Katakana: Difference between revisions

wording |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

{{Calligraphy}} |

{{Calligraphy}} |

||

{{stack end}} |

{{stack end}} |

||

{{nihongo|'''Katakana'''|[[wikt:片仮名|片仮名]], カタカナ {{lang|en|or}} かたかな|}} is a [[Japanese language|Japanese]] [[syllabary]], one component of the [[Japanese writing system]] along with [[hiragana]],<ref>Roy Andrew Miller, ''A Japanese Reader: Graded Lessons in the Modern Language'', Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Tokyo, Japan (1966), p. 28, Lesson 7 : Katakana : ''a—no''. "Side by side with hiragana, modern Japanese writing makes use of another complete set of similar symbols called the katakana."</ref> [[kanji]], and in some cases the [[Latin alphabet]]. The word ''katakana'' means "fragmentary |

{{nihongo|'''Katakana'''|[[wikt:片仮名|片仮名]], カタカナ {{lang|en|or}} かたかな|}} is a [[Japanese language|Japanese]] [[syllabary]], one component of the [[Japanese writing system]] along with [[hiragana]],<ref>Roy Andrew Miller, ''A Japanese Reader: Graded Lessons in the Modern Language'', Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Tokyo, Japan (1966), p. 28, Lesson 7 : Katakana : ''a—no''. "Side by side with hiragana, modern Japanese writing makes use of another complete set of similar symbols called the katakana."</ref> [[kanji]], and in some cases the [[Latin alphabet]]. Katakana and hiragana are both [[kana]] systems; they have corresponding character sets in which each character represents one [[mora (linguistics)|mora]] (one sound in the Japanese language). The word ''katakana'' means "fragmentary kana", as the katakana scripts are derived from components of more complex kanji. Each kana represents one [[mora (linguistics)|mora]]. Each kana is either a vowel such as ''"a"'' (katakana [[wikt:ア|ア]]); a consonant followed by a vowel such as ''"ka"'' (katakana [[wikt:カ|カ]]); or ''"n"'' (katakana [[wikt:ン|ン]]), a [[nasal stop|nasal]] [[sonorant]] which, depending on the context, sounds either like English ''m'', ''n'', or ''ng'' ({{IPAblink|ŋ}}), or like the [[nasal vowel]]s of [[French language|French]]. |

||

In contrast to the [[hiragana]] syllabary, which is used for those Japanese language words and grammatical inflections which [[kanji]] does not cover, the katakana syllabary is primarily used for [[Transcription (linguistics)|transcription]] of foreign language words [[transcription into Japanese|into Japanese]] and the writing of [[loan word]]s (collectively [[gairaigo]]). It is also used for emphasis, to represent [[onomatopoeia]], and to write certain Japanese language words, such as technical and scientific terms, and the names of plants, animals, and minerals. Names of Japanese companies are also often written in katakana rather than the other systems. |

In contrast to the [[hiragana]] syllabary, which is used for those Japanese language words and grammatical inflections which [[kanji]] does not cover, the katakana syllabary is primarily used for [[Transcription (linguistics)|transcription]] of foreign language words [[transcription into Japanese|into Japanese]] and the writing of [[loan word]]s (collectively [[gairaigo]]). It is also used for emphasis, to represent [[onomatopoeia]], and to write certain Japanese language words, such as technical and scientific terms, and the names of plants, animals, and minerals. Names of Japanese companies are also often written in katakana rather than the other systems. |

||

Revision as of 17:23, 21 May 2012

| Katakana カタカナ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | ~800 AD to the present |

| Direction | Vertical right-to-left, left-to-right |

| Languages | Japanese, Okinawan, Ainu, Palauan[1] |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Hiragana, Hentaigana |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Kana (411), Katakana |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Katakana |

| U+30A0–U+30FF, U+31F0–U+31FF, U+3200–U+32FF, U+FF00–U+FFEF, U+1B000–U+1B0FF | |

|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

Katakana (片仮名, カタカナ or かたかな) is a Japanese syllabary, one component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana,[2] kanji, and in some cases the Latin alphabet. Katakana and hiragana are both kana systems; they have corresponding character sets in which each character represents one mora (one sound in the Japanese language). The word katakana means "fragmentary kana", as the katakana scripts are derived from components of more complex kanji. Each kana represents one mora. Each kana is either a vowel such as "a" (katakana ア); a consonant followed by a vowel such as "ka" (katakana カ); or "n" (katakana ン), a nasal sonorant which, depending on the context, sounds either like English m, n, or ng ([ŋ]), or like the nasal vowels of French.

In contrast to the hiragana syllabary, which is used for those Japanese language words and grammatical inflections which kanji does not cover, the katakana syllabary is primarily used for transcription of foreign language words into Japanese and the writing of loan words (collectively gairaigo). It is also used for emphasis, to represent onomatopoeia, and to write certain Japanese language words, such as technical and scientific terms, and the names of plants, animals, and minerals. Names of Japanese companies are also often written in katakana rather than the other systems.

Katakana are characterized by short, straight strokes and angular corners, and are the simplest of the Japanese scripts.[3] There are two main systems of ordering katakana: the old-fashioned iroha ordering, and the more prevalent gojūon ordering.

Writing system

| a | i | u | e | o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | ア | イ | ウ | エ | オ |

| K | カ | キ | ク | ケ | コ |

| S | サ | シ | ス | セ | ソ |

| T | タ | チ | ツ | テ | ト |

| N | ナ | ニ | ヌ | ネ | ノ |

| H | ハ | ヒ | フ | ヘ | ホ |

| M | マ | ミ | ム | メ | モ |

| Y | ヤ | ユ | ヨ | ||

| R | ラ | リ | ル | レ | ロ |

| W | ワ | ヰ | ヱ | ヲ | |

| Other kana and diacritics | |||||

| ン | ッ | ー | ヽ | ゛ | ゜ |

Script

The complete katakana script consists of 51 characters, not counting functional and diacritic marks:

- 5 singular vowels

- 45 distinct consonant-vowel unions, consisting of nine consonants in combination with each of the five vowels

- 1 singular consonant

These are conceived as a 5×10 grid (gojūon, 五十音, lit. "Fifty Sounds"), as illustrated to the right, with the extra character being the anomalous singular consonant ン (n). Three of the syllabograms (yi, ye and wu) never became widespread in any language and are not present at all in modern Japanese.

These basic characters can be modified in various ways. By adding a dakuten marker ( ゛ ), a voiceless consonant is turned into a voiced consonant: k→g, s→z, t→d, and h→b. Katakana beginning with an h can also add a handakuten marker ( ゜ ) changing the h to a p.

Romanisation of the kana does not always strictly follow the consonant-vowel scheme laid out in the table. For example, チ, nominally ti, is very often romanised as chi in an attempt to better represent the actual sound in Japanese.

Japanese syllabary and orthography

The Japanese katakana syllabary consists of 48 syllabograms (the full complement of 51 less yi, ye and wu, which, as mentioned, never became established). However, two of these 48 are now obsolete, and one is preserved only for a single use:

- wi and we are pronounced as vowels in modern Japanese and are therefore obsolete.

- wo is now used only as a particle, and is normally pronounced the same as vowel オ o. As a particle, it is usually written in hiragana (を) and the katakana form, ヲ, is uncommon.

A small version of the katakana for ya, yu or yo (ャ, ュ, or ョ respectively) may be added to katakana ending in i. This changes the i vowel sound to a glide (palatalization) to a, u or o. Addition of the small y kana is called yōon. For example, キ (ki) plus ャ (small ya) becomes キャ (kya).

A character called a sokuon, which is visually identical to small tsu ッ, indicates that the following consonant is geminated (doubled); this is represented in rōmaji by doubling the consonant that follows the sokuon. For example, compare Japanese サカ saka "hill" with サッカ sakka "author" (these examples are for illustration, but in practice these words would normally be written in kanji). Geminated consonants are common in transliterations of foreign loanwords; for example English "bed" is represented as ベッド (beddo). The sokuon also sometimes appears at the end of utterances, where it denotes a glottal stop. However, it cannot be used to double the na, ni, nu, ne, no syllables' consonants – to double these, the singular n (ン) is added in front of the syllable. The sokuon may also be used to approximate a non-native sound; Bach is written バッハ (Bahha); Mach as マッハ (Mahha).

Small versions of the five vowel kana are sometimes used to represent trailing off sounds (ハァ haa, ネェ nee), but in katakana they are more often used in yōon-like extended digraphs designed to represent phonemes not present in Japanese; examples include チェ (che) in チェンジ chenji ("change"), and ウィ (wi) and ディ (di) in ウィキペディア Wikipedia.

Standard and voiced iteration marks are written in katakana as ヽ and ヾ respectively.

Both katakana and hiragana usually spell native long vowels with the addition of a second vowel kana, but katakana uses a vowel extender mark, called a chōonpu ("long vowel mark"), in foreign loanwords. This is a short line (ー) following the direction of the text, horizontal for yokogaki (horizontal text), and vertical for tategaki (vertical text). For example, メール mēru is the gairaigo for e-mail taken from the English word "mail"; the ー lengthens the e. There are some exceptions, such as ローソク (rōsoku (蝋燭, "candle")) or ケータイ(kētai (携帯, "mobile phone")), where Japanese words written in katakana use the elongation mark, too.

Usage

Japanese

In modern Japanese, katakana is most often used for transcription of words from foreign languages (other than words historically imported from Chinese), called gairaigo.[4] For example, "television" is written terebi (テレビ). Similarly, katakana is usually used for country names, foreign places, and foreign personal names. For example, the United States is usually referred to as アメリカ Amerika, rather than in its ateji kanji spelling of 亜米利加 Amerika.

Katakana are also used for onomatopoeia,[4] words used to represent sounds – for example, pinpon (ピンポン), the "ding-dong" sound of a doorbell.

Technical and scientific terms, such as the names of animal and plant species and minerals, are also commonly written in katakana.[5] Homo sapiens (ホモ・サピエンス, Homo sapiensu), as a species, is written hito (ヒト), rather than its kanji 人.

Katakana are also often, but not always, used for transcription of Japanese company names. For example Suzuki is written スズキ, and Toyota is written トヨタ. Katakana are also used for emphasis, especially on signs, advertisements, and hoardings (i.e., billboards). For example, it is common to see ココ koko ("here"), ゴミ gomi ("trash"), or メガネ megane ("glasses"). Words the writer wishes to emphasize in a sentence are also sometimes written in katakana, mirroring the European usage of italics.[4]

Pre-World War II official documents mix katakana and kanji in the same way that hiragana and kanji are mixed in modern Japanese texts, that is, katakana were used for okurigana and particles such as wa or o.

Katakana were also used for telegrams in Japan before 1988, and for computer systems – before the introduction of multibyte characters – in the 1980s. Most computers in that era used katakana instead of kanji or hiragana for output.

Although words borrowed from ancient Chinese are usually written in kanji, loanwords from modern Chinese dialects which are borrowed directly use katakana rather than the Sino-Japanese on'yomi readings.

| Japanese | Rōmaji | Meaning | Kanji | Romanization | Source language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| マージャン | mājan | mahjong | 麻將 | májiàng | Mandarin |

| ウーロン茶 | ūroncha | Oolong tea | 烏龍茶 | wūlóngchá | |

| チャーハン | chāhan | fried rice | 炒飯 | chǎofàn | |

| チャーシュー | chāshū | barbecued pork | 叉焼 | cha siu | Cantonese |

| シューマイ | shūmai | a form of dim sum | 焼売 | siu maai |

The very common Chinese loanword rāmen, written in katakana as ラーメン in Japanese, is rarely written with its kanji (拉麺).[clarification needed]

There are rare instances where the opposite has occurred, with kanji forms created from words originally written in katakana. An example of this is コーヒー kōhī, ("coffee"), which can be alternatively written as 珈琲. This kanji usage is occasionally employed by coffee manufacturers or coffee shops for novelty.

Katakana are used to indicate the on'yomi (Chinese-derived readings) of a kanji in a kanji dictionary. For instance, the kanji 人 has a Japanese pronunciation, written in hiragana as ひと hito (person), as well as a Chinese derived pronunciation, written in katakana as ジン jin (used to denote groups of people). Katakana are sometimes used instead of hiragana as furigana to give the pronunciation of a word written in Roman characters, or for a foreign word, which is written as kanji for the meaning, but intended to be pronounced as the original.

Katakana are also sometimes used to indicate words being spoken in a foreign or otherwise unusual accent, by foreign characters, robots, etc. For example, in a manga, the speech of a foreign character or a robot may be represented by コンニチワ konnichiwa ("hello") instead of the more typical hiragana こんにちは. Some Japanese personal names are written in katakana. This was more common in the past, hence elderly women often have katakana names.

It is very common to write words with difficult-to-read kanji in katakana. This phenomenon is often seen with medical terminology. For example, in the word 皮膚科 hifuka ("dermatology"), the second kanji, 膚, is considered difficult to read, and thus the word hifuka is commonly written 皮フ科 or ヒフ科, mixing kanji and katakana. Similarly, the difficult-to-read kanji such as 癌 gan ("cancer") are often written in katakana or hiragana.

Katakana is also used for traditional musical notations, as in the Tozan-ryū of shakuhachi, and in sankyoku ensembles with koto, shamisen, and shakuhachi.

Some instructors for Japanese as a foreign language "introduce katakana after the students have learned to read and write sentences in hiragana without difficulty and know the rules."[6] Most students who have learned hiragana "do not have great difficulty in memorizing" katakana as well.[7] Other instructors introduce the katakana first, because these are used with loanwords. This gives students a chance to practice reading and writing kana with meaningful words. This was the approach taken by the influential American linguistics scholar Eleanor Harz Jorden in Japanese: The Written Language (parallel to Japanese: The Spoken Language).[8]

Ainu

Katakana is commonly used to write the Ainu language by Japanese linguists. In Ainu language katakana usage, the consonant that comes at the end of a syllable is represented by a small version of a katakana that corresponds to that final consonant and with an arbitrary vowel. For instance "up" is represented by ウㇷ゚ (ウプ [u followed by small pu]). Ainu also requires three additional sounds, represented by セ゜ ([tse]), ツ゜ ([tu̜]) and ト゜ ([tu̜]). In Unicode, the Katakana Phonetic Extensions block (U+31F0–U+31FF) exists for Ainu language support. These characters are used mainly for the Ainu language only.

Taiwanese

Taiwanese kana (タイ![]() ヲァヌ

ヲァヌ![]() ギイ

ギイ![]() カア

カア![]() ビェン

ビェン![]() ) is a katakana-based writing system once used to write Holo Taiwanese, when Taiwan was under Japanese control. It functioned as a phonetic guide for Chinese characters, much like furigana in Japanese or Zhuyin fuhao in Chinese. There were similar systems for other languages in Taiwan as well, including Hakka and Formosan languages.

) is a katakana-based writing system once used to write Holo Taiwanese, when Taiwan was under Japanese control. It functioned as a phonetic guide for Chinese characters, much like furigana in Japanese or Zhuyin fuhao in Chinese. There were similar systems for other languages in Taiwan as well, including Hakka and Formosan languages.

Unlike Japanese or Ainu, Taiwanese kana are used similarly to the Zhùyīn fúhào characters, with kana serving as initials, vowel medials and consonant finals, marked with tonal marks. A dot below the initial kana represented aspirated consonants, and チ, ツ, サ, セ, ソ, ウ and オ with a superpositional bar represented sounds found only in Taiwanese.

Okinawan

Katakana is used as a phonetic guide for the Okinawan language, unlike the various other systems to represent Okinawan, which use hiragana with extensions. The system was devised by the Okinawa Center of Language Study of the University of the Ryukyus. It uses many extensions and yōon to show the many non-Japanese sounds of Okinawan.

Table of katakana

- For modern digraph additions that are used mainly to transcribe other languages, see Transcription into Japanese.

This is a table of katakana together with their Hepburn romanization and rough IPA transcription for their use in Japanese. Katakana with dakuten or handakuten follow the gojūon kana without them.

Some characters (shi シ and tsu ツ, so ソ and n ン) look very similar in print except for the slant and stroke shape. These differences in slant and shape are more prominent when written with an ink brush.

| Monographs (gojūon) | Digraphs (yōon) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | i | u | e | o | ya | yu | yo | |

| ∅ | ア a [a] |

イ i [i] |

ウ u [ɯ] |

エ e [e][n 1] |

オ o [o] |

|||

| K | カ ka [ka] |

キ ki [ki] |

ク ku [kɯ] |

ケ ke [ke] |

コ ko [ko] |

キャ kya [kʲa] |

キュ kyu [kʲɯ] |

キョ kyo [kʲo] |

| S | サ sa [sa] |

シ shi [ɕi] |

ス su [sɯ] |

セ se [se] |

ソ so [so] |

シャ sha [ɕa] |

シュ shu [ɕɯ] |

ショ sho [ɕo] |

| T | タ ta [ta] |

チ chi [t͡ɕi] |

ツ tsu [t͡sɯ] |

テ te [te] |

ト to [to] |

チャ cha [t͡ɕa] |

チュ chu [t͡ɕɯ] |

チョ cho [t͡ɕo] |

| N | ナ na [na] |

ニ ni [ɲi] |

ヌ nu [nɯ] |

ネ ne [ne] |

ノ no [no] |

ニャ nya [ɲa] |

ニュ nyu [ɲɯ] |

ニョ nyo [ɲo] |

| H | ハ ha [ha] |

ヒ hi [çi] |

フ fu [ɸɯ] |

ヘ he [he] |

ホ ho [ho] |

ヒャ hya [ça] |

ヒュ hyu [çɯ] |

ヒョ hyo [ço] |

| M | マ ma [ma] |

ミ mi [mi] |

ム mu [mɯ] |

メ me [me] |

モ mo [mo] |

ミャ mya [mʲa] |

ミュ myu [mʲɯ] |

ミョ myo [mʲo] |

| Y | ヤ ya [ja] |

[n 2] | ユ yu [jɯ] |

エ ye [je] / [e][n 3] |

ヨ yo [jo] |

|||

| R | ラ ra [ɾa] |

リ ri [ɾi] |

ル ru [ɾɯ] |

レ re [ɾe] |

ロ ro [ɾo] |

リャ rya [ɾʲa] |

リュ ryu [ɾʲɯ] |

リョ ryo [ɾʲo] |

| W | ワ wa [ɰa] |

ヰ wi [ɰi] / [i][n 4] |

[n 2] | ヱ we [ɰe] / [e][n 4] |

ヲ wo [ɰo] / [o][n 4] |

|||

| Monographs with diacritics: gojūon with (han)dakuten | Digraphs with diacritics: yōon with (han)dakuten | |||||||

| a | i | u | e | o | ya | yu | yo | |

| G | ガ ga [ɡa] |

ギ gi [ɡi] |

グ gu [ɡɯ] |

ゲ ge [ɡe] |

ゴ go [ɡo] |

ギャ gya [ɡʲa] |

ギュ gyu [ɡʲɯ] |

ギョ gyo [ɡʲo] |

| Z | ザ za [za] |

ジ ji [(d)ʑi] |

ズ zu [(d)zɯ] |

ゼ ze [ze] |

ゾ zo [zo] |

ジャ ja [(d)ʑa] |

ジュ ju [(d)ʑɯ] |

ジョ jo [(d)ʑo] |

| D | ダ da [da] |

ヂ ji [(d)ʑi][n 5] |

ヅ zu [(d)zɯ][n 5] |

デ de [de] |

ド do [do] |

ヂャ ja [(d)ʑa][n 5] |

ヂュ ju [(d)ʑɯ][n 5] |

ヂョ jo [(d)ʑo][n 5] |

| B | バ ba [ba] |

ビ bi [bi] |

ブ bu [bɯ] |

ベ be [be] |

ボ bo [bo] |

ビャ bya [bʲa] |

ビュ byu [bʲɯ] |

ビョ byo [bʲo] |

| P | パ pa [pa] |

ピ pi [pi] |

プ pu [pɯ] |

ペ pe [pe] |

ポ po [po] |

ピャ pya [pʲa] |

ピュ pyu [pʲɯ] |

ピョ pyo [pʲo] |

| Final nasal monograph | Polysyllabic monographs | |||||||

| n | iu | koto | shite | toki | tomo | nari | ||

| * | ン n [m n ɲ ŋ ɴ ɰ̃] |

iu [jɯː] |

ヿ koto [koto] |

shite [ɕite] |

toki [toki] |

tomo [tomo] |

nari [naɾi] | |

| * | domo [domo] |

|||||||

| Functional graphemes | ||||||||

| sokuonfu | chōonpu | odoriji (monosyllable) | odoriji (polysyllable) | |||||

| * | ッ (indicates a geminate consonant) |

ー (indicates a long vowel) |

ヽ (reduplicates and unvoices syllable) |

〱 (reduplicates and unvoices syllable) | ||||

| * | ヾ (reduplicates and voices syllable) |

〱゙ (reduplicates and voices syllable) | ||||||

| * | ヽ゚ (reduplicates and voices syllable) |

〱゚ (reduplicates and voices syllable) | ||||||

Notes

- ^ Prior to the e/ye merger in the mid-Heian period, a different character (𛀀) was used in position e.

- ^ a b Theoretical combinations yi and wu are unused . Some katakana were invented for them by linguists in the Edo and Meiji periods in order to fill out the table, but they were never actually used in normal writing.

- ^ The combination ye existed prior to the mid-Heian period and was represented in very early katakana, but has been extinct for over a thousand years, having merged with e in the 10th century. The ye katakana (エ) was adopted for e (displacing 𛀀, the character originally used for e); the alternate katakana 𛄡 was invented for ye in the Meiji period for use in representations of Old and Early Classical Japanese so as to avoid confusion with the modern use of エ for e.

- ^ a b c The characters in positions wi and we are obsolete in modern Japanese, and have been replaced by イ (i) and エ (e). The character wo, in practice normally pronounced o, is preserved in only one use: as a particle. This is normally written in hiragana (を), so katakana ヲ sees only limited use. See Gojūon and the articles on each character for details.

- ^ a b c d e The ヂ (di) and ヅ (du) kana (often romanised as ji and zu) are primarily used for etymological spelling , when the unvoiced equivalents チ (ti) and ツ (tu) (usually romanised as chi and tsu) undergo a sound change (rendaku) and become voiced when they occur in the middle of a compound word. In other cases, the identically-pronounced ジ (ji) and ズ (zu) are used instead. ヂ (di) and ヅ (du) can never begin a word, and they are not common in katakana, since the concept of rendaku does not apply to transcribed foreign words, one of the major uses of katakana.

History

Katakana was developed in the early Heian Period (AD 794 to 1185) by Buddhist monks from parts of man'yōgana characters as a form of shorthand.[citation needed] For example, ka カ comes from the left side of ka 加 "increase". The adjacent table shows the origins of each katakana: the red markings of the original Chinese character eventually became each corresponding symbol.[9]

Recent findings by Yoshinori Kobayashi, professor of Japanese at Tokushima Bunri University suggest the possibility that the kana system may have originated in the eighth century on the Korean Peninsula and been introduced to Japan through Buddhist texts.[10] However this hypothesis is questioned by other scholars.[11]

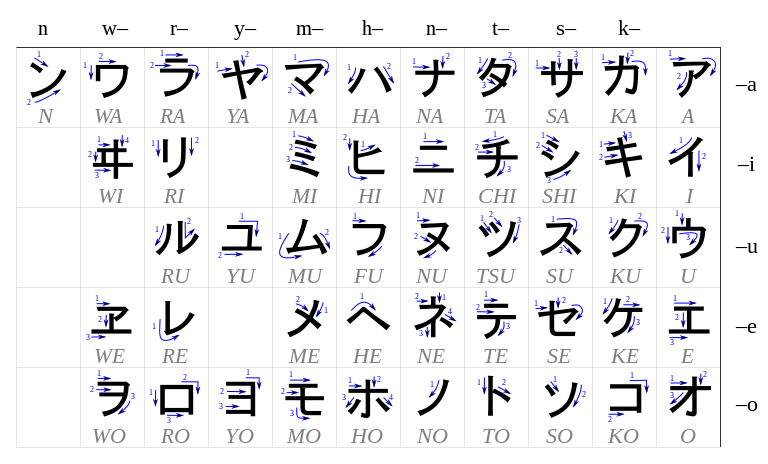

Stroke order

The following table shows the method for writing each katakana character. It is arranged in the traditional way, beginning top right and reading columns down. The numbers and arrows indicate the stroke order and direction respectively.

Computer encoding

In addition to fonts intended for Japanese text and Unicode catch-all fonts (like Arial Unicode MS), many fonts intended for Chinese (such as MS Song) and Korean (such as Batang) also include katakana.

Half-width kana

In addition to the usual full-width (全角, zenkaku) display forms of characters, katakana has a second form, half-width (半角, hankaku) (there are no half-width hiragana or kanji). The half-width forms were originally associated with the JIS X 0201 encoding. Although their display form is not specified in the standard, in practice they were designed to fit into the same rectangle of pixels as Roman letters to enable easy implementation on the computer equipment of the day. This space is narrower than the square space traditionally occupied by Japanese characters, hence the name "half-width". In this scheme, diacritics (dakuten and handakuten) are separate characters. When originally devised, the half-width katakana were represented by a single byte each, as in JIS X 0201, again in line with the capabilities of contemporary computer technology.

In the late 1970s, two-byte character sets such as JIS X 0208 were introduced to support the full range of Japanese characters, including katakana, hiragana and kanji. Their display forms were designed to fit into an approximately square array of pixels, hence the name "full-width". For backwards compatibility, separate support for half-width katakana has continued to be available in modern multi-byte encoding schemes such as Unicode, by having two separate blocks of characters – one displayed as usual (full-width) katakana, the other displayed as half-width katakana.

Although often said to be obsolete, in fact the half-width katakana are still used in many systems and encodings. For example, the titles of mini discs can only be entered in ASCII or half-width katakana, and half-width katakana are commonly used in computerized cash register displays, on shop receipts, and Japanese digital television and DVD subtitles. Several popular Japanese encodings such as EUC-JP, Unicode and Shift-JIS have half-width katakana code as well as full-width. By contrast, ISO-2022-JP has no half-width katakana, and is mainly used over SMTP and NNTP.

Unicode

Katakana was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

The Unicode block for (full-width) katakana is U+30A0 ... U+30FF.

Encoded in this block along with the katakana are the nakaguro word-separation middle dot, the chōon vowel extender, the katakana iteration marks, and a ligature of コト sometimes used in vertical writing.

| Katakana[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+30Ax | ゠ | ァ | ア | ィ | イ | ゥ | ウ | ェ | エ | ォ | オ | カ | ガ | キ | ギ | ク |

| U+30Bx | グ | ケ | ゲ | コ | ゴ | サ | ザ | シ | ジ | ス | ズ | セ | ゼ | ソ | ゾ | タ |

| U+30Cx | ダ | チ | ヂ | ッ | ツ | ヅ | テ | デ | ト | ド | ナ | ニ | ヌ | ネ | ノ | ハ |

| U+30Dx | バ | パ | ヒ | ビ | ピ | フ | ブ | プ | ヘ | ベ | ペ | ホ | ボ | ポ | マ | ミ |

| U+30Ex | ム | メ | モ | ャ | ヤ | ュ | ユ | ョ | ヨ | ラ | リ | ル | レ | ロ | ヮ | ワ |

| U+30Fx | ヰ | ヱ | ヲ | ン | ヴ | ヵ | ヶ | ヷ | ヸ | ヹ | ヺ | ・ | ー | ヽ | ヾ | ヿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

Half-width equivalents to the usual full-width katakana also exist in Unicode. These are encoded within the Halfwidth and Fullwidth forms block (U+FF00–U+FFEF) (which also includes full-width forms of Latin characters, for instance), starting at U+FF65 and ending at U+FF9F (characters U+FF61–U+FF64 are half-width punctuation marks). This block also includes the half-width dakuten and handakuten. The full-width versions of these characters are found in the Hiragana block.

| Segment of Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms Unicode.org chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+FF6x | ⦆ | 。 | 「 | 」 | 、 | ・ | ヲ | ァ | ィ | ゥ | ェ | ォ | ャ | ュ | ョ | ッ |

| U+FF7x | ー | ア | イ | ウ | エ | オ | カ | キ | ク | ケ | コ | サ | シ | ス | セ | ソ |

| U+FF8x | タ | チ | ツ | テ | ト | ナ | ニ | ヌ | ネ | ノ | ハ | ヒ | フ | ヘ | ホ | マ |

| U+FF9x | ミ | ム | メ | モ | ヤ | ユ | ヨ | ラ | リ | ル | レ | ロ | ワ | ン | ゙ | ゚ |

Circled katakana are code points U+32D0 to U+32FE in the Enclosed CJK Letters and Months block (U+3200 - U+32FF). A circled ン (n) is not included.

| Segment of Enclosed CJK Letters and Months Unicode.org chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+32Dx | ㋐ | ㋑ | ㋒ | ㋓ | ㋔ | ㋕ | ㋖ | ㋗ | ㋘ | ㋙ | ㋚ | ㋛ | ㋜ | ㋝ | ㋞ | ㋟ |

| U+32Ex | ㋠ | ㋡ | ㋢ | ㋣ | ㋤ | ㋥ | ㋦ | ㋧ | ㋨ | ㋩ | ㋪ | ㋫ | ㋬ | ㋭ | ㋮ | ㋯ |

| U+32Fx | ㋰ | ㋱ | ㋲ | ㋳ | ㋴ | ㋵ | ㋶ | ㋷ | ㋸ | ㋹ | ㋺ | ㋻ | ㋼ | ㋽ | ㋾ | |

Extensions to Katakana for phonetic transcription of Ainu and other languages were added to the Unicode Standard in March, 2002 with the release of version 3.2.

The Unicode block for Katakana Phonetic Extensions is U+31F0 ... U+31FF:

| Katakana Phonetic Extensions[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+31Fx | ㇰ | ㇱ | ㇲ | ㇳ | ㇴ | ㇵ | ㇶ | ㇷ | ㇸ | ㇹ | ㇺ | ㇻ | ㇼ | ㇽ | ㇾ | ㇿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

Historic and variant forms of Japanese kana characters were added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2010 with the release of version 6.0.

The Unicode block for Kana Supplement is U+1B000 ... U+1B0FF. Grey areas indicate non-assigned code points:

| Kana Supplement[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1B00x | 𛀀 | 𛀁 | 𛀂 | 𛀃 | 𛀄 | 𛀅 | 𛀆 | 𛀇 | 𛀈 | 𛀉 | 𛀊 | 𛀋 | 𛀌 | 𛀍 | 𛀎 | 𛀏 |

| U+1B01x | 𛀐 | 𛀑 | 𛀒 | 𛀓 | 𛀔 | 𛀕 | 𛀖 | 𛀗 | 𛀘 | 𛀙 | 𛀚 | 𛀛 | 𛀜 | 𛀝 | 𛀞 | 𛀟 |

| U+1B02x | 𛀠 | 𛀡 | 𛀢 | 𛀣 | 𛀤 | 𛀥 | 𛀦 | 𛀧 | 𛀨 | 𛀩 | 𛀪 | 𛀫 | 𛀬 | 𛀭 | 𛀮 | 𛀯 |

| U+1B03x | 𛀰 | 𛀱 | 𛀲 | 𛀳 | 𛀴 | 𛀵 | 𛀶 | 𛀷 | 𛀸 | 𛀹 | 𛀺 | 𛀻 | 𛀼 | 𛀽 | 𛀾 | 𛀿 |

| U+1B04x | 𛁀 | 𛁁 | 𛁂 | 𛁃 | 𛁄 | 𛁅 | 𛁆 | 𛁇 | 𛁈 | 𛁉 | 𛁊 | 𛁋 | 𛁌 | 𛁍 | 𛁎 | 𛁏 |

| U+1B05x | 𛁐 | 𛁑 | 𛁒 | 𛁓 | 𛁔 | 𛁕 | 𛁖 | 𛁗 | 𛁘 | 𛁙 | 𛁚 | 𛁛 | 𛁜 | 𛁝 | 𛁞 | 𛁟 |

| U+1B06x | 𛁠 | 𛁡 | 𛁢 | 𛁣 | 𛁤 | 𛁥 | 𛁦 | 𛁧 | 𛁨 | 𛁩 | 𛁪 | 𛁫 | 𛁬 | 𛁭 | 𛁮 | 𛁯 |

| U+1B07x | 𛁰 | 𛁱 | 𛁲 | 𛁳 | 𛁴 | 𛁵 | 𛁶 | 𛁷 | 𛁸 | 𛁹 | 𛁺 | 𛁻 | 𛁼 | 𛁽 | 𛁾 | 𛁿 |

| U+1B08x | 𛂀 | 𛂁 | 𛂂 | 𛂃 | 𛂄 | 𛂅 | 𛂆 | 𛂇 | 𛂈 | 𛂉 | 𛂊 | 𛂋 | 𛂌 | 𛂍 | 𛂎 | 𛂏 |

| U+1B09x | 𛂐 | 𛂑 | 𛂒 | 𛂓 | 𛂔 | 𛂕 | 𛂖 | 𛂗 | 𛂘 | 𛂙 | 𛂚 | 𛂛 | 𛂜 | 𛂝 | 𛂞 | 𛂟 |

| U+1B0Ax | 𛂠 | 𛂡 | 𛂢 | 𛂣 | 𛂤 | 𛂥 | 𛂦 | 𛂧 | 𛂨 | 𛂩 | 𛂪 | 𛂫 | 𛂬 | 𛂭 | 𛂮 | 𛂯 |

| U+1B0Bx | 𛂰 | 𛂱 | 𛂲 | 𛂳 | 𛂴 | 𛂵 | 𛂶 | 𛂷 | 𛂸 | 𛂹 | 𛂺 | 𛂻 | 𛂼 | 𛂽 | 𛂾 | 𛂿 |

| U+1B0Cx | 𛃀 | 𛃁 | 𛃂 | 𛃃 | 𛃄 | 𛃅 | 𛃆 | 𛃇 | 𛃈 | 𛃉 | 𛃊 | 𛃋 | 𛃌 | 𛃍 | 𛃎 | 𛃏 |

| U+1B0Dx | 𛃐 | 𛃑 | 𛃒 | 𛃓 | 𛃔 | 𛃕 | 𛃖 | 𛃗 | 𛃘 | 𛃙 | 𛃚 | 𛃛 | 𛃜 | 𛃝 | 𛃞 | 𛃟 |

| U+1B0Ex | 𛃠 | 𛃡 | 𛃢 | 𛃣 | 𛃤 | 𛃥 | 𛃦 | 𛃧 | 𛃨 | 𛃩 | 𛃪 | 𛃫 | 𛃬 | 𛃭 | 𛃮 | 𛃯 |

| U+1B0Fx | 𛃰 | 𛃱 | 𛃲 | 𛃳 | 𛃴 | 𛃵 | 𛃶 | 𛃷 | 𛃸 | 𛃹 | 𛃺 | 𛃻 | 𛃼 | 𛃽 | 𛃾 | 𛃿 |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

See also

- Japanese phonology

- Historical kana usage

- Rōmaji

- Gugyeol

- Tōdaiji Fujumonkō, oldest example of kanji text with katakana annotations.

References

- ^ Thomas E. McAuley, Language change in East Asia, 2001:90

- ^ Roy Andrew Miller, A Japanese Reader: Graded Lessons in the Modern Language, Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Tokyo, Japan (1966), p. 28, Lesson 7 : Katakana : a—no. "Side by side with hiragana, modern Japanese writing makes use of another complete set of similar symbols called the katakana."

- ^ Miller, p. 28. "The katana symbols, rather simpler, more angular and abrupt in their line than the hiragana..."

- ^ a b c Yookoso! An Invitation to Contemporary Japanese 1st edition McGraw-Hill 1993, page 29 "The Japanese Writing System (2) Katakana"

- ^ "Hiragana, Katakana & Kanji". Japanese Word Characters. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Mutsuko Endo Simon, A Practical Guide for Teachers of Elementary Japanese, Center for Japanese Studies, the University of Michigan (1984) p. 36, 3.3 Katakana

- ^ Simon, p. 36

- ^ Reading Japanese, Lesson 1

- ^ Japanese katakana (Omniglot.com)

- ^ "Katakana system may be Korean, professor says", Japan Times, http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20020404b7.html

- ^ Hirakawa, Minami, ed. (2005). Ancient Japan: The passage the writing system came through (in Japanese). Taishukan Shoten. pp. 185–186. ISBN 4-469-29089-0.