Abbas Kiarostami: Difference between revisions

ScarletBrow (talk | contribs) →1990s: removed link to non-existing page "Hossein Sabzain" and a lone word "miranda" |

had lack of spiderman |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Redirect|Peter Parker}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{About|the superhero}} |

|||

{{Infobox person |

|||

{{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}} |

|||

| name = عباس کیارستمی<br/>Abbās Kiyārostamī |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

| image = Abbas-kiarostami-venice.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox comics character |

|||

| image_size =100px |

|||

<!--Wikipedia:WikiProject Comics--> |

|||

| caption = Kiarostami at the 65th Venice Film Festival, 2008 |

|||

| image = Spider-Man.jpg |

|||

| birth_name = |

|||

| imagesize = |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date and age|df=yes|1940|06|22}} |

|||

| converted=y |

|||

| birth_place = [[Tehran]], [[Iran]] |

|||

| caption = From ''[[The Amazing Spider-Man]]'' #547 (March 2008)<br />Art by [[Steve McNiven]] and [[Dexter Vines]] |

|||

| occupation = Director, screenwriter, producer |

|||

| publisher = [[Marvel Comics]] |

|||

| years_active = 1962–present |

|||

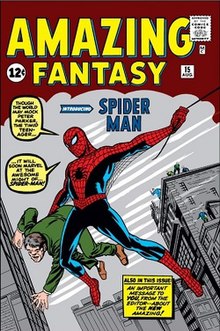

| debut = ''[[Amazing Fantasy]]'' #15 (Aug. 1962) |

|||

| creators = [[Stan Lee]], [[Steve Ditko]] |

|||

| alter_ego = |

|||

| real_name = Peter Benjamin Parker |

|||

| species = [[mutate (comics)|Human Mutate]] |

|||

| alliances = [[Daily Bugle]]<br/>Front Line<br/>[[Fantastic Four|New Fantastic Four]]<br/>[[Avengers (comics)|Avengers]]<br/>[[The New Avengers (comics)|New Avengers]]<br/>[[Future Foundation]]<br/>[[Heroes for Hire]] |

|||

| partners = [[Venom (comics)|Venom]]<br/>[[Ben Reilly|Scarlet Spider]]<br/>[[Wolverine (comics)|Wolverine]]<br/>[[Human Torch]]<br/>[[Daredevil (Marvel Comics)|Daredevil]]<br/>[[Black Cat (comics)|Black Cat]]<br/>[[Punisher]]<br/>[[Toxin (comics)|Toxin]]<br/> [[Iron Man]]<br/>[[Ms. Marvel]] |

|||

| supports = <!-- optional --> |

|||

| aliases = [[Ricochet (comics)|Ricochet]], [[Dusk (comics)|Dusk]], [[Prodigy (comics)|Prodigy]], [[Hornet (comics)|Hornet]], [[Ben Reilly]]/[[Scarlet Spider]] |

|||

| powers = *[[Superhuman strength]], [[Speedster (fiction)|speed]], agility, and [[Superhuman durability|endurance]] |

|||

*[[Healing factor]] |

|||

*Ability to cling to most surfaces |

|||

*Able to shoot extremely strong spider-web strings from wrists |

|||

*[[Precognition|Precognitive]] Spider-Sense |

|||

*Genius-level intellect |

|||

*Master hand-to-hand combatant |

|||

| cat = super |

|||

| subcat = Marvel Comics |

|||

| hero = y |

|||

| villain = |

|||

| sortkey = Spider-Man |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Spider-Man''' ('''Peter Parker''') is a [[Character (arts)|fictional character]], a [[Marvel Comics]] [[superhero]] created by writer-editor [[Stan Lee]] and writer-artist [[Steve Ditko]]. He [[first appearance|first appeared]] in ''[[Amazing Fantasy]]'' #15 (August 1962). Lee and Ditko conceived of the character as an orphan being raised by his [[Aunt May]] and [[Uncle Ben]], and as a [[teenager]], having to deal with the normal struggles of adolescence in addition to those of a costumed crime fighter. Spider-Man's creators gave him super strength and agility, the ability to cling to most surfaces, shoot spider-webs using devices of his own invention which he called "web-shooters", and react to danger quickly with his "spider-sense", enabling him to combat his foes. |

|||

'''Abbas Kiarostami''' ({{lang-fa| عباس کیارستمی }} ''Abbās Kiyārostamī''; born 22 June 1940) is an internationally acclaimed [[Iran]]ian [[film director]], [[screenwriter]], [[photographer]] and [[film producer]].<ref name="GuardianRanking">{{Cite news |

|||

| url = http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2003/nov/14/1 |

|||

| title = The world's 40 best directors |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2006 |

|||

| author = Panel of critics |

|||

| publisher = Guardian Unlimited |

|||

| location=London |

|||

| date=2003-11-14}}</ref><ref name="WexnerAK">{{Cite web |

|||

| url =http://wexarts.org/info/press/db/87_nr-kiarostami_elec.pdf |

|||

|format=PDF | title = Abbas Kiarostami Films Featured at Wexner Center |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2002 |

|||

| author = Karen Simonian |

|||

| publisher = Wexner center for the art |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="BFIpoll">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/63/ |

|||

| title = 2002 Ranking for Film Directors |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2002 |

|||

| publisher = British Film Institute |

|||

}}</ref> An active filmmaker since 1970, Kiarostami has been involved in over forty films, including [[short film|shorts]] and [[Documentary film|documentaries]]. Kiarostami attained critical acclaim for directing the ''[[Koker Trilogy]]'' (1987–94), ''[[Taste of Cherry]]'' (1997), and ''[[The Wind Will Carry Us]]'' (1999). |

|||

When Spider-Man first appeared in the early 1960s, teenagers in superhero comic books were usually relegated to the role of [[sidekick]] to the protagonist. The Spider-Man series broke ground by featuring Peter Parker, a teenage high school student and person behind Spider-Man's [[secret identity]] to whose "self-obsessions with rejection, inadequacy, and loneliness" young readers could relate.<ref name="Wright">{{Cite book|author=Wright, Bradford W.|title=Comic Book Nation|year=2001|publisher=Johns Hopkins Press : Baltimore|isbn=0801874505}}</ref> Unlike previous teen heroes such as [[Bucky]] and [[Dick Grayson|Robin]], Spider-Man did not benefit from being the protégé of any adult superhero mentors like [[Captain America]] and [[Batman]], and thus had to learn for himself that "with great power there must also come great responsibility"—a line included in a text box in the final panel of the first Spider-Man story, but later [[retcon|retroactively attributed]] to his guardian, the late Uncle Ben. |

|||

Kiarostami has worked extensively as a [[screenplay|screenwriter]], [[film editing|film editor]], [[art director]] and producer and has designed credit titles and publicity material. He is also a poet, [[photographer]], [[Painting|painter]], [[illustrator]], and [[graphic designer]]. He is part of a generation of filmmakers in the [[Iranian New Wave]], a [[Cinema of Iran|Persian cinema]] movement that started in the late 1960s and includes pioneering directors such as [[Forough Farrokhzad]], [[Sohrab Shahid Saless]], [[Mohsen Makhmalbaf]], [[Bahram Beizai]], and [[Parviz Kimiavi]]. These filmmakers share many common techniques including the use of poetic dialogue and allegorical storytelling dealing with political and philosophical issues.<ref name="Princeton">{{Cite web |

|||

| url =http://etc.princeton.edu/films/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogsection&id=8&Itemid=2 |

|||

| title =Abbas Kiarostami |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2007 |

|||

| author = Ivone Margulies |

|||

| publisher =Princeton University |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Marvel has featured Spider-Man in several [[List of Spider-Man titles|comic book series]], the first and longest-lasting of which is titled ''[[The Amazing Spider-Man]]''. Over the years, the Peter Parker character has developed from shy, nerdy high school student to troubled but outgoing college student, to married high school teacher to, in the late 2000s, a single freelance photographer, his most typical adult role. As of 2011, he is additionally a member of the [[Avengers (comics)|Avengers]] and the [[Fantastic Four]], Marvel's flagship superhero teams. In the comics, Spider-Man is often referred to as "Spidey", "web-slinger", "wall-crawler", or "web-head". |

|||

Kiarostami has a reputation for using child protagonists, for documentary style narrative films,<ref name="FirouzanFilmBio">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.firouzanfilms.com/HallOfFame/Inductees/AbbasKiarostami.html |

|||

| title = Abbas Kiarostami Biography |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2004 |

|||

| author = |

|||

| publisher = Firouzan Film |

|||

}}</ref> for stories that take place in rural villages, and for conversations that unfold inside cars, using stationary mounted cameras. He is also known for his use of contemporary [[Persian literature|Iranian poetry]] in the dialogue, titles, and themes of his films. |

|||

Spider-Man is one of the most popular and commercially successful superheroes.<ref>{{cite news|title=Why Spider-Man is popular.|url=http://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/story?id=101230&page=1|accessdate=18 November 2010}}</ref> As Marvel's flagship character and company mascot, he has appeared in many forms of media, including several animated and live-action [[Spider-Man television series|television shows]], [[Print syndication|syndicated]] newspaper [[The Amazing Spider-Man#Newspaper comic strip|comic strips]], and a [[Spider-Man in film|series of films]] starring [[Tobey Maguire]] as the "friendly neighborhood" hero in the first three movies. [[Andrew Garfield]] will take over the role of Spider-Man in a [[The Amazing Spider-Man (2012 film)|planned reboot of the films]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.comingsoon.net/news/movienews.php?id=67468 |title=It's Official! Andrew Garfield to Play Spider-Man! |publisher=Comingsoon.net |date=2010-07-02 |accessdate=2010-10-09}}</ref> [[Reeve Carney]] stars as Spider-Man in the 2010 [[Broadway musical]] ''[[Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark]]''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.broadway.com/shows/spider-man-turn-off-the-dark/buzz/153279/complete-cast-announced-for-spider-man-turn-off-the-dark/ |title=Complete Cast Announced for Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark |publisher=Broadway.com |date=2010-08-16 |accessdate=2010-10-09}}</ref> Spider-Man placed 3rd on IGN's Top 100 Comic Book Heroes of All Time in 2011.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ign.com/top/comic-book-heroes/3|title=IGN's Top 100 Comic Book Heroes|accessdate=2011-05-09}}</ref> |

|||

==Early life and background== |

|||

[[Image:UT honarhaye ziba.jpg|thumb|right|Kiarostami majored in painting and graphic design at the [[Tehran University]] College of [[Fine art|Fine Arts]]]] |

|||

Kiarostami was born in [[Tehran]]. His first artistic experience was painting, which he continued into his late teens, winning a painting competition at the age of eighteen shortly before he left home to study at the [[Tehran University]] School of Fine Arts.<ref name="AKzeitgeit"/> There he majored in painting and graphic design, and supported his degree by working as a traffic policeman. As a painter, designer, and illustrator, Kiarostami worked in advertising in the 1960s, designing [[poster]]s and creating commercials. Between 1962 and 1966, he shot around 150 advertisements for Iranian television. Towards the late 1960s, he began creating credit titles for films (including ''[[Qeysar (film)|Gheysar]]'' by [[Masoud Kimiai]]) and illustrating children's books.<ref name="AKzeitgeit"/><ref name="AKOpenDemocracy">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.opendemocracy.net/arts-Film/article_815.jsp |

|||

| title = 10 x Ten: Kiarostami’s journey |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2002 |

|||

| author = Ed Hayes |

|||

| publisher = Open Democracy |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

==Publication history== |

|||

In 1969, Abbas married Parvin Amir-Gholi but later divorced her in 1982; they had two sons, Ahmad (born 1971) and Bahman (1978). At the age of fifteen, [[Bahman Kiarostami]] became a director and cinematographer by directing a documentary ''[[Journey to the Land of the Traveller]]'' in 1993. |

|||

===Creation and development=== |

|||

[[File:Spider Strikes v1n1 i05 Wentworth.png|thumb|right|Richard Wentworth a.k.a. the [[Spider (pulp fiction)|Spider]] in the pulp magazine ''The Spider''. Stan Lee stated that it was the name of this character that inspired him to create a character that would become Spider-Man.<ref name="LeeMair"/>]] |

|||

In 1962, with the success of the [[Fantastic Four]], Marvel Comics editor and head writer [[Stan Lee]] was casting about for a new superhero idea. He said the idea for Spider-Man arose from a surge in teenage demand for comic books, and the desire to create a character with whom teens could identify.<ref name="DeFalco" />{{rp|1}} In his autobiography, Lee cites the non-superhuman [[pulp magazine]] crime fighter the [[Spider (pulp fiction)|Spider]] (see also [[The Spider's Web]] and [[The Spider Returns]]) as a great influence,<ref name="LeeMair">{{Cite book|author=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]]; Mair, George|title=Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee|publisher=Fireside|year=2002|isbn=0-684-87305-2}}</ref>{{rp|130}} and in a multitude of print and video interviews, Lee stated he was further inspired by seeing a [[spider]] climb up a wall—adding in his autobiography that he has told that story so often he has become unsure of whether or not this is true.<ref group="note">{{Cite book|author=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]]; Mair, George|title=Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee|publisher=Fireside|year=2002|isbn=0-684-87305-2|quote=He goes further in his biography, claiming that even while pitching the concept to publisher Martin Goodman, "I can't remember if that was literally true or not, but I thought it would lend a big color to my pitch."}}</ref> Looking back on the creation of Spider-Man, 1990s Marvel editor-in-chief [[Tom DeFalco]] stated he did not believe that Spider-Man would have been given a chance in today's comics world, where new characters are vetted with test audiences and marketers.<ref name="DeFalco">{{Cite book|author=[[Tom DeFalco|DeFalco, Tom]]; [[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]]|editor=O'Neill, Cynthia|title=Spider-Man: The Ultimate Guide|publisher=[[Dorling Kindersley]]|location=New York|isbn=078947946X|year=2001}}</ref>{{rp|9}} At that time, however, Lee had to get only the consent of Marvel publisher [[Martin Goodman (publisher)|Martin Goodman]] for the character's approval.<ref name="DeFalco" />{{rp|9}} In a 1986 interview, Lee described in detail his arguments to overcome Goodman's objections.<ref group="note">''[[Detroit Free Press]]'' interview with Stan Lee, quoted in ''The Steve Ditko Reader'' by [[Greg Theakston]] (Pure Imagination, Brooklyn, NY; ISBN 1-56685-011-8), p. 12 (unnumbered). "He gave me 1,000 reasons why Spider-Man would never work. Nobody likes spiders; it sounds too much like Superman; and how could a teenager be a superhero? Then I told him I wanted the character to be a very human guy, someone who makes mistakes, who worries, who gets acne, has trouble with his girlfriend, things like that. [Goodman replied,] 'He's a hero! He's not an average man!' I said, 'No, we make him an average man who happens to have super powers, that's what will make him good.' He told me I was crazy".</ref> Goodman eventually agreed to let Lee try out Spider-Man in the upcoming final issue of the canceled science-fiction and supernatural anthology series ''Amazing Adult Fantasy,'' which was renamed ''[[Amazing Fantasy]]'' for that single issue, #15 (Aug. 1962).<ref name="Daniels">{{Cite book|author=Daniels, Les|authorlink=Les Daniels|title=Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics|publisher=Harry N. Abrams|location= New York|year=1991|isbn=0-8109-3821-9}}</ref>{{rp|95}} |

|||

<!--add in info about approving the character --> |

|||

Comics historian [[Greg Theakston]] says that Lee, after receiving Goodman's approval for the name Spider-Man and the "ordinary teen" concept, approached artist [[Jack Kirby]]. Kirby told Lee about an unpublished character on which he collaborated with [[Joe Simon]] in the 1950s, in which an orphaned boy living with an old couple finds a magic ring that granted him superhuman powers. Lee and Kirby "immediately sat down for a story conference" and Lee afterward directed Kirby to flesh out the character and draw some pages. Steve Ditko would be the inker.<ref group="note">{{Cite book|author=Ditko, Steve|authorlink=Steve Ditko|title=Alter Ego: The Comic Book Artist Collection|editor=Roy Thomas|publisher=[[TwoMorrows Publishing]]|year= 2000|isbn=1893905063|editor-link= Roy Thomas}} "'Stan said a new Marvel hero would be introduced in #15 [of what became titled ''Amazing Fantasy'']. He would be called Spider-Man. Jack would do the penciling and I was to ink the character.' At this point still, 'Stan said Spider-Man would be a teenager with a magic ring which could transform him into an adult hero—Spider-Man. I said it sounded like the [[Fly (Red Circle Comics)|Fly]], which Joe Simon had done for [[Archie Comics]]. Stan called Jack about it but I don't know what was discussed. I never talked to Jack about Spider-Man... Later, at some point, I was given the job of drawing Spider-Man'".</ref> When Kirby showed Lee the first six pages, Lee recalled, "I ''hated'' the way he was doing it! Not that he did it badly—it just wasn't the character I wanted; it was too heroic".<ref name="Theakston">{{Cite book|author=Theakston, Greg|title=The Steve Ditko Reader|publisher=Pure Imagination|location=Brooklyn, NY|year=2002|isbn=1-56685-011-8}}</ref>{{rp|12}} Lee turned to Ditko, who developed a visual style Lee found satisfactory. Ditko recalled: |

|||

Kiarostami was one of the few directors who remained in Iran after the [[Iranian revolution|1979 revolution]], when many of his colleagues fled to the west, and he believes that it was one of the most important decisions of his career. He has stated that his permanent base in Iran and his national identity have consolidated his ability as a filmmaker: |

|||

{{blockquote|One of the first things I did was to work up a costume. A vital, visual part of the character. I had to know how he looked ... before I did any breakdowns. For example: A clinging power so he wouldn't have hard shoes or boots, a hidden wrist-shooter versus a web gun and holster, etc. ... I wasn't sure Stan would like the idea of covering the character's face but I did it because it hid an obviously boyish face. It would also add mystery to the character....<ref name="ditko-history"/>}} Although the interior artwork was by Ditko alone, Lee rejected Ditko's cover art and commissioned Kirby to pencil a cover that Ditko inked.<ref name=gcd-af>[http://www.comics.org/series/1514/ ''Amazing Fantasy''] at the Grand Comics Database</ref> As Lee explained in 2010, "I think I had Jack sketch out a cover for it because I always had a lot of confidence in Jack's covers."<ref>{{cite news|url=https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=explorer&chrome=true&srcid=0B_lZovnpi13JNWQ5MDJmOTgtZDMzYy00MzI3LTllYjctNmM0ZWE4NjgyOWEx&hl=en_US | title= Deposition of Stan Lee|publisher = United States District Court, Southern District of New York: "Marvel Worldwide, Inc., et al., vs. Lisa R. Kirby, et al."| page= 37|location = [[Los Angeles]], [[California]]|date=December 8, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>When you take a tree that is rooted in the ground, and transfer it from one place to another, the tree will no longer bear fruit. And if it does, the fruit will not be as good as it was in its original place. This is a rule of nature. I think if I had left my country, I would be the same as the tree.-''Abbas Kiarostami''<ref name="GuardianLanscapes">{{Cite news |

|||

| url =http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2005/apr/16/art |

|||

| title =Landscapes of the mind |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-28 |

|||

| author = |

|||

| publisher =Guardian Unlimited |

|||

| location=London |

|||

| first=Stuart |

|||

| last=Jeffries |

|||

| date=2005-11-29}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

In an early recollection of the character's creation, Ditko described his and Lee's contributions in a mail interview with Gary Martin published in ''Comic Fan'' #2 (Summer 1965): "Stan Lee thought the name up. I did costume, web gimmick on wrist & spider signal."<ref>{{cite web|author=Ditko, Steve; Martin, Gary|year=1965|url=http://www.ditko.comics.org/ditko/artist/arcomicf.html|title= Steve Ditko - A Portrait of the Master|work=Comic Fan #2, Summer 1965|accessdate=2008-04-03}}{{Dead link|date=July 2010}}</ref> At the time, Ditko shared a Manhattan studio with noted [[Sexual fetishism|fetish]] artist [[Eric Stanton]], an art-school classmate who, in a 1988 interview with Theakston, recalled that although his contribution to Spider-Man was "almost nil", he and Ditko had "worked on storyboards together and I added a few ideas. But the whole thing was created by Steve on his own... I think I added the business about the webs coming out of his hands".<ref name="Theakston" />{{rp|14}} |

|||

Kiarostami frequently appears wearing dark-lensed spectacles or sunglasses. He wears them for medical reasons due to a [[Photophobia |sensitivity to light]].<ref name="Glasses">{{Cite web |

|||

| url =http://www.iranian.com/Books/2006/September/Memoir/index.html |

|||

| title =Besides censorship |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-27 |

|||

| year = 2006 |

|||

| author = Ari Siletz |

|||

| publisher =Iranian.com |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Kirby disputed Lee's version of the story, and claimed Lee had minimal involvement in the character's creation. According to Kirby, the idea for Spider-Man had originated with Kirby and [[Joe Simon]], who in the 1950s had developed a character called The Silver Spider for the [[Crestwood Publications|Crestwood]] comic ''Black Magic,'' who was subsequently not used.<ref group="note">Jack Kirby in "Shop Talk: Jack Kirby", ''[[Will Eisner]]'s [[The Spirit|Spirit]] Magazine'' #39 (February 1982): "Spider-Man was discussed between [[Joe Simon]] and myself. It was the last thing Joe and I had discussed. We had a strip called 'The Silver Spider.' The Silver Spider was going into a magazine called ''Black Magic.'' ''Black Magic'' folded with [[Crestwood Publications|Crestwood]] (Simon & Kirby's 1950s comics company) and we were left with the script. I believe I said this could become a thing called Spider-Man, see, a superhero character. I had a lot of faith in the superhero character that they could be brought back... and I said Spider-Man would be a fine character to start with. But Joe had already moved on. So the idea was already there when I talked to Stan".</ref> Simon, in his 1990 autobiography, disputed Kirby's account, asserting that ''Black Magic'' was not a factor, and that he (Simon) devised the name "Spider-Man" (later changed to "The Silver Spider"), while Kirby outlined the character's story and powers. Simon later elaborated that his and Kirby's character conception became the basis for Simon's [[Archie Comics]] superhero the [[Fly (Red Circle Comics)|Fly]]. Artist [[Steve Ditko]] stated that Lee liked the name [[Hawkman]] from [[DC Comics]], and that "Spider-Man" was an outgrowth of that interest.<ref name="ditko-history">{{Cite book|author=Ditko, Steve|authorlink=Steve Ditko|title=Alter Ego: The Comic Book Artist Collection|editor=Roy Thomas|publisher=[[TwoMorrows Publishing]]|year= 2000|isbn=1893905063|editor-link= Roy Thomas}}</ref> The hyphen was included in the character's name to avoid confusion with DC Comics' [[Superman]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thehotspotonline.com/blahblah/articles/spidy.htm |title=Spider-Man: The Birth of an Icon |publisher=thehotspotonline.com |date= |accessdate=2010-04-10}}</ref> |

|||

In 2000, at the [[San Francisco Film Festival]] award ceremony, Kiarostami surprised everyone by giving away his [[Akira Kurosawa|Akira Kurosawa Prize]] for lifetime achievement in directing to veteran Iranian actor [[Behrooz Vossoughi]] for his contribution to Iranian Cinema.<ref name="Firouzan">{{Cite web |

|||

| url =http://www.firouzanfilms.com/Reviews/BookReviews/AriSiletz_NotQuiteAMemoir.html |

|||

| title = Not Quite a Memoire |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Judy Stone | publisher = Firouzan Films |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="SC">{{Cite web |

|||

| url =http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/festivals/00/7/sfiff.html |

|||

| title = 43rd Annual San Francisco International Film Festival |

|||

| year = 2000 |

|||

| author = Jeff Lambert |

|||

| publisher = Sense of Cinema |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Simon concurred that Kirby had shown the original Spider-Man version to Lee, who liked the idea and assigned Kirby to draw sample pages of the new character but disliked the results—in Simon's description, "[[Captain America]] with cobwebs".<ref group="note">Simon, Joe, with Jim Simon. ''The Comic Book Makers'' (Crestwood/II, 1990) ISBN 1-887591-35-4. "There were a few holes in Jack's never-dependable memory. For instance, there was no ''Black Magic'' involved at all. ... Jack brought in the Spider-Man logo that I had loaned to him before we changed the name to The Silver Spider. Kirby laid out the story to Lee about the kid who finds a ring in a spiderweb, gets his powers from the ring, and goes forth to fight crime armed with The Silver Spider's old web-spinning pistol. Stan Lee said, 'Perfect, just what I want.' After obtaining permission from publisher [[Martin Goodman (publisher)|Martin Goodman]], Lee told Kirby to pencil-up an origin story. Kirby... using parts of an old rejected superhero named Night Fighter... revamped the old Silver Spider script, including revisions suggested by Lee. But when Kirby showed Lee the sample pages, it was Lee's turn to gripe. He had been expecting a skinny young kid who is transformed into a skinny young kid with spider powers. Kirby had him turn into... Captain America with cobwebs. He turned Spider-Man over to Steve Ditko, who... ignored Kirby's pages, tossed the character's magic ring, web-pistol and goggles... and completely redesigned Spider-Man's costume and equipment. In this life, he became high-school student Peter Parker, who gets his spider powers after being bitten by a radioactive spider. ... Lastly, the Spider-Man logo was redone and a dashing hyphen added".</ref> Writer [[Mark Evanier]] notes that Lee's reasoning that Kirby's character was too heroic seems unlikely—Kirby still drew the covers for ''Amazing Fantasy'' #15 and the first issue of ''The Amazing Spider-Man''. Evanier also disputes Kirby's given reason that he was "too busy" to also draw Spider-Man in addition to his other duties since Kirby was, said Evanier, "always busy".<ref name="Evanier">{{Cite book|author=[[Mark Evanier|Evanier, Mark]]; [[Neil Gaiman|Gaiman, Neil]]|year=2008|title=Kirby: King of Comics|publisher=Abrams|location=|isbn=081099447X}}</ref>{{rp|127}} Neither Lee's nor Kirby's explanation explains why key story elements like the magic ring were dropped; Evanier states that the most plausible explanation for the sudden change was that Goodman, or one of his assistants, decided that Spider-Man as drawn and envisioned by Kirby was too similar to the Fly.<ref name="Evanier" />{{rp|127}} |

|||

==Film career== |

|||

Author and Ditko scholar Blake Bell writes that it was Ditko who noted the similarities to the Fly. Ditko recalled that, "Stan called Jack about the Fly", adding that "[d]ays later, Stan told me I would be penciling the story panel breakdowns from Stan's synopsis". It was at this point that the nature of the strip changed. "Out went the magic ring, adult Spider-Man and whatever legend ideas that Spider-Man story would have contained". Lee gave Ditko the premise of a teenager bitten by a spider and developing powers, a premise Ditko would expand upon to the point he became what Bell describes as "the first [[work for hire]] artist of his generation to create and control the narrative arc of his series". On the issue of the initial creation, Ditko states, "I still don't know whose idea was Spider-Man".<ref>Bell, Blake. ''Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko'' (2008). Fantagraphic Books.p.54-57.</ref> Kirby noted in a 1971 interview that it was Ditko who "got ''Spider-Man'' to roll, and the thing caught on because of what he did".<ref>Skelly, Tim. "Interview II: 'I created an army of characters, and now my connection to them is lost.'" (Initially broadcast over WNUR-FM on "The Great Electric Bird," May 14, 1971. Transcribed and published in ''The Nostalgia Journal'' #27.) Reprinted in ''The Comics Journal Library Volume One: Jack Kirby'', George, Milo ed. May, 2002, Fantagraphics Books. p. 16</ref> Lee, while claiming credit for the initial idea, has acknowledged Ditko's role, stating, "If Steve wants to be called co-creator, I think he deserves [it]".<ref>Ross, Jonathon. ''In Search of Steve Ditko'', BBC 4, September 16, 2007.</ref> Writer Al Nickerson believes "that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created the Spider-Man that we are familiar with today [but that] ultimately, Spider-Man came into existence, and prospered, through the efforts of not just one or two, but many, comic book creators".<ref>Nickerson, Al. "[http://alnickerson.blogspot.com/2009/02/who-really-created-spider-man.html Who Really Created Spider-Man?]" ''P.I.C. News'', 5 February 2009. Accessed 2009-02-17. [http://www.webcitation.org/5eea8wTXN Archived] 2009-02-17.</ref> |

|||

===1970s=== |

|||

In 1969, when the [[Iranian New Wave]] began with [[Dariush Mehrjui]]'s film ''[[The Cow (film)|Gāv]]'', Kiarostami helped set up a filmmaking department at the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanun) in Tehran. Its debut production and Kiarostami's first film was the twelve-minute ''[[The Bread and Alley]]'' (1970), a [[Neorealism (art)|neo-realistic]] short film about an unfortunate schoolboy's confrontation with an aggressive dog. ''[[Breaktime]]'' followed in 1972. The department went on to become one of Iran’s most famous film studios, producing not only Kiarostami's films, but acclaimed Persian films such as ''[[The Runner (Davandeh)|The Runner]]'' and ''[[Bashu, the Little Stranger]]''.<ref name="AKzeitgeit"/> |

|||

[[Image:BreadAlley2.jpg|thumb|left|170px|A close-up of the boy in Kiarostami's first film ''[[The Bread and Alley]]'' (1970)]] |

|||

In 2008, an anonymous donor bequeathed the [[Library of Congress]] the original 24 pages of Ditko art of ''Amazing Fantasy'' #15, including Spider-Man's debut and the stories "The Bell-Ringer", "Man in the Mummy Case", and "There Are Martians Among Us".<ref>[http://www.loc.gov/today/pr/2008/08-089.html "Library of Congress Receives Original Drawings for the First Spider-Man Story, 'Amazing Fantasy' #15"], [[Library of Congress]] [[press release]], April 30, 2008. [http://www.webcitation.org/5q8m1QvXp WebCitation archive]. Additionally: Raymond, Matt. [http://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2008/04/library-of-congress-acquires-spider-mans-birth-certificate "Library of Congress Acquires Spider-Man's 'Birth Certificate'"], Library of Congress Blog, April 30, 2008.<!--not a personal blog; government/institutional and allowable per "professionals in the field on which they write" at [[WP:IRS]]--> [http://www.webcitation.org/5q8mun5gG WebCitation archive].</ref> |

|||

In the 1970s, as part of the Iranian cinematic renaissance, Kiarostami pursued an [[individualism|individualistic]] style of film making.<ref name="AKStrictFS">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.filmref.com/journal2002.html |

|||

| title = Notes on Close Up – Iranian Cinema: Past, Present and Future |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2002 |

|||

| author = Hamid Dabashi |

|||

| publisher = Strictly Film School |

|||

}}</ref> When discussing his first film, he stated: |

|||

<blockquote>"''Bread and Alley'' was my first experience in cinema and I must say a very difficult one. I had to work with a very young child, a dog, and an unprofessional crew except for the cinematographer, who was nagging and complaining all the time. Well, the cinematographer, in a sense, was right because I did not follow the conventions of film making that he had become accustomed to."<ref name = "AKSynoptique"/> |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

===Commercial success=== |

|||

Following ''[[The Experience (film)|The Experience]]'' (1973), Kiarostami released ''[[The Traveller (film)|The Traveler]]'' (''Mossafer'') in 1974. ''The Traveller'' tells the story of Hassan Darabi, a troublesome, amoral ten-year-old boy in a small Iranian town. He wishes to see the [[Iran national football team]] play an important match in Tehran. In order to achieve that, he scams his friends and neighbors. After a number of adventures, he finally reaches Tehran stadium in time for the match. The film addresses the boy's determination in his goal, and his indifference to the effects of his actions on other people, particularly those closest to him. The film is an examination of human behavior and the balance of right and wrong. The film furthered Kiarostami's reputation of [[Realism (dramatic arts)|realism]], [[Diegesis|diegetic]] simplicity, and stylistic complexity, as well as showing a fascination with physical and spiritual journeys.<ref name="BBCAKseason">{{Cite web |

|||

[[File:Amazing Fantasy 15.jpg|thumb|''Amazing Fantasy'' #15 (Aug. 1962). The issue that first introduced the fictional character. It was a gateway to the commercial success to the superhero and inspired the launch of ''[[The Amazing Spider-Man]]'' comics. Cover art by [[Jack Kirby]] (penciller) & [[Steve Ditko]] (inker).<ref name="Daniels"/> ]] |

|||

| url = http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/festivals/abbas_kiarostami_2005.shtml |

|||

A few months after Spider-Man's introduction in ''Amazing Fantasy'' #15 (Aug. 1962), publisher Martin Goodman reviewed the sales figures for that issue and was shocked to find it to have been one of the nascent Marvel's highest-selling comics.<ref name="Daniels" />{{rp|97}} A solo [[ongoing series]] followed, beginning with ''[[The Amazing Spider-Man]]'' #1 (March 1963). The title eventually became Marvel's top-selling series<ref name="Wright"/>{{rp|211}} with the character swiftly becoming a cultural icon; a 1965 ''[[Esquire (magazine)|Esquire]]'' poll of college campuses found that college students ranked Spider-Man and fellow Marvel hero the [[Hulk (comics)|Hulk]] alongside [[Bob Dylan]] and [[Che Guevara]] as their favorite revolutionary icons. One interviewee selected Spider-Man because he was "beset by woes, money problems, and the question of existence. In short, he is one of us."<ref name="Wright" />{{rp|223}} Following Ditko's departure after issue #38 (July 1966), [[John Romita, Sr.]] replaced him as [[penciler]] and would draw the series for the next several years. In 1968, Romita would also draw the character's extra-length stories in the comics magazine ''[[The Spectacular Spider-Man#Magazine|The Spectacular Spider-Man]]'', a proto-[[graphic novel]] designed to appeal to older readers but which lasted only two issues.<ref>Saffel, Steve. ''Spider-Man the Icon: The Life and Times of a Pop Culture Phenomenon'' ([[Titan Books]], 2007) ISBN 978-1-84576-324-4, "A Not-So-Spectacular Experiment", p. 31</ref> Nonetheless, it represented the first Spider-Man spin-off publication, aside from the original series' [[annual publication|summer annuals]] that began in 1964. |

|||

| title = Abbas Kiarostami Season |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| author = David Parkinson |

|||

| publisher = BBC |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

An early 1970s Spider-Man story led to the revision of the [[Comics Code Authority|Comics Code]]. Previously, the Code forbade the depiction of the use of [[illegal drugs]], even negatively. However, in 1970, the [[Richard Nixon|Nixon]] administration's [[Department of Health, Education, and Welfare]] asked Stan Lee to publish an anti-drug message in one of Marvel's top-selling titles.<ref name="Wright" />{{rp|239}} Lee chose the top-selling [[Green Goblin Reborn!|''The Amazing Spider-Man;'' issues #96–98]] (May–July 1971) feature a [[story arc]] depicting the negative effects of drug use. In the story, Peter Parker's friend [[Harry Osborn]] becomes addicted to pills. When Spider-Man fights the [[Green Goblin]] (Norman Osborn, Harry's father), Spider-Man defeats the Green Goblin, by revealing Harry's drug addiction. While the story had a clear anti-drug message, the Comics Code Authority refused to issue its seal of approval. Marvel nevertheless published the three issues without the Comics Code Authority's approval or seal. The issues sold so well that the industry's self-censorship was undercut and the Code was subsequently revised.<ref name="Wright" />{{rp|239}} |

|||

In 1975, Kiarostami directed two short films ''[[So Can I]]'' and ''[[Two Solutions for One Problem]]''. In early 1976, he released ''[[Rang-ha (film)|Colors]]'', followed by the fifty-four minute film ''[[A Wedding Suit]]'', a story about three teenagers coming into conflict over a suit for a wedding.<ref name="C4AK">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.channel4.com/film/reviews/feature.jsp?id=145506&page=1 |

|||

| title = Abbas Kiarostami Masterclass |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Chris Payne |

|||

| publisher = Channel4 |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="StanfordAK">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.stanford.edu/group/psa/events/1999-00/kiarostami/filmography.utf8.html |

|||

| title = Films by Abbas Kiarostami |

|||

| year = 1999 |

|||

| author = |

|||

| publisher = Stanford University |

|||

}}</ref> Kiarostami's first [[feature film]] was the 112-minute ''[[The Report|Report]]'' (1977). It revolved around the life of a [[tax collector]] accused of accepting bribes; [[suicide]] was among its themes. In 1979, he produced and directed ''[[First Case, Second Case]]''. |

|||

In 1972, a second monthly [[ongoing series]] starring Spider-Man began: ''[[Marvel Team-Up]],'' in which Spider-Man was paired with other superheroes and villains. In 1976, his second solo series, ''[[Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man|The Spectacular Spider-Man]]'' began running parallel to the main series. A third series featuring Spider-Man, ''[[Web of Spider-Man]],'' launched in 1985, replacing ''[[Marvel Team-Up]]''. The launch of a fourth monthly title in 1990, the "adjectiveless" ''[[Peter Parker: Spider-Man|Spider-Man]]'' (with the storyline "[[Torment (comics)|Torment]]"), written and drawn by popular artist [[Todd McFarlane]], debuted with several different covers, all with the same interior content. The various versions combined sold over 3 million copies, an industry record at the time. There have generally been at least two ongoing Spider-Man series at any time. Several [[limited series]], [[One-shot (comics)|one-shots]], and loosely related comics have also been published, and Spider-Man makes frequent cameos and guest appearances in other comic series.<ref name="Wright" />{{rp|279}} |

|||

===1980s=== |

|||

In the early 1980s, Kiarostami directed several [[short film]]s including ''[[Dental Hygiene]]'' (1980), ''[[Orderly or Disorderly]]'' (1981), and ''[[The Chorus (Kiarostami film)|The Chorus]]'' (1982). In 1983, he directed ''[[Fellow Citizen]]'', but it was not until 1987 that Abbas began to gain recognition outside of Iran with the release of ''[[Where Is the Friend's Home?]]''. |

|||

The original ''Amazing Spider-Man'' ran through issue #441 (Nov. 1998). Writer-artist [[John Byrne (comics)|John Byrne]] then revamped the origin of Spider-Man in the 13-issue limited series ''[[Spider-Man: Chapter One]]'' (Dec. 1998 - Oct. 1999, with an issue #0 midway through and some months containing two issues), similar to Byrne's adding details and some revisions to Superman's origin in [[DC Comics]]' ''[[The Man of Steel (comics)|The Man of Steel]]''.<ref name="Byrne">{{cite web | url=http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=151=article | title=John Byrne: The Hidden Story | publisher=Comic book resources | accessdate=May 27, 2011 | author=Michael Thomas}}</ref> Running concurrently, ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' was restarted with vol. 2, #1 (Jan. 1999). With what would have been vol. 2, #59, Marvel reintroduced the original numbering, starting with #500 (Dec. 2003). |

|||

''Where Is the Friend's Home?'' tells a deceptively simple account of a conscientious eight-year-old schoolboy's quest to return his friend's notebook in a neighboring village lest his friend be expelled from school. The traditional beliefs of Iranian rural people were depicted throughout the movie. The film has been noted for its poetic use of the Iranian [[rural]] landscape and its earnest realism, both important elements of Kiarostami's work. Kiarostami also made the film from a child's point of view, without the condescending tone common to many films about children.<ref name="AKWorldRecord">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.eworldrecords.com/wherisfrienh.html |

|||

| title = Where Is the friend's home? |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-27 |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Rebecca Flint |

|||

| publisher = World records |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="AKzeitWFH">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/films/whereisthefriendshome/presskit.pdf |

|||

|format=PDF | title = Where Is the Friend's Home? |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-27 |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Chris Darke |

|||

| publisher = Zeitgeistfilms |

|||

| archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070127080038/http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/films/whereisthefriendshome/presskit.pdf | archivedate = January 27, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

By the end of 2007, Spider-Man regularly appeared in ''The Amazing Spider-Man,'' ''[[The New Avengers (comics)|New Avengers]]'', ''[[Spider-Man Family]]'', and various limited series in mainstream Marvel Comics continuity, as well as in the [[Parallel universe (fiction)|alternate-universe]] series ''[[Spider-Girl|The Amazing Spider-Girl]],'' the [[Ultimate Marvel|Ultimate Universe]] title ''[[Ultimate Spider-Man]],'' the alternate-universe [[Preadolescence|tween]] series ''[[Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane]],'' the alternate-universe children's series ''[[Marvel Adventures Spider-Man]]'', and ''[[Marvel Adventures: The Avengers]].'' |

|||

''Where Is the Friend's Home?'', ''[[And Life Goes On]]'' (1992) (also known as ''Life and Nothing More''), and ''[[Through the Olive Trees]]'' (1994) are described by critics as the ''[[Koker trilogy]]'', because all three films feature the village of [[Koker]] in northern Iran. The films are based around the [[1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake]] in which 40,000 people lost their lives; Kiarostami uses the themes of life, death, change, and continuity to connect the films. The trilogy went on to become successful in France in the 1990s and other countries such as the [[Netherlands]], [[Sweden]], Germany and [[Finland]].<ref name="AKBBC2005">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/festivals/abbas_kiarostami_2005.shtml |

|||

| title = Abbas Kiarostami Season: National Film Theatre, 1st-31 May 2005 |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| author = David Parkinson |

|||

| publisher = BBC |

|||

}}</ref> However, Kiarostami does not consider the 3 films as part of a trilogy, suggesting instead that the last two titles plus ''Taste of Cherry'' (1997) comprise a trilogy, given their common theme – the preciousness of life.<ref name="CriterionAK">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.criterion.com/asp/release.asp?id=45&eid=63§ion=essay |

|||

| title = Taste of Cherry |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Godfrey Cheshire |

|||

| publisher = The Criterion Collection |

|||

}}</ref> In 1987, Kiarostami was involved in the screenwriting of ''[[Kelid|The Key]]'', which he edited but did not direct. In 1989, he released ''[[Homework (1989 film)|Homework]]''. |

|||

When primary series ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' reached issue #545 (Dec. 2007), Marvel dropped its spin-off ongoing series and instead began publishing ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' three times monthly, beginning with #546-549 (each Jan. 2008). The three times monthly scheduling of ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' lasted until November 2010 when the comic book was increased from 22 pages to 30 pages each issue and published only twice a month, beginning with #648-649 (each Nov. 2010). The following year (Nov. 2011) Marvel started publishing ''[[Avenging Spider-Man]]'' as the first spin-off ongoing series in addition to the still twice monthly ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' since the previous ones were cancelled at the end of 2007. |

|||

===1990s=== |

|||

Kiarostami first film of the decade was ''[[Close-Up (film)|Close-Up]]'' (1990), which narrates the story of the real-life trial of a man who impersonated film-maker [[Mohsen Makhmalbaf]], conning a family into believing they would star in his new film. The family suspects theft as the motive for this charade, but the impersonator, Hossein Sabzian, argues that his motives were more complex. The part documentary, part staged film examines Sabzian's moral justification for usurping Makhmalbaf's identity, questioning his ability to sense his cultural and artistic flair.<ref name="AKslant">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/film_review.asp?ID=101 |

|||

| title = Close Up |

|||

| year = 2002 |

|||

| author = Ed Gonzalez |

|||

| publisher = Slant Magazine |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="AKCombustibleCelluloid">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.combustiblecelluloid.com/closeup.shtml |

|||

| title = Close-Up: Holding a Mirror up to the Movies |

|||

| year = 2000 |

|||

| author = Jeffrey M. Anderson |

|||

| publisher = Combustible Celluloid |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-02-22 |

|||

}}</ref> ''Close-Up'' received praise from directors such as [[Quentin Tarantino]], [[Martin Scorsese]], [[Werner Herzog]], [[Jean-Luc Godard]], and [[Nanni Moretti]]<ref name="AKBfiVideoPublishing">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.amazon.co.uk/Close-Up-Hossain-Sabzian/dp/B00004CWIZ |

|||

| title = Close-Up |

|||

| year = 1998 |

|||

| publisher = Bfi Video Publishing |

|||

}}</ref> and was released across Europe.<ref name="AKTheHindu">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/fr/2005/05/13/stories/2005051303400400.htm |

|||

| title = Celebrating film-making |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| author = Hemangini Gupta |

|||

| publisher = The Hindu |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

==Comic book character== |

|||

In 1992, Kiarostami directed ''[[Life, and Nothing More...]]'', regarded by critics as the second film of the Koker trilogy. The film follows a father and his young son as they drive from Tehran to Koker in search of two young boys who they fear might have perished in the 1990 earthquake. As they travel through the devastated landscape, they meet earthquake survivors forced to carry on with their lives amid tragedy.<ref name="MMartyrAK">{{Cite web |

|||

[[Image:Spider-Man spider-bite.jpg|200px|thumb|left|The spider bite that gave Peter Parker his powers. ''[[Amazing Fantasy]]'' #15, art by [[Steve Ditko]].]] |

|||

| url = http://www.moviemartyr.com/1991/lifeandnothingmore.htm |

|||

In [[Forest Hills, Queens]], [[New York City]],<ref name=kempton /> [[high school]] student Peter Parker is a science- whiz orphan living with his [[Uncle Ben]] and [[Aunt May]]. As depicted in ''[[Amazing Fantasy]]'' #15 (Aug. 1962), he is bitten by a [[radioactive]] [[spider]] (erroneously classified as an [[insect]] in the panel) at a science exhibit and "acquires the agility and proportionate strength of an [[arachnid]]."<ref name="Debut">{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]] | artist=[[Steve Ditko|Ditko, Steve]] | story= | title=[[Amazing Fantasy]] | issue=15 |date = August 1962| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> Along with super strength, he gains the ability to adhere to walls and ceilings. Through his native knack for science, he develops a gadget that lets him fire adhesive webbing of his own design through small, wrist-mounted barrels. Initially seeking to capitalize on his new abilities, he dons a costume and, as "Spider-Man", becomes a novelty television star. However, "He blithely ignores the chance to stop a fleeing thief, [and] his indifference ironically catches up with him when the same criminal later robs and kills his Uncle Ben."<ref name=daniels95 /> Spider-Man tracks and subdues the killer and learns, in the story's next-to-last caption, "With great power there must also come—great responsibility!"<ref name=daniels95> |

|||

| title = Life and Nothing More… (Abbas Kiarostami) 1991 |

|||

[[Les Daniels|Daniels, Les]]. ''Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics'' (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1991) ISBN 0-8109-3821-9, p. 95</ref> |

|||

| year = 2002 |

|||

| author = Jeremy Heilman |

|||

| publisher = MovieMartyr |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="ChicagoReaderAK">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.chicagoreader.com/movies/archives/1998/0598/05298.html |

|||

| title = Fill In The Blanks |

|||

| year = 1997 |

|||

| author = Jonathan Rosenbaum |

|||

| publisher = Chicago Reader |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="ZeitinfoAK">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/film.php?directoryname=andlifegoeson |

|||

| title = And Life Goes On (synopsis) |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Film Info |

|||

| publisher = Zeitgeistfilms |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

That year Kiarostami won a [[Roberto Rossellini|Prix Roberto Rossellini]], the first professional film award of his career, for his direction of the film. The last film of the so-called ''Koker trilogy'' was ''Through the Olive Trees'' (1994), which turns a peripheral scene from ''Life and Nothing More'' into the central drama.<ref name="SenseCinemaAK1">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2003/29/kiarostami_rural_space_and_place/ |

|||

| title = Days in the Country: Representations of Rural Space ... |

|||

| year = 2003 |

|||

| author = Stephen Bransford |

|||

| publisher = Sense of Cinema |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Critics such as [[Adrian Martin]] have called the style of filmmaking in the ''Koker trilogy'' as "diagrammatical", linking the zig-zagging patterns in the landscape and the geometry of forces of life and the world.<ref name="FilmIrelandAK1">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.filmireland.net/reviews/kiarostami.htm |

|||

| title = Kiarostami: The Art of Living |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Maximilian Le Cain |

|||

| publisher = Film Ireland |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="BFIAKWID">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/issue/200505 |

|||

| title = Where is the director? |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| author = |

|||

| publisher = British Film Institute |

|||

}}</ref> A flashback of the zigzag path in ''Life and Nothing More...'' (1992) in turn triggers the spectator’s memory of the previous film, ''Where Is the Friend’s Home?'' back in 1987, shot before the earthquake. This in turn symbolically links to post-earthquake reconstruction in ''Through the Olive Trees'' in 1994. |

|||

Despite his superpowers, Parker struggles to help his widowed aunt pay rent, is taunted by his peers—particularly football star [[Flash Thompson]]—and, as Spider-Man, engenders the editorial wrath of [[newspaper]] publisher [[J. Jonah Jameson]].<ref name=saffel21>Saffel, Steve. ''Spider-Man the Icon: The Life and Times of a Pop Culture Phenomenon'' ([[Titan Books]], 2007) ISBN 978-1-84576-324-4, p. 21</ref><ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]] | artist=[[Steve Ditko|Ditko, Steve]] | story= Spider-Man"; "Spider-Man vs. The Chameleon"; "Duel to the Death with the Vulture; "The Uncanny Threat of the Terrible Tinkerer! | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man]] | volume=1 | issue=1-2 | date= March, May 1963 | publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> As he battles his enemies for the first time,<ref name=gcd>[http://www.comics.org/series/1570/ ''Amazing Spider-Man, The'' (Marvel, 1963 Series)] at the [[Grand Comics Database]]</ref> Parker finds juggling his personal life and costumed adventures difficult. In time, Peter graduates from high school,<ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]] | artist=[[Steve Ditko|Ditko, Steve]] | story= The Menace of the Molten Man! | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man]] | volume=1 | issue=28 | date= September 1965 | publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> and enrolls at [[Empire State University]] (a fictional institution evoking the real-life [[Columbia University]] and [[New York University]]).,<ref name=saffel51>Saffel, p. 51</ref> where he meets roommate and best friend [[Harry Osborn]] and first girlfriend [[Gwen Stacy]],<ref name="mnyc">{{cite book | last = Sanderson | first = Peter | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = The Marvel Comics Guide to New York City | publisher = [[Pocket Books]] | year = 2007 | location = New York City | pages = 30–33 | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 1-14653-141-6}}</ref> and Aunt May introduces him to [[Mary Jane Watson]].<ref name=gcd /><ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]] | artist=[[John Romita, Sr.|Romita, John]] | story= The Birth of a Super-Hero! | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man]] | volume=1 | issue=42 | date= November 1966| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref><ref name=saffel27>Saffel, p. 27</ref> As Peter deals with Harry's drug problems, and Harry's father is revealed to be Spider-Man's nemesis the [[Green Goblin]], Peter even attempts to give up his costumed identity for a while.<ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]] | penciller=[[John Romita, Sr.|Romita, John]] | inker=[[Mike Esposito (comics)|Mickey Demeo]] | story= Spider-Man No More! | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man]] | volume=1 | issue=50 | date= July 1967 | publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref><ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Stan Lee|Lee, Stan]] | penciller=[[Gil Kane|Kane, Gil]] | inker=[[Frank Giacoia|Giacoia, Frank]] | story= The Spider or the Man? | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man]] | volume=1 | issue=100 | date= September 1971| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> Gwen's Stacy's father, [[New York City Police]] detective captain [[George Stacy]] is accidentally killed during a battle between Spider-Man and [[Doctor Octopus]] (#90, Nov. 1970).<ref name=saffel60>Saffel, p. 60</ref> In the course of his adventures Spider-Man has made a wide variety of friends and contacts within the superhero community, who often come to his aid when he faces problems that he cannot solve on his own. |

|||

In 1995, [[Miramax Films]] released ''Through the Olive Trees'' in the US theatrically. Kiarostami next wrote the screenplays for [[The Journey (1995 film)|''The Journey'']] and ''[[The White Balloon]]'' (1995), for his former assistant [[Jafar Panahi]].<ref name="AKzeitgeit"/> Between 1995 and 1996, he was involved in the production of ''[[Lumière and Company]]'', a collaboration with 40 other film directors. Kiarostami won the ''[[Palme d'Or]]'' (Golden Palm) award at the [[1997 Cannes Film Festival|Cannes Film Festival]] for ''[[Taste of Cherry]]'',<ref name="festival-cannes.com">{{Cite web |url=http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/4835/year/1997.html |title=Festival de Cannes: Taste of Cherry |accessdate=2009-09-23 |work=festival-cannes.com}}</ref> the tale of a man, Mr. Badii, determined to commit suicide. The film involved themes such as morality, the legitimacy of the act of suicide, and the meaning of compassion.<ref name="SenseCinemaSuicide">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/9/taste.html |

|||

| title = Concepts of Suicide in Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry |

|||

| year = 2000 |

|||

| author = Constantine Santas |

|||

| publisher = Sense of Cinema |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

In [[The Night Gwen Stacy Died|issue #121]] (June 1973),<ref name = gcd /> the Green Goblin throws [[Gwen Stacy]] from a tower of either the [[Brooklyn Bridge]] (as depicted in the art) or the [[George Washington Bridge]] (as given in the text).<ref>Saffel, p. 65, states, "In the battle that followed atop the Brooklyn Bridge (or was it the George Washington Bridge?)...." On page 66, Saffel reprints the panel of ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' #121, page 18, in which Spider-Man exclaims, "The George Washington Bridge! It figures Osborn would pick something named after his favorite president. He's got the same sort of hangup for dollar bills!" Saffel states, "The span portrayed...is the GW's more famous cousin, the Brooklyn Bridge. ... To address the contradiction in future reprints of the tale, though, Spider-Man's dialogue was altered so that he's referring to the Brooklyn Bridge. But the original snafu remains as one of the more visible errors in the history of comics."</ref><ref>Sanderson, ''Marvel Universe'', p. 84, notes, "[W]hile the script described the site of Gwen's demise as the George Washington Bridge, the art depicted the Brooklyn Bridge, and there is still no agreement as to where it actually took place."</ref> She dies during Spider-Man's rescue attempt; a note on the letters page of issue #125 states: "It saddens us to say that the [[Whiplash (medicine)|whiplash effect]] she underwent when Spidey's webbing stopped her so suddenly was, in fact, what killed her."<ref name=saffel65>Saffel, p. 65</ref> The following issue, the Goblin appears to accidentally kill himself in the ensuing battle with Spider-Man.<ref name="GwenDeath">{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Gerry Conway|Conway, Gerry]] | penciller=[[Gil Kane|Kane, Gil]] | inker=[[John Romita Sr.|Romita, John]] | story=The Night Gwen Stacy Died | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man]] | volume=1 | issue=121 | date=June 1973 | publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> |

|||

Kiarostami directed ''[[The Wind Will Carry Us]]'' in 1999, which won the Grand Jury Prize (Silver Lion) at the [[Venice Film Festival|Venice International Film Festival]]. The film contrasted rural and urban views on the dignity of labor, addressing themes of gender equality and the benefits of progress, by means of a stranger's sojourn in a remote [[Kurdistan|Kurdish]] village.<ref name="AKBBC2005"/> An interesting feature of the movie is that many of the characters are heard but not seen, and there are at least thirteen to fourteen characters in the film who remain invisible throughout.<ref name="GuardianUnlimitedinterview">{{Cite news |

|||

| url = http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2005/apr/28/hayfilmfestival2005.guardianhayfestival |

|||

| title = Abbas Kiarostami, interview |

|||

| author =Geoff Andrew |

|||

| publisher = Guardian Unlimited |

|||

| location=London |

|||

| date=2005-05-25 |

|||

| accessdate=2010-04-12}}</ref> |

|||

Working through his grief, Parker eventually develops tentative feelings toward Watson, and the two "become confidants rather than lovers."<ref name = Sanderson85>Sanderson, ''Marvel Universe'', p. 85</ref> Parker graduates from college in issue #185,<ref name=gcd /> and becomes involved with the shy Debra Whitman and the extroverted, flirtatious costumed thief Felicia Hardy, the [[Black Cat (comics)|Black Cat]],<ref name=sanderson83>Sanderson, ''Marvel Universe'', p. 83</ref> whom he meets in issue #194 (July 1979).<ref name=gcd /> |

|||

===2000s=== |

|||

From 1984 to 1988, Spider-Man wore a different costume than his original. Black with a white spider design, this new costume originated in the ''[[Secret Wars]]'' [[limited series]], on an alien planet where Spider-Man participates in a battle between Earth's major superheroes and villains.<ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Jim Shooter|Shooter, Jim]] | penciller=[[Mike Zeck|Zeck, Michael]] | inker=[[John Beatty (illustrator)|Beatty, John]], [[Jack Abel|Abel, Jack]], and [[Mike Esposito (comics)|Esposito, Mike]] | story= Invasion | title=[[Secret Wars|Marvel Super-Heroes Secret Wars]] | volume=1 | issue=8 | date= December 1984| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> Not unexpectedly, the change to a longstanding character's iconic design met with controversy, "with many hardcore comics fans decrying it as tantamount to sacrilege. Spider-Man's traditional red and blue costume was iconic, they argued, on par with those of his D.C. rivals Superman and Batman."<ref name=cc>Leupp, Thomas. [http://www.reelzchannel.com/article.aspx?articleId=292 "Behind the Mask: The Story of Spider-Man's Black Costume"], ReelzChannel.com, 2007, n.d. [http://www.webcitation.org/5qn5Uiwyw WebCitation archive].</ref> The creators then revealed the costume was an alien [[Symbiote (comics)|symbiote]] which Spider-Man is able to reject after a difficult struggle,<ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Louise Simonson|Simonson, Louise]] | penciller=[[Greg LaRocque|LaRocque, Greg]] | inker=[[Jim Mooney|Mooney, Jim]] and [[Vince Colletta|Colletta, Vince]] | story= 'Til Death Do Us Part! | title=[[Web of Spider-Man]] | volume=1 | issue=1 | date= April 1985| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> though the symbiote returns several times as [[Venom (comics)|Venom]] for revenge.<ref name=gcd /> |

|||

In 2001, Kiarostami and his assistant, Seifollah Samadian, traveled to [[Kampala]], [[Uganda]] at the request of the [[United Nations]] [[International Fund for Agricultural Development]], to film a documentary about programs assisting Ugandan orphans. He stayed for ten days and made ''[[ABC Africa]]''. The trip was originally intended as a research in preparation for the actual filming, but Kiarostami ended up editing the entire film from the video footage obtained.<ref>Geoff Andrew, ''Ten'' (London: BFI Publishing, 2005), p. 35.</ref> Although Uganda's orphans are overwhelmingly the result of the [[HIV/AIDS in Africa|AIDS epidemic]], ''[[Time Out (company)|Time Out]]'' editor and [[BFI Southbank|National Film Theatre]] chief programmer Geoff Andrew stated about Kiarostami's film: "Like his previous four features, this film is not about death but life-and-death: how they're linked, and what attitude we might adopt with regard to their symbiotic inevitability."<ref>Geoff Andrew, ''Ten'', (London: BFI Publishing, 2005) p. 32.</ref> |

|||

Parker proposes to Watson in ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' #290 (July 1987), and she accepts two issues later, with [[The Wedding! (comics)|the wedding]] taking place in ''The Amazing Spider-Man Annual'' #21 (1987)—promoted with a real-life mock wedding using actors at [[Shea Stadium]], with Stan Lee officiating, on June 5, 1987.<ref name=saffel124>Saffel, p. 124</ref><ref name="Wedding">{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Jim Shooter|Shooter, Jim]] and [[David Michelinie|Michelinie, David]]| penciller=[[Paul Ryan (comics)|Ryan, Paul]] | inker=[[Vince Colletta|Colletta, Vince]] | story= The Wedding | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man Annual]] | volume=1 | issue=21 | date= 1987| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> However, [[David Michelinie]], who scripted based on a plot by editor-in-chief [[Jim Shooter]], said in 2007, "I didn't think they actually should [have gotten] married. ... I had actually planned another version, one that wasn't used."<ref name=saffel124 /> In a controversial storyline, Peter becomes convinced that [[Ben Reilly]], the [[Scarlet Spider]] (a clone of Peter created by his college professor [[Jackal (Marvel Comics)|Miles Warren]]) is the real Peter Parker, and that he, Peter, is the clone. Peter gives up the Spider-Man identity to Reilly for a time, until Reilly is killed by the returning Green Goblin and revealed to be the clone after all.<ref name="Life of Reilly">{{cite web|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/19960101-re_/http://www.newcomicreviews.com/GHM/specials/LifeOfReilly/|archivedate=1996-01-01|url=http://www.newcomicreviews.com/GHM/specials/LifeOfReilly/|publisher= NewComicsReviews.com|title= "Life of Reilly", 35-part series, ''GreyHaven Magazine'', 2003, n.d.}}</ref> In stories published in 2005 and 2006 (such as "[[Spider-Man: The Other|The Other]]"), he develops additional spider-like abilities including biological web-shooters, toxic stingers that extend from his forearms, the ability to stick individuals to his back, enhanced Spider-sense and night vision, and increased strength and speed. Peter later becomes a member of the [[New Avengers]], and reveals his civilian identity to the world,<ref>{{ Cite comic | writer=[[Mark Millar|Millar, Mark]]| penciller=[[Steve McNiven|McNiven, Steve]] | inker=[[Dexter Vines|Vines, Dexter]] | story= Civil War| title=[[Civil War (comics)|Civil War]] | volume=1 | issue=2 | date= August 2006| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] | location=[[New York, NY]] }}</ref> furthering his already numerous problems. His marriage to Mary Jane and public unmasking are later erased in the controversial<ref name=OMDPart1p1>Weiland, Jonah. [http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=12230 "The 'One More Day' Interviews with Joe Quesada, Pt. 1 of 5"], ''[[Newsarama]]'', December 28, 2007. [http://www.webcitation.org/5qkzIuMKI WebCitation archive].</ref> storyline "[[Spider-Man: One More Day|One More Day]]", in a [[Faustian bargain]] with the demon [[Mephisto (comics)|Mephisto]], resulting in several adjustments to the timeline, such as the resurrection of Harry Osborn, the erasure of Parker's marriage, and the return of his traditional tools and powers.<ref name="OneMoreDay">{{ Cite comic | writer=[[J. Michael Straczynski|Straczynski, J. Michael]] | penciller=[[Joe Quesada|Quesada, Joe]] | inker=Miki, Danny | story= One More Day Part 4 | title=[[The Amazing Spider-Man]] | volume= | issue=545 | date= Dec. 2007| publisher=[[Marvel Comics]] }}</ref> |

|||

The following year, Kiarostami directed ''[[Ten (film)|Ten]]'', revealing an unusual method of filmmaking and abandoning many scriptwriting conventions.<ref name="GuardianUnlimitedinterview"/> Kiarostami focused on the socio-political landscape of Iran, and the images are seen through the eyes of one woman as she drives through the streets of Tehran over a period of several days. Her journey is composed of ten conversations with various passengers, which include her sister, a hitchhiking prostitute and a jilted bride and her demanding young son. This style of filmmaking was praised by a number of professional film critics such as [[A. O. Scott]] in ''[[The New York Times]]'', who wrote that Kiarostami, "in addition to being perhaps the most internationally admired Iranian filmmaker of the past decade, is also among the world masters of automotive cinema...He understands the automobile as a place of reflection, observation and, above all, talk."<ref name="ZeitGeistTen">{{Cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.zeitgeistfilms.com/film.php?directoryname=ten |

|||

| title = Ten (film) synopsis |

|||

| accessdate=2007-02-23 |

|||

| date = |

|||

| author = Ten info |

|||

| publisher = Zeitgeistfilms |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

That storyline came at the behest of editor-in-chief [[Joe Quesada]], who said, "Peter being single is an intrinsic part of the very foundation of the world of Spider-Man".<ref name=OMDPart1p1/> It caused unusual public friction between Quesada and writer [[J. Michael Straczynski]], who "told Joe that I was going to take my name off the last two issues of the [story] arc" but was talked out of doing so.<ref name=OMDPart2p1>Weiland, Jonah. [http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=12238 "The 'One More Day' Interviews with Joe Quesada, Pt. 2 of 5"], ''[[Newsarama]]'', December 31, 2007. [http://www.webcitation.org/5qkz3fKei WebCitation archive].</ref> At issue with Straczynski's climax to the arc, Quesada said, was |

|||

In 2003, Kiarostami directed ''[[Five (2003 film)|Five]]'', a poetic feature with no dialogue or characterization. It consists of five long shots of nature which are single-take sequences, shot with a hand-held [[DV]] camera, along the shores of the [[Caspian Sea]]. Although the film lacks a clear storyline, Geoff Andrew argues that the film is "more than just pretty pictures". He further adds, "Assembled in order, they comprise a kind of abstract or emotional narrative arc, which moves evocatively from separation and solitude to community, from motion to rest, near-silence to sound and song, light to darkness and back to light again, ending on a note of rebirth and regeneration."<ref>Geoff Andrew, ''Ten'', (London: BFI Publishing, 2005) pp 73–4.</ref> He further notes the degree of artifice concealed behind the apparent simplicity of the imagery. |

|||

{{bquote|...that we didn't receive the story and methodology to the resolution that we were all expecting. What made that very problematic is that we had four writers and artists well underway on [the sequel arc] "Brand New Day" that were expecting and needed "One More Day" to end in the way that we had all agreed it would. ... The fact that we had to ask for the story to move back to its original intent understandably made Joe upset and caused some major delays and page increases in the series. Also, the science that Joe was going to apply to the [[retcon]] of the marriage would have made over 30 years of Spider-Man books worthless, because they never would have had happened. ...[I]t would have reset way too many things outside of the Spider-Man titles. We just couldn't go there....<ref name=OMDPart2p1 />}} |

|||

Kiarostami produced ''[[10 on Ten]]'', a journal documentary that shares ten lessons on movie-making while driving through the locations of his past films, in 2004. The movie is shot on digital video with a stationary camera mounted inside the car, in a manner reminiscent of ''Taste of Cherry'' and ''Ten''. In 2005 and 2006, he directed ''[[The Roads of Kiarostami]]'', a 32-minute documentary that reflects on the power of landscape, combining austere black-and-white photographs with poetic observations, engaging music with political subject matter. Also in 2005, Kiarostami contributed the central section to ''[[Tickets (film)|Tickets]]'', a [[anthology film|portmanteau film]] set on a train traveling through Italy. The other segments were directed by [[Ken Loach]] and [[Ermanno Olmi]]. In 2008 he directed the feature ''[[Shirin (film)|Shirin]]''. |

|||

<!--Every current thing that goes on needs to be cited. If by an issue please use [[Template:Cite comics]] because citations are normally meant to be unbare. Sorry for the trouble but a certain editor is striving for this article to maybe be a Featured article in the future and everything needs to be reliable. Happy editing--> |

|||

=== |

===Personality=== |

||

{{quote box|width=33%|quote="People often say glibly that Marvel succeeded by blending super hero adventure stories with soap opera. What Lee and Ditko actually did in ''[[The Amazing Spider-Man]]'' was to make the series an ongoing novelistic chronicle of the lead character's life. Most super heroes had problems no more complex or relevant to their readers' lives than thwarting this month's bad guys.... Parker had far more serious concern in his life: coming to terms with the death of a loved one, falling in love for the first time, struggling to make a living, and undergoing crises of conscience."|source=Comics historian [[Peter Sanderson]]<ref>[[Peter Sanderson|Sanderson, Peter]]. ''Marvel Universe: The Complete Encyclopedia of Marvel's Greatest Characters'' (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1998) ISBN 0-8109-8171-8, p. 75</ref>}} |

|||

''[[Certified Copy (film)|Certified Copy]]'' (2010) was made in Tuscany, Kiarostami's first film to be shot and produced outside Iran. The story of an encounter between a British man and a French woman, it was entered in competition for the [[Palme d'Or]] in the [[2010 Cannes Film Festival]]. |

|||

As one contemporaneous journalist observed, "Spider-Man has a terrible identity problem, a marked [[inferiority complex]], and a fear of women. He is [[Antisocial personality disorder|anti-social]], [sic] [[castration]]-ridden, racked with [[Oedipus complex|Oedipal guilt]], and accident-prone ... [a] functioning [[neurotic]]".<ref name=kempton>Kempton, Sally, "Spiderman's [sic] Dilemma: Super-Anti-Hero in Forest Hills", ''[[The Village Voice]]'', April 1, 1965</ref> Agonizing over his choices, always attempting to do right, he is nonetheless viewed with suspicion by the authorities, who seem unsure as to whether he is a helpful vigilante or a clever criminal.<ref name=daniels96>Daniels, p. 96</ref> |

|||

Notes cultural historian Bradford W. Wright, |

|||

==Cinematic style== |

|||

{{blockquote|Spider-Man's plight was to be misunderstood and persecuted by the very public that he swore to protect. In the first issue of ''The Amazing Spider-Man'', J. Jonah Jameson, publisher of the ''[[Daily Bugle]]'', launches an editorial campaign against the "Spider-Man menace." The resulting negative publicity exacerbates popular suspicions about the mysterious Spider-Man and makes it impossible for him to earn any more money by performing. Eventually, the bad press leads the authorities to brand him an outlaw. Ironically, Peter finally lands a job as a photographer for Jameson's ''[[Daily Bugle]]''.<ref name="Wright"/>{{rp|212}}}} |

|||

{{Main|Cinematic style of Abbas Kiarostami}} |

|||

The mid-1960s stories reflected the political tensions of the time, as early 1960s Marvel stories had often dealt with the [[Cold War]] and [[Communism]].<ref name="Wright"/>{{rp|220-223}} As Wright observes, |

|||

===Individualism=== |

|||

{{blockquote|From his high-school beginnings to his entry into college life, Spider-Man remained the superhero most relevant to the world of young people. Fittingly, then, his comic book also contained some of the earliest references to the politics of young people. In 1968, in the wake of actual militant [[student demonstration]]s at Columbia University, Peter Parker finds himself in the midst of similar unrest at his Empire State University. ... Peter has to reconcile his natural sympathy for the students with his assumed obligation to combat lawlessness as Spider-Man. As a law-upholding liberal, he finds himself caught between militant leftism and angry conservatives.<ref name="Wright"/>{{rp|234-235}}}} |

|||

Though Kiarostami has been compared to [[Satyajit Ray]], [[Vittorio De Sica|Vittorio de Sica]], [[Éric Rohmer]], and [[Jacques Tati]], his films exhibit a singular style, often employing techniques of his own invention.<ref name="AKzeitgeit"/> |

|||

==Other versions== |

|||

During the filming of ''The Bread and Alley'' in 1970, Kiarostami had major differences with his experienced [[cinematographer]] about how to film the boy and the attacking dog. While the cinematographer wanted separate shots of the boy approaching, a close up of his hand as he enters the house and closes the door, followed by a shot of the dog, Kiarostami believed that if the three scenes could be captured as a whole it would have a more profound impact in creating tension over the situation. That one shot took around forty days to complete, until Kiarostami was fully content with the scene. Abbas later commented that the breaking of scenes would have disrupted the [[rhythm]] and content of the film's structure, preferring to let the scene flow as one.<ref name = "AKSynoptique"/> |

|||

{{Main|Alternative versions of Spider-Man}} |

|||

Due to Spider-Man's popularity in the mainstream [[Marvel Universe]], publishers have been able to introduce different variations of Spider-Man outside of mainstream comics as well as reimagined stories in many other [[Multiverse (Marvel Comics)|multiversed]] spinoffs such as ''[[Ultimate Spider-Man]]'', ''[[Spider-Man 2099]]'', and ''[[Spider-Man: India]]''. Marvel has also made its own parodies of Spider-Man in comics such as ''[[Not Brand Echh]]'', which was published in the late 1960s and featured such characters as Peter Pooper alias Spidey-Man,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dialbforblog.com/archives/180/ |title=examples of "Not Brand Echh" comics |publisher=Dialbforblog.com |date= |accessdate=2010-04-10}}</ref> and Peter Porker, the Spectacular [[Spider-Ham]], who appeared in the 1980s. The fictional character has also inspired a number of deratives such as a [[Spider-Man: The Manga|manga version of Spider-Man]] drawn by |

|||