of the Plebeian Assembly.

Pompey in the East: The Third Mithradatic War

Meanwhile, Lucullus was fighting quite successfully, against Mithridates and his ally and son-in-law, Tigranes the Great, King of Armenia, but was unable to completely pacify the territories he conquered. At the same time, Marcus Antonius Creticus (father of Mark Antony) and Q. Caecilius Metellus were attempting to stamp out the plague of piracy afflicting the Mediterranean, with reportedly grotesque incompetence.

Due to these lack of successes, Pompey was given an extraordinary military command in 66 BC. He stamped out piracy within forty-nine days and then began pursuing Mithridates. Pompey annihilated his army, and Mithridates remained a fugitive for the last three years of his life. Pompey followed up these successes by conquering the entirety of the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, ending the rule of the Syrian Seleucid dynasty. The captured wealth of the conquests more than doubled the income of the Roman state, and Pompey now surpassed Crassus as the wealthiest man in Rome.

The Catilinarian Conspiracies

The economic situation in Rome itself, however, was still problematic. Debt was the intractable problem and many, both noble and not, found themselves burdened with incredible debts. Their mantle was taken up by Lucius Sergius Catilina, who ran for consul in 64 BC for the year 63 BC on the platform of a wholesale debt cancellation – essentially a redistribution of wealth. Despite his noble birth, his policies scared the optimates, who instead supported the novus homo Marcus Tullius Cicero. Cicero was duly elected; Catilina finished third and out of office. Catilina ran again the following year, but this time he was defeated even more heavily. He then, along with several dissolute senators, began planning a coup d'état that would include arson throughout Rome, the arming of slaves, and the accession of Catilina as dictator. Cicero found out and informed the Senate in a series of brilliant speeches, and was given absolute power by the senate ("senatus consultum ultimum"), in order to save the republic. He ordered the execution of the conspirators in the city without due trial; and his fellow consul, Gaius Antonius Hybrida defeated the army of Catilina near Pistoria. None of Catilina's soldiers were taken alive.

Julius Caesar and the First Triumvirate

In 62 BC Pompey returned from the east. Many senators, especially among the optimates, feared that Pompey would follow in the footsteps of Sulla and establish himself as dictator. Instead, Pompey disbanded his army upon arriving in Italy. Nevertheless, the Senate maintained its opposition to land grants for Pompey's veterans and the ratification of Pompey's eastern settlement. In addition, the Senate was also stonewalling Pompey's old enemy, Crassus, in his attempts to gain some measure of relief for his allies, the tax farmers. Now arriving onto the scene was a young politician who had a heretofore successful, but not brilliant, career — Gaius Julius Caesar. Caesar took advantage of the two enemy's dissatisfaction to bring them into an informal alliance known as the First Triumvirate. In addition, he reinforced his alliance by marrying his daughter, Julia, to Pompey. The three triumvirs would be able to dominate Roman politics due to their collective influence; the first step was Caesar's election to the consulship for 59 BC.

Attempting to pass the laws which would benefit both Pompey and Crassus, Caesar ran into heavy opposition from his very conservative consular colleague Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, who used all manner of parliamentary tactics to stall the legislation. Caesar resorted to violence and Bibulus ended up under house arrest for most of the year, while Caesar was able to pass almost all of his legislation. He was then appointed Governor of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum for a five year period. When the Governor of Transalpine Gaul died unexpectedly, the Senate assigned that province to him as well. Caesar took up his governorships in 58 BC. He immediately launched a series of military campaigns across all of Gaul known as the Gallic Wars, and even raided Germania and Britannia. For a nine year period he carefully played the gallic tribes against each other (divide and rule) and crushed all military opposition. These wars caused massive death and destruction and were, technically, illegal, as Caesar had exceeded his authority (which was supposedly limited to his provinces) in launching the invasions, but in Rome no one, except his enemies in the Senate, was too concerned. Meanwhile, the Triumvirate at home needed a boosting. In 56 BC, the three triumvirs met at Lucca, just inside Caesar's province of Cisalpine Gaul (as a man in control of an army, he was not allowed to cross into Italy). The three triumvirs reached a new settlement: Crassus and Pompey were once again to be elected consuls for the year 55 BC; Pompey kept the command of the Roman legions in Spain (which he ruled in "absentia"), and Crassus, desiring military glory so that he could be on the same level as Pompey and Caesar, was given a military command in the east. Caesar's governorships were extended for another five years.

The Death of Crassus and the Dissolution of the Triumvirate

In 53 BC, Crassus launched an invasion of the Parthian Empire. He marched his army deep into the desert; but here his army was cut off deep in enemy territory, surrounded and routed at the Battle of Carrhae. Crassus himself was killed in battle, the story being that the Parthians, upon finding his body poured molten gold down his throat, symbolising Crassus' obsession with money.

The death of Crassus removed some of the balance in the Triumvirate; consequently, Caesar and Pompey began to move apart. In 52 BC, Julia died, widening the gap emerging between the two. Pompey, who previously had been the leader of the Triumvirate and, indeed, of the republic, was beginning to see his authority threatened by Caesar, whose campaigns in Gaul were vastly increasing his prestige, fortune and power. Consequently, Pompey began to align increasingly with the optimates, who themselves were very much opposed to Caesar and his "party" (i.e., the populares).

At the same time an united Gallic uprising, led by Vercingetorix, nearly succeeded in toppling the Roman military presence in Gaul; but Caesar, with his usual speed and brilliant mix of military strategy and ruthlessness, was able to defeat Vercingetorix at the siege of Alesia. The Gallic Wars were essentially over (a third of all male Gauls had been slain; another third had been sold into slavery).

By 50 BC all Gallic resistance had been stamped out and Caesar had a veteran and loyal army to further his political ambitions. With Caesar's governorship drawing to a close, the two greatest political and military leaders of the Roman Republic were hard-pressed to find any common ground, and a crisis was growing which would be the final nail in the coffin of the Republic.

The Civil War and Caesar's dictatorship

The key issue was whether or not Caesar would be able to stand for the consulship of 48 BC in absentia. Caesar's governorship's would expire at the end of 49 BC, and so would his immunity from trial. He was sure to be charged with violations of the constitution stemming from his consulship of 59 BC, which could result in his political and probably even physical, death. If he was allowed to run in absentia, he could immediately assume another consulship, and then following that, immediately assume a new governorship, always maintaining his immunity. The optimates were heavily opposed to Caesar's standing in absentia, and on the first of January, 49 BC, passed a law declaring Caesar a public enemy and demanded his return to Rome to stand trial. Pompey was given absolute authority to defend the Roman Republic. This news reached Caesar probably on January 10, and proclaiming "alea iacta est" - "the die is cast" (in fact, he said it in Greek, quoting Menander), Caesar crossed the Rubicon River (the boundary between Cisalpine Gaul and Italy) with his army. Civil war had begun again.

Caesar, leading a tough veteran army, quickly swept down the Italian peninsula, and encountered meager resistance from freshly recruited legions. The only exception was at Corfinium, where Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus was defeated. Caesar pardoned him, under his notable policy of clemency — he wanted to let everyone know that he would not be the next Sulla. He took Rome without opposition, and then marched south to try and stop Pompey, who was trying to withdraw from Brundisium across the Adriatic Sea to Greece. Caesar came close, but Pompey and his armies were able to escape at the last minute.

In 48 BC Pompey controlled the seas, and his legions heavily outnumbered Caesar's; but the legions of Caesar, after ten years of vigorous campaigns, were experienced veterans. Caesar, for his lack of a navy, solidified his control over the western Mediterranean, notably at Massilia and in Spain. Then he invaded Greece. The two leaders first faced each other at the Battle of Dyrrhachium, where Pompey won. Nevertheless, Pompey failed to follow up on his victory, and Caesar was able to regroup and win a decisive victory at the Battle of Pharsalus on the 9th of August. Pompey fled to Egypt, where he hoped to find assistance.

Caesar, pursuing Pompey, arrived in Alexandria, capital of Ptolemaic Egypt, to find the breadbasket of the Mediterranean in a state of civil war. Agents of the young king, Ptolemy XIII, had assassinated Pompey and presented his head to Caesar, believing it would please him and that he would support Ptolemy against his sister, Cleopatra. Caesar was too a cunning politician to make such a mistake. In a careful way he lamented the inglorious death of Pompey, a fellow Roman, and supported the military weaker side, whose gratitude would logically be much greater. He even began an affair with Cleopatra. A long, drawn-out city battle resulted, one of the most dangerous of Caesar's career, but he triumphed and placed Cleopatra on the throne along with another brother, Ptolemy XIV. Cleopatra later gave birth to Caesar's son, Caesarion, titled Ptolemy Caesar. Caesar hearing of an invasion in Asia Minor led by Pharnaces II of Pontus, the son of the old Roman enemy Mithridates, advanced there in 47 BC, and won a quick victory at the Battle of Zela. It was then that Caesar famously said: "Veni, Vidi, Vici" - "I came, I saw, I conquered."

In 46 BC Caesar went to North Africa to deal with the regrouping remnants of the pro-Pompeian forces under Cato the Younger and Titus Labienus. After a slight setback in the Battle of Ruspina he defeated them at the Battle of Thapsus. Much to Caesar's chagrin, Cato committed suicide. Caesar had wanted to pardon Cato, his most intractable foe, in order to gain popularity through further clemency. In 45 BC, he went to Spain, and won the final victory over the pro-Pompeian forces in the terrifying Battle of Munda. He said that before, he always had fought for victory, but in Munda he had fought for his life. He then returned to Rome; he had less than a year to live.

In that final year Caesar launched many reforms. He tightly regulated the distribution of free grain, keeping those who could afford private grain from having access to the grain dole. He reformed the calendar, changing from a Lunar to a Solar calendar and giving his gens name to the 7th month (July). This calendar, with minor changes made by Octavian (who would later rename the 8th month (August) after one of his titles) and Pope Gregory in 1582, has survived until now. He also reformed the debt problem. At the same time, he continued to accept enormous honors from the Senate. He was named Pater Patriae - "Father of his Country", and began wearing the clothing of the old Roman kings. This deepened the rift between Caesar and the aristocratic republican Senators, many of whom he had pardoned during the civil war. In 45 BC he had been named dictator for ten years. This was followed up in 44 BC with his appointment of dictator for life. A two-fold problem was created; firstly, all political power would be concentrated in the hands of Caesar for the foreseeable future, in effect subordinating the Senate to his whims; and secondly, only Caesar's death would end this. As such, a group of about 60 senators, led by Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Junius Brutus, conspired to assassinate Caesar in order to save the republic. They carried out their deed on the Ides of March 15 of March 44 BC, three days before Caesar was scheduled to go east to defeat the Parthians.

The Second Triumvirate and Octavian's triumph

After Caesar's assassination, his friend and chief lieutenant, Marcus Antonius, seized the last will of Caesar and using it in an inflammatory speech against the murderers, incited the mob against them. The murderers panicked and fled to Greece. In Caesar's will, his grand-nephew Octavianus who also was the adopted son of Caesar, was named as his political heir. Octavian returned from Greece (where he and his friends Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Gaius Maecenas had been helping in the gathering of the Macedonian legions for the planned invasion of Parthia) and raised a small army from among Caesar's veterans. After some initial disagreements, Antony, Octavian, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, formed the Second Triumvirate. Their combined strength gave the triumvirs absolute power. In 42 BC, they followed the assassins into Greece, and mostly due to the generalship of Antony, defeated them at the Battle of Philippi on the 23 of October.

In 40 BC, Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus negotiated the Pact of Brundisium. Antony received all the richer provinces in the east, namely Achaea, Macedonia and Epirus (roughly modern Greece), Bithynia, Pontus and Asia (roughly modern Turkey), Syria, Cyprus and Cyrenaica and he was very close to Egypt, then the richest state of all. Octavian on the other hand received the Roman provinces of the west: Italia (modern Italy), Gaul (modern France), Gallia Belgica (parts of modern Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg), and Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal), these territories were poorer but traditionally the better recruiting grounds; and Lepidus was given the minor province of Africa (modern Tunisia) to govern. Henceforth, the contest for supreme power would be between Antony and Octavian.

In the west, Octavian and Lepidus had first to deal with Sextus Pompeius, the surviving son of Pompey, who had taken control of Sicily and was running pirate operations in the whole of the Mediterranean, endangering the flow of the crucial Egyptian grain to Rome. In 36 BC, Lepidus, while besieging Sextus forces in Sicily, ignored Octavian's orders that no surrender would be allowed. Octavian then bribed the legions of Lepidus, and they deserted to him. This stripped Lepidus of all his remaining military and political power. Antony, in the east, was waging war against the Parthians. His campaign was not as successful as he would have hoped, though far more successful than Crassus. He took up an amorous relationship with Cleopatra, who gave birth to three children by him. In 34 BC, at the Donations of Alexandria, Antony "gave away" much of the eastern half of the empire to his children by Cleopatra. In Rome, this donation, the divorce of Octavia Minor and the affair with Cleopatra, and the seized testament of Antony (in which he famously asked to be buried in his beloved Alexandria) was used by Octavian in a vicious propaganda war accusing Antony of "going native", of being completely in the thrall of Cleopatra and of deserting the cause of Rome. He was careful not to attack Antony directly, for Antony was still quite popular in Rome; instead, the entire blame was placed on Cleopatra.

In 31 BC war finally broke out. Approximately 200 senators, one-third of the Senate, abandoned Octavian to support Antony and Cleopatra. The final confrontation of the Roman Republic occurred on 2 of September, 31 BC, at the naval Battle of Actium where the fleet of Octavian under the command of Agrippa routed the combined fleet of Antony and Cleopatra; the two lovers fled to Egypt. Due to Octavian's victory and his skillful use of propaganda, negotiation and bribery the legions of Antony in Greece, Asia Minor and Cyrenaica went over to his side.