Beard: Difference between revisions

m HOOKUP WITH SUGAR MUMMY IN MALAYSIA Tags: Replaced blanking |

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by Xong2 to version by Atlantic306. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (3229402) (Bot) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Redirect|Bearded|the British music magazine|Bearded (magazine)}} |

|||

SAY NO TO FAKE AGENT OF SUGAR MUMMY LET PUT AN END TO DOES FRAUDULENT AGENT HELLO FELLOW MALAYSIANS I want to use this medium to thank and appreciate Mrs Zafirah for a successful job well done by connecting me to a rich and wealthy sugar daddy who happen to become my sugar daddy I never though there are still true and reliable agent who can connect me because i have been dupe so many times by fake agent who claims to be an agent of sugar mummy and daddy hookup some of them even claim to work for the Asia dating venture. i spent little money but I never regretted because I got what I was looking for and right now am with him he payed me for the first night as agreed and he has been the one taking good care of me. Am so so happy and glad of having him am proud of him GOD bless the day I knew Mrs Zafirah and GOD bless you all for reading my message you can contact Mrs Zafirah via the same whatsapp number +601160904135 Please be wear of fraudsters because many of them claim to be Mrs Zafirah the only Mrs Zafirah I know uses only one whatsapp phone number Which is +601160904135 I wish you success in all what you are doing fellow Malaysians help me say a big thanks to Mrs Zafirah and I will continue to testifies your good work ANYWHERE I GO IN THIS WORLD GO ON WITH YOUR GOOD WORK AND DON'T? the only money i pay to hookup as my hookup form is 1210rm only no hidden fee again |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{Infobox anatomy |

|||

| Name = Beard |

|||

| Latin = barba |

|||

| GraySubject = |

|||

| GrayPage = |

|||

| Image =Baba in Nepal with a beard.jpg |

|||

| Caption = [[Hindu]] [[Sadhu]] with a goatee and moustache. |

|||

| Width = |

|||

| Image2 = |

|||

| Caption2 = |

|||

| ImageMap = |

|||

| MapCaption = |

|||

| Precursor = |

|||

| System = |

|||

| Artery = |

|||

| Vein = |

|||

| Nerve = |

|||

| Lymph = |

|||

| MeshName = |

|||

| MeshNumber = |

|||

| Code = |

|||

| Dorlands = |

|||

| DorlandsID = |

|||

}} |

|||

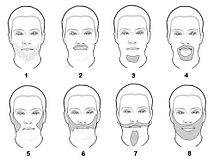

[[File:Baerte ohne text.jpg|thumb|Different types of beards : 1) Incipient 2) moustache 3) goatee or Mandarin 4) Spanish style 5) long sideburns 6) sideburn joined by his mustache 7) Style Van Dyke 8) full beard.]] |

|||

A '''beard''' is the collection of hair that grows on the chin and cheeks of humans and some non-human animals. In humans, usually only [[pubescent]] or adult males are able to grow beards. From an evolutionary viewpoint the beard is a part of the broader category of [[androgenic hair]]. It is a [[vestigial trait]] from a time when humans had hair on their face and entire body like the hair on [[gorilla]]s. The evolutionary loss of hair is pronounced in some populations such as [[indigenous American]]s and some east Asian populations, who have less facial hair, whereas people of European or South Asian ancestry and the [[Ainu people|Ainu]] have more facial hair. Women with [[hirsutism]], a hormonal condition of increased hairiness, or a rare genetic disorder known as [[hypertrichosis]] [[Bearded lady|may develop a beard]]. |

|||

Societal attitudes toward male beards have varied widely depending on factors such as prevailing cultural-religious traditions and the current era's fashion trends. Some religions (such as [[Sikhism]]) have considered a full beard to be absolutely essential for all males able to grow one, and mandate it as part of their official [[dogma]]. Other cultures, even while not officially mandating it, view a beard as central to a man's [[virility]], exemplifying such virtues as [[wisdom]], [[Physical strength|strength]], sexual prowess and high [[social status]]. However, in cultures where facial hair is uncommon (or currently out of fashion), beards may be associated with poor hygiene or a "savage", uncivilized, or even dangerous demeanor. |

|||

==Biology== |

|||

[[File:Aoki Shuzo.jpg|thumb|upright|An East Asian man with a full beard]] |

|||

The beard develops during [[puberty]]. Beard growth is linked to stimulation of hair follicles in the area by [[dihydrotestosterone]] (DHT), which continues to affect beard growth after puberty. Various hormones stimulate hair follicles from different areas. DHT, for example, may also promote short-term [[pogonotrophy]] (i.e., the growing of facial hair). For example, a scientist who chose to remain anonymous spent several weeks on a remote island in comparative isolation. He noticed that his beard growth diminished, but the day before he was due to leave the island it increased again, reaching unusually high rates of growth during the first day or two on the mainland. He studied the effect and concluded that the stimulus for increased beard growth was related to the resumption of sexual activity.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Effects of sexual activity on beard growth in man|journal=Nature|volume=226|issue=5248|year=1970|pmid=5444635|doi=10.1038/226869a0|pages=869–70}}</ref> However, at that time professional pogonologists, such as R.M. Hardisty, dismissed a connection.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hardisty|first1=R. M.|title=Shaving to impress|journal=Nature|volume=226|page=1277|year=1970|doi=10.1038/2261277a0|issue=5252}}</ref> Despite DHT's relationship with terminal body and facial hair growth, the dominant hormone in facial hair development is likely the male sex hormone [[testosterone]], with DHT more closely associated with beard growth speed rather than density (or "coverage"); moreover, neither hormone acts alone, depending instead on the quantity of androgen receptors on the face. Subjects with a greater preponderance of receptors will develop more terminal adult facial hairs.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Farthing|first1=MJ|title=Relationship between plasma testosterone and dihydrotestosterone concentrations and male facial hair growth|year=1982}}</ref> |

|||

Beard growth rate is also genetic.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Randall VA |title=Androgens and hair growth |journal=Dermatol Ther |volume=21 |issue=5 |pages=314–28 |year=2008 |pmid=18844710 |doi=10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00214.x}}</ref> An individual's genes determine the [[anagen phase]] of hair in different parts of the body. The anagen phase is the amount of time a hair follicle will grow before the hair falls out and is replaced by a new hair. This in turn determines the length of the hair on that part of the body.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-dont-chimpanzees-have-long-luscious-locks-1-180951387/|title=Why Don’t Chimpanzees Have Long, Luscious Locks?|last=Schultz|first=Colin|work=Smithsonian|access-date=2017-10-14|language=en}}</ref> The hairs of a bushy beard will have a relatively long anagen phase. The hairs of some men have shorter anagen phases and consequently have sparser shorter beards. The facial hair of most women and children has a very short anagen phase . Genes also determine whether the hair is a thick [[terminal hair]] like that of a bristle or a fine [[vellus hair]] like that on a child or womans face.. |

|||

===Evolution=== |

|||

[[File:Charles Darwin by Julia Margaret Cameron 2.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Charles Darwin]]]] |

|||

Biologists characterize beards as a [[secondary sexual characteristic]] because they are unique to one sex, yet do not play a direct role in reproduction. [[Charles Darwin]] first suggested possible [[evolution]]ary explanation of beards in his work ''[[The Descent of Man]]'', which hypothesized that the process of [[sexual selection]] may have led to beards.<ref>{{cite book |last=Darwin |first=Charles |title=The Descent Of Man And Selection In Relation To Sex |location= |publisher=Kessinger Publishing |year=2004 |page=554 }}</ref> Modern biologists have reaffirmed the role of sexual selection in the evolution of beards, concluding that there is evidence that a majority of females find men with beards more [[Sexual attraction|attractive]] than men without beards.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Dixson |first=A. |title=Sexual selection and the evolution of visually conspicuous sexually dimorphic traits in male monkeys, apes, and human beings |journal=Annu Rev Sex Res |year=2005 |volume=16 |issue= |pages=1–19 |doi= |pmid=16913285 |last2=Dixson |first2=B |last3=Anderson |first3=M }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Miller |first=Geoffry F. |chapter=How Mate Choice Shaped Human Nature: A Review of Sexual Selection and Human Evolution |title=Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology: Ideas, Issues, and Applications |editor-last=Crawford |editor-first=Charles B. |location= |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |pages=106, 111, 113 |isbn= }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Skamel |first=Uta |chapter=Beauty and Sex Appeal: Sexual Selection of Aesthetic Preferences |title=Evolutionary Aesthetics |editor-first=Eckhard |editor-last=Voland |location=New York |publisher=Springer |year=2003 |pages=173–183 |isbn=3-540-43670-7 }}</ref> |

|||

[[Evolutionary psychology]] explanations for the existence of beards include signalling [[sexual maturity]] and signalling [[Dominance hierarchy|dominance]] by increasing perceived size of jaws, and [[clean-shaven|clean-shaved]] faces are rated less dominant than bearded.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Puts | first1 = D. A. | title = Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans | doi = 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.02.005 | journal = Evolution and Human Behavior | volume = 31 | issue = 3 | pages = 157–175 | year = 2010 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> Some scholars assert that it is not yet established whether the sexual selection leading to beards is rooted in attractiveness (inter-sexual selection) or dominance (intra-sexual selection).<ref>{{cite book |last=Dixson |first=A. F. |title=Sexual selection and the origins of human mating systems |location=New York |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2009 |page=178 |isbn=978-0-19-955943-5 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=VRTniKE2liYC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> A beard can be explained as an indicator of a male's overall condition.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Randy |last=Thornhill |first2=Steven W. |last2=Gangestad |title=Human facial beauty: Averageness, symmetry, and parasite resistance |journal=Human Nature |volume=4 |issue=3 |pages=237–269 |doi=10.1007/BF02692201 |year=1993 }}</ref> The rate of facial hairiness appears to influence male attractiveness.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Barber |first=N. |title=The Evolutionary psychology of physical attractiveness: Sexual selection and human morphology |journal=Ethol Sociobiol |volume=16 |issue=5 |pages=395–525 |doi=10.1016/0162-3095(95)00068-2 |year=1995 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Etcoff |first=N. |title=Survival of the Prettiest: The Science of Beauty |location=New York |publisher=Doubleday |year=1999 |isbn=0-385-47854-2 }}</ref> The presence of a beard makes the male vulnerable in fights, which is costly, so biologists have speculated that there must be other evolutionary benefits that outweigh that drawback.<ref>{{cite book |last=Zehavi |first=A. |last2=Zahavi |first2=A. |year=1997 |title=The Handicap Principle |location=New York |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=213 |isbn=0-19-510035-2 }}</ref> Excess [[testosterone]] evidenced by the beard may indicate mild [[immunosuppression]], which may support [[spermatogenesis]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Folstad |first=I. |last2=Skarstein |first2=F. |title=Is male germ line control creating avenues for female choice? |journal=Behavioral Ecology |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=109–112 |year=1997 |doi=10.1093/beheco/8.1.109 }}</ref><ref>Folstad and Skarsein cited by {{cite book |last=Skamel |first=Uta |chapter=Beauty and Sex Appeal: Sexual Selection of Aesthetic Preferences |title=Evolutionary Aesthetics |editor-first=Eckhard |editor-last=Voland |location= |publisher=Springer |year=2003 |pages=173–183 |isbn= }}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=November 2016}} |

|||

===Ancient and classical world=== |

|||

====Lebanon==== |

|||

[[File:Anthropoid sarcophagus discovered at Cadiz - Project Gutenberg eText 15052.png|thumb|160px|right|The [[Phoenicians]], who originated in what is now [[Lebanon]], gave great attention to the beard, as can be seen in their sculptures.]] |

|||

The ancient Semitic civilization situated on the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent and centered on the coastline of modern [[Lebanon]] gave great attention to the hair and beard. The beard has mostly a strong resemblance to that affected by the Assyrians, familiar from their sculptures. It is arranged in three, four, or five rows of small tight curls, and extends from ear to ear around the cheeks and chin. Sometimes, however, in lieu of the many rows, there is one row only, the beard falling in tresses, which are curled at the extremity. There is no indication of the Phoenicians having cultivated mustachios.<ref>{{citation-attribution|{{cite book|last1=Rawlinson |first1=George |title=History of Phoenicia |year=1889 |publisher=Longmans, Green, and Co }}}}</ref> |

|||

====Mesopotamia==== |

|||

[[File:Sargon of Akkad.jpg|thumb|right|Bearded Akkadian mask featuring characteristic curls, presumed to represent either [[Sargon of Akkad|Sargon the Elder]] or his grandson [[Naram-Sin of Akkad|Naram-Sin]]]] |

|||

[[Mesopotamia]]n men of Semitic origin (Akkadians, Assyrians, Babylonians and Chaldeans) devoted great care to oiling and dressing their beards, using tongs and curling irons to create elaborate ringlets and tiered patterns. Unlike them, the non-Semitic [[Sumer]]ian men tended to shave off their facial hair (which is especially notable, for example, in the numerous statues of [[Gudea]], a ruler of [[Lagash]], as opposed to the depiction of the roughly contemporaneous Semitic ruler of Akkad, [[Naram-Sin of Akkad|Naram-Sin]], on his victory stele). |

|||

====Egypt==== |

|||

The highest ranking [[Ancient Egypt]]ians grew hair on their chins which was often dyed or [[henna]]ed (reddish brown) and sometimes plaited with interwoven gold thread. A metal false beard, or [[postiche]], which was a sign of sovereignty, was worn by kings and (occasionally) ruling queens. This was held in place by a ribbon tied over the head and attached to a gold chin strap, a fashion existing from about 3000 to 1580 BC. |

|||

====India==== |

|||

In Ancient India, the beard was allowed to grow long, a symbol of dignity and of wisdom, especially by ascetics ([[sadhu]]). The nations in the east generally treated their beards with great care and veneration, and the punishment for licentiousness and adultery was to have the beard of the offending parties publicly cut off. |

|||

====China==== |

|||

[[Confucius]] held that the human body was a gift from one's parents to which no alterations should be made. Aside from abstaining from body modifications such as tattoos, Confucians were also discouraged from cutting their hair, fingernails or beards. To what extent people could actually comply with this ideal depended on their profession; farmers or soldiers probably would not have grown a long beard because it would interfere with their work.{{Citation needed|date=April 2017}} |

|||

Most of the clay soldiers in the [[Terracotta Army]] have mustaches or goatees but shaved cheeks, which was likely the fashion of the [[Qin dynasty]].{{Citation needed|date=April 2017}} |

|||

====Iran==== |

|||

[[File:Mihr Ali 1813.jpg|80px|thumbnail|[[Fath-Ali Shah]], the second [[Qajar]] Shah of Persia had a long beard.]] |

|||

The [[Iranian people|Iranians]] were fond of long beards, and almost all the [[List of kings of Persia|Iranian kings]] had a beard. In ''Travels'' by [[Adam Olearius]], a king commands his steward's head to be cut off and then remarks, "What a pity it was, that a man possessing such fine mustachios, should have been executed." Men in the [[Achaemenid Empire|Achaemenid era]] wore long beards, with warriors adorning theirs with jewelry. Men also commonly wore beards during the [[Safavid dynasty|Safavid]] and [[Qajar dynasty|Qajar eras]]. |

|||

====Greece==== |

|||

The [[ancient Greeks]] regarded the beard as a badge or sign of [[virility]]; in the [[Homeric epics]], it had almost sanctified significance, and a common form of entreaty was to touch the beard of the person addressed.<ref>See, for example, Homer ''Iliad'' 1:500-1</ref> It was shaven only as a sign of mourning; it was then instead often left untrimmed. A smooth face was regarded as a sign of [[effeminacy]].<ref>Athen. xiii. 565 a (cited by Peck)</ref> The [[Sparta]]ns punished cowards by shaving off a portion of their beards. From the earliest times, however, the shaving of the upper lip was not uncommon. Greek beards were also frequently curled with tongs. |

|||

====Kingdom of Macedonia==== |

|||

[[File:Tetradrachm Ptolemaeus I obverse CdM Paris FGM2157.jpg|upright|thumb|right|A coin depicting a cleanly shaven [[Alexander the Great]].]] |

|||

In the time of [[Alexander the Great]] the custom of smooth [[shaving]] was introduced.<ref>Chrysippus ap. Athen. xiii. 565 a (cited by Peck)</ref> Reportedly, Alexander ordered his soldiers to be clean-shaven, fearing that their beards would serve as handles for their enemies to grab and to hold the soldier as he was killed. The practice of shaving spread from the [[Ancient Macedonians|Macedonians]], whose kings are represented on coins, etc. with smooth faces, throughout the whole known world of the Macedonian Empire. Laws were passed against it, without effect, at [[Rhodes]] and [[Byzantium]]; and even [[Aristotle]] conformed to the new custom,<ref>Diog. Laert.v. 1 (cited by Peck)</ref> unlike the other [[philosopher]]s, who retained the beard as a badge of their profession. A man with a beard after the Macedonian period implied a philosopher,<ref>cf. Pers.iv. 1, magister [[barbatus (disambiguation)|barbatus]] of Socrates (cited by Peck)</ref> and there are many allusions to this custom of the later philosophers in such proverbs as: [[Barba non facit philosophum|"The beard does not constitute a philosopher."]]<ref>{{lang-grc|πωγωνοτροφία φιλόσοφον οὐ ποιεῖ}}. De Is. et Osir. 3 (cited by Peck)</ref> |

|||

====Rome==== |

|||

Shaving seems to have not been known to the [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] during their early history (under the kings of Rome and the early Republic). Pliny tells us that P. Ticinius was the first who brought a [[barber]] to Rome, which was in the 454th year from the founding of the city (that is, around 299 BC). [[Scipio Africanus]] was apparently the first among the Romans who shaved his beard. However, after that point, shaving seems to have caught on very quickly, and soon almost all Roman men were clean-shaven; being clean-shaven became a sign of being Roman and not Greek. Only in the later times of the Republic did the Roman youth begin shaving their beards only partially, trimming it into an ornamental form; prepubescent boys oiled their chins in hopes of forcing premature growth of a beard.<ref>Petron. 75, 10 (cited by Peck)</ref> |

|||

Still, beards remained rare among the Romans throughout the Late Republic and the early Principate. In a general way, in Rome at this time, a long beard was considered a mark of slovenliness and squalor. The censors [[L. Veturius]] and [[P. Licinius]] compelled [[M. Livius]], who had been banished, on his restoration to the city, to be shaved, and to lay aside his dirty appearance, and then, but not until then, to come into the [[Roman Senate|Senate]].<ref>Liv.xxvii. 34 (cited by Peck)</ref> The first occasion of shaving was regarded as the beginning of [[manhood]], and the day on which this took place was celebrated as a festival.<ref>Juv.iii. 186 (cited by Peck)</ref> Usually, this was done when the young Roman assumed the ''[[toga virilis]]''. [[Augustus]] did it in his twenty-fourth year, [[Julius Caesar]] in his twentieth. The hair cut off on such occasions was consecrated to a god. Thus [[Nero]] put his into a golden box set with pearls, and dedicated it to [[Jupiter Capitolinus]].<ref>Suet. Ner.12 (cited by Peck)</ref> The Romans, unlike the Greeks, let their beards grow in time of mourning; so did Augustus for the death of Julius Caesar.<ref>Dio Cass. xlviii. 34 (cited by Peck)</ref> Other occasions of mourning on which the beard was allowed to grow were, appearance as a ''reus'', condemnation, or some public calamity. On the other hand, men of the country areas around Rome in the time of [[Marcus Terentius Varro|Varro]] seem not to have shaved except when they came to market every eighth day, so that their usual appearance was most likely a short [[Shaving|stubble]].<ref>Varro asked rhetorically how often the tradesmen of the country shaved between market days, implying (in chronologist E. J. Bickerman's opinion) that this did not happen at all: "quoties priscus homo ac rusticus Romanus inter nundinum barbam radebat?",[http://archimedes.fas.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/dict?name=ls&lang=la&word=nundinus&filter=CUTF8 Varr. ap. Non. 214, 30; 32]: see also E J Bickerman, ''Chronology of the Ancient World'', London (Thames & Hudson) 1968, at p.59.</ref> |

|||

In the second century AD the Emperor [[Hadrian]], according to [[Dion Cassius]], was the first of all the Caesars to grow a beard; [[Plutarch]] says that he did it to hide scars on his face. This was a period in Rome of widespread imitation of Greek culture, and many other men grew beards in imitation of Hadrian and the Greek fashion. Until the time of [[Constantine the Great]] the emperors appear in busts and coins with beards; but Constantine and his successors until the reign of [[Phocas]], with the exception of [[Julian the Apostate]], are represented as beardless. |

|||

====Celts and Germanic tribes==== |

|||

Late Hellenistic sculptures of [[Celts]]<ref>Examples (both in Roman copies): ''[[Dying Gaul]]'', ''[[Ludovisi Gaul]]''</ref> portray them with long hair and mustaches but beardless. |

|||

Among the [[Gaels|Gaelic]] Celts of Scotland and Ireland, men typically let their facial hair grow into a full beard, and it was often seen as dishonourable for a Gaelic man to have no facial hair.<ref name="Connolly-prologue">{{cite book |title=Contested island: Ireland 1460–1630 |last=Connolly |first=Sean J |year=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=7 |chapter=Prologue}}</ref><ref name="Gerald">[http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/topography_ireland.pdf ''The Topography of Ireland'' by Giraldus Cambrensis] (English translation)</ref><ref>Macleod, John, ''Highlanders: A History of the Gaels'' (Hodder and Stoughton, 1997) p43</ref> |

|||

[[Tacitus]] states that among the Catti, a [[Germanic people|Germanic]] tribe (perhaps the [[Chatten]]), a young man was not allowed to shave or cut his hair until he had slain an enemy. The [[Lombards]] derived their name from the great length of their beards (Longobards – Long Beards). When [[Otto the Great]] said anything serious, he swore by his beard, which covered his breast. |

|||

===Middle Ages=== |

|||

[[File:Charles IV-John Ocko votive picture-fragment.jpg|upright|thumb|right|[[Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor]].]] |

|||

In the [[Medieval Europe]], a beard displayed a [[knight]]'s [[virility]] and [[honour]].{{cn|date=November 2017}} For instance, the Castilian knight [[El Cid]] is described in ''[[The Lay of the Cid]]'' as "the one with the flowery beard". Holding somebody else's beard was a serious offence that had to be righted in a [[duel]].{{cn|date=November 2017}} |

|||

While most noblemen and knights were bearded, the Catholic clergy were generally required to be clean-shaven. This was understood as a symbol of their [[celibacy]]. The adoption of different beard styles and personal grooming had great cultural and political significance in the Early Middle Ages.<ref>[https://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.42.6.9 Ashby, S.P. (2016) Grooming the Face in the Early Middle Ages, Internet Archaeology 42.] Retrieved 30 August 2017</ref> |

|||

In pre-Islamic Arabia, men would apparently keep mustaches but shave the hair on their chins. Muhammad encouraged his followers to do the opposite, long chin hair but trimmed mustaches, to signify their break with the old religion. This style of beard subsequently spread along with Islam during the Muslim expansion in the Middle Ages. |

|||

===From the Renaissance to the present day=== |

|||

{{multiple issues| |

|||

{{Original research section|date=June 2009}} |

|||

{{Globalize|section|date=April 2014}}}} |

|||

[[File:明宣宗.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Xuande Emperor]] of Ming (1425-1435)]] |

|||

[[File:Black and white photo of emperor Meiji of Japan.jpg|upright|thumb|right|[[Emperor Meiji of Japan]] wore a full beard and moustache during most of his reign.]] |

|||

Most Chinese emperors of the [[Ming dynasty]] (1368–1644) appear with beards or mustaches in portraits. The exceptions are the [[Jianwen Emperor|Jianwen]] and [[Tianqi Emperor|Tianqi]] emperors, probably due to their youth - both died in their early 20's. |

|||

In the 15th century, most European men were clean-shaven. 16th-century beards were allowed to grow to an amazing length (see the portraits of [[John Knox]], [[Stephen Gardiner|Bishop Gardiner]], [[Reginald Pole|Cardinal Pole]] and [[Thomas Cranmer]]). Some beards of this time were the Spanish spade beard, the English square cut beard, the forked beard, and the stiletto beard. In 1587 [[Francis Drake]] claimed, in a [[figure of speech]], to have [[singed the King of Spain's beard]]. |

|||

During the Chinese [[Qing dynasty]] (1644–1911), the ruling [[Manchu]] minority were either clean-shaven or at most wore mustaches, in contrast to the [[Han Chinese|Han]] majority who still wore beards in keeping with the Confucian ideal. |

|||

In the beginning of the 17th century, the size of beards decreased in urban circles of Western Europe. In the second half of the century, being clean-shaven gradually become more common again, so much so that in 1698, [[Peter I of Russia|Peter the Great]] of Russia ordered men to shave off their beards, and in 1705 levied a [[beard tax|tax on beards]] in order to bring Russian society more in line with contemporary Western Europe.<ref>{{cite book |last=Corson |first1=Richard |title=Fashions in Hair: The First Five Thousand Years |edition=3 |location=London |publisher=Peter Owen Publishers |year=2005 |page=220 |isbn=978-0720610932 }}</ref> |

|||

====19th century==== |

|||

[[File:Thomas Swann of Maryland - photo portrait seated.jpg|right|thumb|upright|Maryland Governor [[Thomas Swann]] with a long [[goatee]]. Such beards were common around the time of the [[American Civil War]].]] |

|||

During the early nineteenth century, most men, particularly among the nobility and upper classes, went clean-shaven. There was, however, a dramatic shift in the beard's popularity during the 1850s, with it becoming markedly more popular.<ref name="Jacob Middleton 2006">Jacob Middleton, 'Bearded Patriarchs', History Today, Volume: 56 Issue: 2 (February 2006), 26–27.</ref> Consequently, beards were adopted by many leaders, such as [[Alexander III of Russia]], [[Napoleon III]] of France and [[Frederick III, German Emperor|Frederick III]] of Germany, as well as many leading statesmen and cultural figures, such as [[Benjamin Disraeli]], [[Charles Dickens]], [[Giuseppe Garibaldi]], [[Karl Marx]], and [[Giuseppe Verdi]]. This trend can be recognised in the United States of America, where the shift can be seen amongst the post-Civil War presidents. Before [[Abraham Lincoln]], no President wore a beard;<ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9Z6vCGbf66YC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA59#v=onepage&q&f=false | title=Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History | publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group | author=Sherrow, Victoria | year=2006 | page=59}}</ref> after Lincoln until [[Woodrow Wilson]], every President except [[Andrew Johnson]] and [[William McKinley]] had either a beard or a moustache of some sort. |

|||

The beard became linked in this period with notions of masculinity and male courage.<ref name="Jacob Middleton 2006"/> The resulting popularity has contributed to the stereotypical Victorian male figure in the popular mind, the stern figure clothed in black whose gravitas is added to by a heavy beard. |

|||

====20th century==== |

|||

By the early twentieth century, beards began a slow decline in popularity. Although retained by some prominent figures who were young men in the Victorian period (like [[Sigmund Freud]]), most men who retained facial hair during the 1920s and 1930s limited themselves to a moustache or a [[goatee]] (such as with [[Marcel Proust]], [[Albert Einstein]], [[Vladimir Lenin]], [[Leon Trotsky]], [[Adolf Hitler]], and [[Joseph Stalin]]). However, the later 20th and early 21st centuries saw beards making a comeback, particularly in the [[hippie]] subculture of the 1960s and the [[hipster (contemporary subculture)|hipster movement]] of the 2010s. |

|||

In China, the revolution of 1911 and subsequent May Fourth Movement of 1919 led the Chinese to idealise the West as more modern and progressive than themselves. This included the realm of fashion, and Chinese men began shaving their faces and cutting their hair short. Moustaches were however, still worn by prominent figures like [[Sun Yat-Sen]], [[Chiang Kai-shek]] and [[Lu Xun]].{{cn|date=November 2017}} |

|||

In the United States, meanwhile, popular movies portrayed heroes with clean-shaven faces and "[[crew cut]]s". Concurrently, the psychological [[mass marketing]] of [[Madison Avenue]] was becoming prevalent, and makers of [[safety razor]]s were among these marketers' early clients, including [[The Gillette Company]] and the [[American Safety Razor Company]]. The phrase ''[[wikt:five o'clock shadow|{{visible anchor|five o'clock shadow}}]]'', as a pejorative for stubble, was coined circa 1942 in advertising for Gem Blades, by the American Safety Razor Company, and entered popular usage. These events conspired to popularise short hair and clean-shaven faces as the only acceptable style for decades to come. The few men who wore the beard or portions of the beard during this period were frequently either elderly, Central European, members of a religious sect that required it, sailors, or in academia.{{cn|date=November 2017}} |

|||

==Beards in religion== |

|||

Beards also play an important role in some religions. |

|||

In [[Greek mythology]] and art, [[Zeus]] and [[Poseidon]] are always portrayed with beards, but [[Apollo]] never is. A bearded [[Hermes]] was replaced with the more familiar beardless youth in the 5th century BC. [[Zoroaster]], the 11th/10th century BC era founder of [[Zoroastrianism]] is almost always depicted with a beard. |

|||

In [[Norse mythology]], [[Thor]] the god of thunder is portrayed wearing a red beard. |

|||

===Christianity=== |

|||

[[File:Johannes Bessarion aport012.png|thumb|upright|[[Basilios Bessarion]]'s beard contributed to his defeat in the [[papal conclave, 1455|papal conclave of 1455]].<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Soykut | first1 = Mustapha | chapter = Chapter Nine: The Ottoman Empire and Europe in political history through Venetian and Papal sources | editor1-last = Birchwood | editor1-first = Matthew | editor2-last = Dimmock | editor2-first = Matthew | title = Cultural Encounters Between East and West, 1453–1699 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=U5zTAHQfI4MC | location = Newcastle upon Tyne | publisher = Cambridge Scholars Press | publication-date = 2005 | page = 170 | isbn = 9781904303411 | accessdate = 2014-10-28 | quote = [...] Bessarion later embraced the Catholic faith and in 1455 lost the election to become Pope with eight votes against fifteen from the cardinals. One of the arguments that was used against the election of Bessarion as Pope was that he still had a beard, even though he had converted to Catholicism, and insisted on wearing his Greek habit, which raised doubts on the sincerity of his conversion.}}</ref>]] |

|||

Iconography and art dating from the 4th century onward almost always portray [[Jesus]] with a beard. In paintings and statues most of the [[Old Testament]] Biblical characters such as [[Moses]] and [[Abraham]] and Jesus' [[New Testament]] [[Disciple (Christianity)|disciples]] such as [[St Peter]] appear with beards, as does [[John the Baptist]]. However, Western European art generally depicts [[John the Apostle]] as clean-shaven, to emphasize his relative youth. Eight of the figures portrayed in the painting entitled ''[[The Last Supper (Leonardo)|The Last Supper]]'' by [[Leonardo da Vinci]] are bearded. Mainstream Christianity holds [[Isaiah]] Chapter 50: Verse 6 as a [[prophecy]] of Christ's [[crucifixion]], and as such, as a description of Christ having his beard plucked by his tormentors. |

|||

[[File:PC Macarie Șotârcă.JPG|thumb|left|Orthodox priest with a long black beard]] |

|||

In [[Eastern Christianity]], members of the priesthood and monastics often wear beards, and religious authorities at times have recommended or required beards for all male believers.<ref>Note for example the [[Old Believers]] within the [[Russian Orthodox Church|Russian Orthodox]] tradition: {{cite encyclopedia |last= Paert |first= Irina |editor-first= John Anthony |editor-last= McGuckin |editor-link= John Anthony McGuckin |encyclopedia= The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, 2 Volume Set |title= Old Believers |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=JmFetR5Wqd8C |accessdate= 2014-10-28 |year= 2010 |publisher= John Wiley & Sons |isbn= 9781444392548 |pages= 420 |quote= Ritual prohibitions typical for all sections of the Old Believers include shaving beards (for men) and smoking tobacco.}}</ref> |

|||

[[Amish]] and [[Hutterite]] men shave until they marry and then grow a beard and are never thereafter without one, but it is a particular form of a beard (see [[Visual markers of marital status]]). Many [[Saint Thomas Christians|Syrian Christians]] from [[Kerala]] in India wore{{When|date=October 2014}} long beards. |

|||

In the 1160s Burchardus, the abbot of the [[Bellevaux Abbey|Cistercian monastery of Bellevaux]] in the Franche-Comté, wrote a treatise on beards.<ref>Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaevalis LXII, Apologiae duae: Gozechini epistola ad Walcherum; Burchardi, ut videtur, Abbatis Bellevallis Apologia de Barbis. Edited by R.B.C. Huygens, with an introduction on beards in the Middle Ages by [[Giles Constable]]. Turnholti 1985</ref> He regarded beards as appropriate for lay brothers but not for the priests among the monks. |

|||

At various times in its history and depending on various circumstances, the [[Catholic Church]] in the West permitted or prohibited facial hair (''barbae nutritio'' – literally meaning "nourishing a beard") for clergy.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02362a.htm |title=Catholic Encyclopedia entry |publisher=Newadvent.org |date= |accessdate=2011-11-24}}</ref> A decree of the beginning of the 6th century in either [[Carthage]] or the south of [[Gaul]] forbade clerics to let their hair and beards grow freely. The phrase "nourishing a beard" was interpreted in different ways, either as imposing a clean-shaven face or only excluding a beard that was too long. In relatively modern times, the first pope to wear a beard was [[Pope Julius II]], who, in 1511–1512, did so as a sign of mourning for the loss of the city of [[Bologna]]. [[Pope Clement VII]] let his beard grow at the time of the [[sack of Rome (1527)]] and kept it. All his successors did so until the death in 1700 of [[Pope Innocent XII]]. Since then, no pope has worn a beard. Most Latin-rite clergy are now clean-shaven, but [[Order of Friars Minor Capuchin|Capuchins]] and some others are bearded. Present canon law is silent on the matter.<ref>{{cite web|last1=McNamara|first1=Edward|title=Beards and Priests|url=http://www.zenit.org/en/articles/beards-and-priests|website=ZENIT news agency|accessdate=13 January 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Although most [[Protestant]] Christians regard the beard as a matter of choice, some have taken the lead in fashion by openly encouraging its growth as "a habit most natural, scriptural, manly, and beneficial" ([[Charles Spurgeon|C. H. Spurgeon]]).<ref>Spurgeon, C. H., ''Lectures to My Students, First Series, Lecture 8'' (Baker Book House, 1981) p 134.</ref> Some [[Messianic Judaism|Messianic Jews]] also wear beards to show their observance of the [[Old Testament]]. |

|||

[[Diarmaid MacCulloch]] writes:<ref>[Diarmaid MacCulloch (1996), ''Thomas Cranmer: A Life'', Yale University Press, p. 361]</ref> "There is no doubt that [[Thomas Cranmer|Cranmer]] mourned the dead king ([[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]])", and it was said that he showed his grief by growing a beard. However, |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

"it was a break from the past for a clergyman to abandon his clean-shaven appearance which was the norm for late medieval priesthood; with [[Martin Luther|Luther]] providing a precedent [during his exile period], virtually all the continental reformers had deliberately grown beards as a mark of their rejection of the old church, and the significance of clerical beards as an aggressive anti-Catholic gesture was well recognised in mid-[[Tudor England]]." |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

Male members of the [[Church of God in Christ, Mennonite]] in Moundridge, Kansas, refrain from shaving as they see man created in the image of God, and as God has a beard. They see their church as the One True Church. One of their tracts stresses the necessity of being bearded. |

|||

====LDS Church==== |

|||

[[File:Brigham Young by Charles William Carter.jpg|thumb|upright|Many early LDS Church leaders (such as Brigham Young, pictured) wore beards.]] |

|||

Since the mid-twentieth century, [[The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]] (LDS Church) has encouraged men to be clean-shaven,<ref name="oaks">{{cite journal |last= Oaks |first= Dallin H. |authorlink= Dallin H. Oaks |title= Standards of Dress and Grooming |url= http://lds.org/new-era/1971/12/standards-of-dress-and-grooming?lang=eng |journal= [[New Era (magazine)|New Era]] |date= December 1971 |publisher= [[LDS Church]] }}</ref> particularly those that serve in ecclesiastical leadership positions.<ref>{{citation |first= Peggy Fletcher |last= Stack |authorlink= Peggy Fletcher Stack |date= April 5, 2013 |title= How beards became barred among top Mormon leaders |url= http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/56042739-78/beard-beards-byu-church.html.csp |newspaper= [[The Salt Lake Tribune]] }}</ref> The church's encouragement of men's shaving has no theological basis, but stems from the general waning of facial hair's popularity in Western society during the twentieth century and its association with the [[hippie]] and [[drug culture]] aspects of the [[counterculture of the 1960s]], and has not been a permanent rule.<ref name="oaks" /> |

|||

After [[Joseph Smith]], many of the early presidents of the LDS Church, such as [[Brigham Young]] and [[Lorenzo Snow]], wore beards. Since [[David O. McKay]] became [[President of the Church (LDS Church)|church president]] in 1951, most LDS Church leaders have been clean-shaven. The church maintains no formal policy on facial hair for its general membership.<ref>{{cite news |first= Lynn |last= Arave |date= March 17, 2003 |title= Theology about beards can get hairy |url= http://www.deseretnews.com/article/970319/Theology-about-beards-can-get-hairy.html?pg=all |newspaper= Deseret News }}</ref> However, formal prohibitions against facial hair are currently enforced for young men providing two-year [[Mormon missionary|missionary]] service.<ref>{{cite journal |title= FYI: For Your Information |journal= [[New Era (magazine)|New Era]] |date= June 1989 |pages= 48–51 |url= http://lds.org/new-era/1989/06/fyi-for-your-information?lang=eng |accessdate= 2011-02-18}}</ref> Students and staff of the church-sponsored higher education institutions, such as [[Brigham Young University]] (BYU), are required to adhere to the [[Church Educational System Honor Code]],<ref name=BYUhouse3>{{cite book |last1= Bergera |first1= Gary James |last2= Priddis |first2= Ronald |year= 1985 |chapter= Chapter 3: Standards & the Honor Code |chapter-url= http://signaturebookslibrary.org/?p=13895 |title= Brigham Young University: A House of Faith |place= Salt Lake City |publisher= [[Signature Books]] |isbn= 0-941214-34-6 |oclc= 12963965 }}</ref> which states in part: "Men are expected to be clean-shaven; beards are not acceptable", although male BYU students are permitted to wear a neatly groomed [[moustache]].<ref>{{citation |contribution= Church Educational System Honor Code |title= Undergraduate Catalog, 2014-2015 |publisher= registrar.byu.edu, [[Brigham Young University]] |contribution-url= http://registrar.byu.edu/catalog/2014-2015ucat/GeneralInfo/HonorCode.php |year= 2014 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20141125225815/http://registrar.byu.edu/catalog/2014-2015ucat/GeneralInfo/HonorCode.php |archive-date= 2014-11-25 |dead-url= no }}</ref> A beard exception is granted for "serious skin conditions",<ref>{{citation |url= http://health.byu.edu/index2.php?page=services/beard.php |contribution= Services: Beard Exception |title= Student Health Center |publisher= BYU |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20141125225757/http://health.byu.edu/index2.php?page=services%2Fbeard.php |archive-date= 2014-11-25 |deadurl= yes |df= }}</ref> and for approved theatrical performances, but until 2015 no exception was given for any other reason, including religious convictions.<ref>{{citation |first= Julie |last= Turkewitznov |date= November 17, 2014 |title= At Brigham Young, Students Push to Lift Ban on Beards |url= https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/18/us/campaigning-to-change-the-cleanshaven-look-at-brigham-young-university.html |newspaper= [[The New York Times]] |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20141118191241/http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/18/us/campaigning-to-change-the-cleanshaven-look-at-brigham-young-university.html |archive-date= 2014-11-18 |deadurl= no }}</ref> In January 2015, BYU clarified that students who want a beard for religious reasons, like Muslims or Sikhs, may be granted permission after applying for an exception.<ref>{{citation |first= Abby |last= Phillip |date= January 14, 2015 |title= Brigham Young University adjusts anti-beard policies amid student protests |url= https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2015/01/14/brigham-young-university-adjusts-anti-beard-policies-amid-student-protests/ |newspaper= [[Washington Post]] }}</ref><ref>{{citation |first= Annie |last= Knox |date= January 15, 2015 |title= BYU clarifies beard policy; spells out exceptions |url= http://www.sltrib.com/2057823-155/ |newspaper= [[The Salt Lake Tribune]] }}</ref><ref>{{citation |first= Amy |last= McDonald |date= January 17, 2015 |title= Muslims celebrate BYU beard policy exemption |url= http://www.heraldextra.com/news/local/education/college/byu/muslims-celebrate-byu-beard-policy-exemption/article_ed90845c-677a-5ade-9e24-9350ba33e68f.html |newspaper= [[Provo Daily Herald]] }}</ref><ref>{{citation |url= http://www.standard.net/Faith/2015/01/19/BYU-makes-clear-there-are-3-exceptions-to-beard-ban.html |title= BYU beard ban doesn't apply to Muslim students |newspaper= [[Standard-Examiner]] |agency= ([[Associated Press|AP]]) |date= January 19, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150121001249/http://www.standard.net/Faith/2015/01/19/BYU-makes-clear-there-are-3-exceptions-to-beard-ban.html |archive-date= 2015-01-21 |deadurl= no}} Reprinted by ''[http://www.deseretnews.com/article/765666725/BYU-makes-clear-there-are-3-exceptions-to-beard-ban.html Deseret News]'', [http://www.ksl.com/?nid=148&sid=33159783 KSL], and [http://www.kutv.com/news/features/local-news/stories/BYU-makes-clear-there-are-3-exceptions-to-beard-ban-69912.shtml#.VL7x5kfF89Y KUTV].</ref> |

|||

BYU students led a campaign to loosen the beard restrictions in 2014,<ref>{{citation |first= Whitney |last= Evans |date= September 27, 2014 |title= Students rally for beard 'revolution' in Provo |url= http://www.deseretnews.com/article/865611874/Students-rally-for-beard-revolution-in-Provo.html?pg=all |newspaper= [[Deseret News]] }}</ref><ref>{{citation |first= Annie |last= Knox |date= September 26, 2014 |title= BYU student asks school to chop beard ban |url= http://www.sltrib.com/58458452-219/university-beards-beard-campus.html |newspaper= [[The Salt Lake Tribune]] |deadurl= yes |archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/20141125224803/http://www.sltrib.com/58458452-219/university-beards-beard-campus.html |archivedate= November 25, 2014 |df= }}</ref><ref>{{citation |first= Whitney |last= Evans |date= September 27, 2014 |title= Students protest BYU beard restriction |url= http://www.ksl.com/?nid=148&sid=31728643 |publisher= [[KSL-TV|KSL 5 News]] }}</ref><ref>{{citation |first= Annie |last= Cutler |date= September 26, 2014 |title= 'Bike for Beards' event part of BYU students' fight for facial hair freedom |url= http://fox13now.com/2014/09/26/bike-for-beards-event-part-of-byu-students-fight-for-facial-hair-freedom/ |publisher= [[KSTU|Fox 13 News (KSTU)]] }}</ref> but it had the opposite effect at [[Church Educational System]] schools: some who had previously been granted beard exceptions were found no longer to qualify, and for a brief period the [[LDS Business College]] required students with a registered exception to wear a "beard badge", which was likened to a "[[badge of shame]]". Some students also join in with [[shame|shaming]] their fellow beard-wearing students, even those with registered exceptions.<ref>{{citation |first= Annie |last= Knox |date= November 24, 2014 |title= Beard ban at Mormon schools getting stricter, students say |url= http://www.sltrib.com/1867918-155/beard-ban-at-mormon-schools-getting |newspaper= [[The Salt Lake Tribune]] }}</ref> |

|||

===Hinduism=== |

|||

[[File:"Sadhu", A Hindu Yogi, Bodhgaya Bihar India 2009.jpg|thumb|upright|Indian [[Sadhu]] with very long beard and [[dreadlocks]]]] |

|||

The ancient text followed regarding beards depends on the [[Deva (Hinduism)|Deva]] and other teachings, varying according to whom the devotee worships or follows. Many [[Sadhus]], [[Yogis]], or [[Sannyasa|Sannyasi]] keep beards, and represent all situations of life. [[Shaivism|Shaivite]] ascetics generally have beards, as they are not permitted to own anything, which would include a razor. The beard is also a sign of a nomadic and ascetic lifestyle. |

|||

[[Vaishnavism|Vaishnava]] devotees, typically of the [[ISKCON]] sect, are often clean-shaven as a sign of cleanliness. |

|||

===Judaism=== |

|||

{{Main article|Shaving in Judaism}} |

|||

[[File:רבי משה ברזובסקי.png|thumb|right|An ultra-Orthodox Jew with an unshaved beard and [[payot]] (sidelocks)]] |

|||

[[File:Dudi Kalish 1.jpg|thumb|upright|A Jewish man with a short trimmed beard]] |

|||

The [[Bible]] states in [[Leviticus]] 19:2, "You shall not round off the corners of your heads nor mar the corners of your beard." [[Talmud]]ic tradition explains it to mean that a man may not shave his beard with a [[razor]] with a single blade, since the cutting action of the blade against the skin "mars" the beard. Because [[scissors]] have two blades, some opinions in [[halakha]] (Jewish law) permit their use to trim the beard, as the cutting action comes from contact of the two blades, and not the blade against the skin. For this reason, some [[posek|poskim]] (Jewish legal deciders) rule that [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jews]] may use electric razors to remain clean-shaven, as such shavers cut by trapping the hair between the blades and the metal grating, [[halakha|halakhically]] a scissor-like action. Other poskim, like Zokon Yisrael KiHilchso,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://holmininternational613.com/books/BEARD_JEWISH_LAW-E.pdf|format=PDF|author= Gross, Rabbi Sholom Yehuda|title=The Beard in Jewish Law|accessdate= June 23, 2011}}See Zokon Yisrael KiHilchso</ref> maintain that electric shavers constitute a razor-like action, and consequently prohibit their use. |

|||

The ''[[Zohar]]'', one of the primary sources of [[Kabbalah]] ([[Jewish mysticism]]), attributes [[Sacred|holiness]] to the beard, specifying that hairs of the beard symbolize channels of subconscious holy energy that flows from above to the human soul. Therefore, most Hasidic Jews, for whom Kabbalah plays an important role in their religious practice, traditionally do not remove or even trim their beards. |

|||

Traditional Jews refrain from shaving, trimming the beard, and haircuts during certain times of the year like [[Passover]], [[Sukkot]], the [[Counting of the Omer]], and [[the Three Weeks]]. Cutting the hair is also restricted during the 30-day mourning period after the death of a close relative, known in Hebrew as the ''[[Bereavement in Judaism#Shloshim – Thirty days|Shloshim]]'' (thirty). |

|||

===Islam=== |

|||

[[File:Konstantin Kapidagli 002.jpg|thumb|An example of an Ottoman-style beard (Sultan Selim III).]] |

|||

{{See also|Islamic hygienical jurisprudence}} |

|||

====Shia==== |

|||

[[File:Mohammad Khatami - June 21, 2005.png|thumb|upright|left|[[Mohammad Khatami]] a Shia Muslim wears a beard]] |

|||

[[File:Shah Ismail I.jpg|thumb|upright|An example of a Safavid-style beard (Shah [[Ismail I]])]] |

|||

According to the Shia scholars, as per [[Sunnah]], the length of beard should not exceed the width of a fist. Trimming of facial hair is allowed, however, shaving it is ''haram'' (religiously forbidden).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.english.shirazi.ir/topics/beard|title=Ayatollah Sayed Sadiq Hussaini al-Shirazi » FAQ Topics » Beard|publisher=|accessdate=11 March 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sistani.org/english/qa/01136/|title=Beard - Question & Answer - The Official Website of the Office of His Eminence Al-Sayyid Ali Al-Husseini Al-Sistani|publisher=|accessdate=11 March 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.leader.ir/en/book/23?sn=5211|title=Practical Laws of Islam|publisher=|accessdate=11 March 2017}}</ref> |

|||

====Sunni==== |

|||

[[File:Asif Ali Sheikh - AsifAliSheikh.png|thumb|upright|left|Muslim beard in Sunni style with no moustache]] |

|||

Allowing the beard (''lihyah'' in Arabic) to grow and trimming the moustache is obligatory according to the [[Sunnah]] in Islam by consensus<ref>{{cite web|title=Ruling on shaving the beard|url=http://islamqa.com/en/ref/1189|work=Islam QA|accessdate=23 January 2012}}</ref> and is considered part of the ''[[fitra]]'' i.e. the way man was created. |

|||

[[Sahih al-Bukhari]], Book 72, [[Hadith]] 781 Narrated by [[Abdullah ibn Umar]] says "Allah's Apostle said, 'Cut the moustaches short and leave the beard (as it is).'"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/hadith/bukhari/072-sbt.php|title=Translation of Sahih Bukhari - CMJE|publisher=|accessdate=11 March 2017|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160417050422/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/hadith/bukhari/072-sbt.php|archivedate=17 April 2016|df=}}</ref> |

|||

[[Ibn Hazm]] reported that there was scholarly consensus that it is an obligation to trim the moustache and let the beard grow. He quoted a number of hadith as evidence, including the hadith of Ibn Umar quoted above, and the hadith of [[Zayd ibn Arqam]] in which Mohammed said: "Whoever does not remove any of his moustache is not one of us".<ref>Classed as saheeh by al-Tirmidhi</ref> Ibn Hazm said in al-Furoo'{{clarify|date=November 2015}}: "This is the way of our colleagues [i.e., group of scholars]". Inversely, in Turkish culture, moustaches are common. |

|||

The extent of the beard is from the cheekbones, level with the channel of the ears, until the bottom of the face. It includes the hair that grows on the cheeks. Hair on the neck is not considered a part of the beard and can be removed.<ref>{{cite web|title=Islamic definition of the beard|url=http://islamqa.info/en/69749|work=Islam QA|accessdate=3 May 2015}}</ref> |

|||

<ref>{{cite web|title=Islamic definition of a Sunnah Beard|url=http://www.sunnah-beard.com/beard-care-oil/|work=Sunnah Beard|accessdate=30 Jan 2016|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160207033239/http://www.sunnah-beard.com/beard-care-oil/|archivedate=2016-02-07|df=}}</ref> |

|||

In [[Sahih al-Bukhari|Bukhari]] and [[Sahih Muslim|Muslim]], Muhammad said "Five things are part of nature: to get circumcised, to remove the hair below one's [[navel]], to trim moustaches and nails and remove the [[Underarm hair|hair under the armpit]]."<ref>{{cite book|author1=Abu Muneer Ismail Davids|title=Dalīl al-wāfī li-adāʾ al-ʻUmrah|date=2006|publisher=Darussalam|isbn=9789960969046|page=76|edition=illustrated}}</ref> |

|||

===Rastafari movement=== |

|||

Male [[Rastafari movement|Rastafarians]] wear beards in conformity with injunctions given in the Bible, such as [[Leviticus]] 21:5: "They shall not make any baldness on their heads, nor shave off the edges of their beards, nor make any cuts in their flesh." The beard is a symbol of the covenant between God ([[Jah]] or [[Jehovah]] in Rastafari usage) and his people. |

|||

===Sikhism=== |

|||

[[File:Sikh.man.at.the.Golden.Temple.jpg|thumb|A Sikh man with a full beard]] |

|||

[[Guru Gobind Singh]], the tenth Sikh Guru, commanded the Sikhs to maintain unshorn hair, recognizing it as a necessary adornment of the body by Almighty God as well as a mandatory [[The Five Ks|Article of Faith]]. Sikhs consider the beard to be part of the nobility and dignity of their manhood. Sikhs also refrain from cutting their hair and beards out of respect for the God-given form. [[Kesh (Sikhism)|Kesh]], uncut hair, is one of [[the Five Ks]], five compulsory articles of faith for a baptized Sikh. As such, a Sikh man is easily identified by his turban and uncut hair and beard. |

|||

==Modern prohibition of beards== |

|||

===Civilian prohibitions=== |

|||

Beards may be prohibited in jobs which require the wearing of breathing masks,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://agency.governmentjobs.com/ebmud/job_bulletin.cfm?JobID=603612 |title=Job Bulletin |publisher=Agency.governmentjobs.com |date=2013-03-22 |accessdate=2014-02-26}}</ref> including airline pilots,<ref>{{cite web|title = Can Airline Pilots Have Beards?|url = http://www.mybeardandcompany.com/blogs/beard-care/46551617-can-airline-pilots-have-beards|accessdate = 2015-10-04|first = Beard and|last = Company}}</ref> firefighters,{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} and the oil and gas industry.{{Citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

|||

The Japanese municipality of [[Isesaki, Gunma]] decided to ban beards for male employees on May 19, 2010.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20100520a6.html |title=Gunma bureaucrats get beard ban | The Japan Times Online |publisher=Search.japantimes.co.jp |date=2010-05-20 |accessdate=2011-11-24}}</ref> |

|||

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit has found that employers may not require clean shaving without good reason, since this has a discriminatory effect against a large number of black men who are prone to [[razor bumps]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://openjurist.org/926/f2d/714/bradley-v-pizzaco-of-nebraska-inc-bradley |title=926 F2d 714 Bradley v. Pizzaco of Nebraska Inc Bradley |publisher=OpenJurist |date= |accessdate=2011-11-24}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=7 F.3d 795 (8th Cir. 1993) 68 Fair Empl.Prac.Cas. (Bna) 245, 62 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 42,611 Langston Bradley, Plaintiff, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Intervenor-Appellant, v. Pizzaco of Nebraska, Inc., D.B.a Domino's Pizza; Domino's Pizza, Inc., Defendants-Appellees |url=http://federal-circuits.vlex.com/vid/langston-pizzaco-domino-pizza-36071559 |work=United States Federal Circuit Courts Decisions Archive |publisher=vLex |accessdate=5 June 2012 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131204063954/http://federal-circuits.vlex.com/vid/langston-pizzaco-domino-pizza-36071559 |archivedate=4 December 2013 |df= }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=How to Grow a Healthy Beard for Black Men |url=http://beardbulk.com/ |accessdate=22 February 2016}}</ref> |

|||

====Sports==== |

|||

The [[International Boxing Association (amateur)|International Boxing Association]] prohibits the wearing of beards by amateur [[Boxing|boxers]], although the [[Amateur Boxing Association of England]] allows exceptions for Sikh men, on condition that the beard be covered with a fine net.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Rules of Amateur Boxing|url=http://www.abae.co.uk/aba/index.cfm/about-the-sport/the-rules-of-amateur-boxing/|archive-url=https://archive.is/20120716225735/http://www.abae.co.uk/aba/index.cfm/about-the-sport/the-rules-of-amateur-boxing/|dead-url=yes|archive-date=16 July 2012|publisher=[[Amateur Boxing Association of England]]|accessdate=27 May 2011|df=}}</ref> |

|||

===Armed forces=== |

|||

{{Main article|Facial hair in the military}} |

|||

{{See also|Religious symbolism in the United States military#Personal apparel and grooming}} |

|||

Depending on the country and period, facial hair was either prohibited in the army or an integral part of the uniform. For example, the French Foreign Legion's combat engineers are all required to be bearded. |

|||

==Styles== |

|||

{{main article|List of facial hairstyles}} |

|||

[[File:Pedro II of Brazil - Brady-Handy.jpg|thumb|upright|Emperor [[Pedro II of Brazil]] (1825-1891) wore a full beard from circa 1851.]] |

|||

Beard hair is most commonly removed by [[shaving]] or by trimming with the use of a beard trimmer. If hair is left only on the chin, the style is a [[goatee]]. |

|||

* [[Chinstrap beard|Chinstrap]]: a beard with long sideburns that comes forward and ends under the chin. |

|||

* [[Chin curtain]]: similar to the chinstrap beard but covers the entire chin. |

|||

* [[Shenandoah (beard)|Shenandoah]]: similar to the chinstrap. |

|||

* [[Designer stubble]]: A short growth of the male beard that was popular in the West in the 1980s. |

|||

* [[Goatee]]: A tuft of hair grown on the chin, sometimes resembling that of a billy goat. |

|||

* [[Hulihee]]: clean-shaven chin with fat chops connected at the moustache. |

|||

* [[Sideburns]]: hair grown from the temples down the cheeks toward the jawline. |

|||

* [[Van dyke beard|Van Dyke]]: a goatee accompanied by a moustache. |

|||

* [[Soul patch]]: a small beard just below the lower lip and above the chin. |

|||

==In art== |

|||

Beards are sometimes the subject of art<ref>{{cite web |title=Guy shaves half his beard, then glues in random objects to make it whole again |author=Inigo del Castillo |date=14 April 2015 |url=http://www.lostateminor.com/2015/04/14/guy-shaves-half-his-beard-then-glues-in-random-objects-to-make-it-whole-again/}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2878840/Artist-Incredibeard-takes-hipster-beard-art-trend-outrageous-new-lengths-amazing-facial-hair-sculptures.html |title=A Christmas tree, snowman and an OCTOPUS! Artist Incredibeard takes hipster 'beard art' trend to new lengths with amazing facial hair sculptures |author=Deni Kirkova |date=18 December 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Bob ("bphillipp") |date=December 16, 2014 |title=This man's incredible beard is an evolving work of art (18 Photos) |url=http://thechive.com/2014/12/16/this-mans-incredible-beard-is-an-evolving-work-of-art-18-photos/}}</ref> and competition. The [[World Beard and Moustache Championships]] take place every other year; contestants are evaluated by creativeness and uniqueness among other criteria. The longest beard that a person has ever possessed was 17 feet long and belonged to [[Hans Langseth]]<ref>{{cite web |title=The World's Longest Beard Is One Of The Smithsonian's Strangest Artifacts |url=http://www.lostateminor.com/2015/04/14/guy-shaves-half-his-beard-then-glues-in-random-objects-to-make-it-whole-again/ |author=Natasha Geiling |website=smithsonian.com |date=November 19, 2014}}</ref> (the longest beard of a living person is 8 feet<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/longest-beard-living-male |title=Longest beard – living male |website=guinnessworldrecords.com}}</ref>). |

|||

==In animals== |

|||

[[File:Bearded Pigs2.jpg|thumb|[[Bornean bearded pig]]s]] |

|||

The term "beard" is also used for a collection of stiff, hair-like feathers on the centre of the breast of [[Domestic turkey|turkeys]]. Normally, the turkey's beard remains flat and may be hidden under other feathers, but when the bird is displaying, the beard become erect and protrudes several centimetres from the breast. |

|||

Several animals are termed "bearded" as part of their common name. Sometimes a beard of hair on the chin or face is prominent but for some others, "beard" may refer to a pattern or colouring of the pelage reminiscent of a beard. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Barbatus (disambiguation)]], a common Latin name, meaning "bearded" |

|||

* [[Joseph Palmer (communard)]] defended himself from being forcibly shaved in 1830 |

|||

* [[The Beards (Australian band)]] |

|||

* [[World Beard and Moustache Championships]] |

|||

* [[Moustache]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

* {{HDCA|title=Barba}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* [[Reginald Reynolds]]: ''Beards: Their Social Standing, Religious Involvements, Decorative Possibilities, and Value in Offence and Defence Through the Ages'' (Doubleday, 1949) ({{ISBN|0-15-610845-3}}) |

|||

* Helen Bunkin, Randall Williams: ''Beards, Beards, Beards'' (Hunter & Cyr, 2000) ({{ISBN|1-58838-001-7}}) |

|||

* Allan Peterkin: ''One Thousand Beards. A Cultural History of Facial Hair'' ([[Arsenal Pulp Press]], 2001) ({{ISBN|1-55152-107-5}}) |

|||

* ''A Dictionary of Early Christian Beliefs'', David W. Bercot, Editor, pg 66–67. |

|||

* Thomas S. Gowing: ''The Philosophy of Beards'' (J. Haddock, 1854) ; reprinted 2014 by the [[British Library]], {{ISBN|9780712357661}} . |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons|Beard}} |

|||

* {{Wikibooks-inline|Shaving}} |

|||

* {{cite EB1911|wstitle=Beard|volume=3|short=x}} |

|||

{{Human hair}} |

|||

[[Category:Facial hair]] |

|||

[[Category:Hairstyles]] |

|||

Revision as of 03:37, 22 December 2017

| Beard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | barba |

| TA98 | A16.0.00.018 |

| TA2 | 7058 |

| FMA | 54240 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A beard is the collection of hair that grows on the chin and cheeks of humans and some non-human animals. In humans, usually only pubescent or adult males are able to grow beards. From an evolutionary viewpoint the beard is a part of the broader category of androgenic hair. It is a vestigial trait from a time when humans had hair on their face and entire body like the hair on gorillas. The evolutionary loss of hair is pronounced in some populations such as indigenous Americans and some east Asian populations, who have less facial hair, whereas people of European or South Asian ancestry and the Ainu have more facial hair. Women with hirsutism, a hormonal condition of increased hairiness, or a rare genetic disorder known as hypertrichosis may develop a beard.

Societal attitudes toward male beards have varied widely depending on factors such as prevailing cultural-religious traditions and the current era's fashion trends. Some religions (such as Sikhism) have considered a full beard to be absolutely essential for all males able to grow one, and mandate it as part of their official dogma. Other cultures, even while not officially mandating it, view a beard as central to a man's virility, exemplifying such virtues as wisdom, strength, sexual prowess and high social status. However, in cultures where facial hair is uncommon (or currently out of fashion), beards may be associated with poor hygiene or a "savage", uncivilized, or even dangerous demeanor.

Biology

The beard develops during puberty. Beard growth is linked to stimulation of hair follicles in the area by dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which continues to affect beard growth after puberty. Various hormones stimulate hair follicles from different areas. DHT, for example, may also promote short-term pogonotrophy (i.e., the growing of facial hair). For example, a scientist who chose to remain anonymous spent several weeks on a remote island in comparative isolation. He noticed that his beard growth diminished, but the day before he was due to leave the island it increased again, reaching unusually high rates of growth during the first day or two on the mainland. He studied the effect and concluded that the stimulus for increased beard growth was related to the resumption of sexual activity.[1] However, at that time professional pogonologists, such as R.M. Hardisty, dismissed a connection.[2] Despite DHT's relationship with terminal body and facial hair growth, the dominant hormone in facial hair development is likely the male sex hormone testosterone, with DHT more closely associated with beard growth speed rather than density (or "coverage"); moreover, neither hormone acts alone, depending instead on the quantity of androgen receptors on the face. Subjects with a greater preponderance of receptors will develop more terminal adult facial hairs.[3]

Beard growth rate is also genetic.[4] An individual's genes determine the anagen phase of hair in different parts of the body. The anagen phase is the amount of time a hair follicle will grow before the hair falls out and is replaced by a new hair. This in turn determines the length of the hair on that part of the body.[5] The hairs of a bushy beard will have a relatively long anagen phase. The hairs of some men have shorter anagen phases and consequently have sparser shorter beards. The facial hair of most women and children has a very short anagen phase . Genes also determine whether the hair is a thick terminal hair like that of a bristle or a fine vellus hair like that on a child or womans face..

Evolution

Biologists characterize beards as a secondary sexual characteristic because they are unique to one sex, yet do not play a direct role in reproduction. Charles Darwin first suggested possible evolutionary explanation of beards in his work The Descent of Man, which hypothesized that the process of sexual selection may have led to beards.[6] Modern biologists have reaffirmed the role of sexual selection in the evolution of beards, concluding that there is evidence that a majority of females find men with beards more attractive than men without beards.[7][8][9]

Evolutionary psychology explanations for the existence of beards include signalling sexual maturity and signalling dominance by increasing perceived size of jaws, and clean-shaved faces are rated less dominant than bearded.[10] Some scholars assert that it is not yet established whether the sexual selection leading to beards is rooted in attractiveness (inter-sexual selection) or dominance (intra-sexual selection).[11] A beard can be explained as an indicator of a male's overall condition.[12] The rate of facial hairiness appears to influence male attractiveness.[13][14] The presence of a beard makes the male vulnerable in fights, which is costly, so biologists have speculated that there must be other evolutionary benefits that outweigh that drawback.[15] Excess testosterone evidenced by the beard may indicate mild immunosuppression, which may support spermatogenesis.[16][17]

History

Ancient and classical world

Lebanon

The ancient Semitic civilization situated on the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent and centered on the coastline of modern Lebanon gave great attention to the hair and beard. The beard has mostly a strong resemblance to that affected by the Assyrians, familiar from their sculptures. It is arranged in three, four, or five rows of small tight curls, and extends from ear to ear around the cheeks and chin. Sometimes, however, in lieu of the many rows, there is one row only, the beard falling in tresses, which are curled at the extremity. There is no indication of the Phoenicians having cultivated mustachios.[18]

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamian men of Semitic origin (Akkadians, Assyrians, Babylonians and Chaldeans) devoted great care to oiling and dressing their beards, using tongs and curling irons to create elaborate ringlets and tiered patterns. Unlike them, the non-Semitic Sumerian men tended to shave off their facial hair (which is especially notable, for example, in the numerous statues of Gudea, a ruler of Lagash, as opposed to the depiction of the roughly contemporaneous Semitic ruler of Akkad, Naram-Sin, on his victory stele).

Egypt

The highest ranking Ancient Egyptians grew hair on their chins which was often dyed or hennaed (reddish brown) and sometimes plaited with interwoven gold thread. A metal false beard, or postiche, which was a sign of sovereignty, was worn by kings and (occasionally) ruling queens. This was held in place by a ribbon tied over the head and attached to a gold chin strap, a fashion existing from about 3000 to 1580 BC.

India

In Ancient India, the beard was allowed to grow long, a symbol of dignity and of wisdom, especially by ascetics (sadhu). The nations in the east generally treated their beards with great care and veneration, and the punishment for licentiousness and adultery was to have the beard of the offending parties publicly cut off.

China

Confucius held that the human body was a gift from one's parents to which no alterations should be made. Aside from abstaining from body modifications such as tattoos, Confucians were also discouraged from cutting their hair, fingernails or beards. To what extent people could actually comply with this ideal depended on their profession; farmers or soldiers probably would not have grown a long beard because it would interfere with their work.[citation needed]

Most of the clay soldiers in the Terracotta Army have mustaches or goatees but shaved cheeks, which was likely the fashion of the Qin dynasty.[citation needed]

Iran

The Iranians were fond of long beards, and almost all the Iranian kings had a beard. In Travels by Adam Olearius, a king commands his steward's head to be cut off and then remarks, "What a pity it was, that a man possessing such fine mustachios, should have been executed." Men in the Achaemenid era wore long beards, with warriors adorning theirs with jewelry. Men also commonly wore beards during the Safavid and Qajar eras.

Greece

The ancient Greeks regarded the beard as a badge or sign of virility; in the Homeric epics, it had almost sanctified significance, and a common form of entreaty was to touch the beard of the person addressed.[19] It was shaven only as a sign of mourning; it was then instead often left untrimmed. A smooth face was regarded as a sign of effeminacy.[20] The Spartans punished cowards by shaving off a portion of their beards. From the earliest times, however, the shaving of the upper lip was not uncommon. Greek beards were also frequently curled with tongs.

Kingdom of Macedonia

In the time of Alexander the Great the custom of smooth shaving was introduced.[21] Reportedly, Alexander ordered his soldiers to be clean-shaven, fearing that their beards would serve as handles for their enemies to grab and to hold the soldier as he was killed. The practice of shaving spread from the Macedonians, whose kings are represented on coins, etc. with smooth faces, throughout the whole known world of the Macedonian Empire. Laws were passed against it, without effect, at Rhodes and Byzantium; and even Aristotle conformed to the new custom,[22] unlike the other philosophers, who retained the beard as a badge of their profession. A man with a beard after the Macedonian period implied a philosopher,[23] and there are many allusions to this custom of the later philosophers in such proverbs as: "The beard does not constitute a philosopher."[24]

Rome

Shaving seems to have not been known to the Romans during their early history (under the kings of Rome and the early Republic). Pliny tells us that P. Ticinius was the first who brought a barber to Rome, which was in the 454th year from the founding of the city (that is, around 299 BC). Scipio Africanus was apparently the first among the Romans who shaved his beard. However, after that point, shaving seems to have caught on very quickly, and soon almost all Roman men were clean-shaven; being clean-shaven became a sign of being Roman and not Greek. Only in the later times of the Republic did the Roman youth begin shaving their beards only partially, trimming it into an ornamental form; prepubescent boys oiled their chins in hopes of forcing premature growth of a beard.[25]

Still, beards remained rare among the Romans throughout the Late Republic and the early Principate. In a general way, in Rome at this time, a long beard was considered a mark of slovenliness and squalor. The censors L. Veturius and P. Licinius compelled M. Livius, who had been banished, on his restoration to the city, to be shaved, and to lay aside his dirty appearance, and then, but not until then, to come into the Senate.[26] The first occasion of shaving was regarded as the beginning of manhood, and the day on which this took place was celebrated as a festival.[27] Usually, this was done when the young Roman assumed the toga virilis. Augustus did it in his twenty-fourth year, Julius Caesar in his twentieth. The hair cut off on such occasions was consecrated to a god. Thus Nero put his into a golden box set with pearls, and dedicated it to Jupiter Capitolinus.[28] The Romans, unlike the Greeks, let their beards grow in time of mourning; so did Augustus for the death of Julius Caesar.[29] Other occasions of mourning on which the beard was allowed to grow were, appearance as a reus, condemnation, or some public calamity. On the other hand, men of the country areas around Rome in the time of Varro seem not to have shaved except when they came to market every eighth day, so that their usual appearance was most likely a short stubble.[30]

In the second century AD the Emperor Hadrian, according to Dion Cassius, was the first of all the Caesars to grow a beard; Plutarch says that he did it to hide scars on his face. This was a period in Rome of widespread imitation of Greek culture, and many other men grew beards in imitation of Hadrian and the Greek fashion. Until the time of Constantine the Great the emperors appear in busts and coins with beards; but Constantine and his successors until the reign of Phocas, with the exception of Julian the Apostate, are represented as beardless.

Celts and Germanic tribes

Late Hellenistic sculptures of Celts[31] portray them with long hair and mustaches but beardless.

Among the Gaelic Celts of Scotland and Ireland, men typically let their facial hair grow into a full beard, and it was often seen as dishonourable for a Gaelic man to have no facial hair.[32][33][34]

Tacitus states that among the Catti, a Germanic tribe (perhaps the Chatten), a young man was not allowed to shave or cut his hair until he had slain an enemy. The Lombards derived their name from the great length of their beards (Longobards – Long Beards). When Otto the Great said anything serious, he swore by his beard, which covered his breast.

Middle Ages

In the Medieval Europe, a beard displayed a knight's virility and honour.[citation needed] For instance, the Castilian knight El Cid is described in The Lay of the Cid as "the one with the flowery beard". Holding somebody else's beard was a serious offence that had to be righted in a duel.[citation needed]

While most noblemen and knights were bearded, the Catholic clergy were generally required to be clean-shaven. This was understood as a symbol of their celibacy. The adoption of different beard styles and personal grooming had great cultural and political significance in the Early Middle Ages.[35]

In pre-Islamic Arabia, men would apparently keep mustaches but shave the hair on their chins. Muhammad encouraged his followers to do the opposite, long chin hair but trimmed mustaches, to signify their break with the old religion. This style of beard subsequently spread along with Islam during the Muslim expansion in the Middle Ages.

From the Renaissance to the present day

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Most Chinese emperors of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) appear with beards or mustaches in portraits. The exceptions are the Jianwen and Tianqi emperors, probably due to their youth - both died in their early 20's.

In the 15th century, most European men were clean-shaven. 16th-century beards were allowed to grow to an amazing length (see the portraits of John Knox, Bishop Gardiner, Cardinal Pole and Thomas Cranmer). Some beards of this time were the Spanish spade beard, the English square cut beard, the forked beard, and the stiletto beard. In 1587 Francis Drake claimed, in a figure of speech, to have singed the King of Spain's beard.