Serbia Strong: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Mrhumanwiki (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| cover = Serbia Strong.jpg |

| cover = Serbia Strong.jpg |

||

| alt = |

| alt = |

||

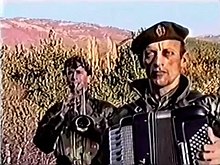

| caption = Still from the video showing an |

| caption = Still from the video showing an Novislav Djajic (right) and Nenad Tintor (left) playing the accordion and trumpet {{citation needed|date=December 2023}} |

||

| type = |

| type = |

||

| artist = Željko Grmuša |

| artist = Željko Grmuša |

||

Revision as of 15:56, 13 July 2024

| "Karadžić, Lead Your Serbs" | |

|---|---|

Still from the video showing an Novislav Djajic (right) and Nenad Tintor (left) playing the accordion and trumpet [citation needed] | |

| Song by Željko Grmuša | |

| Released | 1993 |

| Genre | Turbo-folk |

| Length | 3:38 |

Serbia Strong (Template:Lang-sr) is a nickname given to a Serb nationalist, anti-Croat and anti-Muslim propaganda music video[1] from the Yugoslav Wars.[2][3][4][5] The song has spread globally amongst far-right groups and the alt-right as a internet meme.[2][3][6]

The song was originally called "Karadžić, Lead Your Serbs" (Template:Lang-sr, pronounced [kâradʒitɕu ʋǒdi sr̩̂be sʋǒje]) in reference to the Bosnian Serb military leader and convicted war criminal Radovan Karadžić.[7] It is also known as "God Is a Serb and He Will Protect Us" (Template:Lang-sr, pronounced [bôːɡ je sr̩̂bin i ôːn tɕe nas tʃǔːʋati])[a] and "Remove Kebab".[2][3]

Background

At the peak of the inter-ethnic wars of the 1990s that broke up Yugoslavia, a song called "Karadžiću, vodi Srbe svoje" (Template:Lang-en) was recorded in 1993.[2][7] The song was composed as a morale boosting tune for Serbian forces during one of the wars.[7] In the video of the song, the tune is performed by four males in Serbian paramilitary uniforms at a location with hilly terrain in the background.[2] Footage of captured Muslim prisoners in wartime Serb-run internment camps are featured in a falsified[8] version of the video which is popular on the Internet.[9]

Parts of the tune attempt to instill a sense of foreboding in their opponents with lines such as "The wolves are coming – beware, Ustashe and Turks".[2][3][9] Derogatory terms are used in the song, such as "Ustaše" in reference to ultranationalist and fascist[10] Croat fighters and "Turks" for Bosniaks, with lyrics warning that Serbs, under the leadership of Radovan Karadžić, were coming for them.[2][3][5][9]

The song's content celebrates Serb fighters and the killing of Bosniaks and Croats along with wartime Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, who was on 24 March 2016 found guilty of genocide against Bosnian Muslims and crimes against humanity during the Bosnian War (part of the Yugoslav Wars).[2][9][11] Karadžić was convicted of "persecution, extermination, deportation, forcible transfer, and murder in connection with his campaign to drive Bosnian Muslims and Croats out of villages claimed by Serb forces".[12] On 20 March 2019, his appeal was rejected and his 40 year sentence was increased to life imprisonment.[13] During the Bosnian War, the song was a marching anthem for nationalist Serb paramilitaries (revived "Chetniks").[14]

The song has been rewritten multiple times in various languages and has retained its militant and anti-Bosnian themes.[2] "Remove Kebab" is the name for the song used by the alt-right and other ultranationalist groups.[5]

Internet popularity

Between 2006 and 2008, numerous edits of the video, originally made for the mockumentary TV show Četnovizija,[15][user-generated source] were posted on the Internet.[2] Throughout the 2000s, the video was parodied for its aggressively jingoistic nature.[16] Meanwhile, a Turkish internet user parodied the sentiment of Serbian nationalists online, with a satirical incoherent rant beginning with "remove kebab" and ending with the claim that Tupac is alive in Serbia.[17] Although the rant initially intended to parody racism, the origins were lost once it became a common phrase in alt-right discourse.[18]

The meme gained popularity amongst fans of Hearts of Iron IV and Europa Universalis IV, grand strategy computer games by Paradox Interactive,[16][19] where it referred to the player aiming to defeat the Ottoman Empire or other Islamic nations within these games.[16] The word "kebab" was eventually banned from Paradox Interactive's official forums due to frequent use by the alt-right and other ultranationalists.[19] Shortly after the Christchurch mosque shootings, the meme was also banned from Reddit communities based around Paradox Interactive games.[18] The meme also appeared in over 800 threads in the r/The_Donald subreddit.[4][20]

The song's popularity rose over time with radical elements of many right-wing groups within the West.[2][3] The song is far more famous in the rest of the world than in the Balkans.[21][22][23] Novislav Đajić, the song's alleged accordion player, has since become a widespread 4chan meme and is called "Dat Face Soldier" or the image itself as "Remove Kebab".[2][3][4][24][20] Đajić had been convicted in Germany for his part in the murder of 14 people during the war, resulting in 5 years imprisonment and deportation to another country following his jail sentence in 1997.[2]

Academic research found that in a dataset obtained by scraping Know Your Meme in 2018, "Remove Kebab" constituted 1 of every 200 entries per community in a data set sampled for political memes.[25] "Remove Kebab" was particularly common on Gab, an alt-tech social media platform known for its far-right userbase.[25]

Christchurch mosque shootings

Brenton Harrison Tarrant, the Australian gunman in the Christchurch mosque shootings, had the phrase "Remove Kebab" written on one of his weapons.[2] In his manifesto The Great Replacement (named after a far-right theory of the same name by French writer Renaud Camus), he describes himself as a "part-time kebab removalist".[3][24] He also livestreamed himself playing the song in his car minutes before the shooting.[2][5][26][27]

Following the shootings, various videos of the song were removed from YouTube, including some with over a million views. Users quickly re-uploaded the tune, saying it was to "protest censorship".[28] In an interview following the shooting, the main singer of the song, Željko Grmuša, said, "It is terrible what that guy did in New Zealand, of course I condemn that act. I feel sorry for all those innocent people. But he started killing and he would do that no matter what song he listened to."[7][21]

Notes

References

- ^ Doyle, Gerry (15 March 2019). "New Zealand mosque attacker's plan began and ended online". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Coalson, Robert (15 March 2019). "Christchurch Attacks: Suspect Took Inspiration From Former Yugoslavia's Ethnically Fueled Wars". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Mosque shooter brandished material glorifying Serb nationalism". Al Jazeera English. 15 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Ward, Justin (19 April 2018). "Day of the trope: White nationalist memes thrive on Reddit's r/The_Donald". splcenter.org. Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Schindler, John R. (20 March 2019). "Ghosts of the Balkan wars are returning in unlikely places". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Hemmer, Nicole (2 December 2016). "Tweedy racists and "ironic" anti-Semites: the alt-right fits a historical pattern". Vox. Archived from the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Nestorović, V. (16 March 2019). "Željko objasnio kako je zaista nastala njegova pesma uz koju je Tarant počinio pokolj na Novom Zelandu!". alo.rs (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Oğuz, Renan Furkan (9 October 2020). "The Internet's Winding Roads to White Supremacy". Arc Digital. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d Gambrell, Jon (15 March 2019). "Mosque shooter brandished white supremacist iconography". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945 : occupation and collaboration. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3615-4. OCLC 45820953.

- ^ Halilovich, Hariz (19 March 2019). "Long-Distance Hatred: How the NZ Massacre Echoed Balkan War Crimes". Transitions Online. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (24 March 2016). "Radovan Karadzic, a Bosnian Serb, Gets 40 Years Over Genocide and War Crimes". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "UN appeals court increases Radovan Karadzic's sentence to life imprisonment". Associated Press. 20 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "New Zealand mosque shooting: What is known about the suspects?". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Karadzicu, vodi Srbe svoje (Video 1995) - IMDb

- ^ a b c Katz, Jonty (13 March 2017). "Video games of the alt-right". Honi Soit. University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "Serbia Strong / Remove Kebab". Know Your Meme. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ a b Khan, Rumi (6 July 2019). "The Alt-Right as Counterculture: Memes, Video Games and Violence". Harvard Political Review. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ a b Winkie, Luke (6 June 2018). "The Struggle Over Gamers Who Use Mods To Create Racist Alternate Histories". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ a b Sixsmith, Ben (15 March 2019). "Guns Internet Life Media: The dark extremism of the 'extremely online'". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Autor pjesme koju je napadač slušao prije pokolja: "Kakve veze pjesma ima s terorističkim napadom?"". Dnevnik.hr (in Croatian). 16 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Autor četničkog pjesmuljka kojeg je Tarrant slušao prije masakra živi kod Knina: Naravno da se osjećam ugroženo". hrvatska-danas.com (in Croatian). 16 March 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Zašto je ubica slušao krajišku pesmu pre masakra? Šta se krije iza pokreta "Remove kebab", koji poziva i na ubijanje muslimana (VIDEO)". telegraf.rs (in Croatian). 16 March 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ a b Weill, Kelly; Sommer, Will (15 March 2019). "Mosque Attack Video Linked to 'White Genocide' Rant". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ a b Zannettou, Savvas; Caulfield, Tristan; Blackburn, Jeremy; De Cristofaro, Emiliano; Sirivianos, Michael; Stringhini, Gianluca; Suarez-Tangil, Guillermo (31 October 2018). On the origins of memes by means of fringe web communities (PDF). ACM. pp. 5, 9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Koziol, Michael (15 March 2019). "Christchurch shooter's manifesto reveals an obsession with white supremacy over Muslims". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Zivanovic, Maja (15 March 2019). "New Zealand Mosque Gunman 'Inspired by Balkan Nationalists'". BalkanInsight. Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Covucci, David (18 March 2019). "YouTubers keep uploading racist meme anthem played by New Zealand shooter". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

External links

- Serbia Strong/Remove Kebab entry at Know Your Meme

- 1993 songs

- 2010s fads and trends

- /pol/ phenomena

- Anti-Bosniak sentiment

- Anti-Croat sentiment

- Bosnian War

- Christchurch mosque shootings

- Ethnic and religious slurs

- Internet memes

- Islam-related slurs

- Serbian nationalism

- Serbian patriotic songs

- White nationalist symbols

- Yugoslav Wars

- Cultural depictions of Radovan Karadžić

- Islamophobia in Serbia