Greece–Turkey relations: Difference between revisions

m →The Aegean conflict: +link |

|||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

There are several issues at stake based on how this continental shelf is defined. One is protecting Turkey's shipping lanes as the Dardanelles feed into the Aegean (despite international law protecting this). A second is on the rights to mineral wealth (which has yet to be found). A third is on the 1950s flight zone, which impacts the military (a non-issue that was challenged two decades later, after the Cyprus invasion, to match the continental shelf claim by Turkey). Ultimately, fear of sovereignty loss is what's driving this conflict. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Greek reaction with the 1974 militarisation of the Greek islands near Turkey, and the Turkish creation of the 1975 Izmir army base (as large as the entire Greek army itself with amphibious capabilities) has created permanent military tensions. |

There are several issues at stake based on how this continental shelf is defined. One is protecting Turkey's shipping lanes as the Dardanelles feed into the Aegean (despite international law protecting this). A second is on the rights to mineral wealth (which has yet to be found). A third is on the 1950s flight zone, which impacts the military (a non-issue that was challenged two decades later, after the Cyprus invasion, to match the continental shelf claim by Turkey). Ultimately, fear of sovereignty loss is what's driving this conflict. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Greek reaction with the 1974 militarisation of the Greek islands near Turkey, and the Turkish creation of the 1975 Izmir army base (as large as the entire Greek army itself with amphibious capabilities) has created permanent military tensions. |

||

In recent years, the Blue Homeland policy of Turkey positions it in the Mediterranean as a sea power. Greece's fear, often explicitly communicated by Turkey's politicians in the media, is that Turkey wants to renegotiate borders otherwise determined by international law.<ref>{{cite news|title=Erdogan: Turkey gave away Aegean islands in 1923|publisher=naftemporiki|url=http://www.naftemporiki.gr/story/1153625/erdogan-turkey-gave-away-aegean-islands-in-1923}}</ref><ref name="ekathimerini">{{cite news|title=Erdogan disputes Treaty of Lausanne, prompting response from Athens|publisher=ekathimerini|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/212433/article/ekathimerini/news/erdogan-disputes-treaty-of-lausanne-prompting-response-from-athens}}</ref><ref name="ekathimerini.com">{{cite news|title=Turkish FM disputes Lausanne Treaty |publisher=ekathimerini|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/220905/article/ekathimerini/news/turkish-fm-disputes-lausanne-treaty}}</ref><ref name="Erdogan's talk of 'kinsmen' in Thra">{{cite news|title=Erdogan's talk of 'kinsmen' in Thrace raises concerns in Greece|publisher=ekathimerini|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/212931/article/ekathimerini/news/erdogans-talk-of-kinsmen-in-thrace-raises-concerns-in-greece}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=CHP head slams Greek defense minister, vows to take back 18 islands 'occupied by Greece' in 2019|url= http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/chp-head-slams-greek-defense-minister-vows-to-take-back-18-islands-occupied-by-greece-in-2019-124635|access-date=6 January 2018|website=Hürriyet Daily News}}</ref><ref name="Ahval">{{cite news|title="Greece should not test our patience" – Turkish opposition party |url= https://ahvalnews.com/greece-turkey/greece-should-not-test-our-patience-turkish-opposition-party|access-date=6 January 2018 | work =Ahval|date= 21 December 2017}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/238835/article/ekathimerini/news/turkish-defense-minister-sparks-controversy-again|title=Turkish defense minister sparks controversy, again {{!}} Kathimerini|website=www.ekathimerini.com|language=en|access-date=2019-04-21}}</ref> |

In recent years, the [[Blue Homeland]] policy of Turkey positions it in the Mediterranean as a sea power. Greece's fear, often explicitly communicated by Turkey's politicians in the media, is that Turkey wants to renegotiate borders otherwise determined by international law.<ref>{{cite news|title=Erdogan: Turkey gave away Aegean islands in 1923|publisher=naftemporiki|url=http://www.naftemporiki.gr/story/1153625/erdogan-turkey-gave-away-aegean-islands-in-1923}}</ref><ref name="ekathimerini">{{cite news|title=Erdogan disputes Treaty of Lausanne, prompting response from Athens|publisher=ekathimerini|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/212433/article/ekathimerini/news/erdogan-disputes-treaty-of-lausanne-prompting-response-from-athens}}</ref><ref name="ekathimerini.com">{{cite news|title=Turkish FM disputes Lausanne Treaty |publisher=ekathimerini|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/220905/article/ekathimerini/news/turkish-fm-disputes-lausanne-treaty}}</ref><ref name="Erdogan's talk of 'kinsmen' in Thra">{{cite news|title=Erdogan's talk of 'kinsmen' in Thrace raises concerns in Greece|publisher=ekathimerini|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/212931/article/ekathimerini/news/erdogans-talk-of-kinsmen-in-thrace-raises-concerns-in-greece}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=CHP head slams Greek defense minister, vows to take back 18 islands 'occupied by Greece' in 2019|url= http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/chp-head-slams-greek-defense-minister-vows-to-take-back-18-islands-occupied-by-greece-in-2019-124635|access-date=6 January 2018|website=Hürriyet Daily News}}</ref><ref name="Ahval">{{cite news|title="Greece should not test our patience" – Turkish opposition party |url= https://ahvalnews.com/greece-turkey/greece-should-not-test-our-patience-turkish-opposition-party|access-date=6 January 2018 | work =Ahval|date= 21 December 2017}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/238835/article/ekathimerini/news/turkish-defense-minister-sparks-controversy-again|title=Turkish defense minister sparks controversy, again {{!}} Kathimerini|website=www.ekathimerini.com|language=en|access-date=2019-04-21}}</ref> |

||

<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/238846/article/ekathimerini/news/akars-remarks-not-based-on-reason-greek-defense-minister-says|title=Akar's remarks 'not based on reason,' Greek Defense Minister says {{!}} Kathimerini|website=www.ekathimerini.com|language=en|access-date=2019-04-21}}</ref> |

<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ekathimerini.com/238846/article/ekathimerini/news/akars-remarks-not-based-on-reason-greek-defense-minister-says|title=Akar's remarks 'not based on reason,' Greek Defense Minister says {{!}} Kathimerini|website=www.ekathimerini.com|language=en|access-date=2019-04-21}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:29, 25 May 2022

| |

Greece |

Turkey |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Greece, Ankara | Embassy of Turkey, Athens |

Greece and Turkey have a competitive relationship with a long history and complex issues. Turkey was formed in 1923 and is considered the legal successor of the Ottoman Empire. Greece was recognised as an independent state by the Ottoman Empire in 1830. Culturally, Greeks and Turks have had relations as early as the 6th century CE.[citation needed]

Greece and Turkey since their formation have used real and imagined trauma of each other to justify their nationalism.[1] Yet, Greek-Turkish feuding was not a significant factor in international relations from 1930 to 1955 and during the cold war decades, domestic and bipolarity politics limited their competitiveness.[2][3] However, by the mid-1990s and decades to follow, the restraint on their rivalry was removed and both nations had become each other's biggest security risk.[4][5]

Control of the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean remain the basis of their rivalry. Post World War II the UNCLOS treaty, decolonisation of Cyprus and the addition of the Dodecanese to Greece’s territory has been what unpins their turbulent contemporary history and relations. There are several issues that are frequent in their current relations, which include territory disputes over the sea and air, minority rights, and Turkey's relationship with the European Union and its members especially Cyprus.[6][7] Control over energy pipelines is increasingly a focus in their relations.

Diplomatic missions

The first official diplomatic contacts between Greece and the Ottoman Empire occurred in 1830.[8] Consular relations between Greece and the Ottoman Empire were established in 1834.[9] A embassy opened in 1853 in Istanbul, discontinued during periods of crisis after and eventually transferred to the new capital Ankara in 1923 when Turkey was formed.[9]

- Turkey's missions in Greece include its embassy in Athens and consulates general in Thessaloniki, Komotini and Rhodes.

- Greece's missions in Turkey include its embassy in Ankara and consulates general in Istanbul, İzmir and Edirne.

Background

For three thousand years, the land that comprises modern Greece and modern Turkey before their division as nation states had a long shared history.

Modern day Greece is territory that was during the classical period mostly controlled by Ancient Greek city states and kingdoms (900–146 BC), the Macedonian Empire (335–323 BC) and subsequent Hellenistic States (323–146 BC) following by the Roman era starting with the Roman Republic (146–27 BC), then the Roman Empire (27 BC–395 AD), and in the medieval period the Byzantine Empire (395–1204, 1261–1453) before the conquest by the Ottoman Empire until the Greek revolution that formed Greece.

The Greek presence in Asia Minor dates at least from the Late Bronze Age (1450 BC).[10] Starting around 1200 BC, the coast of Turkey's Anatolia was heavily settled by Aeolian and Ionian Greeks, by the 6th century BC conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire, then 334 Alexander the Great's Macedonian Empire followed by the Hellenistic States and the Roman era (Roman Republic, Roman Empire and Byzantine Empire), the subsequent colonisation by Turkic people with powers such as the Seljuq Empire (1037–1194), the Seljuq Sultanate of Rum (1077–1307) and the Ottoman Empire (1299–1923) until its defeat during World War 1 and the subsequent Turkish revolution that formed Turkey.

The Byzantine Empire and Ottoman Empire, although different regimes to the modern nations of Greece and Turkey, factor into the nations' modern relations as heritage.[11] Some academics claim Turkey is not a successor state but the legal continuation of the Ottoman Empire as a Republic.[12][13] Some view the Byzantine Empire, the Roman Empire during the medieval era, the medieval expression of a Greek nation and a pre-modern nation state.[14]

Greek and Turk relations: 6th–19th centuries

The Göktürks of the First Turkic Khaganate, which came to prominence in 552 CE, were the first Turkic state to use the name Türk politically.[15] The first contact with the Romans (Byzantine Empire) is believed to be 563. [16][17] The 10th century saw the rise of the Seljuk Turks.[18] Following their rise and subsequent fall, the Ottoman dynasty filled the vacuum and become the Ottoman Empire. In 1453, the Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire. They followed by conquering its splinter states, such as the Despotate of the Morea in 1460, the Empire of Trebizond in 1461, and the Principality of Theodoro in 1475.

All of modern Greece by the time of the capture of the Desporate of the Morea was under Ottoman authority, with the exception of some of the islands. Life would have several dimensions living under the Ottoman Empire, which included autonomy under the church, extra taxes and slavery. The Romioi in various places of the Greek peninsula would at times rise up against Ottoman rule, which were of mixed scale and impact. Greek nationalism started to appear in the 18th century and in March 1821, the Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire began.

Greece and Ottoman Empire relations: 1822–1923

Following the Greek war of independence, Greece was formed as an independent state in 1830. The relations between Greece and the Ottoman Empire were shaped by two concepts: the Eastern Question and the Megali Idea.[19] There were five wars that directly and indirectly linked all conflict, and which saw Greece double its territory that was previously under Ottoman possession.

With the Allies victory in World War I, Greece was rewarded with territorial acquisitions, specifically Western Thrace (Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine) and Eastern Thrace and the Smyrna area (Treaty of Sèvres). Greek gains were largely undone by the subsequent Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922).[20]

Greece occupied Smyrna on 15 May 1919, while Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later Atatürk), who was to become the leader of the Turkish opposition to the Treaty of Sèvres, landed in Samsun on May 19, 1919, an action that is regarded as the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence. He united the protesting voices in Anatolia and set in motion a nationalist movement to repel the Allied armies that had occupied the Ottoman Empire and establish new borders for a sovereign Turkish nation. The Turkish nation would be Western in civilization and elevated its Turkish culture (which had faded under Arab culture), which included disassociating Islam from Arab culture and restricted into the private sphere.[21] Having created a separate government in Ankara, Kemal's government did not recognise the Treaty of Sèvres and fought to have it revoked.

On 1 November 1922, the Turkish Parliament in Ankara formally abolished the Sultanate and the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) ended all conflict and replaced previous treaties to constitute modern Turkey. It also provided for a Population exchange between Greece and Turkey, with certain exceptions that would impact the future relations of Greece and Turkey.

There were atrocities and ethnic cleansing by both sides during this period. The war with Greece and the revolutionary Turks saw both sides commit atrocities. The Greek genocide was the systematic killing of the Christian Ottoman Greek population of Anatolia which started before the World War I, continued during the war and its aftermath (1914–1922).

History

Initial relations between Greece and Turkey: 1923–1945

The post-war leaders of Turkey and Greece were determined to establish normal relations between the two states and a treaty was concluded. Following the population exchange, Greece no longer wished hostility but negotiations stalled because of the issue of valuations of the properties of the exchanged populations.[22][23] Driven by Eleftherios Venizelos in co-operation with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, as well as İsmet İnönü's government, a series of treaties were signed between Greece and Turkey in 1930 which, in effect, restored Greek-Turkish relations and established a de facto alliance between the two countries.[24] As part of these treaties, Greece and Turkey agreed that the Treaty of Lausanne would be the final settlement of their respective borders, while they also pledged that they would not join opposing military or economic alliances and to stop immediately their naval arms race.[24]

The Balkan Pact of 1934 was signed, in which Greece and Turkey joined Yugoslavia and Romania in a treaty of mutual assistance and settled outstanding issues (Bulgaria refused to join). Embassies were constructed as a result. Both leaders recognised the need for peace as it resulted in more friendly relations. Venizelos nominated Atatürk for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934.[25]

Greece was a signatory to a 1936 agreement that gives Turkey control over the Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits and regulates the transit of naval warships. The nations signed the 1938 Salonika Agreement which abandoned the demilitarised zones along the Turkish border with Greece, a result of the Treaty of Lausanne.[26]

Turkey otherwise followed a course of relative international isolation during the period of Atatürk's Reforms in the 1920s and 1930s. Greece would also be distracted by internal matters when it brought back republican rule with the Second Hellenic Republic from 1924 to 1935 and then fell into military dictatorship between 1936 until 1941. Turkey remained neutral during the Second World War while Greece fell under Axis occupation from 1941 until 1945.

In 1941, due to Turkey's neutrality during the war, Britain lifted the blockade and allowed shipments of grain to come from the Turkey to relieve the great famine in Athens during the Axis occupation. Using the vessel SS Kurtuluş, foodstuffs were collected by a nationwide campaign of Kızılay (Turkish Red Crescent) with the operation funded by the American Greek War Relief Association and the Hellenic Union of Constantinopolitans.[27]

Despite the stabilisation of relations between the nations in this period, the Greek minority that remained in Turkey faced discriminatory targeting.

- The first occasion and in anticipation of WWII in 1941, there was the incident of the Twenty Classes which was the conscription of non-Muslims males who were sent in labour battalions.

- The second, and more destructively in 1942, Turkey imposed the Varlık Vergisi, a special tax, which heavily impacted the non-Muslim minorities of Turkey. Officially, the tax was devised to fill the state treasury that would have been needed had Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union invaded the country. However, the main reason for the tax was to nationalize the Turkish economy by reducing minority populations' influence and control over the country's trade, finance, and industries.[28]

Post World War II relations: 1945–1982

The early Cold War aligned the international policies of the two countries with the Western Bloc. Following the power vacuum left by the Axis occupation at the end of the war, a Greek Civil War erupted that was one of the first conflicts of the Cold War. It represented the first example of Cold War postwar involvement on the part of the Allies in the internal affairs of a foreign country.[29] Turkey was a focus for the Soviet Union due to foreign control of the straights; it would be a central reason for the outbreak of the Cold War [30] In 1950 both fought alongside each other at the Korean War; in 1952, both countries joined NATO; and in 1953 Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia formed a new Balkan Pact for mutual defence against the Soviet Union.

Despite this, the think-tank Geopolitical Futures claims three events contributed to the deterioration of bilateral relations after World War II[31]

- The Dodecanese archipelago. By virtue of Italy being defeated in the second world war, the long-standing issue since the Venizelos–Tittoni agreement between Greece and Italy[33] was resolved to Greece's favour in 1946 to Turkey's chagrin as it changed the balance of power.[34] Although Turkey renounced claims to the Dodecanese in the Treaty of Lausanne, future administrations wanted them for security reasons, and possibly due to the Cyprus issue.[34]

- The decolonization of Cyprus. Conflict broke out between the Greeks and Turks on the island instead of the needed state building process. In the 1950s, the pursuit of enosis became a part of Greece's national policy.[35] Taksim became the slogan by some of the Turkish Cypriots in reaction to enosis. Tensions would increase between Greece and Turkey, and the Cyprus dispute weakened the Greek government of George Papandreou and triggered, in April 1967, a military coup. The junta staged a coup against the Cypriot President and Archbishop Makarios. Soon after, Turkey—using its guarantor status arising from the trilateral accords of the 1959–1960 Zürich and London Agreement—invaded Cyprus and remains to this day on the island.

- The U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Starting from 1958 and expanded in 1982 for the issue of territorial waters—UNCLOS replaced the older 'freedom of the seas' concept, dating from the 17th century. According to this concept, national rights were limited to a specified belt of water extending from a nation's coast lines, usually 3 nautical miles (5.6 km; 3.5 mi) (three-mile limit). By 1967, only 30 nations still used the old three nautical mile convention.[36] It was ratified by Greece in 1972 but Turkey has not ratified it, asking for a bilateral solution since 1974 which uses the mid-line of the Aegean instead[37]

In 1955, the Adnan Menderes government is believed to have orchestrated the Istanbul pogrom, which targeted the city's substantial Greek ethnic minority.[38] In September 1955 a bomb exploded close to the Turkish consulate in Greece's second-largest city, Thessaloniki, also damaging the Atatürk Museum, site of Atatürk's birthplace. The damage to the house was minimal, with some broken windows.[39] In retaliation, in Istanbul thousands of shops, houses, churches and even graves belonging to members of the ethnic Greek minority were destroyed within a few hours, over a dozen people were killed and many more injured.[40] The ongoing struggle between Turkey and Greece over control of Cyprus, and Cypriot intercommunal violence, formed part of the backdrop to the pogrom. Deflecting domestic attention to Cyprus was politically convenient for the Turkish Menderes government, which was suffering from an ailing economy. Although a minority, the Greek population played a prominent role in the city's business life, making it a convenient scapegoat during the economic crisis in the mid-1950s.[41]

In 1964 Turkish prime minister İsmet İnönü renounced the Greco-Turkish Treaty of Friendship of 1930 and took actions against the Greek minority.[42][43] An estimated 50,000 Greeks were expelled.[44] A 1971 Turkish law nationalized religious high schools and closed the Halki seminary on Istanbul's Heybeli Island which had trained Greek Orthodox clergy since 1844 and remains to this day an issue in diplomatic relations.

Contemporary history and issues

In recent decades, relations have become entangled with other nations. However, it's still about who has control over the Aegean Sea and the eastern Mediterranean. Since the 1990s, the countries have pursued a strategy of encircling each other, which has made their conflict expand to other countries—and pulled in the EU. While Cyprus and rights over the Aegean remain unresolved, the discovery of hydrocarbons reframes their disputes. And importance.

In 1986 by the border at the Evros River, a Greek soldier was shot after an offer to trade cigarettes. His death sparked outrage. In 1987, a Turkish survey ship, the Simsik, was ordered to be sunk to the bottom of the Greek waters if it floated too close. It nearly did. In 1995 the uninhabited rock island Imia, where both countries claim jurisdiction, had them close to starting a war.

The problem has grown. Lesser incidents often occur[45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54] – where both sides exchange fire – which does not help when tensions fly high. Despite this, there has been some progress.

Positive relations

In 1995, relations began to change with the Greek election of Kostas Simitis who redefined priorities but it wasn't until the meeting of the foreign ministers the following years that this was noticed.[55][56] In 1998, the capture of the Kurdish separatist Abdullah Ocalan – on the way from the Greek embassy in Kenya – and the related fallout led to the Greek foreign minister resigning,[57] whose replacement was with a cheer squad member for discussions with Turkey. In 1999, violent earthquakes hit both countries and saw an outpouring of goodwill.

In the years that followed, relations improved.[58] They included agreements on fighting organised crime, reducing military spending, preventing illegal immigration, and clearing land mines on the border. More significantly, Greece lifted its opposition to Turkey's accession to the EU, bringing some Turkish delight. However, even though there was a change to the weather, it did not change the atmosphere on the issues that mattered.[59]

The Aegean conflict

The UN sea treaty UNCLOS evolved in 1982 and came into force in 1994. Turkey is not a signatory. The conflict is whether the Greek islands are allowed a continental shelf, the basis of claiming rights over the sea. Turkey disputes that Greece can claim 12 miles off the coast of their islands, which the sea treaty permits, implying only the mainland has this right. There's a good reason why this definition matters. It would restrict Turkey and give Greece dominant control of the Aegean. The EU requires the sea treaty's membership as a pre-condition. Turkey on the other hand, has made a continental claim to split the Aegean Sea in the middle.

There are several issues at stake based on how this continental shelf is defined. One is protecting Turkey's shipping lanes as the Dardanelles feed into the Aegean (despite international law protecting this). A second is on the rights to mineral wealth (which has yet to be found). A third is on the 1950s flight zone, which impacts the military (a non-issue that was challenged two decades later, after the Cyprus invasion, to match the continental shelf claim by Turkey). Ultimately, fear of sovereignty loss is what's driving this conflict. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Greek reaction with the 1974 militarisation of the Greek islands near Turkey, and the Turkish creation of the 1975 Izmir army base (as large as the entire Greek army itself with amphibious capabilities) has created permanent military tensions.

In recent years, the Blue Homeland policy of Turkey positions it in the Mediterranean as a sea power. Greece's fear, often explicitly communicated by Turkey's politicians in the media, is that Turkey wants to renegotiate borders otherwise determined by international law.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66] [67]

Cyprus and the EU

The EU, of which Greece has been a member since 1981, interplay with the relations of Greece and Turkey in three different ways.

The first is through Turkey's accession. Turkey has been a candidate for membership for several decades. For example, in the 1980s after Greece was admitted in the EU, Greece concentrated its diplomatic efforts on barring Turkey's admission to the EU.[68] Concerns about Turkey like its human rights record and Greece's veto ultimately had Turkey side-lined by the EU. Domestically, this contributed to the shift away from Turkey's founding secular doctrine Kemalism and the rise of political Islam. The change was popular in inland Turkey because it adjusted the government's amnesia of the Ottoman Empire's past. It also evolved to an alternate identity of European orientation, as a regional center in the emerging Eurasian political formation.[69]

The second reason is due to the historical issue of Cyprus. The 1990s saw EU accession friction of Cyprus which was parallel to military tension.[69] In 1994, Greece and Cyprus agreed on a security doctrine that would mean any Turkish attempt on Cyprus would cause war for Greece. In 1997 Cyprus purchased two Soviet-era missile systems, the S-300s, resulting in a Turkish uproar; Greece did a swap and installed them on Crete against heavy whimpering. Negotiations never settled the division on the island in the 1990s because of the non-negotiable by the Turkish side to recognise North Cyprus as an independent state. When Cyprus joined the EU in 2002, the negotiation took a different flare. With Greece and Cyprus as EU members, this has become an EU issue; but with the island only 60 miles from Turkey, it also remains a national security issue for Turkey.

The third reason is due to EU policy. Turkey's migrant crisis has also had a big impact on its relationship with the EU. The enforcement of the arms embargo against Libya brought other EU members into conflict with Turkey on Operation Irini. The gas drilling on disputed territory with Greece with the RV MTA Oruç Reis led to EU sanctions[70][71][72]

Energy pipelines

The countries have pursued a strategy of encircling each other. Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, both Greece and Turkey viewed each other with suspicion as they developed relations with the new countries.[73] It wasn't until 1995, however, that this fear materialised.[68] Greece formed a defense cooperation agreement with Syria and between 1995 and 1998 established good relations with Turkey's other neighbors, Iran and Armenia. In reaction, Turkey spoke with Israel in 1996, which caused outroar by the Arab countries.

The 2010 discovery of gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean first by Israel and then Egypt, has created new energy to fan the disputes.[74] The historical security issues of the Aegean and Cyprus are now a focal point to resolving Europe's energy needs. For example, the 2016 Turkey-Israel reconciliation led to Greece torpedoing the 2017 Cyprus UN talks due to their relationship's risk for developing a gas pipeline.[74] In 2019, the east Mediterranean gas forum was created, including seven countries but excluding Turkey.[74] Turkey would work from 2018 with Libya to extend its economic rights over the sea, which has led to recent tensions with other members of the EU. This instability over the status of the Aegean and Cyprus prevents the needed investment from developing pipelines to Europe.

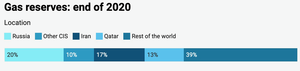

The region is considered the end-point for east–west pipelines.[69] In 2007, the countries inaugurated the Greek-Turkish natural gas pipeline giving Caspian gas its first direct Western outlet.[75] The Caspian Sea is one of the oldest oil-producing regions: it's estimated to have 48 billion barrels of oil in proven and probable reserves.[76] That's comparable to one year and a bit of global oil consumption. Its estimated 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas[76] is enough to satisfy two years of global gas consumption. The opening up of these fields is recent after more than 20 years of negotiation following the 2018 A Convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea.[77]

Outside of the Caspian Sea nations, there are other suppliers that wish to leverage the geographical positioning of the nations. Most recently, in May 2022, Greece signed a deal with the UAE for the distribution of its liquefied natural gas, a nation which ranks 7th in the world and 3% of global supply of natural gas.[78][79]

Minority rights

Since the formation of Turkey, minority rights have been an issue. The treaty of Lausanne provided for the protection of the Greek Orthodox Christian minority in Turkey and the Muslim minority in Greece.

Minorities in both countries since have been affected by the state of relations of the nations. They are used as a point of leverage, using the principle of reciprocity. For example, Turkey would put pressure on the Greek minority in Turkey when the Cyprus issue escalated in the 1960s. Turkey put the election of Muftis by the Muslim Turkish minority in Greece as a precondition for opening the Halki Seminary which was closed in 1971. Greece in 1972 as a reaction, closed the Turkish school in Rhodes. Turkey in recent years has used its cultural heritage, such as the Sumela Monastery, in order to achieve specific political ends.[80][81]

Both nations have done their share of unjust actions over the years. Some examples include:

- During world war two, the nationalisation of industry with the Varlık Vergisi that targeted minorities and especially Greeks

- The scapegoating of Greeks due to Turkey's economic problems that resulted in the Istanbul pogrom

- The Greek junta deporting Turkish citizens on the Dodecanese in 1967

- Article 19 of the Nationality Code established in 1955 two classes of Greek citizenship, whereby "non-Greek descent" lost their citizenship if they left the country. By the time of its abolition in 1998, 60,000 people has lost their citizenship and the abolition had no retroactive effect.[82]

In recent years, the main issues are the election of Muftis (currently controlled by Greek authorities) and the reopening of the Halki Seminary. Greece's hesitance could be solved if the Mufti's were stripped of authority of jurisdiction.[83] Turkey's precondition to open the Halki Seminary is considered unnecessary: it's purely a political decision[84] though the Greek government had promised Erdoğan that two Mosques would be built in Athens.[85]

In both cases, and in the words of former Greek prime minister George Papandreou, the respective nations would benefit if they treated the minorities as citizens not foreigners.[83]

Migrants

Turkey has become a transit country for people entering Europe.[87] In 2015, the route that passes from Turkey to Greece and then through the Balkan countries became the most used route for migrants escaping conflicts and war in the Middle East and North Africa, while irregular migration from further East continues.[88] Turkey assumed the role of guardian of the Schengen area, protecting it from irregular migration.[88] This, combined with the migrant crisis – has resulted in it being a key issue between Turkey and the EU.[88] People moving across the border of both nations are a common sight and frequent cause of incidents.[89][90][91][92][93][94][better source needed]

In 2016, there was a EU-Turkey deal on migrant crisis. Despite some success with the four-year agreement extended to 2022, there have been several incidents[95][96] and in 2019 the Greek government warned that a new migrant crisis similar to the previous one will repeat,[97] though this has yet to happen.

Turkish insurgents and asylum seekers

During the 2010 trial for an alleged plot to stage a military coup dating back to 2003, named Sledgehammer, the conspirators were accused of planning attacks on mosques, triggering a conflict with Greece by shooting down one of Turkey's own warplanes and then accusing Greeks of this and planting bombs in Istanbul to pave the way for a military takeover.[98][99][100]

Greece over the years has arrested on many occasions members of the DHKP-C who planned attacks in Turkey.[101][102][103][104] Turkey has accused Greece of supporting terrorists such as the DHKP-C.[105]

Turkey has seen a slide to authoritarianism[106] resulting in Turkish refugees becoming more common, like politician Leyla Birlik accused of insulting the president. This is especially since the failed 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, where 995 people applied for asylum (including military personnel which caused tensions) immediately after and have kept the newsrooms busy[107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118] More than 1,800 Turkish citizens requested asylum in Greece in 2017, making it a Greek drama as it included those who plotted the assassination[119][120] Sometimes, this causes tensions between the nations in other areas.[121][122][123]

Sports relations

- The Greece–Turkey football rivalry is one of Europe's major rivalries between two national teams.

- Çağla Büyükakçay-Maria Sakkari tennis duo of Turkey and Greece respectively won the ITF Circuit finals in Dubai, United Arab Emirates on 14 November 2015 by beating İpek Soylu and Elise Mertens.

- In 2002, Turkey and Greece made an unsuccessful attempt to jointly host the 2008 UEFA European Football Championship. The bid was one of the four candidacies that was recommended to the UEFA Executive Committee, the joint Austria/Switzerland bid winning the right to host the tournament.

Timeline

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1923 | 30 January | Turkey and Greece sign the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations agreement |

| 24 July | Treaty of Lausanne is signed. It would come into force 6 August 1924. | |

| 1926 | 26 June | Mahalli Idareler Kanunu (the local government act; no. 1151/1927), concerning the local administration of Imbros and Tenedos was published which stripped the islands of their local governance.[124] This was seen as revoking article 14 of the Treaty of Lausanne; it's argued the provisions were simply never observed in the first place.[125] |

| 1933 | 14 September | Greece and Turkey sign Pact of Cordial Friendship.[126] |

| 1934 | 9 February | Greece and Turkey, as well as Romania and Yugoslavia sign the Balkan Pact, a mutual defense treaty. |

| 1938 | 27 April | Greece and Turkey sign the "Additional Treaty to the Treaty of Friendship, Neutrality, Conciliation and Arbitration of October 30th, 1930, and to the Pact of Cordial Friendship of September 14th, 1933.[127] |

| 1941 | 6 October | SS Kurtuluş starts carrying first Turkish aid to Greece to alleviate the Great Famine during the Axis occupation of Greece. |

| 1942 | 11 November | Turkey enacts Varlık Vergisi. Industry was nationalised and targeted the Greek minority |

| 1947 | 10 February | Despite Turkish objections, the victorious powers of World War II transfer the Dodecanese islands to Greece, through the Treaty of Peace with Italy. |

| 31 March | Handover ceremony of the Dodecanese to Greece by the British authorities [128] | |

| 1950 | Greece and Turkey both fight at the Korean War at the side of the UN forces.[129] | |

| 1952 | 18 February | Greece and Turkey officially become members of NATO.[130] |

| 1953 | 28 February | Balkan Pact (1953) between Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia |

| 1955 | 6–7 September | Istanbul pogrom where the Greek population of Istanbul were targetted. |

| 1963 | 21 December | Bloody Christmas (1963) occurred, which was the beginning of the Cypriot intercommunal violence that brought the Greek and Turkish communities into civil war |

| 1964 | Turkish prime minister İsmet İnönü renounced the Greco-Turkish Treaty of Friendship of 1930 and took actions against the Greek minority.[42][43] | |

| 1971 | The Halki Theological College, the higher education component of the Halki seminary and the only school where the Greek minority in Turkey used to educate its clergymen, is closed by Turkish authorities. All private, religious or academic, Muslim and non Muslim, were closed that year.[131] | |

| 1971-74 | Oil is discovered in the north Aegean by the Greek island of Thasos.[132] The first major discovery since exploration started in the mid-1960s.[133] | |

| 1974 | 15 July | The Greek Junta sponsors the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état |

| 20 July – 18 August | Turkish invasion of Cyprus | |

| 1987 | 27–30 March | 1987 Aegean crisis brought both countries very close to war. |

| 1994 | 7 March | Greek Government declares May 19 as a day of remembrance of the (1914–1923) Genocide of Pontic Greeks.[134] |

| 1995 | 21 July | Greece ratified the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea [135] Turkey said the exercise of this treaty, if Greece expands its territorial waters to 12 nm, would be casus belli.[136] |

| 26 December | The Imia-Kardak crisis brought the two countries to the brink of war. | |

| 1997 | 5 January | Cyprus announces purchase of Russian-made surface-to-air missiles, starting Cyprus Missile Crisis. It would resolve in December 1998 when Greece purchased the missiles and positioned them in Crete. |

| 1999 | Abdullah Öcalan (Kurdish rebel leader), leaving the Greek embassy, is captured in Kenya and causes a crisis | |

| 2001 | 14 September | Greek Government declares September 14 as a "day of remembrance of the Genocide of the Hellenes of Asia Minor by the Turkish state".[134] |

See also

- History of Greece

- History of Turkey

- History of Cyprus

- Hellenoturkism

- Foreign relations of Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Northern Cyprus

- European Union–Turkey relations

- Greece–Turkey border

- Intermediate Region

- Greeks in Turkey

- Greeks in Middle East

- Turks in Greece

- Turks in Europe

Notes

References

- ^ Heraclides, Alexis (2012-03-01). "'What will become of us without barbarians?' The enduring Greek–Turkish rivalry as an identity-based conflict". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 12 (1): 115–134. doi:10.1080/14683857.2012.661944. ISSN 1468-3857. S2CID 143599413.

- ^ Bahcheli, Tozun (2021-09-23). Greek-Turkish Relations Since 1955. New York: Routledge. pp. 5–18. doi:10.4324/9780429040726. ISBN 978-0-429-04072-6.

- ^ Nation, R. Craig (2003). War in the Balkans, 1991-2002 : [comprehensive history of wars provoked by Yugoslav collapse : Balkan region in world politics, Slovenia and Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Greece, Turkey, Cyprus. Progressive Management]. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-5201-2165-9. OCLC 1146235450.

- ^ Blank, Stephen (1999). Mediterranean security into the coming millennium. Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. p. 267. OCLC 761402684.

- ^ Dokos, Thanos (2007). Greek security in the 21st century. Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). p. 21. ISBN 978-960-8356-20-7. OCLC 938611741.

- ^ "Issues of Greek - Turkish Relations - Hellenic Republic – Ministry of Foreign Affairs". www.mfa.gr. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ "From Rep. of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ Kapodistrias, Ioannis (1830). "Recognition and Establishment of Diplomatic and Consular Relations". Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "The Greek Embassy in Istanbul – Onassis Cavafy Archive". Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ Kelder, Jorrit (2004–2005). "The Chariots of Ahhiyawa". Dacia, Revue d'Archéologie et d'Histoire Ancienne (48–49): 151–160.

The Madduwatta text represents the first textual evidence for Greek incursions on the Anatolian mainland... Mycenaeans settled there already during LH IIB (around 1450 BC; Niemeier, 1998, 142).

- ^ Isiskal, Hüseyin (2002). "An Analysis of the Turkish-Greek Relations from Greek 'Self' and Turkish 'Other' Perspective: Causes of Antagonism and Preconditions for Better Relationships" (PDF). Turkish Journal of International Relations. 1: 118.

- ^ Dumberry, Patrick (2012). "Is Turkey the 'Continuing' State of the Ottoman Empire Under International Law?". Netherlands International Law Review. 59 (2): 235–262. doi:10.1017/s0165070x12000162. ISSN 0165-070X. S2CID 143692430.

- ^ Öktem, Emre (2011-08-05). "Turkey: Successor or Continuing State of the Ottoman Empire?". Leiden Journal of International Law. 24 (3): 561–583. doi:10.1017/s0922156511000252. ISSN 0922-1565. S2CID 145773201.

- ^ Stouraitis, Ioannis (2014-07-01). "Roman identity in Byzantium: a critical approach". Byzantinische Zeitschrift (in German). 107 (1): 176. doi:10.1515/bz-2014-0009. ISSN 1868-9027.

- ^ West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 829. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

The first people to use the ethnonym Turk to refer to themselves were the Turuk people of the Gokturk Khanate in the mid sixth-century

- ^ Qiang, Li; Kordosis, Stefanos (2018). "The Geopolitics on the Silk Road: Resurveying the Relationship of the Western Türks with Byzantium through Their Diplomatic Communications". Medieval Worlds. medieval worlds (Volume 8. 2018): 109–125. doi:10.1553/medievalworlds_no8_2018s109. ISSN 2412-3196.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Sinor, Dennis (1996). The First Türk Empire (553–682). pp. 327–332. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0. Retrieved 2022-01-23.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ The Turkic Languages. 2015. p. 25.

The name 'Seljuk is a political rather than ethnic name. It derives from Selčiik, born Toqaq Temir Yally, a war-lord (sil-baši), from the Qiniq tribal grouping of the Oghuz. Seljuk, in the rough and tumble of internal Oghuz politics, fled to Jand, c.985, after falling out with his overlord.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Mateos, Natalia Ribas. The Mediterranean in the Age of Globalization: Migration, Welfare & Borders. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412837750.

- ^ Petsalis-Diomidis, Nicholas. Greece at the Paris Peace Conference/1919. Inst. for Balkan Studies, 1978.

- ^ Grigoriadis, Ioannis N. (2011). "Redefining the Nation: Shifting Boundaries of the 'Other' in Greece and Turkey". Middle Eastern Studies. 47 (1): 175. doi:10.1080/00263206.2011.536632. hdl:11693/11995. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 27920347. S2CID 44340675.

- ^ Miller, William (1929). "Greece since the Return of Venizelos". Foreign Affairs. 7 (3): 470. doi:10.2307/20028707. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20028707.

- ^ Polyzoides, Adamantios T. (1928). "The Return of Venizelos to Power In Greece". Current History (1916-1940). 29 (3): 453. ISSN 2641-080X. JSTOR 45333045.

- ^ a b 100+2 Χρόνια Ελλάδα [100+2 Years of Greece]. Vol. A. I Maniateas Publishing Enterprises. 2002. pp. 208–209.

- ^ Mangoe, Andrew (1999). Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. John Murray. p. 487.

- ^ Barlas, Dilek (1998). Etatism and Diplomacy in Turkey: Economic and Foreign Policy Strategies in an Unknown World, 1929–39. Leiden: Brill. p. 188. ISBN 9004108556.

- ^ Featherstone, Kevin ...; et al. (2010). The last Ottomans: the Muslim minority of Greece, 1940–1949 (1. publ. ed.). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 63. ISBN 9780230232518.

- ^ Aktar, Ayhan (2006). Varlık vergisi ve "Türkleştirme" politikaları (in Turkish) (8. bs. ed.). İstanbul: İletişim. ISBN 9754707790.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1994). World Orders, Old And New. Pluto Press London.

- ^ Roberts, Geoffrey (2011). "Moscow's Cold War on the Periphery: Soviet Policy in Greece, Iran, and Turkey, 1943—8". Journal of Contemporary History. 46 (1): 78–81. doi:10.1177/0022009410383292. hdl:20.500.12323/1406. ISSN 0022-0094. S2CID 161542583.

- ^ Colibasanu, Antonia (2021-07-27). "Turkey's Strategy in the Eastern Med". Geopolitical Futures. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ Map based on map from the CIA publication Atlas: Issues in the Middle East, collected in Perry–Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas Libraries web cite.

- ^ Roucek, Joseph S. (1944). "The Legal Aspects of Sovereignty over the Dodecanese". American Journal of International Law. 38 (4): 704. doi:10.1017/s000293000015746x. ISSN 0002-9300. S2CID 235843284.

- ^ a b "Dodecanese Issue Revived by Turks; Greeks Scoff at New Claim to Some Aegean Islands". The New York Times. May 24, 1964.

- ^ Huth, Paul (2009). Standing Your Ground: Territorial Disputes and International Conflict. University of Michigan Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-472-02204-5.

From early 1950s onward Greece has favored union with Cyprus through a policy of enosis

- ^ "The Three-Mile Limit: Its Juridical Status". Valparaiso University Law Review. 6 (2): 170–184. 2011-06-03.

- ^ Papacosma, S. Victor. Legacy of strife : Greece, Turkey, and the Aegean. p. 303. OCLC 84602250.

- ^ "6–7 Eylül Olayları". Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- ^ Turkey and the West: From Neutrality to Commitment, p. 310, at Google Books

- ^ Yaman, Ilker (17 March 2014). "The Istanbul Pogrom". We Love Istanbul. We Love Istanbul.

- ^ Kuyucu, Ali Tuna (2005). "Ethno-religious 'unmixing' of 'Turkey': 6–7 September riots as a case in Turkish nationalism". Nations and Nationalism. 11 (3): 361–380. doi:10.1111/j.1354-5078.2005.00209.x.

- ^ a b "Turks Expelling Istanbul Greeks; Community's Plight Worsens During Cyprus Crisis". The New York Times. August 9, 1964.

- ^ a b Roudometof, Victor; Agadjanian, Alexander; Pankhurst, Jerry (2006). Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age: Tradition Faces the 21st Century. AltaMira Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-75910537-9.

- ^ "Why Turkey and Greece cannot reconcile". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ "Turkish Jets Violated Greek Airspace Over 2,000 Times Last Year [Infographic]". Forbes. 26 November 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Greek PM hits out at Turkey over air space 'violations'". Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ Sounak Mukhopadhyay (30 November 2015). "Russia Accuses Turkey Of Violating Greek Airspace A Day After Shooting Down Russian Jet". International Business Times. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Turkey violated Greek airspace more than 2,000 times last year". The Week UK. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Turkey buzzes weakened Greece". POLITICO. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ Squires, Nick (10 April 2018). "Greek soldiers fire warning shots at Turkish helicopter in Aegean Sea amid growing tensions". The telegraph. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs announcement on the statements by Turkeys leadership related to the Aegean (15 March 2019) – Announcements – Statements – Speeches". www.mfa.gr. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ "Greece condemns Erdogan's 'unacceptable' comments on airspace violations | Kathimerini". www.ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ "Turkey warns Greece over 'provocation' in Aegean". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Government says no evidence of violation of Greek territory". Ekathimerini. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Nation, R. Craig (2003). "Greece, Turkey, Cyprus". War in the Balkans, 1991-2002: 304.

- ^ "Greece-Turkey Aegean Disputes: A Short Retrospective on the ICJ Option" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|via=ignored (help) - ^ "BBC News | Europe | Greek ministers resign over Ocalan". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ Nation, R. Craig (2003). "Greece, Turkey, Cyprus". War in the Balkans, 1991-2002: 308.

- ^ Nation, R. Craig (2003). "Greece, Turkey, Cyprus". War in the Balkans, 1991-2002: 308–309.

- ^ "Erdogan: Turkey gave away Aegean islands in 1923". naftemporiki.

- ^ "Erdogan disputes Treaty of Lausanne, prompting response from Athens". ekathimerini.

- ^ "Turkish FM disputes Lausanne Treaty". ekathimerini.

- ^ "Erdogan's talk of 'kinsmen' in Thrace raises concerns in Greece". ekathimerini.

- ^ "CHP head slams Greek defense minister, vows to take back 18 islands 'occupied by Greece' in 2019". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ ""Greece should not test our patience" – Turkish opposition party". Ahval. 21 December 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Turkish defense minister sparks controversy, again | Kathimerini". www.ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ "Akar's remarks 'not based on reason,' Greek Defense Minister says | Kathimerini". www.ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ a b Sezer, Duygu Bazoglu (1999). "TURKISH SECURITY CHALLENGES IN THE 1990s". Mediterranean Security into the Coming Millennium: 263–279.

- ^ a b c Nation, R. Craig (2003). "Greece, Turkey, Cyprus". War in the Balkans, 1991-2002: 279–324.

- ^ "EU leaders approve sanctions on Turkish officials over gas drilling". The Guardian. 11 December 2020.

- ^ Gumrukcu, Michele Kambas, Tuvan (August 14, 2020). "Greek, Turkish warships in 'mini collision' Ankara calls provocative". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Turkey's Oruc Reis survey vessel back near southern shore, ship tracker shows". Reuters. 15 September 2020.

- ^ Oya Akgönenç, “A Precarious Peace in Bosnia-Herzegovina: The Dayton Accord and Its Prospect for Success,” in R. Craig Nation, ed., The Yugoslav Conflict and Its Implications for International Relations, Ravenna: Longo Editore, 1998, pp. 61–70.

- ^ a b c "Analysis: Greek Security Policy | In the Eastern Mediterranean". SETA. 2020-02-24. Retrieved 2022-04-07.

- ^ Carassava, Anthee (19 November 2007). "Greece and Turkey Open Gas Pipeline". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ^ a b "International – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ London, Ann M. Simmons in Moscow and Benoit Faucon in (2018-08-12). "Caspian Nations Move to Settle Dispute on Oil and Gas Reserves". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Reuters (2022-05-09). "Greece, UAE agree joint investments in energy, other sectors". Reuters. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "United Arab Emirates Natural Gas Reserves, Production and Consumption Statistics - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Gavra, Eleni; Bourlidou, Anastasia; Gkioufi, Klairi (2012). "Management of the Greek's ekistics and cultural heritage in Turkey". Louvain-la-Neuve: European Regional Science Association (ERSA).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Tension between Turkey, Greece flares up with row over genocide, Sümela". Hürriyet daily news.

- ^ Sitaropoulos, Nicholas (2004). "Freedom of Movement and the Right to a Nationality v. Ethnic Minorities: The Case of ex Article 19 of the Greek Nationality Code". European Journal of Migration and Law. 6 (3): 205–206. doi:10.1163/1571816043020011. ISSN 1388-364X.

- ^ a b Dayıoğlu, Ali; Aslım, İlksoy (2014-12-31). "Reciprocity Problem between Greece and Turkey: The Case of Muslim-Turkish and Greek Minorities". Athens Journal of History. 1 (1): 47. doi:10.30958/ajhis.1-1-3. ISSN 2407-9677.

- ^ "Hiç engel yok 24 saatte okul açılır". Radikal (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ^ DHA. "Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan: Tribünde seyirci değiliz". www.hurriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ^ "Asylum quarterly report – Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2019-07-26. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ^ Ahmet, İçduygu. Turkey's evolving migration policies : a Mediterranean transit stop at the doors of the EU. OCLC 1088484424.

- ^ a b c Benvenuti, Bianca (2017). The migration paradox and EU-Turkey relations. ISBN 978-88-9368-023-3. OCLC 1030914649.

- ^ "BBC NEWS – Europe – Landmine deaths on Greek border". 29 September 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "BBC News – EUROPE – Greece rescues immigrant ship". 5 November 2001. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Turkish coast guard caught escorting smugglers into Greece – report". The Sofia Echo. September 21, 2009.

- ^ "Turkey's Erdogan accuses Greece of Nazi tactics against migrants at border". reuters. 11 March 2020.

- ^ "Greece returns 2 Turkish soldiers at border – Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ^ "Video shows Hellenic Coast Guard vessel being harassed by Turkish one | Kathimerini". www.ekathimerini.com. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- ^ "Greece sees first mass arrival of migrant boats in three years, KAROLINA TAGARIS | Kathimerini". www.ekathimerini.com.

- ^ Ensor, Josie; Squires, Nick (August 30, 2019). "More than 600 refugees arrive on Lesbos in one day in record high since migrant crisis". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "As refugee numbers rise, Greece and Turkey face new border challenges | Thomas Seibert". AW.

- ^ "Turkey suspends generals linked to alleged coup plot". bbc. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "Turkey: Military chiefs resign en masse". BBC News. telegraph. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Factbox: What was Turkey's 'Sledgehammer' trial?". reuters. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "DHKP/C arrests in Greece coordinated by CIA, MİT, EYP". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Captured DHKP-C terrorists in Athens plotted attacking Erdoğan, Greek media says". Daily Sabah. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Arrested DHKP-C militants plotted to assassinate Erdoğan in Athens: Greek media". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Greek court rules to extradite suspected terrorist to Turkey – Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ^ "Greece harbors terrorist, including PKK, says Turkey". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ^ Christofis, Nikos; Baser, Bahar; Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi (2019-03-06). "The View from Next Door: Greek-Turkish Relations after the Coup Attempt in Turkey" (PDF). The International Spectator. 54 (2): 67–86. doi:10.1080/03932729.2019.1570758. ISSN 0393-2729. S2CID 159124051.

- ^ "995 Turks seek asylum in Greece". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Turkish FM: Military attaches in Athens have fled to Italy". naftemporiki. 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Statement about Turkish attaches brings Greek relief". kathimerini.

- ^ "Seven Turkish citizens seek asylum in Greece after coup bid". hurriyet.

- ^ "Seven Turkish citizens requesting asylum in Greece". ekathimerini.

- ^ "Turkish judge escapes to Greece on migrant boat, seeks asylum". hurriyet.

- ^ "Media report: Turkish judicial official requests asylum in Greece". naftemporiki. 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Turkish judicial official requests asylum on Greek island". ekathimerini.

- ^ "Turkish judge seeks asylum in Greece: news agency". reuters. 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Greek media say Turkish boat group sought asylum". www.aa.com.tr.

- ^ Stamouli, Stelios Bouras and Nektaria (September 21, 2016). "Greece Rejects Asylum Requests by Three Turkish Officers". Wall Street Journal – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ Stamouli, Nektaria (October 4, 2016). "More Turks Seek Asylum in Greece After Coup Attempt". Wall Street Journal – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ "Turkish commandos ask for asylum". kathimerini. 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Seventeen Turkish citizens seek sanctuary in Greece: Greek coastguard". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ "Turkey suspends 'migrant readmission' deal with Greece – Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ^ "NATO chief calls for 'calm' amid Turkey-Greece crisis – Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ^ "Sector group: Coup attempt in Turkey to negatively affect Greek tourism". naftemporiki. 8 January 2016.

- ^ Alexandris, Alexis (1980). Imbros and Tenedos:: A Study of Turkish Attitudes Toward Two Ethnic Greek Island Communities Since 1923 (PDF). Pella Publishing Company. p. 21.

- ^ Unidos), Helsinki Watch (Organización : Estados (1992). Denying human rights and ethnic identity : the Greeks of Turkey. ISBN 1-56432-056-1. OCLC 1088883463.

- ^ TIMES, Wireless to THE NEW YORK (1930-06-11). "GREECE AND TURKEY IN FRIENDSHIP PACT; Signing of Accord at Istanbul Ends 100 Years' Armed Enmity Between the Nations. MORE TREATIES TO FOLLOW Greece Agrees to Pay $2,125,000 Indemnity--Status Quo Is Recognized Under Pact. Turkish Press Hails Pact. Lauds Balkan Union Plan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ "ADDITIONAL TREATY TO THE TREATY OF FRIENDSHIP, NEUTRALITY, CONCILIATION AND ARBITRATION OF OCTOBER 30TH, 1930, AND TO THE PACT OF CORDIAL FRIENDSHIP OF SEPTEMBER 14TH, 1933, BETWEEN GREECE AND TURKEY. SIGNED AT ATHENS, APRIL 27TH, 1938" (PDF). 1938. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "On This Day: The unification of the Dodecanese islands with Greece". Greek Herald. 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ STUECK, WILLIAM (1986). "The Korean War as International History". Diplomatic History. 10 (4): 292. ISSN 0145-2096.

- ^ "Greece and Turkey join NATO (London, 22 October 1951)". CVCE.EU by UNI.LU. 2011-12-08. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ TOKTAS, SULE; ARAS, BULENT (2009). "The EU and Minority Rights in Turkey". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (4): 703. ISSN 0032-3195.

- ^ Proedrou, P.; Sidiropoulos, T. (1992). "Prinos Field--Greece Aegean Basin". 20: 275–291.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Times, Clyde H. Farnsworth Special to The New York (1974-07-23). "Greek‐Turkish Oil‐Field Dispute In Aegean Remains Unresolved". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ a b Bölükbasi, Deniz (2004-05-17). Turkey and Greece: The Aegean Disputes. Routledge-Cavendish. p. 62. ISBN 0-275-96533-3.

- ^ Strati, Anastasia (2000), Chircop, Aldo; Gerolymatos, André; Iatrides, John O. (eds.), "Greece and the Law of the Sea: A Greek Perspective", The Aegean Sea after the Cold War: Security and Law of the Sea Issues, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 89–102, doi:10.1007/978-1-137-08879-6_7, ISBN 978-1-137-08879-6, retrieved 2022-04-29

- ^ publisher., International Crisis Group. Turkey-Greece : from maritime brinkmanship to dialogue. OCLC 1255218774.

Further reading

- Turkish-Greek Relations: Escaping from the Security Dilemma in the Aegean. Routledge. 2004. ISBN 978-0-203-50191-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Bahcheli, Tozun (1987). Greek-Turkish Relations Since 1955. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-7235-6.

- Brewer, David (2003). The Greek War of Independence: The Struggle for Freedom from the Ottoman Oppression and the Birth of the Modern Greek Nation. Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-84511-504-3.

- Greek-Turkish Relations: In the Era of Globalization. Brassey's Inc. 2001. ISBN 1-57488-312-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Ker-Lindsay, James (2007). Crisis and Conciliation: A Year of Rapprochement between Greece and Turkey. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-504-3.

- Kinross, Patrick (2003). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-599-0.

- Smith, Michael L. (1999). Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor, 1919–1922. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08569-7.

External links

- Turkish PM on landmark Greek trip

- Greece-Turkey boundary study by Florida State University, College of Law

- Greece's Shifting Position on Turkish Accession to the EU Before and After Helsinki (1999)

- Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the relations with Greece

- Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the relations with Turkey